Abstract

Background

The association between periodontitis and atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases (ACVD) has been established in some modestly sized studies (<10 000). Rarely, however, periodontitis has been studied directly; often tooth loss or self-reported periodontitis has been used as a proxy measure for periodontitis. Our aim is to investigate the adjusted association between periodontitis and ACVD among all individuals registered in a large dental school in the Netherlands (Academic Centre for Dentistry Amsterdam (ACTA)).

Methods

Anonymised data were extracted from the electronic health records for all registered patients aged >35 years (period 1998–2013). A participant was recorded as having periodontitis based on diagnostic and treatment codes. Any affirmative answer for cerebrovascular accidents, angina pectoris and/or myocardial infarction labelled a participant as having ACVD. Other risk factors for ACVD, notably age, sex, smoking, diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia and social economic status, were also extracted. Logistic regression analyses were used to evaluate the adjusted associations between periodontitis and ACVD.

Results

60 174 individuals were identified; 4.7% of the periodontitis participants (455/9730) and 1.9% of the non-periodontitis participants (962/50 444) reported ACVD; periodontitis showed a significant association with ACVD (OR 2.52; 95% CI 2.3 to 2.8). After adjustment for the confounders, periodontitis remained independently associated with ACVD (OR 1.59; 95% CI 1.39 to 1.81). With subsequent stratification for age and sex, periodontitis remained independently associated with ACVD.

Conclusions

This cross-sectional analysis of a large cohort in the Netherlands of 60 174 participants shows the independent association of periodontitis with ACVD.

Keywords: Cardiovascular disease, ARTHEROSCLEROSIS, Clinical epidemiology, ORAL HEALTH, BLOOD PRESSURE

Introduction

Periodontitis is a complex, chronic inflammatory disease of the tooth supporting connective tissues and alveolar bone. It is caused by an aberrant host response against oral and dental plaque bacteria.1 2 The host response is further compromised by unfavourable lifestyle factors, such as smoking, and by systemic diseases such as diabetes. If periodontitis is not diagnosed and treated, the chronic periodontal infection may persist over many years. There is progression in the breakdown of tissues, and teeth may become mobile and eventually exfoliate; 8–13% of the population suffers from severe periodontitis.3–5

Periodontitis has been associated with atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases (ACVD), a group of ischaemic diseases that includes fatal and non-fatal coronary heart disease (CHD; angina pectoris (AP), myocardial infarction (MI), CHD death), cerebrovascular accidents (CVA/stroke) and peripheral arterial disease.6 The causal mechanism underlying the association of the two diseases is unclear.7

It has been suggested that periodontitis develops prior to any diagnosis of ACVD. In fact, chronic infections can promote atherosclerosis, which is the main cause of cardiovascular diseases.8–10 Periodontal lesions contain a dysbiotic bacterial composition in the subgingival region, with outgrowth of pathogenic species; so periodontitis could as such promote a chronic infection and bacteria are able to enter into the circulatory system.11–13 Short-lived bacteraemias have been demonstrated, and different studies found periodontal bacteria in atherosclerotic plaques and biopsies.14–16 As a result of these short-lived bacteraemias, four subsequent sequelae have been proposed: (1) a proinflammatory state, as evidenced by increased levels of C reactive protein, other inflammatory markers (interleukine-6, neutrophils), (2) a prothrombotic state, (3) the generation of autoimmunity and (4) dyslipidaemia. Collectively, these conditions may result in endothelial dysfunction.7

In addition, overlapping genetic factors have been identified, which suggest that both diseases may have a similar and perhaps parallel inflammatory pathway.7 17 In addition to the latter suggestion, the epidemiological relationship between periodontitis and ACVD may occur via many shared risk factors that commonly occur in the two diseases: smoking, diabetes mellitus, obesity, major depression, advanced age and male sex.6

Previous epidemiological studies, in various parts of the world, show an increase in the relative risk (RR) for ACVD events or ACVD-related death in participants with periodontitis (estimated RR 1.3; 95% CI 1.0 to 1.5).18 Importantly, a significantly higher incidence of ACVD is seen in participants with a more severe periodontal destruction.19 For CVA and CVA-related death, there are estimated RRs of 1.7 (95% CI 1.2 to 2.4) and 2.1 (95% CI 1.2 to 3.9), respectively, for those with periodontitis.20 Stronger associations are reported for periodontitis and ACVD for those under 65 years of age and in males; the latter National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) III follow-up study showed periodontitis to be associated with ACVD and all-cause mortality in men aged 30–64 years.21 The relative contribution of the risk factors for ACVD may vary as per continent, country and region; for example, there is global variation in common risk factors such as smoking, diet, obesity and diabetes. Epidemiological studies that support the association between periodontitis and ACVD have been performed in many continents, including Asia, North and South America, and Western Europe.19 22

While many studies are based on cross-sectional analyses of cohort data, most studies report about cohorts with fewer than 10 000 participants. In addition, most studies use tooth loss or self-reported periodontitis as a surrogate marker for periodontitis, and report mostly about the separate aspects of ACVD, such as CHD, MI, CVA or death, and rarely these conditions have been combined with overall ACVD as an outcome parameter.

Despite the above research reports, the association between periodontitis and ACVD is not widely known within the medical profession. In the Netherlands, where there is a high level of medical and dental care, epidemiological research on this subject has not been performed yet. In our country, ACVD accounts for 27% of total mortality.23 Although ACVD has declined over the past decades and is no longer the leading cause of death in the Netherlands, currently still about 730 000 persons (4.6% of the total population) are diagnosed with CHD, among whom 120 000 have heart failure and 260 000 have atrial fibrillation. These numbers emphasise the continuous need for dedicated research on the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of ACVD in this country.23

The purpose of the present study is to investigate the association between periodontitis and ACVD within the database of the largest dental school in the Netherlands (Academic Centre for Dentistry Amsterdam (ACTA)). Moreover, using confounding adjusted multivariate and stratified analyses, we take established risk factors for ACVD into account. We hypothesised that the medical records of dental participants with periodontitis more often include cardiovascular diseases.

Methods

Data collection

For data collection, the electronic health record patient database (axiUm, Exan group, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada) of ACTA was used. This database contains individual records of all the dental participants registered at ACTA from 1 January 1998 onwards; we extracted data up to 31 December 2013. To build our database, help from the axiUm management team was required. Anonymised data were prepared and entered into an SPSS file (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, V.21.0, Armonk, New York, USA). We included all participants over 35 years of age in whom ACVD may occur; juvenile and postadolescent forms of periodontitis are excluded.24–26 As this was a retrospective study, no formal consent was required.

All individuals who are enrolled as a dental participant in ACTA are obligated to fill out a medical health questionnaire; this is verified by interview and entered into the electronic health record by the dental professional. This questionnaire contains relevant questions about cardiovascular conditions. For all those included, we used the entries in the medical health questionnaire to determine whether they had had suffered from ACVD. As the purpose of the study is to investigate the association between periodontitis and ACVD, we extracted data about MI, CVA and AP. A patient outcome ACVD was documented when the presence of one or more of these conditions was included in the medical health questionnaire of the patient.

The periodontal-diseased status of study participants was confirmed if at least one of the diagnostic and treatment codes for periodontitis (also corresponding to dental care insurance codes) was found in the electronic health record database.

Periodontitis and ACVD share several covariates which can bias the possible association between ACVD and periodontitis. Therefore, different covariates, notably age, sex, postal code (as a surrogate for social economic status (SES)), smoking, diabetes, hypertension and hypercholesterolaemia were documented on the basis of the electronic health record database. These covariates were also extracted from the electronic health patient database and have been collected through the medical health questionnaires at intake, which contains questions about several aspects of individual background variables, including age and sex (male 0, female 1) and current health status. Yes/no response options are used for questions on smoking, diabetes mellitus, hypertension and hypercholesterolaemia, and these have been coded as bivariate covariates in the database.

Data analysis

Univariate logistic regression analyses were performed to test for an association between ACVD and periodontitis and their shared covariates age, sex, smoking, hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia and SES. Next, multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to investigate the influence of all these covariates on the association between ACVD and periodontitis. No univariate a priori covariate selection was used. The covariates smoking, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia and sex were entered into the multivariate logistic regression analyses as categorical (bivariate) covariates. Age at intake has been used as a continuous variable. The relationship between periodontitis and ACVD has been reported to be stronger in males while it is reported to be absent in individuals above 65 years of age.21 Therefore, subgroup analyses with univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed for the subgroups of individuals above 65 years of age and for males.

To explore whether time and perhaps evolution in healthcare would affect the overall results, the cohort was divided into two equal time periods, specifically participants registered at ACTA between 1 January 1998 and 31 December 2005, and those registered between 1 January 2006 and 31 December 2013. All the analyses described above were also completed for these subgroups.

Statistical analyses and data management were performed using SPSS.

Results

Characteristics of the study population

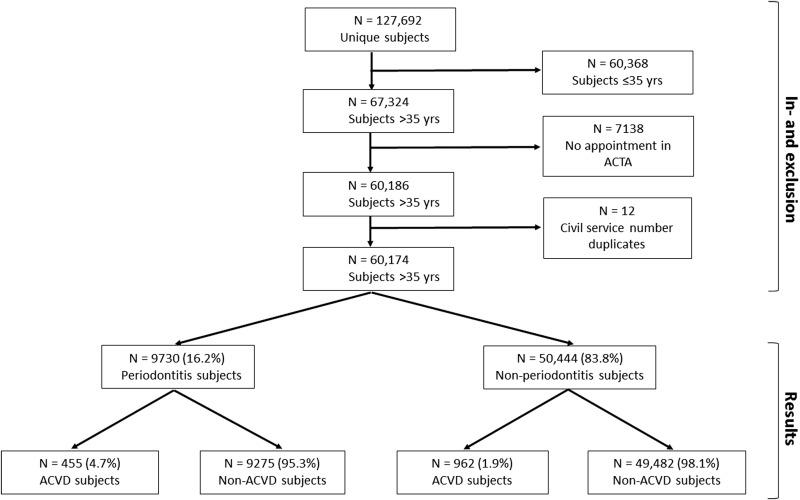

The data were extracted from the ACTA electronic health records (axiUm). Figure 1 is a flow chart showing how the final study sample was obtained. Initially, the file contained 127 692 participants assigned as dental participants at ACTA in this time period. After exclusion of participants up to 36 years of age, 67 324 participants remained. We included participants older than 35 years of age. Out of these participants, 7138 participants were registered as dental participants in ACTA, but never showed up for an intake appointment. After exclusion of these participants, 60 186 participants remained. There were 12 records that, during verification by civil service number, were shown to be duplicates, so these were excluded. The final sample contained 60 174 participants (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart for inclusion in analyses and distribution of dental participants with and without ACVD. ACTA, Academic Centre for Dentistry Amsterdam; ACVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases.

The general characteristics of the study population are presented in table 1. For the total sample, the mean age at the first visit was 51.7 (SD 10.9) years of age. The mean current age on 31 December 2013 was 59.3 (SD 11.3) years. In the total sample, there were 32 378 women (53.8%), 27 591 men (45.9%) and 205 individuals (0.3%) with missing data on sex. Based on postal code, 28 490 participants (47.3%) had a low SES (619 (1.0%) individuals with missing data on postal code). From the total study population, 4568 participants (7.6%) reported smoking, 1707 participants (2.8%) reported suffering from diabetes mellitus, 3327 participants (5.5%) had hypertension and 1575 participants (2.6%) had hypercholesterolaemia. Thus, the total number of participants with missing data (only for sex and postal code; for 2 participants, both parameters were missing) was 822 (1.4%).

Table 1.

Clinical and demographic characteristics of the periodontitis and non-periodontitis participants

| Periodontitis n=9730 (16.2%) |

Non-periodontitis n=50 444 (83.8%) |

Difference (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (intake)* | 49.6 (8.9) | 52.1 (11.2) | 2.5 (2.3 to 2.7) |

| Age (current)* | 58.2 (9.2) | 59.5 (11.7) | 1.3 (1.1 to 1.6) |

| Male sex†‡ | 49.2% | 45.4% | 3.8% (2.8% to 4.9%) |

| Smoking† | 18.8% | 5.4% | 13.3% (12.5% to 14.1%) |

| Diabetes mellitus† | 6.0% | 2.2% | 3.8% (3.3% to 4.3%) |

| Hypertension† | 12.3% | 4.2% | 8.1% (7.4% to 8.7%) |

| Hypercholesterolaemia† | 6.1% | 1.9% | 4.2% (3.7% to 4.7%) |

| Low SES†§ | 51.7% | 47.1% | 4.8% (3.7% to 5.9%) |

*Values are mean in years (SD).

†Values are per cent of participants.

‡Missing data on sex in periodontitis group n=17 (0.2%), non-periodontitis group n=188 (0.4%).

§Missing data on SES in periodontitis group n=68 (0.7%), non-periodontitis group n=551 (1.1%).

SES, social economic status.

Cross-sectional analysis: association of periodontitis with ACVD

The study population consisted of 9730 periodontitis participants (16.2%) and 50 444 non-periodontitis participants (83.8%). In the group of periodontitis participants, 455 (4.7%) were suffering from ACVD, whereas 9275 (95.3%) were not. In the non-periodontitis group, 962 participants (1.9%) were suffering from ACVD whereas 49 482 (98.1%) were not (figure 1).

Table 2 shows the results from the univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses for the association of periodontitis status (yes/no) with ACVD (yes/no) in the total sample (with and without adjustment for covariates), and in subgroups for age (65 years of age or under; over 65 years) and sex. The results show a significant association between periodontitis and ACVD in the total sample (unadjusted OR 2.52; 95% CI 2.25 to 2.82). Subsequently, applying a full model including all covariates (sex, SES, age at intake, smoking, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia), it was shown that there is an independent association between periodontitis and ACVD (adjusted OR 1.59; 95% CI 1.39 to 1.81). The other covariates, except low SES, showed also a significant association with ACVD in the univariate and the multivariate logistic regression analyses (table 2).

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses of risk variables for association with ACVD

| All (n=60 174) | ≤65 years (n=53 075) | Male (n=27 591) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate OR (95% CI) |

Multivariate* OR (95% CI) |

Univariate OR (95% CI) |

Multivariate* OR (95% CI) |

Univariate OR (95% CI) |

Multivariate* OR (95% CI) |

|

| Periodontitis | 2.52 (2.25 to 2.82) | 1.59 (1.39 to 1.81) | 2.80 (2.47 to 3.17) | 1.48 (1.28 to 1.70) | 2.40 (2.08 to 2.78) | 1.61 (1.36 to 1.91) |

| Age at intake (years) | 1.05 (1.04 to 1.05) | 1.05 (1.04 to 1.05) | NA | NA | 1.06 (1.05 to 1.06) | 1.06 (1.05 to 1.06) |

| Male sex | 1.84 (1.65 to 2.05) | 1.76 (1.56 to 1.98) | 1.79 (1.58 to 2.02) | 1.66 (1.46 to 1.90) | NA | NA |

| Smoking | 4.17 (3.68 to 4.73) | 2.96 (2.56 to 3.42) | 4.98 (4.35 to 5.69) | 2.86 (2.46 to 3.32) | 3.37 (2.87 to 3.95) | 2.63 (2.18 to 3.17) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 12.95 (11.33 to 14.80) | 2.57 (2.18 to 3.02) | 14.21 (12.22 to 16.53) | 2.82 (2.34 to 3.40) | 12.16 (10.26 to 14.41) | 2.81 (2.28 to 3.46) |

| Hypertension | 15.64 (13.99 to 17.49) | 5.56 (4.86 to 6.37) | 16.50 (15.52 to 18.75) | 6.50 (5.57 to 7.58) | 15.07 (13.00 to 17.47) | 4.87 (4.08 to 5.81) |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 20.12 (17.70 to 22.89) | 4.61 (3.94 to 5.39) | 21.61 (18.70 to 24.99) | 4.92 (4.10 to 5.88) | 20.33 (17.21 to 24.02) | 5.25 (4.29 to 6.41) |

| Low SES | 1.21 (1.09 to 1.34) | 1.14 (1.02 to 1.28) | 1.26 (1.12 to 1.43) | 1.09 (0.96 to 1.24) | 1.08 (0.94 to 1.24) | 1.07 (0.92 to 1.24) |

For multivariate analyses all variables were included in the model.

*Owing to incomplete data for sex and SES, the number of cases included in multivariate analyses were n=59 352, n=52 335, n=27 210, respectively

ACVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases; NA, not applicable; SES, social economic status.

After stratification for age and sex, a significant univariate association was found between periodontitis and ACVD (adjusted OR ≤65 years 2.80; 95% CI 2.47 to 3.17; male 2.40; 95% CI 2.08 to 2.78). Adjustment for the aforementioned covariates showed periodontitis still to be significantly associated with ACVD (adjusted OR ≤65 years 1.48; 95% CI 1.28 to 1.70; male 1.61; 95% CI 1.36 to 1.91; table 2).

Hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia and smoking showed the strongest associations with ACVD (table 2). Interestingly, it should be noted that the strength of the association with ACVD for periodontitis, age, male sex, smoking and low SES remained fairly stable after covariate adjustment, while the strength of the association for diabetes mellitus, hypertension and hypercholesterolaemia reduced considerably after covariate adjustment (table 2).

We explored the association between periodontitis and MI, CVA or AP. The analyses for these constituent elements of ACVD showed significant associations between periodontitis and MI, CVA or AP without covariate adjustments while, after covariate adjustment, associations for MI and CVA remained statistically significant (adjusted OR 1.60; 95% CI 1.33 to 1.92 and OR 1.55; 95% CI 1.25 to 1.92, respectively). This was not observed for AP in the multivariate model (adjusted OR 1.21; 95% CI 0.97 to 1.49; see online supplementary tables S1–S3).

jech-2015-206745supp_tables.pdf (155.8KB, pdf)

Data analyses stratified for the time periods 1998–2005 and 2006–2013 showed similar results as those of the full study period (data not shown).

Discussion

The association of periodontitis with ACVD has been found in several countries dispersed over all continents. The association has not been investigated in the Netherlands, a country with a relatively high SES and high levels of health and dental care. The current study confirms the independent association between periodontitis and ACVD.

For the purpose of the study, all individuals above 35 years of age in whom ACVD may start were included from a large single-centre cohort in the largest dental school in the Netherlands, while juvenile and postadolescent forms of periodontitis were excluded.24–26 Periodontitis was shown to be significantly associated with ACVD (unadjusted OR 2.52; 95% CI 2.25 to 2.82). After adjustment for known ACVD risk factors (male, SES, age, smoking, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia), periodontitis showed a statistically significant and independent association with ACVD (adjusted OR 1.59; 95% CI 1.39 to 1.81). However, compared with other known risk factors for ACVD, notably hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia and smoking, the association of periodontitis with ACVD is modest. For these latter three traditional risk factors, adjusted ORs in the current study were 5.56, 4.61, 2.96, respectively. Of importance is that the current prevalence of periodontitis (16.2%) is comparable to prevalence estimates of severe periodontitis worldwide and within this dental school, a large over-representation of severe periodontitis is not found.3–5

According to Xu and Lu, the association between periodontitis and ACVD is stronger in the category up to 65 years of age and no association was found in the category above 65 years of age. They also showed a stronger association in males compared with females.21 Therefore, we stratified the cohort by age and sex, and found a stronger association in participants above 65 years of age and a less strong, but still significant, association in participants up to 65 years of age (table 2). Thus, we were unable to corroborate the results reported by Xu and Lu. However, in the subgroup stratified for sex, we found a stronger association between periodontitis and ACVD in men, which corroborates previous findings.21

When interpreting our findings, the following points need consideration. First, an important strength of this study is the successful inclusion of 60 174 participants in our data analyses. The majority of studies on the association between periodontitis and ACVD included fewer than 10 000 participants. The number of missing data was rather low: there were missing data for only 1.4% of the records (n=822). Given the sparse amount of missing data, we decided not to impute because we considered it unlikely that these missing data impacted the validity of the outcome of our complete case multivariate logistic regression analyses (n=59 352).

Second, we used periodontal diagnosis and treatment codes for defining periodontitis, which were clinically validated by dental professionals. The data were derived from the electronic patient database. The dental students and dentists working at ACTA are obligated to enter each specific treatment code when a specific diagnosis or treatment of periodontitis is performed; this is needed (1) for billing or insurance claims, and (2) for study points. These restricted codes are in fact insurance codes and non-modifiable; these are used nationwide as prescribed by the government and insurance companies, and have been in use since 1998. Erroneous coding is highly unlikely, as then the billing to the patient or insurance company will be false. Dental students are also monitored and evaluated by their supervisors to make sure the correct code is used. Most large cohort studies use tooth loss as a surrogate marker for periodontitis or use self-reported periodontitis as exposure data. Hung et al27 showed self-reported tooth loss as a surrogate variable for periodontitis in two separate cohorts of 41 407 male health professionals and 58 975 female nurses to be associated with CHD (RR male: 1.4; RR female: 1.6). Self-reported tooth loss presumably leads to an underestimation of the true tooth loss, and therefore there is an underestimation of the prevalence of periodontitis, and a less strong association between periodontitis and CHD in the latter study. Choe et al28 reported the association between tooth loss as a surrogate variable for periodontitis and stroke in a cohort of 867 256 participants, with higher risk of stroke in those with more tooth loss (HR 1.2). Choe et al did not study other major cardiovascular outcomes such as MI and AP. As both caries and periodontal disease can be the cause of tooth loss, we would expect an overestimation of the prevalence of periodontitis, and therefore an overestimation of the association between periodontitis and ACVD.

Third, defining the presence of ACVD, smoking, diabetes mellitus, hypertension and hypercholesterolaemia was based on the health questionnaire and subsequent interview. This self-reported information may not always be reliable and could introduce bias. However, the medical health questionnaire which was used in the current study has been validated in a multicentre trial within 10 European countries.29 Moreover, the interview also may have contributed to accurate reporting of systemic health-related issues.

Finally, due to the cross-sectional design, the current study does not allow inferences on causal mechanisms or a temporal relationship. However, previous longitudinal studies have shown that a poor periodontal condition was present before any ACVD event occurred. Several cross-sectional epidemiological studies on the relationship between periodontitis and cardiovascular disease have been performed. Elter et al30 reported an increased risk of CHD in individuals with both high periodontal attachment loss and high tooth loss (OR 1.5) and edentulous individuals (OR 1.8). Individuals with a higher extent of sites with attachment loss of at least 3 mm have an increased risk of CVA (OR 1.3).31 Jansson and colleagues performed a study in Sweden with 1393 participants. A significant unadjusted univariate association between participants below 45 years of age with a bone loss exceeding 10% and ACVD-related death has been reported (OR 2.7) which, after stratification for smoking and sex, nearly doubled for smoking males below 45 years of age (OR 4.2).32 The prevalence of smoking (7.6%) in our study was lower than the national average (24%). Smoking was recorded by an affirmative answer on the medical health questionnaire and verified by interview. There was no means to validate ‘non-smoking’ with a breath or blood test, and we could not further address this issue. Obesity has been shown to be an independent risk factor for ACVD.33 The covariates body weight (or body mass index), diet and exercise are common life style variables that are considered risk indicators for periodontitis and ACVD.6 Unfortunately, these were not systematically registered in the electronic health database. Hence, during the analyses we were unable to control for these potential confounding variables. Nevertheless, we have adjusted for seven confounders (sex, SES, age at intake, smoking, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia). Therefore, it was expected that there was not a large additional impact of other potential confounders on our findings. Information about ethnicity was not recorded in the database for privacy reasons.

The study presented here is one of the largest cross-sectional investigations to date investigating the relationship between periodontitis and ACVD. According to the present study, the medical records of dental participants with periodontitis include ACVD more often as compared with dental participants without periodontitis. Therefore, we conclude that periodontitis participants have an increased and independent risk for having ACVD compared with non-periodontitis participants (OR 1.59; 95% CI 1.39 to 1.81).

What is already known on this subject.

Worldwide, cardiovascular diseases are a leading cause of morbidity and mortality. Well-known risk factors include hypercholesterolaemia, diabetes mellitus and smoking. The relationship between cardiovascular diseases and periodontitis has now been suggested for some time. Participants suffering from myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular accidents or atherosclerosis seem to have a higher prevalence of periodontitis. Several mechanisms are proposed for how the association may exist, like presence of short-lived bacteraemias due to periodontitis, increased levels of C reactive protein, establishment of a prothrombotic state, and autoimmune reactions. In addition, in Caucasians, there is evidence for overlapping genetic risk factors. Collectively, these proposed pathways are plausible, and may result in endothelial dysfunction making participants more susceptible to cardiovascular disease events.

What this study adds.

We confirmed the independent association of cardiovascular diseases and periodontitis in an extensive cohort of 60 174 dental participants of a large dental school in the Netherlands, a country with a relatively high social economic status and high levels of health and dental care. After correction for the known risk factors for cardiovascular diseases (age, sex, smoking, diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, social economic status), we observed periodontitis to be highly significantly associated with cardiovascular diseases (OR 1.6, 95% CI 1.4 to 1.8). Hypertension showed the strongest adjusted association with cardiovascular diseases (OR 5.6, 95% CI 4.9 to 6.4). This is the first large-scale study among dental school participants with clear diagnostic and treatment codes specific for periodontitis, showing the association between cardiovascular diseases and periodontitis. Thus, along with the well-known risk factors for cardiovascular diseases, periodontitis should also be considered as a risk.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Charlotte AM Drost and Sophie C Roos for their assistance in piloting the data extraction for this study.

Footnotes

Contributors: NGFMB and BGL conceived and designed the study. NGFMB, GJMGvdH, AJvW and BGL performed the data analyses. NGFMB and BGL wrote the first draft of the paper. NGFMB, BGL and GJMGvdH edited and contributed to discussion.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Pihlstrom BL, Michalowicz BS, Johnson NW. Periodontal diseases. Lancet 2005;366:1809–20. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67728-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laine ML, Crielaard W, Loos BG. Genetic susceptibility to periodontitis. Periodontol 2000 2012;58:37–68. 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2011.00415.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hugoson A, Sjödin B, Norderyd O. Trends over 30 years, 1973–2003, in the prevalence and severity of periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol 2008;35:405–14. 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2008.01225.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eke PI, Dye BA, Wei L, et al. Prevalence of periodontitis in adults in the United States: 2009 and 2010. J Dent Res 2012;91:914–20. 10.1177/0022034512457373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eke PI, Dye BA, Wei L, et al. Update on prevalence of periodontitis in adults in the United States: NHANES 2009 to 2012. J Periodontol 2015;86:611–22. 10.1902/jop.2015.140520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedewald VE, Kornman KS, Beck JD, et al. The American Journal of Cardiology and Journal of Periodontology Editors’ Consensus: periodontitis and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiol 2009;104:59–68. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schenkein HA, Loos BG. Inflammatory mechanisms linking periodontal diseases to cardiovascular diseases. J Clin Periodontol 2013;40(Suppl 14):S51–69. 10.1902/jop.2013.134006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Danesh J, Collins R, Peto R. Chronic infections and coronary heart disease: is there a link? Lancet 1997;350:430–6. 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)03079-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gupta S. Chronic infection in the aetiology of atherosclerosis: focus on Chlamydia pneumoniae. Atherosclerosis 1999;143:1–6. 10.1016/S0021-9150(98)00317-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paoletti R, Gotto AM Jr, Hajjar DP. Inflammation in atherosclerosis and implications for therapy. Circulation 2004;109:III20–6. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000131514.71167.2e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herzberg MC, Weyer MW. Dental plaque, platelets, and cardiovascular diseases. Ann Periodontol 1998;3:151–60. 10.1902/annals.1998.3.1.151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li X, Kolltveit KM, Tronstad L, et al. Systemic diseases caused by oral infection. Clin Microbiol Rev 2000;13:547–58. 10.1128/CMR.13.4.547-558.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loos BG. Systemic markers of inflammation in periodontitis. J Periodontol 2005;76:2106–15. 10.1902/jop.2005.76.11-S.2106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haraszthy VI, Zambon JJ, Trevisan M, et al. Identification of periodontal pathogens in atheromatous plaques. J Periodontol 2000;71:1554–60. 10.1902/jop.2000.71.10.1554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chiu B. Multiple infections in carotid atherosclerotic plaques. Am Heart J 1999;138:S534–6. 10.1016/S0002-8703(99)70294-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ott SJ, El Mokhtari NE, Musfeldt M, et al. Detection of diverse bacterial signatures in atherosclerotic lesions of patients with coronary heart disease. Circulation 2006;113:929–37. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.579979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schaefer AS, Richter GM, Groessner-Schreiber B, et al. Identification of a shared genetic susceptibility locus for coronary heart disease and periodontitis. PLoS Genet 2009;5:e1000378 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Humphrey LL, Fu R, Buckley DI, et al. Periodontal disease and coronary heart disease incidence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med 2008;23:2079–86. 10.1007/s11606-008-0787-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dietrich T, Sharma P, Walter C, et al. The epidemiological evidence behind the association between periodontitis and incident atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. J Clin Periodontol 2013;40(Suppl 14):S70–84. 10.1111/jcpe.12062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu T, Trevisan M, Genco RJ, et al. Examination of the relation between periodontal health status and cardiovascular risk factors: serum total and high density lipoprotein cholesterol, C-reactive protein, and plasma fibrinogen. Am J Epidemiol 2000;151:273–82. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu F, Lu B. Prospective association of periodontal disease with cardiovascular and all-cause mortality: NHANES III follow-up study. Atherosclerosis 2011;218:536–42. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.07.091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lockhart PB, Bolger AF, Papapanou PN, et al. Periodontal disease and atherosclerotic vascular disease: does the evidence support an independent association? A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2012;125:2520–44. 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31825719f3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leening MJ, Siregar S, Vaartjes I, et al. Heart disease in the Netherlands: a quantitative update. Neth Heart J 2014;22:3–10. 10.1007/s12471-013-0504-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tuzcu EM, Kapadia SR, Tutar E, et al. High prevalence of coronary atherosclerosis in asymptomatic teenagers and young adults: evidence from intravascular ultrasound. Circulation 2001;103:2705–10. 10.1161/01.CIR.103.22.2705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McGill HC Jr, McMahan CA, Herderick EE, et al. Origin of atherosclerosis in childhood and adolescence. Am J Clin Nutr 2000;72:1307S–15S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van der Velden U. Purpose and problems of periodontal disease classification. Periodontol 2000 2005;39:13–21. 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2005.00127.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hung HC, Joshipura KJ, Colditz G, et al. The association between tooth loss and coronary heart disease in men and women. J Public Health Dent 2004;64:209–15. 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2004.tb02755.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Choe H, Kim YH, Park JW, et al. Tooth loss, hypertension and risk for stroke in a Korean population. Atherosclerosis 2009;203:550–6. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abraham-Inpijn L, Russell G, Abraham DA, et al. A patient-administered Medical Risk Related History questionnaire (EMRRH) for use in 10 European countries (multicenter trial). Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2008;105:597–605. 10.1016/j.tripleo.2007.09.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Elter JR, Champagne CM, Offenbacher S, et al. Relationship of periodontal disease and tooth loss to prevalence of coronary heart disease. J Periodontol 2004;75:782–90. 10.1902/jop.2004.75.6.782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elter JR, Offenbacher S, Toole JF, et al. Relationship of periodontal disease and edentulism to stroke/TIA. J Dent Res 2003;82:998–1001. 10.1177/154405910308201212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jansson L, Lavstedt S, Frithiof L, et al. Relationship between oral health and mortality in cardiovascular diseases. J Clin Periodontol 2001;28:762–8. 10.1034/j.1600-051X.2001.280807.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Poirier P, Giles TD, Bray GA, et al. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: pathophysiology, evaluation, and effect of weight loss: an update of the 1997 American Heart Association Scientific Statement on Obesity and Heart Disease from the Obesity Committee of the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism. Circulation 2006;113:898–918. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.171016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

jech-2015-206745supp_tables.pdf (155.8KB, pdf)