Abstract

Presumptive somatic cells of the copepod Cyclops kolensis specifically eliminate a large fraction of their genome by the process of chromatin diminution. The eliminated DNA (eDNA) remains only in the germline cells. Very little is known about the nature of the sequences eliminated from somatic cells. We cloned a fraction of the eDNA and sequenced 90 clones that total 32 kb. The following organizational patterns were demonstrated for the eDNA sequences. All do not contain open reading frames. Each fragment contains 1–3 families of short repeats (10–30 bp) highly homologous within families (87%–100%). Most repeats are separated by spacers up to 50 bp long. Homologous regions were found between fragments, motifs from 15–300 bp in length. Among fragments there occur groups in which the same motifs are ordered in the same fashion. However, spacers between the motifs differ in length and nucleotide composition. Ubiquitous motifs (those occurring in all fragments) were identified. Analysis of motifs revealed submotifs, each occurring within several motifs. Thus, motifs may be regarded as mosaic structures composed of submotifs (short repeats). Taken together, the results provide evidence of a high organizational ordering of the DNA sequences restricted to the germline. With this in mind, it appears incorrect to refer to this part of the genome as junk. Moreover, eDNA is redundant for only the somatic cells—its function is to be sought in germline cells.

First discovered in nematodes more than 100 years ago by Boveri (1887), chromatin diminution remains a most enigmatic phenomenon. Chromatin diminution may be regarded as the programmed (i.e., highly repeatable in each cycle of individual development) deletion of DNA (or of entire chromosomes) from the presumptive somatic cells of certain animal species. Chromatin diminution has been analyzed by cytological methods, particularly in nematodes (Goday and Pimpinelli 1984; Tobler 1986; Moritz and Saner 1996; Muller et al. 1996; Niedermaier and Moritz 2000), but also in copepod crustacea (Beermann 1977; Leech and Wyngaard 1996; Wyngaard 2000). A feature of chromatin diminution in the crustacean genus Cyclops is that the somatic and germline chromosome number remains the same.

Chromatin diminution in Cyclops kolensis has been described by Grishanin and Akifyev (Grishanin et al. 1966; Grishanin and Akifyev 2000). At the fourth cleavage division 94% of DNA is expelled from seven presumptive somatic cells; however, the chromosome number (2n = 22) is still the same in both germline and postdiminution somatic cells. The chromosomes of germline cells do not differ sharply in size between each other; they correspond to human chromosomes of the B and C groups. The haploid genome size in Cyclops kolensis is 2.3 pg, whereas after chromatin diminution the somatic genome size is just 0.13 pg. Only one cell, the germline progenitor, retains the full genome. The structure and function of the DNA that is eliminated early in development is very obscure (Akifyev et al. 1998, 2002). It might be selfish (junk) DNA (Doolittle and Sapienza 1980; Orgel and Crick 1980; Myers et al. 2000; Baltimore 2001), or it might perform some role essential for the germline of these species. Sequence sampling of the eliminated sequences may help answer these questions.

Chromatin diminution was studied by molecular biological means in Ascaris. It was found that the loss of repeated and unique nucleotide sequences, particularly of stDNA, does take place (Muller et al. 1996). Importantly, during chromatin diminution in Ascaris, chromosome disintegration occurs.

Even more dramatic events are observed during the macronucleus maturation process in ciliates (Prescott 1983). The macronucleus appears as a sack filled with fragments of chromosomes, each of them harboring not more than one gene and the corresponding minimal regulatory sequences. In Stylonychia, Oxytricha, and Euplotes species, macronuclei contain from 2% to 4% of the nucleotide sequences present in the chromosomes of micronuclei. In past studies in the field of diminution in Ascaris and Infusoria, all of the analyses basically involved comparative analysis of structural genes and their adjacent genomic regions in chromosomes prior to and after diminution. These exceptionally interesting works did not advance the understanding of one of the major mysteries of eukaryotes, namely, the C-value paradox. In particular it was unclear whether DNA sequences restricted to the germline could have some special function(s), or whether they were some sort of genetic rubbish.

Chromosomes of Cyclopoidae do not disintegrate during chromatin diminution; still, the eliminated DNA (eDNA) accumulates in special granules (Fig. 1; Grishanin et al. 1966). This eDNA can be isolated via microdissection followed by molecular cloning (Fig. 2). Thus, Cyclopoidae, in particular C. kolensis, represent an excellent model for the investigation of DNA sequences restricted to the germline. Sequencing of these clones has shown that the eDNA contains a complex of repetitive sequences.

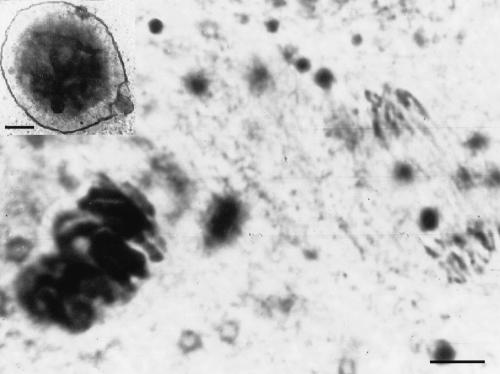

Figure 1.

A microphotograph of the C. kolensis chromosomes in the germline cells (left) and at anaphase of the somatic cells (right) during diminution division. An electron microscope photograph of the granules of eDNA (bar = 5 μ) (top upper corner). A poreless, one-layer membrane surrounds the granule (bar = 1 μ).

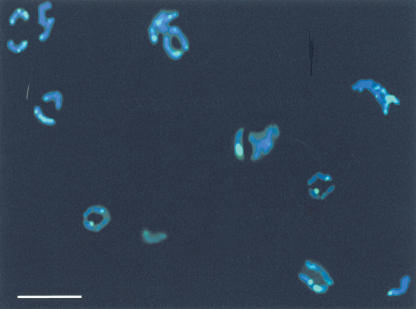

Figure 2.

Extraction of granules of eliminated chromatin with a micromanipulator during the fifth cleavage division.

Results

A general characterization of Cyclops kolensis eDNA

Ninety clones were isolated and sequenced. Numerous sites of almost all prediminuted chromosomes were labeled by means of in situ hybridization using the total pool of clones of eDNA as a probe (Fig. 3). The localization of the signals demonstrates that eliminated DNA is located in different sites: in some chromosomes it is near telomeres, in others it is in pericentric regions or in the regions not related to either telomeres or centromeres.

Figure 3.

In situ hybridization of clones isolated from the C. kolensis eDNA with prediminuted chromosomes. Brightly stained regions (greenish) correspond to eDNA location (bar = 5 μ).

The lengths of the sequenced eDNA fragments varied between 163 and 650 bp; the average was 351 bp and the total length sequenced was 31,564 bp. Multiple alignments demonstrated that 57 of the 90 cloned sequences are present more than once in the sample, with copy numbers between two and nine, with 19 groups of multiple clones (http://www.genebee.msu.su/services/malign_reduced.html). Thirty-three clones were singletons. Fifty-two different clones, representing 19,400 bp, were, therefore, available for analysis; their average length was 373 bp. The fact that duplicate clones were found in such a small sample of the eDNA indicates that this DNA is remarkably homogeneous in sequence (assuming random PCR priming).

The sequenced DNA has a high A+T composition (∼60%, but reaching 76.4% in clone 19), only two clones having an A+T/G+C ratio close to 50%. No significant coding regions were included in any of the clones.

Homologous sequences within single clones

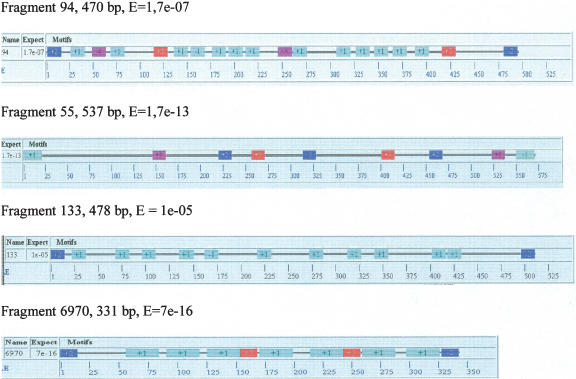

The major characteristic of the sequences of the 52 clones is the presence of abundant short (7–34-bp) repeats, belonging to several different repeat families. Between one and three families of repeat were found in each clone, with family copy numbers being up to 13 per clone. To illustrate this sequence organization, four of the clones will be described in detail (Fig. 4; http://meme.sdsc.edu/meme/website/meme.html).

Figure 4.

Repetitive sequences within eDNA fragments. Blocks of the same color denote homologous repeats within a fragment, not between fragments. Numbers within blocks denote repeat numbers. The sign before a number indicates the orientation of a repeat (direct or inverted). Numbers on the scale indicate length expressed as nucleotide pairs. E = theoretical expectation. For each fragment, the color of the blocks was taken by chance; that is, blocks of the same color in different fragments belong to different repeats.

Clone 94 (470 bp) contains the greatest number of repeats, 17, composed of three families: 7-bp-long (two copies), 8-bp-long (two copies), and 15-bp-long (13 copies, one of which is inverted). The consensus sequence of the 15-bp repeat is 5′-GGAACAAGAAAACAA-3′. Its AT content is 67%, close to the average estimate; this sequence is very purine-rich (87%). The average degree of homology among the members of this family is 89%; sequence copies showing 100% homology to the consensus sequence occur. The length of the spacers between the repeats varies between 1 and 52 bp.

A 537-bp clone (#55) contains seven repeats belonging to three families (of 7, 8, and 14 bp). A remarkable feature of this fragment is the 100% homology between repeats composing it. Repeat spacer size ranged from 13 to 128 bp.

Clone 133 (478 bp) includes 11 repeats (one inverted with respect to the others) of the 11-bp sequence 5′-ACGGAAGAAGA-3′. Similarity between the repeats was 90%–100% (94% on average). The 100% homologous sequences are not consistently neighbors; they were occasionally separated by repeats containing substitutions and rather long spacers that stretched from 2 to 48 bp in this particular clone.

Clone 6970 (331 bp) contains seven copies of one of the longest repeats, 29 bp. This sequence also shows very high homology, 94%, on average, and three repeats are identical. The spacers in this fragment are from 2 to 16 bp in size.

Homologous sequences between clones

We next determined the similarities in sequence between the 52 different clones (sequence set S1). As shown in Figure 5, it is clear that the pattern of very short repeats seen within clones is replaced by more extensive regions of sequence similarity between clones. This implies that the short repeats characteristic of individual clones represent fragments of longer repetitive motifs.

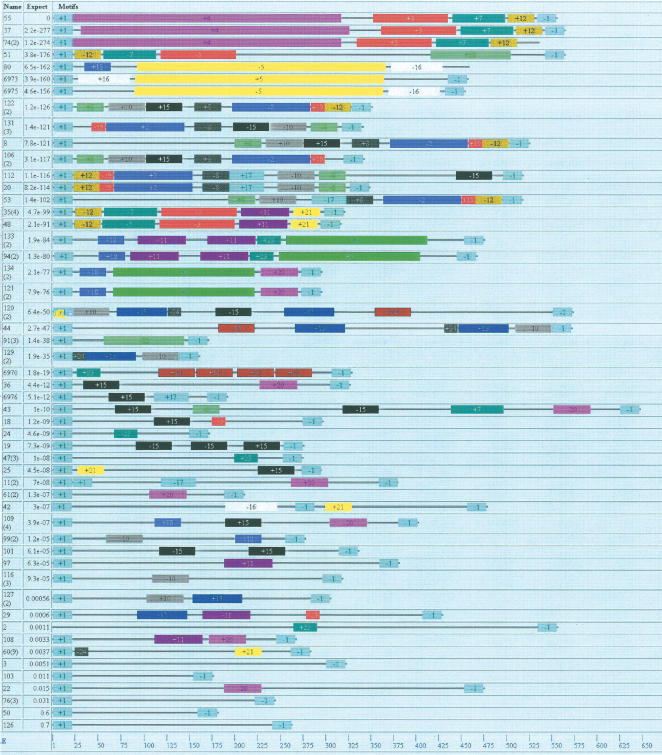

Figure 5.

A schematic representation of repetitive sequences in Cyclops kolensis eDNA. Twenty-four repeat families are denoted by different colors. Numbers denote family numbers. “+” before the number indicates that the repeat is in direct orientation; “–” before it indicates that the repeat is in inverted orientation. Fragment length expressed as nucleotide pairs is given at the bottom of the scale. Clone number is given in the first column; theoretical expectation is given in the second. Primer sequences are indicated by number 1.

Twenty-four repeat motifs, each one occurring in at least three DNA fragments, were identified (Table 1). The length of the motifs vary widely from 15 to 296 bp. Repeats longer than 100 bp occur in single copies within a fragment. Shorter ones occur in multiple copies. Thus, motif 15 (40 bp) exists in 1–3 copies in 13 different clones. Only five short clones (<300 bp) did not contain repeat motifs.

Table 1.

DNA motifs found in the first sampling (S1)

| Motif number | Sequence size, -bp | Motif with best possible match |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 21 | CGACTCGAGGGGGTTATGTGG |

| 2 | 86 | GGAGAGTAACATTGAGAAAACTCTCTCCCTATTTAGGTTACGCGCCTGAAGATTTTCTGTTGAATCTCTGCAAACTATCAGTATAC |

| 3 | 83 | ACACTTTCTTGCAGAGATGCCCACTGTTTGGCATTCAACTTGAGAATGGCCTCTCTACTCCTTTTTGCTTTTTGAAATCGAAT |

| 4 | 296 | AGGAGGAGGTTGAGGTTGAGGATTGACCAGAAGATGTTGGAAGTGTTCTTGTAAAGCAGGATAGTGTTTGAGTTCAGTAGGACACGAGTACACTAGGATGTATGAACAGGGATCAAATTCCACGTAGGGGTCACCTGTTAACACGATGTTTCTTTCTTGAAAGGATAAGCTTTCCAAAAATTTTCTTCTGTTGTGGATCCAAGCTGGTTGTTTAACATTTGGTAATTTGAGTGGAAGGCCAAAGTCGTCACATTCGTACCTTGGTCCAATTTGATTTGGTTGCCAGCCTCTTTCGA |

| 5 | 274 | TTTTCTTCTCGGTGTTGCGCCGCCATTGGATAATGGGTCTGGTCCTGGGTAAATTGTTGGCGGTCCTTTCCACGGCTTCCAATAATTCTTCGCTGGTGAGTTTGTCCAACCATCCATATCCGGAAAAACGGTAGTTGTAACTTCGTAGAAGTCCGTTTCCGAATAGTTGTTGTGTTGAGTACCCACGGTGGGAAGCGGTGAGTTGATCCTCTTGATCTTCTTCTTCTTCTTCTTCCTGACAGACAGGGGCAATTCCTTGTGTGTTTCCATGTTC |

| 6 | 29 | AGGGGGCTTTCTCGGCTCCAAGGTGCATG |

| 7 | 58 | GAGCATCCAAGCCAGCTTCAAAATTTGTTTTTACAGTGGCATCTTCAAACTGCTTTTT |

| 8 | 30 | TGCTGCGACCTCCTGACACTATTTCAGGCT |

| 9 | 156 | AAAAAGATACAATCACCGAACTACAAGCCCTCTAAGGGGACCAGAAATCAGTCACACGCACCTAGCCCACCAGAGGCGACACAGCAAAAGGACACCTGCGACAACAACACCGAGGAGGCAGGGCAGAAGAAGCCACAAGAAGAGGATTGACCACCC |

| 10 | 41 | TTCGTATTCTACTAACCAACAATTGACAGTGGTAAGAACGT |

| 11 | 53 | AAGAAACAAAAGTCGGGTCAACTTGGGTCAACGGAAGAGGATGGCAACCAAAG |

| 12 | 29 | GCAATTGGGTGTTGGGTCCCATTTACACT |

| 13 | 55 | GGGATTGAGTGGGTTGGTTTGTAGACTGAACCTTTTCTTACTTGCTTAGCTTCAG |

| 14 | 40 | CCAATTTCTGGAAAAAGAATGTCCCACCAAAGTGACAGCA |

| 15 | 40 | CTATTTTGAGACAGAACTGAATGGAAGTATTGAAATGACG |

| 16 | 57 | GAGATTCCGACTGATACCACTGCCTTGGGTATCCTTCCAGGCACCAGAAAACTTCTT |

| 17 | 38 | TCGGTACATTTCCCTTAATTTCAATACTTTCATTTAAA |

| 18 | 29 | GCACCAGGATCGACACAAGACCAAAACAT |

| 19 | 15 | ATACAACCTAGTTTC |

| 20 | 41 | AGAAAAGGACAATCAAAAAGAACAAGGCCAAATAGAATCAA |

| 21 | 29 | TGGACCCCGGTACAAATGTGATGACTTTG |

| 22 | 88 | GATCCCTGCTCATACATCCTAGTGTACTCATGCCCAACTGAGCTCAAACACTATCCTGCCCTACAAGCACACTTCCAGCACCTTCTGG |

| 23 | 26 | ACAATCTCTGGTCAGGAAGGAGGCCC |

| 24 | 15 | TCGAGCGGTTTCTTC |

See also Figure 5, where these motifs are highlighted in color.

We could not establish any general patterns for motif location, with the exception that motif 12 (129 bp) was always very close (1–3 bp) to the primer sequence.

Clones with the same motifs

Among the eDNA fragments shown in Figure 5, groups of 2–3 fragments are distinguishable. In these groups, the same motifs are ordered in the same way. Illustrative are fragments 55, 37, and 74, constituting one group, and fragments 80, 6973, and 6975, representing a different group. Within groups the clones differ in length, spacer sequences, and spacer lengths.

The clones of one of these groups can be schematically represented as:

55 (557 bp): 1 (P+) – (+4) 35 (+3) 5 (+7) 3 (+12) 3 (P–) 2

37 (566 bp): 1 (P+) 9 (+4) 35 (+3) 5 (+7) 3 (+12) 3 (P–) 2

74 (537 bp): 1 (P+) – (+4) 17 (+3) 5 (+7) 2 (+12) 25 (P–) 2

In this scheme, the motif number is in parentheses, the sign before the number denotes the orientation of the repeat (“+” indicates direct, “–” indicates inverted). Spacer length is given between the parentheses; P+ and P– denote primer sequences. As the scheme shows, there is no spacer between primer and motif (+4) in fragments 55 and 74, whereas the spacer between motifs (+4) and (+3) is shorter by 18 bp in fragment 74 than in the others. Moreover, the 35-bp spacers in fragments 55 and 37 show only 63% homology; in contrast, homology within the neighboring motifs is as high as 98%. Many fragments are almost entirely composed of motifs. For this reason, based on DNA analysis by fragment reassociation, the fragments of these clones would be referred to the same family with repeats of average length. In actual fact, these are different sequences, and the uniqueness of each is due to the organizational features of the spacers between the sequences. The same differences impart uniqueness to fragments 133 and 94, in which motifs are ordered in the same way despite their having different short repetitive elements (Fig. 5). By and large, however, sequences within a motif were found to be the same.

Search for new motifs

Following this analysis we made a nonredundant data set of sequences (data set S2), by discarding sequences of clones that were very similar. This nonredundant set included 37 clones (average length 380 bp) totaling 14,047 bp. This set was used to identify new sequence motifs.

Twelve motifs from 21 to 113 bp in length were identified by a comparison of the sequences of these 37 clones (Supplemental Fig. 1). These motifs are shorter than those previously identified (cf. Fig. 5, Supplemental Fig. 1). Clone 37 can be used as an exemplar: it consists of 14 short repeats of three families (Fig. 4; first line). A sequence of 11 bp occurs most frequently (eight times). Its consensus is 5′-GAGACCAAAGT-3′. The average homology degree is 91%, and it is 73% purine.

Comparisons of the distribution patterns in the complete (S1) and nonredundant (S2) sets show that the structure of the repeats is very different: none of the pre-existing motifs remained (see Fig. 5, Supplemental Figs. 1,3). The longest, 4(1), fell apart into three motifs, 6(2), 10(2), and 5(2); (the sample number is given in parentheses). The motif 6(2) is the longest motif (113 bp) identified in the sampling. Sequences highly homologous to this motif can also be found in four other clones (Supplemental Fig. 1). Motif 10(2) is 21-bp-long (5′-GAAGAAGCAG CAAAAGAAAAT-3′), it is 67% A+T content and 86% purine. In clone 37, the repeat occurs in two copies; one is a part of motif 4(1), the other is a spacer intervening between motifs 4(1) and 3(1). The motif may, with good reason, be called ubiquitous, because it has 29 sites in 16 clones showing an average homology of 87%. Clone 133 contains the greatest number of copies of motif 10(2), six, with an average 90% homology.

Motif 5(2) is also very abundant in the nonredundant set. Its length is 57 bp, A+T content and purine percentage being about 50%. In this set, the repeat occurs in 12 copies in eight clones and in two in clone 37. The second copy encompasses parts of motifs 7(1) and 12(1) and an intervening spacer. Finally, motif 3(2) of 106 bp (A+T, 61%; 58% purine) is present in five copies in four clones.

It is worth noting that the nonredundant set also contains groups of fragments with the same motifs in the same orderly fashion. Examples are fragments 37 and 51. Their locations are very similar in the nonredundant set, although weakly so in the full clone (S1) set.

Thus, a complex pattern of repeat interspersion for eDNA emerges: Long motifs are comprised of shorter ones, and spacers can become elements of motifs.

Search of common motifs

The two sequence sets (S1 and S2) were tested to identify the motifs shared by all the fragments of a sample, in other words, the motifs that occur on at least one occasion. Such sequences were identified (Supplemental Fig. 2).

This applies in the first place to primer sequences. The five-member 5′-CTGAA-3′ is adjacent to half of these repeats and, for this reason, a repeat either of 22 bp (the size of a primer) or of 27 bp lies at the ends of the fragments.

Two other common motifs, U3(1) and U4(1) were found in the full clone set [indicated by (1); sequences in the nonredundant set (S1) are indicated by (2)]. The former is 21-bp-long (5′-CATACAACCTAGTTTCATTGT-3′), 67% A+T. This motif occurs in two copies in clone 51 and in a single copy in the other clones. Motif U4(1) is present in a single copy in each fragment, except in clone 37, where it occurs in two copies. Its length is 11 bp (5′-CAACAGAAAAT-3′); A+T, 73%, 64% purine. Analysis of the “metamorphosis” of clone 37 demonstrated that motif U3(1) is a small segment of motif 6(2) and, therefore, of 4(1) as well. Motif U4(1) is a part of motif 10(2), which is also a part of repeat 4(1). Hence, both ubiquitous repeats of the full sequence set are actually parts of motif 4(1). Ubiquitous repeats U3(1) and U4(1) exemplify well how sequences first revealed in the analysis of individual clones as spacers (i.e., sequences not repetitive in a given clone), say, in clone 37, in a further analysis were perceived as ubiquitous, occurring in repeats throughout many other regions of the genome.

New ubiquitous repeats U2(2) and U3(2) appeared in the second sample (S2). Motif U2(2) is 15-bp-long (5′-CCG ACTCGAGTCGGA-3′); motif U3(2) is 21-bp-long (5′-AAAA TGAAAAAGAAGCAGAG-3′); 67% A+T, 86% purine. In clone 37, the first copy is adjacent to the primer sequence, and the second is a part of motifs 3(1) and 3(2). The second motif is also a part of the two latter motifs.

Different motifs contain submotifs, homologous repetitive sequences

A thorough analysis of motif location in both sequence sets within a clone (clone 37; Supplemental Fig. 3) revealed that new motifs are the composite elements of larger motifs and also that the spacer region of a sample can become motifs of the other sample. For example, motif –10(2) arose at the site of the spacer between motifs +4(1) and +3(1) in S1.

We next turned to the question of whether motifs of the two sets contain common elements. We adopted the procedure of searching motifs within motifs. For this purpose, all the motifs (including the ubiquitous) in both sequence sets were tested for the presence of repeats (Table 2, Supplemental Fig. 4).

Table 2.

Submotifs of the complete (S1) and the nonredundant (S2) sequence sets

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (1) | 1 (-) | 100 | 102 | |||||||

| 4 (1) | 1 (-) | 86 | 3 | |||||||

| 9 (1) | 1 (+) | 76 | 4 | |||||||

| 14 (1) | 1 (+) | 76 | 6 | 117 | ||||||

| 22 (1) | 1 (+) | 81 | 2 | |||||||

| R1 | CCACATAACCCACTCGAGTCG | 21 | 43 | 43 | 11 | U1 (1) | 1 (+) | 95 | 52 | |

| U2 (1) | 1 (+) | 91 | 52 | 104 | ||||||

| 1 (2) | 1 (+) | 100 | 4 | |||||||

| 6 (2) | 1 (-) | 91 | 3 | 11 | ||||||

| 8 (2) | 1 (+) | 76 | 4 | |||||||

| U1 (2) | 1 (+) | 100 | 37 | 37 | ||||||

| 4 (1) | 1 (+) | 100 | 7 | |||||||

| 7 (1) | 1 (-) | 100 | 6 | 15 | ||||||

| 22 (1) | 1 (-) | 100 | 2 | |||||||

| R2 | AAACTAGGTTGTATG | 15 | 67 | 60 | 07 | U3 (1) | 1 (-) | 100 | 52 | 52 |

| 2 (2) | 1 (-) | 100 | 4 | |||||||

| 3 (2) | 1 (+) | 100 | 4 | 11 | ||||||

| 6 (2) | 1 (+) | 100 | 3 | |||||||

| 2 (1) | 1 (-) | 86 | 7 | |||||||

| 3 (1) | 2 (-+) | 76; 100 | 6 × 2 = 12 | |||||||

| 4 (1) | 2 (++) | 81; 76 | 3 × 2 = 6 | |||||||

| 5 (1) | 2 (++) | 76; 76 | 3 × 2 = 6 | |||||||

| 7 (1) | 1 (+) | 81 | 6 | 64 | ||||||

| 9 (1) | 1 (-) | 81 | 4 | |||||||

| 10 (1) | 1 (-) | 76 | 10 | |||||||

| R3 | GTCTTCTCCATGTTGCTTTCT | 21 | 57 | 19 | 20 | 11 (1) | 1 (-) | 71 | 7 | |

| 20 (1) | 1 (-) | 91 | 6 | |||||||

| 2 (2) | 1 (+) | 86 | 4 | |||||||

| 3 (2) | 2 (-+) | 100; 95 | 4 × 2 = 8 | 33 | ||||||

| 4 (2) | 2 (+-) | 91; 76 | 4 × 2 = 8 | |||||||

| 5 (2) | 1 (+) | 81 | 8 | |||||||

| 12 (2) | 1 (+) | 81 | 5 | |||||||

| U3 (2) | 1 (-) | 95 | 37 | 37 | ||||||

| GGAGGTTGAGGTTGAGGATT | 4 (1) | 1 (+) | 100 | 3 | ||||||

| R4 | GACCAGAAGCTGCTGGAAGT | 57 | 51 | 65 | 03 | 5 (1) | 1 (+) | 100 | 3 | 6 |

| GTTCTTGTAAAGCAGGA | 6 (2) | 1 (+) | 100 | 3 | 3 | |||||

| 2 (1) | 1 (+) | 100 | 7 | |||||||

| 10 (1) | 1 (+) | 100 | 10 | 22 | ||||||

| 13 (1) | 1 (-) | 100 | 5 | |||||||

| R5 | TCTACAAACCA | 11 | 64 | 45 | 07 | 4 (2) | 1 (+) | 100 | 4 | |

| 5 (2) | 1 (+) | 82 | 8 | 21 | ||||||

| 7 (2) | 1 (-) | 100 | 4 | |||||||

| 13 (2) | 1 (-) | 91 | 5 | |||||||

| 15 (1) | 1 (+) | 100 | 7 | |||||||

| R6 | AATGGAAGTATTGAAATTAAG | 21 | 76 | 71 | 03 | 17 (1) | 1 (-) | 100 | 3 | 10 |

| 9 (2) | 1 (+) | 100 | 3 | 3 | ||||||

| R7 | AGGCGCGTAACCTAAATAGGG | 21 | 48 | 67 | 02 | 2 (1) | 1 (-) | 100 | 7 | 7 |

| 2 (2) | 1 (+) | 100 | 4 | 4 | ||||||

| 2 (1) | 1 (+) | 100 | 7 | |||||||

| 4 (1) | 1 (+) | 90 | 3 | |||||||

| 5 (1) | 1 (+) | 80 | 3 | 23 | ||||||

| R8 | TTTTCTGTTG | 10 | 70 | 20 | 07 | 11 (1) | 1 (-) | 80 | 7 | |

| 16 (1) | 1 (-) | 90 | 3 | |||||||

| U4 (1) | 1 (-) | 100 | 52 | 52 | ||||||

| 10 (2) | 1 (-) | 90 | 10 | 10 | ||||||

| R9

|

TGCTGCGACCTCCTGTCACTA

|

21

|

43

|

33

|

02

|

8 (1) | 1 (+) | 100 | 7 | 7 |

| 9 (2) | 1 (+) | 100 | 3 | 3 |

Designations of the columns: 1. Submotif name; 2. Submotif consensus sequence; 3. Sequence size, bp; 4. A+T-pair content, %; 5. Purine content, %; 6. Number of sites; 7. Motifs in which submotifs are located; 8. Number of copies and orientation (in parentheses) of a submotif in a motif; 9. Percentage of homology to the S1 set motifs; 10. Copy number of a copy in a sample multiplied by copy number of a submotif in the given motif; 11. Total copy number in a sequence sample.

Forty-four motifs from 11 to 296 bp in length were analyzed. Homologous regions were found in 35 motifs (Supplemental Fig. 4). Nine submotifs from 10 to 57 bp were revealed. Their characterization is given in Table 2. The A+T content in the submotifs varied from 43% (R1 and R9) to 76% (R6). The content of purines reached 81% (R3 complementary strand). Submotif R3 is the most widespread (besides a primer sequence, submotif R1). It is present in a single copy or two copies in nine of the 24 motifs in the first sample. In all, the S1 submotif has 67 copies.

It should be noted that six of the nine motifs from 11 to 57 bp show 100% homology with all of the motifs of sample S1 where they occur.

The number of submotifs within a motif reaches G: R1-1, R2-1, R3-2, R4-1, R8-1. Their full length is about half of the motif size. In motif 2(1), which is 86-bp-long, four submotifs occupy 73% of it. It may be concluded that motifs are mosaics of submotifs.

Discussion

This is the first study of the molecular structure of the DNA sequences restricted to the germline in C. kolensis, a species subject to chromatin diminution during development. The part of the genome discarded from the presumptive somatic cells (eDNA) is a most vivid example of redundant DNA in the eukaryotes. In Shapiro's (1992) view, chromatin diminution may be seen as a case of genetic engineering in nature. Chromatin diminution occurs during the fourth cleavage division and occurs in seven of the eight cells, that is, to the blastomeres that contribute to the soma. The complete genome is faithfully retained in the sole cell that will be the progenitor of the germ cell line.

In this study, we demonstrate that eDNA contains considerable sequence complexity and organizational variability. eDNA is composed of a mixture of repeated DNA elements and spacers interspersed among each other, many direct and inverted repeats with a complex internal structure present within the same fragment and also scattered throughout the genome, divergence of eDNA with a prevalence of AT over GC pairs, and frequently marked asymmetry of DNA strands with respect to purines and pyrimidines. Of particular interest were the observations that many fragments (repeats) consist of submotifs, that is, they have a mosaic structure.

Viewed broadly, every germline-limited DNA fragment we cloned has a unique structure. This is evidence supporting the hypothesis we advanced earlier (Akifyev et al. 2002) that eDNA may play a role in the genetic isolation mechanism preventing the synapsis of homologous chromosomes in meiosis of interspecific Cyclops hybrids.

On the other hand, the mutational process in the germline cells of Cyclops kolensis (if even the eDNA is completely neutral) would result in destruction of its ordered repeated structure, because it is not under control of natural selection. In this case even in isolated populations of this species, Cyclops with different structures of the germline-limited DNA could mate. However, it could bring about distortion of synapsis of homologous chromosomes and, further, aneuploidy.

Indeed, the germline-limited DNA sequences have a complex structure, yet conforming to a strict pattern where the sequences do not tend to markedly diverge. Support was provided by multiple highly homologous repeats, that is, sequences that have retained their structural identity for a long time. Recent data point to an extremely low level of spontaneous chromosome aberrations in the early cleavage divisions in the Cyclops, particularly in C. kolensis (Grishanin et al. 2002). This indicates that there may be a specific mechanism protecting the genome from spontaneous mutations.

The eDNA and the portion of DNA remaining in the soma cannot be regarded as entirely independent parts of the common genome. The structural genes and the regulatory sequences needed by the somatic tissues are apparently not lost. We presume that specific endonucleases cleave the eDNA from the germline chromosomes. The molecular structure of the sites of cleavage is as yet unknown. Quite plausibly, the sites compose a single common sequence. It has been estimated that the C. kolensis genome may harbor thousands of chromatin diminution sites (Grishanin et al. 1966). If so these, and perhaps the nature of the eDNA sequences themselves, constrain the evolution of the eDNA sequences themselves. Whether these sequences undergo concerted evolution (Zimmer et al. 1980; Hurles and Jobling 2003) or whether their similarities reflect a very recent origin is unknown.

It is hoped that further characterization of the eDNA sequences will fulfill the wish of Wyngaard and Gregory (2001)— the process of chromatin diminution “will become newly illuminated and eventually understood.”

Methods

Females of Cyclops kolensis Lilleberg 1901 whose egg sacs contained embryos were collected from a pond in the Vorob'evy Gory (Moscow) in April 2000. They were identified according to Monchenko (1974). The egg sacs of C. kolensis were fixed in a 3 ethanol: 1 acetic acid mixture for 1 h at 4°C. The preparations were Feulgen-stained as described by Rasch (1974). Hundreds of females of C. kolensis were collected for cytological analysis. The preparations were examined with a Zeiss microscope at 1000× magnification.

The granules were microdissected under an inverted microscope Axiovert 100 (objective 100×, ocular 10×, Zeiss), using a retracted glass needle under the control of a micromanipulator MR (Zeiss), as shown in Figure 2. The DNA extracted from the granules, collected with a micromanipulator, was amplified by PCR using a partly degenerate primer, DOR PCR, as described elsewhere (Telenius et al. 1992). The PCR product was labeled with biotin-11-dUTP for 17 additional cycles (Rubtsov et al. 1996).

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and signal detection (avidine-FITC/biotinylated antiavidine/avidine-FITC) were done according to the standard methods (Lichter et al. 1988; Karamysheva et al. 2001). The preparations designed for FISH were preincubated in RNAase solution (0.1 mg/mL) in 2×SSC for 1 h at 37°C, followed by dehydration and fixation in 1% form-aldehyde in phosphate buffer for 10 min at room temperature. The cytological preparations were denatured in 2×SSC for 2 min at 70°C. After in situ hybridization, the cytological preparations were stained with DAPI (4,6-diamidino-2phenyl-indole).

The FISH results were analyzed with a luminescent Axioscope 2 microscope equipped with a CCD camera, a filter set, and image-processing software (Metasystems).

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. M. Ashburner for help with DNA sequencing and for his comments on the manuscript, Prof. G. Wyngaard for her kind and most valuable remarks on the general aspects of the chromatin diminution process, A.A. Mironov for discussing the results, and T. Ketova for the technical assistance. The work in Moscow was supported by grants from RFBR (03-04-48133a) and “Genetic aspects of evolution of biosphere” programs (A.A.). The work in Novosibirsk was supported by grants from the programs “Origin and evolution of biosphere” and “Molecular and cellular biology” (I.Z.).

Article and publication are at http://www.genome.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gr.2794604.

Footnotes

[Supplemental material is available online at www.genome.org. The sequence data from this study have been submitted to GenBank under accession nos. AY533039–AY533099.]

References

- Akifyev, A.P., Grishanin, A.K., and Degtyarev, S.V. 1998. Chromatin diminution associated with reorganization of the molecular structure of the genome: Evolutionary aspects. Russ. J. Genet. 417: 709-718. [Google Scholar]

- Akifyev, A.P., Grishanin, A.K., and Degtyarev, S.V. 2002. Chromosome diminution is a key process explaining the eukaryotic genome size paradox and some mechanisms of genetic isolation. Russ. J. Genet. 5: 486-495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltimore, D. 2001. Our genome unveiled. Nature 409: 814-816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beermann, S. 1977. The diminution of heterochromatic chromosomal segments in Cyclops (Crustacea, Copepoda). Chromosoma 60: 297-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boveri, T. 1887. Über Differenzierung der Zellkerne während der Furchung des Eies von Ascaries megalocephala. Anat. Anz. 2: 297-344. [Google Scholar]

- Doolittle, W.F. and Sapienza, C. 1980. Selfish genes, the phenotype paradigm and genome evolution. Nature 284: 601-603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goday, C. and Pimpinelli, S. 1984. Chromosome organization and heterochromatin elimination in Parascaris. Science 224: 411-413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grishanin, A.K. and Akifyev, A.P. 2000. Interpopulation differentiation within C. kolensis and C. strenuus strenuus (Crustacea: Copepoda): Evidence from cytogenetic methods. Hydrobiology 417: 37-42. [Google Scholar]

- Grishanin, A.K., Khudoli, G.A., Shaikhaev, G.O., Brodskii, V.Y., Makarov, V.B., and Akifyev, A.P. 1966. Chromatin diminution in Cyclops kolensis (Copepoda, Crustacae) is a unique example of genetic engineering in nature. Russ. J. Genet. 32: 492-499. [Google Scholar]

- Grishanin, A.K., Degtyarev, S.V., and Akifyev, A.P. 2002. Chromosomal radiosensitivity as associated with chromatin diminution in Cyclops (Crustacea, Copepoda). Rus. J. Genet. 38(4): 468-472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurles, M.E. and Jobling, M.A. 2003. A singular chromosome. Nat. Genet. 34: 246-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karamysheva, T.V., Matveeva, V.G., Shorina, A.R., and Rubtsov, N.B. 2001. Clinical and molecular cytogenetic analysis of rare case of mosaicism with partial monosomy 3p and partial trisomy 10q in human. Russ. J. Genet. 37: 1-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leech, D.M. and Wyngaard, G.A. 1996. Timing of chromatin diminution in the free-living, fresh-water Cyclopidae (Copepoda). J. Crustacean Biol. 16: 496-500. [Google Scholar]

- Lichter, P., Cremer, T., Tang, C.J., Watkins, P.C., Manuelidis, L., and Ward, D.C. 1988. Rapid detection of human chromosome 21 aberrations by in situ hybridization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 85: 9664-9668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monchenko, V.I. 1974. The fauna of Ukraina. Naukova Dumka, Kiev, USSR

- . Moritz, K.B. and Saner, H.W. 1996. Boveri's contributions to developmental biology—A challenge for today. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 40: 27-47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller, F., Bernand, V., and Tobler H. 1996. Chromatin diminution in nematodes. BioEssays 18: 133-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers, E.W., Sutton, G.G., Delcher, A.L., Dew, I.M., Fasulo, D.P., Flanigan, M.J., Kravitz, S.A., Mobarry, C.M., Reinert, K.H., Remington, K.A., et al. 2000. A whole genome assembly of Drosophila. Science 287: 2196-2204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niedermaier, J. and Moritz, K.W. 2000. Organization and dynamics of satellite and telomeric DNA in Ascaris: Implication breakdown of compound chromosomes. Chromosoma 109: 439-452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orgel, L.E. and Crick, F.H. 1980. Selfish DNA: The ultimate parasite. Nature 284: 604-607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prescott, D.M. 1983. The C-value paradox and genes in Ciliated Protozoa. Modern Cell Biol. 2: 329-352. [Google Scholar]

- Rasch, E.M. 1974. The DNA content of sperm and hemocyte nuclei of the silkworm, Bombyx mori L. Cromosoma 45: 1-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubtsov, N., Senger, G., Kucera, H., Neumann, A., Kelbova, K., Junker, K., Beensen, V., and Claussen, U. 1996. Interstitial deletion of chromosome 6q: Report of a case and precise definition of the breakpoints by microdissection and reverse painting. Hum. Genet. 97: 705-709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, J. 1992. Natural genetic engineering in evolution. Genetica 86: 99-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telenius, H., Carter, N.P., Bebb, C.E., Nordenskjold, M., Ponder, B.A., and Tunnacliffe, A. 1992. Degenerate oligonucleotide-primed PCR: General amplification of target DNA by single degenerate primer. Genomics 13: 718-725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobler, H. 1986. The differentiation of germ and somatic cell lines in nematodes. In Germ line-soma differentiation (ed. W. Henning), pp. 1-69. Springer-Verlag. New York. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wyngaard, G.A. 2000. The contribution of U.R. Einsle to the taxomomy of the Copepoda. Hydrobiology 417: 1-10. [Google Scholar]

- Wyngaard, G.A. and Gregory, T.R. 2001. Temporal control of DNA replication and the adaptive value of chromatin diminution in Copepods. J. Exp. Zool. 291: 310-316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer, E.A., Martin, S.L., Bekerly, S.M., Kan, Y.W., and Wilson, A.C. 1980. Rapid duplication and loss of glues coding for the 2 chain of hemoglobin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 77: 2158-2162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

WEB SITE REFERENCES

- http://www.genebee.msu.su/services/malign_reduced.html; AliBee-MultipleAlignment.

- http://meme.sdsc.edu/meme/website/meme.html; MEME program.