Abstract

A 60-year-old woman was admitted with sepsis, relative bradycardia, CT evidence of numerous small liver abscesses and ‘skin bronzing’ consistent with hereditary haemochromatosis (HH). Yersinia enterocolitica O:9 infection was confirmed by serology specimens taken 10 days apart. Iron overload was detected, and homozygous C282Y gene mutation confirmed HH. Liver biopsy revealed grade IV siderosis with micronodular cirrhosis. Haemochromatosis is a common, inherited disorder leading to iron overload that can produce end-organ damage from excess iron deposition. Haemochromatosis diagnosis allowed aggressive medical management with phlebotomy achieving normalisation of iron stores. Screening for complications of cirrhosis was started that included hepatoma surveillance. Iron overload states are known to increase patient susceptibility to infections caused by lower virulence bacteria lacking sophisticated iron metabolism pathways, for example, Yersinia enterocolitica. Although these serious disseminated infections are rare, they may serve as markers for occult iron overload and should prompt haemochromatosis screening.

Background

Haemochromatosis is a common, inherited disorder leading to iron overload that may be asymptomatic until end-organ damage occurs. Excess iron deposition can produce cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, cardiac, pituitary, joint and gonadal dysfunction. Early diagnosis and implementation of simple management strategies to reduce total body iron can prevent these complications.

Iron overload states increase patient susceptibility to invasive infections caused by bacteria such as Yersinia enterocolitica, which lack sophisticated iron metabolism pathways. Iron-rich host environments can enhance virulence. Although these serious disseminated infections are rare, they may serve as a marker for occult iron overload and should prompt the clinician to screen for haemochromatosis.

Similarly, when sepsis of unclear aetiology is encountered in a patient with iron overload, one should consider microorganisms whose virulence can be enhanced by iron such as Yersinia, Shigella, Vibrio and Listeria.1

Case presentation

A 60-year-old woman was transferred from a regional hospital after 6 days for management of sepsis of unknown aetiology.

Her medical history was significant for anal squamous cell carcinoma managed with abdominal perineal resection and permanent colostomy. She had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and was a current smoker with a 35 pack-year smoking history. She consumed no alcohol. She was married, unemployed and had no other significant personal or family history.

She sought medical attention after a 3-week history of lethargy, anorexia, lower abdominal pain and fevers, preceded by 1 week of increased stoma output and vomiting. There was no significant travel history, animal or sick contact exposure.

On examination, she was febrile (39.3°C), pulse 98 bpm, with blood pressure of 120/80 mm Hg. Relative bradycardia was consistently present during the febrile stage of her illness (see figure 1). The patient had a normal ECG and took no β blockers. She had a ‘bronzed’ complexion (skin described as grey by the admitting team) including non-sun exposed skin, scleral icterus and palmar erythema with no other peripheral stigmata of chronic liver disease observed (see figure 2). Abdominal examination revealed tender hepatomegaly (20 cm) with no evidence of splenomegaly or ascites. The colostomy had normal output.

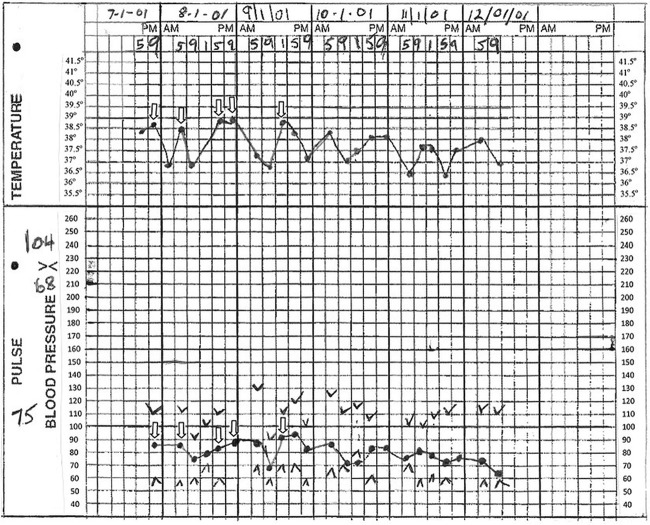

Figure 1.

Vital signs observation chart with temperature, pulse and blood pressure measurements taken prior to patient's transfer to our hospital. Unfilled arrows correspond to temperatures ≥38.5°C with the corresponding pulses also indicated by unfilled arrows. At body temperature ≥38.5°C, pulse rates would be expected to exceed 110 bpm.16

Figure 2.

Patient exhibiting bronzed skin (greyish hue).

Investigations

Full blood count and liver function tests were performed in addition to a septic screen, including urine M/C/S, stool M/C/S and blood cultures and chest X-ray.

White cells were elevated (19.7×109/L) with a neutrophilia (17.9×109/L). Acute phase response was noted with low albumin (23 g /L; reference range (RR) 33–47 g/L) and elevated C reactive protein (216 mg/L; RR <5). She had hyperbilirubinaemia (bilirubin 54 μmol; RR <20 μmol) and a mixed cholestatic and hepatitic derangement (peak alkaline phosphatase (ALP), 756 U/L; RR 30–120 U/L; gamma glutamyl transferase (GGT), 1390 U/L, RR <50 U/L; alanine aminotransferase (ALT), 257 U/L, RR <40 U/L and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 275 U/L, RR <35 U/L). The international normalised ratio was normal, suggesting preservation of hepatic synthetic function.

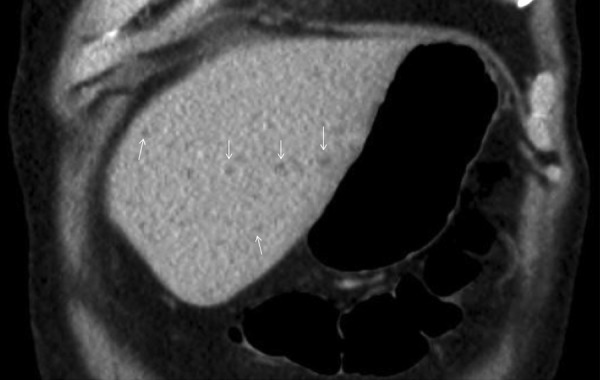

Abdominal ultrasound scan was performed to investigate the deranged liver function tests, which showed a liver with increased echogenicity and irregular contour and patent vessels. The initial CT abdomen with contrast revealed a heterogeneous liver with too numerous to count, small (<5 mm) hypodense lesions consistent with multiple small abscesses (see figure 3).

Figure 3.

CT scan, coronal view, showing multiple small hypodense lesions <5 mm in diameter (indicated by small arrows (↓)) that represent small liver abscesses. These lesions resolved following antibiotic treatment.

Cultures of urine, blood and stool remained negative, but samples had been collected following the administration of antibiotics at the initial presenting hospital.

Paired Yersinia serology performed 10 days apart demonstrated sero-conversion. Yersinia enterocolitica O:9 antibody complement fixation titre became significantly elevated (1:8 on admission and 1:256 on convalescent serology performed 10 days later). Titres >1:128 support a diagnosis of Yersinia infection.2 The paired Y. enterocolitica O:3 and Y. pseudotuberculosis complement fixation titres remained unchanged (titre <1:8). CT scan of the abdomen showed resolution of the multiple small hepatic abscesses 1 month post-treatment. Amoebic serology was negative.

Suspected iron overload from our patient's bronzed complexion was confirmed. Hyperferritinaemia was noted (11 200 μg/L; RR 30–300 μg) with a transferrin saturation >95% (RR 15–45%). Iron studies consistent with iron overload persisted after resolution of the Yersinia hepatic infection. HFE gene studies confirmed hereditary haemochromatosis with C282Y homozygous gene mutation. The remainder of the hepatitis screen was negative.

Liver biopsy was performed 1 month postantibiotic treatment and revealed grade IV siderosis and micronodular cirrhosis.

Differential diagnosis

Sepsis with liver abscesses may arise from infections of the biliary tract and bowel and include bowel flora such as Gram-positive Streptococcus milleri, and Gram-negative organisms such as Klebsiella pneumoniae. Less common pathogens include M. tuberculosis, E. histolytica, Cryptococcus and Echinococcus. Iron overload increases the likelihood of siderophilic organisms such as Yersinia, Listeria, Vibrio species and Salmonella.3

Non-infective liver lesions include simple hepatic cysts and neoplasms, although the clinical picture and appearances of the lesions on ultrasound and CT scans in this case favoured abscess as aetiology. Radiological resolution of the abscesses following antibiotic therapy supported this further.

Treatment

At the regional hospital empiric antibiotic therapy of ampicillin, gentamicin and metronidazole was started for a gastrointestinal source. Owing to ongoing fever, elevated inflammatory markers and increasing neutrophil count, therapy was changed to piperacillin/tazobactam with good response. This empiric treatment for liver abscess would treat Yersinia infection that was subsequently serologically confirmed. Treatment duration was 3 weeks. The patient improved clinically and biochemically. C reactive protein that was 216 mg/L at the start of her illness normalised postantibiotic therapy within 4 weeks. No side effects were encountered during the antibiotic course. The multiple small hepatic abscesses resolved.

Outcome and follow-up

Over 10 days, the patient improved clinically and was discharged. She was educated about haemochromatosis. Outpatient management included phlebotomy targeting a serum ferritin <50 μg/L. She was started on six-monthly hepatoma surveillance and underwent gastroscopy for variceal surveillance. No other end-organ damage was noted on endocrinological testing. Target ferritin levels were achieved and monitored, and hepatoma surveillance was continued locally. Fifteen years later, the patient remains well from a hereditary haemochromatosis (HH) perspective with normal iron stores.

Discussion

Yersinia enterocolitica is a Gram-negative, facultatively anaerobic coccobacillus that can cause acute gastroenteritis in humans with diarrhoea, abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting. Yersinia enterocolitica O:9 is a pathogen of low virulence in the absence of free iron because it lacks yersiniabactin, the iron binding siderophore of its virulent relative, Yersinia pestis, the agent of plague.4 5 However, free iron (in haemochromatosis and iron overdose) can quickly induce an invasive phenotype in the otherwise low virulence Yersinia enterocolitica O:9 to produce systemic infection as occurred in our patient.6–11 Yersinia enterocolitica infection can range from an asymptomatic carrier state to multiorgan small abscesses, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, septic arthritis and osteomyelitis4 to disseminated disease, in which mortality can exceed 50%.12 13 The infection may occur following contact with an infected animal, contaminated food (including pork or unpasteurised milk) or environmental source or, rarely, via contaminated blood products.4 Our patient had a gastrointestinal illness that preceded the CT scan diagnosis of multiple small hepatic abscesses. Diagnosis was made by paired serological tests. Although Brucella infection can produce cross-reactive antibodies with Yersinia, only B. suis is endemic to Australia and acquisition is related to feral pig exposure. Our patient had no such exposure.14

Table 1 summarises similar Yersinia enterocolitica cases. Two-thirds of systemic Yersinioses occur in the setting of iron overload.13 Animal models and in vitro studies have illustrated that iron greatly increases Yersinia invasiveness and virulence.15

Table 1.

Previous case descriptions of Yersinia enterocolitica complicating haemochromatosis

| Reference | Presenting symptom | Diagnosis | Location of abscesses | Haemochromatosis diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22 | 59 years, man Fever and abdominal pain |

Y. enterocolitica 0:3 cultured in blood and hepatic abscesses (obtained at time of autopsy) Serum agglutinin antibody titre 1:4000 |

Liver | Autopsy |

| 23 | 56 years, man Fever, diarrhoea, abdominal pain and weight loss, diabetes mellitus and arthralgia |

Blood agar ascitic fluid culture positive for Y. enterocolitica 0:9 Serum agglutinins 1:2560 Brucella agglutination 1:320 |

Peritonitis | Liver biopsy |

| 24 | 72 years, man Malaise, confusion, vomiting, melena, right-sided chest and abdominal pain |

Y. enterocolitica 0:5 cultured from hepatic abscess at autopsy | Liver | Postmortem HH not confirmed |

| 25 | 56 years, man Febrile illness and hepatomegaly Known diabetes mellitus |

Y. pseudotuberculosis positive blood cultures Y. pseudotuberculosis 1:5120 Y. enterocolitica 0:9 1:1280 Low titres Brucella abortus 1:160 |

Sepsis; ?abscess site | Liver biopsy |

| 10 | 38 years, man Febrile gastrointestinal illness |

Y. enterocolitica 0:3 on blood culture Serum agglutinin titre 1:3200 ‘Gram-negative rods’ in microabscesses |

Liver | Liver biopsy |

| 8 | 65 years, man Decompensated cirrhosis with encephalopathy |

Y. enterocolitica serotype 0:3 on blood, ascites and liver biopsy cultures | Liver | Liver biopsy |

| 11 | Case 1: 44 years, man Fevers, abdominal pain, vomiting and hepatomegaly Case 2: 39 years, man Fevers, diarrhoea and hepatomegaly Case 3: 59 years, woman Fevers, abdominal pain and hepatomegaly Known diabetes mellitus |

Case 1: Y. enterocolitica 0:3 on abscess culture Case 2: Y. enterocolitica 0:3 on abscess culture Case 3: Y. enterocolitica 0:3 on abscess culture obtained at laparotomy; positive blood cultures |

Liver | Case 1: liver biopsy Case 2: liver biopsy (6 months postdischarge) Case 3: liver biopsy (2 years postdischarge) |

| 7 | 43 years, man Fevers, abdominal pain and cutaneous rash |

Y. enterocolitica (?Serotype) serum agglutinin antibody titre 1:5120 Positive culture of ascitic fluid, liver abscess and liver biopsy |

Liver | Liver biopsy |

| 6 | 51 years, man Abdominal pain and fevers |

Y. enterocolitica (?serotype) on culture of liver biopsy | Liver | Liver biopsy C282Y homozygous |

HH, hereditary haemochromatosis.

Our patient also exhibited relative bradycardia. Although a patient with a temperature of 39.3°C would be expected have ≥120 pulse, our patient's pulse was 98. Similar relative bradycardia in the setting of fever was evident prior to transfer to our hospital (see figure 1) before effective antimicrobial treatment, consistent with infection with an intracellular pathogen such as Yersinia.16–18

HH is an inherited disorder leading towards iron overload. Heterozygosity occurs in 10% and homozygosity in 0.5% of Caucasians (one in 250 patients), making it the most common inherited condition of Caucasians. The C282Y mutation accounts for 85% of mutations.19 Phenotypic expression occurs in 70% of C282Y homozygotes, and only 10% develop manifestations of disease.20 H63D and S65C are less frequently encountered genetic mutations and rarely cause iron overload in the absence of coexistent C282Y mutation (compound heterozygotes).19

Survival of patients with uncomplicated HH is similar to the normal population.21 Untreated HH can lead to cirrhosis, endocrinopathies (diabetes mellitus, pituitary dysfunction and gonadal failure), skin pigmentation, as well as cardiomyopathy, arthropathies, porphyria cutanea tarda and osteoporosis. Complicated HH is known to reduce life expectancy.21 Complications of cirrhosis are significant, and HH confers a 100-fold increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma.

Early diagnosis enables monitoring of iron load and initiation of iron reduction to prevent end-organ effects. Venesection is usually started when ferritin is >200 μg/L in premenopausal women and >300 μg/L in men. Postmenopausal women have a target ferritin of 50 μg/L in the absence of anaemia or iron deficiency. Morbidity and mortality can improve with phlebotomy.21

Learning points.

Infection with siderophilic organisms should prompt a search for occult iron overload.

Consider siderophilic organisms in septic patients who have hereditary haemochromatosis (HH) or other iron overloaded states.

Systemic Yersinia enterocolitica infection can produce relative bradycardia (pulse temperature dissociation).

Haemochromatosis is a common condition in the Caucasian population, and simple therapeutic intervention can prevent sequelae of iron overload and its morbidity and mortality.

HH-related cirrhosis has significant increase of complications including hepatoma and requires judicious surveillance.

Footnotes

Contributors: PAT wrote the initial draft of the case and performed the initial literature review and provided overview of haemochromatosis. MLW involved in the patient diagnosis and care and edited and revised the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Weinberg ED. Iron loading and disease surveillance. Emerging Infect Dis 1999;5:346–52. 10.3201/eid0503.990305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bottone EJ, Sheehan DJ. Yersinia enterocolitica: guidelines for serologic diagnosis of human infections. Rev Infect Dis 1983;5:898–906. 10.1093/clinids/5.5.898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chemaly RF, Hall GS, Keys TF et al. Microbiology of liver abscesses and the predictive value of abscess gram stain and associated blood cultures. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2003;46:245–8. 10.1016/S0732-8893(03)00088-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bottone EJ. Yersinia enterocolitica: the charisma continues. Clin Microbiol Rev 1997;10:257–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rakin A, Schneider L, Podladchikova O. Hunger for iron: the alternative siderophore iron scavenging systems in highly virulent Yersinia. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2012;2:151 10.3389/fcimb.2012.00151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bergmann TK, Vinding K, Hey H. Multiple hepatic abscesses due to Yersinia enterocolitica infection secondary to primary haemochromatosis. Scand J Gastroenterol 2001;36:891–5. 10.1080/003655201750313450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collazos J, Guerra E, Fernández A et al. Miliary liver abscesses and skin infection due to Yersinia enterocolitica in a patient with unsuspected hemochromatosis. Clin Infect Dis 1995;21:223–4. 10.1093/clinids/21.1.223-a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leyman P, Baert AL, Marchal G et al. Ultrasound and CT of multifocal liver abscesses caused by Yersinia enterocolitica. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1989;13:913–15. 10.1097/00004728-198909000-00033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mofenson HC, Caraccio TR, Sharieff N. Iron sepsis: Yersinia enterocolitica septicemia possibly caused by an overdose of iron. N Engl J Med 1987;316:1092–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olesen LL, Ejlertsen T, Paulsen SM et al. Liver abscesses due to Yersinia enterocolitica in patients with haemochromatosis. J Intern Med 1989;225:351–4. 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1989.tb00094.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vadillo M, Corbella X, Pac V et al. Multiple liver abscesses due to Yersinia enterocolitica discloses primary hemochromatosis: three cases reports and review. Clin Infect Dis 1994;18:938–41. 10.1093/clinids/18.6.938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cover TL, Aber RC. Yersinia enterocolitica N Engl J Med 1989;321:16–24. 10.1056/NEJM198907063210104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smego RA, Frean J, Koornhof HJ. Yersiniosis I: microbiological and clinicoepidemiological aspects of plague and non-plague Yersinia infections. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 1999;18:1–15. 10.1007/s100960050219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muñoz PM, Marín CM, Monreal D et al. Efficacy of several serological tests and antigens for diagnosis of bovine brucellosis in the presence of false-positive serological results due to Yersinia enterocolitica O:9. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 2005;12:141–51. 10.1128/CDLI.12.1.141-151.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robins-Browne RM, Prpic JK. Effects of iron and desferrioxamine on infections with Yersinia enterocolitica. Infect Immun 1985;47:774–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cunha BA. The diagnostic significance of relative bradycardia in infectious disease. Clin Microbiol Infect 2000;6:633–4. 10.1046/j.1469-0691.2000.0194f.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ostergaard L, Huniche B, Andersen PL. Relative bradycardia in infectious diseases. J Infect 1996;33:185–91. 10.1016/S0163-4453(96)92225-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Altavilla D, Losi E, Foca A et al. Bacterial lipopolysaccharides: comparative analysis of the cardiovascular effects of E. coli, S. sonnei and Y. enterocolitica in anesthetized rats. G Batteriol Virol Immunol 1983;76:20–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pietrangelo A. Hereditary hemochromatosis: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Gastroenterology 2010;139:393–408, e1-2 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Allen KJ, Gurrin LC, Constantine CC et al. Iron-overload-related disease in HFE hereditary hemochromatosis. N Engl J Med 2008;358:221–30. 10.1056/NEJMoa073286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Niederau C, Fischer R, Pürschel A et al. Long-term survival in patients with hereditary hemochromatosis. Gastroenterology 1996;110:1107–19. 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8613000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reinicke V, Korner B. Fulminant septicemia caused by Yersinia enterocolitica. Scand J Infect Dis 1977;9:249–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Capron JP, Capron-Chivrac D, Tossou H et al. Spontaneous Yersinia enterocolitica peritonitis in idiopathic hemochromatosis. Gastroenterology 1984;87:1372–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beeching NJ, Hart HH, Synek BJ et al. A patient with hemosiderosis and multiple liver abscesses due to Yersinia enterocolitica. Pathology 1985;17:530–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abbott M, Galloway A, Cunningham JL. Haemochromatosis presenting with a double Yersinia infection. J Infect 1986;13:143–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]