Abstract

Objective

To examine FPs’ training needs for conducting decision-making capacity assessments (DMCAs) and to determine how training materials, based on a DMCA model, can be adapted for use by FPs.

Design

A scoping review of the literature and qualitative research methodology (focus groups and structured interviews).

Setting

Edmonton, Alta.

Participants

Nine FPs, who practised in various settings, who chose to attend a focus group on DMCAs.

Methods

A scoping review of the literature to examine the current status of physician education regarding assessment of decision-making capacity, and a focus group and interviews with FPs to ascertain the educational needs of FPs in this area.

Main findings

Based on the scoping review of the literature, 4 main themes emerged: increasing saliency of DMCAs owing to an aging population, suboptimal DMCA training for physicians, inconsistent approaches to DMCA, and tension between autonomy and protection. The findings of the focus groups and interviews indicate that, while FPs working as independent practitioners or with interprofessional teams are motivated to engage in DMCAs and use the DMCA model for those assessments, several factors impede their conducting DMCAs. The most notable barriers were a lack of education, isolation from interprofessional teams, uneasiness around managing conflict with families, fear of liability, and concerns regarding remuneration.

Conclusion

This pilot study has helped to inform ways to better train and support FPs in conducting DMCAs. Family physicians are well positioned, with proper training, to effectively conduct DMCAs. To engage FPs in the process, however, the barriers should be addressed.

Résumé

Objectif

Déterminer le type de formation dont les médecins ont besoin pour évaluer la capacité de prendre des décisions (ECPD) et déterminer comment les outils de formation, fondés sur un modèle d’ECPD, peuvent être adaptés en vue d’une utilisation par les médecins de famille.

Type d’étude

Une revue extensive de la littérature et une méthodologie de recherche qualitative (groupes de discussion et entrevues structurées).

Contexte

Edmonton, Alberta.

Participants

Neuf MF pratiquant dans divers contextes, qui ont accepté de participer à un groupe de discussion sur l’ECPD.

Méthode

Une revue extensive de la littérature afin d’étudier l’état actuel de la formation des médecins sur l’évaluation de la capacité de prendre des décisions, et un groupe de discussion et des entrevues avec des MF pour établir les besoins de formation dans ce domaine.

Principales observations

L’examen de la littérature a fait ressortir 4 thèmes principaux : l’ECPD est maintenant plus pertinente en raison du vieillissement de la population; la formation des médecins est sous-optimale en ce domaine; les méthodes d’ECPD varient; et l’autonomie du patient et sa protection sont souvent en conflit. Les observations des groupes de discussion et des entrevues donnent à penser que les MF sont intéressés à effectuer des ECPD en utilisant le modèle proposé, et ce, qu’ils pratiquent en solo ou au sein d’équipes interprofessionnelles. Toutefois, plusieurs obstacles les empêchent de le faire, les plus importants étant le manque de formation, l’absence de rapports avec une équipe interprofessionnelle, la difficile gestion des conflits avec les familles, les éventuels problèmes de responsabilité et certaines inquiétudes concernant la rémunération.

Conclusion

Cette étude pilote nous fait mieux connaître les façons d’assurer une meilleure formation et un meilleur soutien aux MF lorsqu’ils effectuent des ECPD. Avec une formation adéquate, les médecins de familles seront bien placés pour le faire. Il faudra toutefois s’occuper des obstacles mentionnés si on veut qu’ils s’y engagent.

A person’s capacity to make personal or financial decisions is an important component of independence.1 Adults with developmental disabilities or psychiatric and cognitive disorders can face challenges to their autonomy.2,3 The degree of impairment of mental capacity can vary as a result of disease processes.4–7 As the prevalence of persons 65 years and older rises, so does the incidence of dementia.8–13 It is anticipated that an increasing number of individuals will experience a decline in their decision-making capacity (DMC). Thus, assessment of DMC emerges as an important issue14–17 that has evoked legal and ethical debate worldwide.14

Legislation that guides assessment of DMC varies provincially and nationally. According to the World Health Organization, legislation should “recognize and protect the right to appropriate autonomy and self-determination,”18 and ensure “free and informed consent to treatment, supported decision-making, and procedures for implementing advance directives.”19 In the province of Alberta, several legislative acts ensure the least restrictive and intrusive outcomes around DMC, including the Personal Directive Act20 and the Powers of Attorney Act,21 which allow adults to establish personal directives or enduring power of attorney and appoint agents who make decisions on their behalf. The Adult Guardianship and Trusteeship Act22 provides a range of options for decision making in the absence of a personal directive (personal affairs) or enduring power of attorney (financial affairs). These acts define capacity as the ability of a person to understand the information that is relevant to making a personal decision in a specific domain and to appreciate the reasonable foreseeable consequences of the decision.20

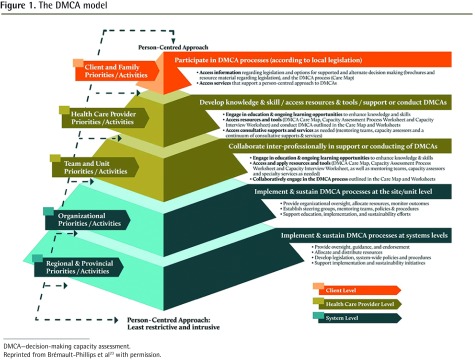

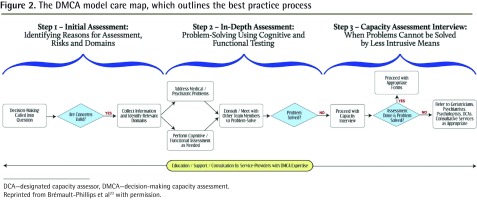

A decision-making capacity assessment (DMCA) is an assessment of varying degrees of complexity conducted by health care professionals (HCPs) to determine whether there is sufficient evidence to declare a person incapable of managing his or her affairs.20 A DMCA model was developed in Alberta consisting of a person-centred best practice process at the client level to assess DMCAs, and implementation strategies at the system and HCP levels to enhance the ability of practitioners, interprofessional teams, and organizations to provide DMCAs (Figures 1 and 2).23,24

Figure 1.

The DMCA model

DMCA—decision-making capacity assessment.

Reprinted from Brémault-Phillips et al23 with permission.

Figure 2.

The DMCA model care map, which outlines the best practice process

DCA—designated capacity assessor, DMCA—decision-making capacity assessment.

Reprinted from Brémault-Phillips et al23 with permission.

Family physicians and DMCAs

Family physicians are recognized as assessors of DMC.20–22 Working independently or on interprofessional teams, FPs consider DMC as part of informed consent or other concerns. Owing to long-standing relationships and familiarity with patients, they are well positioned to determine medical stability, conduct DMCAs, and formulate opinions. While assessment of DMC is inherent in medical practice, there is no evidence that FPs feel confident to assess DMC. Although workshops regarding DMCAs and the model have been offered since 2006, participation among FPs has been low.24 Box 1 outlines the learning objectives of a DMCA workshop.

Box 1. Learning objectives of a DMCA workshop.

The participant will ...

acquire knowledge of the guiding principles in capacity assessment

appraise a capacity-assessment process

explore an interdisciplinary approach to capacity assessment

review capacity-assessment worksheets used in this process

apply the above information in assessment of capacity through case examples

DMCA—decision-making capacity assessment.

The purpose of this study was to examine FPs’ training needs for conducting DMCAs and to determine how training materials, based on a DMCA model, can be adapted for use by FPs. Given the ongoing developmental evaluation25 of the DMCA model, this is well aligned with the model’s evolution.24 Our goal is to use results from our scoping literature review and the focus groups to customize DMCA workshop materials and produce additional resources to support FPs. It is anticipated that better training in DMCA will translate to greater physician confidence and engagement in capacity assessments.

METHODS

Two methodologic approaches were used in this pilot study: a scoping review of the literature and qualitative methodology involving a focus group and in-person interviews.

Literature review

The literature was surveyed to explore DMCA in family practice and a scoping review was conducted regarding training for FPs in DMCAs. Methodology outlined by Arksey and O’Malley,26 as well as Levac and colleagues,27 guided the review. Along with the gray literature, the following 7 databases were identified and searched: MEDLINE; PsycINFO; Biomedical Reference Collection; CINAHL; Health Source: Nursing/Academic Edition; Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection; and iMediSearch. The inclusion criteria were studies that focused on DMCA, physicians or practitioners as the primary audience, and published in English between 2005 and 2015. Being an iterative process,27 the search strategy was refined by adding the search terms accommodation, finance, association, and legal. The bibliographies were hand searched for additional relevant articles.

Focus group and interviews

A focus group was held with 7 FPs. Participants self-selected to attend after receiving an e-mail from the Alberta Medical Association, the Alberta College of Family Physicians, the Edmonton Zone Medical Association, Alberta Health Services, or Covenant Health. Interviews with 2 physicians experienced in DMCA were later held to validate initial focus group findings. Focus group and interview questions captured demographic characteristics, practice details, and frequency of conducting DMCAs. Questions addressed participants’ opinions about their roles in the DMCA process, confidence regarding knowledge or expertise about legislation, use of a DMCA process, use of resources, and interprofessional team experience. (For a copy of the focus group questionnaire, please contact the corresponding author.) The focus group discussion and interviews were audiorecorded, transcribed, and entered into NVivo 10 software for coding and analysis by a trained qualitative researcher (B.S.). Member checking was conducted by research team members. Standardized coding techniques with an adapted version of Roper and Shapira’s approach was used to identify patterns and themes.28 Thematic analysis of the data and field notes was conducted until saturation was reached regarding barriers, facilitators, and recommendations. Conscious efforts were made to search for contradictory observations. The study received ethics approval from the University of Alberta Health Research Ethics Board Health Panel.

FINDINGS

Literature review

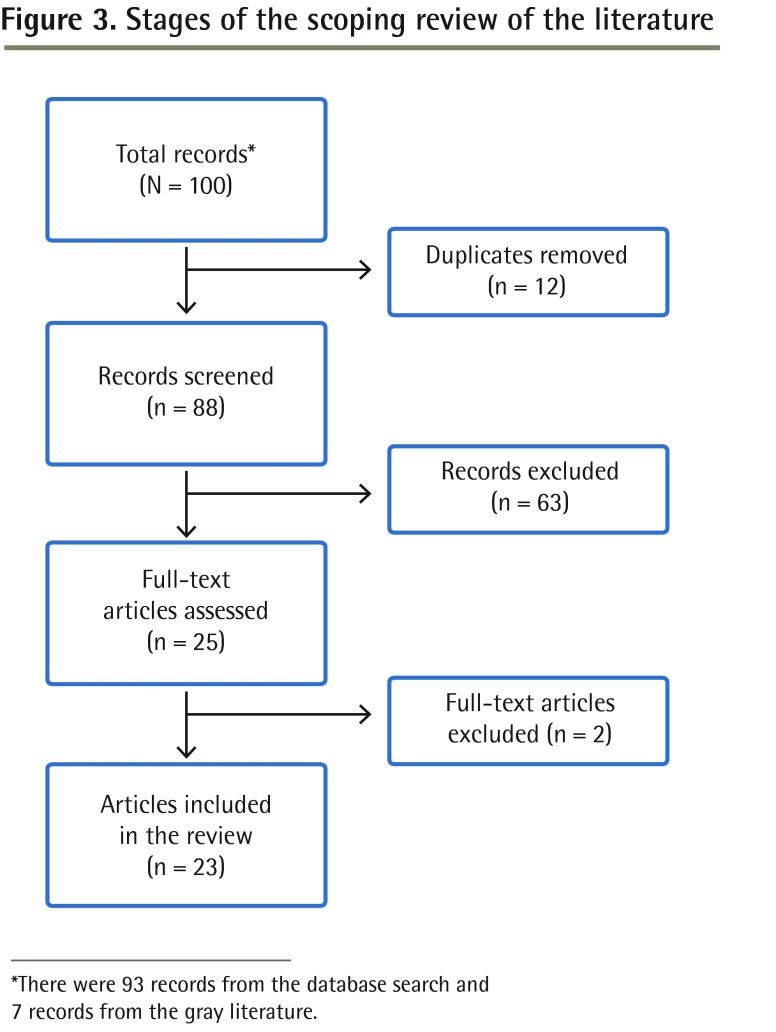

Of the 100 titles and abstracts (93 from databases, 7 from the gray literature), 25 sources were reviewed in full with 23 meeting the inclusion criteria (Figure 3). The literature review highlighted the paucity of information on DMCAs in family practice. Nevertheless, the following general themes emerged.

Figure 3.

Stages of the scoping review of the literature

*There were 93 records from the database search and 7 records from the gray literature.

Increasing saliency of DMCAs owing to an aging population

Approximately 40% of general hospital patients are seniors, 33% to 50% of whom have impaired DMC.29 As baby boomers age beyond 75 years, this number will surge.13,29 In one survey of Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine members, 90% of consultation psychiatrists indicated that at least 50% of DMCAs were performed on patients older than 60 years of age.30

Suboptimal DMCA training for physicians.

There is a lack of education in DMCA,29,31 leading to calls for compulsory training for physicians.14,18,32 It has also been shown that training can improve capacity assessment, with recommendations that physician training in DMCA should be commensurate with their training in geriatric syndromes.32–34 For example, fellowship-trained physicians received considerably more lectures and supervised cases than non–fellowship-trained physicians did, and they also provided higher ratings for their training than the non–fellowship-trained did.29 Non–fellowship-trained physicians were more likely to seek additional training on DMCAs.29 In a survey of 1087 physicians and HCPs in a medical and long-term care centre, 84% of respondents perceived assessment of DMC to be a moderate to very important area of practice, yet 75% reported minimal training and limited to moderate levels of knowledge on the topic.31 There have been numerous calls for compulsory DMCA training as part of the clinical education of physicians, psychologists, and other HCPs.14,18,32

Inconsistent approach to DMCA

While assessment tools29–31,35 and practice guidelines for DMCAs exist,36,37 most DMCAs are done on an ad hoc basis.38 Variation across regions and lack of uniform standards contribute to disagreement regarding DMCA outcomes.39 In a review of compliance with the UK Mental Capacity Act, most clinicians did not inquire about advance directives or powers of attorney, court-appointed guardians, or previous impaired DMC.40 Inconsistency in the approach to DMCA might lead to clinicians failing to identify patients who lack DMC.30,35 In one study, physicians recognized that patients were incapable of medical decisions in 42% of patients independently judged to lack capacity.35 Some question whether “judges, HCPs, and business people simply translate a specific numerical score on a standardized instrument into an automatic finding of competence or incompetence.”41

Tension between autonomy and protection

The field of DMC is dominated by tension between ethical principles of autonomy and protection.14 “Maintaining patient autonomy while protecting those potentially incapacitated”29 in specific domains of decision making35,42 is essential. While physicians make proxy medical decisions,30 in the contemporary context, patients have a right to make their own choices and are assumed to have DMC unless otherwise indicated. “Respect for autonomy is such that the principle of the sanctity of human life must yield to the principle of self-determination.”42 Family physicians working under this assumption can, however, mistake patient compliance with treatment recommendations for informed consent.40,43–45

Focus group and interviews

Study participants included 9 FPs (4 men and 5 women; mean age was 38). Mean practice experience was 9 years. Most of the FPs worked in Edmonton, Alta, or the surrounding area in primary care, day programs, home living, supportive living, long-term care, restorative care, a geriatric clinic, and a geriatric inpatient or rehabilitation units. Two participants were training in the care of the elderly program and 5 worked in geriatric settings. Frequency of conducting DMCAs varied (4 FPs conducted 0 to 1, 4 FPs conducted 2 to 3, and 1 FP conducted 5 to 10 DMCAs per month).

Data analysis revealed 3 factors that facilitated the use of the DMCA model (ie, commitment to person-centred care, a team-based approach to DMCAs, and the tools associated with the model), as well as 4 barriers to its use (ie, knowledge gaps; isolation from interprofessional teams; conflicts with families; and concerns about liability and responsibility to the patient, as well as lack of clarity regarding billing practices). These findings are presented in Table 1, with supporting quotations from the focus groups.

Table 1.

Themes and findings that emerged from the focus groups

| FACTORS | FINDINGS AND RELATED PARTICIPANT QUOTATIONS | THEMES FROM SCOPING LITERATURE REVIEW THAT THIS FACTOR APPLIES TO |

|---|---|---|

| Facilitators | ||

| • Physicians’ commitment to delivering PCC | As PCC is central to the DMCA model, many participants felt comfortable adopting it

|

DMCAs will become more important as the population ages. Providing PCC will involve the administration of DMCAs to those patients for whom DMC is a concern |

| • Team-based approach to conducting comprehensive DMCAs | A team-based approach is valuable in conducting comprehensive DMCAs. Physicians are often reliant on IP team members for assessment and problem-solving expertise. In units and sites that were able to establish a collaborative IP approach to DMCAs, physicians believed they were better able to conduct a comprehensive DMCA

|

Many doctors report that training is suboptimal. Doctors lack sufficient training to complete DMCAs on their own and rely greatly on other IP team members for expertise. There is no consistent approach to DMCA; physicians note that there is no method to conducting DMCAs, but note that working with an IP team is a good approach |

| • Tools associated with the DMCA model to guide the DMCA process | The DMCA model tools—in particular the worksheets—are reportedly key facilitators. Physicians appreciated that the worksheets guide the process, prompting them to cover all aspects of the DMCA. They also found that the worksheet facilitates collation of IP team findings and standardizes the problem-solving approach

|

Many doctors report that training is suboptimal. Doctors lack sufficient training, but note that the worksheets associated with the DMCA model process improves their ability to complete DMCAs |

| Barriers | ||

| • Knowledge gaps regarding DMCAs | More inexperienced FPs did not think they had enough training and exposure to real-life experiences to confidently conduct DMCAs. Some felt less confident making judgments when unfamiliar with a patient, while others were worried about the serious consequences of their assessment (eg, patient’s loss of autonomy)

|

Many doctors report that training is suboptimal and tension exists between ethical principles of autonomy and protection, particularly when unfamiliar with a patient |

| • Isolation from IP teams | Some participants reported that they did not have access to an IP team, felt uncomfortably isolated, and desired greater collaboration

|

Many doctors report that training is suboptimal. It is difficult to make clinical judgments concerning DMC when education is lacking and there is limited access to IP teams to assist |

| • Conflicts with families | Resolving conflicts with family members residing at a distance and infrequently involved in a patient’s life was difficult, as was balancing patient medical needs while engaging with family members. Physicians noted that conflicts tend to arise over issues such as medical decisions (eg, family attempting to override their medical judgment), finances, DMCAs, facility choice, end-of-life decisions, and legal guardianship), or when family members either appear to have ulterior motives (eg, financial) or are unaware of the patient’s wishes (eg, goals of care and advance directives)

|

Tension exists between ethical principles of autonomy and protection. When family members become involved, issues can arise concerning autonomy and familial wishes, regardless of motive |

| • Concerns about liability, responsibility to the patient, and lack of clarity on billing | Physicians are in a difficult position regarding DMCAs, as they often spend only short periods of time with a patient (participants reported conducting a DMCA in 0.5 to 2 hours), during which time they make a determination about a person’s DMC that might have legal implications

Knowledge gaps were evident regarding billing methods for DMCAs and financial remuneration outlined within and permissible according to local legislation

|

DMCAs will become more important as the population ages and many doctors report that training is suboptimal. There will be increasing demands on doctors as their patients age, requiring additional or increased training and time to complete these assessments |

DMC—decision-making capacity, DMCA—decision-making capacity assessment, IP—interprofessional, OT—occupational therapist, PCC—person-centred care, PT—physical therapist.

Participants offered a number of recommendations that might be of interest to others involved in medical education regarding enhancing education or training that might lead to facilitating better engagement in DMCAs. These recommendations included enhanced training and education, access to interprofessional teams, consultative or mentoring support, and remuneration (Table 2).

Table 2.

Participant recommendations for enhancing FP education and engagement

| RECOMMENDATIONS | FINDINGS AND PARTICIPANT QUOTATIONS | THEME FROM SCOPING LITERATURE REVIEW THAT THIS RECOMMENDATION APPLIES TO |

|---|---|---|

| Enhanced training and education is needed | Physicians emphasized the need for appropriate training to ensure that those conducting DMCAs have requisite knowledge and skills. Participants indicated that more experience working through case studies with physician colleagues would be beneficial

|

Many doctors report that training is suboptimal |

| Access to IP team supports holistic and comprehensive DMCA | Participants recommended having greater access to experienced HCPs (eg, social workers, OT, nurses) to facilitate or conduct DMCAs

|

Many doctors report that training is suboptimal |

| Consultative or mentoring support would enable FPs to enhance their competencies in DMCAs and discuss complex cases with colleagues | Participants expressed the need for access to physician colleagues who might be able to offer consultative or mentoring support

|

Many doctors report that training is suboptimal |

| Appropriate remuneration is needed for services rendered | Greater clarity regarding billing practices and remuneration processes was recommended. Participants suggested that this might increase the number of physicians who would engage in DMCAs

|

DMCAs will become more important as the population ages. To be agreeable with completing DMCAs, physicians need to be appropriately remunerated through established payment and billing procedures |

ARP—alternate relationship plan, DMCA—decision-making capacity assessment, EPOA—enduring power of attorney, HCP—health care professional, IP—interprofessional, OT—occupational therapist, PT—physical therapist, RN—registered nurse.

DISCUSSION

An aging population and increases in the number of individuals with dementia13 will result in an increase in the demand for DMCAs.8–17,29,30 Information gathered from our scoping literature review and qualitative findings indicated that training for DMCA is suboptimal. Currently, the need for a consistent approach to DMCAs is paramount, considering the ethical repercussion of autonomy versus protection. Participants noted that more education was required for DMCAs and that education and training should focus on person-centred care, a team-based approach, and available tools to guide the use of the DMCA model. With education and training, the barriers to DMCAs can be removed.14,18,19,32–34

Participants in the focus groups and interviews agreed that education and training was critical for enabling them to effectively and confidently conduct DMCAs, an opinion that aligned with the findings in the literature review.10,14,18,29,31–35 The World Health Organization emphasizes “education and support ... should be an essential part of capacity-building for all involved in providing dementia care.”18 Efforts to enhance training in DMCA for medical students, residents, and practising physicians have been initiated in Alberta. These educational opportunities have begun to address identified learning needs and enhance knowledge and awareness, which might catalyze physician engagement in capacity-assessment efforts. Training can improve DMCA and we should strive to ensure that physicians are trained as well in DMCA as they are in managing other geriatric syndromes.32–34

Based on our review of the literature, it is clear that there is no consistent approach to conducting DMCAs.29–31,35–41 Keenly aware of the necessity of comprehensiveness regarding DMCAs, and determination of least intrusive and restrictive outcomes, participants appreciated having strategies and supports that assisted them in conducting DMCAs. Strategies and supports including a patient-centred care approach, best practice process, and tools to guide the use of the DMCA model, particularly the worksheets, were highly valued by the focus group physicians.24 The participants reported that having appropriate tools demystifies the process, enhances confidence, and might reduce the frequency of DMCAs done on an ad hoc basis.38 Enhanced capacity of HCPs and interprofessional teams in this practice area can enable FPs to focus on mentoring, attending to complex cases that require medical expertise, and advocating for patients. To address issues of isolation, FPs working in remote or rural areas, or without access to interprofessional team support, could benefit from peer support, mentoring, and collaboration. Establishment of virtual communities of practice might address issues of isolation and calls for consultative and mentoring support, as might an on-call physician mentoring team through which physicians can access consultative support from colleagues.

The finding that education offers an opportunity to be informed about issues that might otherwise disincentivize FPs from engaging in DMCAs (eg, lack of support, challenges with family members, and remuneration and medicolegal concerns) is of particular value. The practice barriers including family conflict, fear of liability, and remuneration did not appear in the scoping review, and these findings add to the current literature. Adaptation of the model’s education and training resources to suit FP needs might aim to address these concerns. Enhanced knowledge and skill around both conflict resolution and legislation might enable FPs to feel more confident when conducting DMCAs and to diffuse conflicts. Greater knowledge of legislation and reassurance of protection under the acts might also mitigate medicolegal concerns. Remuneration is a further area that participants identified that could be addressed with advocacy through provincial medical associations.

Family physicians are well situated in the health care system to engage in DMCAs; they are committed to person-centred care and have long-term relationships with their patients. These long-term relationships are important when determining DMC, as the physician can note changes in cognitive abilities over time that might affect DMC and make recommendations based on their clinical expertise. In addition, FPs can facilitate and empower interprofessional team members to work to full scope, allowing their skills and expertise to be used for complex cases, mentoring, and advocacy for patients. Education is needed to develop expertise and increase skills to make the system more effective.

Limitations

There is a paucity of literature on physician training and engagement in DMCAs. First, there was only 1 focus group comprising 7 FPs involved in this pilot study, followed by interviews with 2 FPs; however, the findings uncovered during qualitative analyses echoed the themes developed from the published literature and expanded on them, particularly with regard to barriers to DMCA engagement. In addition, saturation was reached and new themes did not emerge during the follow-up interviews. Second, focus group participants were self-selected, thus participants were likely only those interested in DMCAs and, as such, might have differed from those who are not as interested in completing DMCAs. Third, participants were predominantly from the Edmonton area and might have represented physicians who have more experience with DMCAs than average FPs do owing to their training in care of the elderly or experience in elderly care. Nevertheless, the research sample included experienced FPs, medical residents, and new practitioners, thus offering various perspectives based on work in different clinical contexts. Finally, an expansive evaluation of DMCAs conducted by FPs using the model, review of patient charts, and collection of data from patients and families were beyond the scope of the project.

Future research

This study is part of a larger program of research examining the DMCA model, its effectiveness, and contextualization. Further data collection will assist in determining whether educational efforts and supports, such as those indicated here, might facilitate enhanced physician engagement and competencies. Research into the model’s application by FPs and HCPs working independently and on interprofessional teams in rural and community contexts, and across various settings and client populations, is warranted. This work will inform cross-ministerial working groups with the potential to influence policy.

Conclusion

With proper training, FPs are well positioned to effectively conduct DMCAs. This research project addresses informed ways to better train, support, and engage FPs conducting DMCAs. It will guide enhancement of educational components of the DMCA model and incorporation of additional content into the current workshops. Facilitators of FP engagement in DMCAs are their commitment to patient-centred care and concern with providing high-quality service to patients under their care. However, for FPs to be willing to engage in the process, barriers they experience, such as issues of isolation, family engagement, liability, and remuneration need to be addressed. We would suggest that access to an interprofessional team and education and tools available through the DMCA model, as well as the availability of mentoring or consultative services, could increase FPs confidence and engagement in DMCAs. Advocacy for adequate billing codes via the medical associations is also warranted and under way.

Acknowledgments

This study received funding from the Department of Family Medicine at the University of Alberta. We thank Darlene Blischak for assisting with the scoping literature review.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS

As the population ages and the number of people with dementia rises, there will be an increased demand for decision-making capacity assessments (DMCAs). This study found that physician training for DMCA is suboptimal and that more education and training is required.

Participants in this study appreciated having strategies and supports that assisted them in conducting DMCAs; these included a patient-centred care approach, best practice processes, and tools to guide the use of the DMCA model, particularly the worksheets.

Participants offered a number of recommendations that might lead to facilitating better engagement in DMCAs: enhanced training and education, access to interprofessional teams, consultative or mentoring support, and remuneration.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR

Avec le vieillissement de la population et l’augmentation des cas de démence, le nombre des demandes d’évaluation de la capacité de prendre des décisions (ECPD) risque d’augmenter. Cette étude montre que la préparation des médecins en ce domaine est sous-optimale, et qu’il faudra davantage de formation théorique et pratique.

Les participants à cette étude ont apprécié les stratégies et les outils les aidant à mieux faire ces ECPD; il s’agissait entre autres d’une méthode axée sur le patient, de processus de meilleures pratiques et d’outils facilitant l’utilisation du modèle d’ECPD, notamment les feuillets d’exercice.

Les participants ont émis plusieurs recommandations susceptibles d’améliorer la façon d’effectuer ces ECPD : améliorer la formation théorique et pratique, faciliter l’accès à des équipes interprofessionnelles et à de l’aide sous forme de consultations ou de mentorat, et améliorer la rémunération.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Cet article a fait l’objet d’une révision par des pairs.

Contributors

Drs Charles, Parmar, Brémault-Phillips, and Dobbs and Mr Sluggett contributed substantially to the conception and design of the study; acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data; drafted the article and revised it critically for important intellectual content; and gave final approval of the version to be published. Dr Sacrey contributed substantially to the analysis and interpretation of data; drafted the article and revised it critically for important intellectual content; and gave final approval of the version to be published.

Competing interests

None declared

References

- 1.Marson DC, Martin RC, Wadley V, Griffith HR, Snyder S, Goode PS, et al. Clinical interview assessment of financial capacity in older adults with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(5):806–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02202.x. Epub 2009 Apr 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berg JW, Appelbaum PS, Lidz CW, Parker LS. Informed consent: legal theory and clinical practice. 2nd ed. Fair Lawn, NJ: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coverdale J, McCullough LB, Molinari V, Workman R. Ethically justified clinical strategies for promoting geriatric assent. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;21(2):151–7. doi: 10.1002/gps.1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brindle N, Holmes J. Capacity and coercion: dilemmas in the discharge of older people with dementia from general hospital settings. Age Ageing. 2005;34(1):16–20. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afh228. Epub 2004 Oct 20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Etchells E. Aid to capacity evaluation. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto, Joint Centre for Bioethics; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mukherjee D, McDonough C. Clinician perspectives on decision-making capacity after acquired brain injury. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2006;13(3):75–83. doi: 10.1310/2M1U-71FQ-QV33-56PX. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sturman ED. The capacity to consent to treatment and research: a review of standardized assessment tools. Clin Psychol Rev. 2005;25(7):954–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization . First WHO ministerial conference on global action against dementia. Geneva, Switz: World Health Organization; 2015. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/179537/1/9789241509114_eng.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 2016 Dec 2. [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization . The epidemiology and impact of dementia. Current state and future trends. Geneva, Switz: World Health Organization; 2015. Available from: www.who.int/mental_health/neurology/dementia/dementia_thematicbrief_epidemiology.pdf. Accessed 2016 Dec 2. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alzheimer Society of Canada [website]. Dementia numbers in Canada. Toronto, ON: Alzheimer Society of Canada; 2016. Available from: www.alzheimer.ca/en/About-dementia/What-is-dementia/Dementia-numbers. Accessed 2016 Dec 2. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Statistics Canada [website]. Population projections for Canada (2013 to 2063), provinces and territories (2013 to 2038): technical report on methodology and assumptions. Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada; 2015. Available from: www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/91-620-x/91-620-x2014001-eng.htm. Accessed 2016 Dec 2. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Statistics Canada [website]. Population projections: Canada, the provinces, and territories, 2013 to 2038. Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada; 2014. Available from: www.statcan.gc.ca/daily-quotidien/140917/dq140917a-eng.htm. Accessed 2016 Dec 2. [Google Scholar]

- 13.MacCourt P, Wilson K, Tourigny-Rivard MF. Guidelines for comprehensive mental health services for older adults in Canada. Executive summary. Calgary, AB: Mental Health Commission of Canada; 2011. Available from: www.mentalhealthcommission.ca/sites/default/files/Seniors_MHCC_Seniors_Guidelines_ExecutiveSummary_ENG_0_1.pdf. Accessed 2016 Dec 2. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moye J, Marson DC. Assessment of decision-making capacity in older adults: an emerging area of practice and research. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2007;62(1):P3–11. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.1.p3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Statistics Canada [website]. Population by age and sex. Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada; 2015. Available from: www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/91-215-x/2012000/part-partie2-eng.htm. Accessed 2016 Dec 6. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Canadian Institute for Health Information. Health care in Canada, 2011. A focus on seniors and aging. North York, ON: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2011. Available from: https://secure.cihi.ca/free_products/HCIC_2011_seniors_report_en.pdf. Accessed 2016 Dec 2. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim SY, Karlawish JH, Caine ED. Current state of research on decision-making competence of cognitively impaired elderly persons. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;10(2):151–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization. Dementia. A public health priority. Geneva, Switz: World Health Organization; 2015. Available from: www.who.int/mental_health/neurology/dementia/dementia_thematicbrief_executivesummary.pdf. Accessed 2016 Dec 2. [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization. Ensuring a human rights-based approach for people living with dementia. Geneva, Switz: World Health Organization; 2015. Available from: www.who.int/mental_health/neurology/dementia/dementia_thematicbrief_human_rights.pdf. Accessed 2016 Dec 5. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Province of Alberta. Personal Directive Act. Revised statutes of Alberta 2000. Edmonton, AB: Alberta Queen’s Printer; 2013. Available from: www.qp.alberta.ca/documents/Acts/p06.pdf. Accessed 2016 Dec 5. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Province of Alberta. Powers of Attorney Act. Revised statutes of Alberta 2000. Edmonton, AB: Alberta Queen’s Printer; 2014. Available from: www.qp.alberta.ca/documents/Acts/p20.pdf. Accessed 2016 Dec 5. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Province of Alberta. Adult Guardianship and Trusteeship Act. Statutes of Alberta, 2008. Edmonton, AB: Alberta Queen’s Printer; 2013. Available from: www.qp.alberta.ca/documents/Acts/A04P2.pdf. Accessed 2016 Dec 5. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brémault-Phillips SC, Parmar J, Friesen S, Rogers LG, Pike A, Sluggett B. An evaluation of the decision-making capacity assessment model. Can Geriatr J. 2016;19(3):83–96. doi: 10.5770/cgj.19.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parmar J, Brémault-Phillips S, Charles L. The development and implementation of a decision-making capacity assessment model. Can Geriatr J. 2015;18(1):15–28. doi: 10.5770/cgj.18.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patton MQ. Developmental evaluation. Applying complexity concepts to enhance innovation and use. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological frame-work. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5:69. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roper J, Shapira J. Ethnography in nursing research. Volume 1. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seyfried L, Ryan KA, Kim SY. Assessment of decision-making capacity: views and experiences of consultation psychiatrists. Psychosomatics. 2013;54(2):115–23. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2012.08.001. Epub 2012 Nov 27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Racine CW, Billick SB. Assessment instruments of decision-making capacity. J Psychiatry Law. 2012;40(2):243–63. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shreve-Neiger A, Houston CM, Christensen KA, Kier FJ. Assessing the need for decision-making capacity education in hospitals and long term care (LTC) settings. Educ Gerontol. 2008;34(5):359–71. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karlawish JHT, Schmitt F. Why physicians need to become more proficient in assessing their patients’ competency and how they can achieve this. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(8):1014–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb06904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Earnst K, Marson DC, Harrell LE. Cognitive models of physicians’ legal standard and personal judgments of competency in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(8):919–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb06888.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marson DC, Earnst KS, Jamil F, Bartolucci A, Harrell LE. Consistency of physicians’ legal standard and personal judgments of competency in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(8):911–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb06887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sessums LL, Zembrzuska H, Jackson JL. Does this patient have medical decision-making capacity? JAMA. 2011;306(4):420–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ministry of the Attorney General, Capacity Assessment Office. Guidelines for conducting assessments of capacity. Ottawa, ON: Ministry of the Attorney General, Capacity Assessment Office; 2005. Available from: www.attorneygeneral.jus.gov.on.ca/english/family/pgt/capacity/2005-06/guide-0505.pdf. Accessed 2016 Dec 6. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yukon Department of Justice. Guidelines for conducting incapability assessments for the purpose of guardianship applications. Yukon, NT: Yukon Department of Justice; 2005. Available from: www.publicguardianandtrustee.gov.yk.ca/pdf/guidelines_for_conducting_assessments.pdf. Accessed 2016 Dec 6. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pope TM, Sellers T. Legal briefing: the unbefriended: making healthcare decisions for patients without surrogates (part 1) J Clin Ethics. 2012;23(1):84–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hermann H, Trachsel M, Mitchell C, Biller-Andorno N. Medical decision-making capacity: knowledge, attitudes, and assessment practices of physicians in Switzerland. Swiss Med Wkly. 2014;144:w14039. doi: 10.4414/smw.2014.14039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sorinmade O, Strathdee G, Wilson C, Kessel B, Odesanya O. Audit of fidelity of clinicians to the mental capacity act in the process of capacity assessment and arriving at best interests decisions. Qual Ageing Older Adults. 2011;12(3):174–9. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kapp MB. Assessing assessments of decision-making capacity: a few legal queries and commentary on “assessment of decision-making capacity in older adults”. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2007;62(1):P12–3. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.1.p12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Griffith R, Tengnah C. Assessing decision-making capacity: lessons from the court of protection. Br J Community Nurs. 2013;18(5):248–51. doi: 10.12968/bjcn.2013.18.5.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tunzi M, Spike JP. Assessing capacity in psychiatric patients with acute medical illness who refuse care. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2014;16(6) doi: 10.4088/PCC.14br01666. Epub 2014 Nov 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Curtis JR. Life and death decisions in the middle of the night: teaching the assessment of decision-making capacity. Chest. 2010;137(2):248–50. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sexton M. Assessing capacity to make decisions about long-term care needs: ethical perspectives and practical challenges in hospital social work. Ethics Soc Welf. 2012;6(4):411–7. [Google Scholar]