Abstract

Background

Previously, using an adenoviral vector, we showed that miniature pigs could provide a valuable and affordable large animal model for pre-clinical gene therapy studies to correct parotid gland radiation damage. However, adenoviral vectors lead to short-term transgene expression and, ideally, a more stable correction is required. In the present study, we examined the suitability of using a serotype 2 adeno-associated viral (AAV2) vector to mediate more stable gene transfer in the parotid glands of these animals.

Methods

Heparan sulfate proteoglycan was detected by immunohistochemistry. β-galactosidase expression was determined histochemically. An AAV2 vector encoding human erythropoietin (hEpo) was administered via Stensen’s duct. Salivary and serum hEpo levels were measured using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Serum chemistry and hematological analyses were performed and serum antibodies to hEpo were measured throughout the study. Vector distribution was determined by a quantitative polymerase chain reaction.

Results

Transgene expression was vector dose-dependent, with high levels of hEpo being detected for up to 32 weeks (i.e. the longest time studied). hEpo reached maximal levels during weeks 4–8, but declined to approximately 25% of these values by week 32. Haematocrits were elevated from week 2. Transduced animals exhibited low serum anti-hEpo antibodies (1 : 8–1 : 16). Vector biodistribution at animal sacrifice revealed that most copies were in the targeted parotid gland, with few being detected elsewhere. No consistent adverse changes in serum chemistry or hematology parameters were seen.

Conclusions

AAV2 vectors mediate extended gene transfer to miniature pig parotid glands and should be useful for testing pre-clinical gene therapy strategies aiming to correct salivary gland radiation damage.

Keywords: adeno-associated virus, gene therapy, miniature pig, parotid gland, salivary hypofunction

Introduction

The importance of using large animal models in the development of clinical applications of gene transfer has been widely appreciated [1–4]. Although no animal model is entirely representative of human physiology, large animals can provide a more appropriate size target (and often a better predictive result) for many potential therapies than can rodents [3,5].

Many previous studies have shown that gene transfer to the salivary glands can be readily and safely performed in a minimally invasive way via intra-oral cannulation of the main excretory ducts and subsequent retrograde vector delivery [6–10]. This approach has shown considerable potential for clinical utility not only for local and systemic gene therapeutics [11,12], but also for treating damaged salivary glands (e.g. post-radiation and due to autoimmunity) [13,14].

Patients who receive radiation therapy for head and neck tumors experience considerable morbidity, and a dramatic reduction in their quality of life, due to the lack of saliva [15,16]. For many such patients, with little to no response to pharmacological salivary stimuli (Radiation Therapy Oncology Group categories 2 and 3) [17], no effective treatment is available. The miniature pig parotid gland provides an excellent model for studies of salivary gland irradiation damage [18]. We have previously shown, first in rats and then in miniature pigs, that transfer of the human aquaporin-1 (hAQP1) cDNA, using a first generation serotype 5 adenoviral (Ad5) vector termed AdhAQP1, to irradiated salivary glands can lead to a transient (2–4 weeks) restoration of near-normal salivary flow [13,19]. As a result of these pre-clinical studies, the AdhAQP1 vector is now being tested in a phase 1 clinical trial (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct/show/NCT00372320?order=1).

However, to provide stable transfer and expression of the hAQP1 cDNA with irradiated salivary glands, as would be required for an ideal patient treatment, a vector other than Ad5 is needed. Retroviral vectors, such as those derived from Moloney murine leukaemia virus, are generally inappropriate for this use because cell division is required and salivary gland epithelial cells divide very slowly [20–22]. However, serotype 2 adeno-associated viral (AAV2) vectors provide stable transgene expression in several tissues [23–25], including both rodent and macaque salivary glands [8,10]. AAV2 vectors also have proven useful in some locally targeted (retina) clinical trials [26,27], but not subsequent to a systemic delivery to the liver [28].

Although we have shown that AAV2 vectors lead to stable (at least 6 months; i.e. the longest time studied) transgene expression in macaque parotid glands [10], nonhuman primates are very expensive and labour-intensive to use in studies of parotid gland irradiation damage [29,30]. Conversely, miniature pigs provide an affordable large animal model of salivary gland irradiation damage, and thus are useful in developing a clinical treatment strategy for this condition [18,19]. In the present study, for the first time, we examined the utility of AAV2 vectors to provide extended gene transfer to the parotid glands of miniature pigs.

Materials and methods

Animals

Healthy male miniature pigs (total n = 17), approximately 8 months old, weighing 25–30 kg, were obtained from the Institute of Animal Science of the Chinese Agriculture University. Animals were kept under conventional conditions with free access to water and food. Food stock (200–250 g, mixed with water) was provided twice daily, at 08.30 h and 17.00 h. The study was reviewed and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committees of Capital Medical University and the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research.

AAV2 vectors

Generation of AAV2 vectors was performed under helper-free conditions using established methods, as previously described [10,31,32]. Briefly, 293T cells were co-transfected with a trans plasmid providing the Rep and Cap genes (AAV2) and the adenoviral helper genes, and the cis plasmid containing either the human erythropoietin (hEpo) cDNA or the Escherichia coli β-galactosidase (LacZ) cDNA, flanked by the AAV2 inverted terminal repeats. Plasmids were co-transfected by calcium phosphate precipitation to generate AAV2hEpo, and AAV2LacZ, respectively. Transgene expression was driven by the Rous Sarcoma Virus promoter. Dr Y. Terada (Tokyo Medical and Dental University, Tokyo, Japan) generously provided the hEpo cDNA. The cells were harvested 48 h post-transfection and a crude viral lysate (CVL) obtained after three freeze–thaw cycles. The lysate was treated with benzonase (100 units/ml CVL; 37 °C for 45 min), adjusted to a refractive index of 1.372 by addition of CsCl, and centrifuged at 38 000 r.p.m. (182,300 g) for 65 h at 20 °C. Equilibrium density gradients were fractionated, fractions with a refractive index of 1.369–1.375 were collected, vector presence was determined by the quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR; see below), and then assayed for transducing activity in 293T cells (data not shown). After pooling appropriate fractions, vector titres were determined by qPCR. The sequences used for the forward primer, reverse primer, and probe were selected using Primer Express Primer Design software (PE Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) based on the Rous Sarcoma Virus promoter. The internal fluorogenic probe was labelled with the 6-FAM reporter dye (PE Applied Biosystems). The sequences used were: forward: 5′-TGGATTGGACGAACCACTGA-3′; reverse: 5′-TCAAATGGCGTTTATTGTATCGA-3′; probe: 5′-TTCCGCATTGCAGAGATAATTGTATTTAAGTGCCTA-3′. Vector titers were typically approximately 1012–1013 particle units (pu; vector genomes)/ml. Immediately before experiments, viral fractions were dialysed against 0.9% NaCl.

In vivo gene transfer to parotid glands

Gene transfer procedures were performed essentially as described previously [33,34]. In brief, miniature pigs were fasted (i.e. water available, but solid food withheld) for 12 h prior to performing the gene transfer. Animals were anaesthetized with a combination of ketamine chloride (6 mg/kg) and xylazine (0.6 mg/kg), placed on their side, and polyethylene tubing (Intramedic, PE10; Becton-Dickinson, Sparks, MD, USA) was used to cannulate the anterior part of the parotid (Stensen’s) duct. Atropine (0.02 mg/kg) was injected intramuscularly 30 min before cannulation. Cannulae were inserted approximately 3 cm into the orifice of the parotid duct. Vectors were suspended in infusate buffer (0.9% NaCl, pH 7.4) and delivered to one or both parotid glands by retrograde infusion. Each parotid gland received from 109 to 1011 pu of vector in an infusion volume of 4 ml, the optimal volume previously determined for this gland and species [34]. Control glands were either left untreated, 4 ml of infusion buffer alone was delivered, or AAV2LacZ was administered; all with comparable results.

Histological and immunocytochemical analysis

Following sacrifice, parotid glands were obtained from animals. Tissues were quickly removed, cleaned of extraneous tissue, cut into multiple pieces (approximately 5 × 5 × 5 mm), fixed in 10% formalin, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned at 3–4 µm. The sections were either: (i) stained with hematoxylin and eosin and examined for evidence of pathological changes (none were seen); (ii) processed for evidence of β-galactosidase activity; or (iii) processed for immunohistochemical detection of heparan sulfate proteoglycan (HSPG) [35]. The presence of β-galactosidase activity was determined by histochemical analysis using the X-Gal substrate as previously described, counterstaining with nuclear fast red [6]. For immunohistochemical detection, after blocking endogenous peroxidase, streptavidin and biotin activities (Streptavidin Biotin Blocking Kit SP-2002; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA), sections were incubated overnight at 4 °C with a primary antibody against HSPG (rat monoclonal, 05–209; Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY, USA; 1 : 150 dilution). Staining was developed using a biotinylated goat antibody (Vector Laboratories) directed against the primary antibody and the avidin–biotin peroxidase complex followed by 3,3-diaminobenzidine (SK-4100; Vector Laboratories), and then counterstained with hematoxylin. Purified rat immunoglobulin G2a and normal rabbit serum were used as negative controls.

Tissue distribution of AAV2hEpo

The distribution of AAV2hEpo after delivery to parotid glands was determined essentially as described previously [33]. Briefly, miniature pigs treated with AAV2hEpo (1011 pu) were euthanized by an air embolus introduced into the vena cava and DNA was isolated from multiple tissues (Table 1) using the DNeasy Tissue Kit from Qiagen (Chatsworth, CA, USA). DNA was quantified by absorbance at 260 nm and stored below − 15 °C. The plasmid pACCMV-hEpo was used as a standard [33], and diluted in TE buffer (10 mm Tris-Cl, pH 7.5, 1 mm ethylenediaminetetraacetate). qPCR conditions were optimized with regard to primers and probe concentration in an ABI Prism 7500HT Sequence Detection System (PE Applied Biosystems). The sequences for the forward primer, reverse primer, and probe were selected using Primer Express Primer Design software (PE Applied Biosystems) based on the coding sequence of the 579-bp hEpo cDNA. The internal fluorogenic probe was labelled with the 6-FAM reporter dye (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA, USA). The sequences used were: forward primer (hEPOTaq1; from nucleotides 354–374; 10 µm): 5′-GCAGCTGCATGTGGATAAAGC-3′; reverse primer (hEPOTaq2; from nucleotides 401–418; 10 µm): 5′-GCAGCTGCATGTGGATAAAGC-3′; and probe (hEPOTaqprobe; from nucleotides 378–399; 5 µm): 5′-/56-FAM/CAGTGGCCTTCGCAGCCTCACC/36-TSMTSp/′-3′.

Table 1.

Biodistribution of AAV2hEpo vector at 12 or 32 weeks post-administration

| Vector copies per 105 cells | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unilateral delivery | Bilateral delivery | |||

| Tissues | Targeted side | Contralateral side | Left side | Right side |

| Parotid gland | 2963 ± 187 | 12 ± 12 | 9214 ± 827 | 7809 ± 1059 |

| Submandibular gland | 37 ± 31 | 28 ± 18 | 54 ± 23 | 142 ± 70 |

| Cervical lymph nodes | 70 ± 57 | 26 ± 26 | 56 ± 40 | 145 ± 48 |

| Heart | 0 | 0 | ||

| Lung | 28 ± 26 | 70 ± 25 | ||

| Liver | 142 ± 61 | 198 ± 35 | ||

| Spleen | 110 ± 38 | 100 ± 44 | ||

| Kidney | 14 ± 14 | 23 ± 23 | 58 ± 33 | 21 ± 21 |

Data shown are the mean ± SEM. After unilateral delivery (n = 3; measured at 32 weeks) most vector copies were found in the targeted gland, with low levels of vector being distributed elsewhere. The background (for all tissues shown from one control animal) was 18 copies per 100 ng of DNA, and this value was subtracted from all data prior to calculation of vector copies/105 cells [49]. Comparable results were observed in animals that had received the AAV2hEpo vector in both parotid glands (Bilateral; n = 3; 12 weeks). Almost all vector copies were detected in the targeted parotid glands. For the heart, data were obtained from the right and left ventricles, and the septum. For the lung, data were from the right and left lung. For the liver, data were from samples of the left, right and caudal lobes. For the kidney, data were from the right and left kidney.

The qPCR assay conditions were: stage 1, 95 °C for 2 min; stage 2, 95 °C for 10 min; stage 3, 95 °C for 15 s, and then 60 °C for 1 min; repeated 40 times. This qPCR assay could detect ten vector copies per 100 ng of DNA. No control reference genes were used for these assays. qPCR assays were carried out on experimental samples in triplicate.

Collection of blood and saliva

Parotid saliva was collected, and salivary flow rates were determined, using a modified Carlson–Cittenden cup [34] on anaesthetized animals after an intramuscular injection of pilocarpine (0.1 mg/kg). Parotid saliva was collected from each parotid gland of all animals for approximately 10 min on the days indicated in the Results. Blood was obtained from the precaval vein at the same time points.

Measurement of Epo

Serum was obtained by centrifugation of blood samples at 5000 g for 2 min at room temperature. Levels of hEpo in serum and saliva were determined by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using a hEpo commercial assay kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). The lower limit of detection was 0.6 mU/ml, and assays were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Saliva and serum samples were diluted as required for accurate measurements.

Clinical laboratory analysis

Blood samples were obtained from all animals every two weeks throughout each experiment. Samples were analysed by standard clinical chemistry and hematology procedures. Serum analyses performed included calcium, potassium, sodium, chloride, phosphorous, glucose, total protein, albumin, globulin, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, lactate dehydrogenase, blood urea nitrogen, alkaline phosphatase, amylase and creatinine. Hematology included the number of white blood cells, red blood cells, platelets, hematocrit (Hct), concentration of hemoglobin, mean corpuscular volume,% lymphocytes,% monocytes and percentage granulocytes. Data at different time points were analysed using a one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s test.

Assessment of serum antibodies to hEpo

To determine whether antibodies to hEpo were present in serum samples, we evaluated all serum samples using assays similar to ones previously described [36,37]. In brief, 50 µl of standard hEpo protein (5 mU/ml) from the R&D Systems ELISA kit were incubated with miniature pig serum (or various dilutions) in a total volume 100 µl at 37 °C. These samples were then assayed using the hEpo ELISA described above. Titers are reported as the dilution of serum that resulted in 50% inhibition when measuring the hEpo protein level.

Results

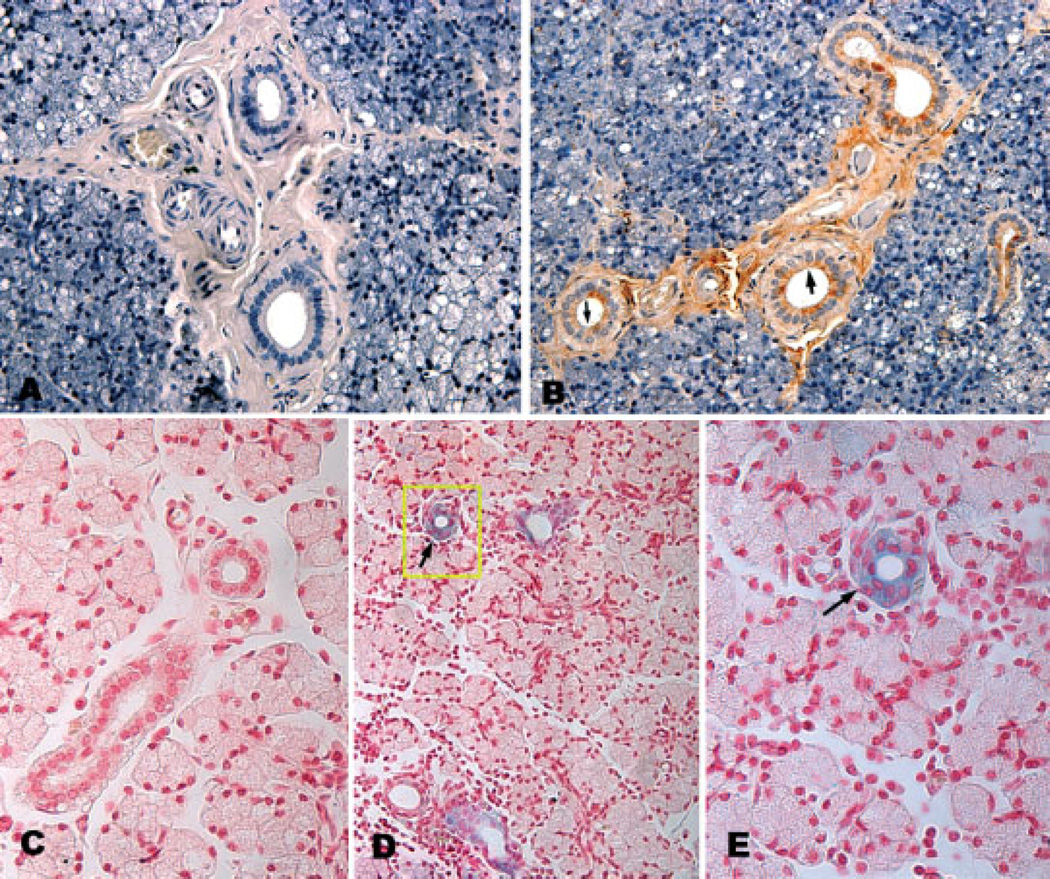

To determine whether miniature pig parotid glands expressed receptors for AAV2 on the luminal membranes of parenchymal cells (i.e. the site accessible by retrograde duct cannulation), we immunostained tissue sections with antibodies directed against HSPG. As shown in Figures 1A and 1B, luminal membranes of duct cells, but not acinar cells, react with the HSPG antibodies and immunoperoxidase staining is readily visualized. Using the AAV2LacZ vector (1011 pu/gland), we evaluated the actual cellular target for AAV2 transduction. As shown in Figures 1C to 1E, this AAV2 vector transduces duct cells in miniature pig parotid glands, consistent with the immunocytochemical localization of HSPG shown in Figure 1B, and with results reported previously for AAV2 transduction of murine salivary glands [38].

Figure 1.

Detection of HSPG and AAV2 transduction of miniature pig parotid glands. The immunodetection of HSPG is shown in (A) and (B). (A) Photomicrograph of parotid gland section used as a control for HSPG immunostaining (×200). (B) Photomicrograph of parotid gland section stained for HSPG. For details of immunostaining procedures, see Materials and methods. (B) Arrowheads point to the luminal membranes of duct cells. Note also staining for HSPG in extracellular matrix (×200). AAV2 transduction of parotid duct cells is shown in (C) to (E). AAV2LacZ was administered, or not, to miniature pig parotid glands and β-galactosidase activity was revealed by staining with X-Gal and nuclear fast red, as described in the Materials and methods. (C) Photomicrograph of a parotid gland section of a control animal showing an absence of β-galactosidase-positive staining (×400) (D) Photomicrograph of a parotid gland from a miniature pig 6 weeks after administration of 1011 pu of AAV2LacZ. The blue color indicates β-galactosidase-positive staining in duct cells (×200). (E) Higher magnification of duct from boxed area of (D) showing positive β-galactosidase activity (×400)

Production of hEpo after AAV2hEpo administration

Preliminary studies showed that the detection of hEpo after the transduction of glands was AAV2hEpo vector dose-dependent. When measured at 6 weeks post-transduction, average salivary hEpo levels, above background, were 0.5, 13 and 90 mU/ml for 109(n = 2), 1010(n = 1) and 1011(n = 2) pu/gland, respectively. Thereafter, all experiments conducted used a dose of 1011 pu/gland.

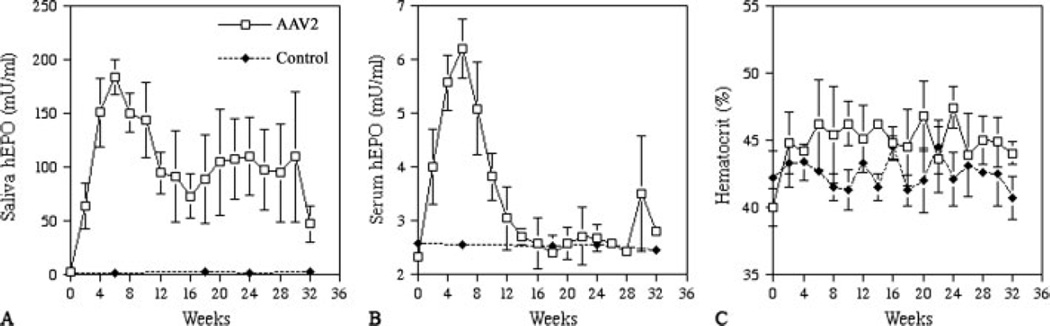

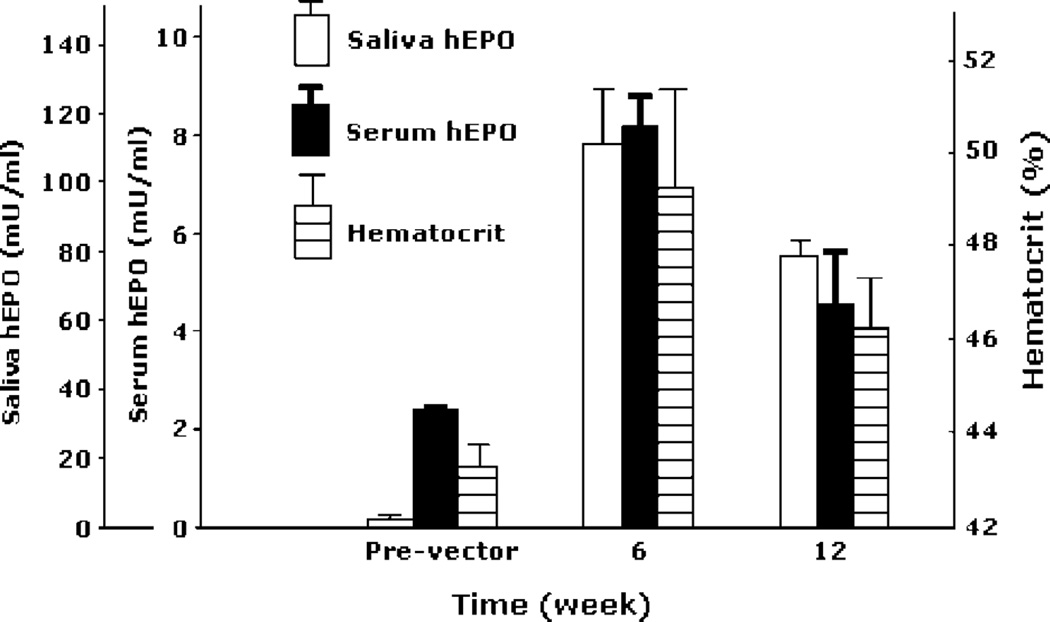

Subsequently, two cohorts of miniature pigs treated with AAV2hEpo (n = 3 per cohort) were followed. The first cohort was studied for 32 weeks (Figure 2), and animals received 1011 pu vector only to their right parotid gland. The patterns of hEpo secretion were generally similar for all animals (Figures 2A and 2B). Peak hEpo levels in saliva occurred after approximately weeks 4–8 and reached 170–200 mU/ml (Figure 2A). Thereafter, salivary hEpo levels decreased, but stayed well above background (20- to 60-fold) throughout most of the study period. At week 32, salivary hEpo levels were still more than ten-fold greater than background for all three animals. Serum hEpo levels were also significantly elevated in these experiments (Figure 2B). After transduction, serum hEpo rose in all animals, with peak levels (approximately 6 mU/ml) being observed at weeks 4–8. Serum hEpo, however, returned to background levels at weeks 12–20 and remained at these levels until the end of the study. Hcts were elevated in all animals within 6 weeks (>10% pre-vector values), and they remained elevated throughout the study (Figure 2C). The second cohort of miniature pigs was administered the AAV2hEpo vector to both parotid glands and was followed for 12 weeks (Figure 3). The average hEpo levels measured in parotid saliva from both glands were generally similar to those shown in Figure 2, as were the serum Epo levels. All animals showed elevated Hcts from approximately week 4 until the end of the study (Figure 3). Additionally, all treated animals, in both cohorts, exhibited low levels of anti-hEpo antibodies in their serum (Figure 4). The anti-hEpo antibodies were first detected at week 8 and remained generally low throughout both studies. The maximal titer measured in any animal was 1 : 16.

Figure 2.

Time course of human erythropoietin (hEpo) detection and hematocrit values in miniature pigs after parotid gene transfer. (A) Average salivary hEpo levels over the 32-week experimental time for animals transduced with AAV2hEpo (n = 3) or not (controls, n = 3). (B) Average serum hEpo levels over the 32-week experimental time for animals transduced with AAV2hEpo or not (controls). (C) Average hematocrit values for transduced and control animals over the experimental time course. Data shown are the mean ± SD. At some control time-points, the SD values are smaller than the size of the symbol used

Figure 3.

Detection of hEpo in saliva and serum, as well as hematocrit levels, of miniature pigs in the last experimental cohort. Data shown are the mean ± SEM for samples prior to vector administration (Pre-vector; time ‘0’), 6 weeks after vector administration, and 12 weeks after vector administration

Figure 4.

Scattergram of serum anti-hEpo antibody levels in miniature pigs from the last two experimental cohorts. Data shown are from individual animals at three times after vector administration; weeks 2, 12 and 32 (only for one cohort). Each symbol represents a separate animal. Miniature pigs treated with AAV2hEpo are indicated by filled symbols and control animals (glands infused with buffer or AAV2LacZ) are indicated by open symbols. Unilateral refers to animals receiving vector in only one parotid gland, whereas animals designated as bilateral were administered vector to both parotid glands

Distribution of AAV2hEpo after administration to parotid glands

We first evaluated the biodistribution of the AAV2hEpo vector 32 weeks after administration of 1011 pu to single parotid glands in animals from the first cohort. As shown in Table 1, most of administered vector (>85%) was found in the targeted right parotid gland. Trace amounts of vector were found similarly distributed, and at very low levels, in several adjacent tissues (contralateral parotid gland, submandibular glands, cervical lymph nodes) and some distant sites (heart, liver and lung). Next, we conducted similar evaluations of animals 12 weeks after they had received the AAV2hEpo vector to both parotid glands (Table 1). The results were quite comparable, in that the vast majority (>95%) of vector was detected in both targeted parotid glands.

Effect of AAV2hEpo administration on serum chemistry and hematology

As shown in Tables 2 and 3, few alterations in clinical laboratory parameters resulted from AAV2 vector delivery to parotid glands of miniature pigs. For example, there were no changes in clinical chemistry values after AAV2 vector administration at all time points; essentially, all were within normal limits over the 32-week period studied. There were a few differences in hematology values (Table 3). A transient elevation in white blood cells was seen at week 2, although this was not statistically significant and returned to normal values by the 4-week measurement. Additionally, significant elevations in hemoglobin and Hct values were seen after vector delivery, consistent with the biological activity of the transgene used. Similar results were observed in animals that received vector in both parotid glands (data not shown).

Table 2.

Serum chemistry values before and at weeks 2, 12 and 32 after AAV2hEpo administration

| Component (units) |

Pre-treatment | Week 2 | Week 12 | Week 32 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALT (IU/l) | 41.66 ± 3.51 | 38.67 ± 7.37 | 41.67 ± 2.52 | 37.33 ± 5.03 |

| AST (IU/l) | 44.33 ± 7.09 | 41.67 ± 6.03 | 36.67 ± 8.02 | 36.0 ± 3.00 |

| ALP (IU/l) | 71.33 ± 6.42 | 76.67 ± 4.51 | 75.00 ± 6.24 | 69.33 ± 8.73 |

| TP (g/l) | 72.33 ± 6.42 | 72.33 ± 5.03 | 73.33 ± 8.74 | 71.00 ± 5.29 |

| ALB (g/l) | 40.66 ± 2.31 | 42.33 ± 3.05 | 41.33 ± 1.16 | 41.33 ± 0.58 |

| GLB (g/l) | 39.66 ± 3.21 | 38.67 ± 1.15 | 43.00 ± 5.29 | 41.00 ± 0.00 |

| A/G, albumin: globulin ratio | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.10 ± 0.10 | 0.96 ± 0.15 | 1.00 ± 0.00 |

| LDH (IU/l) | 309 ± 98 | 374 ± 54 | 339.7 ± 16.0 | 279.67 ± 21.54 |

| Glu (mmol/l) | 4.50 ± 0.26 | 4.60 ± 0.44 | 4.60 ± 0.61 | 4.17 ± 0.21 |

| BUN (mmol/l) | 3.30 ± 0.60 | 3.37 ± 0.95 | 4.53 ± 0.31 | 3.93 ± 0.74 |

| CO2 (mmol/l) | 26.76 ± 1.58 | 28.33 ± 1.86 | 28.83 ± 1.14 | 23.63 ± 2.84 |

| CREA (ummol/l) | 67.50 ± 4.80 | 61.60 ± 2.51 | 75.47 ± 4.34 | 65.47 ± 5.04 |

| Ca2+ (mmol/l) | 2.49 ± 0.19 | 2.39 ± 0.06 | 2.41 ± 0.13 | 2.34 ± 0.06 |

| P, phosphorus (mmol/l) | 2.36 ± 0.06 | 2.37 ± 0.17 | 2.38 ± 0.1 | 2.34 ± 0.09 |

| Na+ | 138.7 ± 2.1 | 137.0 ± 2.6 | 140.7 ± 3.2 | 137 ± 3.0 |

| K+ (mmol/l) | 3.68 ± 0.12 | 3.89 ± 0.17 | 3.74 ± 0.07 | 3.95 ± 0.27 |

| CI− (mmol/l) | 100.3 ± 2.5 | 100.0 ± 1.0 | 100.7 ± 1.5 | 102 ± 2.6 |

| AMY (IU/l) | 2296 ± 98 | 2006 ± 310 | 2014 ± 293 | 2058 ± 77 |

Data shown are the mean ± SD for three miniature pigs. There were no significant differences at weeks 2, 12 and 32 compared to pre-treatment. ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; TP, total protein; ALB, albumin; GLB, globulin; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; Glu, glucose; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; CREA, creatinine; AMY, amylase.

Table 3.

Haematology values before and at weeks 2, 12 and 32 after AAV2hEpo administration

| Component (units) |

Pre-treatment | Week 2 | Week 12 | Week 32 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBC (109/l) | 11.81 ± 2.11 | 16.22 ± 0.92 | 12.69 ± 1.40 | 13.17 ± 1.99 |

| RBC (1012/l) | 7.2 ± 0.52 | 7.79 ± 0.73 | 7.97 ± 0.38 | 8.36 ± 0.59 |

| HGB (G/l) | 121.33 ± 3.05 | 125.67 ± 3.05 | 134.67 ± 6.35 | 136.33 ± 6.65 |

| HCT (%) | 40.0 ± 1.70 | 44.77 ± 2.80 | 45.07 ± 3.08 | 44.0 ± 1.06 |

| PLT (109/l) | 293.4 ± 78.88 | 333.67 ± 104.5 | 320.67 ± 89.1 | 296.7 ± 28.15 |

| PCT (%) | 0.19 ± 0.02 | 0.18 ± 0.02 | 0.22 ± 0.07 | 0.18 ± 0.03 |

| MCV (FL) | 54.14 ± 4.62 | 52.07 ± 3.15 | 54.67 ± 4.21 | 52.37 ± 3.07 |

| MCH (PG) | 16.97 ± 1.67 | 17.41 ± 0.50 | 16.63 ± 1.90 | 17 ± 1.85 |

| MCHC (G/l) | 305.33 ± 12.85 | 307.67 ± 19.73 | 306.67 ± 12.50 | 315.67 ± 12.86 |

| RDW (%) | 14.64 ± 1.28 | 14.53 ± 0.84 | 16.03 ± 0.42 | 15.73 ± 0.85 |

Data shown are the mean ± SD for three miniature pigs. For WBC, F = 3.927, P = 0.054. For hemoglobin, F = 6.110, P = 0.018; week 12 and week 32 > pre-treatment and week 2 (P < 0.05 for both). For hematocrit, F = 8.645, P = 0.013, weeks 2, 12 and 32 > pre-treatment (P < 0.05 for all). WBC, white blood cell count; RBC, red blood cell count; HGB, hemoglobin; HCT, hematocrit; PLT, platelet; PCT, plateletcrit; MCV, mean corpuscular volume; MCH, mean corpuscular hemoglobin; MCHC, mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration; RDW, red cell distribution width.

Discussion

The present study was designed to examine the ability of AAV2 vectors to mediate extended transgene expression in miniature pig parotid glands. AAV2 vectors enable long-term transgene expression in the salivary cells of both mice and macaques [8,10]. Previously, we have shown that the miniature pig is a valuable and affordable large animal model (approximately 40–50% by weight of adult humans) for studies using Ad5 vector-mediated gene transfer to correct salivary gland radiation damage [18,19]. For example, in the present studies, 17 animals were utilized; a number that would be impossible for us to study if macaques were used because of the expense. Irrespective of the animal model, for gene transfer to be practical clinically for this condition, extended transgene (months to years) expression is required.

In the present study, we have shown that parotid glands of miniature pigs have receptors (HSPG) on their duct cell luminal membranes for AAV2 (i.e. the same cell type transduced by an AAV2 vector encoding β-galactosidase). Earlier studies by us in mouse and macaque salivary glands have demonstrated that AAV2, vectors lead to stable transgene expression [8,10]. Subsequent to preliminary time course and dose–response studies, we followed two miniature pig cohorts (three vector-treated animals each) in more detail for either 12 or 32 weeks. Studies with both cohorts yielded similar results. Interestingly, unlike the results obtained after AAV2 transduction of salivary glands in both mice and macaques, transgene detection in miniature pigs decreased steadily after achieving peak values. For example, by the end of the longest time point studied (32 weeks), salivary hEpo production from transduced glands had declined by approximately 75% from peak values. Low levels of anti-hEpo antibodies were detected in the serum of all treated animals, and it is possible that they partly contributed to the decline in hEpo measurements observed. Importantly, the decreased hEpo expression was not accompanied by any increase in serum amylase activity, making it unlikely that the parotid gland was a significant target of cytotoxic lymphocyte (CTL)-mediated destruction, as has been observed for transduced hepatocytes after AAV2 transduction in a recent clinical trial [28]. Furthermore, and importantly, in the study by Mingozzi et al. [28] CTL-mediated responses occurred at vector doses >2 × 1012 pu/kg, whereas, in the present study, our highest total dose delivered (2 × 1011 pu total in the two parotid glands; last cohort) is equivalent to approximately 3.3 × 109 pu/kg (i.e. a markedly lower dose).

In addition, as previously shown after the transduction of miniature pig parotid glands with an Ad5 vector encoding hEpo [33] that transduces both acinar and duct cells, transgenic hEpo protein secretion in the present study was overwhelmingly in an exocrine direction (i.e. into saliva versus into the bloodstream). This hEpo sorting behaviour is quite different from that observed after hEpo cDNA transfer to salivary glands in mice and macaques [38,39] and most likely is attributable to genetic and/or metabolic differences in key sorting molecules necessary for hEpo recognition and routing within the miniature pig parotid cells [40,41].

Interestingly, for two of the experimental animals in the 32-week cohort, salivary hEpo levels fluctuated considerably after peak expression was achieved (approximately 50%), and approached near peak levels (approximately 85%) as late as week 30. However, salivary hEpo detection in the other animal declined from a peak value at week 6, to fairly stable lower levels (approximately 20% maximum) from week 14 until the end of the study. Overall, this type of kinetic pattern, especially the long-lived detection of hEpo in saliva, is unlikely to be related to gene or promoter silencing, which nevertheless would be unexpected because the same AAV2 vector led to expression for approximately 1 year in mice [8] and approximately 6 months in macaques [10]. Additionally, the diminished and fluctuating serum hEpo levels are unlikely to be related to serum antibody interference with the ELISA used because only very low levels of anti-hEpo antibodies were detected (≤1 : 16) (Figure 4). However, because the AAV2 vector should exist in an episomal location in salivary glands [8], it is conceivable that duct cell turnover during the course of these experiments partly contributed to the reduced hEpo detection over time. In rodent salivary glands, the turnover of epithelial cells has been well studied and is extremely low, with the average lifespan of these cells being at least 125–200 days [22,42,43]. Although it is reasonable to assume a generally similar lifespan for epithelial cells in the salivary glands of miniature pigs, there are no data available regarding salivary cell turnover in this or any other higher animal species.

Whatever the reason, AAV2-mediated transgene expression in the miniature pig parotid gland, although long-lived, does decrease over time. However, given the impetus for the present study, it is clear that AAV2 vectors can be useful for mediating a much longer (6–8 months versus 2–4 weeks), although not ideal, transgene expression for the correction of salivary gland radiation damage with hAQP1 gene transfer than has been achieved by an Ad5 vector in the miniature pig model [19]. This extended length of hAQP1 transgene expression will allow the study of treated miniature pigs for significant time periods after hAQP1 gene transfer, permitting the examination of several relevant clinical concerns (e.g. whether anti-hAQP1 antibodies are generated and whether long-term hAQP1 expression improves food consumption and facilitates weight gain). Additionally, it should be possible to extend levels of hAQP1 transgene expression beyond 6–8 months by re-administering the transgene via other AAV vector serotypes [44–46]. Althoguh it is hard to predict what will occur after AAV2 vector transduction of human salivary glands, carrying out long-term hAQP1 gene transfer studies in this large animal model should considerably facilitate eventual clinical applications.

The results of the present study are also consistent with earlier studies of AAV2 vector delivery to salivary glands of mice and macaques (i.e. it is well tolerated) [10,47], This conclusion is supported by the results obtained in many hematological and serum chemical analyses showing no consistent negative changes for any parameter measured. Second, the biodistribution data presented here for male miniature pigs indicate that AAV2 vector was primarily localized in the targeted parotid gland, as also shown in previous studies with both male mice and macaques [8,10,47]. Little vector (i.e. just above background levels) was detected at sites beyond the oral cavity, in keeping with the notion that salivary gland delivery provides a safe and fairly restricted target site for AAV2 (and Ad5) [9] vectors.

In summary, the present study demonstrates that AAV2hEpo vector can mediate extended hEpo expression in the miniature pig parotid gland. However, hEpo transgene expression was not as stable in this large animal model as that observed in mice and rhesus macaques after gland transduction with this same vector. Nonetheless, our results support the idea of extending pre-clinical studies in miniature pigs with AAV2 vectors, such as that encoding hAQP1 [48], to determine whether it is possible to restore salivary flow long-term in radiation-damaged salivary glands. However, the present studies also demonstrate that the parotid glands of miniature pigs are unlikely to be a useful large animal model for studying the application of gene therapeutics to salivary glands because of the highly unusual sorting observed with hEpo (i.e. overwhelmingly into saliva) compared to the sorting results obtained with hEpo in mice and macaques.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant 30430690), Beijing Major Scientific Program Grant (D0906007000091), the National Special Foundation for Excellent PhD (Paper no. 200778), and by the Division of Intramural Research of the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research.

References

- 1.Ferber D. Gene therapy: safer and virus free? Science. 2001;294:1638–1642. doi: 10.1126/science.294.5547.1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trobridge G, Beard BC, Kiem HP. Hematopoietic stem cell transduction and amplification in large animal models. Hum Gene Ther. 2005;16:1355–1366. doi: 10.1089/hum.2005.16.1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Casal M, Haskins M. Large animal models and gene therapy. Eur J Hum Genet. 2006;14:266–272. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fabre JW, Grehan A, Whitehorne M, et al. Hydrodynamic gene delivery to the pig liver via an isolated segment of the inferior vena cava. Gene Ther. 2008;15:452–462. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3303079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.High K. Gene transfer for hemophilia: can therapeutic efficiency in large animals be safely translated to patients. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3:1682–1691. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01460.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mastrangeli A, O’Connell B, Aladib W, et al. Direct in vivo adenovirus-mediated gene transfer to salivary glands. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:G1146–G1155. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1994.266.6.G1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.He X, Goldsmith CM, Marmary Y, et al. Systemic action of human growth hormone following adenovirus-mediated gene transfer to rat submandibular glands. Gene Ther. 1998;5:537–541. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Voutetakis A, Kok MR, Zheng C, et al. Reengineered salivary glands are stable endogenous bioreactors for systemic gene therapeutics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:3053–3058. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400136101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zheng C, Goldsmith CM, Mineshiba F, et al. Toxicity and biodistribution of a first-generation recombinant adenoviral vector, encoding aquaporin-1, after retroductal delivery to a single rat submandibular gland. Hum Gene Ther. 2006;17:1122–1133. doi: 10.1089/hum.2006.17.1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Voutetakis A, Zheng C, Mineshiba F, et al. Adeno-associated virus serotype 2-mediated gene transfer to the parotid glands of nonhuman primates. Hum Gene Ther. 2007;18:142–150. doi: 10.1089/hum.2006.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang J, Voutetakis A, Zheng C, Baum BJ. Rapamycin control of exocrine protein levels in saliva after adenoviral-mediated gene transfer. Gene Ther. 2004;11:729–733. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang J, Voutetakis A, Papa M, et al. Rapamycin control of transgene expression from a single AAV vector in mouse salivary glands. Gene Ther. 2006;13:187–190. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Delporte C, O’Connell BC, He X, et al. Increased fluid secretion after adenoviral-mediated transfer of the aquaporin-1 cDNA to irradiated rat salivary glands. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3268–3273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kok MR, Yamano S, Lodde BM, et al. Local adeno-associated virus-mediated interleukin 10 gene transfer has disease-modifying effects in a murine model of Sjogren’s syndrome. Hum Gene Ther. 2003;14:1605–1618. doi: 10.1089/104303403322542257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nagler RM, Baum BJ. Prophylactic treatment reduces the severity of xerostomia following irradiation therapy for oral cavity cancer. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129:247–250. doi: 10.1001/archotol.129.2.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vissink A, Jansma J, Spijkervet FK, et al. Oral sequelae of head and neck radiotherapy. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2003;14:199–212. doi: 10.1177/154411130301400305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cox JD, Steitz J, Pajak TF. Toxicity criteria of the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) and the European Organization for research and treatment of cancer. Int J Radiation Oncology Biol Phys. 1995;31:1341–1346. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(95)00060-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li J, Shan Z, Ou G, et al. Structural and functional characteristics of irradiation damage to parotid glands in the miniature pig. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;62:1510–1516. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shan Z, Li J, Zheng C, et al. Increased fluid secretion after adenoviral-mediated transfer of the human aquaporin-1 cDNA to irradiated miniature pig parotid glands. Mol Ther. 2005;11:444–451. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barka T, van der Noen HM. Retrovirus-mediated gene transfer into salivary glands in vivo. Hum Gene Ther. 1996;7:613–618. doi: 10.1089/hum.1996.7.5-613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shai E, Falk H, Honigman A, Panet A, Palmon A. Gene transfer mediated by different viral vectors following direct cannulation of mouse submandibular glands. Eur J Oral Sci. 2002;110:254–260. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0722.2002.21200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Redman RS. Proliferative activity by cell type in the developing rat parotid gland. Anat Rec. 1995;241:529–540. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092410411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mount JD, Herzog RW, Tillson DM, et al. Sustained phenotypic correction of hemophilia B dogs with a factor IX null mutation by liver-directed gene therapy. Blood. 2002;99:2670–2676. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.8.2670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Auricchio A, O’Connor E, Weiner D, et al. Noninvasive gene transfer to the lung for systemic delivery of therapeutic proteins. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:499–504. doi: 10.1172/JCI15780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kay MA, Glorioso JC, Naldini L. Viral vectors for gene therapy: the art of turning infectious agents into vehicles of therapeutics. Nat Med. 2001;7:33–40. doi: 10.1038/83324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bainbridge JWB, Smith AJ, Barker SS, et al. Effect of gene therapy on visual function in Leber’s congenital amaurosis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2231–2239. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maguire AM, Simonelli F, Pierce EA, et al. Safety and efficacy of gene transfer for Leber’s congenital amaurosis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2240–2248. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mingozzi F, Maus MV, Hui DJ, et al. CD8+ T-cell responses to adeno-associated virus capsid in humans. Nat Med. 2007;13:419–422. doi: 10.1038/nm1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O’Connell AC, Baccaglini L, Fox PC, et al. Safety and efficacy of adenovirus-mediated transfer of the human aquaporin-1 cDNA to irradiated parotid glands of non-human primates. Cancer Gene Ther. 1999;6:505–513. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baum BJ, Zheng C, Cotrim AP, et al. Transfer of the AQP1 cDNA for the correction of radiation-induced salivary hypofunction. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1758:1071–1077. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2005.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chiorini JA, Wendtner CM, Urcelay E, et al. High-efficiency transfer of the T cell co-stimulatory molecule B7–2 to lymphoid cells using high-titer recombinant adeno-associated virus vectors. Hum Gene Ther. 1995;6:1531–1541. doi: 10.1089/hum.1995.6.12-1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaludov N, Handelman B, Chiorini JA. Scalable purification of adeno-associated virus serotypes 2, 4, or 5 using ion exchange chromatography. Hum Gene Ther. 2002;13:1235–1243. doi: 10.1089/104303402320139014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yan X, Voutetakis A, Zheng C, et al. Sorting of transgenic secretory proteins in miniature pig parotid glands following adenoviral-mediated gene transfer. J Gene Med. 2007;9:779–787. doi: 10.1002/jgm.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li J, Zheng C, Zhang X, et al. Developing a convenient large animal model for gene transfer to salivary glands in vivo. J Gene Med. 2004;6:55–63. doi: 10.1002/jgm.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Summerford C, Samulski RJ. Membrane-associated heparan sulfate proteoglycan is a receptor for adeno-associated virus type 2 virions. J Virol. 1998;72:1438–1445. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.2.1438-1445.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sprangers MC, Lakhai W, Koudstaal W, et al. Quantifying adenovirus-neutralizing antibodies by luciferase transgene detection: addressing pre-existing immunity to vaccine and gene therapy vectors. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:5046–5052. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.11.5046-5052.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zheng C, Vitolo JM, Zhang W, et al. Extended transgene expression from a nonintegrating adenoviral vector containing retroviral elements. Mol Ther. 2008;16:1089–1097. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Voutetakis A, Bossis I, Kok MR, et al. Salivary glands as a potential gene transfer target for gene therapeutics of some monogenetic endocrine disorders. J Endocrinol. 2005;185:363–372. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.06171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Voutetakis A, Zheng C, Metzger M, et al. Sorting of transgenic secretory proteins in rhesus macaque parotid glands following adenoviral mediated gene transfer. Hum Gene Ther. 2008;19:1401–1406. doi: 10.1089/hum.2008.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fölsch H, Ohno H, Bonifacino JS, Mellman I. A novel clathrin adaptor complex mediates basolateral targeting in polarized epithelial cells. Cell. 1999;99:189–198. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81650-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cosen-Binker LI, Lam PP, Binker MG, et al. Alcohol/cholecystokinin-evoked pancreatic acinar basolateral exocytosis is mediated by protein kinase C alpha phosphorylation of Munc18c. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:13047–13058. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611132200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Denny PC, Ball WD, Redman RS. Salivary glands: a paradigm for diversity of gland development. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1997;8:51–75. doi: 10.1177/10454411970080010301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zajicek G, Schwartz-Arad D, Arber N, Michaeli Y. The streaming of the submandibular gland II: parenchyma and stroma advance at the same velocity. Cell Tissue Kinet. 1989;22:343–348. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.1989.tb00219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Halbert CL, Rutledge EA, Allen JM, et al. Repeat transduction in the mouse lung by adeno-associated virus vectors with different serotypes. J Virol. 2000;74:1524–1532. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.3.1524-1532.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kok MR, Voutetakis A, Yamano S, et al. Immune responses following salivary gland administration of recombinant adeno-associated serotype 2 vectors. J Gene Med. 2005;7:432–441. doi: 10.1002/jgm.678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Riviere C, Danos O, Douar AM. Long-term expression and repeated administration of AAV type 1, 2 and 5 vectors in skeletal muscle of immunocompetent adult mice. Gene Ther. 2006;13:1300–1308. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Voutetakis A, Zheng C, Wang J, et al. Gender differences in serotype 2 adeno-associated virus biodistribution after administration to rodent salivary glands. Hum Gene Ther. 2007;18:1109–1118. doi: 10.1089/hum.2007.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Braddon VR, Chiorini JA, Wand S, et al. Adenoassociated virus-mediated transfer of a functional water channel into salivary epithelial cells in vitro and in vivo. Hum Gene Ther. 1998;9:2777–2785. doi: 10.1089/hum.1998.9.18-2777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee GM, Thornwaite JT, Rasch EM. Picogram per cell determination of DNA by flow cytofluorometry. Analyt Biochem. 1984;137:221–226. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(84)90374-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]