Abstract

The cellular processes influenced by consuming polyunsaturated fatty acids remains poorly defined. Within skeletal muscle, a rate-limiting step in fatty acid oxidation is the movement of lipids across the sarcolemmal membrane, and therefore, we aimed to determine the effects of consuming flaxseed oil high in α-linolenic acid (ALA), on plasma membrane lipid composition and the capacity to transport palmitate. Rats fed a diet supplemented with ALA (10%) displayed marked increases in omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) within whole muscle and sarcolemmal membranes (approximately five-fold), at the apparent expense of arachidonic acid (−50%). These changes coincided with increased sarcolemmal palmitate transport rates (+20%), plasma membrane fatty acid translocase (FAT/CD36; +20%) abundance, skeletal muscle triacylglycerol content (approximately twofold), and rates of whole body fat oxidation (~50%). The redistribution of FAT/CD36 to the plasma membrane could not be explained by increased phosphorylation of signaling pathways implicated in regulating FAT/CD36 trafficking events (i.e., phosphorylation of ERK1/2, CaMKII, AMPK, and Akt), suggesting the increased n-3 PUFA composition of the plasma membrane influenced FAT/CD36 accumulation. Altogether, the present data provide evidence that a diet supplemented with ALA increases the transport of lipids into resting skeletal muscle in conjunction with increased sarcolemmal n-3 PUFA and FAT/CD36 contents.

Keywords: omega-3 fatty acids, membranes, lipids/oxidation, lipid transport, fatty acid translocase

within skeletal muscle, fatty acids have diverse biological functions, influencing membrane composition, gene transcription, enzymatic function, signal transduction, and oxidative metabolism (reviewed in Refs. 14 and 24). It is well established that skeletal muscle lipid composition is sensitive to dietary changes (3, 11, 37, 45, 46), raising the potential for nutritional interventions to influence skeletal muscle metabolic processes. As a result, in recent years, a focus has been placed on elucidating the consequences of dietary supplementation with omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (n-3 PUFAs). In particular, the biological effects of the essential fatty acid α-linolenic acid (ALA; 18:n3), or its desaturation products eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA; 20:5n3) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA; 20:6n3), are of interest because of their known reduction of risk factors associated with negative health outcomes (reviewed in Refs. 14 and 24).

Despite the potential for n-3 PUFAs to influence a variety of intracellular mechanisms within skeletal muscle, an understanding of the biological effects of these lipids at the molecular level remains limited. However, n-3 PUFAs are potent ligand activators of a class of transcription factors (21, 53), known as peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs), which have key roles in regulating the expression of a variety of genes involved in fatty acid metabolism [(49) and reviewed in Ref. 27]. As a result, n-3 PUFAs have been shown to increase the expression of PPAR targets, including nuclear respiratory factor, mitochondrial transcription factor A, carnitine palmitoyltransferase-I (CPT-I), and fatty acid translocase (FAT/CD36) (1, 25, 30, 51, 52). In addition to altering gene transcription, n-3 PUFAs have been shown to increase CPT-I activity, the rate-limiting enzyme in fatty acid oxidation, decrease CPT-I sensitivity to malonyl-CoA (M-CoA) inhibition (43), and improve submaximal ADP-stimulated respiration in the absence of the induction of mitochondrial biogenesis (19). Several studies have provided evidence that n-3 PUFA supplementation promotes fatty acid oxidation at rest and during exercise (10, 12, 13, 32), while in cultured muscle cells, n-3 provision improves fatty acid oxidation following exposure to a high-glucose environment (20). While an increase in whole body fat oxidation is not a universal finding (16, 39, 42), several organs influence whole body measurements, and together, with the known induction of fat oxidation genes in muscle, these data implicate skeletal muscle as a key tissue affected by n-3 supplementation. Combined, these data suggest n-3 PUFAs may alter fuel metabolism and promote fat oxidation through both PPAR-dependent and independent mechanisms.

To date, the biological effects of n-3 PUFAs have largely been attributed to improvements in mitochondrial bioenergetics (1, 25, 30, 51, 52); however, a key rate-limiting step in skeletal muscle fatty acid oxidation is the transport of lipids across the plasma membrane. Indeed, we have previously shown that without FAT/CD36, a primary fatty acid transport protein, skeletal muscle fat oxidation is not increased in the presence of mitochondrial biogenesis (36). The biological effects of n-3 PUFA supplementation on plasma membrane fatty acid transport have not been directly assessed; however, an increase in membrane fluidity could, in theory, increase the rate of lipid “flip-flop” through the phospholipid bilayer. Alternatively, n-3 supplementation has been suggested to alter lipid raft structure (44), a region of the plasma membrane where FAT/CD36 resides (41), which may promote FAT/CD36 retention/accumulation on the plasma membrane. In addition, recent evidence has implicated a rise in serum fatty acid concentration as a key mechanism involved in fatty acid transport protein redistribution to the plasma membrane (47), further suggesting that dietary lipid supplementation may promote sarcolemmal fatty acid transport. Although this possibility has not been investigated, n-3 feeding has been shown to alter the unsaturation of plasma membrane phospholipids, as well as the ability of insulin to bind to its plasma membrane receptor (31), supporting the assertion that membrane saturation influences the biological function of the phospholipid bilayer. In addition, cultured myotubes exposed to high n-3 PUFA concentrations display increased calculated lipid uptake rates (1). Although these measurements are influenced by intracellular metabolism, and therefore, are not an accurate assessment of transport, these data suggest n-3 supplementation can increase plasma membrane lipid transport. Therefore, we aimed to determine whether ALA supplementation, an n-3 PUFA that we have previously shown increases all n-3 PUFAs (including EPA and DHA) within muscle (35), would increase rates of plasma membrane palmitate transport in association with sarcolemmal FAT/CD36 accumulation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Five-week-old male Sprague-Dawley rats (n = 30 in total) were purchased from Charles River (St. Constant, Quebec, Canada). Animals were housed in a temperature-regulated room on a 12:12-h light-dark cycle with water available ad libitum. At 6 wk of age, animals were randomly assigned to consume a standard diet with or without ALA supplementation for 12 wk (animals were pair fed to maintain caloric intake). Both the control (no. AIN-93G; 20% protein, 64% carbohydrate, and 16% fat) and ALA-supplemented (no. AIN-93G + 10% flaxseed oil; 20% protein, 54% carbohydrate, and 26% fat) diets were purchased through Research Diets (New Brunswick, NJ), and the fatty acid composition of the diet was confirmed by gas chromatography, as previously reported (35). Thereafter, whole body indirect calorimetry was used to assess metabolism, and subsequently, animals were anesthetized after a 4-h fast (between 8 and 10 AM at the start of the dark cycle) with an injection of pentobarbital sodium (60 mg/kg), and muscles were excised for isolating mitochondria and whole muscle Western blot analysis (n = 7 per group) or for isolation of sarcolemmal membranes (n = 8 per group), as described below. Animal care and housing procedures were approved by the University of Guelph Animal Care Committee.

Characterization of basic blood profiles.

Whole blood was used to determine glucose concentrations (glucometer, Ascensia Elite XL; Bayer, Toronto, ON, Canada), while serum samples were used to measure nonesterified fatty acids (NEFA; Wako Chemicals, Richmond, VA) and glycerol concentrations (Sigma Aldrich, Oakville, ON, Canada), as specified by the manufacturer.

Skeletal muscle mitochondrial isolation and respiration.

Isolation of subsarcolemmal (SS) and intermyofibrillar (IMF) mitochondria was achieved by differential centrifugation from the red gastrocnemius muscle (n = 7 per group). This muscle contains ~25% of type I fibers, and very little type IIb fibers (4), similar to the fiber-type distribution of untrained human muscle (17). The respective speeds of centrifugation at each step were adapted from previous work (9), as well as the chemical composition of isolation buffer (50), as we have previously reported (28). Rates of mitochondrial oxygen consumption were performed in MiR05 respiration medium using an Oxygraph-2K (Oroboros Instruments, Innsbruck, Austria) at 25°C in room air saturation (28). State IV respiration was determined in the presence of 5 mM pyruvate and 2 mM malate. Thereafter, 100 μM of ADP was added to determine P/O ratios (ADP consumed per unit oxygen), followed by 5 mM ADP to determine maximal state III respiration, 10 mM glutamate to determine maximal complex I, and finally 10 mM succinate to determine maximal complex I+II respiration. Separate experiments were performed to measure rates of oxygen consumption in the presence of 25 μM palmitoyl-CoA (P-CoA), 2 mM malate, and 750 μM l-carnitine in the presence and absence of 100 μM ADP (P/O ratios), and 5 mM ADP (maximal respiration).

Isolation of giant sarcolemmal vesicles.

Following each of the treatments described above, giant sarcolemmal vesicles were prepared, as previously described (26). The red gastrocnemius and quadriceps muscles from a single animal were pooled to increase the protein recovery to enable palmitate transport and Western blot analysis to be performed from a single sample (n = 8 per group). Out of necessity, these were different animals than those used for isolating mitochondria and for whole muscle Western blot analyses. Briefly, muscles were cut into thin strips and incubated (1 h, 34°C, 100 rpm) in 140 mM KCl/10 mM MOPS (pH 7.4; BioShop) containing collagenase type VII (150 units/ml; Sigma) and aprotinin (10 mg/ml; BioShop). The muscle was washed with additional volumes of KCl/MOPS containing 10 mM Na2EDTA (pH 7.4; BioShop), and the supernatants were combined (7 ml total). Percoll (3.5%; GE Healthcare, Baie d’Urfé, QC, Canada), KCl (28 mM), and aprotinin (10 μg/ml) were added to the supernatant. This solution was layered under 3 ml of 4% Nycodenz (Sigma) and 1 ml KCl/MOPS, and centrifuged (60 g, 45 min, 25°C). The vesicles were harvested from the interface of Nycodenz and KCl/MOPS and were pelleted by centrifugation (9000 g, 5 min, 25°C), and the resulting pellet was resuspended in KCl/MOPS and immediately used for palmitate transport or stored at −80°C for Western blot analysis.

Palmitate transport.

Rates of palmitate transport into giant sarcolemmal vesicles were determined as previously reported (7, 22), using 0.3 μCi [3H]palmitate and 0.06 μCi [14C]mannitol. Briefly, isolated vesicles were added to a standard reaction buffer containing radiolabels and 15 μM palmitate and were incubated for 15 s. When the reaction terminated, the samples were immediately centrifuged, and radioactivity was determined in the pellet.

Western blot analysis.

Western blot analysis was performed on muscle homogenates from the red gastrocnemius muscle (n = 7 per group) and in isolated plasma membranes (n = 8 per group) using methods described previously (19). A BCA protein assay was performed, and constant protein (7 μg) was loaded for SDS-PAGE. Proteins were separated on a 7.5% resolving gel and transferred to PVDF membrane (Roche, Laval, QC, Canada). Membranes were blocked in 7.5% BSA in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween-20 (TBS-T) for 1 h at room temperature. Membranes were incubated in primary antibody diluted in blocking solution overnight at 4°C. After three washes in TBS-T, membranes were incubated in the appropriate HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), detected using enhanced chemiluminescence (Perkin Elmer) and quantified by densitometry (Alpha Innotech Fluorchem HD2, Fisher Scientific). The anti-FAT/CD36 antibody was a gift from N. N. Tandon (Otsuka Maryland Medicinal Laboratories), the anti-FABPpm was a gift from J. Calles-Escandon (Wake Forest University), and the anti-MCT-1 was a gift from H. Hatta (Tokyo University). The following commercially available antibodies were used: anti-PDH subunit E1α (cat. no. A-21323; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), OXPHOS (cat. no. ab110413; Abcam, Cambridge, MA), COX-IV (cat. number MA5–15078aka CIV–IV, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), α-tubulin (cat. no. ab7291; Abcam), FATP4 (cat. no. sc-5835; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). In addition, total (cat. no. 4436) and phosphorylated calcium calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII Thr-286, cat. no. 3361), AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK Thr-172, cat. no. 2531; total, cat. no. 2532), ERK1/2 (cat. no. 9101; total, cat. no. 9102), and PKB (Akt Ser-473, cat. no. 9271; total, cat. no. 2964) were all purchased from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA). All samples for a given target were transferred onto a single membrane to limit variation. MCT-1 and α-tubulin were used to confirm constant loading for plasma membrane and muscle homogenates, respectively. These proteins were not different following ALA supplementation, and therefore, absolute values are reported.

Analysis of sarcolemmal PUFA content.

Lipids were analyzed in isolated sarcolemmal vesicles and whole muscle by gas chromatography, as previously described (15, 35). The retention times of standards and individual fatty acids were quantified and expressed as a percentage of control animals, similar to what we have previously reported in isolated mitochondrial membranes (19). The effect of ALA supplementation on the sarcolemmal lipid composition could only be performed on a few of the giant sarcolemmal vesicles with sufficient protein remaining after transport rates and Western blot analysis were performed (n = 3), while whole muscle measurements were performed on a larger data set (n = 7).

Resting whole body metabolic measurements.

After the 12-wk dietary intervention, animals were placed in metabolic cages (Columbus Instruments, Columbus, OH) at 8 AM at the start of their normal light cycle. Resting oxygen consumption (V̇o2) and carbon dioxide production (V̇co2) were recorded continuously; however, to ensure animals were acclimatized to the metabolic cages and to ensure that transition periods between light and dark cycles were not included, data were only analyzed over 6 h in the middle of the dark and light cycles (1030–0430). V̇o2 and V̇co2 values were used to calculate total carbohydrate and fat oxidation, and energy expenditure as follows (40): CHO oxidation = 4.585 V̇co2 production (l/min) − 3.226 V̇o2 production (l/min); and fat oxidation = 1.695 V̇o2 production (l/min) − 1.701 V̇co2 production (l/min).

Values were divided by 60 and multiplied by 16.19 (CHO) and 40.80 (fat) to convert to kilojoules per hour.

Statistics.

A two-tailed unpaired Student's t-test was used to examine all data, with the exception of whole body metabolism, which was analyzed using a two-way ANOVA, followed by a Tukey post hoc analysis where appropriate. Although the plasma membrane lipid analysis is reported as a percentage of the control diet, the absolute values were used for statistical analysis. A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant, and values are reported as means ± SE.

RESULTS

Basic characterization of animals.

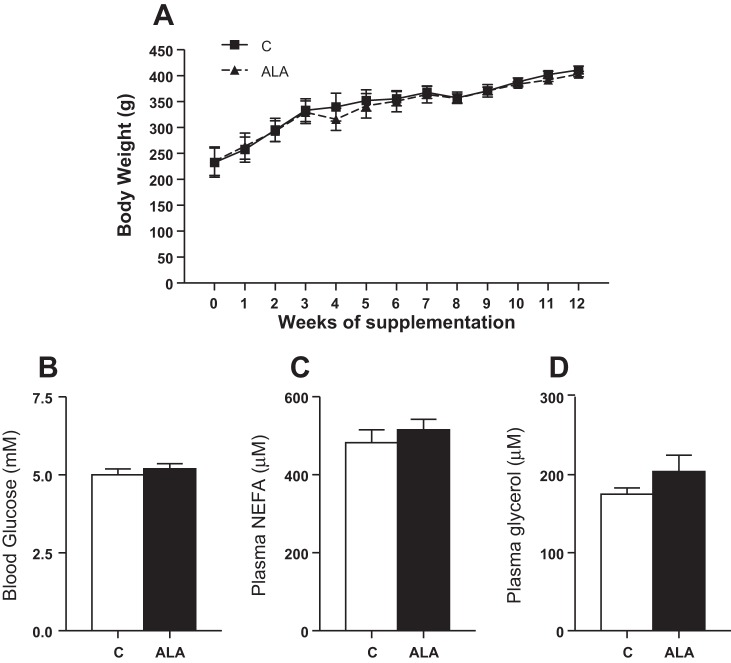

Given the additional fat content in the ALA diet, animals supplemented with ALA were pair fed to ad libitum control-fed animals to minimize variances in caloric consumption. This approach normalized weight gain between the two groups, as body weight was not different at any time point (Fig. 1A). In addition, ALA supplementation did not alter blood glucose, serum NEFA, or glycerol concentrations (Fig. 1, B–D).

Fig. 1.

Body weight (A) and basic blood characterization of animals following α-linolenic acid (ALA) supplementation. Blood glucose (B), nonesterified fatty acids (NEFA; C), and glycerol (D) concentrations are reported. Values are reported as means ± SE; n = 15 for each measurement, as values represent all animals in the study, including those used for isolated mitochondrial (n = 7) and plasma membrane (n = 8) assessments.

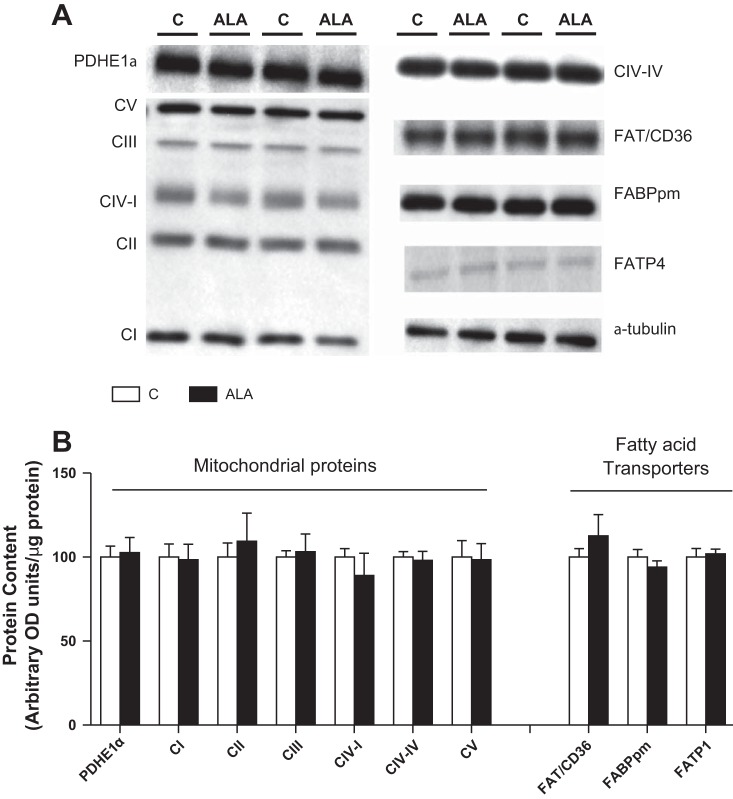

Effects of ALA on mitochondrial bioenergetics and protein content of PPAR targets.

We first evaluated the effect of ALA supplementation on indices of mitochondrial bioenergetics. In isolated SS and IMF mitochondria ALA consumption did not alter respiration or coupling efficiency in the presence of various substrates, including palmitoyl-CoA (P-CoA: Table 1). In addition, ALA supplementation did alter the accumulation of various mitochondrial proteins or the total cellular content of fatty acid transport proteins (Fig. 2, A and B). Combined, these data suggest a lack of ALA-induced changes in mitochondrial oxidative capacity or accumulation of fatty acid transport proteins.

Table 1.

Mitochondrial respiratory measures

| SS Mitochondria |

IMF Mitochondria |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | ALA | Control | ALA | |

| Pyruvate protocol | ||||

| State 4 | 24 ± 3 | 21 ± 2 | 30 ± 7 | 33 ± 6 |

| State 3 | 239 ± 21 | 196 ± 14 | 372 ± 60 | 397 ± 49 |

| Max complex 1 | 368 ± 36 | 291 ± 30 | 559 ± 77 | 640 ± 51 |

| Max complex 1 + 2 | 440 ± 44 | 346 ± 36 | 658 ± 87 | 731 ± 56 |

| RCR | 11.2 ± 1.8 | 9.6 ± 1.0 | 14.9 ± 2.8 | 15.1 ± 3.7 |

| P/O | 2.5 ± 0.1 | 2.6 ± 0.1 | 2.5 ± 0.1 | 2.5 ± 0.1 |

| P-CoA protocol | ||||

| State 4 | 16 ± 16 | 17 ± 2 | 30 ± 9 | 37 ± 9 |

| State 3 | 132 ± 14 | 104 ± 18 | 272 ± 88 | 276 ± 27 |

| RCR | 7.0 ± 0.7 | 7.1 ± 0.6 | 7.6 ± 0.5 | 8.3 ± 1.7 |

| P/O | 2.2 ± 0.1 | 2.4 ± 0.1 | 2.6 ± 0.2 | 2.2 ± 0.1 |

Absolute rates of oxygen consumption in the presence (state 3) and absence (state 4) of ADP in isolated subsarcolemmal (SS) and intermyofibrillar (IMF) mitochondria following the consumption of a control diet or a diet supplemented with α-linolenic acid (ALA). State 3 and 4 values are expressed as nmol·min−1·mg−1 mitochondrial protein. Respiratory control ratio (RCR) and ADP consumed per unit oxygen (P/O ratio) reflect mitochondrial integrity and coupling. Data are presented as means ± SE; n = 7. P-CoA; palmitoyl-CoA.

Fig. 2.

The effect of ALA on the skeletal muscle content of mitochondrial proteins and fatty acid transporters. Representative blots are shown in A, while quantified data (expressed as means ± SE) are reported in B. n = 8 for each measure, and “C” specifies control diet.

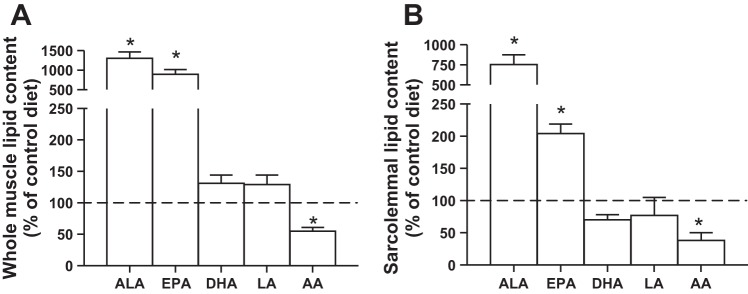

Effects of ALA on whole muscle and plasma membrane lipid composition.

Given the lack of change in mitochondrial proteins, we next determined ALA PUFA content in muscle to ensure the diet had the expected response in accumulating ALA within muscle. The consumption of an ALA-fortified diet increased the skeletal muscle content of ALA ~10-fold, while also increasing EPA content approximately eight-fold (Fig. 3A). These changes appeared to be partially at the expense of AA, which decreased its content ~50% (Fig. 3A). We also evaluated the effect of ALA supplementation on the lipid composition of the plasma membrane. The basic pattern of the whole muscle was replicated in a small subset of plasma membrane samples (n = 3) with sufficient protein to determine the lipid composition following functional analysis and Western blotting (data found below), as ALA and EPA both increased (approximately two- to eight-fold), while AA decreased around 50% (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

The effect of ALA on the lipid composition of muscle. Values are reported for ALA, eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), linoleic acid (LA), and arachidonic acid (AA) in whole muscle (A) and in isolated sarcolemmal vesicles (B). Values are represented as means ± SE, expressed as a percentage of control (dotted line). n = 8 for whole muscle, and n = 3 for sarcolemmal vesicles. *Significantly different compared with the control diet, P < 0.05.

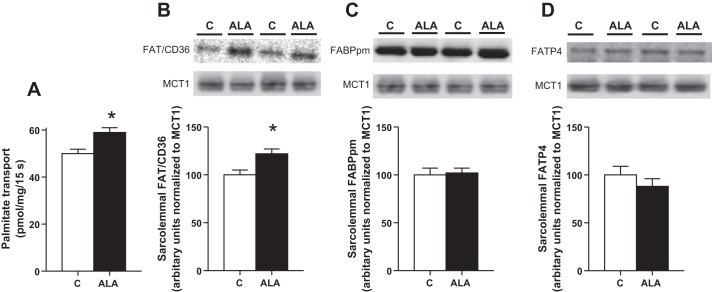

Effects of ALA on plasma membrane palmitate transport.

We next evaluated the effects of ALA consumption on plasma membrane fatty acid transport rates and fatty acid transport protein content in sarcolemmal vesicles. Ingestion of the ALA diet increased the rate of sarcolemmal palmitate transport ~20% (Fig. 4A), and similarly, it increased sarcolemmal FAT/CD36 protein content ~20% (Fig. 4B) without altering FABPpm or FATP4 contents (Fig. 4, C and D).

Fig. 4.

The effect of ALA on plasma membrane palmitate transport (A) and fatty acid transport protein content. Sarcolemmal FAT/CD36 (B), FABPpm (C), and FATP4 (D) representative blots and quantified values are shown. Values are reported as means ± SE; n = 8 for each measure. *Significantly different compared with the control diet, P < 0.05.

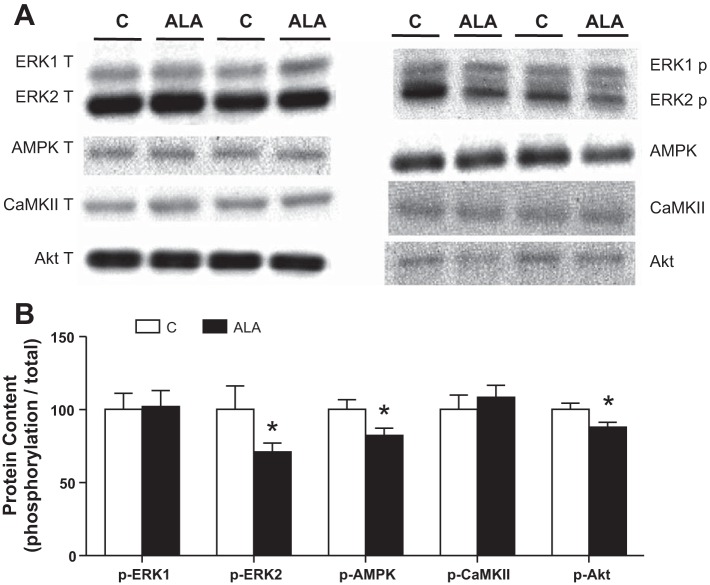

Potential intracellular signals influencing ALA-mediated accumulation of plasma membrane FAT/CD36.

Several signaling cascades have been implicated in causing FAT/CD36 redistribution to the plasma membrane. Therefore, we determined the phosphorylation status of ERK1/2, AMPK (Thr-172), CaMKII (Thr-286), and Akt (Ser-473). However, none of these signaling molecules displayed increased phosphorylation, and several actually displayed minor attenuations (Fig. 5, A and B), and, therefore, cannot explain the observed increase in sarcolemmal FAT/CD36 accumulation.

Fig. 5.

The effect of ALA on intramuscular signaling implicated in FAT/CD36 trafficking events. Values are reported for extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase (ERK1/2), AMPK (Thr-172), calcium calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII Thr-286) and protein kinase B (Akt Ser-473). Representative blots (A) and quantified values (B) are expressed as means ± SE; n = 8. *Significantly different compared with the control diet, P < 0.05.

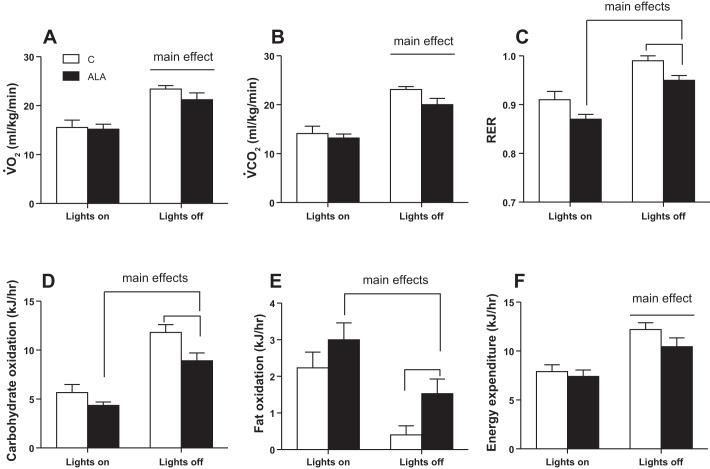

Effects of ALA on whole body metabolism.

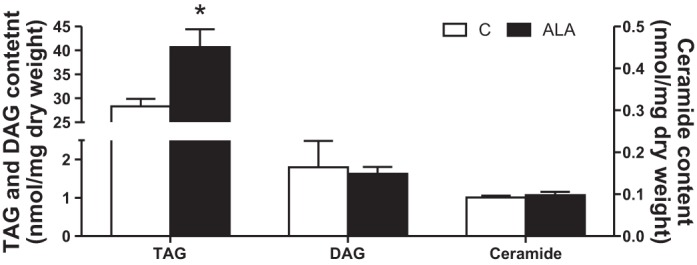

Given the increase in plasma membrane lipid transport and accumulation of intramuscular lipids, we determined whether ALA supplementation altered whole body metabolism, as ascertained by indirect calorimetry. V̇o2, V̇co2, and energy expenditure were higher when rats were awake (lights off); however, these parameters were not altered following ALA consumption (Figs. 6 and 7, A, B, and F). In contrast, the RER was lower (P < 0.05) in ALA-treated rats (Fig. 7C), and as a result, these rats displayed a reduction in carbohydrate oxidation (Fig. 7D) and a ~50% increase in fat oxidation (Fig. 7E).

Fig. 6.

The effect of ALA on intramuscular triacylglycerol (TAG), diacylglycerol (DAG), and ceramide contents. Values are presented as means ± SE, expressed as a percentage of lean control (dotted line). n = 7 for each measure. *Significantly different compared with the control diet, P < 0.05.

Fig. 7.

The effect of ALA on whole-body metabolism. Values over a 6-h period in the light and dark cycles are shown for oxygen consumption (V̇o2; A), carbon dioxide production (V̇co2; B), respiratory exchange ratio (RER; C) and calculated rates of carbohydrate (D) and fat (E) oxidation, as well as total energy expenditure (F). Values are expressed as means ± SE; n = 8 for each measure. Main effects are depicted with lines.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we provide evidence that the consumption of an ALA-supplemented diet for 12 wk increases 1) the n-3 PUFA content of the plasma membrane, 2) FAT/CD36 accumulation on the plasma membrane, 3) sarcolemmal fatty acid transport rates, 4) intramuscular triacylglycerol, and 5) whole body fat oxidation. These responses occur in the absence of changes in mitochondrial content and maximal respiratory function. Combined, these data implicate an increase in plasma membrane palmitate transport as a fundamental process influenced by ALA dietary interventions.

Dietary PUFAs and mitochondrial bioenergetics.

Dietary supplementation with n-3 PUFAs has been suggested to induce PPAR-mediated gene transcription and mitochondrial biogenesis (1, 25, 30, 51, 52). However, in the present study, consumption of ALA did not alter the content of several mitochondrial proteins, nor did it influence indices of bioenergetics in isolated mitochondria. While this appears at odds with previous literature from cell culture experiments (1, 51, 52), we did not measure mRNA expression of FAT/CD36, as previously reported, but rather FAT/CD36 protein, and there are several processes that can influence protein accumulation beyond gene transcription. In addition, the lack of changes in the protein content of PPAR targets in the present study is supported by previous work in high-fat fed and obese Zucker rats (30, 34). However, we have previously shown in humans that EPA/DHA supplementation increases n-3 incorporation into mitochondrial membranes and improves the apparent mitochondrial sensitivity to ADP in permeabilized muscle fibers (19). This response, in theory, could promote fat oxidation by decreasing cytosolic free ADP concentrations and allosteric activation of rate-limiting enzymes in carbohydrate oxidation, namely, phosphorylase and pyruvate dehydrogenase (48); however, this remains to be established. Regardless of the potential to alter mitochondrial bioenergetics, we have previously shown that an upregulation of plasma membrane fatty acid transport is required to utilize a potential improvement in mitochondrial lipid metabolism (36), emphasizing the importance of the observed increase in sarcolemmal palmitate transport in the current study.

Dietary PUFAs and sarcolemmal lipid transport: potential mechanisms for the observed increase in FAT/CD36 content.

An increase in sarcolemmal PUFA composition has previously been shown to affect insulin-mediated glucose transport rates into skeletal muscle (1). The present data extend these findings to lipid metabolism, by showing that the accumulation of PUFAs, specifically ALA and EPA, in the plasma membrane occurs in conjunction with an increased rate of palmitate transport. It is unclear from the current data whether the increase in lipid transport is a direct result of changes in membrane composition or whether it can be attributed to the accumulation of FAT/CD36. However, sarcolemmal FAT/CD36 is considered a key fatty acid transport protein, as knockout mice have impaired lipid transport capacities and reduced whole body fat oxidation rates (5, 36), while, conversely, overexpression of FAT/CD36 increases skeletal muscle lipid oxidation (38). Therefore, the accumulation of FAT/CD36 on the plasma membrane likely contributes to the observed increased transport rate, a supposition supported by the proportional change in both sarcolemmal transport and FAT/CD36 content. However, considering the simultaneous changes in membrane PUFA composition and FAT/CD36 content, future work using n-3 PUFA dietary interventions in FAT/CD36-null mice are required to delineate the independent influence of altering membrane lipid composition on fatty acid transport rates.

In the present study, the accumulation of FAT/CD36 on the plasma membrane occurred in the absence of alterations in total cellular protein FAT/CD36 content, suggesting a stable redistribution of FAT/CD36 to the cell surface. Several signaling pathways have been implicated in regulating FAT/CD36 subcellular location in muscle. For instance, the pharmacological inhibition of ERK1/2 with PD-98059 prevents exercise-induced translocation of FAT/CD36 to the plasma membrane, 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide-mediated activation of AMPK induces FAT/CD36 sarcolemmal translocation in skeletal muscle and in cardiac myocytes (5, 23, 33), CaMKII signaling temporally aligns with FAT/CD36 translocation during muscle contraction (23), and insulin rapidly induces FAT/CD36 accumulation on the plasma membrane (47). However, our knowledge of the intracellular mechanisms influencing FAT/CD36 location is clearly incomplete, as exercise-induced translocation of FAT/CD36 to the plasma membrane is retained in AMPKα2 kinase dead (KD) mice (23) and ERK phosphorylation occurs after the induction of FAT/CD36 trafficking (23). In addition, the classical role of insulin in mediating postprandial FAT/CD36 trafficking has recently been challenged, as fatty acids themselves have been proposed to mediate FAT/CD36 subcellular location through an unknown mechanism (47). In the present study, none of the previously implicated pathways appeared to be activated at the end of the study. It remains unknown whether these signaling events were activated earlier in the feeding intervention and contributed to the initial induction of FAT/CD36 redistribution. Regardless, the activation of known signaling pathways cannot explain the observed accumulation of FAT/CD36 on sarcolemmal membranes.

While the cause of the observed FAT/CD36 redistribution remains unknown, DHA supplementation has been shown to decrease SERCA-mediated calcium transport efficiency, and a rise in cytosolic calcium has been shown to induce FAT/CD36 translocation to the plasma membrane in the absence of CaMKII activation (29), which was also not activated in the present study. It remains possible that a rise in cytosolic calcium could induce other nontraditional signaling events to influence FAT/CD36 translocation. Alternatively, as opposed to ALA activating intracellular mechanisms that affect Rab-GAP GTPase activity and vesicular movement toward the plasma membrane, the observed increase in ALA/EPA content within the sarcolemma could influence vesicular merging/endocytosis events to account for the detected FAT/CD36 retention. Regardless of these knowledge gaps, the present study provides evidence that ALA supplementation increases the rate of lipid transport across the plasma membrane of skeletal muscle.

Perspectives and Significance

The increased rate of lipid transport, in the absence of a change in energy expenditure, likely contributes to the observed increase in intramuscular lipid content and rates of whole body fat oxidation in the present study. In contrast, a recent paper has shown that EPA/DHA feeding in humans has a variable effect on whole body metabolism, and as a result the observed 30% increase in some fatty acid transport proteins was not statistically different (16). The direct translation to human muscle, therefore, awaits further experiments. Moreover, while n-3 PUFAs are generally considered to positively impact health and insulin sensitivity (reviewed in Refs. 14 and 24), an increase in lipid transport has been linked to the development of skeletal muscle insulin resistance (2, 6, 8), and therefore, ALA may not be positive in all situations. However, we have recently shown that ALA supplementation in healthy rats does not augment indices of insulin sensitivity in skeletal muscle (30, 34). Although it is tempting to speculate that ALA supplementation, and the associated increase in plasma membrane lipid transport, may exacerbate ectopic lipid accumulation in the presence of a high-fat and/or high-caloric diet, we have also recently shown that ALA supplementation improves skeletal muscle insulin sensitivity in the absence of changes in intramuscular lipid profiles (35). Therefore, in contrast to the present data, in obese Zucker rats, ALA supplementation does not increase intramuscular TAG content (35). The skeletal muscle of obese Zucker rats is resistant to the induction of FAT/CD36 translocation (18), which may explain this discrepancy. Alternatively, it remains to be determined whether ALA feeding similarly alters the membrane lipid composition or plasma membrane biology in obese animals.

Unfortunately, it remains unknown what induces FAT/CD36 accumulation on the plasma membrane following ALA consumption, as none of the signaling proteins studied were increased. However, it should be acknowledged in the present study that the ALA diet contained a higher proportion of fat, and therefore, on average, these animals consumed ~0.6 g of additional fat per day. This dietary approach was utilized as it is easier to supplement a human diet than to replace macronutrients; however, the additional fat may contribute to the responses observed as we have recently provided evidence that lipids induce fatty acid transport protein trafficking events in a feed-forward manner (47). Therefore, we cannot rule out the possibility that the increased composition of lipids in the ALA-fortified diet caused the observed responses. Future research should consider replacing lipids with n-3 PUFAs, as opposed to supplementing diets to better ascertain the mechanisms behind the observed responses. Regardless, the present data show that a diet supplemented with ALA increases the transport of lipids into resting skeletal muscle in association with an increase in sarcolemmal FAT/CD36 content. Although we cannot explain why this occurred, we have provided evidence that activation of ERK, AMPK, CaMKII, and Akt signaling are not responsible.

GRANTS

This work was funded by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, and infrastructure was purchased with the assistance of the Canadian Foundation for Innovation, as well as the Ontario Research Fund.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Z.C., P.-A.B., L.C., D.C.W., A.C., and G.P.H. performed experiments; Z.C., P.-A.B., L.C., D.C.W., A.C., and G.P.H. analyzed data; Z.C., P.-A.B., L.C., D.C.W., A.C., and G.P.H. interpreted results of experiments; Z.C., P.-A.B., and G.P.H. prepared figures; Z.C., P.-A.B., L.C., D.C.W., and A.C. edited and revised manuscript; Z.C., P.-A.B., L.C., D.C.W., A.C., and G.P.H. approved final version of manuscript; G.P.H. conception and design of research; G.P.H. drafted manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aas V, Rokling-Andersen MH, Kase ET, Thoresen GH, Rustan AC. Eicosapentaenoic acid (20:5 n-3) increases fatty acid and glucose uptake in cultured human skeletal muscle cells. J Lipid Res 47: 366–374, 2006. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M500300-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aguer C, Mercier J, Man CYW, Metz L, Bordenave S, Lambert K, Jean E, Lantier L, Bounoua L, Brun JF, Raynaud de Mauverger E, Andreelli F, Foretz M, Kitzmann M. Intramyocellular lipid accumulation is associated with permanent relocation ex vivo and in vitro of fatty acid translocase (FAT)/CD36 in obese patients. Diabetologia 53: 1151–1163, 2010. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-1708-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersson A, Nälsén C, Tengblad S, Vessby B. Fatty acid composition of skeletal muscle reflects dietary fat composition in humans. Am J Clin Nutr 76: 1222–1229, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benton CR, Nickerson JG, Lally J, Han XX, Holloway GP, Glatz JF, Luiken JJ, Graham TE, Heikkila JJ, Bonen A. Modest PGC-1α overexpression in muscle in vivo is sufficient to increase insulin sensitivity and palmitate oxidation in subsarcolemmal, not intermyofibrillar, mitochondria. J Biol Chem 283: 4228–4240, 2008. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704332200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonen A, Han XX, Habets DD, Febbraio M, Glatz JF, Luiken JJ. A null mutation in skeletal muscle FAT/CD36 reveals its essential role in insulin- and AICAR-stimulated fatty acid metabolism. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 292: E1740–E1749, 2007. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00579.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonen A, Jain SS, Snook LA, Han XX, Yoshida Y, Buddo KH, Lally JS, Pask ED, Paglialunga S, Beaudoin MS, Glatz JF, Luiken JJ, Harasim E, Wright DC, Chabowski A, Holloway GP. Extremely rapid increase in fatty acid transport and intramyocellular lipid accumulation but markedly delayed insulin resistance after high fat feeding in rats. Diabetologia 58: 2381–2391, 2015. doi: 10.1007/s00125-015-3691-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonen A, Luiken JJ, Liu S, Dyck DJ, Kiens B, Kristiansen S, Turcotte LP, Van Der Vusse GJ, Glatz JF. Palmitate transport and fatty acid transporters in red and white muscles. Am J Physiol 275: E471–E478, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bonen A, Parolin ML, Steinberg GR, Calles-Escandon J, Tandon NN, Glatz JF, Luiken JJ, Heigenhauser GJ, Dyck DJ. Triacylglycerol accumulation in human obesity and type 2 diabetes is associated with increased rates of skeletal muscle fatty acid transport and increased sarcolemmal FAT/CD36. FASEB J 18: 1144–1146, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cogswell AM, Stevens RJ, Hood DA. Properties of skeletal muscle mitochondria isolated from subsarcolemmal and intermyofibrillar regions. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 264: C383–C389, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Couet C, Delarue J, Ritz P, Antoine JM, Lamisse F. Effect of dietary fish oil on body fat mass and basal fat oxidation in healthy adults. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 21: 637–643, 1997. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dangardt F, Chen Y, Gronowitz E, Dahlgren J, Friberg P, Strandvik B. High physiological omega-3 fatty acid supplementation affects muscle fatty acid composition and glucose and insulin homeostasis in obese adolescents. J Nutr Metab 2012: 395757, 2012. doi: 10.1155/2012/395757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delarue J, Labarthe F, Cohen R. Fish-oil supplementation reduces stimulation of plasma glucose fluxes during exercise in untrained males. Br J Nutr 90: 777–786, 2003. doi: 10.1079/BJN2003964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Delarue J, Li CH, Cohen R, Corporeau C, Simon B. Interaction of fish oil and a glucocorticoid on metabolic responses to an oral glucose load in healthy human subjects. Br J Nutr 95: 267–272, 2006. doi: 10.1079/BJN20051631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Endo J, Arita M. Cardioprotective mechanism of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. J Cardiol 67: 22–27, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2015.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Folch J, Lees M, Sloane Stanley GH. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J Biol Chem 226: 497–509, 1957. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gerling CJ, Whitfield J, Mukai K, Spriet LL. Variable effects of 12 weeks of omega-3 supplementation on resting skeletal muscle metabolism. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 39: 1083–1091, 2014. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2014-0049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gollnick PD, Armstrong RB, Saltin B, Saubert CW IV, Sembrowich WL, Shepherd RE. Effect of training on enzyme activity and fiber composition of human skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol 34: 107–111, 1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Han XX, Chabowski A, Tandon NN, Calles-Escandon J, Glatz JF, Luiken JJ, Bonen A. Metabolic challenges reveal impaired fatty acid metabolism and translocation of FAT/CD36 but not FABPpm in obese Zucker rat muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 293: E566–E575, 2007. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00106.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herbst EA, Paglialunga S, Gerling C, Whitfield J, Mukai K, Chabowski A, Heigenhauser GJ, Spriet LL, Holloway GP. Omega-3 supplementation alters mitochondrial membrane composition and respiration kinetics in human skeletal muscle. J Physiol 592: 1341–1352, 2014. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.267336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hessvik NP, Bakke SS, Fredriksson K, Boekschoten MV, Fjørkenstad A, Koster G, Hesselink MK, Kersten S, Kase ET, Rustan AC, Thoresen GH. Metabolic switching of human myotubes is improved by n-3 fatty acids. J Lipid Res 51: 2090–2104, 2010. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M003319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Itoh T, Fairall L, Amin K, Inaba Y, Szanto A, Balint BL, Nagy L, Yamamoto K, Schwabe JW. Structural basis for the activation of PPARγ by oxidized fatty acids. Nat Struct Mol Biol 15: 924–931, 2008. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jain SS, Luiken JJ, Snook LA, Han XX, Holloway GP, Glatz JF, Bonen A. Fatty acid transport and transporters in muscle are critically regulated by Akt2. FEBS Lett 589, 19 Pt B: 2769–2775, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2015.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jeppesen J, Albers PH, Rose AJ, Birk JB, Schjerling P, Dzamko N, Steinberg GR, Kiens B. Contraction-induced skeletal muscle FAT/CD36 trafficking and FA uptake is AMPK independent. J Lipid Res 52: 699–711, 2011. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M007138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jeromson S, Gallagher IJ, Galloway SD, Hamilton DL. Omega-3 fatty acids and skeletal muscle health. Mar Drugs 13: 6977–7004, 2015. doi: 10.3390/md13116977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson ML, Lalia AZ, Dasari S, Pallauf M, Fitch M, Hellerstein MK, Lanza IR. Eicosapentaenoic acid but not docosahexaenoic acid restores skeletal muscle mitochondrial oxidative capacity in old mice. Aging Cell 14: 734–743, 2015. doi: 10.1111/acel.12352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Juel C. Muscle lactate transport studied in sarcolemmal giant vesicles. Biochim Biophys Acta 1065: 15–20, 1991. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(91)90004-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kota BP, Huang TH, Roufogalis BD. An overview on biological mechanisms of PPARs. Pharmacol Res 51: 85–94, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2004.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lally JS, Herbst EA, Matravadia S, Maher AC, Perry CG, Ventura-Clapier R, Holloway GP. Over-expressing mitofusin-2 in healthy mature mammalian skeletal muscle does not alter mitochondrial bioenergetics. PLoS One 8: e55660, 2013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lally JS, Jain SS, Han XX, Snook LA, Glatz JF, Luiken JJ, McFarlan J, Holloway GP, Bonen A. Caffeine-stimulated fatty acid oxidation is blunted in CD36 null mice. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 205: 71–81, 2012. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2011.02396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lanza IR, Blachnio-Zabielska A, Johnson ML, Schimke JM, Jakaitis DR, Lebrasseur NK, Jensen MD, Sreekumaran Nair K, Zabielski P. Influence of fish oil on skeletal muscle mitochondrial energetics and lipid metabolites during high-fat diet. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 304: E1391–E1403, 2013. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00584.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu S, Baracos VE, Quinney HA, Clandinin MT. Dietary omega-3 and polyunsaturated fatty acids modify fatty acyl composition and insulin binding in skeletal-muscle sarcolemma. Biochem J 299: 831–837, 1994. doi: 10.1042/bj2990831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Logan SL, Spriet LL. Omega-3 fatty acid supplementation for 12 weeks increases resting and exercise metabolic rate in healthy community-dwelling older females. PLoS One 10: e0144828, 2015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0144828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luiken JJ, Coort SL, Willems J, Coumans WA, Bonen A, van der Vusse GJ, Glatz JF. Contraction-induced fatty acid translocase/CD36 translocation in rat cardiac myocytes is mediated through AMP-activated protein kinase signaling. Diabetes 52: 1627–1634, 2003. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.7.1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matravadia S, Herbst EA, Jain SS, Mutch DM, Holloway GP. Both linoleic and α-linolenic acid prevent insulin resistance but have divergent impacts on skeletal muscle mitochondrial bioenergetics in obese Zucker rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 307: E102–E114, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00032.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matravadia S, Zabielski P, Chabowski A, Mutch DM, Holloway GP. LA and ALA prevent glucose intolerance in obese male rats without reducing reactive lipid content, but cause tissue-specific changes in fatty acid composition. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 310: R619–R630, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00297.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McFarlan JT, Yoshida Y, Jain SS, Han XX, Snook LA, Lally J, Smith BK, Glatz JF, Luiken JJ, Sayer RA, Tupling AR, Chabowski A, Holloway GP, Bonen A. In vivo, fatty acid translocase (CD36) critically regulates skeletal muscle fuel selection, exercise performance, and training-induced adaptation of fatty acid oxidation. J Biol Chem 287: 23502–23516, 2012. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.315358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McGlory C, Galloway SD, Hamilton DL, McClintock C, Breen L, Dick JR, Bell JG, Tipton KD. Temporal changes in human skeletal muscle and blood lipid composition with fish oil supplementation. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 90: 199–206, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2014.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nickerson JG, Alkhateeb H, Benton CR, Lally J, Nickerson J, Han XX, Wilson MH, Jain SS, Snook LA, Glatz JF, Chabowski A, Luiken JJ, Bonen A. Greater transport efficiencies of the membrane fatty acid transporters FAT/CD36 and FATP4 compared with FABPpm and FATP1 and differential effects on fatty acid esterification and oxidation in rat skeletal muscle. J Biol Chem 284: 16,522–16,530, 2009. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.004788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Noreen EE, Sass MJ, Crowe ML, Pabon VA, Brandauer J, Averill LK. Effects of supplemental fish oil on resting metabolic rate, body composition, and salivary cortisol in healthy adults. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 7: 31, 2010. doi: 10.1186/1550-2783-7-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Péronnet F, Massicotte D. Table of nonprotein respiratory quotient: an update. Can J Sport Sci 16: 23–29, 1991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pohl J, Ring A, Korkmaz U, Ehehalt R, Stremmel W. FAT/CD36-mediated long-chain fatty acid uptake in adipocytes requires plasma membrane rafts. Mol Biol Cell 16: 24–31, 2005. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-07-0616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Poprzecki S, Zajac A, Chalimoniuk M, Waskiewicz Z, Langfort J. Modification of blood antioxidant status and lipid profile in response to high-intensity endurance exercise after low doses of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids supplementation in healthy volunteers. Int J Food Sci Nutr 60, Suppl 2: 67–79, 2009. doi: 10.1080/09637480802406161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Power GW, Newsholme EA. Dietary fatty acids influence the activity and metabolic control of mitochondrial carnitine palmitoyltransferase I in rat heart and skeletal muscle. J Nutr 127: 2142–2150, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shaikh SR. Biophysical and biochemical mechanisms by which dietary N-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids from fish oil disrupt membrane lipid rafts. J Nutr Biochem 23: 101–105, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2011.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith GI, Atherton P, Reeds DN, Mohammed BS, Rankin D, Rennie MJ, Mittendorfer B. Dietary omega-3 fatty acid supplementation increases the rate of muscle protein synthesis in older adults: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr 93: 402–412, 2011. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.005611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smith GI, Atherton P, Reeds DN, Mohammed BS, Rankin D, Rennie MJ, Mittendorfer B. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids augment the muscle protein anabolic response to hyperinsulinaemia-hyperaminoacidaemia in healthy young and middle-aged men and women. Clin Sci (Lond) 121: 267–278, 2011. doi: 10.1042/CS20100597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Snook LA, Wright DC, Holloway GP. Postprandial control of fatty acid transport proteins’ subcellular location is not dependent on insulin. FEBS Lett 590: 2661–2670, 2016. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.12260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Spriet LL, Watt MJ. Regulatory mechanisms in the interaction between carbohydrate and lipid oxidation during exercise. Acta Physiol Scand 178: 443–452, 2003. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201X.2003.01152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tanaka T, Yamamoto J, Iwasaki S, Asaba H, Hamura H, Ikeda Y, Watanabe M, Magoori K, Ioka RX, Tachibana K, Watanabe Y, Uchiyama Y, Sumi K, Iguchi H, Ito S, Doi T, Hamakubo T, Naito M, Auwerx J, Yanagisawa M, Kodama T, Sakai J. Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor delta induces fatty acid β-oxidation in skeletal muscle and attenuates metabolic syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 15924–15929, 2003. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306981100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tonkonogi M, Sahlin K. Rate of oxidative phosphorylation in isolated mitochondria from human skeletal muscle: effect of training status. Acta Physiol Scand 161: 345–353, 1997. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201X.1997.00222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Totland GK, Madsen L, Klementsen B, Vaagenes H, Kryvi H, Frøyland L, Hexeberg S, Berge RK. Proliferation of mitochondria and gene expression of carnitine palmitoyltransferase and fatty acyl-CoA oxidase in rat skeletal muscle, heart and liver by hypolipidemic fatty acids. Biol Cell 92: 317–329, 2000. doi: 10.1016/S0248-4900(00)01077-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vaughan RA, Garcia-Smith R, Bisoffi M, Conn CA, Trujillo KA. Conjugated linoleic acid or omega 3 fatty acids increase mitochondrial biosynthesis and metabolism in skeletal muscle cells. Lipids Health Dis 11: 142, 2012. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-11-142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xu HE, Lambert MH, Montana VG, Parks DJ, Blanchard SG, Brown PJ, Sternbach DD, Lehmann JM, Wisely GB, Willson TM, Kliewer SA, Milburn MV. Molecular recognition of fatty acids by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors. Mol Cell 3: 397–403, 1999. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80467-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]