Coming together is a beginning; keeping together is progress; working together is success.

Henry Ford

Engagement in research has been shown to enhance the ability of individuals and communities to address their own health needs and health disparity issues while ensuring that researchers understand the priorities of individuals and communities.1,2 However, everyday researchers with limited understanding of and experience with effective methods and tools of engagement write and submit proposals that would benefit from engaging patients and communities. Furthermore, guidance that is available for peer-review panels on evaluating research proposals that engage patients and communities has not been systematically applied.3

Patients and communities do not necessarily need to be involved in all aspects of the research process; however, their involvement affords academic researchers more specific and relevant research questions, contextual interpretation, and knowledge translation in and with the community. We have had experience cocreating various elements of the research process with patients and communities.2,4–9 The Canadian Institutes of Health Research has been supporting full engagement with the inclusion of knowledge users who are patients or community members as co-investigators (equal partners) on implementation and translational research endeavours.10

In Canada, the framework for engaging patients and communities is clearly outlined in the 2014 Tri-Council policy statement, which includes a chapter that focuses on working with aboriginal communities.11 The approach outlined in this policy statement can and should be adapted more broadly when considering patient and community engagement. As identified by Jagosh and colleagues,2 engagement leads to improved community well-being; therefore, services and systems need to support the investment necessary to make this a reality.

This article aims to provide some practical tips and guidance for the peer-review process and the evaluation of grant proposals in which patients and communities are engaged. These tips have been designed to assist patients and communities, community-academic research teams, and reviewers of grant proposals to clarify the extent to which the process of engagement has been authentic and robust.

Considerations for the peer-review process

Butler and Greenhalgh12 indicate that contemporary approaches to patient and community engagement involve codesign, coproduction, coleadership, and mutual learning, frequently within a systems model.12,13 The principles espoused are found within the constructs of participatory health research.14 As part of community engagement, the experiences and knowledge of patients and communities are important, as they provide learning for researchers and health care providers, as well as help policy makers to make decisions about treatment or management.12 Relationships are key in codesign, coproduction, coleadership, and mutual learning. Individuals and communities need to be engaged in the process over time in order to develop sustainable, mutually respectful, and trusting relationships before asking or systematically answering relevant questions.12,15–19

Peer review is a thoughtful critique by peers—1 or more people with competencies similar to those of the authors of the work being reviewed. When reviewing proposals that purport to engage patients and communities, we suggest that reviewers consider the following questions.

Are patients and communities equitably involved in all appropriate aspects of designing the proposal?

Is there coproduction of the processes to be used during and throughout the research proposed?

Are patients and community members named as investigators (and is there a description of past collaborations with the patients or community) or are they considered members of the leadership team?

How are patients or communities involved in analysis and interpretation of results, in dissemination of findings through presentations, and as co-authors?

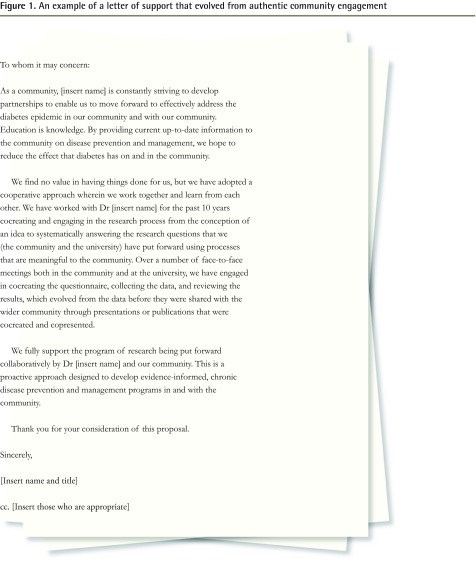

Letters of support from the patients or communities being engaged should clearly describe the following: the relationship with the research team; the origin of the research questions or study topic; the role of the patient or community in defining the goals, objectives, and research questions; and plans for interpretation of findings and ongoing participation including dissemination, which includes the importance of the research from the perspective of patients or the community. In addition to this, the research team should describe meetings and other events convened to engage patients or communities in the planning of the research project.20 Figure 1 presents an example of a letter of support that evolved from authentic community engagement. This letter is by no means a template, but it serves as an example of a letter of support that was developed with a community in response to clarifying its authentic engagement. In contrast, a letter that only states, for example, “… support for the research proposal of Drs [insert names] is a priority in our community” might be considered token involvement and not authentic engagement.

Figure 1.

An example of a letter of support that evolved from authentic community engagement

The peer-review system is designed to ensure accountability not only to the funding sources, but also to the patients and communities. Therefore, patients and community members should be complementing the scientific expertise of researchers and be reviewing grant applications for patient or community relevance. In many communities, there are people who are familiar with research methods and who are knowledgeable in reviewing grant applications from their own perspective. To increase patient or community capacity to participate in reviewing project submissions, training and educational opportunities are essential, and might include engagement strategies such as boot camp translation, which was developed and tested by patients in the High Plains Research Network9 in Colorado. During boot camp translation, community members and researchers work together to devise appropriate communication strategies for intervention-related messages that fit the community’s needs.

Conclusion

As we move toward authentic engagement within the research process, grant applications should describe the elements that have been or will be undertaken collaboratively. Letters of support should clearly describe the relationship between the patients or communities and the research team. Thus, grant applications should be reviewed by patients or communities and researchers.

Hypothesis is a quarterly series in Canadian Family Physician, coordinated by the Section of Researchers of the College of Family Physicians of Canada. The goal is to explore clinically relevant research concepts for all CFP readers. Submissions are invited from researchers and nonresearchers. Ideas or submissions can be submitted online at http://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/cfp or through the CFP website www.cfp.ca under “Authors and Reviewers.”

Footnotes

Competing interests

All authors are members of the Participatory Research in Primary Care Working Group of the North American Primary Care Research Group.

References

- 1.Clinical and Translational Science Awards Community Engagement Key Function Committee Task Force . Principles of community engagement. Publication no. 11-7782. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: National Institute of Health; 2011. Available from: www.atsdr.cdc.gov/communityengagement/pdf/PCE_Report_508_FINAL.pdf. Accessed 2016 Nov 28. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jagosh J, Macaulay AC, Pluye P, Salsberg J, Bush PL, Henderson J, et al. Uncovering the benefits of participatory research: implications of a realist review for health research and practice. Milbank Q. 2012;90(2):311–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2012.00665.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mercer SL, Green LW, Cargo M, Potter MA, Daniel M, Olds RS, et al. Reliability-tested guidelines for assessing participatory research projects. In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-based participatory research for health: from process to outcomes. 2nd ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 2008. pp. 407–18. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jackson CL, Greenhalgh T. Co-creation: a new approach to optimising research impact? Med J Aust. 2015;203(7):283–4. doi: 10.5694/mja15.00219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Macaulay AC, Commanda LE, Freeman WL, Gibson N, McCabe ML, Robbins CM, et al. Participatory research maximises community and lay involvement. North American Primary Care Research Group. BMJ. 1999;319(7212):774–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7212.774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Macaulay AC, Paradis G, Potvin L, Cross EJ, Saad-Haddad C, McComber A, et al. The Kahnawake Schools Diabetes Prevention Project: intervention, evaluation, and baseline results of a diabetes primary prevention program with a Native community in Canada. Prev Med. 1997;26(6):779–90. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1997.0241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramsden VR, McKay S, Crowe J. The pursuit of excellence: engaging the community in participatory health research. Glob Health Promot. 2010;17(4):32–42. doi: 10.1177/1757975910383929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martin RE, Chan R, Torikka L, Granger-Brown A, Ramsden VR. Healing fostered by research. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54:244–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Norman N, Bennett C, Cowart S, Felzien M, Flores M, Flores R, et al. Boot camp translation: a method for building a community of solution. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013;26(3):254–63. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2013.03.120253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Canadian Institutes of Health Research [website] Knowledge user engagement. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Institutes of Health Research; 2016. Available from: www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/49505.html. Accessed 2016 Nov 29. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada. Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada . Tri-Council policy statement. Ethical conduct for research involving humans. Ottawa, ON: Government of Canada; 2014. Available from: www.pre.ethics.gc.ca/pdf/eng/tcps2-2014/TCPS_2_FINAL_Web.pdf. Accessed 2016 Nov 29. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Butler C, Greenhalgh T. What is already known about involving users in service transformation? In: Greenhalgh T, Humphrey C, Woodard F, editors. User involvement in health care. London, UK: Wiley-Blackwell; 2011. pp. 10–27. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilson E, Taylor G, Phillips S, Stewart PJ, Dickinson G, Ramsden VR, et al. CMAJ. 2001;164(13):1853–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.International Collaboration for Participatory Health Research [website] What is participatory health research (PHR)? Berlin, Ger: International Collaboration for Participatory Health Research; Available from: www.icphr.org/. Accessed 2016 Jan 30. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mezirow J. Fostering critical reflection in adulthood: a guide to transformative and emancipatory learning. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 1990. and associates. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mezirow J. Learning as transformation: critical perspectives on a theory in progress. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 2000. and associates. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramsden VR, Integrated Primary Health Services Model Research Team Learning with the community. Evolution to transformative action research. Can Fam Physician. 2003;49:195–7. (Eng), 200–2 (Fr). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kahnawake Schools Diabetes Prevention Project . Code of research ethics. Kahnawake, QC: Kahnawake Schools Diabetes Prevention Project; 2007. Available from: http://ksdpp.org/media/ksdpp_code_of_research_ethics2007.pdf. Accessed 2016 Jan 30. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Torjesen I. Public involvement in research should be “second nature” by 2025, review concludes. BMJ. 2015;350:h1913. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute . Engagement rubric for applicants. Washington, DC: Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute; 2016. Available from: www.pcori.org/sites/default/files/Engagement-Rubric.pdf. Accessed 2016 Jan 30. [Google Scholar]