Abstract

Childhood epilepsy is common in Africa. However, there are little data on the developmental and behavioral problems experienced by children living with epilepsy, especially qualitative data that capture community perceptions of the challenges faced by these children. Identifying these perceptions using qualitative approaches is important not only to help design appropriate interventions but also to help adapt behavioral tools that are culturally appropriate. We documented the description of these problems as perceived by parents and teachers of children with or without epilepsy. The study involved 70 participants. Data were collected using in-depth interviews and focus group discussions and were analyzed using NVIVO to identify major themes. Our analysis identified four major areas that are perceived to be adversely affected among children with epilepsy. These included internalizing and externalizing problems such as aggression, temper tantrums, and excessive crying. Additionally, developmental delay, especially cognitive deficits and academic underachievement, was also identified as a major problematic area. There is a need to supplement these findings with quantitative estimates and to develop psychosocial and educational interventions to rehabilitate children with epilepsy who have these difficulties.

Keywords: Epilepsy, Africa, Qualitative, Developmental problems, Behavioral problems

1. Introduction

Epilepsy is a common neurological disorder in resource poor settings, where it is often caused by brain insults, including infectious disease and perinatal complications [1,2]. It is estimated that nearly 70 million people live with epilepsy worldwide; of these people, 10 million live in the African continent [3]. Epilepsy in children is associated with cognitive impairments [4–6], academic underachievement [7,8], and behavioral and emotional problems [9]. However, most of the evidence arises from studies carried out in Western countries, and there is paucity of data from Africa. Differences in formal health systems, underlying risk factors and social support available for people with epilepsy (PWE) in Africa compared with those in the West, imply that evidence from the West cannot be extrapolated to formulate or implement intervention programs for PWE in Africa [10,11]. There is, therefore, a need for more African-based mental health studies among PWE so as to provide an evidence base that can be used to develop appropriate interventions.

The impetus for this study is provided by three interlinked factors. First, there are few studies from Africa such as those by Kariuki et al. [9], Lagunju et al. [12], and Burton et al. [13], all of which used quantitative standardized methodologies to demonstrate an increased prevalence of behavioral problems in children with epilepsy compared with controls. While the earlier approaches allow for the quantification of the problem, they did not provide information on the community’s perceptions of the behavioral and developmental challenges faced by children with epilepsy. In studying aspects related to behavioral outcomes among children, inclusion of community voices is especially important since there are observations showing contextual and cultural differences in the way people present and express mental health symptoms. Qualitative data are important in capturing cross cultural nuances in understanding ill-health and its consequences whenever it exists.

Second, Africa lacks culturally appropriate and standardized measures for use in evaluating childhood developmental and behavioral problems. The literature provides many examples to show that the simple translation of measures for childhood outcomes from the West into local languages may not be an adequate approach and that, very often, researchers have to make significant adaptations to these measures to ensure their adequacy [14–16]. Qualitative research is useful in ensuring that study materials, questions, idioms, and stimuli are both contextually relevant and culturally appropriate [17]. Qualitative studies provide additional information that is useful in designing studies and in adapting methods and questionnaires for use in large-scale epidemiological surveys [18]. Therefore, as a first step in carrying out a large community survey aimed at quantifying the burden of behavioral problems in children with acute seizures, we carried out this study to understand, in part, the idioms and phrases that can be used to define behavioral problems in this area while adapting and validating the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) and the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) [19].

Third, the inclusion of community voices in understanding the challenges of chronically ill children is important in providing ecological validation of quantitative data and in developing appropriate interventions. In the context of psychological assessment, ecological validity refers to the extent to which ‘deficits’ observed during controlled assessments can be replicated or observed in the day-to-day function of a person across different settings [20].

The current study was set out to answer the following question: What are the developmental and behavioral problems experienced by children with epilepsy in Kilifi as perceived by parents and teachers of children with epilepsy and of those without epilepsy?

2. Methods

2.1. Study site

The study was undertaken in Kilifi County, Kenya. Kilifi County is one of the poorest counties in Kenya, with more than 67% of the people living below the poverty line (living on less than a dollar a day), indicating limited access to essential food and nonfood items [21]. Most of the people in Kilifi depend on subsistence farming, but frequent failure of rainfall has resulted in insufficient farming products, compromising food access in the general population. Epilepsy is common in children living in Kilifi, with an adjusted prevalence of lifetime and active epilepsy as 41/1000 (95% confidence interval (CI): 31–51) and 11/1000 (95% CI: 5–15) and an incidence of active epilepsy of 187 per 100,000 per year (95% CI: 133–256) in children 6–12 years of age [22]. We have found that behavioral problems are very common in children with epilepsy [9]. At the Kilifi County Hospital, there is a clinic dedicated to the care of people living with epilepsy. The clinic provides assessment including electroencephalography, antiepileptic medication (phenobarbital, phenytoin, carbamazepine, and/or sodium valproate), outpatient services, and counseling for people living with epilepsy and their caregivers.

2.2. Study participants and sampling

For mothers of children with epilepsy and of those without epilepsy, the sampling was based on databases at the KEMRI-CGMRC. Two sets of databases were used. For parents of children with epilepsy (n = 40), we used the data for children in a cohort with epilepsy [22]. We made a list of all parents who have children with epilepsy ≤ 12 years of age. We identified 40 parents of children without epilepsy ≤ 12 years of age from the Kilifi Demographic Surveillance Data [23]. These families were visited at home and recruited to join either the focus groups or the in-depth interviews based on availability for either. Recruitment was carried out until we had reached a point of saturation where no more new data were being collected during the interviews. For the sample of teachers, we conveniently selected two schools from Kilifi and randomly selected teachers from these schools who teach children in the lower primary classes (since most of them will be less than 12 years of age) to participate in either the focused group discussions or the individual in-depth interviews. Only teachers who were available at the time of the appointments participated (See table 1 for details on the participants).

Table 1.

Participants’ characteristics.

| Group | Participants’ median age in years (IQR)a | In-depth interviews | Focus group discussion | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parents/caregivers of children with epilepsy | 35.0 (28.5–39.3) | 10 | 3 FGDs N = 7 N = 6 N = 4 |

27 |

| Parents of children without epilepsy | 23.0 (20.5–26.0) | 11 | 2 FGDs N = 6 N = 7 |

24 |

| Teachers | 32.0 (27.0–41.0) | 5 | 2 FGDs N = 7 N = 7 |

19 |

| Total | 30.5 (23.7–37.2) | 26 | 44 | 70 |

IQR = interquartile range.

a Age range reported for the participants who provided us with this information. Some (33%) participants did not provide us with this information.

2.3. Data collection

Data were collected using in-depth interviews and focus group discussions. All interviews and focus group discussions were audio-taped. Each interview and focus group discussion took approximately 1 h. The interviews were guided by a standard set of questions to ensure standardization. Probes and clarifications were sought as deemed necessary. Participants were asked to express themselves in the language in which they were most comfortable; thus, sessions were conducted in both Kiswahili and Kigiriama interchangeably.

2.4. Interview tool

A checklist of questions was developed by the research team through discussions and consensus. Through initial interviews and discussions of the initial transcripts among the study team, the questions were modified. The items were clarified through an iterative process, involving the first few FGDs and in-depth interviews; this was carried out to ensure clarity in the questions presented and in the responses received.

2.5. Data management and analysis

The final transcripts used for analysis were generated from the audio-taped materials. Data were analyzed using the NVIVO 10 software program through content analysis [24,25]. This process was completed based on prior defined themes of interest. Based on five randomly selected transcripts, the first author (AA) and the fourth author (JG) independently generated coding schemes and identified themes. Three of the authors (AA, JG, and JTD) then met to discuss the coding and generated themes. Based on this process, an agreed-upon coding scheme was generated and AA coded all the remaining transcripts. After coding the transcripts, AA and JG discussed the coding item-by-item with a view to ensuring consistency in coding. Direct quotes from the transcripts are presented to support the identified themes. Three of the authors – AA, JG, and JTD – checked for the accuracy of the translations and interpretation of the quotes presented.

2.6. Ethical considerations

The Kenya Medical Research Institute National Scientific and Ethical Committees approved the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants prior to participation.

3. Results

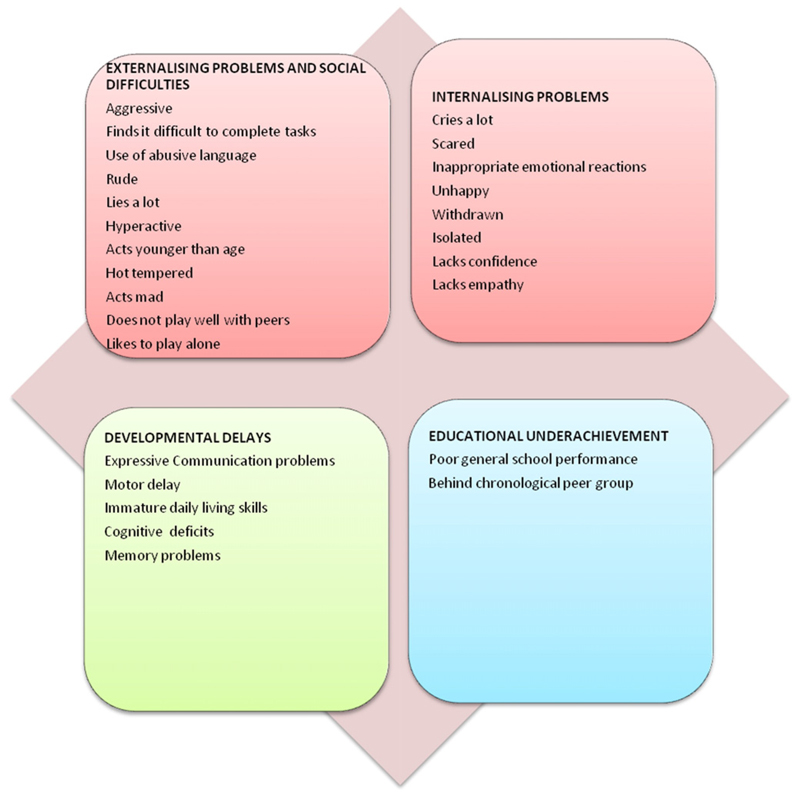

A total of 70 participants were involved in this study, of whom 26 were parents of children with epilepsy, 1 was a sibling caregiver of a child with epilepsy, 24 were parents of children without epilepsy, and 19 were teachers. All participants were female, with the exception of two (one teacher and one sibling caregiver of a child with epilepsy). Based on previously identified themes and codes, we identified 4 major areas of concerns from the participants involved in this study: externalizing problems and social difficulties, internalizing problems, developmental delays, and academic underachievement (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Summary of developmental and behavioral problems as identified by our participants.

3.1. Externalizing problems and social difficulties

All participants interviewed indicated that children with epilepsy presented with features of externalizing problems. The most frequently mentioned externalizing problem was aggressive behavior.

“He is aggressive.”

[FGD, teachers]

“There was a student who experienced this problem (i.e. had epilepsy), at first the child was not aggressive but with time they changed and become aggressive as a way to deal with the mockery from other students.”

[FGD, teachers]

“Beating others even when they have done nothing to incite the fight….”

[In-depth interview, Parent of a child without epilepsy without epilepsy]

Other externalizing problems mentioned included telling lies and being hyperactive among others (see Fig. 1 for the detailed summary of these problems). Some of the social difficulties mentioned included problems with interacting/playing well with others.

“They like disturbing/bothering their peers….”

[FGD, teachers]

“He disturbs others. He plays forcefully and interferes with the other kids playing….”

[In-depth interview, Parent of a child without epilepsy]

3.2. Internalizing problems

Additionally, parents and teachers noted that many children with epilepsy experienced a variety of internalizing emotional problems such as being unhappy, crying a lot, inappropriate emotional expressions, and extreme mood changes.

“He is frequently scared or anxious or afraid.”

[Individual interview, teacher]

“Unhappy.”

[FGD, parents of children without epilepsy]

“My child shows behavioural traits I find hard to understand sometimes. Sometimes you will see he is extremely happy; when I see that I know he will fit, while other times he is extremely sad.”

[FGD, parent of a child with epilepsy]

“They isolate themselves, they like staying alone….”

[FGD, teachers]

3.3. Developmental delays

Developmental delays were mentioned as some of the issues faced by children living with epilepsy. Intellectual disabilities, lack of communication skills, and delayed motor skills were some of the developmental delays participants in this study highlighted.

“They change and become mentally slow as if they are not fully aware of themselves.”

[FGD, teachers]

“Compared to his sibling who is younger, I feel mentally he is different, because he suffered from this illness (epilepsy) I think he has not matured mentally, although he no longer fits any more….”

[Individual interview, mother of a child with epilepsy]

“He is seven years old and he cannot sit.”

[FGD, parents of children without epilepsy]

“Even now he does not sit or talk.”

[In-depth interview, parent of a child with epilepsy]

Significant problems were reported in terms of daily living skills, with parents of children living with epilepsy noting that their children were delayed in important skills in normal development such as dressing and feeding themselves and bowel control.

“She cannot feed herself….”

[Individual interview, parent of a child with epilepsy]

“Cannot control bowel movement… she soils herself whenever she is, then you have to clean her up.”

[Individual interview, parent of a child with epilepsy]

3.4. Poor educational outcomes

Other than intellectual disabilities, our key informants mentioned that children with epilepsy fell behind in their educational outcomes. It was noted that the children with epilepsy were several grades behind their peers.

“It is because of schooling; because he does not comprehend anything… he is old but younger children perform better than him at school.”

[In-depth interview, parent of a child with epilepsy]

“In terms of education it does not go so well, he should have been in class 2 but next year is when he will be joining class one, this disease is causing him to be behind in his learning….”

[FGD, parent of a child with epilepsy]

3.5. Additional observations

Though not a focus of the study, it was clear from our observations that parents of children without epilepsy who had not experienced living with someone with epilepsy had limited knowledge of the challenges and difficulties experienced by children living with epilepsy.

4. Discussion

We set out to elicit community perceptions of developmental and behavioral problems faced by children living with epilepsy in Kilifi, Kenya. Our findings indicated that there are four key areas of concerns to the community members. These include developmental delays, e.g., delayed motor milestones, poor scholastic outcomes, and externalizing and internalizing problems. These results are important from two perspectives. First, the results are consistent with those reported elsewhere using both qualitative and quantitative approaches [6,26]. For instance, Mushi et al. [26] using qualitative approaches noted that caregivers of children with epilepsy reported that children with epilepsy experience behavioral problems, learning difficulties, and difficulties with peer relationships. Similarly, Chambers et al. [6], in a case control study in Jamaica where a wide range of neuropsychological measures were administered, observed that epilepsy had a direct impact on scores of memory, language, attention, and mathematical abilities. The Chambers et al. results mirror some of the qualitative findings in the Kenyan children, although we did not use a comparison group and theirs was a quantitative study. The convergence between our results and qualitative and quantitative data arising from different settings serves to emphasize the detrimental developmental and behavioral consequences of childhood epilepsy.

Second, participating parents and teachers were able to discuss and identify the challenges faced by children with epilepsy. These results have significant practical implications, as earlier studies indicate that, when members of the community perceive something to be a challenge, they are likely to be more willing to participate in intervention programs aimed at addressing that challenge. Thus, the parents’ understanding of these developmental and behavioral problems should facilitate their enrolment and engagement in behavioral and educational intervention programs undertaken in this area. For policy makers and practitioners, this observation should provide more impetus for developing appropriate programs to address the developmental and behavioral needs of children with epilepsy.

As mentioned in the Introduction section, one of the key reasons for carrying out this qualitative study was to inform the design of a larger study on the impact of seizures on child outcome. The data collected were used to validate content for some of the key measures to be administered. After thematically analyzing our data, we examined the measures available and critically evaluated the extent to which they capture ‘core deficits’ identified by our community members. Our results indicate that community members when probed about the challenges faced by children with epilepsy will detect most of the behavioral syndromes assessed by some of the key scales we have translated and or adapted and validated for use in this area, namely, the CBCL [27] and the SDQ [19]. Participants in our study perceived that both externalizing (fighting, hyperactivity, and lying) and internalizing (unhappy and withdrawn) problems were experienced by children living with epilepsy. These results provide information on content validity of the CBCL and the SDQ in children with seizure disorders, thereby allowing us to proceed with adaptation and validation of the CBCL for use in examining behavioral problems among these children. Moreover, it is clear that a comprehensive evaluation of behavioral, academic and developmental functioning is essential if we are to fully understand the behavioral and developmental impact of childhood epilepsy. An approach where qualitative work is carried out prior to adaptation of scales, while it may be time-consuming, is recommended [17] and is widely used in the process of tool adaptation as it allows for the development of culturally sensitive measures. Additionally, we find a high level of convergence between the reports of parents and teachers. This implies that the developmental and behavioral difficulties experienced by children with epilepsy have an impact on their functioning both at school and at home and that parent- and teacher-based measures of impact of epilepsy on children’s development and behavior are likely to elicit similar patterns of results. This supports future quantitative studies in which degree of agreement between multiple informants (e.g., teacher and parent) is used to assess the impact of epilepsy on childhood functioning and behavior.

Though not an aim of this research, it is noteworthy how little parents without children with epilepsy knew of the challenges faced by those living with this condition. Those who had not had ‘first-hand’ experience with children with epilepsy were largely unaware of the challenges faced by these children and their families. Their unawareness of the problems may increase the stigma associated with epilepsy; thus, there is a need to educate the community about the behavioral and neurodevelopmental disabilities and challenges faced by children with epilepsy. Given the high incidence of epilepsy in this rural setting [23], there is a need to raise awareness about the needs of children living with epilepsy as a step towards ensuring that their developmental and behavioral needs are addressed.

5. Limitations

Views from religious leaders and traditional healers were not sought and should be considered in future studies since these two stakeholders interact with people with epilepsy. Another limitation of our study is that we surveyed the general opinion on the perceived impact of epilepsy on child behavior and development; however, there is considerable variation in the level of functioning of children with epilepsy based on disease characteristics (e.g., severity and presence of other comorbidities) and sociodemographic factors (e.g., age and sex). Qualitative studies are by nature small and focused; therefore, it was not possible to look at the perceptions of parents and teachers from different subgroups (e.g., active vs. inactive epilepsy). However, future qualitative work may be able to focus on particular groups, thereby clarifying the impact of different epilepsy syndromes on childhood functions.

6. Conclusions

In conclusion, our pattern of results is similar to that observed elsewhere, and behavioral problems mentioned closely mirrored the items in the standardized behavioral questionnaires such as the CBCL and the SDQ, although these tools mainly focus on the assessment of behavioral problems which would only partially capture the concerns of the community participants. The results provide initial data on the content and face validity of the CBCL and the SDQ. These results informed our decision to proceed with adaptation and validation of the CBCL and the SDQ for use in screening the prevalence of emotional and behavioral problems and also the inclusion of measures of developmental and academic progress in a large community-based study on the Kenyan coast. Moreover, the data indicated that behavioral interventions for children with epilepsy would likely be welcomed by parents and teachers in this rural area since they have a good understanding of the problems faced by their children with epilepsy.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust (Research Training Fellowship to SK (099782) and Senior Clinical Fellowship to CN (083744)). Amina Abubakar was supported by the University of Oxford Tropical Network Fund and Wellcome Trust grant 092654/Z/10/A. We would like to thank the study participants for taking time to be part of this study. This paper is published with the permission of the director of KEMRI.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Mbuba CK, Newton CR. Packages of care for epilepsy in low- and middle-income countries. PLoS Med. 2009;6(10):e1000162. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kamuyu G, Bottomley C, Mageto J, Lowe B, Wilkins PP, Noh JC. Exposure to multiple parasites is associated with the prevalence of active convulsive epilepsy in sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8(5):e2908. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ngugi AK, Bottomley C, Kleinschmidt I, Sander JW, Newton CR. Estimation of the burden of active and life-time epilepsy: a meta-analytic approach. Epilepsia. 2010;51(5):883–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02481.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reilly C, Atkinson P, Das KB, Chin RF, Aylett SE, Burch V, et al. Neurobehavioral comorbidities in children with active epilepsy: a population-based study. Pediatrics. 2014;133(6):e1586–93. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rathouz PJ, Zhao Q, Jones JE, Jackson DC, Hsu DA, Stafstrom CE, et al. Cognitive development in children with new onset epilepsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2014;56(7):635–41. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.12432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chambers RM, Morrison-Levy N, Chang S, Tapper J, Walker S, Tulloch-Reid M. Cognition, academic achievement, and epilepsy in school-age children: a case–control study in a developing country. Epilepsy Behav. 2014;33:39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aldenkamp AP, Weber B, Overweg-Plandsoen WC, Reijs R, van Mil S. Educational underachievement in children with epilepsy: a model to predict the effects of epilepsy on educational achievement. J Child Neurol. 2005;20(3):175–80. doi: 10.1177/08830738050200030101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reilly C, Neville BG. Academic achievement in children with epilepsy: a review. Epilepsy Res. 2011;97(1):112–23. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2011.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kariuki SM, Abubakar A, Holding PA, Mung’ala-Odera V, Chengo E, Kihara M, et al. Behavioral problems in children with epilepsy in rural Kenya. Epilepsy Behav. 2012;23(1):41–6. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2011.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kariuki SM, Matuja W, Akpalu A, Kakooza-Mwesige A, Chabi M, Wagner RG, et al. Clinical features, proximate causes, and consequences of active convulsive epilepsy in Africa. Epilepsia. 2014;55(1):76–85. doi: 10.1111/epi.12392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Newton CR, Garcia HH. Epilepsy in poor regions of the world. Lancet. 2012;380(9848):1193–201. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61381-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lagunju IA, Bella-Awusah TT, Takon I, Omigbodun OO. Mental health problems in Nigerian children with epilepsy: associations and risk factors. Epilepsy Behav. 2012;25(2):214–8. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2012.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burton K, Rogathe JH, unter E, Burton M, Swai M, Todd J, et al. Behavioural comorbidity in Tanzanian children with epilepsy: a community-based case–control study. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2011;53(12):1135–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2011.04109.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Malda M, van de Vijver FJ, Srinivasan K, Transler C, Sukumar P. Traveling with cognitive tests: testing the validity of a KABC-II adaptation in India. Assessment. 2010;17(1):107–15. doi: 10.1177/1073191109341445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holding PA, Taylor HG, Kazungu SD, Mkala T, Gona J, Mwamuye B, et al. Assessing cognitive outcomes in a rural African population: development of a neuropsychological battery in Kilifi District, Kenya. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2004;10(02):246–60. doi: 10.1017/S1355617704102166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holding P, Kitsao-Wekulo P. Is assessing participation in daily activities a suitable approach for measuring the impact of disease on child development in African children? J Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2009;21(2):127–38. doi: 10.2989/JCAMH.2009.21.2.4.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holding P, Abubakar A, Kitsao-Wekulo P. A systematic approach to test and questionnaire adaptations in an African context. 2008 (3mc) [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Jong JT, Van Ommeren M. Toward a culture-informed epidemiology: combining qualitative and quantitative research in transcultural contexts. Transcult Psychiatry. 2002;39(4):422–33. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goodman R. The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: a research note. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1997;38(5):581–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barkley RA. The ecological validity of laboratory and analogue assessment methods of ADHD symptoms. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1991;19(2):149–78. doi: 10.1007/BF00909976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Government of Kenya. Poverty eradication strategy paper, Kilifi district 2001–2004. Nairobi: Ministry of Finance and Planning; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ngugi AK, Bottomley C, Scott JA, Mung’ala-Odera V, Bauni E, Sander JW, et al. Incidence of convulsive epilepsy in a rural area in Kenya. Epilepsia. 2013;54(8):1352–9. doi: 10.1111/epi.12236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scott JA, Bauni E, Moisi JC, Ojal J, Gatakaa H, Nyundo C, et al. Profile: the Kilifi Health and Demographic Surveillance System (KHDSS) Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41(3):650–7. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Silverman D. Doing qualitative research: a practical guide. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mushi D, Burton K, Mtuya C, Gona JK, Walker R, Newton CR. Perceptions, social life, treatment and education gap of Tanzanian children with epilepsy: a community-based study. Epilepsy Behav. 2012;23(3):224–9. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2011.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Achenbach TM, Edelbrock CS. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist and Revised Child Behavior Profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gladstone M, Lancaster GA, Umar E, Nyirenda M, Kayira E, van den Broek NR, et al. The Malawi Developmental Assessment Tool (MDAT): the creation, validation, and reliability of a tool to assess child development in rural African settings. PLoS Med. 2010;7(5):e1000273. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]