Abstract

Background

Homebound older adults have significant multi-morbidity, disability, and difficulty accessing care- traits that would suggest a high mortality rate. Yet, the association between homebound status and mortality is uncertain.

Design, Settings and Participants

The study sample consisted of 6,400 older adults from the National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS) interviewed between 2011 and 2013. NHATS is a nationally representative sample of Medicare beneficiaries ages 65 and older who complete annual, in-person interviews on late-life function and disability.

Measurements

We described two-year mortality rates and the prevalence of homebound status in the year prior to death using three categories of homebound status- homebound (never or rarely left home in the last month), semihomebound (only left home with assistance, needed help or had difficulty) and nonhomebound (left home without help or difficulty).

Results

In unadjusted analyses, two-year mortality was 40.3% in the homebound, 21.3% in the semihomebound and 5.8% in the nonhomebound. Homebound status was associated with increased two-year mortality, adjusted for sociodemographics, comorbidities and functional status (hazard ratio (HR), 2.08; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.63-2.65, p<.001). Half (50.9%) of older community-dwelling Medicare beneficiaries were homebound in the year prior to death.

Conclusion

Homebound status is associated with an increased risk of death independent of functional impairment and comorbidities. In order to improve outcomes for homebound older adults and the many older adults who will become homebound in the last year of life, providers and policymakers need to extend healthcare services from hospitals and clinics to the homes of vulnerable patients.

Keywords: Homebound, United States/epidemiology, cross-sectional studies, mortality

INTRODUCTION

A combination of multi-morbidity, functional impairment, and inadequate social support confine an estimated two million older adults to their homes.1, 2 While definitions of homebound status vary, all are based on the concept that homebound individuals have difficulty leaving home to access office-based care.2 Yet, they have significant medical needs with an average of five chronic diseases and dependence in at least one self-care activity, such as bathing or dressing.1, 3 Although it is well-known that these levels of multi-morbidity and functional impairment are associated with increased mortality,4, 5 the excess risk of death directly attributable to homebound status is uncertain.

An accurate estimate of mortality in the homebound status has critical population health, clinical, and research implications. First, policymakers can use population-level data regarding homebound status and mortality to estimate the impact and duration of population health programs, such delivering long-term services and supports. This same information can be used by homebound older adults, their caregivers and providers in planning for future medical and caregiving needs.6 Second, understanding the association between homebound status and mortality will provide an estimate of the number of older adults who have difficulty accessing office-based care at the end of life.7 This knowledge would influence the demand for models of care, such as home-based primary and palliative care, designed to bring primary care to the homes of individuals with multi-morbidity and functional impairment.8-10 Lastly, this knowledge would be an important first step in conceptualizing homebound status as distinct from functional status in predicting mortality in older adults.

The epidemiology of homebound status and related health outcomes in the United States, including mortality, has been limited by homebound definitions that were based on the utilization of Medicare skilled home health services, rather than estimates of patients’ frequency of leaving home.2 As a result, the best available prognostic information about homebound status comes from international populations and single US practices. Two-year mortality estimates range from 17-42% in home-based primary care practices in the US and Brazil to 23-40% in nationally representative surveys of community-dwelling older adults in France, Israel and Brazil.9, 11-14

The National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS), a nationally representative cohort of older adults in the United States now affords the opportunity to relate homebound status to mortality.15, 16 The aims of this study were to use NHATS data (1) to determine the impact of homebound status on two-year mortality and (2) to describe the prevalence of homebound status in the year prior to death among older adults in the United States.

METHODS

Study Sample

The study sample included participants from the National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS), a nationally representative cohort of adults aged 65 and over designed to investigate trends and dynamics in late-life functioning.16, 17 NHATS participants were selected from the Medicare enrollment file, the national insurance of 93% of older adults in the United States.18 NHATS is following a cohort of 8,245 Medicare beneficiaries (71.3% weighted response rate and 87.4% retention at round 3) residing in the contiguous United States with annual, in-person interviews and purposely oversampled non-Hispanic Blacks and those over age 90. In-person interviews of participants residing in settings other than nursing homes include collection of self-reported self-care and household activities, living arrangement and economic status. Proxies are interviewed when the participant is not available. This study included data from NHATS rounds one, two and three, collected from 2011-2013. The NHATS study protocol was approved by The Johns Hopkins University Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Homebound status

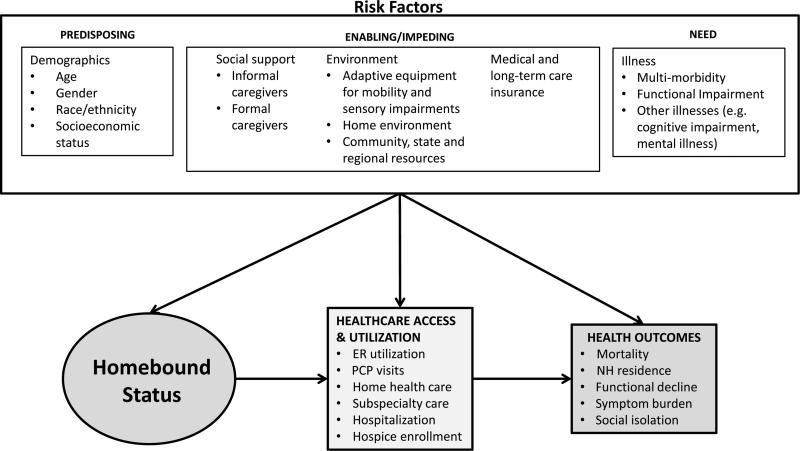

We conceptualized homebound status using Aday and Anderson's Behavioral Model of Health Services Use19 and gerontological frameworks for the study of disability (Figure 1).15, 20 By convention, predisposing factors are the often poorly mutable traits, such age, race and socioeconomic status, that impact health. Enabling factors, such as health insurance, are potentially modifiable. Need represents the specific illnesses that cause a person to seek healthcare. Together, predisposing, enabling and need factors contribute in an additive fashion to health services utilization and health outcomes. Within this framework, we conceptualized homebound status as the cumulative effect of multi-morbidity, functional impairment, social support and environmental resources that make it difficult to leave home to access appropriate care, altering healthcare utilization patterns and contributing to poor outcomes.21

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework for Homebound Status and Poor Health Outcomes

We defined homebound status using previously published responses to NHATS questions in a two-stage process.1 The first stage was based on the frequency of a person leaving his or her home. Participants were asked, “How often did you go out in the last month?” Participants who responded never or rarely (≤1 day/week) were defined as homebound. In stage two, those who responded some days (2-4 days/week), most days (5-6 days/week) or every day were categorized as semihomebound or nonhomebound in response to the following two questions: “Did anyone ever help you out?” and “How much difficulty did you have leaving the house by yourself?” Those who responded that they did receive help going out or that that they had a lot, some or a little difficulty leaving the house by themselves were defined as semihomebound. Participants who neither received help nor had any difficulty leaving home alone were defined as nonhomebound.

Outcomes

The primary outcome of the study was two-year mortality. The participant's death was reported by informants during attempts to contact the participant for the annual interview. In addition to two-year mortality, we also reported homebound status and nursing home placement at two-years. Lastly, we looked retrospectively at all deaths over two years and described homebound status in the year prior to death.

Covariates

We assessed need, enabling, and predisposing factors independently associated with homebound status and mortality.

Need Factors

We included specific chronic diseases as well as the number of comorbidities in our analysis. Chronic diseases were reported in response to the question, “Has a doctor ever told you that you have” any of the following conditions: heart attack, heart disease, high blood pressure, arthritis, osteoporosis, diabetes, lung disease, stroke, dementia/Alzheimer's disease, cancer, and hip fracture. The number of chronic diseases also included depression and anxiety. We defined depression using the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2), a commonly used screening tool in which participants are asked the frequency with which they have felt (1) little interest or pleasure in doing things and (2) down, depressed or hopeless. The PHQ-2 score ranges from 0-6 with a score ≥3 denoting possible depression.22 Similarly, we defined anxiety using a previously established cut-off for the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-2 (GAD-2) screening tool.23 Participants provided the frequency with which they have been bothered by (1) feeling nervous, anxious or on edge and (2) not being able to stop or control worrying. Scores ranged from 0-6, where ≥3 denotes possible anxiety.23 Participants were also asked if they have been hospitalized in the last year and the number of hospitalizations.

Dementia was defined as probable, possible, or no dementia based on a combination of self-report and cognitive testing.24 Cognitive testing included evaluations of memory (immediate and delayed recall), orientation, and executive function, and was administered to participants who completed their own interviews, as well as half of participants whose interviews were completed by a proxy. Probable dementia included (1) report by the participant or the proxy that he/she had been told by a doctor that the participant had dementia, (2) a score of ≥2 on the AD8, an 8-item instrument administered to proxies that assesses the participant's memory, temporal orientation, judgment and function25 or (3) ≤1.5 standard deviations below the mean in at least two domains of the cognitive battery. Possible dementia was defined as ≤1.5 standard deviations below the mean in one domain of the cognitive battery. No dementia included participants who had never been told by a doctor that they have dementia and whose proxies scored <2 on the AD8 and/or the participant scored >1.5 standard deviations above the mean on the cognitive battery.

Functional impairment was measured by self-reported self-care and household.26, 27 Self-care activities included eating, bathing, toileting, dressing and transferring. Dependence in the self-care activities was defined as needing help from another person in the last month. We defined dependence in household activities as needing help from another person in the last month with laundry, shopping, preparing hot meals, bills and banking, or managing medications.

Enabling Factors

Enabling factors included social support and the presence of medical and long-term care insurance. Social support was measured by including self-reported marital status, living arrangement (alone or with others), and the presence of helpers. Helpers included formal and informal caregivers who helped in the last month with a self-care activity, household activity, mobility activity (helping them get around inside or outside of the home) or a medical care-related activity (sitting in with the participant during a medical appointment or help making medical insurance decisions). All participants in the study had Medicare insurance. However, we included Medicaid health insurance and ownership of long-term care insurance, described as “an insurance that would pay for a year of more of care in a nursing home, assisted living or in your home”. Environmental factors, such as the presence of stairs or adaptive equipment for mobility and sensory impairments, while related to homebound status, have not been shown to be related to survival and were not included in this analysis.

Predisposing Factors

Sociodemographic information included self-reported age, gender, race and ethnicity, and measures of socioeconomic status, specifically education and income.

Data analysis

Analyses were weighted to account for differential probabilities of selection into the NHATS sample and to adjust for potential nonresponse bias.28-30 Thus, analytic weights were used to calculate prevalence estimates and standard errors. Demographics, social support, insurance, comorbidities and functional measures were compared according to homebound status using t-tests and chi-squared analyses with the nonhomebound as the reference group. We generated a Kaplan-Meier curve to describe differences in mortality according to homebound status. We then used three Cox proportional hazards models to test the impact of homebound status on mortality. These included a base model of homebound status, a model of homebound status adjusted for demographics, and a model of homebound status adjusted for demographics, social support, insurance, comorbidities and function. Confounders in the final multivariable model included: age, gender, race, income, living arrangement, number of chronic diseases, dementia, depression, and dependence in self-care and household activities. We used descriptive statistics to calculate two year outcomes, including homebound status, nursing home residence and death, as well as the prevalence of homebound status in the year prior to death. Data management and statistical analyses were completed using SAS version 9.4.

RESULTS

Of the 7,609 community-dwelling participants who completed a baseline interview, 15% (n=1138) were excluded because they were lost to follow-up for the second interview and an additional 1% (n=71) was excluded because they had incomplete data to define homebound status. The final analytic sample was 6,400. Proxy respondents completed 7% (n=476) of baseline interviews. Participants were 7.5% homebound (n=481), 18% semihomebound (n=1,157) and 73.8% (n=4,726) nonhomebound.

Homebound and semihomebound participants differed from the nonhomebound on almost all measures of demographics, social support, comorbidities and function (Table 1). Specifically, the homebound and semihomebound were older (84.0, 80.6 vs 76.5 years, p<.001), more likely to be female (73.0%, 66.3% vs 53.1%, p<.001), non-white (32.4%, 23.7% vs 16.7% p<.001), and have Medicaid (33.2%, 22.0% vs 8.8%, p<.001) or long-term care insurance (21.0%, 13.9% vs 6.7%, p<.001). They also had more chronic diseases (4.7, 4.1 vs 2.8, p<.001), including higher rates of probable/possible dementia (62.4%, 37.7% vs 14.0%, p<.001) and depression (46.1%, 27.0%, vs 10.1%, p<.001), and were more likely to have been hospitalized in the last 12 months (44.1%, 39.8%, vs 16.8%, p<.001). Lastly, whereas 65.5% of the homebound and 40.2% of the semihomebound were dependent in one or more self-care activity, only 5% of the nonhomebound were dependent to that degree (p<.001). This was also true for dependence in at least one household activity where the prevalence was 78.4% of the homebound, 55% of the semihomebound and 7% of the nonhomebound (p<.001).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Community-dwelling Medicare Beneficiaries by Homebound Status from the National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS), 2011a

| Characteristic | NONHOMEBOUND (n=4762) | SEMIHOMEBOUND (n=1157) | HOMEBOUND (n=481) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p value | p value | ||||

| Age, mean (sd) | 76.5 (7.3) | 80.6 (8.2) | <.001 | 84.0 (8.5) | <.001 |

| Gender, % | <.001 | <.001 | |||

| Male | 46.9 | 33.7 | 27 | ||

| Female | 53.1 | 66.3 | 73 | ||

| Race, % | <.001 | <.001 | |||

| White, non-Hispanic | 83.3 | 75.3 | 67.6 | ||

| Black, non-Hispanic | 7.2 | 10.6 | 12.2 | ||

| Hispanic | 5.4 | 9.7 | 15.3 | ||

| Other | 4.1 | 4.4 | 4.9 | ||

| Education, % | <.001 | <.001 | |||

| <High school | 17.5 | 33.3 | 41.7 | ||

| High school or GED | 26.9 | 27.2 | 28.1 | ||

| >High school | 55.6 | 39.5 | 30.2 | ||

| Living arrangement, % | <.001 | <.001 | |||

| Lives alone | 29 | 35.6 | 39.2 | ||

| Lives with others | 71 | 64.4 | 60.8 | ||

| Helpers, % b | 23.7 | 78.5 | <.001 | 93.5 | <.001 |

| Covered by Medicaid, % | 8.8 | 22 | <.001 | 33.2 | <.001 |

| Long-term care insurance, % | 6.7 | 21.0 | <.001 | 13.9 | <.001 |

| # Chronic Diseases, mean (sd) | 2.8 (1.5) | 4.1 (1.9) | <.001 | 4.7 (2.1) | <.001 |

| Depression (PHQ4) (range 0-6), % | <.001 | <.001 | |||

| 0-2 | 89.9 | 73 | 53.9 | ||

| >=3 | 10.1 | 27 | 46.1 | ||

| Dementia, % | <.001 | <.001 | |||

| Probable/possible dementia | 14 | 37.7 | 62.4 | ||

| No dementia | 86 | 62.3 | 37.6 | ||

| Dependent self-care activities, % c | <.001 | <.001 | |||

| 0 | 95.2 | 59.8 | 34.6 | ||

| 1 - 3 | 4.7 | 29.4 | 42.3 | ||

| 4 - 5 | <1% | 10.8 | 23.2 | ||

| Dependent household activities, % d | <.001 | <.001 | |||

| 0 | 92.7 | 45.1 | 20.6 | ||

| 1 - 3 | 6.6 | 36.6 | 41.7 | ||

| 4 - 5 | <1% | 18.4 | 37.7 | ||

Reference group is the nonhomebound for all comparisons

Has help with self-care activities, household activities, mobility (getting around the house or outside), or medical care-related activities (sitting in with the participant during a medical appointment or help making medical insurance decisions

Self-care activities: eating, bathing, toileting, dressing, transferring

Household activities of daily living: laundry, shopping, preparing hot meals, bills and banking, managing medications

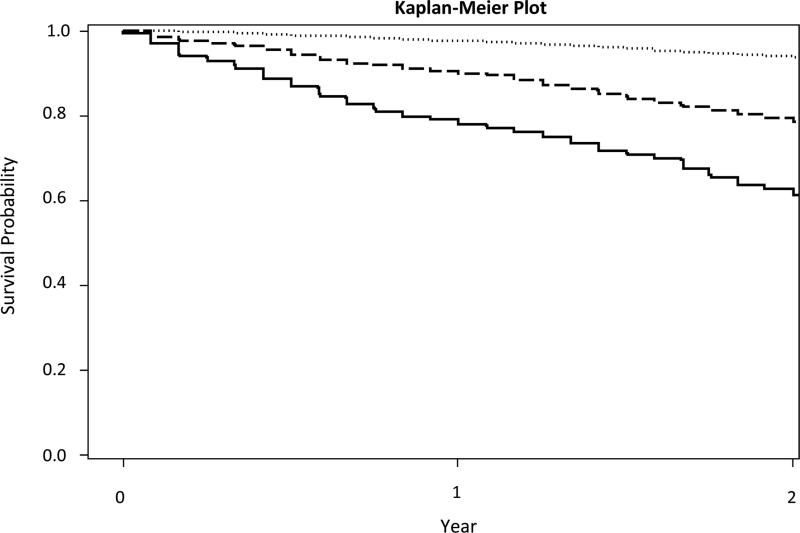

Homebound and semihomebound older adults had higher two-year mortality rates than the nonhomebound (Figure 2). One-year mortality for the homebound was 21% and two-year mortality was 40.3%. In unadjusted analyses, homebound status and semihomebound status were predictive of mortality (hazard ratio [HR] = 8.85; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 7.30-10.73, p<.001 and HR = 4.08; 95% CI 3.29-5.06, p<.001, respectively) (Table 2). After adjusting for demographics (model 2), social support, comorbidities and function (model 3), homebound status remained predictive of mortality in both the homebound (HR = 2.08; 95% CI = 1.63-2.65) and semihomebound (HR = 1.73; 95% CI = 1.33-2.24).

Figure 2.

Two-Year Survival of a Nationally Representative Sample of Community-Dwelling, US Adults over 65 by Homebound Status

Table 2.

| Characteristic | Model 1c | Model 2d | Model 3e | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | |

| Homebound Statusf | ||||||

| Semihomebound | 4.08 | 3.29-5.06 | 3.07 | 2.42-3.88 | 1.73 | 1.33-2.24 |

| Homebound | 8.85 | 7.30-10.73 | 5.18 | 4.14-6.49 | 2.08 | 1.63-2.65 |

Reference group is the nonhomebound for all comparisons.

p <.05 for all comparisons; HR= Hazard Ratio

Model 1= unadjusted;

Model 2= adjusted for age, gender, race/ethnicity, living arrangement, income, long-term care insurance;

Model 3 = adjusted for age, gender, race/ethnicity, living arrangement, income, long-term care insurance, # chronic diseases, depression, dementia, # dependent self-care activities, # dependent household activities.

Reference group is the nonhomebound.

After one year of follow-up, outcomes differed between the homebound, semihomebound and the nonhomebound (Table 3; p<.001 for all comparisons). After two years, a minority (12.1%) of the homebound improved and no longer met the definition of homebound. One quarter (26.9%) was still homebound, 14.9% had difficulty leaving home independently (semihomebound), 5.8% were living in a nursing home and 40.3% were deceased. Of the semihomebound, over one quarter (29.1%) improved and were nonhomebound. Half stayed the same or worsened with 35.9% still semihomebound, 10.2% homebound and 3.6% in a nursing home. The remaining 21.3% were deceased at two years.

Table 3.

Change in Homebound Status over Two Years

| Baseline | 1 year of follow-up | 2 years of follow-up | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonhomebound | Semihomebound | Homebound | Nursing Home | Deceased | Nonhomebound | Semihomebound | Homebound | Nursing Home | Deceased | |

| Nonhomebound, n = 4762 (%) | 87.9 | 7.4 | 2.0 | 0.6 | 2.1 | 82.9 | 8.5 | 2.2 | 0.7 | 5.8 |

| Semihomebound, n=1157(%) | 33.7 | 42.9 | 11.2 | 2.3 | 9.8 | 29.1 | 35.9 | 10.2 | 3.6 | 21.3 |

| Homebound, n=481 (%) | 14.4 | 19.8 | 39.8 | 5.1 | 21.0 | 12.1 | 14.9 | 26.9 | 5.8 | 40.3 |

Almost 700 NHATS participants died within two years of enrolling in the study, representing 2.4 million deaths among community-dwelling, Medicare beneficiaries. Half (50.9%) of all participants were homebound in the year prior to death. Yet, the prevalence of homebound status in the overall population was 5.6%.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that being homebound is an independent risk factor for death among older adults in the United States (hazard ratio, 2.08; 95% confidence interval, 1.63-2.65, p<.001). Specifically, older adults who never or rarely left home had a two-year mortality of 40.3%. Our findings are similar to international estimates of prognosis among homebound older adults,9, 12 as well as estimates of mortality among nursing home residents.31

In this analysis, we conceptualized homebound status as the combination of multi-morbidity, functional impairment and inadequate social support that make it difficult for an individual to leave home and access care. While our data does not allow us to understand the combination of reasons why a given individual does or does not go out, our results suggest that the frequency with which someone leaves home is valuable regardless of the etiology. This is similar to the concept of life-space mobility- a marker for frailty whereby an individual's environment shrinks as their physiologic reserve is overcome by external challenges.32, 33 Decreased life-space mobility is also associated with an increased risk of death.34 Our findings suggest that homebound status may similarly be a marker for frailty and that further research is needed to understand the factors that contribute to homebound status and how it impacts access to care.

Our study also showed that 50.9% of community-dwelling older adults were homebound in the last year of life. This suggests that half of Medicare beneficiaries will have difficulty accessing office-based care when they have the most need. Potential solutions to improve access to care include home-based primary and palliative care and home telehealth interventions. Home-based primary and palliative care (HBPC) is an alternative to office-based care that has been shown to meet patients’ medical needs, including decreasing hospitalizations,35 while simultaneously improving quality of life for patients and their caregivers.36, 37 HBPC also has the added benefit of decreasing overall healthcare costs.38 Similarly, home telehealth interventions have resulted in decreased healthcare utilization among homebound older adults with depression39 and decreased risks of hospitalization and death among patients with congestive heart failure.40, 41 Given that telehealth interventions and HBPC can improve patient and system level outcomes by bringing medical care to the homes of patients with difficulty accessing care, identifying homebound older adults and offering them medical care where they need it will only become more important as our population ages.

This study has limitations worth noting. First, we relied on assessments of patient function that occurred annually and may both under-report the prevalence of homebound status in the last year of life as well as imply more stability in homebound status than actually exists. Monthly assessments of homebound status would allow us to better understand the disabling process and if there is an interaction between the length of time an individual has been homebound and their mortality risk. Second, our model relies on self-reported functional impairment and comorbidities, which may have differing degrees of reliability depending on a participants’ cognitive status and the need for a proxy interview. Finally, our study has a short follow-up time of two years and additional time points are needed to establish the long-term effects of being homebound. Despite these limitations, this paper is the first, to the authors’ knowledge, to describe the impact of homebound status on mortality in a US population. It is strengthened by the use of a large and nationally representative data set, a small loss to follow-up in the sample of 10.5-14.7% per year, and the reliance on a definition of homebound status that is not based on Medicare home healthcare utilization.

CONCLUSION

This is the first study showing an increased risk of death among homebound older adults in comparison to the nonhomebound, adjusted for multi-morbidity and functional impairment. We found that two-year mortality is over 40% among the homebound and that half of community-dwelling, Medicare beneficiaries will be homebound in the last year of life. Multiple effective strategies exist, including home-based primary and palliative care and telehealth, that improve access to care and outcomes for this population. Providers and policymakers need to expand these and other healthcare services to extend primary and specialty from hospitals and clinics to the homes of these frail older adults.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank King Law, MPH, for statistical programming in SAS Software.

Funding Source: The National Health and Aging Trends Study is sponsored by grant NIA U01AG32947 from the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Ornstein was supported by grant K01AG047923 from the National Institute on Aging and by the National Palliative Care Research Center.

| Elements of Financial/Personal Conflicts | *Author 1 Tacara Soones | Author 2 Alex Federman | Author 3 Bruce Leff | Author 4 Albert Siu | Author 5 Katherine Ornstein | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| Employment or Affiliation | x | x | x | x | x | |||||

| Grants/Funds | x | x | x | x | x | |||||

| Honoraria | x | x | x | x | x | |||||

| Speaker Forum | x | x | x | x | x | |||||

| Consultant | x | x | x | x | x | |||||

| Stocks | x | x | x | x | x | |||||

| Royalties | x | x | x | x | x | |||||

| Expert Testimony | x | x | x | x | x | |||||

| Board Member | x | x | x | x | x | |||||

| Patents | x | x | x | x | x | |||||

| Personal Relationship | x | x | x | x | x | |||||

Sponsor's Role: Funding sources had no role in the design, conduct, and analysis of this study or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Author's Contributions: Soones, Tacara: study concept and design, acquisition of subjects and/or data, analysis and interpretation of data, and preparation of manuscript. Federman, Alex: study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, and preparation of manuscript. Leff, Bruce: study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, and preparation of manuscript. Siu, Albert: study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, and preparation of manuscript. Ornstein, Katherine: study concept and design, acquisition of subjects and/or data, analysis and interpretation of data, and preparation of manuscript.

Explanation: Dr. Bruce Leff is on the board of directors of The American Academy of Home Care Medicine and the Voluntary Alliance for Home Health Quality and Innovation. He is also a paid member of the advisory board of Voluntary Landmark Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ornstein KA, Leff B, Covinsky KE, et al. Epidemiology of the homebound population in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:1180–1186. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.1849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Qiu WQ, Dean M, Liu T, et al. Physical and mental health of homebound older adults: an overlooked population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:2423–2428. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03161.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Musich S, Wang SS, Hawkins K, Yeh CS. Homebound older adults: prevalence, characteristics, health care utilization and quality of care. Geriatr Nurs. 2015;36:445–450. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2015.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration Association of cardiometabolic multimorbidity with mortality. JAMA. 2015;314:52–60. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.7008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fried LP, Ferrucci L, Darer J, et al. Untangling the concepts of disability, frailty, and comorbidity: Implications for improved targeting and care. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2004;59:M255–M263. doi: 10.1093/gerona/59.3.m255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fried TR, Bradley EH, O'Leary J. Prognosis communication in serious illness: perceptions of older patients, caregivers, and clinicians. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:1398–1403. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iezzoni L. Risk adjustment for measuring health care outcomes. 3rd edition Health Administration Press; Chicago, IL: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [March 15, 2016];Independence at Home Fact Sheet (online) Available at: https://innovation.cms.gov/Files/fact-sheet/IAH-Fact-Sheet.pdf.

- 9.Cohen-Mansfield J, Shmotkin D, Hazan H. The effect of homebound status on older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:2358–2362. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03172.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mackey DC, Cauley JA, Barrett-Connor E, et al. Life-space mobility and mortality in older men: a prospective cohort study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:1288–1296. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang C, Jackson SS, Bullman TA, Cobbs EL. Impact of a home-based primary care program in an urban veterans affairs medical center. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2009;10:133–137. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herr M, Latouche A, Ankri J. Homebound status increases death risk within two years in the elderly: results from a national longitudinal survey. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2013;56:258–264. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2012.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sarria-Cabrera MA, Gomes-Dellaroza MS, Trelha CS, et al. One-year follow-up of non-institutionalized dependent older adults: mortality, hospitalization, and mobility. Can J Aging. 2012;31:357–361. doi: 10.1017/S0714980812000244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aquaroni-Ricci N, Cereda-Cordeiro R, Dutra-Lemos N, et al. Survival analysis and factors associated with mortality among elderly in a home care program. Home Health Care Manag Pract. 2011;23:102–108. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Freedman VA. Adopting the icf language for studying late-life disability: A field of dreams? J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64:1172–1174. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kasper JD, Freedman VA. National Health and Aging Trends Study user guide: Rounds 1, 2, 3 & 4 Final Release. Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health, 2015 (online).; Baltimore: [May 2, 2016]. Available at: https://www.nhats.org/scripts/documents/NHATS_User_Guide_R1R2R3R4_Final_Release.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Montaquila J, Freedman VA, Edwards B, et al. National Health and Aging Trends round 1 Sample Design and Selection: NHATS Technical Paper #1. Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health; Baltimore: 2012. [May 2, 2016]. (online). Available at: https://www.nhats.org/scripts/sampling/NHATS%20Round%201%20Sample%20Design%2005_10_12.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Administration on Aging and Administration on Community Living [March 15, 2016];A profile of older americans: 2012 (online) Available at: http://www.aoa.gov/Aging_Statistics/Profile/2012/docs/2012profile.pdf.

- 19.Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: Does it matter? J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ganguli M, Fox A, Gilby J, Belle S. Characteristics of rural homebound older adults: a community-based study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:363–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb06403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Freedman VA, Kasper JD, Spillman BC, et al. Behavioral adaptation and late-life disability: a new spectrum for assessing public health impacts. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:e88–94. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The patient health questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care. 2003;41:1284–1292. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, et al. Anxiety disorders in primary care: prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:317–325. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-5-200703060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kasper JD, Freedman VA, Spillman B. Classification of Persons by Dementia Status in the National Health and Aging Trends Study. Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health; Baltimore: 2013. Technical Paper #5. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Galvin JE, Roe CM, Powlishta KK, et al. The AD8: a brief informant interview to detect dementia. Neurology. 2005;65:559–564. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000172958.95282.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Katz S, Downs TD, Cash HR, et al. Progress in development of the index of ADL. Gerontologist. 1970;10:20–30. doi: 10.1093/geront/10.1_part_1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9:179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Montaquila J, Freedman VA, Spillman BC, et al. National Health and Aging Trends Study Development of Round 1 Survey Weights. Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health; Baltimore: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Montaquila J, Freedman VA, Spillman BC, et al. National Health and Aging Trends Study Development of Round 2 Survey Weights. Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health; Baltimore: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Montaquila J, Freedman VA, Spillman BC, et al. National Health and Aging Trends Study Development of Round 3 Survey Weights. Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health; Baltimore: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cohen-Mansfield J, Marx MS, Lipson S, et al. Predictors of mortality in nursing home residents. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999;52:273–280. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00156-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xue Q-L, Fried LP, Glass TA, et al. Life-space constriction, development of frailty, and the competing risk of mortality: The Women's Health and Aging Study I. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167:240–248. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.James BD, Boyle PA, Buchman AS, et al. Life space and risk of Alzheimer disease, mild cognitive impairment, and cognitive decline in old age. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;19:961–969. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e318211c219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boyle PA, Buchman AS, Barnes LL, et al. Association between life space and risk of mortality in advanced age. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:1925–1930. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03058.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Edwards ST, Prentice JC, Simon SR, et al. Home-based primary care and the risk of ambulatory care-sensitive condition hospitalization among older veterans with diabetes mellitus. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:1796–1803. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.4327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ornstein K, Wajnberg A, Kaye-Kauderer H, et al. Reduction in symptoms for homebound patients receiving home-based primary and palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2013;16:1048–1054. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2012.0546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stall N, Nowaczynski M, Sinha SK. Systematic review of outcomes from home-based primary care programs for homebound older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:2243–2251. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.De Jonge KE, Jamshed N, Gilden D. Effects of home-based primary care on medicare costs in high-risk elders. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:1825–1831. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gellis ZD, Kenaley BL, Ten Have T. Integrated telehealth care for chronic illness and depression in geriatric home care patients: The integrated telehealth education and activation of mood (i-team) study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:889–895. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kitsiou S, Pare G, Jaana M. Effects of home telemonitoring interventions on patients with chronic heart failure: an overview of systematic reviews. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17:e63. doi: 10.2196/jmir.4174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kotb A, Cameron C, Hsieh S, Wells G. Comparative effectiveness of different forms of telemedicine for individuals with heart failure: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0118681. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]