Abstract

Background

Home is often reported as the preferred place of care for patients at the end-of-life. The support of family caregivers is crucial if this is to be realised. However, little is known about their preferences; a greater understanding would identify how best to support families at the end-of-life, ensuring more patients are cared for in their preferred location.

Objectives

To systematically search and synthesise the qualitative literature exploring the preferences and perspectives of family caregivers towards place of care for their relatives at the end-of-life.

Methods

Ten databases (MEDLINE, PsycINFO, EMBASE, AMED, ASSIA, CINAHL, Social Care Online, Cochrane Database, Scopus, Web of Science) and reference lists of key journals were searched up to January 2014. Included studies were appraised for quality and data thematically synthesised.

Results

Eighteen studies were included; all were of moderate or high quality. Two main themes were identified: (1) Preferences and perspectives: most family caregivers preferred home care, although a range of perspectives were reported. Both positive and negative perspectives of home, hospices and hospitals emerged. At times, family caregivers reported feeling obligated to provide home care. (2) Impact of facilitating home care; both positive and negative effects on family caregivers were reported.

Conclusions

Many family caregivers reported home as the preferred place of care; other places of care were infrequently considered. Healthcare professionals and service providers should be aware of these preferences and provide support where needed to enable family caregivers to successfully care at home, thus improving end-of-life experiences for families as a whole.

Keywords: Palliative care, Family caregiving, Home care, End-of-life preferences, Systematic review

Introduction

Greater understanding of family caregivers’ preferences is needed to identify how best to support families at the end-of-life, to ensure more patients are cared for in their preferred place of care. There are an estimated 500 000 family caregivers1 in the UK, defined as ‘family members, friends and other people who have significant non-professional or unpaid relationships with a patient’2 caring for individuals at the end-of-life.1 Governmental policy3 and third sector guidance1 advise that preferences of patients and family caregivers should be considered when deciding on place of end-of-life care. The preferences of palliative patients surrounding place of care are well-documented; care at home is often preferred.4–6 There is strong evidence to suggest family caregiver support is crucial in facilitating home care,7 but less is known about the preferences and perspectives of these individuals surrounding this topic.2 Improved recognition of family caregiver preferences can be achieved by assessing and collating the preferences of family caregivers through systematic review.

The UK has an aging population, with 10 million individuals currently over 65 years of age.8 In 2012, 71% of all deaths were due to cancer, circulatory and respiratory diseases,9 diseases commonly necessitating a period of palliative care. A large proportion of this end-of-life care is undertaken by family caregivers.2 These individuals form part of a wider group of family caregivers: an estimated 6.5 million individuals in the UK care for people with long-term conditions, or who have conditions associated with aging.10

There is an extensive body of evidence considering patients’ preferences for place of end-of-life care.4–6 One systematic review identified that patients with cancer most commonly preferred to be cared for at home.5 A systematic review focusing on patients with non-malignant disease6 also reported this finding, albeit to a lesser degree. Gomes et al4 systematically reviewed the place of care preferences of patients and family caregivers, again reporting the home the most commonly preferred place of care. However, across the included studies, there was wide variation in the proportions of family caregivers reporting that they preferred home care (25–64%), with little discussion of the reasons behind this.4

Despite the recognition that patients and their families should have a choice about place of end-of-life care,1 3 11 there are concerns that these preferences are not being met.12 Most UK deaths occur in hospital following prolonged illness.3 An analysis of deaths due to cancer between 1993 and 2010 found 48% of patients died in hospital, compared to 24.5% at home and 16.4% in a hospice;13 proportions very different to the expressed preferences of patients.5 6 However, since 2004, the proportion of home deaths has increased and hospital deaths decreased.13 14 Additionally, studies have identified that preferences surrounding place of care and place of death may not be equivalent,15 potentially accounting for some of the observed differences between expressed preferences and place of death. Factors associated with a home death include good social conditions and living with relatives.7 Both formal (healthcare professionals (HCPs)) and informal (family or friends) support networks facilitate caregiving at home.2

A greater understanding of family caregivers’ preferences and perspectives towards place of end-of-life care2 is needed. A qualitative methodological approach is appropriate as preferences and perspectives surrounding palliative care may not be easily quantifiable16 and are most likely to have been studied by qualitative methods. Undertaking a thematic synthesis17 with the identified qualitative data will allow full exploration of these important issues.

The aim of this study was thus to systematically search and synthesise the qualitative literature exploring family caregivers’ preferences and perceptions surrounding place of care of their relatives at the end-of-life. Furthermore, the review sought to explore family caregivers’ perspectives of their relatives’ place of care at the end-of-life.

Methods

Search strategy

Following the development of a review protocol, 10 electronic databases (MEDLINE, PsycINFO, EMBASE, AMED, ASSIA, CINAHL, Social Care Online, The Cochrane Library, Scopus and Web of Science) were selected to reflect various disciplines appropriate to this review (medicine, nursing, allied health professions and social sciences). These were searched from their first publication to January 2014. To identify missed studies, hand-searching key palliative journals’ tables-of-content (Palliative Medicine, BMJ Supportive and Palliative Care, European Journal of Palliative Care and International Journal of Palliative Nursing) was undertaken from first publication to January 2014, and reference lists of articles identified as of interest were reviewed.

A comprehensive search strategy was adopted, attempting to identify all relevant published peer-reviewed articles in this area. Several search term groupings were used, including those considering ‘palliative care’, ‘adult family caregivers’, ‘place of end-of-life care’ and ‘preferences and perceptions’.

The databases were searched using free-text terms and subject headings tailored to specific databases. Limits were applied: English language, considering adults and using qualitative methods (table 1).

Table 1.

Search strategy

| Search line | Term |

|---|---|

| 1 | exp Palliative Care/ |

| 2 | exp Terminal Care/ |

| 3 | exp Terminally Ill/ |

| 4 | exp long-term care/ |

| 5 | exp uncompensated care/ |

| 6 | exp patient-centered care/ |

| 7 | palliat*.mp. |

| 8 | terminal care.mp. |

| 9 | uncompensated care.mp. |

| 10 | nformal care.mp. |

| 11 | end of life care.mp. |

| 12 | end of life care.mp. |

| 13 | disease/ or disease.mp. |

| 14 | iIllness.mp. |

| 15 | cancer*.mp. |

| 16 | malignan*.mp. |

| 17 | non malignant.mp. |

| 18 | advanced.mp. |

| 19 | (advanced adj3 disease).mp. |

| 20 | end stage.mp. |

| 21 | progressive.mp. |

| 22 | terminal.mp. |

| 23 | or/1–12 |

| 24 | or/13–17 |

| 25 | or/18–22 |

| 26 | 24 and 25 |

| 27 | 23 and 26 |

| 28 | caregivers.mp. or exp caregivers/ |

| 29 | informal caregiver.mp. |

| 30 | exp family/ or family.mp. |

| 31 | spouse.mp. or spouses/ |

| 32 | relative*.mp. |

| 33 | carer*.mp. |

| 34 | informal carer*.mp. |

| 35 | home care*.mp. |

| 36 | or/28–35 |

| 37 | exp qualitative research/ |

| 38 | health care surveys/or interviews as topic/or focus groups/or questionnaires/or self-report/ or multicenter studies as topic/or feasibility studies/or pilot projects/ |

| 39 | exp attitude to health/ or exp attitude/ or exp attitude to death/ |

| 40 | attitud*.mp. |

| 41 | exp “Delivery of Health Care”/ |

| 42 | exp Patient Care Planning/ |

| 43 | patient preference.mp. or exp patient preference/ or exp “Patient Acceptance of Health Care”/ |

| 44 | caregiver preference*.mp. |

| 45 | carer preference*.mp. |

| 46 | caregiver perception*.mp. |

| 47 | carer perception*.mp. |

| 48 | perception*.mp. |

| 49 | place of death.mp. |

| 50 | place of care.mp. |

| 51 | location of death.mp. |

| 52 | location of care.mp. |

| 53 | experiences of carer*.mp. |

| 54 | 37 or 38 |

| 55 | or/39–53 |

| 56 | 54 and 55 |

| 57 | 27 and 36 and 56 |

| 58 | limit 57 to (“all adult (19 plus years)” or “young adult (19 to 24 years)” or “adult (19 to 44 years)” or “young adult and adult (19–24 and 19–44)” or “middle age (45 to 64 years)” or “middle aged (45 plus years)” or “all aged (65 and over)” or “aged (80 and over)”) |

| 59 | exp qualitative research/ or qualitative.mp. |

| 60 | 58 and 59 |

The same search terms were used across all databases. Displayed is the search strategy using the OVID search strategy format with limit keywords specific to the OVID databases (MEDLINE, PsycINFO, EMBASE and AMED).

Study selection

Qualitative studies providing insight into family caregivers’ preferences and perspectives of place of end-of-life care were included. Predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria were used.

Inclusion criteria:

Studies with a study population of bereaved or current adult family caregivers of adult patients receiving end-of-life care;

Studies with a focus on family caregivers’ preferences, attitudes and perspectives on place of end-of-life care (these terms must be mentioned in the title and/or aims and objectives and/or main themes of the research article);

Studies from any geographical/national/social settings;

Studies adopting a qualitative design (or mixed-method studies with a qualitative section that met the aforementioned inclusion criteria).

Exclusion criteria:

Studies where the family caregivers are children/young adults, paid carers (such as HCPs or paid in-home carers who provide ‘formal support’) and family caregivers of individuals undergoing curative or maintenance care/treatment;

Studies that focused on discussions surrounding place of care for non-palliative patients, studies that did not express the preferences and views of family caregivers regarding place of care, or studies reporting incidental findings surrounding place of care preferences of family caregivers due to discussion of other palliative care issues;

Articles not in the English language, not peer-reviewed or with a quantitative design.

Two reviewers (CW and JB or SS) independently reviewed all titles and abstracts identified through systematic searching against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Their decisions were combined; a third reviewer (JB or SS) resolved disagreements surrounding inclusion, with resolution by discussion used when necessary. Full text copies of studies considered potentially relevant were accessed and reviewed against the eligibility criteria, determining inclusion. A data extraction sheet was developed to summarise the included study characteristics and their results.

Quality assessment

Quality assessment using a critical appraisal checklist for qualitative studies18 was undertaken, considering the rigour, credibility and relevance of included studies. One reviewer critically appraised all studies; 20% were also assessed by a second reviewer. Studies were then given an overall rating. Studies were considered of high quality when all or almost all of the critical appraisal criteria were fulfilled, with criteria not adequately described thought very unlikely to alter conclusions of the study. Those of moderate quality had most of the criteria fulfilled, with criteria not adequately described thought unlikely to alter the study's conclusions. Low-quality studies were considered to be those with few or no critical appraisal criteria fulfilled, with those criteria not adequately described or fulfilled thought likely to alter conclusions of the study.

Thematic synthesis

A thematic synthesis was undertaken, following Thomas and Harden's three stage process: coding text; development of descriptive themes; analytical theme generation.17

QSR NVivo V.1019 was used for data management and coding; the Portable Document Format of each included article was imported into the programme. Descriptive codes were inductively generated through coding line-by-line the relevant sections of the findings of each study. Further codes were developed through re-reviewing the original data set and recoding where appropriate. The coding framework and initial descriptive themes were then regrouped into distinct analytical thematic hierarchies. Successive versions of the hierarchy were developed and discussed by all authors to improve reliability,20 ensuring the final themes reflected the results of the included studies.

Results

Studies identified

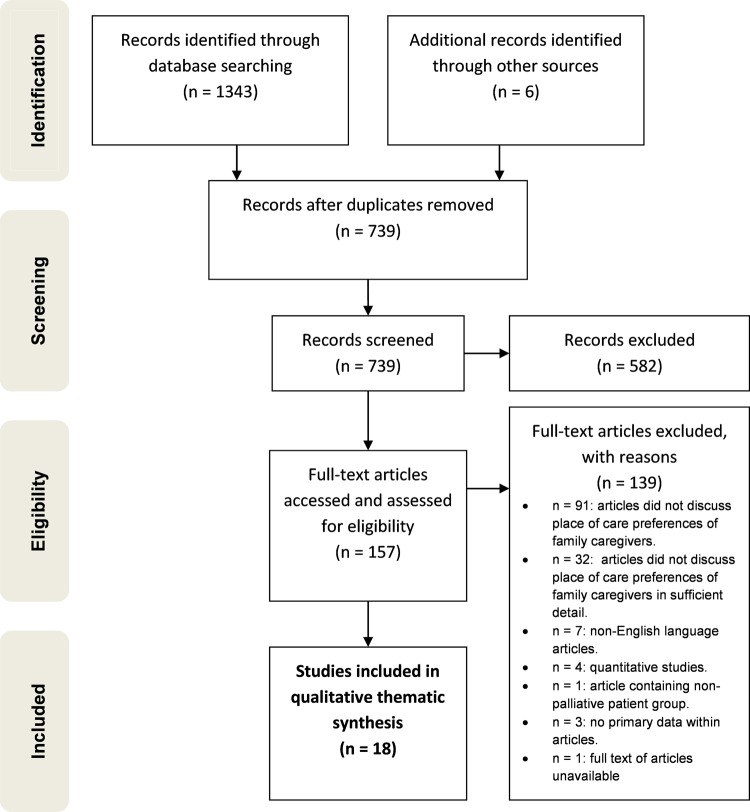

In total 1349 results were identified and 157 full text articles retrieved. Eighteen articles were eligible for inclusion.21–38 The PRISMA39 flow of studies through the search process with reasons for exclusion is displayed in figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram of Study Review and Selection.39

Included studies

A summary of the included studies is presented in supplementary table S1. All included studies adopted a qualitative approach; no mixed-method studies were found to be eligible. In total, 578 family caregivers were involved in the included studies. Participant demographics were not always fully reported, however, participants encompassed a wide range of ages and relationships to the individuals at the end-of-life. Most were closely related to the patient (commonly a spouse or son/daughter) and were female.

The majority of the studies included family caregivers of individuals with cancer (n=11). The search results revealed few studies considering family caregivers of patients with non-malignant disease (n=4), while a minority did not state the disease (n=3). Home was the primary place of care for the majority of studies (n=10). Interviews were the most frequently cited data collection method (n=13); a range of data analysis methods were used. Table 2 presents the main characteristics of the included studies.

Table 2.

Main characteristics of the included studies

| Characteristics | Variables | Number of studies | Study references |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary place of care | Home | 10 | 22 25 27 29 31–33 35 37 38 |

| Range (including home, hospital or hospice) or not explicitly stated | 7 | 21 24 26 28 30 35 36 | |

| Community hospital | 1 | 23 | |

| Bereaved or current family caregivers | Bereaved | 10 | 22 23 25–31 37 |

| Current | 4 | 21 33 35 38 | |

| Both bereaved and current | 4 | 24 32 34 36 | |

| Diseases of the relatives of the participating family caregivers | Advanced cancer | 11 | 21 25–28 30 31 35–38 |

| Motor-neurone disease | 2 | 24 32 | |

| Range of diseases within study | 2 | 23 34 | |

| Diseases not reported by study | 3 | 22 29 33 | |

| Country of origin | Canada | 5 | 25 33–35 37 |

| Australia | 3 | 21 24 28 | |

| UK | 3 | 23 32 36 | |

| Sweden | 3 | 27 29 38 | |

| China (Hong Kong) | 1 | 30 | |

| Denmark | 1 | 31 | |

| Singapore | 1 | 26 | |

| USA | 1 | 22 | |

| Data collection method | Interviews | 13 | 22 23 25 27 28 30 32–38 |

| Focus groups and interviews used in combination | 3 | 21 26 31 | |

| Focus groups | 1 | 24 | |

| Free-text questionnaire | 1 | 29 | |

| Data analysis method | Qualitative analysis | 4 | 21 23 29 31 |

| Thematic analysis | 3 | 24 26 32 | |

| Interpretive, descriptive analysis | 3 | 25 35 37 | |

| Constant comparative analysis | 3 | 30 34 38 | |

| Hermeneutic approach | 2 | 27 33 | |

| Grounded theory | 1 | 36 | |

| Phenomenological approach | 1 | 28 | |

| Combination of ethnography and grounded theory | 1 | 22 |

Quality of included studies

No differences in overall judgement of study quality were found between reviewers. Thirteen studies were found to be of high methodological quality21–25 27 29–34 37 and five of moderate methodological quality.26 28 35 36 38 No studies were found to be of low methodological quality (see online supplementary table S2).

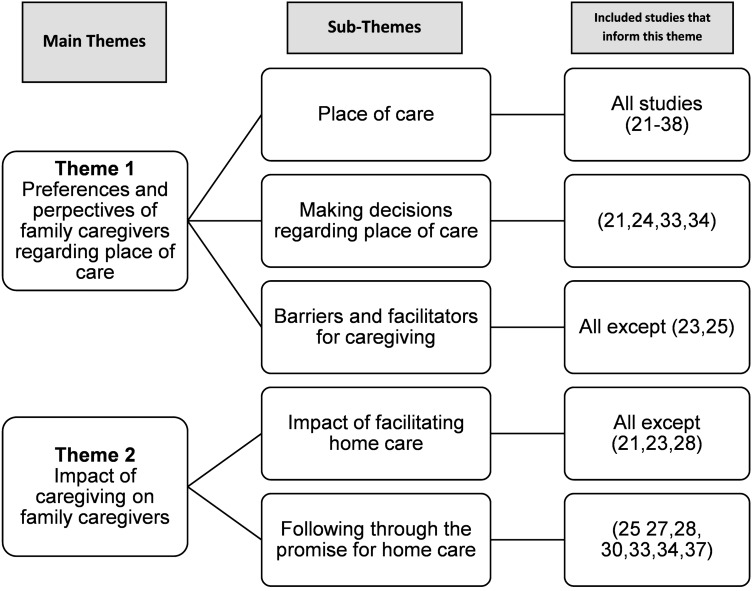

Thematic synthesis

Through descriptive and then analytical theme development, the findings were grouped into two broad themes: (1) preferences and perspectives of family caregivers regarding place of care at the end-of-life; (2) impact of caregiving on family caregivers (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Main themes and sub-themes identified through thematic synthesis.17

Family caregivers’ preferences surrounding place of care, and the perspectives shaping these preferences were often discussed together and are, therefore, considered within the same theme. While this review did not specifically aim to describe the impact that the place of care had on family caregivers, extensive data emerged, informing Theme 2.

Each quotation used is followed by a description of the origin of the quotation. Where details of demographics are omitted, this is due to these details being unreported within the study from which the quotation originates.

Theme 1: preferences and perspectives of family caregivers regarding place of care

Place of care

Sixteen studies reported the home as family caregivers’ preferred place of care.21 22 24–31 33–38 Facilitating home care was recognised as an achievement by family caregivers.25 27 30 33 However, family caregivers in 11 studies recognised and discussed the emotional cost of caregiving,22 24 26 27 29 31–33 35 37 38 with accounts of deteriorating relationships and family conflict:25 27 32 34–36

‘‘When he sees me crying, he just gets mad at me [and says], ‘what the hell's the matter with you? It's not you that's got this problem, it's me’.’’35

(Current female caregiver, wife caring for her husband with cancer at home)

Family caregivers reported how the overwhelming emotional and physical burdens of providing home care often led to admission into formal care settings. However, while the situations of patients and their family caregivers changed, family caregivers often reported how their preferences relating to place of care had not changed; instead they simply felt unable to cope at home any longer.31 33–37

Some family caregivers preferred their relatives to be cared for in a hospice; admission allowed them to connect emotionally with their relatives, without the distraction of providing physical care.24 Family caregivers compared their perceptions of hospital and hospice care:34 36 they were totally different,34 (family caregiver, caring for their father at home) with hospices preferred.34 36 Even if family caregivers preferred home care, hospice services were considered a lifeline,36 (female caregiver; wife caring for her husband with advanced cancer, providing care at home) inspiring the confidence to continue caring at home.

Location preferences could change over time from home to hospital, particularly if distressing symptoms made home care difficult.3 6 Hospital was often described as an unsuitable palliative care environment,34 36 38 often due to its impersonal nature.34 However, one study23 evaluated the palliative care provision of small community hospitals, reporting family caregivers preferred this location due to the quality and personal nature of care provided:

“When I went to [community hospital] they all recognised me and at least would say ‘‘hullo’’ or ‘‘he's such and such today’’…so I was connecting with them…And I know they were all little things, but the little things are the important things.” 23

(Bereaved female family caregiver; wife of a male patient who was cared for within a community hospital)

Two studies discussed respite care and differing opinions emerged.32 38 While some family caregivers preferred not to leave their relatives, others described respite care as valuable;32 38 they enabled care at home to be facilitated for longer:32

“They did take him into (hospice) when I was exhausted. That was wonderful and that took a load off my mind.”32

(Bereaved female former caregiver, caring for an individual with motor-neurone disease)

Lack of knowledge about palliative care service provision was evident in three studies.22 32 38 This related to accessing support services,32 the existence of palliative home support38 and hospice involvement in palliative care.22 One study reported perceptions surrounding hospice improved if family caregivers used their services; participants went from viewing hospices as a place of suffering to a compassionate place of care.36

Decision-making regarding place of care

Family caregivers described helping to decide place of care for their relatives.21 24 33 34 Shared decision-making was preferred;21 improving communication eased caregiving burdens:

“My mother wanted to be at home but I needed her to know that I had limits to what I could do…And the nurse helped us to see that this was kind of a back and forth process and that the decision didn't have to be a final decision. So, in the end, we both felt good about her being at home…We still do”34

(Male family caregiver; son caring for his mother at home)

Preferences for home care were determined by a range of factors. Thirteen studies reported positive perspectives of home care, shaping and determining a preference for this location.22 24–30 33–36 38 Caregiving was described as meaningful22 (bereaved female caregiver; wife who cared for her husband at the end-of-life) and a privilege,27 (bereaved male caregiver; husband caring for his wife at home who had lung cancer), with the home being where optimum care took place:22 24 25

“They probably could not have done any more in the hospital for him than I did.”22

(Bereaved female caregiver)

Family caregivers described facing expectations from their relatives27 30 32 34 38 and HCPs27 to take on the caring role to ensure that home would be the place of care if this was the wish of the patient. One study reported how there was little consideration of the needs of the family caregivers by HCPs.27 Six studies found that participants reported feeling internalised obligations to facilitate care at home; it was a moral duty30 (bereaved male caregiver; husband caring for his wife with advanced cancer, caring at home) or promise,24 27 30 33–35 (female caregiver; wife caring for her husband at home34) made as families look after themselves35 (current family caregiver of an individual with cancer, providing care at home). Feeling obligated to provide care left caregivers with little choice but for home to be the place of care.27 34 35 38

One study, undertaken with current and bereaved caregivers, found bereaved caregivers often reported that they had no choice but to care at home. Current caregivers were more likely to express preferences for home care; ensuring that their relatives did not feel a burden was important.34 Family caregivers reported feeling that their own preferences were unimportant, often ignoring them to facilitate the patient's preferences:22

“If I had my druthers, she would have been in the hospital, but she asked that she not go to the hospital. And like I say you should treat a terminal patient how they want to be treated.”22

(Bereaved female caregiver)

Preferences surrounding other places of care varied with local care provision. If acceptable alternatives to home care were available, participants would consider them a possible care location.34 36 The availability of local palliative care services could thus facilitate or hinder caregiving; further barriers and facilitators are discussed next.

Facilitators and barriers to caregiving

Participants in nine studies described factors that they felt made caregiving at home easier.26–29 31–35 A resilient personality35 or strength within yourself22 (bereaved female caregiver, daughter who had cared for her mother at the end-of-life) eased caregiving. Good family relationships,34 35 knowing that their relative was appreciative of the care received26 35 and feelings of reciprocity35 also helped family caregivers cope.

Participants in 15 studies described their need for support, which was often discussed in relation to home care.21 22 24 27–38 Support, though not always attained or expected,32 37 38 was valued when offered. Support was especially appreciated when making the decision to care,34 discussing the future32 and when caring at home.37 Family caregivers reported how informal support networks were of immense help. Both emotional support and practical help were considered valuable.33 35

Formal support from health services and HCPs was repeatedly described as being of great importance to family caregivers,35 providing security31 to enable care to continue to take place at home. Provision of information was also felt to be important, including how to physically care and the supportive care services available.35 Family caregivers reported that practical relationships with formal support networks, often through visits by HCPs,31 promoted a distribution of responsibility for the physical caring of individuals at the end-of-life,27 enabling patients to be cared for at home for longer. Additionally, a sense that HCPs were involved in supporting the family as a whole was considered beneficial, be it through facilitating communication surrounding end-of-life issues between relatives34 or visiting family caregivers postbereavement.31

Overall, support (both formal and informal) had a substantial impact on family caregivers’ ability to cope with the caregiving role:

“You feel like there is somebody there if you need them...I think that makes it quite a lot [of difference to my coping]…It's a security more than anything.”35

(Current family caregiver, caring for a man with cancer at the end-of-life, providing care at home)

Seven studies explored family caregivers’ perspectives on what made home care more difficult.27 31–35 37 Participants reported difficulties when they were unprepared for, or could no longer cope with, home care.27 31 Family caregivers reported that when they had little choice but to facilitate care at home, with little or no discussion surrounding their own needs and preferences, caregiving was unduly burdensome.34

Difficulties surrounding providing care at home were increased through failures in family caregivers’ informal and formal support networks.32 34 37 Family caregivers reported how feeling failed by close friends who were uncomfortable with the realities of dying increased their caregiving burden,35 as did a lack of support from HCPs.32 37 Interestingly, one study reported heterogeneity in the perspectives of family caregivers on the provision of support.35 While participants reported that formal support eased the caregiving role, one family caregiver described how an over-abundance of support gave the care provided by HCPs an impersonal aspect, increasing the caring burden:

“It was so many names, so many new people coming and going...So on one hand, you're wanting people, [but] on another hand, you just want to be left alone”35

(Current family caregiver of a patient with cancer, providing care at home)

Theme 2: impact of caregiving on family caregivers

Impact of facilitating home care

Participants in the included studies described how caregiving had a positive impact, allowing them to demonstrate love for their relative.22 24 30 33 36 Experiencing the illness trajectory together was beneficial,26 allowing families to feel a greater sense of ‘togetherness’:27

“I spent the last 3 months with him...that to me was fantastic; to be able to spend total time with him, the journey with him”26

(Bereaved family caregiver of a male patient with advanced cancer)

Family caregivers also reported negative consequences of caring for relatives at home. There was little escape from the caregiving role:29 the meaning of ‘home’ changed,29 32 35 becoming an impersonal and medicalised environment.29 Family caregivers described feeling ignored and alone,27 29 32 33 especially when they felt palliative care services overlooked their role in providing care.27 The consequences of this sense of isolation could be devastating:

“Nobody comes to see you and says how are you managing, you just get on with it, and then something, you flip and you've got to realise you can't manage”32

(Bereaved female caregiver caring for an individual with motor-neurone disease)

Following through the promise for home care

Great significance was placed on caring for relatives at home until death by family caregivers.22 25 27 30 34–37 Managing or failing to do so greatly affected family caregivers, both before and after bereavement.

Seven studies described family caregivers’ views on the impact of facilitating a desired home death. Participants in six included studies reported feelings of accomplishment.27 28 30 31 33 37 One study considered how facilitating home care positively impacted on the bereavement experience:25

“The positive being the no regrets, the no guilt. I can't imagine going through a grieving period like I'm going through feeling guilty.”25

(Bereaved family caregiver, who had cared for a patient with advanced cancer at home)

The failure of some family caregivers to facilitate a desired home death had a substantial negative impact on family caregivers,28 31 33 37 and could negatively affect the bereavement experience.37 The language used by participants centred around ideas of failure34 37 and guilt34 (female caregiver; wife caring for her husband with cancer at home):

“I felt like I failed him. I still feel that way. We've been together almost, well, 49 years. And the one thing, I mean he didn't ask much of me, and I couldn't do it [softly crying.]”37

(Bereaved female caregiver; wife caring for her husband with advanced cancer)

Discussion

This systematic review explores the preferences and perspectives of family caregivers surrounding place of care for their relatives at the end-of-life. The majority of included studies considered home as the place of care; many family caregivers within the studies wanted to provide care at home. However, some family caregivers reported caring at home through a sense of obligation: this obligation had various origins, be it through assumptions by patients or by HCPs, or could result from the moral code of the family caregiver themselves. Few studies described the preferences of family caregivers regarding other places of care, or included participants whose relatives had non-malignant disease. Family caregivers supported in their role (by HCPs and informal support) reported a largely positive home care experience.

Home as the place of care was the focus of the included studies. Home was also widely discussed in other systematic reviews considering patient preferences for place of end-of-life care.4 6 The idea that home is the optimum place for end-of-life care has developed over time,5 40 41 and is also observed in non-palliative care situations.42 Government policy now states that patients should be supported to die at home if this is their preference,3 43 as does third sector guidance.1 11 Home death has been described as having the potential to be both the best and worst experience.2 Our systematic review revealed positive and negative perspectives and experiences of caregiving at home; home as the place of care at the end-of-life may not be appropriate for all families,2 despite many family caregivers in the included studies attributing immense importance to facilitating home care.22 25 27 30 34–37 It may be that family caregivers are less likely to prefer home care to patients at the end-of-life.2 44 This was not an explicit finding across the studies included in our review: few family caregivers reported a preference for a care location other than the home. However, a participant within one of the included studies in our review explained how her preferences surrounding place of care differed to those of her relative; while this family caregiver preferred a hospital setting, her relative wished to be cared for within the home.22 Care did take place within the home: the family caregiver reported feeling as having no option but to follow the wishes of her relative at the end-of-life.22 It could be argued that other bereaved caregivers who reported little choice but to care at home34 and participants whose preferences for home care were based in a sense of obligation24 27 30 32–35 38 may not have truly preferred the location of care to be the home.

Issues surrounding preference for place of care have been described as oversimplified.41 Patients’ and family caregivers’ preferences may change over time,5 with potentially different preferences surrounding place of care and place of death.15 While this review found that the location patients received care in varied over time (typically moving from home to hospital), this was rarely to do with a change in preferences of either patient or caregiver, but was often a result of the family caregiver being unable to cope in the caregiving role.31 33–37 However, for some family caregivers in this review, the preferred place of care was different to the preferred place of death; hospice admission at the end-of life was seen as a positive outcome.24

A previous systematic review has reported that patients and their family caregivers have a range of unmet needs at the end-of-life, including those relating to communication, psychosocial issues and a sense of isolation.45 This was recognised in our systematic review; family caregivers described feeling unprepared34 and unsupported,27 29 32 33 often leading to hospital admission,31 33–37 meaning the desired place of death of both patient and caregiver was not achieved. Admissions due to social rather than medical causes have long been recognised as an issue within both palliative care40 and elderly care.46 It is recommended that caregivers should be made aware of the commitment and burdens of caregiving before agreeing to provide end-of-life care,1 and that support services are available for family caregivers:2 this is necessary to avoid these crises and negative effects on patients and caregivers as far as possible. It is thus imperative for HCPs to assess the needs of caregivers caring for patients at the end-of-life and for appropriate support to be provided. In Australia, the completion of the Needs Assessment Tool-Caregiver (NAT-C) and a general practice toolkit was found to reduce pre-existing carer anxiety, and improve the physical well-being of non-anxious caregivers, in a randomised controlled trial.47 Furthermore, in the UK the Carer Support Needs Assessment Tool (CS-NAT) has been developed to assess caregivers’ unmet needs,48 and tested for face, content and criterion validity.49

Patients also recognise the burden of facilitating care; desiring not to be a burden is an oft-cited reason for patients to prefer care in places other than the home.2 4 6 15 50 Our review found that open discussions surrounding place of care and the burden of caregiving were appreciated,34 and allowed these issues surrounding the burden of caregiving to be addressed. Advance Care Planning51 documents are used by HCPs as part of the Gold Standards Framework guidelines developed by the National Health Service End of Life Strategy in England to facilitate these discussions.43 However, caution is needed: HCP-led discussions using these documents can increase family caregivers’ sense of obligation to care for their relative.2 This was found within our review; participants reported how they felt further obligation to care, as HCPs assumed that care would take place at home.27 Family caregivers would be perhaps better served by HCPs making no assumptions, and recognising that different family units have different preferences and needs.

Overall the studies reported a balanced view of caregiving, with many highlighting family caregivers’ preferences for home care and the positive and negative aspects of this choice, which were often in vivid detail.24–27 29–33 35 37 38 This balanced viewpoint from family caregivers makes it unlikely that family caregivers were simply reporting an idealised notion of home as the place of care. Two of the studies reported how family caregivers described originally having an idealised notion of home care, but how this dissipated when the realities of caring became evident.34 37 Interestingly, the only study that reported family caregivers who idealised the notion of home care were those who were unable to care for the dying individual at home at all, or only for short periods.28 It could be inferred that once family caregivers had prolonged experience of the challenges of home care, they were very unlikely to give an idealised account of the home as the place of end-of-life care.

Strengths and limitations

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review exclusively considering qualitative research focusing on family caregivers’ perspectives surrounding place of care for palliative patients. The review methodology was comprehensive, with systematic searching of multiple resources. Rigorous eligibility criteria were applied, ensuring included studies fully considered the perspectives of family caregivers relating to place of care. Synthesis of the findings of 18 studies that varied in situation, population and circumstance allowed identification of themes and concepts17 present across sociocultural structures.

As the findings of this review are based on the researchers’ interpretation of the included studies, there may be some ‘subjective bias’.52 However, the reliability of these findings is enhanced by the iterative emergence of the themes throughout the analysis process, and through discussion between three reviewers.20 The transferability of the review is limited by the nature of the included studies: most consider family caregivers of advanced patients with cancer and discuss preferences surrounding home care; this identified deficit in the current literature can be considered a finding in itself.

Implications for policy and practice

Patients’ and family caregivers’ preferences need to be considered when forming policy and guidelines for practice; it is clear from this review and previous work4–6 that many patients and family caregivers desire end-of-life care to take place in the home. If care is to take place at home, then appropriate support mechanisms for patients and caregivers need to be in place.53 While of immense value to family caregivers, HCPs providing physical help with caregiving is not enough. HCPs also need to facilitate open discussions surrounding the feasibility of caring for a loved one at home, without increasing the sense of obligation that family caregivers report feeling.

As this review has shown that preferences surrounding place of care vary with local provision, enduring equitable provision of support and further options for places of care may allow family caregivers to state preferences for other locations of care. This would allow the preferences and perspectives of patients and their family caregivers to be considered, making it more likely that the end of life trajectory is a more positive experience for both patients and their family caregivers.

Conclusions and future directions

Family caregivers’ preferences for locations for place of care for relatives at the end-of-life, other than the home, need further consideration. Preferences of family caregivers would appear to surround the desire to follow their relative's wishes and thus facilitate care at home. However, other places of care are infrequently considered. As many family caregivers reported their preferences for home to be related to a feeling of obligation, further research would be useful to consider whether these ‘obligated preferences’ are ‘true’ preferences, and if so, how best to support family caregivers through these difficult (and often conflicting) emotions. Additionally, exploration of the needs and preferences of family caregivers whose relatives have non-malignant disease is needed, particularly as it is known that these patients are less likely to receive end-of-life care at home.6 HCPs and other service providers should be made aware of these preferences and the perspectives which shape them, to allow further understanding of the role of the family caregiver and ensure appropriate help and support are provided, thus improving end-of-life experiences for families as a whole. Furthermore, while primary research has identified barriers and facilitators to providing palliative care at home,34 systematically collating and reviewing the literature on this topic would allow palliative care support services to be targeted to more specifically support family caregivers. This could ensure that family caregivers can continue to support their relatives at home, if this is theirs and their relative's preferred place of care.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mala Mann from the Cardiff University Systematic Review Network for her help in developing the search strategy.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow the Marie Curie Palliative Care Research Centre at @MCPCRCCardiff

Contributors: CW was responsible for managing the project, undertook the systematic search, analysed the data and drafted the manuscript. JB and SS were responsible for the overall study conception and study design, analysed the data and drafted the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This study was undertaken as part of lead author's research project for her intercalated BSc in Clinical Epidemiology at Cardiff University. This work was supported by Marie Curie Cancer Care core grant funding to the Marie Curie Palliative Care Research Centre, Cardiff based at Cardiff University School of Medicine (grant reference MCCC-FCO-14-C). Dr Stephanie Sivell's post is supported by Marie Curie Cancer Care core grant funding (grant reference MCCC-FCO-14-C). During the completion of the project, Dr Jessica Baillie was funded by National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) clinical trial (ALICAT ref. 10/145/01).

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Marie Curie Cancer Care. Committed to carers: supporting carers of people at the end of life, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Payne S. EAPC Task force on family carers. White Paper on improving support for family carers in palliative care: part 1. Eur J Palliat Care 2010;17:238–45. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Department of Health. End of Life Care Strategy: promoting high quality care for adults at the end of their life. Department of Health, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gomes B, Calanzani N, Gysels M, et al. Heterogeneity and changes in preferences for dying at home: a systematic review. BMC Palliat Care 2013;12:7 10.1186/1472-684X-12-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Higginson IJ, Sen-Gupta GJ. Place of care in advanced cancer: a qualitative systematic literature review of patient preferences. J Palliat Med 2000;3:287–300. 10.1089/jpm.2000.3.287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murtagh F, Bausewein C, Petkova H, et al. Understanding place of death for patients with non malignant conditions: a systematic literature review. Final report NIHR Service Delivery and Organisation Programme: National Institute for Health Research, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gomes B, Higginson IJ. Factors influencing death at home in terminally ill patients with cancer: systematic review. BMJ 2006;332:515–21. 10.1136/bmj.38740.614954.55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cracknell R. Key Issues for the new parliament: the aging population. House of Commons Library Research, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 9.ONS. Statistical bulletin: deaths registered in England and Wales (Series DR). Series DR, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carers UK. Policy briefing May 2014: facts about carers. London, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Macmillan Cancer Support. Always there? The Impact of the End of Life Care Strategy on 24/7 community nursing in England, 2010.

- 12.Gomes B, Calanzani N, Curiale V, et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of home palliative care services for adults with advanced illness and their caregivers. Cochrane Database Sys Rev 2013;6:Cd007760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao W, Ho YK, Verne J, et al. Changing patterns in place of cancer death in England: a population-based study. PLoS Med 2013;10:e1001410 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gomes B, Calanzani N, Higginson IJ. Reversal of the British trends in place of death: time series analysis 2004–2010. Palliat Med 2012;26:102–7. 10.1177/0269216311432329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Agar M, Currow DC, Shelby-James TM, et al. Preference for place of care and place of death in palliative care: are these different questions? Palliat Med 2008;22:787–95. doi:10.1177/0269216308092287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gysels M, Shipman C, Higginson IJ. Is the qualitative research interview an acceptable medium for research with palliative care patients and carers? BMC Med Ethics 2008;9:7 10.1186/1472-6939-9-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2008;8:45 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. 10 questions to help you make sense of qualitative research 2013. http://media.wix.com/ugd/dded87_951541699e9edc71ce66c9bac4734c69.pdf

- 19.NVivo qualitative data analysis software. 10th edition [program], 2012.

- 20.Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N. Qualitative research in health care. Analysing qualitative data. BMJ 2000;320:114–16. 10.1136/bmj.320.7227.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clayton JM, Butow PN, Arnold RM, et al. Discussing end-of-life issues with terminally ill cancer patients and their carers: a qualitative study. Support Care Cancer 2005;13:589–99. 10.1007/s00520-004-0759-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Enyert G, Burman ME. A qualitative study of self-transcendence in caregivers of terminally ill patients. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 1999;16:455–62. 10.1177/104990919901600207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hawker S, Kerr C, Payne S, et al. End-of-life care in community hospitals: the perceptions of bereaved family members. Palliat Med 2006;20:541–7. 10.1191/0269216306pm1170oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herz H, McKinnon PM, Butow PN. Proof of love and other themes: a qualitative exploration of the experience of caring for people with motor neurone disease. Prog Palliat Care 2006;14:209–14. 10.1179/096992606X146354 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koop PM, Strang VR. The bereavement experience following home-based family caregiving for persons with advanced cancer. Clin Nurs Res 2003;12:127–44. 10.1177/1054773803012002002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee GL, Woo IMH, Goh C. Understanding the concept of a good death among bereaved family caregivers of cancer patients in Singapore. Palliat Support Care 2012;11:37–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Linderholm M, Friedrichsen M. A desire to be seen: family caregivers’ experiences of their caring role in palliative home care. Cancer Nurs 2010;33:28–36. 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181af4f61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McGrath P. End-of-life care for hematological malignancies: the ‘technological imperative’ and palliative care. J Palliat Care 2002;18:39–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Milberg A, Strang P, Carlsson M, et al. Advanced palliative home care: next-of-Kin's perspective. J Palliat Med 2003;6:749–56. 10.1089/109662103322515257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mok E, Chan F, Chan V, et al. Family experience caring for terminally ill patients with cancer in Hong Kong. Cancer Nurs 2003;26:267–75. 10.1097/00002820-200308000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neergaard MA, Olesen F, Jensen AB, et al. Palliative care for cancer patients in a primary health care setting: bereaved relatives’ experience, a qualitative group interview study. BMC Palliat Care 2008;7:1 10.1186/1472-684X-7-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O'Brien MR, Whitehead B, Jack BA, et al. The need for support services for family carers of people with motor neurone disease (MND): views of current and former family caregivers a qualitative study. Disabil Rehabil 2012;34:247–56. 10.3109/09638288.2011.605511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Perreault A, Fothergill-Bourbonnais F, Fiset V. The experience of family members caring for a dying loved one. Int J Palliat Nurs 2004;10:133–43. 10.12968/ijpn.2004.10.3.12469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stajduhar KI, Davies B. Variations in and factors influencing family members’ decisions for palliative home care. Palliat Med 2005;19:21–32. 10.1191/0269216305pm963oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stajduhar KI, Martin WL, Barwich D, et al. Factors influencing family caregivers’ ability to cope with providing end-of-life cancer care at home. Cancer Nurs 2008;31:77–85. 10.1097/01.NCC.0000305686.36637.b5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thomas C, Morris SM, Clark D. Place of death: preferences among cancer patients and their carers. Soc Sci Med 2004;58:2431–44. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Topf L, Robinson CA, Bottorff JL. When a desired home death does not occur: the consequences of broken promises. J Palliat Med 2013;16:875–80. 10.1089/jpm.2012.0541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wennman-Larsen A, Tishelman C. Advanced home care for cancer patients at the end of life: a qualitative study of hopes and expectations of family caregivers. Scand J Caring Sci 2002;16:240–7. 10.1046/j.1471-6712.2002.00091.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:7 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thorpe G. Enabling more dying people to remain at home. BMJ 1993;307:915–18. 10.1136/bmj.307.6909.915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Johnston B. Is effective, person-centred, home-based palliative care truly achievable? Palliat Med 2014;28:373–4. 10.1177/0269216314529858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Department of Health. National service framework: long term conditions. Leeds: Department of Health, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Department of Health. Enabling a gold standard of care for all people nearing the end of life. Department of Health, 2010. http://www.goldstandardsframework.org.uk/home [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grande G, Ewing G. Death at home unlikely if informal carers prefer otherwise: implications for policy. Palliat Med 2008;22:971–2. 10.1177/0269216308098805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ventura AD, Burney S, Brooker J, et al. Home-based palliative care: a systematic literature review of the self-reported unmet needs of patients and carers. Palliat Med 2014;28:391–402. 10.1177/0269216313511141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Williams EI, Fitton F. Factors affecting early unplanned readmission of elderly patients to hospital. BMJ 1988;297:784–7. 10.1136/bmj.297.6651.784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mitchell GK, Girgis A, Jiwa M, et al. Providing general practice needs-based care for carers of people with advanced cancer: a randomised controlled trial. Br J Gen Pract 2013;63:e683–90. 10.3399/bjgp13X673694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ewing G, Grande G; on behalf of the National Association for Hospice at Home. Development of a Carer Support Needs Assessment Tool (CSNAT) for end-of-life care practice at home: a qualitative study. Pall Med 2013;27:244–56. 10.1177/0269216312440607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ewing G, Brundle C, Payne S, et al. The Carer Support Needs Assessment Tool (CSNAT) for use in palliative and end-of-life care at home: a validation study. J Pain Symptom Manage 2013;46:395–405. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McPherson CJ, Wilson KG, Murray MA. Feeling like a burden to others: a systematic review focusing on the end of life. Palliat Med 2007;21:115–28. 10.1177/0269216307076345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.NHS End of Life Care Programme. Advance Care Planning: A Guide for Health and Social Care Staff, 2007.

- 52.Thompson C, McCaughan D, Cullum N, et al. Increasing the visibility of coding decisions in team-based qualitative research in nursing. Int J Nurs Stud 2004;41:15–20. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2003.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hudson PL, Aranda S, Kristjanson LJ. Meeting the supportive needs of family caregivers in palliative care: challenges for health professionals. J Palliat Med 2004;7:19–25. 10.1089/109662104322737214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.