Abstract

We present a novel strategy based on data independent acquisition coupled to targeted data extraction for the detection and identification of site specific modifications of targeted peptides in a completely unbiased manner. This method requires prior knowledge of the site of the modification along the peptide backbone from the protein of interest but not the mass of the modification. The procedure named Multiplex Adduct Peptide Profiling (MAPP) consists of three steps: 1) A fragment ion tag is extracted from the data which consists of the b-type and y-type ion series from the N- and C-terminus, respectively, up to the amino acid’s position that is believed to be modified; 2) MS1 features are matched to the fragment ion tag in retention time space using the isolation window as a pre-filter allowing for calculation of the mass of the modification; and 3) Modified fragment ions are overlaid with the unmodified fragment ions to verify the mass calculated in step 2. We discuss the development, applications and limitations of this new method for detection of peptide modifications in a discovery nature. We present an application of the method in profiling adducted peptides derived from abundant proteins in biological fluids in ultimate efforts to detect biomarkers of exposure to reactive species.

Keywords: Protein Adducts, Toxicoproteomics, Mass Spectrometry, Data Independent Acquisition, Exposome

Introduction

Technological advancements in instrumentation [1–3], sample preparation [4–7], and bioinformatics [8–13] have made LC MS/MS the premiere analytical method for global proteomics with the identification of several thousands of proteins in a single injection analysis routine [2]. However, protein identification and quantification only provides a limited view of the altered biological pathways and networks that contribute to complex human diseases such as cancer. Most all proteins are modified post-translationally by a diverse set (n>200) of molecules. Protein modifications can be either enzymatically driven or a result of chemical (i.e., non-enzymatic) modifications – often due to reactive electrophiles created from the metabolism of exogenous compounds or a result of by-products of endogenous biological processes (e.g., reactive oxygen/nitrogen species) [14,15]. The former diversifies protein function while the latter may lead to altered or inhibition of function and; thus, is often referred to as protein damage [16,17]. Damaged proteins can have adverse biological effects and have been implicated in various age related diseases (e.g., neurological, atherosclerosis, diabetes mellitus) [18].

As a result, a more thorough understanding of the biological processes mediated/affected by both enzymatic and chemical modifications of proteins in relation to disease is imperative. However, detection of protein modifications by LC MS/MS have been limited. These techniques are often are focused on the presence/abundance of a single enzymatic or chemical protein modification [19]. Detection of modified proteins encompasses several analytical challenges including: 1) modified proteins are often present at sub-stoichiometric levels requiring the need for enrichment strategies; 2) For bottom-up proteomic strategies, detection of a modified protein is dependent on having a proteotypic peptide that contains the amino acid that is modified; and 3) limitations of current LC MS/MS acquisition/analysis techniques. All limitations represent key areas where significant technology improvement is needed.

Traditional discovery workflows using LC MS/MS require prior knowledge of the mass of the modification and variable modification searches. This approach has 3 principal limitations: 1) Multiple modification searches exponentially increase data analysis times limiting most searches to a few known modifications; 2) Identification is ultimately dependent on the modified peptide being sampled by data dependent acquisition – a process known to be semi-stochastic and biased towards the identification of abundant species [20] and; 3) These workflows only identify known protein modifications that are included as variable modifications in the database search. The latter may be the most noteworthy limitation as it biases identification and stifles discovery of novel modifications. Other methods in proteomics include the burgeoning field of targeted proteomics [21,22], but this technique also requires prior knowledge of the elemental composition of the modification such that appropriate precursor-fragment transitions can be chosen.

Data independent acquisition (DIA) [23] coupled to targeted data extraction [24,25] has offered an alternative workflow for analysis of proteomic samples using LC MS/MS. DIA methods are based off fragment scans of wide isolation windows but can vary between 2 and greater than 100 m/z [26,25,23,27,28]. Although conventional data dependent acquisition strategies are extremely powerful for surveying proteomes [2], methods based on independent acquisition offer certain benefits. The principal advantages are improved reproducibility of peptide identifications due to the sequential scanning of isolation windows, potential improvements in quantitative accuracy due to improvements in signal to noise of MS2 versus MS1 based label-free quantitation, and when coupled to targeted data extraction the capability to re-query a dataset for any peptide of interest. Essentially, one can propose questions and test hypotheses in the data.

Herein, we describe an LC MS/MS method named Multiplex Adduct Peptide Profiling (MAPP) to profile protein modifications without prior knowledge of the modification. The method consists of three steps in which putative signals of interest are identified using the extraction of a fragment ion tag, the mass of the modification is calculated by matching the fragment ion tag to the appropriate precursor in retention time space, and verification of the mass of the modification. The method relies on protein enrichment and targeted data extraction [24,25] coupled to data independent acquisition [23]. It can be used to investigate site specific heterogeneity of targeted peptides of interest when the modification may be unknown. We discuss the development of the method including limitations and demonstrate its potential to profile global adducts of two high abundant proteins (serum albumin and hemoglobin) due to covalent modifications by reactive electrophiles in biological fluids. Reactive electrophiles are believed to be a major contributor to complex human diseases as they directly modify biopolymers [19,29]. Reactive electrophiles compose a significant part of an individual’s exposome [30] which represents the totality of all exposures from conception onward and is an emerging area in disease research due to continued studies that suggests primary genetic factors often do not explain a majority of complex human disease risk [31].

Methods

Materials

Formic acid (FA), ammonium bicarbonate (AB), hydrochloric acid (HCl), iodoacetamide (IAM), dithiothreitol (DTT), sodium deoxycholate (SDC) were obtained from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Trypsin was obtained from Promega (Madison, WI). HPLC grade acetonitrile, methanol and water were from Burdick & Jackson (Muskegon, MI). The hemoglobin peptide (GTFATLSELHCDK) was synthesized and purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific GmbH (Ulm, Germany). Pooled plasma and blood obtained from smokers was purchased from BioreclamationIVT (New York, New York).

NanoLC MS/MS

2 μL of sample were injected onto a self-made 4 cm trap using an Easy nanoLC 1000 coupled to a Q Exactive Plus mass spectrometer (Bremen Germany). PicoFrit columns from New Objective (Woburn, MA) were packed to 25 cm in house with 3 μm C18 silica particles (Dr. Maisch, Entringen, Germany). Mobile phase B was 99.9 % acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid and mobile phase A was 98 % water, 2 % acetonitrile, and 0.1 % formic acid. A 90 minute LC MS/MS method was used and consisted of a linear gradient from 0–40 % B over 70 minutes followed by a ramp to 80 % B in one minute. The column was washed at 80% B for 9 minutes and regenerated at 0 % B for 10 minutes.

Albumin and hemoglobin Isolation/Enrichment

Albumin isolation and adduct enrichment were performed based upon the method describe elsewhere[32]. In brief, ammonium sulfate was added to 4 mL of plasma to create a 60% saturated solution. Albumin was acid precipitated using HCl from the supernatant. Isolated albumin (500 μg) was added to 75 mg of dry Activated Thiol Sepharose in a spin column and the flow through fraction (nonmercaptoalbumin) was collected after 18 hours of enrichment. The enriched albumin fraction was then prepared using the filter-aided sample preparation procedure for shotgun proteomics.[7] Samples were digested for 4 hours at a trypsin to substrate ratio of 1:50. Hemoglobin and albumin sample preparation including isolation, enrichment, and digestion are described in detail in supplemental materials.

DIA Methods were created in Skyline.[33] The 21 amino acid tryptic peptide from human serum albumin that contained the free Cys34 residue was entered into skyline (K.ALVLIAFAQYLQQCPFEDHVK.L). An isolation list was created in Skyline that used 12 10 m/z isolation windows which spanned m/z 810 to 930 but still contained the triply charged unmodified peptide precursor (m/z 811.7594). This range of precursor detection included the mass of the albumin free cysteine unadducted peptide to a mass addition (i.e., adduct) of 360 Daltons which encompasses the masses of all reported protein adducts aside from Satratoxin G[19]. A similar procedure was used for the development of the method to monitor the tryptic peptide from beta chain of hemoglobin that contained the free cysteine (GTFATLSELHCDK).

The isolation list was imported into the method editor of the Q Exactive Plus and an MS1 scan was added every 12th scan from m/z 550 to 1300 for a maximum duty cycle of less than 1.5 seconds. For the MS1 scan the resolving power was set to 70,000 at m/z 200, an AGC of 1e6, and a max injection time of 50 ms was used. For the DIA scans, parameters were set to the given levels: AGC of 1e6, 30 NCE (normalized collision energy), max injection time of 50 ms, and a resolving power of 17,500 at m/z 200.

Data Analysis

In Skyline, precursors of increasing mass were created by adding artificial modifications to the Cys34 or Cys93 of the targeted albumin peptide or hemoglobin peptide, respectively. This step was performed solely to have Skyline extract the common fragment ions of the adducted peptide within each isolation window. Putative signals of interest (SOI) were identified by extracting common fragment ions from the Cys34 adducted peptides and finding the instances in retention time space where all co-eluted with high mass measurement accuracy (<5 ppm). In addition, the proportion of relative abundances of each fragment to total abundance was used as a method to eliminate false positives. Once an SOI was identified, precursors were filtered based on the isolation window from which the SOI originated and matched in retention time space with the SOI using Xcalibur 2.2. This matching was based on the principle that since the MS1 precursor and associated fragment ions all belong to the same chemical species then the chromatographic profile of both should be theoretically identical.

Unique Ion Signature

SRM Collider[34] was used to further investigate the uniqueness of the common detected fragment ions (i.e., the signal of interest). This tool was originally developed for selected reaction monitoring experiments but can be used to assess the uniqueness of co-elution of fragment ions in data independent acquisition experiments with the appropriate settings. The following settings were used: Q1 mass window was set to 10 m/z (i.e. width of isolation window); Q3 mass window was set to 0.05 m/z, m/z range from 300–1500, 3 isotopes to consider, 0 missed cleavages, and the consideration of both b- and y-type fragment ions from the human tryptic database. Transitions that were routinely detected were y3–y7 and b3–b6 for HSA Cys34 peptide. For the hemoglobin Cys93 peptide, b4 – b10 were detected. Based on the parameters, the detection and coelution of any combination of at least 4 of these fragment ions results in a unique ion signature (UIS) specific to the peptide of interest.

Results/Discussion

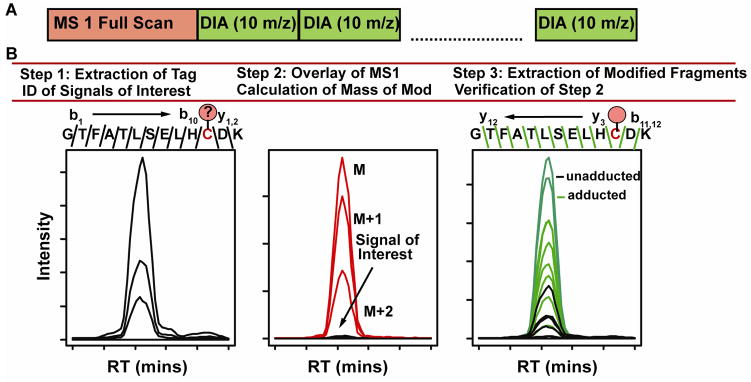

Figure 1 displays the overall workflow for peptide adduct studies by data independent acquisition mass spectrometry using a targeted data analysis. The method consists of a 1 dimensional reversed phase liquid chromatographic separation followed by data independent acquisition with a dedicated MS1 full scan (Figure 1A). Relatively wide isolation windows (m/z=10) at fixed incremental m/z increases are used to detect signals of interest (SOI). Data analysis and interpretation then follows a 3 step process. In the first step, a fragment ion tag is extracted from the data that consists of the b-type ion series and y-type ion series from the respective termini to the amino acid that is believed to be modified. Since this fragment ion tag does not contain the amino acid that is potentially modified, then all modified peptides will have this ion signature. It is important to note that this step makes the assumption that all peptide adducts will behave in a similar way upon collision induced dissociation. The point in retention time at which these fragment ions co-elute in the chromatogram represents a signal of interest. In step 2, MS1 signals are overlaid with the signal of interest to match the precursor with corresponding fragment ions. The ambiguity in the correct MS1 feature is greatly reduced by only considering the precursors resulting from the isolation window at which the signals of interest (i.e., fragment ions) were generated. The degree of this complexity reduction is inversely proportional to the width of the isolation window. In addition, the assumption that an adducted peptide would have the same charge state and a greater m/z than the unmodified peptide excludes many MS 1 features. Next, based on retention time apex and peak shape, a putative precursor m/z representing the modified peptide can be identified. The signal can be further confirmed if the M, M+1 and M+2 precursor ions are extracted. Then the mass of the modification can be calculated using Equation 1.

Figure 1.

An overview of the method used for Multiplex Adduct Peptide Profiling (MAPP). The scan cycle consists of a full MS1 scan followed by DIA scans. Data analysis consists of three steps for the identification of global peptide modifications. Step 1 identifies potential signals of interest (SOI) by extracting the masses of unmodified fragment ions (i.e., tag). Step 2 calculates the mass of the modification by matching co-eluting MS1 features to the fragment ion tag extracted in step 1. Step 3 verifies the calculation in step 2 by extracting the modified fragment ions. An alkylated tryptic peptide from the beta chain of hemoglobin was used to illustrate the workflow.

| Equation 1 |

Finally, in step 3 the mass of the modification can be verified by extracting the fragment ions that contain the modification calculated from step 2. If the mass is identified correctly, then coelution of additional adducted fragment ions should be observed. It is important to note that this step assumes that the modification is stable upon collision induced dissociation which will not be the case in all instances. Figure 1B summarizes the overall workflow using the tryptic peptide which contains a free cysteine (Cys93) from the beta chain of hemoglobin that has been carbamidomethylated.

This procedure represents a powerful strategy to identify both the number of putative modifications of a targeted peptide in complex mixtures or enriched samples and identification of those modifications through accurate mass analysis. In theory each modification changes the hydrophobicity of the peptide which then can be separated in time by reversed phase chromatography. By counting the number of different peaks resulting from co-elution of the unmodified fragment ions (i.e., signal of interest) one can determine the putative number of peptide adducts.

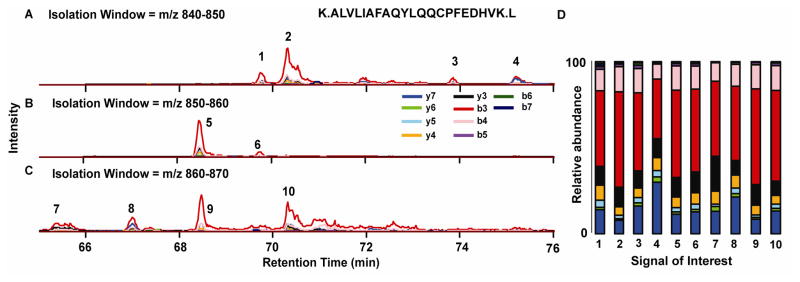

Figure 2 displays data from the LC MS/MS analysis of human plasma after enrichment of modified mercaptoalbumin (Cys34) using the method described with an isolation window of 10 m/z. Human serum albumin and the tryptic peptide containing Cys34 have been used for detecting peptide adducts in biological fluids[35–37] including those related to smoking.[38] The width of the isolation window is an important parameter as large isolation windows decreases the sensitivity of peptide adduct detection in complex mixtures (see Electronic Supplementary Material (ESM) Fig. S1) by MAPP but inherently allows for a larger m/z space to be interrogated in a single run. First, unmodified fragment ions were extracted and three of the isolation windows are shown. Several signals of interest were observed as identified by co-elution and accurate mass (<5 ppm) of the unmodified fragment ions. For the majority, the adducts had little effect on retention time using our standard 90 minute run and eluted between 65 and 76 minutes. The ratio of the unmodified fragment ions can be used to help ensure positive identification of a putative peptide adduct and limit false positives. All 10 putative peptide adducts observed from these isolation windows, had similar relative fragment ion abundances as illustrated in Figure 2B. The most abundant fragment ion was the b3 ion followed by the y7 ion. Interestingly the Cys34 tryptic peptide contains a proline amino acid (y7) which is known to preferentially fragment (N-terminal) upon collision induced dissociation. [39,40]

Figure 2.

A–C) A display of chromatograms from three isolation windows where unmodified y+ and b+ fragment ion series were extracted from the LC MS/MS analysis of the enriched Cys34 albumin peptide. Within these three windows, 10 signals of interest (SOI) were identified. D) Comparison of the relative abundance of each SOI shows a similar ion fragmentation signature. The b3 and y7 ions were found to be typically most abundant.

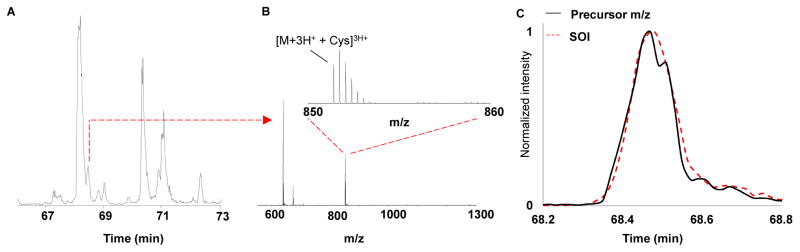

It is important to note at this point in the data analysis procedure that we have identified the number of potentially modified forms of a single peptide – a feat that is difficult to perform by current technologies. However, we add to these new capabilities, by matching the monoisotopic mass of the precursor ion to the SOI in retention time space. Figure 3 displays this process for SOI #5. The retention time of interest is obtained from the tag (SOI#5=68.5 mins). Then the full MS1 mass spectrum is inspected at that particular retention time. One can gain further specificity by only considering the MS 1 features in the m/z range from the isolation window that created SOI # 5 (Figure 3B). In this particular example, the m/z range was not complicated and the precursor m/z that resulted in the SOI#5 was readily determined to be 851.4266 and verified by investigating the elution profiles of the tag (SOI#5) and precursor (Figure 3C). It’s important to note the efficacy of this step is heavily dependent on sample complexity, isolation window width, and peak capacity. More robust tools and statistics are needed to provide a confidence in the match between the elution profiles of the MS1 and signal of interest. Once the precursor m/z is accurately determined, an exact mass of the adduct can then be calculated using Equation 1.

Figure 3.

A) An expanded base peak chromatogram (66 to 73 mins) of the MS 1 filtered scans. The signals of interest indicate the retention time to investigate the precursor scan in efforts to match the SOI with its precursor m/z. B) The full mass spectrum at 68.5 mins is shown which corresponded to SOI # 5. The full scan can be further filtered to only show the precursors from the isolation window (inset) from which SOI # 5 was generated (m/z 850–860). C) A comparison between the elution profile of the putative precursor and SOI can be used to provide confidence in the match. The y axis was normalized to the maximum intensity of the summed fragment ions for SOI # 5 and the extracted monoisotopic mass in order access similarity in elution profiles. SOI #5 was found to match the precursor 851.4261 in retention time space which was due to cysteinylation.

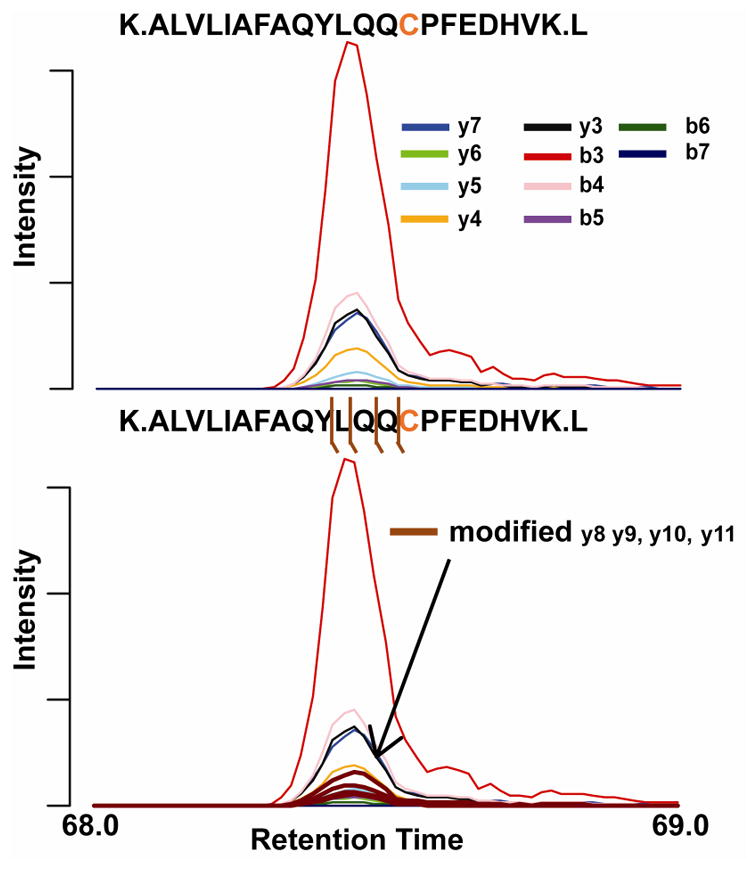

For SOI #5, the mass of the modification was calculated to be 119.004 Da. Searching previous literature, it was discovered that this mass is a common albumin adduct in biological fluids in which a thiol bond is created between two cysteine residues – known as cysteinylation. The verification step adds this mass to the Cys34 residue and then overlays the modified fragment ions. Coelution of multiple fragment ions extracted with the elucidated mass provides confirmation that the peptide is believed to be adducted with the mass calculated. It is important to note that this final step will not be possible for some modifications and is dependent on the stability of the modification upon collision induced dissociation. In addition, the fragmentation efficiency and overall abundance of the peptide adduct will play a role as well. Interestingly, increased human serum albumin Cys34 cysteinylation has been shown to be a marker for oxidative stress related diseases such as diabetes mellitus and chronic liver and kidney diseases.[41]

Thirty-six signals of interest were observed which represent putative adducts of Cys34 albumin tryptic peptide using coelution of fragment ions and accurate mass analysis across the 12 isolation windows. A list of peptide adducts that were identified are given in Table 1. Several of these identified adducts have been previously reported in the literature [42]. The list consists of varying degrees of cysteine oxidation including sulfenic (SOH), sulfinic (SO2H), and sulfonic acids (SO3H). Di- and Trioxidation were most prevalent. Several SOIs could not be identified due to the lack of resources (ie. databases) available for known peptide adducts and software to streamline the data mining. Also it is worth noting that some of these SOIs are likely due to in vitro modifications (i.e., sample handling/storage) to the cysteine, modifications of other residues (e.g., Gln), or a combination of both. With improved software and extraction methods, pinpointing the site of modification could be performed using the common and modified fragment ions as shown previously to assign sites of methionine oxidation [24]. Regardless, MAPP presents a powerful strategy to profile targeted peptide modifications in a discovery manner in proteomic samples.

Table 1.

Peptide adduct identifications from human plasma of the Cys34 albumin tryptic peptide. MMA corresponds to the identified precursor peptide adduct. Confidence intervals represent standard deviation in 6 technical replicates. Names correspond to UNIMOD format

| Observed m/z | Theoretical m/z | Calculated Adduct Mass (Da) | MMA (PPM) | Ret Time (min) | Putative Adduct |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 811.7589 | 811.7594 | ——— | 0.6 (± 0.2) | 72.3 (± 0.2) | Unadducted |

| 817.0928 | 817.0910 | 16.0002 | 1.3 (± 1.3) | 70.6 (± 0.2) | Oxidation |

| 822.4227 | 822.4229 | 31.9899 | 0.8 (± 0.1) | 72.2 (± 0.2) | Dioxidation |

| 827.7537 | 827.7546 | 47.9829 | 0.8 (± 0.1) | 72.6 (± 0.2) | Trioxidation |

| 851.4261 | 851.4272 | 119.0001 | 0.9 (± 0.2) | 68.5 (± 0.2) | Cysteinyl |

| 856.0988 | 856.0993 | 133.0197 | 1.0 (± 0.4) | 68.6 (± 0.2) | HCysteinyl |

| 913.4483 | 913.4487 | 305.0682 | 0.6 (± 0.4) | 68.7 (± 0.2) | Glutathione |

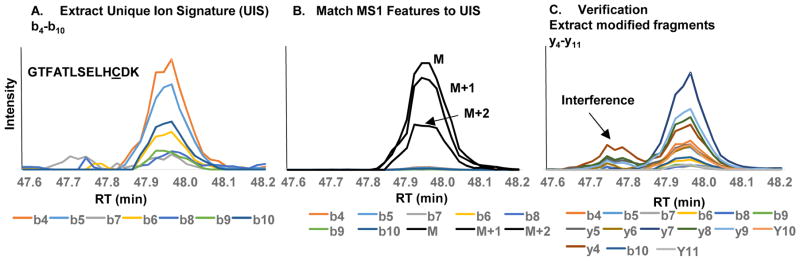

In theory, MAPP can be used to investigate modifications of any targeted peptide(s) of interest. To provide another example, we isolated hemoglobin from blood (See Supplemental Section) and analyzed the peptide that contains the free cysteine (GTFATLSELHCDK) from the beta chain of hemoglobin. All b-type fragment ions from the N-terminus up to the free cysteine (Cys93) were extracted (b4–b10). Since this amino acid of interest resided near the C terminus of the tryptic peptide, we did not extract any of the y fragment ions. Similar to the albumin study, both di and tri oxidation forms were readily observed (see ESM, Table S1). However, Figure 5 shows the power of MAPP to detect unanticipated/unknown modifications that would likely have never been detected by traditional database approaches. In this example, the modification was elucidated using MAPP to have a mass of 170.1208 Daltons but could not be readily identified based on previous reports and available databases. To confirm positive detection of hemoglobin Cys93 adducts, the sample was analyzed by a traditional data dependent acquisition workflow using the quadrupole orbitrap. The raw data was searched using a variable modification search which included cysteine oxidation and the mass of the unknown modification (170.1208 Da). Spectra matching all three hemoglobin cysteine adducts were identified by DDA with high confidence (posterior error probability < 0.01)[43].

Figure 5.

A) Extraction of a signal of interest associated with the free cysteine containing hemoglobin peptide. B) Overlay of matching MS 1 features including M, M+1 and M+2. C) Extraction of fragment ions with the modification determined to be 170.1208 Da. We found there to be interference in some of the modified fragments ions upon extraction.

Future applications will utilize MAPP to investigate the adductome in relation to diseases due to environmental causes. In addition, we will investigate the capability to provide an adduct fingerprint in efforts to classify exposures to complex substances (cigarette smoke, air pollution etc) from human epidemiological studies. Further work is ongoing to develop normalization procedures for peptide adduct quantitation, more objective metrics/statistics for identification, and automated workflows for matching MS1 to unique ion signatures (UIS).

Conclusions

A novel method termed Multiplex Adduct Peptide Profiling (MAPP) which provides a framework to investigate multiple modifications of a single amino acid along a peptide backbone has been developed. The authors note while the initial application has focused on adductomics, it could be applied to other in vivo modifications (e.g., protein glycosylation heterogeneity) given the protein of interest could be efficiently isolated and enriched. Enrichment is typically key in these experiments since in vivo modifications occur at sub-stoichiometric levels. As with any method, certain limitations do exist. The specificity of the tag (i.e., SOI) may restrict the method’s use for small peptides in complex mixtures. As performed vide supra, the tag specificity can be evaluated using SRM collider[34] to determine if the tag represents a unique ion signature within the precursor isolation windows of interest and organism under study. In addition, the complexity of the precursor isolation window which is dependent on the separation efficiency (i.e., peak capacity), sample complexity, and the width of the isolation window is important to consider as it will affect the efficacy of matching the correct MS 1 feature to the fragment ion tag of interest. More advanced DIA techniques that improve precursor specificity by isolating nonadjacent windows could be utilized.[25]

Supplementary Material

Figure 4.

A) Extraction of the unmodified fragments of SOI #5. B) Adducted fragment ions were then extracted from the data to verify this assignment of cysteine adduction. The step is heavily dependent on the stability of the modification upon collision induced dissociation and the abundance of the peptide adduct.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge support from NC State University and a Pilot Project Award from the Center for Human Health & the Environment which supported this work.

Biographies

Caleb Porter recently obtained his Masters from North Carolina State University where he worked on the development of LC MS/MS methods for detection of environmental exposures in biological fluids.

Michael S. Bereman is an Assistant Professor in Biological Sciences at NC State University and Member of the Center for Human Health and Environment. His research is centered on the development and applications of new analytical technologies to identify biomarkers of exposures in ultimate efforts to better understand how the environment impacts human health.

References

- 1.Bereman MS, Canterbury JD, Egertson JD, Horner J, Remes PM, Schwartz J, Zabrouskov V, MacCoss MJ. Evaluation of front-end higher energy collision-induced dissociation on a benchtop dual-pressure linear ion trap mass spectrometer for shotgun proteomics. Anal Chem. 2012;84(3):1533–1539. doi: 10.1021/ac203210a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hebert AS, Richards AL, Bailey DJ, Ulbrich A, Coughlin EE, Westphall MS, Coon JJ. The one hour yeast proteome. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2014;13(1):339–347. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M113.034769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scheltema RA, Hauschild JP, Lange O, Hornburg D, Denisov E, Damoc E, Kuehn A, Makarov A, Mann M. The Q Exactive HF, a Benchtop Mass Spectrometer with a Pre-filter, High-performance Quadrupole and an Ultra-high-field Orbitrap Analyzer. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2014;13(12):3698–3708. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M114.043489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bereman MS, Egertson JD, Maccoss MJ. Comparison between procedures using SDS for shotgun proteomic analyses of complex samples. Proteomics. 2011;11(14):2931–2935. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201100045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Erde J, Loo RR, Loo JA. Enhanced FASP (eFASP) to increase proteome coverage and sample recovery for quantitative proteomic experiments. J Proteome Res. 2014;13(4):1885–1895. doi: 10.1021/pr4010019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wisniewski JR, Zougman A, Mann M. Combination of FASP and StageTip-Based Fractionation Allows In-Depth Analysis of the Hippocampal Membrane Proteome. J Proteome Res. 2009;8(12):5674–5678. doi: 10.1021/pr900748n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wisniewski JR, Zougman A, Nagaraj N, Mann M. Universal sample preparation method for proteome analysis. Nat Methods. 2009;6(5):359–U360. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Broudy D, Killeen T, Choi M, Shulman N, Mani DR, Abbatiello SE, Mani D, Ahmad R, Sahu AK, Schilling B, Tamura K, Boss Y, Sharma V, Gibson BW, Carr SA, Vitek O, MacCoss MJ, MacLean B. A framework for installable external tools in Skyline. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(17):2521–2523. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brusniak MY, Kwok ST, Christiansen M, Campbell D, Reiter L, Picotti P, Kusebauch U, Ramos H, Deutsch EW, Chen J, Moritz RL, Aebersold R. ATAQS: A computational software tool for high throughput transition optimization and validation for selected reaction monitoring mass spectrometry. Bmc Bioinformatics. 2011;12:78. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spivak M, Weston J, Bottou Lo, Käll L, Noble WS. Improvements to the Percolator Algorithm for Peptide Identification from Shotgun Proteomics Data Sets. J Proteome Res. 2009;8(7):3737–3745. doi: 10.1021/pr801109k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brosch M, Yu L, Hubbard T, Choudhary J. Accurate and Sensitive Peptide Identification with Mascot Percolator. J Proteome Res. 2009;8(6):3176–3181. doi: 10.1021/pr800982s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kall L, Canterbury JD, Weston J, Noble WS, MacCoss MJ. Semi-supervised learning for peptide identification from shotgun proteomics datasets. Nat Methods. 2007;4:923–925. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spivak M, Bereman MS, MacCoss MJ, Noble WS. Learning Score Function Parameters for Improved Spectrum Identification in Tandem Mass Spectrometry Experiments. J Proteome Res. 2012;11(9):4499–4508. doi: 10.1021/pr300234m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ray PD, Huang B-W, Tsuji Y. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) homeostasis and redox regulation in cellular signaling. Cell Signal. 2012;24(5):981–990. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Butterfield DA, Dalle-Donne I. Redox proteomics. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2012;17(11):1487–1489. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Codreanu SG, Ullery JC, Zhu J, Tallman KA, Beavers WN, Porter NA, Marnett LJ, Zhang B, Liebler DC. Alkylation damage by lipid electrophiles targets functional protein systems. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2014 doi: 10.1074/mcp.M113.032953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chondrogianni N, Petropoulos I, Grimm S, Georgila K, Catalgol B, Friguet B, Grune T, Gonos ES. Protein damage, repair and proteolysis. Mol Aspects of Med. 2014;35(0):1–71. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jaisson S, Gillery P. Evaluation of nonenzymatic posttranslational modification-derived products as biomarkers of molecular aging of proteins. Clin Chem. 2010;56(9):1401–1412. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2010.145201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rubino FM, Pitton M, Di Fabio D, Colombi A. Toward an “omic” physiopathology of reactive chemicals: thirty years of mass spectrometric study of the protein adducts with endogenous and xenobiotic compounds. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2009;28(5):725–784. doi: 10.1002/mas.20207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Michalski A, Cox J, Mann M. More than 100,000 Detectable Peptide Species Elute in Single Shotgun Proteomics Runs but the Majority is Inaccessible to Data-Dependent LC–MS/MS. J Proteome Res. 2011;10(4):1785–1793. doi: 10.1021/pr101060v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bereman MS, Maclean B, Tomazela DM, Liebler DC, Maccoss MJ. The development of selected reaction monitoring methods for targeted proteomics via empirical refinement. Proteomics. 2012;12(8):1134–1141. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201200042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Method of the Year 2012. Nat Meth. 2013;10(1):1–1. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Venable JD, Dong MQ, Wohlschlegel J, Dillin A, Yates JR. Automated approach for quantitative analysis of complex peptide mixtures from tandem mass spectra. Nat Methods. 2004;1(1):39–45. doi: 10.1038/nmeth705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gillet LC, Navarro P, Tate S, Rost H, Selevsek N, Reiter L, Bonner R, Aebersold R. Targeted data extraction of the MS/MS spectra generated by data-independent acquisition: a new concept for consistent and accurate proteome analysis. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2012;11(6):O111. doi: 10.1074/mcp.O111.016717. 016717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Egertson JD, Kuehn A, Merrihew GE, Bateman NW, MacLean BX, Ting YS, Canterbury JD, Marsh DM, Kellmann M, Zabrouskov V, Wu CC, MacCoss MJ. Multiplexed MS/MS for improved data-independent acquisition. Nat Methods. 2013;10(8):744–746. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Panchaud A, Scherl A, Shaffer SA, von Haller PD, Kulasekara HD, Miller SI, Goodlett DR. Precursor Acquisition Independent From Ion Count: How to Dive Deeper into the Proteomics Ocean. Anal Chem. 2009;81(15):6481–6488. doi: 10.1021/ac900888s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weisbrod CR, Eng JK, Hoopmann MR, Baker T, Bruce JE. Accurate peptide fragment mass analysis: multiplexed peptide identification and quantification. J Proteome Res. 2012;11(3):1621–1632. doi: 10.1021/pr2008175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Silva JC, Denny R, Dorschel CA, Gorenstein M, Kass IJ, Li G-Z, McKenna T, Nold MJ, Richardson K, Young P, Geromanos S. Quantitative Proteomic Analysis by Accurate Mass Retention Time Pairs. Anal Chem. 2005;77(7):2187–2200. doi: 10.1021/ac048455k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liebler DC. Protein damage by reactive electrophiles: targets and consequences. Chem Res Toxicol. 2008;21(1):117–128. doi: 10.1021/tx700235t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wild CP. Complementing the genome with an “exposome”: The outstanding challenge of environmental exposure measurement in molecular epidemiology. Cancer Epidem Biomar. 2005;14(8):1847–1850. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lichtenstein P, Holm NV, Verkasalo PK, Iliadou A, Kaprio J, Koskenvuo M, Pukkala E, Skytthe A, Hemminki K. Environmental and heritable factors in the causation of cancer--analyses of cohorts of twins from Sweden, Denmark, and Finland. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(2):78–85. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200007133430201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Funk WE, Li H, Iavarone AT, Williams ER, Riby J, Rappaport SM. Enrichment of cysteinyl adducts of human serum albumin. Analytical Biochemistry. 2010;400(1):61–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.MacLean B, Tomazela DM, Shulman N, Chambers M, Finney GL, Frewen B, Kern R, Tabb DL, Liebler DC, MacCoss MJ. Skyline: an open source document editor for creating and analyzing targeted proteomics experiments. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(7):966–968. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rost H, Malmstrom L, Aebersold R. A computational tool to detect and avoid redundancy in selected reaction monitoring. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2012;11(8):540–549. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.013045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rappaport SM, Li H, Grigoryan H, Funk WE, Williams ER. Adductomics: characterizing exposures to reactive electrophiles. Toxicol Lett. 2012;213(1):83–90. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li H, Grigoryan H, Funk WE, Lu SS, Rose S, Williams ER, Rappaport SM. Profiling Cys34 adducts of human serum albumin by fixed-step selected reaction monitoring. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2011;10(3):M110. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M110.004606. 004606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ghosh A, Choudhury A, Das A, Chatterjee NS, Das T, Chowdhury R, Panda K, Banerjee R, Chatterjee IB. Cigarette smoke induces p-benzoquinone-albumin adduct in blood serum: Implications on structure and ligand binding properties. Toxicology. 2012;292(2–3):78–89. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2011.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Phillips DH, Venitt S. DNA and protein adducts in human tissues resulting from exposure to tobacco smoke. International Journal of Cancer. 2012;131(12):2733–2753. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grewal RN, El Aribi H, Harrison AG, Siu KWM, Hopkinson AC. Fragmentation of Protonated Tripeptides: The Proline Effect Revisited. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2004;108(15):4899–4908. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schwartz BL, Bursey MM. Some proline substituent effects in the tandem mass spectrum of protonated pentaalanine. Biol Mass Spectrom. 1992;21(2):92–96. doi: 10.1002/bms.1200210206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nagumo K, Tanaka M, Chuang VTG, Setoyama H, Watanabe H, Yamada N, Kubota K, Tanaka M, Matsushita K, Yoshida A, Jinnouchi H, Anraku M, Kadowaki D, Ishima Y, Sasaki Y, Otagiri M, Maruyama T. Cys34-Cysteinylated Human Serum Albumin Is a Sensitive Plasma Marker in Oxidative Stress-Related Chronic Diseases. Plos One. 2014;9(1):e85216. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chung M-K, Grigoryan H, Iavarone AT, Rappaport SM. Antibody Enrichment and Mass Spectrometry of Albumin-Cys34 Adducts. Chem Res Toxicol. 2013;27(3):400–407. doi: 10.1021/tx400337k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kall L, Storey JD, MacCoss MJ, Noble WS. Posterior error probabilities and false discovery rates: two sides of the same coin. J Proteome Res. 2008;7(1):40–44. doi: 10.1021/pr700739d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.