Abstract

Cryptococcosis is an invasive fungal infection that is common in immunocompromised patients. A 22‐year‐old woman with Ewing sarcoma in the right proximal humerus was treated by resection and chemotherapy. Computed tomography detected a small nodule in her right upper pulmonary lobe after completion of her chemotherapy. With the presumptive diagnosis of pulmonary metastasis, she underwent resection. Evaluation of the resected specimen revealed pulmonary cryptococcosis, and the patient was treated with oral fluconazole for 18 weeks. Extensive chemotherapy for high‐grade sarcoma is a possible risk factor for pulmonary cryptococcosis. The differential diagnosis of a nodular pulmonary lesion that develops in a patient undergoing treatment for high‐grade sarcoma is important.

Keywords: Chemotherapy, Ewing sarcoma, pulmonary cryptococcosis

Introduction

Pulmonary cryptococcosis is a fungal infection that commonly occurs in immunocompromised hosts, including patients with HIV infection. Pulmonary cryptococcosis rarely occurs in immunocompetent hosts 1.

Ewing sarcoma is the second‐most frequent bone sarcoma after osteosarcoma in patients younger than 20 years. It is characterized by high metastasizing potential. Advances in treatments that use intensive multiagent chemotherapy have contributed to prolonged survival.

Here, we report a patient with Ewing sarcoma in the right proximal humerus, who was treated by chemotherapy. After her chemotherapy regimen, she underwent resection for a small pulmonary nodule that was thought to be metastatic sarcoma, but which was subsequently diagnosed as pulmonary cryptococcosis.

Case Report

A 22‐year‐old woman was seen for pain in her right shoulder. Plain radiographs of the proximal humerus revealed a poorly defined, irregular osteolytic lesion (Fig. 1A). T1‐weighted magnetic resonance imaging showed a lesion with low‐signal intensity, and T2‐weighted imaging showed heterogeneous low‐ to high‐signal intensity (Fig. 1B). Ewing sarcoma was diagnosed from an open biopsy specimen.

Figure 1.

A 22‐year‐old woman with Ewing sarcoma involving the proximal humerus. (A) The plain radiograph shows a poorly defined osteolytic lesion. (B) Magnetic resonance imaging shows a lesion with low‐signal intensity on T1‐weighted imaging (top) and heterogeneous low‐ to high‐signal intensity T2‐weighted imaging (bottom). (C) Resection and joint replacement were performed. (D) Chest computed tomography reveals a nodular lesion in the right upper pulmonary lobe.

The patient's height was 156 cm and weight was 45 kg. She did not have a history of smoking or drinking alcohol. Results of laboratory testing were unremarkable, except for a slightly elevated serum C‐reactive protein level (0.83 mg/mL).

The patient underwent preoperative chemotherapy with vincristine, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, ifosfamide, and etoposide, followed by resection of the lesion that included surrounding normal tissue, and joint replacement (Fig. 1C). She then underwent chemotherapy consisting of total doses as follows: doxorubicin 375 mg/m2, cyclophosphamide 10,800 mg/m2, vincristine 1.8 mg/body, ifosfamide 72,000 mg/m2, and etoposide 4000 mg/m2. She maintained her weight, and her serum albumin level remained within the normal range throughout her treatment.

Routine computed tomography (CT) at the completion of chemotherapy detected a 5‐mm nodule in the patient's right upper pulmonary lobe (Fig. 1D), which had not been seen on the CT examination performed at the beginning of chemotherapy. In order to exclude multiple pulmonary metastases, a repeat CT examination performed 6 weeks after the completion of chemotherapy revealed only the solitary nodule.

Because Ewing sarcoma is frequently metastatic to the lung, the patient underwent resection of the solitary lung nodule based on a probable diagnosis of metastatic tumour. Examination of the resected lesion revealed pulmonary cryptococcosis due to Cryptococcus neoformans (Fig. 2). Lumbar puncture ruled out infection of the central nervous system. The patient was administered oral fluconazole (100 mg daily) for 18 weeks. No recurrence was seen during a 2‐year follow‐up period.

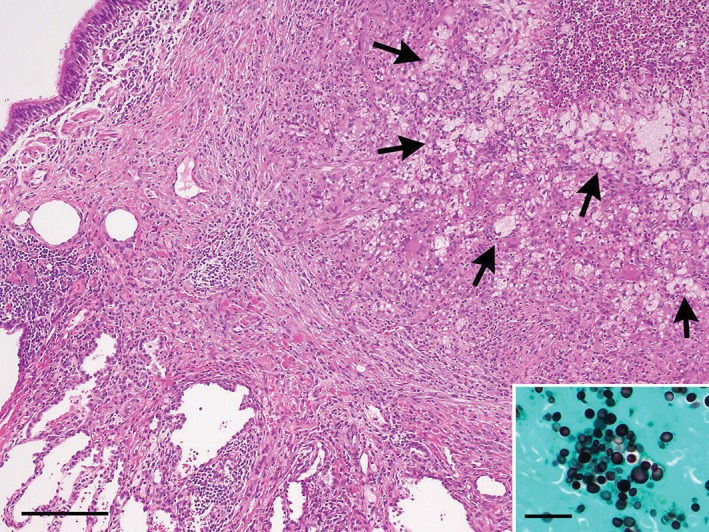

Figure 2.

Abscess‐forming granulomatous nodule due to cryptococcus infection in the lung (haematoxylin and eosin stain, bar = 200 µm). The nodular lesion contains many foamy or multivacuolated histiocytes (arrows) that are phagocytizing spherical fungi, which are highlighted by Grocott's methenamine silver staining (inset, bar = 20 µm).

Discussion

Computed tomography findings of pulmonary cryptococcosis have been reported to show a variety of features, including single or multiple nodules, or well‐defined consolidation. Nodular lesions of pulmonary cryptococcosis have a non‐specific appearance that is difficult to distinguish from metastatic lesions. [18F]‐2‐fluoro‐2‐deoxy‐D‐glucose positron emission tomography (FDG‐PET) shows a lesion with increased glucose metabolism; however, FDG accumulation cannot differentiate a nodule due to pulmonary cryptococcosis from a metastatic lesion 2. Because Ewing sarcoma has high metastasizing potential, a nodular pulmonary lesion that appears in a patient with high‐grade sarcoma, such as this patient, would be highly suspicious for metastatic sarcoma. Therefore, even if pulmonary cryptococcosis is in the differential diagnosis, resection of the pulmonary lesion is required in order to exclude metastatic Ewing sarcoma.

The treatment of pulmonary cryptococcosis depends on the immune status of the patient. Pulmonary cryptococcosis in the immunocompetent patient sometimes resolves spontaneously, without treatment 3. However, pulmonary cryptococcosis can spread to the central nervous system and cause life‐threatening meningitis 4. Therefore, oral fluconazole is recommended, especially for patients with high‐grade sarcoma.

Patients treated with cytotoxic chemotherapy for solid tumours had not been considered to be a group at risk for the development of pulmonary cryptococcosis. However, there was a single report of four children with sarcoma (two cases of Ewing sarcoma and two of rhabdomyosarcoma) who developed pulmonary cryptococcosis 5. These four pulmonary lesions were initially diagnosed as metastatic disease, and found to be pulmonary cryptococcosis after resection 5. All four children had undergone chemotherapy consisting of vincristine, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide, and three of them then underwent whole‐body radiation. The authors of that report assumed that the risk factors for development of pulmonary cryptococcosis in these patients were use of cyclophosphamide and whole‐body radiation 5.

Nodular pulmonary lesions seen in high‐grade sarcoma patients after they have undergone chemotherapy may be associated with pulmonary cryptococcosis. A definitive diagnosis requires excisional biopsy.

Disclosure Statements

No conflict of interest declared.

Appropriate written informed consent was obtained for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

Sakamoto A. and Hisaoka M. (2016) Pulmonary cryptococcosis mimicking a metastasis in a patient with Ewing sarcoma. Respirology Case Reports, 4 (5), e00181. doi: 10.1002/rcr2.181.

References

- 1. Brizendine KD, Baddley JW, and Pappas PG 2011. Pulmonary cryptococcosis. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 32:727–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Iwamoto Y 2007. Diagnosis and treatment of Ewing's sarcoma. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 37:79–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Khoury MB, Godwin JD, Ravin CE, et al. 1984. Thoracic cryptococcosis: immunologic competence and radiologic appearance. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 142:893–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Levitz SM 1991. The ecology of Cryptococcus neoformans and the epidemiology of cryptococcosis. Rev. Infect. Dis. 13:1163–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Allende M, Pizzo PA, Horowitz M, et al. 1993. Pulmonary cryptococcosis presenting as metastases in children with sarcomas. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 12:240–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]