Highlights

-

•

Benign mesenchymal tumours are commonly located in the extremities.

-

•

Incidence of soft tissue sarcoma is 1 in 100 of all soft tissue tumours.

-

•

Clinical findings including imaging and immunohistochemistry play a vital role in the diagnosis.

-

•

Multidisciplinary approach is required from the outset to ensure best patient outcome.

Keywords: Mesenchymal tumour, Asymptomatic patient, Benign, Histology

Abstract

Introduction

Soft tissue mesenchymal tumours are a common occurrence in surgical practice with particular predilection for the extremities. Approximately 1 in 100 soft tissue tumours are found to be sarcomas. The main concern is to exclude any evidence of malignancy. Both imaging studies and a detailed histological analysis is required to ensure that a diagnosis of a high-grade tumour is not missed.

Presentation of case

Here we present a 38-year-old previously fit and well gentleman with a slowly growing lump in the upper aspect of his abdomen over the previous year being completely asymptomatic from it. He underwent ultrasound, computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging of the lump. He underwent ultrasound guided biopsy with eventual wide local excision of the lump for a complete histological assessment. This was noted to be a soft tissue mesenchymal tumour.

Discussion

We highlight the importance of review of the literature and the use of markers that enable histopathologist reach an eventual diagnosis. Mesenchymal tissue during development differentiates into fat, skeletal muscle, peripheral nerves, blood vessels and fibrous tissue. Thereby any of these components may give rise to a tumour. In the majority of cases, the patient is asymptomatic unless there is invasion of nerve sheath or the effects of mass effect.

Conclusion

Our case is unique due to location of the tumour and its immunohistochemistry findings which required frequent and extensive discussion at our national sarcoma soft tissue meeting. The importance of surgeons working with histopathologists was also highlighted in our case.

1. Soft tissue mesenchymal tumour- a case report with review of literature

1.1. Presentation of case

We present Mr M. a 38-year-old Caucasian gentleman who had noticed a slowly growing lump in the upper aspect of his abdomen over the previous year. He had no gastrointestinal symptoms to note. He is a previously well gentleman with the only past medical history of psoriasis and psoriatic arthropathy. He did not have an operative history. He was referred to the surgical outpatient clinic at University Hospital Ayr from his General Physician. Our case is unique both in terms of location of the pathology as well as well the unique results from the immunohistochemistry analysis. We endeavour that the reader would gain insight into management of soft tissue tumours and acknowledge the need for extensive investigations to exclude underlying malignancy.

On examination, he had a firm soft-tissue lump just underneath the upper aspect of the right rectus abdominis muscle. There was no associated cough impulse and the lesion was non-tender with no evidence of sepsis. Hence there were no concerns of any underlying hernia defect that would explain the examination findings. The rest of the abdomen was noted to be unremarkable.

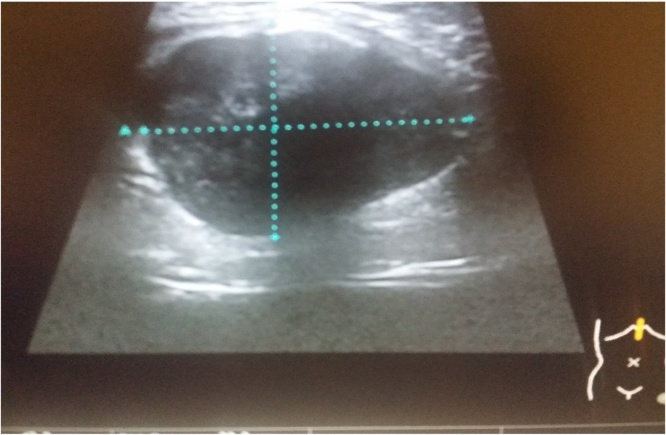

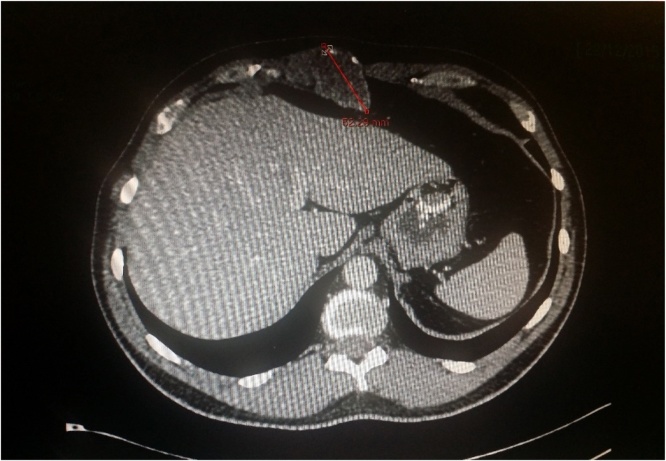

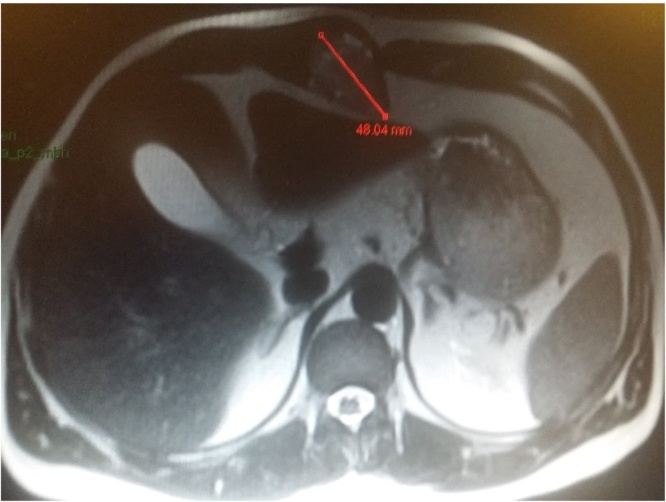

Ultrasound scan revealed a 32 mm × 30 mm × 43 mm well defined hypoechoic avascular lesion within the subcutaneous tissue (See Fig. 1). Following which the CT scan of the area confirmed a soft tissue lesion measuring 44 × 52 × 41 mm lying within right rectus sheath, partial rim of calcification with the appearance of longstanding benign lesion (See Fig. 2). He subsequently underwent a MRI scan of the abdomen which showed 4.8 × 3.2 cm well-demarcated lesion in the midline displacing the right rectus sheath, T1 isotense to soft tissue and heterogenous T2 hyperintensity, once again giving the appearance of a predominantly solid benign lesion (See Fig. 3). For a histological diagnosis, he underwent USS guided fine needle aspiration, the histology revealed appearance of low grade lesion with no evidence of malignancy and diffuse cytokeratin positivity, majority of cells being S100 negative- making PNST (Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumour) unlikely and HMB was 45 negative. His case was discussed at the local sarcoma MDT meeting and the outcome was for local excision of the lesion. There was no delay between the outcome from the sarcoma MDT and the date of local excision of the tumour.

Fig. 1.

Ultrasound scan of the mass.

Fig. 2.

CT scan of abdomen and pelvis focussed on the lesion.

Fig. 3.

MRI scan of the abdomen focussing on the lesion.

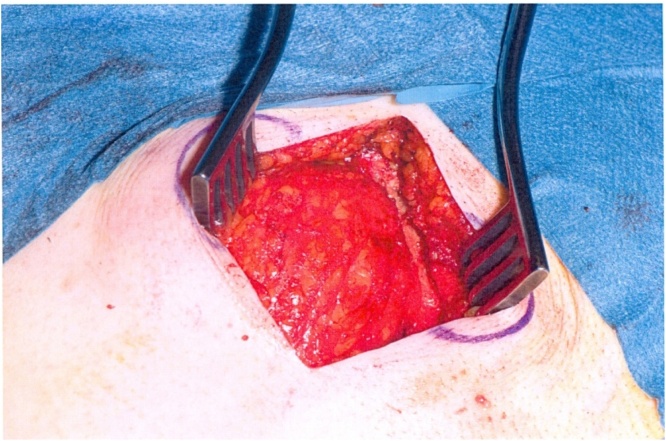

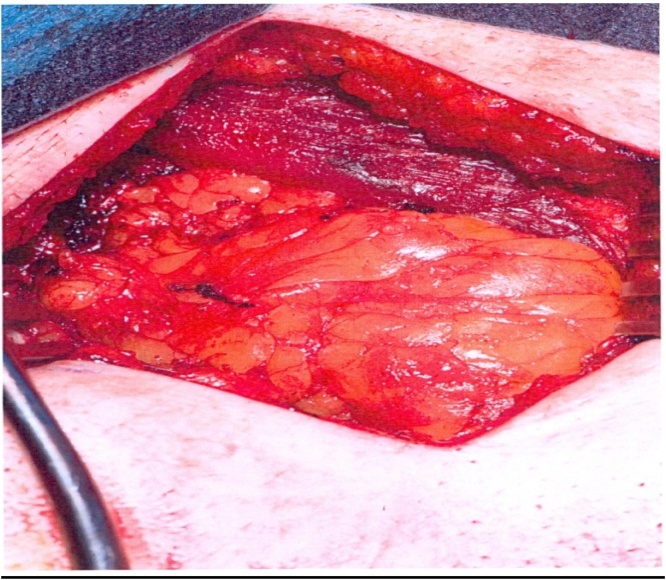

We proceeded with wide local excision of the soft tissue tumour. As our patient was otherwise a fit and well patient there were no surgical or anaesthetic concerns pre-operatively. The procedure was carried by the two co-authors of this article who are both Consultant General Surgeons working at University Hospital Ayr. Intra-operatively the lesion was noted to be involving the rectus muscle completely including the anterior and posterior sheath measuring 6 × 4.5 cm (See Fig. 4, Fig. 5). The excision had left behind a large defect (See Fig. 6) over the extra peritoneal fat with the peritoneum intact. The tumour was not noted to be infiltrating any surrounding structures and was felt to be well contained within it. The muscle defect was repaired with a sublay mesh. The rectus muscle was closed over it, as there was a defect in the anterior sheath the defect was closed with an Ultrapro(™) (Ethicon) mesh in an onlay manner. His recovery on the ward was uneventful following which he was discharged with a plan to follow up after 6 weeks. He was followed upon two separate occasions; the initial follow up was to ensure that there were no complications post procedure. The second follow up was following discussion of his case in the national sarcoma MDT with the final histopathological diagnosis.

Fig. 4.

Lesion noted in situ prior to excision.

Fig. 5.

Lesion ex-vivo.

Fig. 6.

Defect in the posterior sheath.

1.2. Histology findings

Microscopy of the specimen revealed a well circumscribed tumour with a surrounding capsule of variable thickness. Additionally, there was presence of pleomorphic spindle cells, myxoid stroma with no associated areas of necrosis with low mitotic rate. The margins were noted to be clear.

With regards to the immunohistochemistry staining it was noted to be positive with AE 1/3, EMA and MNF 116. There was focal staining with CD34, CK7 and S100. It was noted to be negative with SMA, Desmin, DOG1, CK-KIT, bcl-2 and calretinin. Ki67 was noted to be low at <5%, this indicated that the lesion is unlike to display malignant transformation. The stronger the positivity for Ki67 is associated with a greater chance of malignant transformation.

2. Discussion

From a surgical perspective, the term soft tissue tumour raises concern of the possibility of sarcoma to the discerning surgeon. Although the differentials for soft tissue tumours are large, this remains the most important single diagnosis to exclude.

Through this discussion our aim is to consolidate the overall existing knowledge of the reader on the diagnosis and management of soft tissue tumours using our case. It is beyond the scope of this article to discuss the individual soft tissue tumours in detail.

2.1. Epidemiology

As previously mentioned, 1 in 100 soft tissue tumours turn out to be sarcoma. The annual incidence of benign soft tissue tumours is 3000/million population [1] whereas that of soft tissue sarcoma is 30/million population [2], [3]. Soft tissue sarcomas are slightly more common in males and become more common with age with the median age being 65 years [2].

2.2. Imaging

With regards to imaging, ultrasonography is usually the baseline investigation of the palpable lesion. In our case, the ultrasonography revealed a well-defined hypoechoic and avascular lesion which would be the typical ultrasound findings of a benign lesion. As the nature of the lesion was uncertain a Computed Tomogram of the area of concern was undertaken. This revealed a well-defined soft tissue lesion with poorly enhancing evidence of calcification. The appearances were noted to be that of a longstanding benign lesion. Once again, the scan could not define the exact nature of the lesion however had suggested that there was no sarcomatous tissue changes. Further to this our patient underwent Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the abdomen; this revealed a 4.8 × 3.2 cm well-demarcated lesion in the midline which displaces the right rectus abdominis muscle with a fat plane separating the lesion and muscle. It was noted to be isointense in the T1 phase to soft tissue and heterogenous hyperintensity in the T2 phase. There may certain features on imaging which may characteristic of a type of soft tissue tumours. MR imaging is noted to be superior than any of the other modalities of imaging due to its high soft-tissue contrast and its field of view. For characterisation of the tissue MR is noted to be superior to CT, in addition it allows for tumour staging, pre-operative planning as well as indicating any neurovascular involvement.

Radiographs have a limited role in evaluating soft tissue tumours, however certain features if present may indicate an underlying ongoing sinister process. The role of radiographs as an adjunct with MR images are useful, for two main purposes- changes in the bone and deposition of calcium.

2.3. Immunohistochemistry

There are a range of markers which are used in the investigation of soft tissue tumours. S-100 protein is noted to be a useful immunohistochemistry marker for Schwann cells that was introduced in the past, present studies have confirmed that S-100 protein-immunoreactive Schwann cells are the primary composition of schwannoma [4]. CD34 is another marker for nerve sheath cells and is expressed in many soft tissue tumours. Cases where there has been malignant transformation, the authors have suggested that immunohistochemistry may be used to differentiate benign from malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours (MPNST). They have gone ahead to state that malignant lesions show greater positivity for p 53 and Ki-67 proteins and are less diffusively positive for S-100 protein [5], [6], [7]. In our case, there was focal staining for S-100 protein however with <5% positivity for Ki-67, this further indicated that the lesion was of low grade with a very small risk of transformation into a malignant lesion.

Our case is unique from the immunohistochemistry analysis, there was minimal focal staining with S100 and CD34. The presence of staining with S100 is associated with non-mesenchymal malignant tumours. In vascular sarcomas, there is noted to be focal staining with CD34 especially with spindle cell angiosarcoma and in our case this was initially thought. This prompted a further review from a histological point of view.

2.4. Management

There are no specific guidelines highlighting the management of soft tissue tumours here in the United Kingdom. However, the British Sarcoma Group (BSG) has incorporated the guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) [8] (US based) and those developed by the European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO) [9] into clinical practice. Although soft tissue sarcomas are a relatively rare form of malignancy, its early detection and management is of paramount importance to the clinician.

The presence of certain characteristics [10] raise the clinical suspicion of a soft tissue tumour (STS). The best single individual indicator being that of increasing size. Other features include, size of >5 cm, deep to the fascia and may/may not be painful. Approximately 99% of benign soft tissue are superficial with 95% being less than 5 cm in diameter [11]. The recommendation is that the presence of any of these characteristics would warrant referral to a diagnostic centre for suspected STS.

The standard therapy for soft tissue tumours is surgical resection. In our case, it was noted to be low grade deep and less than 5 cm in dimension, as per the ESMO guidance this warranted wide excision of the lesion. In fact, for all patients with resectable disease would benefit from wide local excision. Although our case was benign soft tissue tumour, it is recommended that an intact fascial layer or 1 cm of normal tissue would be deemed to be of sufficient margin.

There is no published data highlighting the follow up needed for patients with STS and the consensus varies across centres. With regards to follow up in our case, we sought advice from the National Sarcoma MDT meeting. The outcome was for regular surgical review of our patient without the additional need for a more extensive follow up.

3. Conclusion

Through our case we have highlighted the presentation of soft tissue mesenchymal tumour and the need to exclude soft tissue sarcoma as a likely differential. The main learning points that we identified in our case were largely based on having a high clinical suspicion in excluding an underlying malignant process. We also highlighted that even in the absence of UK based guidelines for dealing with benign soft tissue tumours, the basic work up and management rationale remains the same as for all soft tissue tumours.

Both microscopy and immunohistochemistry play a vital role for its confirmatory diagnosis and when the immunohistochemistry markers are not typical, a re-evaluation is warranted. We found that all cases went via the local soft tissue sarcoma MDT before definitive management was carried out as was highlighted in our case.

Conflicts of interest

The authors for the paper declare that they have no conflicts of interest. The authors are solely responsible for the information and the write up of this paper.

Funding

The authors for this paper have received no grants or funds for this study from any institutions or educational bodies.

Ethical approval

The patient involved in this case has given written approval.

Consent

Informed written consent was obtained from the patient for this publication and use of the images for this publication and for the use of accompanying images for educational purposes.

Author contribution

Mr. Michal Chudy-Assisted in the operation of the individual.

Mr. Sanjeet Bhattacharya-Assisted in writing this paper.

Debkumar Chowdhury- Reviewing Literature and writing of this paper.

Guarantor

All the authors involved are guarantor in this case.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the patient for allowing the case to be shared for educational purposes.

References

- 1.Rydholm A. Management of patients with soft-tissue tumors Strategy developed at a regional oncology center. Acta Orthop. Scand. Suppl. 1983;203:13–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gustafson P. Soft tissue sarcoma. Epidemiology and prognosis in 508 patients. Acta Orthop. Scand. 1994:1–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parker S.L., Tong T., Bolden S., Wingo P.A. Cancer statistics, 1996. CA. Cancer J. Clin. 1996;46:5–27. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.46.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McGee R.S., Ward W.S., Kilpatrick S.E. Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumor: A Fine-Needle Aspiration Biopsy Study. Diagn. Cytopathol. 2016;17(4):298–305. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0339(199710)17:4<298::aid-dc12>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Domanski H.A., Akerman M., Engellau J. Fine-needle aspiration of neurilemoma (Schwannoma). A clinicocytopathologic study of 116 patients. Diagn. Cytopathol. 2016;34(6):403–412. doi: 10.1002/dc.20449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mikami Y., Hidaka T., Akisada T. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor arising in benign ancient schwannoma: a case report with an immunohistochemical study. Pathol. Int. 2000;50:156–161. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1827.2000.01019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.White W., Shiu M.H., Rosenblum M.K., Erlandson R.A., Woodruff J.M. Cellular schwannoma. A clinicopathological study of 57 patients and 58 tumors. Cancer. 1990;66(September (6)):1266–1275. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19900915)66:6<1266::aid-cncr2820660628>3.0.co;2-e. (15) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology, Soft Tissue Sarcoma Version 2.2008, National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc., 2008.

- 9.Casali P.G., Jost L., Sleijfer S., Verweij J., Blay J.-Y. Soft tissue sarcomas: ESMO clinical recommendations for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2008;19(Suppl. 2):ii89–ii93. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson C.J.D., Pynsent P.B., Grimer R.J. Clinical features of soft tissue sarcomas. Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl. 2001;83(3):203–205. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Myhre-Jensen O. A consecutive 7-year series of 1331 benign soft tissue tumours Clinicopathologic data. Comparison with sarcomas. Acta Orthop. Scand. 1981;52:287–293. doi: 10.3109/17453678109050105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Further reading

[12] R.A. Agha, A.J. Fowler, A. Saetta, I. Barai, S. Rajmohan, D.P. Orgill, SCARE Group. The SCARE statement: consensus-based surgical case report guidelines, Int. J. Surg. (2016) (in press).