Abstract

Births resulting from an unintended pregnancy affect individuals differentially, and some may experience more negative consequences than others. In this study, we sought to describe the mechanisms through which the severity of effects may be mitigated or exacerbated. We conducted in-depth interviews with 35 women and 30 men, all with a youngest child born resulting from an unintended pregnancy, in two urban sites in the United States. Respondents described both negative and positive effects of the child's birth in the areas of school; work and finances; partner relationships; personal health and outlook on life trajectories. Mechanisms through which unintended pregnancies mitigated or exacerbated certain effects fell at the individual (e.g. lifestyle modification), interpersonal (e.g. partner support) and structural (e.g. workplace flexibility) levels. These qualitative findings deepen understanding of the impact of unintended childbearing on the lives of women, men and families.

Keywords: United States, Unintended pregnancy, Childbearing, Parenting, Pregnancy intentions, Qualitative research

1. Introduction

More than one third of all births in the United States are reported as originating from an unintended pregnancy, and this proportion has changed very little over the past 25 years (Mosher et al., 2012; Lindberg and Kost, 2014a). The premise that unintended childbearing has significant negative effects for mothers and children strongly influences public health policy and much of current research on reproductive health and behavior (Institute of Medicine (2011); U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), 2015). Associations between unintended pregnancy and a range of negative outcomes across several domains, including infant health, mothers' socioeconomic and career trajectories and mental health, and parents’ relationship quality, have been documented in the literature (Gipson et al., 2008; Sonfield et al., 2013).

Yet, systematic reviews of published studies have found that the accumulated body of evidence presents mixed findings, with significant variation in the strength of documented associations (Gipson et al., 2008; Logan et al., 2007). Evidence supporting differential outcomes by intention status is often weaker than expected, which may partly be due to broad variation of experiences among individuals who have had an unintended pregnancy – a potentially non-homogeneous classification (Diaz and Fiel, 2016). Limitations of the measure of unintended pregnancy itself may also contribute to diluting the relationship between this driver and any potential consequences (Gipson et al., 2008). In addition, qualitative work has demonstrated that some parents of births resulting from unintended pregnancies report perceived positive impacts of unintended childbearing, such as feelings of improved self-worth and meaning to one's life, as expressed by both women and men living in low-income communities in Philadelphia and Camden (Edin and Kefalas, 2005; Edin and Nelson, 2013), and increased happiness, as described by primarily Latina women living in Austin, Texas (Aiken et al., 2015). This variability in experiences suggests that there may be intervening factors that play a role in determining why some parents of children born as a result of an unintended pregnancy experience more negative or detrimental outcomes, whereas others do not.

Quantitative analyses of population-based data have demonstrated the impact of pregnancy intentions on certain outcomes but do not shed much light on the mechanisms through which these impacts occur. For example, there is evidence that unwanted births are linked to increased relationship dissolution between parents (Maddow-Zimet et al., 2016); yet it is unclear why. A few studies find that stress may contribute to, or exacerbate, the extent to which mothers experience maternal depression as a result of an unintended pregnancy (Horowitz and Goodman, 2004; Nelson & O'Brien, 2012). It is highly likely that there are other mechanisms, beyond those at the psychological level, that help to explain how unintended pregnancies impact people's lives.

To illustrate the role that these mechanisms may play in determining the extent to which individuals experience negative and/or positive outcomes as a result of an unintended pregnancy, we use Lazarus and Folkman's Transactional Model of Stress and Coping (1984). Within this model, stressful events are experienced through a process that is composed of causal antecedents (both individual and environmental factors), mediators and effects (Lazarus, 1991). Building from this model, one's social context influences how he or she experiences the “life event” of a pregnancy, which then triggers an evaluation of the significance of the challenge for his or her own life context (“appraisals”), and ascertainment of the level of control that he or she has and the extent to which “resources” are available to help exert that control. Once these appraisals have been made, the presence (or absence) of coping strategies (strengthened by social support resources) leads to varying effects for the individual. Thus, the processes, or mechanisms, that we seek to describe in this study are measures of individual- and interpersonal-level coping strategies, resources and social support that influence the experience of n pregnancy under the situation in which individuals did not intend for the pregnancy to occur, and can be conceptualized using the Transactional Model. We build on Lazarus and Folkman's model by hypothesizing that mechanisms themselves, in addition to antecedents, may also be structural in nature.

This analysis uses qualitative methods to explore how women and men experience effects of unintended childbearing. We sought to understand the source of variability in the experience of having a child resulting from an unintended pregnancy. That is, our aim is to describe the mechanisms – individual, interpersonal and structural – which may be responsible for variation in the effects individuals experience, and to identify how these mechanisms mitigate or exacerbate those experiences. The focus of this study is not on comparing the perceptions of individuals experiencing an unintended birth to those who have had an intended one, but rather to highlight why the former group's experience of having had an unintended birth results in differential outcomes due to the presence or absence of certain conditions and mechanisms in these individuals' lives. We draw attention to how the unexpected shock of an unintended pregnancy can intensify difficulties already faced by many parents. This study contributes an examination of the mechanisms behind a range of potential effects experienced by both mothers and fathers, and helps us to understand the range of experiences of individuals who raise a child from an unintended pregnancy.

2. Methods

2.1. Sample and data collection

In-depth interviews (IDIs) were conducted with 35 women and 30 men in two urban sites—one in Oklahoma and one in Connecticut—selected for geographic variation to avoid findings which might reflect conditions specific to one location. Demographic characteristics of respondents are presented in Table 1. Respondents were almost evenly split across the two sites and were diverse in terms of age, race and education levels; over half were in the lowest income bracket and most had never been married, subgroups shown to be at high risk of unintended pregnancy (Finer and Zolna, 2016). Notably, our sample included higher proportions of black and Hispanic individuals as well as those living below the poverty line as compared to a comparable national sample of men and women who have experienced unintended birth (unpublished tabulations of the 2006–2010 National Survey of Family Growth).

Table 1.

Number and percentage of respondents by sociodemographic characteristic, according to gender of respondent.

| Characteristic | Total | Female | Male | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Total | 65 | 100 | 35 | 54 | 30 | 46 |

| Age | ||||||

| 25–29 | 27 | 42 | 18 | 51 | 9 | 30 |

| 30–34 | 19 | 29 | 10 | 29 | 9 | 30 |

| 35–39 | 13 | 20 | 4 | 11 | 9 | 30 |

| 40–44 | 6 | 9 | 3 | 9 | 3 | 10 |

| Race | ||||||

| White, Non-Hispanic | 24 | 37 | 13 | 37 | 11 | 37 |

| Black, Non-Hispanic | 28 | 43 | 15 | 43 | 13 | 43 |

| Hispanic | 10 | 15 | 6 | 17 | 4 | 13 |

| Other, Non-Hispanic | 3 | 5 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 7 |

| Union status | ||||||

| Never married | 51 | 79 | 26 | 74 | 25 | 83 |

| Married | 11 | 17 | 7 | 20 | 4 | 13 |

| Divorced or separated | 3 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 3 |

| Poverty statusa | ||||||

| 0–99 | 34 | 52 | 23 | 66 | 11 | 38 |

| 100–199 | 16 | 25 | 8 | 23 | 8 | 28 |

| 200–299 | 10 | 15 | 3 | 9 | 7 | 24 |

| 300+ | 4 | 6 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 10 |

| Education | ||||||

| <High school | 7 | 11 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 17 |

| High school | 21 | 32 | 13 | 37 | 8 | 27 |

| Some college | 28 | 43 | 16 | 46 | 12 | 40 |

| College graduate | 9 | 14 | 4 | 11 | 5 | 17 |

| Interview site | ||||||

| Mid-south, large city | 30 | 46 | 18 | 51 | 12 | 40 |

| Northeast, small city | 35 | 54 | 17 | 49 | 18 | 60 |

Bolded columns represent percentages of the sample, total and by sex, according to each characteristic.

Percent of income relative to federally-designated poverty level for given family size. One male respondent had missing information on this characteristic.

Women and men age 25–44 with a youngest child between 1 and 4 years of age were eligible to participate in the study. We excluded those with children less than one year to focus discussions on longer-term effects rather than on the difficulties of caring for a newborn during a child's first year, and we set the age limit at four to limit potential recall bias. In addition, individuals were asked about the wantedness and timing of the pregnancy leading to their most recent birth during the screening process, employing question wording from the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG). Specifically, individuals were asked “Right before you became pregnant, did you yourself want to have a(nother) baby at any time in the future?” and, if yes, the follow-up question “So would you say you became pregnant too soon, at about the right time, or later than you wanted?” Only respondents who indicated that their most recent child was born as a result of an unintended pregnancy – a “no” response to the first question (unwanted) or a “too soon” response to the second question (mistimed) – were included in the study. Finally, most respondents were not in relationships with any other respondent; we did have two dyads within the sample, but their transcripts were analyzed no differently than the rest of the sample.

Respondents were recruited using both locally-based professional recruiting companies and Craigslist, a popular classified advertisement website. In each location, the recruiting company identified potential respondents who met the screening criteria in its regularly updated database of potential study participants, and supplemented the database with active recruitment and screening of additional potential respondents at the interview location. Respondents from Craigslist were screened for eligibility via phone and email.

Data collection lasted approximately five days in each site and occurred in May and June of 2014. The four-person interview team (authors) conducted the 45–130 min interviews, with most lasting about 90 min. Individual interviews were conducted in private rooms at the recruitment company facility. All participants provided verbal and written consent, and each received $100 cash as compensation. During the informed consent process, respondents were told that they could stop the interview at any time, could decline to answer any interview question, and would still receive full compensation if they chose to do either. At the end of the interview, participants filled out a short questionnaire on sociodemographic characteristics. Study protocols and IDI guides were approved by our organization's federally registered Institutional Review Board.

2.2. Instrument

We developed two IDI guides, one each for men and women. We used Gipson et al.’s review on the potential effects of unintended pregnancy on infant, child and parental health outcomes to guide our study design and identify initial groups of effects to examine (Gipson et al., 2008). We expanded on this work by examining effects beyond the health sphere, including social and economic effects.

The guides were pilot tested with 11 male and nine female respondents in New York City; minor changes were then made to improve the flow and clarity of questions. The interviews, and the guides themselves, were semi-structured. All respondents were asked about the contexts of specific domains in their lives before their (or their partner's) most recent pregnancy occurred and, later in the interview, about these domains after the birth: their relationship with the partner involved in the pregnancy (and other sexual partners around the time of the pregnancy); their financial, employment, schooling and living situations; their free time, daily routines and mental and emotional health. For the purposes of a separate analysis, men were also asked questions regarding their perception and experience of themselves as fathers as well as additional questions regarding their pregnancy intentions. Each of the key areas described above were explored in the interviews, but the semi-structured nature of the guide allowed for flexibility to pursue spontaneous topics that emerged during conversations.

2.3. Data management and analysis

All of the IDIs were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. Identifying information was stripped during the cleaning phase. Initial coding schemes were developed based on the interview guides and existing literature, and were subsequently adapted and updated throughout the coding process. Five members of the research team independently double-coded several transcripts and then met to resolve code differences through discussion and development of new codes. After further double-coding and discussion, all remaining transcripts were coded by at least one member of the research team. We used NVivo 8 to organize the data, code transcripts, and generate reports.

For this analysis, we focused on areas of each individual's life that may have changed following the birth of their most recent child: educational trajectories, work and finances, relationships with partners, physical and mental health and their outlook on the trajectories of their lives. We used Lazarus and Folkman's Transactional Model of Stress and Coping (1984) to guide our thinking about how antecedents, the event of pregnancy, mechanisms and effects were interrelated. To identify the most prevalent effects, we counted first the number of transcripts in which common effects appeared within the aforementioned areas. Effects were further separated into “direction,” where possible, enabling us to look at positive and negative impacts of the birth. Finally, for each effect described by respondents, we revisited the coded text within the narratives describing their experience to identify the pre-pregnancy life circumstances (antecedents) and mechanisms which mitigated or exacerbated the impact of these effects in their lives. Key effects and mechanisms that emerged are summarized via a textured description and illustrated using direct quotes from participants.

To highlight the connection between the circumstances, or antecedents, prior to the pregnancy, including the unintended nature of respondents’ most recent birth, and the life changes that they experienced following it, we include some description of these antecedents in conjunction with quotations illustrating their consequences (these pieces of text did not necessarily occur simultaneously in the interviews). We also examined differences in reported consequences by intention status (mistimed versus unwanted). Respondents are identified using pseudonyms; age and number of biological children for each respondent are provided for context to the accompanying quote.

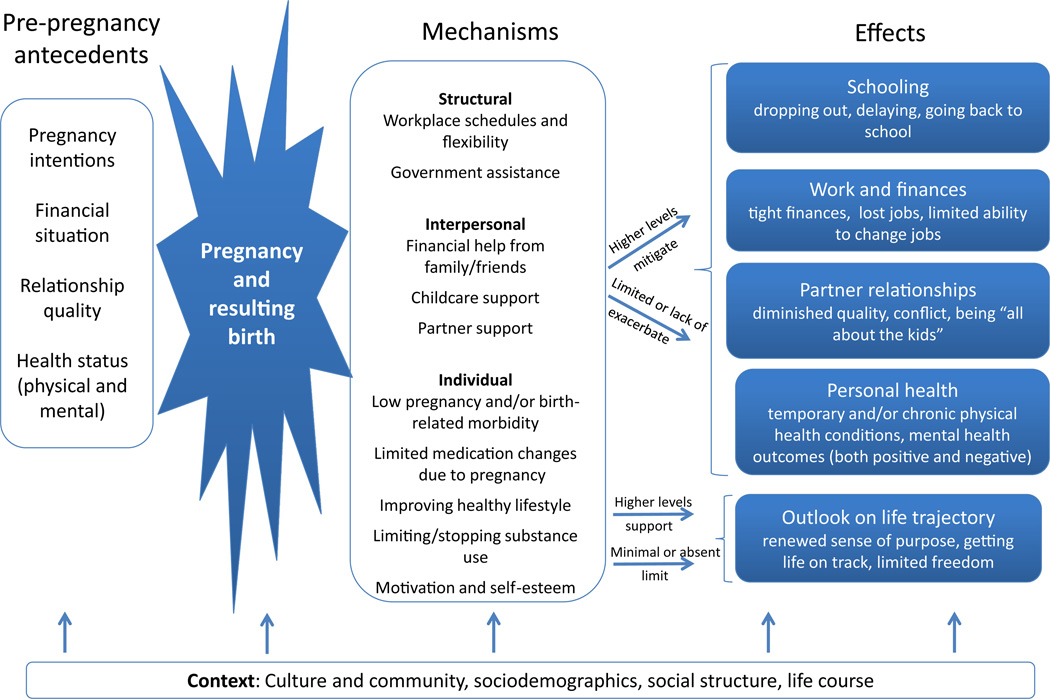

3. Findings

The schematic in Fig. 1 presents areas of effects experienced by respondents whose last birth was the result of an unintended pregnancy, wherein the pregnancy and resulting birth represented a potentially stressful life event preceded by pregnancy intentions characterized as unintended. The figure identifies mechanisms at three levels, which mitigated or exacerbated how respondents' lives were impacted in each of these areas. This figure applies Lazurus and Folkman's Transactional Model of Stress and Coping (1984) to the life event of a pregnancy. Antecedents in place prior to this event (including one's pregnancy intentions, financial situation, relationship quality and health status) can play a role in how, and to what extent, the mechanisms we identified (i.e. Lazarus et al.’s “mediating processes”) impact effects for parents. Mechanisms we identified are conceptualized as occurring at the structural, interpersonal and individual levels.

Fig. 1.

Effects of pregnancy and birth and mechanisms through which a birth may lead to each group of effects.

Below, we present five areas in which our respondents experienced consequences of an unintended birth. Within each area, we first briefly describe the effects experienced and the extent to which our respondents experienced these effects. We then identify both negative and positive effects of these births, although we focus more on the negative effects for most areas because they were more common than positive ones. Within each area, we present findings on the pre-pregnancy antecedents in respondents' lives, as well as the mechanisms through which they experienced the impacts of the birth. We end with a summary of the differences in consequences identified among respondents by screener intention status of the pregnancy leading to the youngest child's birth. Importantly, although a key inclusion criterion for this study was the unintended nature of respondents' (or their partners') most recent birth, effects identified below are not necessarily unique to births resulting from unintended pregnancies.

3.1. Schooling

Educational trajectories are often interrupted or altered by a pregnancy or birth of a child. While education came up rarely in the narratives of the men we interviewed, interruptions in schooling were common in women's stories. More than half of female respondents were enrolled in school either during pregnancy or soon after the birth; of these, just over half dropped out during the pregnancy or following the birth. Only two women had returned to school by the time of the interview.

Of the women who dropped out of school, half identified physical issues related to pregnancy (nausea, fatigue or a high-risk pregnancy) as the main reason for interruption. Pregnancy took a considerable toll on the educational trajectory of the following woman, who felt stressed and depressed during the pregnancy and wanted another child “in the future … but not right [then]:”

My ankles started swelling real bad … And I couldn't keep no food down, nothing like that …And not having energy…they put me on bed rest for a few months … I took a leave at school actually. Six months of leave, but—and I was going to go back, but I never went back. (Jeanine, 30 years old, 2 children)

After the birth, lack of childcare support became a significant obstacle for many women; even among those who were not in school during the pregnancy or after the birth, several spoke of delaying school because of difficulty finding childcare while they attended classes. Of the women in school either during or following the pregnancy, one quarter dropped out because of childcare difficulties or the need to work to support their child. One woman, who had a volatile relationship with her partner and lived alone with her children, said she “did not want” the pregnancy, and articulated the challenge of returning to school:

I want to go to school right now. I live right down the street from [the community college]. My problem is that I don't have enough help with my kids, it's just me – there's no free time for me. Every time you see me you see my kids. I have them with me 24/7 and I don't complain because that's my job, but that's where it gets hard for me … my mom and dad they're both sick now, [and] my brother he's working now (Erika, 27 years old, 4 children)

In contrast, for a small number of women, an unintended pregnancy became a catalyst motivating them to pursue school to help secure a better job to support their family or to be a role model to their children. All of these women had a partner or other family member to help with childcare, enabling them to fit schooling into their lives.

3.2. Work and finances

Adding a(nother) child to the household also presented financial challenges for many respondents. Most of the mothers and about half of the fathers reported having less money and struggling more financially post-birth as compared to their pre-pregnancy financial situations. Two-thirds of mothers and about half of fathers reported negative impacts on their working situation either during the pregnancy or after the birth. For several respondents, the child motivated moving to a different or larger home, which brought with it additional expenses. Financial struggles were common and translation of these hardships into anxiety and stress over support for one's family was nearly ubiquitous among respondents.

Most respondents were working for pay at the time the pregnancy occurred, though some were doing so sporadically and/or outside of the formal labor system (e.g. short-term jobs or childcare). Less than a quarter of respondents described having jobs with flexibility or ability to set their own schedules, before the pregnancy. Lack of childcare support was again a large factor in both interruptions in work and financial difficulties. Both women and men talked about difficulties finding or maintaining work because of childcare issues, though men more commonly talked about having limited freedom to look for side work than they did about dropping out of the work force all together. For example, one male respondent who had been working full time and doing well financially before the birth and was “thinking of having a kid but not for at least a few years down the line” talked about an inability to further improve his financial situation because of the difficulty finding work that aligned with his available childcare:

It's like I feel like I can't even proceed in getting a better job because just the way the hours are, it works with the [childcare] scheduling you know what I mean? So it's like I feel like I'm stuck unless I could find another job that's 9:00 to 5:00 you know what I mean and more money. (Jared, 32 years old, 1 child)

In contrast, support from extended family or others were often mentioned as mitigating financial impacts of the birth. Both childcare and financial support from family members were common, as well as support from government programs such as WIC, unemployment and subsidized housing. Carla, who had lost her job and was struggling financially, and didn't think she was “ready at that point” for a pregnancy, described relying on both government aid and her mother to help with finances after the birth:

[at first I] thought … ‘oh my God we're really gonna be broke,’ but luckily my mother stepped up like, no tomorrow. WIC is amazing, so they - they were a huge help, actually. You know we get food stamps, still, so we're able to nutritionally provide for him. And mother brings the diapers and the wipes every week. So I mean he's taken care of. (Carla, 32 years old, 1 child)

A third of female respondents indicated that they didn't experience any impacts or changes in their work situations from before to after the birth; for these women, family support, particularly with childcare, was often a key factor. Amber, who “really wasn't going for getting pregnant,” described how her mother's daily support allowed her to maintain her work schedule following the birth:

We all get up at about 6:45 and then my mother comes over for my 4-year-old and she'll take care of him while I'm at work and my other son goes to school and then she'll pick him up and then we'll all meet back at home at about 4:00 to 4:15 … I love that because I know that they are safe and I can go to work and get out…[and] be at home with my kids. (Amber, 36 years old, 2 children)

Other common factors among this group included characteristics of their workplace, specifically flexibility in scheduling or ability to work from home and availability of maternity leave.

About a quarter of respondents experienced improvements in their finances since the birth. For men, this was achieved through increased motivation to work more or to get higher paying jobs; for women, this was also the case, but many also pointed to their partner moving in or helping with finances. Both men and women described becoming more financially savvy and responsible.

3.3. Partner relationships

Many respondents encountered challenges in their relationship with the other parent of the child. Friction between parents — among both those that maintained and ended their partnerships — was common, although many also articulated how their relationships had improved following the birth.

More than half of respondents mentioned a diminished quality of the relationship. This included more fighting, poorer communication, increased stress, introduction of mistrust and resentment, less attention from or to the partner, less closeness, and a poorer sex life. Many respondents — more often women than men — described a lack of partner support, including having little to no help in child care and (perceived) minimal partner interest in raising the child as factors that contributed to weakening of the relationship. The following quote from Jeanine, whose relationship with the child's father was on and off prior to the pregnancy, captures a sentiment shared by almost half of the women:

He didn't do anything. It was more like me raising my child, with [my partner] there […] you need two people to raise a baby because if you don't it gets really, really hard. (Jeanine, 30 years old, 2 children)

The demands of childcare and financial support were also mentioned as factors which put a strain on couples, often because there was not enough time remaining for the relationship. This was the case for Gerald, who said his pre-pregnancy relationship was fun and enjoyable but the pregnancy “was just unplanned”:

If I worked an overnight shift, she would work first shift so I am overnight, she is sleeping; she is working and I am sleeping. She gets out, I am up. We tried to make it to where we could have time but it always turned out to be like only a sliver of time. We just fell apart trying to hold everything together. (Gerald, 25 years old, 1 child)

Several respondents described relationships held together only by responsibility for the child[ren]. And, being “all about the kids” with nothing left for the relationship often resulted in couples staying together solely for the child[ren]. Jessica, who “definitely wasn't ready [to get pregnant] at that point in time,” had just happily moved in with her partner when the pregnancy occurred. After the birth, however, she described her frustration with how their relationship changed:

Basically, we just co-parent. We don't really — I don't know, we have been together on and off since we were 15. We don't really have this great relationship. Just do the best for our kids. It's our main focus, is making sure they have what they need. (Jessica, 30 years old, 2 children)

Finally, the context and quality of the parents' relationship prior to the pregnancy played a substantial role in how, and to what extent, the unintended birth negatively impacted the relationship. The demands of parenting were exacerbated by poor quality or strained relationships before the pregnancy. In fact, respondents who reported that they had hoped the birth of the child would “fix” the relationship more often than not found that it did not, including Julio, who “didn't want any more kids”:

I figured that at that time it might fix some of the things that were going on. I figured this was a new start, this is a new beginning. This was a new child, you know, we can come together and raise this child together, and coming up we can do these things together, you know. I figured it would fix things. It didn't. (Julio, 35 years old, 2 children)

In contrast, respondents who reported having relatively stable and happy relationships prior to conception of the unintended pregnancy were more likely to report positive effects of the birth for the relationship with their partner.

3.4. Personal health

Nearly half of respondents described an impact of the pregnancy and/or birth on their physical health, and the vast majority reported experiencing an impact on their mental health (whether positive or negative).

Women were much more likely than men to experience effects on their physical health; they described both temporary health conditions arising during pregnancy and having preexisting conditions exacerbated by the pregnancy. Several women experienced a worsening of preexisting health conditions because they had to stop taking medications during the pregnancy. Tricia, who, “wasn't even thinking about [becoming pregnant]” had epilepsy; the frequency of seizures increased after stopping medication:

When I was pregnant with [my youngest child], it was maybe a month into my pregnancy…. I ended up going into an epileptic seizure … I did go into - start getting seizures again since not being on the medication … But I know when I got the medicine, I wasn't getting them. But now I'm having the baby, they took me off. A month later, I started getting them again, and I still get them now. (Tricia, 28 years old, 2 children)

Tricia is one of several women whose health conditions arose or worsened during pregnancy, and continued after giving birth. These women described high blood pressure, strokes, diabetes, anemia, excessive weight gain, and one case of cardiomyopathy, leading to congestive heart failure.

Respondents also reported negative mental health effects of the birth, including feeling overwhelmed by parenting responsibilities, stressed by financial issues, angry and depressed; these emotional tolls were common among both male and female respondents. More women than men reported severe mental health impacts, including diagnosed conditions, postpartum depression, suicide attempts, or hospitalization due to a diagnosed disorder.

Some women, such as Amy, had preexisting mental health conditions that were exacerbated by the pregnancy:

I was kind of like just stressed out, just devastated that I was pregnant because I didn't want another baby … I actually broke down and had depression issues and had to be admitted to a- like a crisis center or something, and I was there for like seven days…I've always been depressed as a kid but I just never did show but like when I got pregnant with E. and just felt like nobody, like her father wasn't there for the appointments or anything like that … so I just got- I just- lost it. … It's was just so many things going on in my mind with the pregnancy and also what am I going to do and it's just too much. (Amy, 28 years old, 4 children)

As in the case of physical disorders, the need to discontinue medication during pregnancy also contributed to worsening of preexisting mental health conditions. Laura, who “didn't know 100% that [she] necessarily wanted another child,” described the consequences of discontinuing medication:

R: Well, I have bipolar and anxiety disorder, so I take medication for that and if I miss my medicine then I can get pretty depressed. […]

I: Tell me about during the pregnancy, did you have to go off it?

R: I had to. And it — it was difficult, um, I would spend like days in bed and just wouldn't want to do anything, but that's just something that came along with it, and I had to deal with that. (Laura, 30 years old, 2 children)

Despite describing significant negative mental health impacts of the most recent birth, the majority of respondents also reported positive impacts, including improved emotional outlook and feeling increased confidence. Respondents spoke about the joy their children had brought, the day-to-day pleasure of being with them and feeling that their lives were fuller and more meaningful.

Among both men and women, those that described a lack of support from a partner or others following the birth tended to experience more negative mental health effects. Having a supportive partner or network, on the other hand, acted as a buffering mechanism to mitigate the negative effects of the birth, especially among those respondents with sub-optimal mental health before the pregnancy.

3.5. Outlook on life trajectory

In talking about the above areas of their lives that were affected by the pregnancy and birth of their most recent child, respondents often spoke spontaneously about changes related to their life and its trajectory. Within this domain, they more frequently described positive effects, such as feeling a renewed purpose and getting one's life on track, than negative ones. Modifying one's lifestyle, especially “settling down,”was described as a mechanism by which several respondents achieved these positive changes. Chris, who “didn't want any more kids and didn't want that burden” described how his son prompted change:

My son is a blessing to me, he put my life on track, you know, and I'm glad. I just wanted to go out and have fun. That was my thing, and he … I'll trade fun for spending time with him any day. (Chris, 33 years old, 2 children)

Explicit substance use factored into the stories of about a third of respondents, and becoming motivated to limit or stop use was often described as a mechanism affecting a positive change. Of these respondents, a decrease in the level of substance use during pregnancy, or a complete discontinuation altogether, was commonly mentioned.

Positive effects within this domain were more commonly cited by men than by women; women reported a broader array of negative life-trajectory-related consequences than did men. Both men and women reported feeling they had no freedom or ability to be spontaneous, while women described frustration at having to rely on others for help and sacrificing her happiness for her child(ren)’s. A lack of support, especially in terms of childcare, exacerbated respondents’ sense of “feeling trapped” and isolation:

People are very helpful when you're pregnant and see that's, that's the negative thing about being pregnant because everybody acts like they're there to help you while you're pregnant but then when you have your baby, there's no one there. You find yourself by yourself … So I'm leaving work. Oh, I got him. There's no way I can go have drinks or, you know, or go to the mall, come here. (Jana, 30 years old, 2 children)

3.6. Differences in experience of consequences by intention status

Unwanted childbearing had somewhat more negative impacts – and fewer positive ones – than mistimed childbearing on most of the domains we examined. For example, both women and men with births resulting from unwanted pregnancies more often mentioned lack of partner support and more negative life trajectory-related consequences than did respondents with births characterized as mistimed. Respondents' mental health following the recent birth was less frequently cast in a positive light among those whose births were unwanted. In contrast, both men and women with mistimed births more commonly described positive impacts on their financial situation than did those with unwanted births. Increased relationship stability and appreciation of one's partner were also more often noted among women whose recent birth was mistimed.

In part, these differentials may be impacted by the context of respondents' lives, which themselves influence whether a respondent classifies a pregnancy as mistimed or unwanted. The following respondents' narratives illustrate the differences in the trajectory experienced – from antecedents through mechanisms and resulting in effects – between a birth resulting from an unwanted pregnancy and one resulting from a mistimed pregnancy. In the first quote, prior to the most recent pregnancy, Erika, a single mother, was having difficulty financially supporting two children, had experienced health troubles with her previous pregnancies, and had not wanted to become pregnant. With the addition of another child, she continued to struggle financially because the relationship with her partner didn't work out and her high-risk pregnancy limited her ability to work, all effects that were exacerbated by a lack of financial and childcare support:

[My child]’s pregnancy was high risk, so I had to quit working since the first trimester. I was by myself …And then me and [my partner] obviously – didn't work at all. So I had to leave. I mean there was days when me and girls didn't eat. I mean, I lost like 27 pounds during my pregnancy, so it was kind of tough.

[…] I don't have enough to offer [my kids]. Sometimes I struggle even the – I have to take my food out my mouth to help them out, you know. (Erika, unwanted birth, 27 years old, 3 children)

Erika stands in stark contrast to Laura who had a relatively stable and long-term relationship with her partner, as well as some financial security, prior to the most recent birth; as such, she hadn't thought much about either planning or preventing pregnancy. This mother also had difficulties with pregnancy that impacted her ability to work, but the presence of her partner mitigated the extent to which she felt financially stretched:

R: I just was gone all the time from work, and I was sick – so I was like, I'm just going to take a leave of absence and wait until I have this baby.

I: How did that work out financially?

R: Well [my partner] was making twenty five dollars an hour at that time so it wasn't really that big. My check was, like, spending money; like, go to the movies or go to the water park. We had to cut back on going out to eat and stuff like that but other than that it wasn't that big of a financial difference. (Laura, mistimed birth, 30 years old, 2 children)

4. Discussion

Births from unintended pregnancies present a wide array of effects that are moderated by mechanisms that occur at the structural, interpersonal and individual levels within parents’ lives. Many of the consequences of unintended childbearing identified by these respondents are not unlike those experienced by all parents, regardless of pregnancy intentions, such as having to quit work because of a high-risk pregnancy or feeling stressed over family responsibilities. However, challenges encountered by all parents may be exacerbated for those who did not plan or did not want to have a child, such as the respondents in this study.

As theorized by Lazarus and Folkman, the stress of experiencing a major life event – a pregnancy – can be heightened by the presence or absence of both pre-pregnancy antecedents as well as post-birth mechanisms through which the effect of the pregnancy on individuals' lives is mediated. The presence (or lack of) stability in one's finances, relationships and health pre-pregnancy influences whether a pregnancy is perceived and reported as “unintended,” and these antecedents shape both the effects the respondent experiences as well as what mediating mechanisms are available to them. For example, the degree to which an individual experiences relationship strain after a birth is affected by relationship quality pre-birth. At the same time, lack of partner support with both childcare and finances can derail a mother's planned educational trajectory and overwhelm the family budget. Conversely, the presence of partner support with shared childcare and co-parenting can both enable a mother to return to work, strengthen a couple's bond and motivate positive lifestyle changes. These types of simultaneous and reciprocal impacts across the process were evident across most of the domains of effects identified.

We found effects in both directions (and at many places in between) on the negative to positive spectrum. Yet, positive effects are to be expected — having a child can feel like a miraculous experience, bringing unanticipated joy and meaning to one's life. Indeed, research has shown that women and men experiencing unintended childbearing often express happiness about the birth, and some find meaning and motivation in their lives as a result (Hartnet, 2012; Lindberg and Kost, 2014a; Lindberg et al., 2016; Aiken et al., 2015). Recognizing that positive effects of unintended childbearing exist alongside negative ones could help to refine the messages of future campaigns aimed at reducing unintended pregnancy as well as situating motherhood and/or fatherhood resulting from unintended pregnancy as an opportune time to engage parents in educational or work programs that support positive outcomes. Indeed, this study suggests that the presence of certain resources, such as flexibility in the workplace and a supportive network of childcare, may be key mechanisms leading to an increased likelihood of positive experiences.

Of greatest concern, however, are the negative impacts of unintended childbearing, reported by almost all respondents, frequently relatively serious and difficult ones. A few respondents had not been able to complete school or had to leave jobs with potential for advancement and were not able to recoup lost opportunities because of the demands of childcare. We found that structural mechanisms, in addition to the individual- and interpersonal-level ones described in Lazarus and Folkman's (1984) model greatly influenced how mothers and fathers experienced unintended childbearing and their ability to cope successfully with the challenges of parenting. When certain structural and interpersonal factors, such as workplace flexibility and financial and childcare support, were absent or limited, the birth impacted respondents' lives to a more negative degree. Although not all negative effects identified in this study are avoidable, efforts to increase the availability of these and other structural and interpersonal resources identified in this study will likely contribute to mitigating the negative impact of an unintended pregnancy on parents' lives.

Although comparison of mothers and fathers experiences was not a primary focus of this analysis, women tended to report negative consequences to a greater degree than did men, especially in terms of having schooling plans derailed, and in experiencing both negative physical and mental health consequences, as well as a broader array of negative ramifications for their life trajectories. For men, difficulties in their relationships from the added stress of the child or the lack of a positive relationship with the mother meant they spent far less time with their children than they wanted to, often expressing fear that the child would suffer because of it. For both men and women, relationship struggles that both contributed to, and were exacerbated by, the unintended pregnancy can translate into a lack of partner support and place a greater share of the parenting and childcare burden on one parent. This study is among the first to highlight consequences experienced by men (Lindberg et al., 2016; Bronte-Tinkew et al., 2007; Bronte-Tinkew et al., 2009; Edin and Nelson, 2013). Future research to delve further into how men and women differentially experience and manage unintended childbearing is warranted.

We found some evidence of a difference in the level of impact experienced by individuals who had had a birth resulting from an unwanted pregnancy compared to those who had a mistimed one. Since births resulting from mistimed and unwanted pregnancies are more common among more economically disadvantaged individuals such as the ones in our study (Finer and Zolna, 2016), our findings may reflect the difficulty of separating out the effects of background characteristics (antecedents) on the experiences of having a child from an unintended pregnancy from the impact of the event itself.

Revealing effects of unintended childbearing as experienced and described by both mothers and fathers is a key strength of this study. In addition, these qualitative data provide insight into the pathways that exist between variables modeled with unidirectional relationships in quantitative analyses. However, our findings cannot be generalized to the broader population of individuals experiencing unintended childbearing, despite the disproportionate number of poor men and women in our sample, subgroups who are more likely than their wealthier counterparts to experience unintended childbearing (Finer and Zolna, 2016). Variation in local and state programs and policies that either hinder or support individuals in preventing unintended pregnancy or raising children with limited resources would likely impact the extent to which individuals in other settings might experience many of the consequences we found. In addition, given the widely documented limitations regarding the measurement of unintended pregnancy (Luker, 1999; Klerman, 2000; Santelli et al., 2003), it may be that variation in consequences documented in the literature among those experiencing unintended pregnancy is at least partly due to measurement limitations. Thus, our choice to exclude individuals reporting a youngest child resulting from an intended pregnancy could have excluded parents whose experience of effects, and of the mechanisms that may have mitigated these effects, were similar to our sample of parents experiencing unintended births. Retrospective reporting bias may have also played a role, such that some parents recall the pregnancy intention differently than how they had actually felt prior to becoming pregnant. Of more concern would be bias related to recalling negative experiences, if parents tend to remember these more positively as the infant ages. In this study, however, this would mean parents underreported the severity of negative consequences.

We set out to illuminate processes by which individuals are able to differentially handle the impact of an unintended pregnancy that are not currently measured in quantitative analyses, with the aim of revealing aspects of people's lives that should be addressed in future efforts to alleviate the burdens of unintended childbearing. Our findings point to consequences that have been difficult to document in survey research, but ones which were very real to our respondents, such as the impact of a birth on an individual's educational and occupational aspirations; in short, plans put on hold or derailed altogether.

In addition, we have shown how parents of children resulting from unintended pregnancies experienced both negative and positive effects resulting from the birth, sometimes within the same life domains concurrently. A woman could describe the increased motivation and confidence she felt as a mother while simultaneously expressing overwhelming stress about supporting her family since her most recent birth. The absence or presence of mechanisms at the structural, interpersonal and individual levels often moderated the extent to which parents perceived the negative impacts of the birth of their most recent child.

Acknowledging the complexity and breadth of an individual's experience of unintended childbearing is an important first step towards improving future work in this area. These findings advance our understanding of the effects of unintended childbearing and the mechanisms through which these pregnancies can, and the extent to which they do, influence the experience of consequences. The processes described in this paper shed light not just on the experience of unintended childbearing, but on the challenges of parenting and the need for social services and support in these contexts. Additional qualitative research could help to unpack how these mechanisms and their consequences differ between fathers and mothers, or first versus subsequent births, as well as provide greater context for the relationship between pregnancy decision-making (consideration of abortion or adoption along with parenting) and post-birth consequences. Developing new survey questions to capture mechanisms and effects described in these respondents' stories will advance measurement of the variation in experiences of unintended childbearing in future fertility surveys. Ultimately, program planners and policy makers may be able to target adverse outcomes of unintended childbearing and the conditions of people's lives in which they occur in order to improve the health and well-being of parents and their families.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Lawrence Finer and Laura Lindberg for their reviews of the paper and Marjorie Crowell, Joon Lee and Jessie Philbin for their research assistance. Work for this study was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01HD068433. Additional support was provided by the Guttmacher Center for Population Research Innovation and Dissemination (NIH grant 5 R24 HD074034). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Aiken AR, Dillaway C, Mevs-Korff N. A blessing I can't afford: factors underlying the paradox of happiness about unintended pregnancy. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015;132:149–155. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.03.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronte-Tinkew J, Ryan S, Carrano J, Moore KA. Resident fathers' pregnancy intentions, prenatal behaviors, and links to involvement with infants. J. Marriage Fam. 2007;69(4):977–990. [Google Scholar]

- Bronte-Tinkew J, Scott ME, Horowitz A. Male pregnancy intendedness and children's mental proficiency and attachment security during toddlerhood. J. Marriage Fam. 2009;71(4):1001–1025. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz CJ, Fiel JE. The Effect (s) of teen pregnancy: reconciling theory, methods, and findings. Demography. 2016;53(1):85–116. doi: 10.1007/s13524-015-0446-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edin K, Kefalas M. Promises I Can Keep: Why Poor Women Put Motherhood before Marriage. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Edin K, Nelson TJ. Doing the Best I Can: Fatherhood in the Inner City. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Finer LB, Zolna MR. Declines in unintended pregnancy in the United States, 2008–2011, 2016. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016;374:843–852. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1506575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gipson JD, Koenig MA, Hindin MJ. The effects of unintended pregnancy on infant, child, and parental health: a review of the literature. Stud. Fam. Plan. 2008;39(1):18–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2008.00148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartnet C. Are Hispanic women happier about unintended births? Popul. Res. Policy Rev. 2012;31(5):683–701. doi: 10.1007/s11113-012-9252-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz JA, Goodman J. A longitudinal study of maternal postpartum depression symptoms. Res. Theory Nurs. Pract. 2004;18:149–163. doi: 10.1891/rtnp.18.2.149.61285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Clinical Preventive Services for Women: Closing the Gaps. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Klerman LV. The intendedness of pregnancy: a concept in transition. Maternal Child Health J. 2000;4(3):155–162. doi: 10.1023/a:1009534612388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus R, Folkman S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS. Emotion and Adaptation. London: Oxford University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg LD, Kost K. Exploring U.S. men's birth intentions. Maternal Child Health J. 2014;18(3):625–633. doi: 10.1007/s10995-013-1286-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg LD, Kost K, Maddow-Zimet I. The role of men's childbearing intentions in father involvement. J. Marriage Fam. 2016 doi: 10.1111/jomf.12377. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan C, Holcombe E, Manlove J, Ryan S. The Consequences of Unintended Childbearing. Washington, DC: Child Trends and National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Luker K. A reminder that human behavior frequently refuses to conform to models created by researchers. Fam. Plan. Perspect. 1999;31(5):248–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddow-Zimet I, Lindberg LD, Kost K, Lincoln A. Are pregnancy intentions associated with transitions into and out of marriage? Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2016;48(1):35–43. doi: 10.1363/48e8116. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosher WD, Jones J, Abma JC. Intended and unintended births in the United States, 1982–2010. Natl. Health Stat. Rep. 2012;55:1–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson JA, O'Brien M. Does an unplanned pregnancy have longterm complications for mother-child relationships? J. Fam. Issues. 2012;33(4):506–526. doi: 10.1177/0192513X11420820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santelli J, Rochat R, Hatfield-Timajchy K, Gilbert BC, Curtis K, Cabral R, Hirsch JS, Schieve L. The measurement and meaning of unintended pregnancy. Perspect. Sex. Reproductive Health. 2003;35(2):94–101. doi: 10.1363/3509403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonfield A, Hasstedt K, Kavanaugh ML, Anderson R. The Social and Economic Benefits of Women's Ability to Determine whether and when to Have Children. New York: Guttmacher Institute; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) Healthy People 2020 Topics and Objectives. 2015 Retrieved from. http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/default.