Abstract

Objective

To develop a pan-Canadian rural education road map to advance the recruitment and retention of family physicians in rural, remote, and isolated regions of Canada in order to improve access and health care outcomes for these populations.

Composition of the task force

Members of the task force were chosen from key stakeholder groups including educators, practitioners, the College of Family Physicians of Canada education committee chairs, deans, chairs of family medicine, experts in rural education, and key decision makers. The task force members were purposefully selected to represent a mix of key perspectives needed to ensure the work produced was rigorous and of high quality. Observers from the Canadian Medical Association and Health Canada’s Council on Health Workforce, and representatives from the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada, were also invited to provide their perspectives and to encourage and coordinate multiorganization action.

Methods

The task force commissioned a focused literature review of the peer-reviewed and gray literature to examine the status of rural medical education, training, and practice in relation to the health needs of rural and remote communities in Canada, and also completed an environmental scan.

Report

The environmental scan included interviews with more than 100 policy makers, government representatives, providers, educators, learners, and community leaders; 17 interviews with practising rural physicians; and 2 surveys administered to all 17 faculties of medicine. The gaps identified from the focused literature review and the results of the environmental scan will be used to develop the task force’s recommendations for action, highlighting the role of key partners in implementation and needed action.

Conclusion

The work of the task force provides an opportunity to bring the various partners together in a coordinated way. By understanding who is responsible and the actions each stakeholder needs to take to make the recommendations a reality, the task force can lay the groundwork for developing a coordinated, comprehensive health human resource strategy that considers the integral role of medical education as a health system intervention.

Résumé

Objectif

Élaborer une feuille de route pour la formation rurale dans le but de faire progresser le recrutement et le maintien en poste de médecins de famille dans les régions rurales, éloignées et isolées du Canada afin d’améliorer l’accès aux soins et les résultats sur le plan de la santé pour ces populations.

Composition du groupe de travail

Les membres du groupe de travail ont été choisis parmi des intervenants clés comme des enseignants, des professionnels de la santé, des présidents de comités sur l’éducation du Collège des médecins de famille du Canada, des doyens, des directeurs de départements de médecine familiale, des experts en éducation rurale et des décideurs concernés. C’est à dessein que les membres du groupe de travail ont été sélectionnés pour représenter une diversité de points de vue importants afin de veiller à ce que les travaux produits soient rigoureux et de grande qualité. Des observateurs de l’Association médicale canadienne et du Comité sur l’effectif en santé de Santé Canada ainsi que des représentants du Collège royal des médecins et chirurgiens du Canada ont aussi invités à exprimer leurs opinions et pour favoriser et coordonner un plan d’action impliquant de multiples organisations.

Méthodes

Le groupe de travail a commandé une recherche documentaire ciblée dans les publications révisées par des pairs et la littérature grise pour examiner la situation de la médecine rurale sur les plans de l’éducation, de la formation et de la pratique par rapport aux besoins des communautés rurales et éloignées au Canada sur le plan de la santé. Le groupe a aussi effectué une analyse environnementale.

Rapport

L’analyse environnementale comportait des entrevues avec plus de 100 décideurs, représentants gouvernementaux, médecins, enseignants, apprenants et dirigeants de communauté; 17 entrevues avec des médecins en pratique rurale; et 2 sondages auprès des 17 facultés de médecine. Les lacunes cernées dans la recherche documentaire ciblée et les résultats de l’analyse environnementale serviront à élaborer les recommandations du groupe de travail sur la marche à suivre, mettant en évidence le rôle des partenaires clés dans leur mise en œuvre et les mesures à prendre.

Conclusion

Les travaux du groupe de travail donnent la possibilité de rassembler divers partenaires de manière coordonnée. En comprenant les responsabilités à assumer et les mesures à prendre par chaque intervenant pour que se concrétisent les recommandations, le groupe de travail peut établir l’assise nécessaire pour élaborer une stratégie coordonnée et exhaustive en matière de ressources humaines qui tienne compte du rôle essentiel que joue l’éducation médicale comme intervention dans le système de santé.

About 18% of Canadians live in rural, remote, or isolated communities.1 Factors such as isolation from urban centres, poor weather conditions impairing access to remote locations, and lack of communication technology infrastructure have made it challenging for the Canadian health system to sustain equitable provision of health care services to these communities.2 The implications of this are evident when comparing the health of rural Canadians with that of their urban counterparts. There are higher incidences of poor nutrition, chronic disease, injury, and death among rural populations than among urban populations.3 These health differences are even more pronounced for indigenous populations in rural and remote communities that have experienced more difficulty in accessing regular primary care services.4 In fact, a call to action was highlighted in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission report, stating that indigenous health will not improve without considerable system change, given the persistent inequity and inaction across the health system.5 Despite the federal government’s investment in public health and community care, rural and remote populations in Canada continue to experience poor health.3,6

These health disparities are driven in part by the ongoing challenge of family physician shortages in rural and remote Canada. Although family physicians represent 50% to 53% of the physician work force, only 14% work in rural and remote communities.7 Rural communities experience a number of challenges in recruiting and retaining physicians, such as concerns regarding isolation, limited resources and health facilities, and the lack of educational and employment opportunities for physicians’ families.2

There are a number of policy measures that have been taken to address this challenge, including incentives for physicians to practise in rural and remote communities,8 increases in health human resources in the form of nurse practitioners and physician assistants, and investment in telehealth technology to facilitate communication in remote communities. One of the most prominent national and international strategies to address this health human resource challenge has been return-for-service funding and other financial incentives (bursaries, awards, scholarships, etc). However, according to a recent review from Australia, financial incentives have not resulted in adequate progress in addressing the physician resource gap experienced in rural and remote communities.9 Thus, despite some progress being made in indicators of patient care and health outcomes,10,11 rural health disparities and the closely linked challenge of recruiting and retaining rural family physicians to deliver high-quality care in these communities continue to persist.

Education as a health system intervention

Family physicians are a critical resource to rural and remote communities. In practising full-scope, comprehensive family medicine, family physicians often provide needed care services in the absence of other specialists who would traditionally deliver such care (eg, general surgery, general anesthesia). Family physicians adapt and evolve the family medicine competencies achieved while in residency training to meet community needs when they have established their clinical practices. Family medicine learners are provided comprehensive learning experiences to support the acquisition of generalist skills within the newly implemented Triple C Competency-based Curriculum.12 When learning is offered in rural environments family medicine residents are able to learn and acquire generalist competencies within a rural context. Exposing learners to rural contexts early and often while in medical school and residency gives them a better understanding of the opportunities and realities of rural practice. Exposure to rural practice by rural clinical teachers positively influences recruitment and retention of family physicians in rural and remote Canada.13

Currently, there are more than 160 rural-based family medicine clinical teaching sites, 75 of which focus primarily on the provision of longitudinal learning in rural and remote communities.14 However, further support for distributed medical education delivery is needed in order for rural medical education to serve as a comprehensive, coordinated health human resource strategy that can enhance the recruitment and retention of rural physicians.

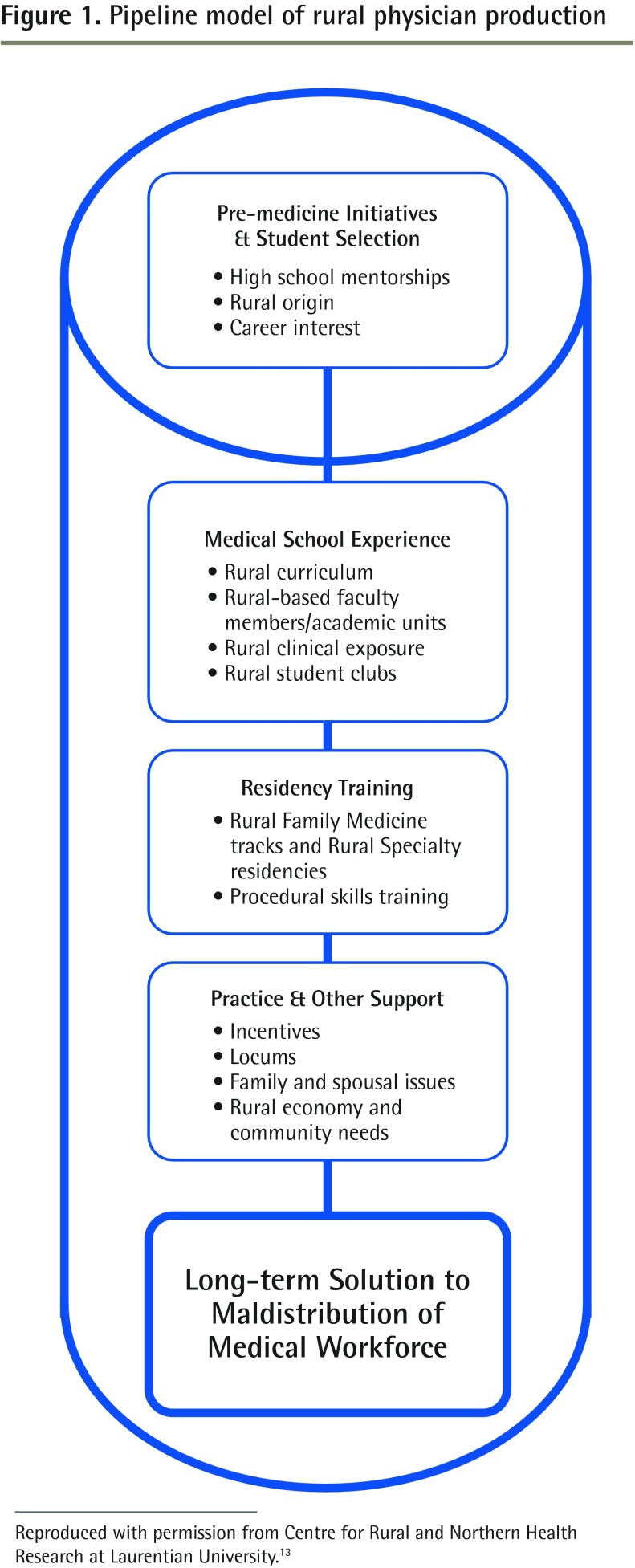

Pong and Heng’s rural education “pipeline” (Figure 1) is one model that describes how medical education can support the recruitment and retention of rural physicians by highlighting a mechanism for selecting, supporting, educating, and producing physicians for practice in rural communities in Canada.13 The model demonstrates how the pipeline for producing a rural physician begins before entry into medical school and continues throughout the medical education continuum through to practice. It is supported by evidence documenting that students from rural backgrounds are more likely to practise in rural communities than those from urban backgrounds, and that increased exposure to rural communities during the course of medical training enhances the likelihood that students will practise in rural and remote contexts.15

Figure 1.

Pipeline model of rural physician production

Reproduced with permission from Centre for Rural and Northern Health Research at Laurentian University.13

Pong and Heng identify 4 critical factors that can affect a physician’s decision to practise rural and remote medicine: rural upbringing, positive undergraduate rural exposure, targeted postgraduate exposure outside urban areas, and stated intent to practise or preference for family medicine or generalist practice.13,15 These factors, in combination with the pipeline approach to medical education delivery, provide a starting point for understanding how medical education programs must be structured to foster interest in practising rural family medicine. Some strategies for the delivery of comprehensive, coordinated rural education include targeted admission of students with rural backgrounds, integration of rural medicine into undergraduate and postgraduate curricula, efforts to ensure that rural learning experiences are positive for students, delineation of rural family medicine streams in postgraduate training, and increased coordination of education with recruitment and retention efforts in rural communities.14 However, rural and remote clinical teaching sites and teachers often have limited resources to train and graduate family physicians who are equipped with the skills needed to meet community needs. Support and coordination from higher organizational levels for implementation of these strategies remains a challenge.

Advancing Rural Family Medicine: The Canadian Collaborative Taskforce

Action to improve health care outcomes and access to primary care in rural and remote communities through a comprehensive, coordinated approach in Canada is required. Recognizing this need, the College of Family Physicians of Canada (CFPC) and the Society of Rural Physicians of Canada (SRPC) have come together to form Advancing Rural Family Medicine: The Canadian Collaborative Taskforce. The task force aims to advance the recruitment and retention of family physicians in rural, remote, and isolated regions of Canada in order to improve access and health care outcomes for these populations. The task force’s mandate is to develop a pan-Canadian rural education road map that will describe how this goal can be achieved. The road map will include a series of recommendations to enhance undergraduate, postgraduate, and continuing medical education training, with the aim of increasing the proportion of learners choosing rural family medicine practice as a lifelong career. In developing this road map, the task force will engage key stakeholders, including rural communities and all levels of government, in an effort to build the support and momentum needed for the recommendations to be implemented and put into action.

Composition of the task force

Members of the task force were chosen jointly by the CFPC and the SRPC from key stakeholder groups including educators, practitioners, CFPC education committee chairs, deans, chairs of family medicine, experts in rural education, and key decision makers. The task force members were also purposefully selected to represent a mix of key perspectives needed to ensure the work produced was rigorous and of high quality (Box 1).

Box 1. Perspectives selected for representation on the task force.

Representatives on the task force were selected jointly by the SRPC and the CFPC. The types of individuals needed are described below. The list was intended to help the executives of both organizations consider the mix of perspectives needed around that table in order for the work of the task force to be of high quality and to be strategic in nature, with key individuals of influence included.

Faculty with extended history of rural family medicine, advocacy, education, practice, administration, and policy

Representative with extensive knowledge of rural medicine family medicine programs and administration

Representative with extensive knowledge of family medicine and rural medicine within the university sector and of negotiating with governments for resource allocations

Representative with knowledge of rural medical education research data

Representative with distributed medical education experience and longitudinal clerkship experience at the medical school level

Early career rural and remote practitioner involved in CPD and mentorship programs

Representative with experience working at all levels of government: negotiations related to family practice in rural communities, physician education, and the physician work force, including knowledge of political issues and experience addressing the needs of rural educators and rural practitioners

Representative with an understanding of the needs of aboriginal communities and who is a strong advocate for teaching the domain in medical education

Representative with an understanding of accreditation processes at the CFPC and other education policy issues

Representatives chosen selectively from the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada, the Collège des médecins du Québec, the Indigenous Physicians Association of Canada, the Medical Council of Canada, the Federation of Medical Regulatory Authorities of Canada, and Health Canada’s Council on Health Workforce

CFPC—College of Family Physicians of Canada, CPD—continuing professional development, SRPC—Society of Rural Physicians of Canada.

Leaders in rural medical education and training across Canada were selected and invited to join the task force by the CFPC and the SRPC executives (Box 2). Observers from the Canadian Medical Association and Health Canada’s Council on Health Workforce, and representatives from the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada, were also invited to provide their perspectives on the task force’s work and to encourage and coordinate multiorganization action on implementing the recommendations to enhance recruitment and retention of rural family physicians.

Box 2. Task force membership.

Executive

Dr C. Ruth Wilson (Co-chair)

Dr Trina Larsen Soles (Co-chair)

Dr Braam De Klerk

Dr Kathy Lawrence

Dr Francine Lemire

Dr John Soles

Members

Dr Stefan Grzybowski

Dr Darlene Kitty

Dr Jill Konkin

Dr Roger Strasser

Rachel Munday (Society of Rural Physicians of Canada public member)

Dr Colin Newman

Dr Alain Papineau

Dr Tom Smith-Windsor

Dr Karl Stobbe

Dr Jim Rourke

Dr Jennifer Hall (ex officio, College of Family Physicians of Canada)

Mr Paul Clarke (Council on Health Workforce, Health Canada observer)

Dr Ken Harris (Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada representative)

Dr Granger Avery (Canadian Medical Association observer)

Methods

As part of its work, the task force commissioned a focused literature review, published in January 2016, entitled a Review of Family Medicine Within Rural and Remote Canada: Education, Practice, and Policy.14 This review included both peer-reviewed and gray literature to examine the status of rural medical education, training, and practice in relation to the health needs of rural and remote communities in Canada. The background paper provides a partial overview of the state of rural training and practice at the education and health systems levels and their effect on the family physician work force in rural communities. The document also captures gaps where further action is required.

An environmental scan was also completed to deepen the task force’s understanding of the state of family medicine education and practice in rural and remote communities. This scan included 3 components: federal, provincial, and territorial; rural medical education; and rural physician.

Federal, provincial, and territorial scan: Interviews with more than 100 policy makers, government representatives, providers, educators, learners, and community leaders were conducted to understand successes and challenges with recruitment and retention policy initiatives.

Rural medical education scan: Two surveys (Rural and Remote Undergraduate Medical Education Survey, Postgraduate Medical Education Survey) were administered to all 17 faculties of medicine to document rural education being delivered and to identify challenges, barriers, and successes experienced across the faculties of medicine and their affiliated family medicine residency programs.

Rural physician scan: Seventeen interviews with practising rural family physicians were conducted to identify the factors critical to recruitment and retention from the perspectives of those engaged in delivering care in rural and remote contexts.

The gaps identified from the focused literature review and the results of the environmental scan will be used to develop the task force’s recommendations for action, highlighting the role of key partners in implementation and needed action.

Social accountability framework: Pentagram Partners

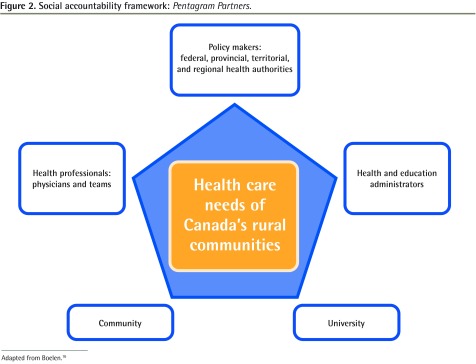

Although enhancing rural medical education and training is critical, it is only one part of the solution for addressing the health care challenges in rural and remote Canada. There is a concerted effort needed on the part of national and provincial stakeholders to support evidence-informed physician resource planning, to provide support for the medical education system, and to collaborate in developing an integrated strategy to allocate resources for rural and remote health. Thus, support for rural medical education training requires coordinated efforts and collaboration between multistakeholder partners including rural communities, policy makers, rural health professionals and physicians, universities, and health education administrators (Figure 2).16 These “Pentagram Partners” are critical players in upholding the social accountability mandate to provide high-quality care to those living in rural and remote Canada.

Figure 2.

Social accountability framework: Pentagram Partners.

Adapted from Boelen.16

Collaboration and coordination among the partners in the social accountability framework will be critical to the work of the task force. Despite the many efforts made to advance rural health care delivery and the progress that has been seen in rural medical education programs, much more remains to be done. In developing the recommendations, the task force will make a concerted effort to engage these partners in identifying how to implement them. The recommendations will undergo a stakeholder consultation process to delineate each stakeholder’s role in achieving the goal of high-quality health care delivery in rural and remote communities in Canada.

Each of these partners has a key role to play in advancing recruitment and retention initiatives, and the work of the task force provides an opportunity to bring these partners together in a coordinated way. The task force will explore the roles of medical education, rural communities, and policy makers in advancing the health of those living in rural and remote contexts. By understanding who is responsible and the actions each stakeholder needs to take to make the recommendations a reality, the task force can lay the groundwork for developing a coordinated, comprehensive health human resource strategy that considers the integral role of medical education as a health system intervention. For more information and additional resources, visit www.cfpc.ca/arfm.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS

The Canadian health system faces a variety of challenges to sustaining equitable provision of health care services for the roughly 18% of Canadians who live in rural, remote, or isolated communities, and their health outcomes are poorer as a result. These health disparities are driven in part by ongoing shortages of family physicians in rural and remote Canada.

Recognizing the need for a comprehensive, coordinated approach to improving recruitment and retention of family physicians in these regions, the College of Family Physicians of Canada and the Society of Rural Physicians of Canada came together to form Advancing Rural Family Medicine: The Canadian Collaborative Taskforce.

A literature review and environmental scan have helped to understand the current state of family medicine education and practice in rural and remote communities. The task force will explore the roles of medical education, rural communities, and policy makers in advancing the health of those living in rural and remote contexts.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR

Le système de santé canadien est confronté à divers défis pour maintenir une prestation équitable de services de santé aux quelque 18 % de Canadiens qui vivent dans des communautés rurales, éloignées ou isolées, et conséquemment, leurs résultats en matière de santé sont moins bons. Ces disparités sur le plan de la santé sont attribuables en partie aux pénuries constantes de médecins de famille dans le Canada rural et éloigné.

Reconnaissant la nécessité d’adopter une approche complète et coordonnée pour améliorer le recrutement et le maintien en poste de médecins de famille dans ces régions, le Collège des médecins de famille du Canada et la Société de la médecine rurale du Canada se sont réunis pour former Faire avancer la médecine familiale rurale : Groupe de travail collaboratif canadien.

Une recherche documentaire et une évaluation environnementale ont contribué à mieux faire comprendre la situation actuelle sur les plans de la formation et de la pratique en médecine familiale dans les communautés rurales et éloignées. Le groupe de travail examinera les rôles de la formation médicale, des communautés rurales et des décideurs pour favoriser la santé de ceux qui vivent dans des contextes ruraux et éloignés.

Footnotes

This report is copublished in the Winter 2017 issue of the Canadian Journal of Rural Medicine.

Contributors

The authors are Co-chairs of Advancing Rural Family Medicine: The Canadian Collaborative Taskforce and both contributed to preparing the manuscript for publication on behalf of the task force.

Competing interests

None declared

References

- 1.Canadian Institute for Health Information. Supply, distribution and migration of Canadian physicians, 2012. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. Quality through collaboration. The future of rural health. Committee on the Future of Rural Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herbert R. Canada’s health care challenge: recognizing and addressing the health needs of rural Canadians. Lethbridge Undergrad Res J. 2007;2(1) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Canadian Institute for Health Information. Disparities in primary health care experiences among Canadians with ambulatory care sensitive conditions. Analysis in Brief. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Honouring the truth, reconciling for the future: summary of the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Winnipeg, MB: Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lavergne MR, Kephart G. Examining variations in health within rural Canada. Rural Remote Health. 2012;12:1848. Epub 2012 Feb 29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Canadian Institute for Health Information. Physicians Canada, 2013: summary report. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mitton C, Dionne F, Masucci L, Wong S, Law S. Innovations in health service organization and delivery in northern rural and remote regions: a review of the literature. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2011;70(5):460–72. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v70i5.17859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duckett S, Breadon P, Ginnivan L. Access all areas: new solutions for GP shortages in rural Australia. Melbourne, Aust: Grattan Institute; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tiepoh M, Reimer B. Global influences on rural and urban disparity differences in Canada: policy implications for improving rural capacity. Discussion paper for the NRE annual spring workshop. Montreal, QC: New Rural Economy Project, Concordia University; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Halseth G, Ryser L. Trends in service delivery: examples from rural and small town Canada, 1998 to 2005. J Rural Community Dev. 2006;1(2):69–90. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oandasan I, Saucier D, editors. Triple C competency-based curriculum report—part 2: advancing implementation. Mississauga, ON: College of Family Physicians of Canada; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pong RW, Heng D. The link between rural medical education and rural medical practice location: literature review and synthesis. Sudbury, ON: Centre for Rural and Northern Health Research, Laurentian University; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bosco C, Oandasan I. Review of family medicine within rural and remote Canada: education, practice, and policy. Mississauga, ON: College of Family Physicians of Canada; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strasser R, Neusy AJ. Context counts: training health workers in and for rural and remote areas. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88(10):777–82. doi: 10.2471/BLT.09.072462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boelen C. Building a socially accountable health professions school: towards unity for health. Educ Health (Abingdon) 2004;17(2):223–31. doi: 10.1080/13576280410001711049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]