Abstract

Aims

To examine 12-month outcomes of eyes switching from intravitreal ranibizumab to aflibercept for neovascular age-related macular degeneration (nAMD).

Methods

Database observational study of eyes with nAMD tracked by the Fight Retinal Blindness outcome registry that received ranibizumab for at least 12 months before switching to aflibercept and followed for at least 12 months after the switch. Visual acuity (VA) recorded at 12 months after the switch was analysed using locally weighted scatterplot smoothing curves. Lesion activity was graded according to a prospectively identified definition. Main outcomes were change in VA and treatment intervals 12 months after the treatment switch. Secondary outcomes included change in activity grading, effect of duration of treatment before switching and analysis of eyes that switched back.

Results

A total of 384 eyes switched from ranibizumab to aflibercept after a mean duration of 39.8 months on the original treatment. The mean VA did not change from the time of switching treatment (63.4, SD 15.9 logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution letters) to 12 months later (63.3, SD 16.7). While 10% of eyes gained 10 or more letters 12 months after the switch, 13% lost the same amount. The mean number of injections decreased by around one injection in the 12 months after switching (p<0.001), with a decrease in the proportion of choroidal neovascular membrane lesions that were graded as active. Eyes that had been treated for the longest time (49 or more months) before switching had worse vision at the point of switch but neither change in VA nor treatment interval was different between groups. The small proportion (6.9%) of eyes that switched back again to ranibizumab had already lost a mean of 5.2 letters from the first switch to the switch back and continued to lose vision at a similar rate for at least 6 months.

Conclusions

The mean VA of eyes that switched treatments from ranibizumab to aflibercept was not different 12 months later. There was a modest increase in treatment intervals and a somewhat greater proportion of eyes that were graded as inactive after the switch.

Keywords: Macula, Neovascularisation, Retina, Vision, Field of vision

Introduction

Drugs that inhibit vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) have revolutionised the treatment of neovascular age-related macular degeneration (nAMD), the most common cause of irreversible severe vision loss in the elderly in the developed world.1 The efficacy of a humanised antibody fragment ranibizumab (Lucentis) was shown in pivotal phase III clinical trials.2 3 A randomised multicentre trial found that the efficacy of a humanised murine antibody, bevacizumab (Avastin), on nAMD was broadly similar to that of ranibizumab.4 More recently, a recombinant fusion protein, the decoy receptor aflibercept (Eylea), was shown to improve vision in nAMD, administered every other month after an induction phase. Results were reported to be non-inferior to ranibizumab given monthly.5 While ranibizumab and bevacizumab mainly bind isoforms of VEGF-A, aflibercept binds all isoforms of VEGF-A and VEGF-B as well as placental growth factor, which is also a member of the VEGF family of growth factors.6 The binding affinity of aflibercept to VEGF has been reported to be substantially higher than ranibizumab and bevacizumab.7 It has been suggested that aflibercept persists at therapeutic levels within the eye for 48–83 days after a single injection,8 whereas the intravitreal half-life of ranibizumab was reported to be 7.19 days after a single injection.9

Although many eyes with nAMD do remarkably well with anti-VEGF drugs, some eyes do less well, with recurrent exudation and loss of vision despite regular treatment.10 11 The Comparison of Age-Related Macular Degeneration Treatment Trials reported that 53% of patients treated monthly using ranibizumab and 81% of patients with as-needed treatment using bevacizumab had persistent subretinal fluid 1 year after starting treatment.12

Loss of efficacy of intravitreal therapy for nAMD has been described in patients who had been treated over extended periods.13 Changing treatment from ranibizumab to bevacizumab and vice versa in such patients was reported to result in a better response to treatment.14

The present study aims to examine the 12-month change in visual acuity (VA), lesion activity and treatment interval in a cohort that switched from ranibizumab to aflibercept for nAMD.

Methods

Design

Longitudinal anonymised data from patients treated for nAMD were used in this observational study. Patient outcomes were audited in the Fight Retinal Blindness (FRB) project registry, which was designed to record real-world outcomes in the context of busy retinal practices as described previously.15 The research adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients were informed about the aims and methods of the FRB project and were invited to opt out if they wished. Ethics committee approval and supervision was given by the Human Research Ethics Committees of the respective participating clinics in Australia, New Zealand and Switzerland.

Data collection

VA was recorded at each visit using the logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution (logMAR) letter score. The highest letter score of uncorrected, corrected or pinhole VA was recorded. Variables recorded when treatment was first commenced included type of choroidal neovascular membrane (CNV) lesion seen on angiography, age at presentation of CNV, gender and name of treatment given. Lesions were graded as occult, predominantly classic, minimally classic or other by the treating physician according to angiographic features. VA, lesion activity, name of treatment given and whether a treatment was given were recorded as mandatory fields for each follow-up visit. The decision to treat was made by the treating physician, thus reflecting daily clinical practice.

Patient selection

Data were chosen from the FRB registry for eyes with nAMD that switched from treatment with ranibizumab to aflibercept that had started the original treatment between 2005 and 2013. They had to have been on the original treatment for at least 12 months, and then followed for an additional 12 months after the switch. Occasional injections of bevacizumab were permitted while eyes were being treated with either ranibizumab or aflibercept; this was not considered a treatment switch.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome measures

The two primary outcomes were (i) the mean VA 12 months after switching compared with mean VA at the time of the switch and (ii) the median treatment interval 12 months after switching compared with the median treatment interval at the time of the switch.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes included (i) number of treatments in the 12 months before switching and 12 months after treatment switch, (ii) lesion activity up to 12 months after treatment switch, (iii) local severe adverse events related to injections, (iv) subgroup comparison of the effect of duration of treatment prior to switch on change in VA and treatment interval, (v) subgroup analysis of eyes that switched back to their original treatment including duration of treatments and change in VA. Investigators were asked to grade lesions as active if there was subretinal or intraretinal fluid, or new haemorrhage, which suggested that the lesion was active.

Statistics

All analyses were performed using R, V.3.1.2 (R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: Foundation for Statistical Computing). Descriptive statistics included mean, SD, medians (first and third quartile) or percentages where appropriate. The treatment switch date was taken as the visit at which the change in treatment from ranibizumab to aflibercept occurred.

Locally weighted scatterplot smoothing16 curves were used to calculate VA over time. Comparison of proportions was performed using χ2 tests or Fisher's exact test, while continuous variables were compared before and after the treatment switch using paired t tests or Wilcoxon signed-rank (WSR) tests. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests were performed to compare means between multiple groups.

Treatment intervals were measured as the number of days since the previous injection. This interval was measured for the injection closest to but not exceeding 12 and 6 months before the treatment switch, the injection at the switch point and the injection closest to but not exceeding 6 and 12 months after switch.

Eyes were stratified based on change in VA over time into clinically relevant categories: gain of 15 or more letters, gain of 10−14 letters, gain of 5−9 letters, no change (change between 4 and −4 letters), a loss of 5−9 letters, a loss of 10−14 letters or a loss of 15 or more letters.

Eyes were subgrouped based on the number of months eyes were treated with the original treatment prior to treatment switch: 12–24 months (730 days or less), 25–36 months (between 731 and 1095 days), 37–48 months (between 1096 and 1460 days) and 49 or more months (1461 or more days). All eyes were treated for at least 12 months with the original treatment.

Results

A total of 384 eligible eyes switched from ranibizumab to aflibercept, between 2012 and 2014. They all had at least 12 months follow-up with ranibizumab before the treatment switch to aflibercept and 12 months follow-up after the treatment switch. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of these eyes. Bevacizumab made up 4% of all injections. This was not considered a treatment change because, at least in Australia where the majority (63%) of the cohort came from, the Government provides ranibizumab no more than once every 4 weeks. Many of the eyes that did, or were likely to have, switch treatment were receiving injections more frequently, in which case bevacizumab was given. A majority (59%) of eyes were treated using a treat-and-extent regimen while the remainder was treated using a monthly pro re nata regimen. In all eyes, the proportion of visits where a treatment was given was 78%.

Table 1.

Characteristics of eyes that switched treatments from ranibizumab to aflibercept at the time of this switch, after at least 12 months of ranibizumab

| Switching eyes | |

|---|---|

| Number of eyes | 384 |

| Mean months in treatment prior to switch (SD) | 39.8 (20) |

| Mean VA at switch—logMAR letters (SD) | 63.4 (15.9) |

| Median treatment interval at switch—days (Q1 and Q3) | 42 (31 and 70) |

| Proportion with CNV graded active at switch (%) | 80 |

CNV, choroidal neovascular membrane; logMAR, logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution; Q1, first quartile; Q3, third quartile; VA, visual acuity.

Visual acuity

The mean VA for the 384 eyes that switched treatment at the point of the treatment switch was 63.4 (SD 15.9) letters. Their mean VA 12 months after the treatment switch was unchanged (mean VA 63.3 (SD 16.7) letters, p=0.17, paired t test). VA was unchanged (−4 to +4 letters) in 49% of the eyes at both 6 and 12 months. A 10 or more letter gain was experienced by a small proportion of eyes, 7% after 3 months and 10% after 6 or 12 months. A 10 or more letter loss was experienced by 7% of eyes after 3 months, 10% of eyes after 6 months and 14% of eyes 12 months after treatment switch (table 2).

Table 2.

Stratification of change in visual acuity at 3, 6 and 12 months after switching (%)

| 3 months postswitch (%) | 6 months postswitch (%) | 12 months postswitch (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gain | |||

| ≥15 letters | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| 10–14 letters | 4 | 7 | 6 |

| 5–9 letters | 18 | 18 | 14 |

| No change | 53 | 49 | 49 |

| Loss | |||

| 5–9 letters | 14 | 13 | 13 |

| 10–14 letters | 4 | 6 | 9 |

| ≥15 letters | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Treatment intervals

The median treatment interval at the point of switching was 42 days (Q1=31 and Q3=70), increasing to 56 (Q1=42 and Q3=70) days 12 months later (p<0.001, WSR test) (table 3).

Table 3.

Median (Q1 and Q3) treatment intervals in days before and after switching treatment and mean (SD) number of injections received by 6-month interval for the 384 eyes that switched treatments

| Median treatment interval (Q1 and Q3) (days) | Mean (SD) number of injections | |

|---|---|---|

| 12 months before switch point | 42 (35 and 84) | 3.9 (1.9) |

| 6 months before switch point | 49 (35 and 84) | 3.4 (1.7) |

| At switch | 42 (31 and 70) | |

| 6 months after switch | 56 (42 and 70) | 3.3 (1.2) |

| 12 months after switch | 56 (42 and 80) | 3.2 (1.6) |

Q1, first quartile; Q3, third quartile.

Fewer injections were received in the 12 months after the treatment switch (mean 6.6, SD 2.4) than in the 12 months preceding the treatment switch (mean 7.4, SD 3.0) (p<0.001, paired t test) (table 3). The mean number of injections in the first 3 months after the switch was 2.56±0.73, which is consistent with monthly injections for 3 months after the switch.

Change in CNV activity over time

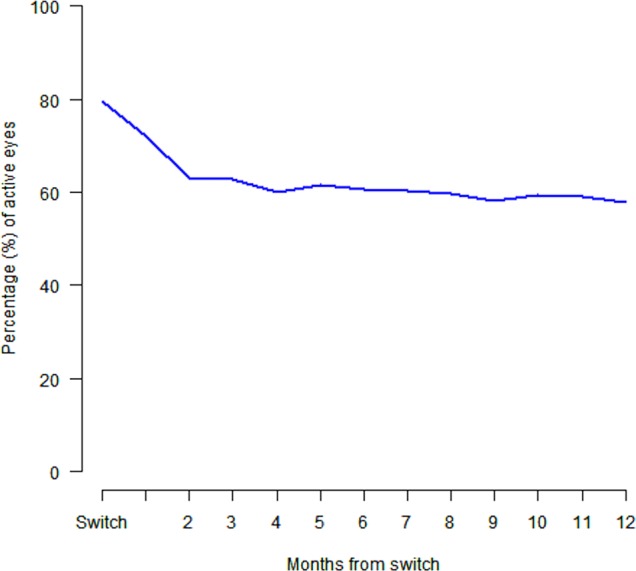

Of the 384 eyes that switched treatment, 306 (80%) eyes had CNV lesions that were graded as active when treatment was switched. This had decreased to 222 (58%) by 12 months after the switch. Figure 1 shows the change in proportion of lesions graded as active from the time of the switch to 12 months postswitch. There was a rapid decline in the proportion of active CNV lesions in the first 2 months after switching (80% to 63%). There was no significant difference in CNV lesion inactivation with respect to lesion type (data not shown).

Figure 1.

The proportion of eyes that were graded as having an active choroidal neovascular membrane throughout the 12 months after switching treatment.

Effect of duration of time treated prior to switch on outcomes

The median time the eyes were treated with ranibizumab before switching to aflibercept was 39.8 months (range=12–103 months). All eyes had been treated for at least 12 months. The 384 eyes were divided into subgroups based on the length of time they had been treated before switching treatments: (i) 12–24 months (105 eyes), (ii) 25–36 months (93 eyes), (iii) 37–48 months (62 eyes) and (iv) 49 or more months (124 eyes). There was a statistically significant difference in mean VA at switch between the four groups (p=0.03, ANOVA). The mean VA at switch for the 124 eyes that had been treated for the longest time (49 or more months) before switching was significantly lower than that of the remaining cohort (60.7 letters (SD=16) vs 65.1 (SD=14.9), p=0.005, t test). The change in VA 12 months after the switch was not different between the groups (p=0.15, ANOVA) (table 4). The treatment interval at the time of switch was similar across all four groups (p=0.42, ANOVA), likewise the treatment interval 12 months after switch (p=0.11, ANOVA) (table 4).

Table 4.

Mean (SD) visual acuity (VA) at the time of switch and the mean (SD) change in VA as well as the median (Q1 and Q3) treatment interval from the time of switch to 12 months after switch for the 384 eyes subgrouped by the length of time treated with ranibizumab prior to treatment switch to aflibercept

| Mean (SD) VA | Median (Q1 and Q3) treatment intervals | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time treated with ranibizumab prior to switch | At switch | Change in VA from switch to 12 months | At switch | 12 months after switch |

| 12–24 months | 65.4 (16.2) | −0.1 (10.8) | 42 (31 and 57) | 56 (41 and 93) |

| 25–36 months | 64.4 (14.7) | −0.4 (7.9) | 42 (28 and 84) | 50 (39 and 72) |

| 37–48 months | 65.6 (13.3) | −3.5 (9.6) | 42 (35 and 85) | 56 (42 and 84) |

| 49 months or more | 60.7 (16.1) | −0.1 (8.8) | 42 (32 and 68) | 56 (42 and 74) |

| p=0.03 | p=0.15 | p=0.42 | p=0.11 | |

Q1, first quartile; Q3, third quartile.

Eyes switching back to original treatment

Twenty-six (6.8%) of the 384 eyes that switched from ranibizumab to aflibercept subsequently switched back to ranibizumab. For these 26 eyes the mean VA at the initial switch to aflibercept was 69.7 (SD 16.2) letters. This initial switch occurred after eyes had been treated with ranibizumab for a mean of 39.8 (SD 16.3) months. Eyes remained on aflibercept for a mean of 15.1 (SD 7.3) months, receiving a mean of 10.4 (SD 4.2) injections. When treatment was switched back to ranibizumab, the mean VA was 64.5 (SD 19.0) letters, representing a mean VA loss of 5.2 letters (SD 9.6, p=0.01, paired t test) between the change to aflibercept and the change back to ranibizumab. There was a significant increase in treatment intervals when eyes returned to ranibizumab treatment (p=0.001, WSR). The last aflibercept treatment was received at a median treatment interval of 35 days (Q1=28 and Q3=48 days), and 6 months after switching back to ranibizumab the median treatment interval was 42 days (Q1=30 and Q3=54 days). A total of 18 (70%) of CNV lesions were graded as active at both the first and the second switch. Although some (35% by 3 months and 42% by 6 months) eyes regained vision to the level it had been before the initial switch to aflibercept after returning to ranibizumab, overall the mean VA of this group continued to decrease. The mean VA at 3 months after treatment returned to ranibizumab was 63.2 (SD=21.0), a further 1.3 letter loss and at 6 months after treatment returned to ranibizumab the mean VA was 62.8 (SD=21.4), a loss of 1.7 letters from the return to ranibizumab.

Adverse events

A small list of significant adverse events was tracked by the FRB nAMD audit. The frequency of these events was observed in the 12 months before and after the treatment switch (table 5).

Table 5.

The risk per injection for adverse events reported in the 12 months before and after treatment switch in the 384 eyes that switched treatments

| Adverse event | 12 months leading up to switch (total 2781 injections) (%) | 12 months postswitch (total 2885 injections*) (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Haemorrhage reducing BCVA by >15 letters | 0.11 | 0.03 |

| Infectious endophthalmitis | 0.00 | 0.03 |

| Non-infectious endophthalmitis | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Intraocular surgery | 0.65 | 0.28 |

| Retinal detachment | 0.00 | 0.03 |

| RPE tear | 0.11 | 0.03 |

*The injection received at time of switch is included in this injection count.

BCVA, best-corrected visual acuity; RPE, retinal pigment epithelium.

Discussion

We found in a large cohort of eyes that switched from ranibizumab to aflibercept that mean VA remained unchanged 12 months after switching. We found that mean VA remained unchanged 12 months after switching. A 10 or more letter gain was found in 10% of eyes, while 13% of eyes lost 10 or more letters. The mean number of injections decreased by around one injection per year in the 12 months after switching, with a rapid decrease in the proportion of CNV lesions that were graded as active within the first 2 months after switching.

There are a few reports on the benefit of switching from ranibizumab to aflibercept in persistently active or ‘recalcitrant’ nAMD.17–23 Most described anatomical improvement but limited improvement in vision.20 22 23 Given the longer calculated half-life in the vitreous cavity and higher binding affinity of aflibercept compared with ranibizumab, many hoped to improve vision or at least increase treatment intervals in patients on long-term treatment with a switch. We did not find an improvement in mean VA 12 months after switching but we did find a modest increase in treatment intervals by about one injection in the 12 months after switching.

Retention of vision in eyes switching treatments in our study was somewhat better than that recently reported,17 where 44% of eyes lost ≥5 logMAR letters by 1 year after the switch. We found that only 23% of switched eyes lost ≥5 logMAR letters, which may be explained by a selection difference between the two studies. Arcinue et al17 included eyes with shorter follow-up and may thus have included eyes with more aggressive lesions, whereas eyes with aggressive lesions with poor outcomes that discontinued treatment early would not have been included in our study.

While we did not find a significant improvement in mean VA, a small proportion (10%) did gain 10 or more letters, but this was offset by a slightly greater proportion of 13% that lost 10 or more letters by 12 months after switching treatment. Thus, we found no functional benefit 12 months after switching from ranibizumab to aflibercept but we cannot exclude the possibility of a benefit with longer term follow-up.

Evaluating the actual effect of change of treatment from ranibizumab to aflibercept can be challenging since several factors have to be taken into account. First, most series have included persistently active cases that needed repetitive anti-VEGF injections over extended periods. Changes, such as scar formation or development of geographic atrophy, may have occurred during this time that would limit improvement in VA, despite a good anatomical response. Recent analyses of eyes on long-term treatment with ranibizumab showed that, despite continuous treatment after an initial gain and plateau, mean VA tends to decline over time.19 21

Both the treatment intervals increased and the proportion of eyes graded as active decreased in the 12 months after switching to aflibercept. The median treatment interval increased from 42 days at the point of switch to 56 days 12 months later, although the mean number of treatments had already dropped from 12 months to 6 months prior to the switch, so the further decrease after switching may have happened even if the eyes had not switched treatment. It is possible that practitioners extended treatment intervals after the switch as the next step in their management approach. On the other hand, the rapid reduction by around 20% of the proportion of eyes that were graded as active over the 2 months after the switch shown in figure 1 suggests that this effect may be related to the switch. Increased treatment intervals after switching treatment from ranibizumab to aflibercept has been reported by others.17 18

It may be argued that variation in treatment regimens affects anatomical and/or functional responses and hence treatment intervals. Given that treatment regimen were either treat-and-extent or monthly pro re nata and did not change after switching, an extension of treatment intervals is likely to reflect actual change in anatomy or lesion activity, that is, an actual effect of the switch.

We also analysed whether duration of treatment with ranibizumab before switching affected outcomes, since structural damage may occur in eyes with advanced AMD over time. We found that the mean VA at the time of switch of the eyes that had been treated for the longest time (49 or more months) before switching was significantly lower than that of the remaining cohort. The subsequent response, however, of this group in terms of change in vision and treatment intervals was similar to the other groups, indicating that whatever benefit there may be of switching treatments is not related to duration of the previous treatment.

A small proportion (6.8%) of eyes that switched from ranibizumab to aflibercept subsequently switched back to ranibizumab after a mean of 15 months and 10 injections. VA in these eyes was quite good (70 letters=20/40) at the initial switch and had dropped around one line by the switch back. A minority of these eyes recovered vision to the level it was at prior to the first switch but the mean VA of this group continued to decline, suggesting that switching back to the original treatment does not have any obvious benefit. There was a significant increase in treatment interval in the 6 months after treatment was returned to ranibizumab of 1 week.

The effects of switching to another drug are difficult to establish without a control group, since some effects that occur over time might have occurred even if the eyes had not switched treatment. We used propensity analysis24 25 in an attempt to identify a matched control group of eyes from a cohort that had been treated continuously with ranibizumab before aflibercept became available, which would have likely switched treatment if aflibercept had been available; however, it was not possible to match the criteria we specified (VA, activity status, treatment interval and duration of treatment before the switch) so we abandoned this analysis. We did not consider it valid to match with contemporaneous controls that did not switch.

Despite the retrospective nature and lack of a control group, this study suggests, along with most other reports on the subject, that there is only a relatively modest benefit of switching from ranibizumab to aflibercept for most eyes. A small proportion may gain vision significantly, but as many lose a similar amount. The treatment interval may increase a modest amount. Whether prospective randomised studies on switching patients from ranibizumab to aflibercept are warranted is doubtful unless a subgroup of patients can be identified that are more likely to benefit than those studied here.

Footnotes

Collaborators: Fight Retinal Blindness Investigators: Eye Associates, Sydney, NSW (Dr A Hunt); Retina Associates, Chatswood, NSW (Dr S Fraser-Bell, Dr C Younan); Marsden Eye Specialists, Parramatta, NSW; Gosford Eye Surgeons, Gosford, NSW (Dr S Young); Gladesville Eye Specialists, Gladesville, NSW (Dr S Young); Eyemedics, Adelaide, SA (Dr S Lake, Dr R Phillips, S Lake, Dr M Perks, Dr Saha); Canberra Hospital, Garran, ACT; Centre for Eye Research Australia, East Melbourne, VIC; Victoria Parade Eye Consultants, Fitzroy, VIC (Dr L Lim); Specialist Eye Group, Hornsby Eye Specialists, Hornsby, NSW (Dr S Lal); ADHB, Auckland, NZ (Dr D Squirrell); University Hospital Zurich, University of Zurich, Zurich Switzerland; Retina Specialist Auckland, NZ (Dr R Barnes, Dr D Sharp); Les Manning Practice, Brisbane, QLD (Dr L Manning); Cairns Eye and Laser Clinic, Cairns, QLD (Dr A Field); Doncaster Eye Center, Doncaster, VIC (Dr L Chow).

Contributors: Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work: DB, AC, PN, JJA, ILM, JMS, APH, RG, RWE, NM and MCG. Acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data for the work: DB, AC, PN, JJA, ILM, JMS, APH, RG, RWE, NM and MCG. Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content: DB, AC, PN, JJA, ILM, JMS, APH, RG, RWE, NM and MCG. Final approval of the version to be published: DB, AC, PN, JJA, ILM, JMS, APH, RG, RWE, NM and MCG. Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved: DB, AC, PN, JJA, ILM, JMS, APH, RG, RWE, NM and MCG.

Funding: This work was supported by a grant from the Royal Australian NZ College of Ophthalmologists Eye Foundation (2007–2009) and a grant from the National Health and Medical Research Council, Australia (NHRMC 2010-1012).

Competing interests: JJA, RG, APH, ILM and MCG are members of advisory boards for Novartis and Bayer. JJA and MCG are also members of advisory boards for Allergan. MCG, JJA, APH and RG report personal fees and others from Novartis, others from Bayer, outside the submitted work. DB and APH received a research grant from Novartis.

Ethics approval: RANZCO HREC and SESIAHS HREC.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: A Hunt, S Fraser-Bell, C Younan, S Young, R Phillips, S Lake, M Perks, Saha, L Lim, S Lal, D Squirrell, R Barnes, D Sharp, L Manning, A Field, and L Chow

References

- 1.Bressler NM. Age-related macular degeneration is the leading cause of blindness. JAMA 2004;291:1900–1. 10.1001/jama.291.15.1900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenfeld PJ, Brown DM, Heier JS, et al. Ranibizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med 2006;355:1419–31 10.1056/NEJMoa054481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown DM, Kaiser PK, Michels M, et al. Ranibizumab versus verteporfin for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med 2006;355:1432–44 10.1056/NEJMoa062655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martin DF, Maguire MG, Fine SL, et al. Ranibizumab and bevacizumab for treatment of neovascular age-related macular degeneration: two-year results. Ophthalmology 2012;119:1388–98 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.03.053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heier JS, Brown DM, Chong V, et al. Intravitreal aflibercept (VEGF trap-eye) in wet age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology 2012;119:2537–48 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holash J, Davis S, Papadopoulos N, et al. VEGF-trap: a VEGF blocker with potent antitumor effects. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2002;99:11393–8 10.1073/pnas.172398299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Papadopoulos N, Martin J, Ruan Q, et al. Binding and neutralization of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and related ligands by VEGF Trap, ranibizumab and bevacizumab. Angiogenesis 2012;15:171–85 10.1007/s10456-011-9249-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stewart MW, Rosenfeld PJ. Predicted biological activity of intravitreal VEGF Trap. Br J Ophthalmol 2008;92:667–8 10.1136/bjo.2007.134874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krohne TU, Liu Z, Holz FG, et al. Intraocular pharmacokinetics of ranibizumab following a single intravitreal injection in humans. Am J Ophthalmol 2012;154:682–6.e2. 10.1016/j.ajo.2012.03.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keane PA, Liakopoulos S, Ongchin SC, et al. Quantitative subanalysis of optical coherence tomography after treatment with ranibizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2008;49:3115–20. 10.1167/iovs.08-1689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forooghian F, Cukras C, Meyerle CB, et al. Tachyphylaxis after intravitreal bevacizumab for exudative age-related macular degeneration. Retina 2009;29:723–31. 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181a2c1c3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martin DF, Maguire MG, Ying GS, et al. Ranibizumab and bevacizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med 2011;364:1897–908. 10.1056/NEJMoa1102673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schaal S, Kaplan HJ, Tezel TH. Is there tachyphylaxis to intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor pharmacotherapy in age-related macular degeneration? Ophthalmology 2008;115:2199–205. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gasperini JL, Fawzi AA, Khondkaryan A, et al. Bevacizumab and ranibizumab tachyphylaxis in the treatment of choroidal neovascularisation. Br J Ophthalmol 2012;96:14–20. 10.1136/bjo.2011.204685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gillies MC, Walton R, Liong J, et al. Efficient capture of high-quality data on outcomes of treatment for macular diseases: the fight retinal blindness! Project. Retina 2014;34:188–95. 10.1097/IAE.0b013e318296b271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cleveland WS, Grosse E, Shyu WM. Local regression models. Statistical Models in S Wadsworth & Brooks/Cole, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arcinue CA, Ma F, Barteselli G, et al. One-year outcomes of aflibercept in recurrent or persistent neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Am J Ophthalmol 2015;159:426–36.e2. 10.1016/j.ajo.2014.11.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang AA, Li H, Broadhead GK, et al. Intravitreal aflibercept for treatment-resistant neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology 2014;121:188–92. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.08.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gillies MC, Campain A, Barthelmes D, et al. Long-term outcomes of treatment of neovascular age-related macular degeneration: data from an observational study. Ophthalmology 2015;122:1837–45. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumar N, Marsiglia M, Mrejen S, et al. Visual and anatomical outcomes of intravitreal aflibercept in eyes with persistent subfoveal fluid despite previous treatments with ranibizumab in patients with neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Retina 2013;33:1605–12. 10.1097/IAE.0b013e31828e8551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rofagha S, Bhisitkul RB, Boyer DS, et al. Seven-year outcomes in ranibizumab-treated patients in ANCHOR, MARINA, and HORIZON: a multicenter cohort study (SEVEN-UP). Ophthalmology 2013;120: 2292–9. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.03.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yonekawa Y, Andreoli C, Miller JB, et al. Conversion to aflibercept for chronic refractory or recurrent neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Am J Ophthalmol 2013;156:29–35.e2. 10.1016/j.ajo.2013.03.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ho VY, Yeh S, Olsen TW, et al. Short-term outcomes of aflibercept for neovascular age-related macular degeneration in eyes previously treated with other vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors. Am J Ophthalmol 2013;156:23–8. e2. 10.1016/j.ajo.2013.02.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika 1983;70:41–55. 10.1093/biomet/70.1.41 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rubin DB. The design versus the analysis of observational studies for causal effects: parallels with the design of randomized trials. Stat Med 2007;26:20–36. 10.1002/sim.2739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]