Abstract

Background

Observational studies suggest an inequitable prescription of biologics in psoriasis care, which may be attributed to geographical differences in treatment access. Sweden regularly ranks high in international comparisons of equitable healthcare, and is, in connection with established national registries, an ideal country to investigate potential inequitable access.

Objective

The aim was to determine whether the opportunity for patients to receive biologics depends on where they receive care.

Methods

Biologic-naïve patients enrolled in the Swedish National Register for Systemic Treatment of Psoriasis (PsoReg) from 2008 to 2015 (n = 4168) were included. The association between the likelihood of initiating a biologic and the region where patients received care was analyzed. The strength of the association was adjusted for patient and clinical characteristics, as well as disease severity using logistic regression analysis. The proportion of patients that switched to a biologic (switch rate) and the probability of switch to a biologic was calculated in 2-year periods.

Results

The national switch rate increased marginally over time from 9.7 to 11.0%, though the uptake varied across regions. Adjusted odds ratios for at least one region were significantly different from the reference region in every 2-year period. During the latest period (2014–2015), the average patient in the lowest prescribing region was nearly 2.5 times less likely to switch as a similar patient in the highest prescribing region.

Conclusions

Geographical differences in biologics prescription persist after adjusting for patient characteristics and disease severity. The Swedish example calls for further improvements in delivering equitable psoriasis care.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s40259-016-0209-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Key Points

| While the Swedish healthcare system has established measures against inequitable treatment access, geographical differences in the prescription of biologics were present after adjusting for patient characteristics and disease severity. |

| Over time, regional differences did not disappear, nor decrease in magnitude, though the national switch rate to biologics was stable at approximately 10%. |

| Evidence of persistent regional differences in access to biologics motivates similar investigations in other countries. |

Introduction

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory skin disease with a prevalence rate in adults of 1–5% in the Nordic region [1–4]. The incidence of psoriasis in Swedish specialist care between 2007 and 2009 has been estimated at 98 per 100,000 person-years [5]. Patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis typically require systemic treatments, which include conventional systemic agents, small molecule inhibitors, biological agents (adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, ixekizumab, secukinumab, and ustekinumab), and now even emerging as biosimilars (etanercept and infliximab). In Sweden, biologics were first available for psoriasis care in 2004. According to Swedish national guidelines, biologics are indicated for adult patients with psoriasis who do not respond to, are intolerant of, or have a contraindication for conventional systemic treatment. Before initiating biologics treatment, the condition of having disease severity scores indicating moderate-to-severe psoriasis should be fulfilled and consideration should be given to the location of skin lesions and the presence of psoriatic arthritis (PsA) [6].

In previous observational studies, some patients with severe forms of psoriasis were not prescribed biologics, while others who did not fulfill the criteria for moderate-to-severe psoriasis received prescription [7, 8]. Aside from disease severity, a number of factors have been reported to affect the prescription of biologics. Elderly patients were observed to be significantly less likely to initiate the treatment [9]. Males were also observed to be more likely to be prescribed, though the disparity was attributed to greater disease severity in males than females [10]. Small or no difference in prescription was found between types of healthcare provider [11]. Geographical factors may play a role as sales of biologics varied internationally in the first year of use [12]. Within Sweden, sales of biologics per capita were observed to vary considerably between different geographical entities [13, 14].

Geographical variations in healthcare delivery become a concerning issue to patients, to payers, and to the medical community when they cannot be associated with differences in patient clinical characteristics and disease severity [15, 16]. At first glance, potential geographical variations in Sweden may be overlooked. Sweden often ranks high when compared to other high-income countries with respect to providing effective and equitable healthcare [17–21], and goals of equitable healthcare access have been a governing provision of care for decades in Sweden [22]. Furthermore, prescription medications are free of charge to patients after accumulating 2200 Swedish Krona (SEK) [€235; €1 = 9.35 SEK (2016)] in expenses annually and expenses for medical visits after SEK 1100 (€118) through tax-financed health insurance covering all citizens, reducing financial barriers for patients. International rankings and government initiatives nevertheless typically rely on readily available general measures relating to overall healthcare use. Such measures may fail to reveal variations in subgroups with more well-defined needs. As previous studies highlight, a pertinent case to investigate is access to biologics treatment in psoriasis care. By using established national registries, Sweden is an ideal country to investigate potential inequitable access to biologics treatment based on regional prescription differences.

The objective of the analyses was to determine whether the opportunity to receive biologics treatment depends on where one receives care geographically. To do so, we investigated potential regional differences in biologics prescription over time in Sweden by estimating the likelihood of switch to a biologic by region.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

The Swedish National Register for Systemic Treatment of Psoriasis (PsoReg) was established in 2006 to assess the long-term safety and effectiveness of systemic psoriasis treatments in Sweden [23, 24]. PsoReg is a national register comprising 57 participating dermatology clinics and departments in hospitals located across Sweden. Health providers participate voluntarily and enroll people diagnosed with psoriasis who are using, or are about to start, systemic treatment. There has been no change in the inclusion criteria of the register over time. The study period was from January 2008 to December 2015.

Study Design

Included patients were all patients with no prior use of biologics (biologic-naïve) and could at any time in PsoReg be switched to biologics or remain on conventional treatment throughout the full study period. A switch was defined as a first-time prescription of biologics either as an addition to, or as a replacement of, ongoing conventional systemics. The study defined treatment with biologics as any of the biological agents approved for psoriasis in Sweden during the time of the analysis (adalimumab, etanercept, efalizumab, infliximab, secukinumab, and ustekinumab). Efalizumab was withdrawn by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in 2009 due to serious side effects.

To explore time trends, PsoReg data were analyzed in 2-year periods (2008–2009, 2010–2011, 2012–2013, and 2014–2015). Cross-sectional datasets for each period comprised biologic-naïve patients who had an observation during that time. One observation was included per patient; for patients who never switched to biologics (non-switchers), the last available observation in each 2-year period was used, while for each patient who switched (switchers), the last observation before switch was used. Switchers in the dataset should have had at least one observation before switch. For both switchers and non-switchers, a registration of disease severity measured by the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) was required.

Variables

Regions were defined by the six official healthcare regions in Sweden: North, South, Stockholm-Gotland, South-East, Uppsala-Örebro, and West. Regions are composed of geographically neighboring county councils that co-operate in highly specialized healthcare, among other areas. The healthcare regions vary in population size between 0.8 and 2 million inhabitants [see Table 3 and Figure 4 in the electronic supplementary material (ESM)].

Patient characteristics included age and sex. Clinical characteristics were obesity, defined as body mass index (BMI) ≥30, presence of PsA, and clinical types or symptoms of psoriasis (nail psoriasis, non-palm pustular, palm pustular, general pustular, erythroderma, and acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau).

The PASI was used as a measure of disease severity. The PASI is based on the extent of skin involvement and ranges from 0 (no disease) to 72 (theoretical maximal disease) [25]. The patient view of disease impact was assessed using the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI). The DLQI score ranges from 0 (quality of life not impaired) to 30 (quality of life severely impaired).

Statistical Analysis

The proportion of patients who switched to biologics out of all patients on conventional systemics, the switch rate, was first calculated for each time period nationally and regionally. The difference between the highest and lowest regional switch rates was calculated. Significant differences in switch rates between regions in each time period were tested using the chi-squared test.

Logistic regression models were then used to estimate adjusted odds ratios (ORs) of switch to a biologic between healthcare regions in 2-year periods. ORs measure the likelihood of switch to a biologic in one region compared with a reference region. Since the Stockholm-Gotland region as a group had the largest number of patients of all regions, it was used as the reference region. A separate logistic regression was performed to estimate the likelihood of switch between regions for the entire period (2008–2015).

The models were adjusted for risk factors of psoriasis hypothesized to be associated with the prescription of biologics and/or stated criteria for biologics use in medical guidelines. Results were reported as ORs with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). ORs with a CI including one indicate that the null hypothesis of no association to switch to a biologic could not be rejected. A Wald test of joint significance was conducted to examine if the set of variables indicating region have significant explanatory power on the decision to switch to a biologic.

To impute missing DLQI scores, DLQI was regressed against hypothesized significant predictors of DLQI, such as PASI, age, and sex. The estimated coefficients from the regression model were used to predict scores. The model predicted scores replaced missing DLQI scores. Obesity was based on registered information on BMI, and people with missing BMI values were included as not obese.

Data analysis was performed using STATA (StataCorp, 2015; Stata Statistical Software: Release 14; College Station, TX, USA; StataCorp LP) and R (R Core Team, 2016; Version 3.3.0; Vienna, Austria; R Foundation for Statistical Computing) statistical packages.

Results

Patient and Clinical Characteristics

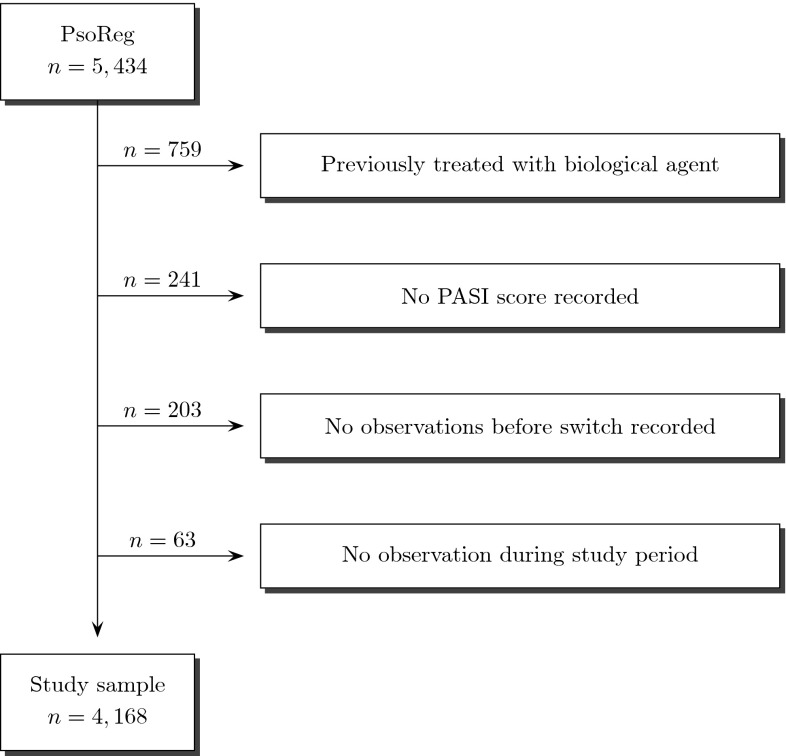

A total of 4168 unique biologic-naïve patients fulfilled the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). When examining registrations in 2-year periods, 1574 biologic-naïve patients had at least one registration in PsoReg in 2008–2009, 1936 in 2010–2011, 1959 in 2012–2013, and 1525 in 2014–2015.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of patients from the Swedish National Register for Systemic Treatment of Psoriasis (PsoReg) included in this analysis. PASI Psoriasis Area and Severity Index

Table 1 displays the clinical and demographic characteristics of biologic-naïve patients in each 2-year period. Over time, the patient sample increased in the proportion of males and median BMI, but decreased in median PASI and the proportion with PsA. Median age and DLQI were constant. In the latest period (2014–2015), the age of patients ranged from 5 to 94 years old and the median age was 55. Males composed 63% of the cohort, and 21% of patients reported PsA.

Table 1.

Clinical and demographic characteristics of biologic-naïve patients who remained on conventional systemic agents at their last observed contact and of those patients who switched to a biologic agent at the observation closest in time before the switch to a biologic occurred

| 2008–2009 | 2010–2011 | 2012–2013 | 2014–2015 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 1574 | 1936 | 1959 | 1525 |

| Male, n (%) | 935 (59) | 1,162 (60) | 1,179 (60) | 965 (63) |

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 55 (43–64) | 55 (43–65) | 55 (43–66) | 55 (43–66) |

| BMI, median (IQR) | 26.9 (24.2–30.5) | 27.1 (24.3–30.5) | 27.1 (24.2–30.8) | 27.1 (24.2–31.2) |

| PASI, median (IQR) | 4.0 (2.0–8.0) | 3.8 (2.0–7.2) | 3.5 (1.8–6.8) | 3.5 (1.8–6.9) |

| DLQI, median (IQR) | 3.0 (1.0–7.0) | 3.0 (1.0–7.0) | 3.0 (1.0−7.0) | 3.0 (1.0–7.0) |

| Psoriatic arthritis, n (%) | 438 (28) | 507 (26) | 454 (23) | 319 (21) |

| Healthcare region, n (%) | ||||

| Stockholm-Gotland | 653 (42) | 741 (38) | 654 (33) | 502 (33) |

| West | 344 (22) | 382 (20) | 461 (24) | 374 (25) |

| South | 189 (12) | 303 (16) | 363 (19) | 275 (18) |

| North | 244 (16) | 293 (15) | 229 (12) | 105 (7) |

| South-East | 72 (5) | 125 (6) | 140 (7) | 190 (12) |

| Uppsala-Örebro | 72 (5) | 92 (5) | 112 (6) | 88 (6) |

Notes: Percentage of patients in healthcare regions may not total 100 due to rounding

BMI body mass index, IQR interquartile range, PASI Psoriasis Area and Severity Index, DLQI Dermatology Life Quality Index

In terms of geographical distribution, the Stockholm-Gotland region held the greatest proportion of patients, followed by the Western region, over all periods. This reduced over time as more patients from outside the Stockholm-Gotland region entered the register. In the latest period (2014–2015), the Stockholm-Gotland region held 33% of patients, followed by the Western region (25%), Southern region (18%), South-Eastern region (12%), Northern region (7%), and lastly Uppsala-Örebro (6%).

Out of all 4168 patients, 9% were included in all four time periods, 17% in three time periods, 26% in two time periods, and 48% in one period. This corresponds to the frequency of registrations for each patient: 27% of patients had one registration, 29% had two to three, while 44% had four or more. About 6% of study patients had a missing DLQI value, while 5.5% had a missing BMI value.

DLQI Imputation

PASI, age, and sex carried statistically significant coefficients, with sex having the largest effect on predicted DLQI scores. Higher DLQI was associated with higher PASI scores and lower age. At most, 8% of DLQI scores were missing (n = 117) in the 2014–2015 period. Full regression estimates are given in Table 4 in the ESM.

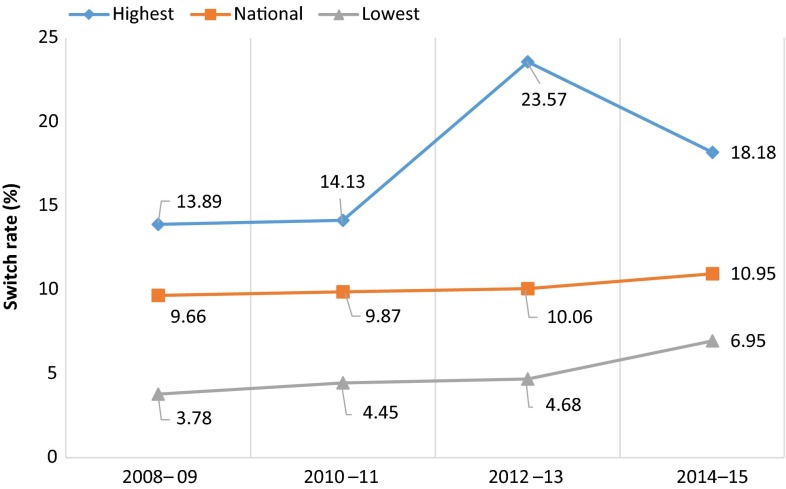

Proportion of Patients Switched to Biologics

Approximately 10% of patients on conventional systemics were switched to biologics during a 2-year period and this proportion increased over time (Fig. 2). The switch rate was 9.7% in 2008–2009 and grew to 11.0% in 2014–2015. A greater proportion of patients were switched in some regions and a lesser proportion in others. The difference between the regions with the highest and lowest switch rates were 10.1 percentage points (pp) in 2008–2009, 9.7 pp in 2010–2011, 18.9 pp in 2012–2013, and 11.2 pp in 2014–2015. Differences in switch rates by region were significant in each time period (p < 0.01). Table 2 reports switch rates for each healthcare region and for Sweden.

Fig. 2.

The proportion of patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis switched to biologics over time (switch rate), for Sweden and for the regions with the highest and lowest switch rates

Table 2.

The proportion of patients who switched to biologics out of all biologic-naïve patients on conventional systemics (switch rate) for each healthcare region and for Sweden

| 2008–2009 | 2010–2011 | 2012–2013 | 2014–2015 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stockholm-Gotland | 90/653 (13.78) | 80/741 (10.80) | 75/654 (11.47) | 47/502 (9.36) |

| West | 13/344 (3.78) | 17/382 (4.45) | 31/461 (6.72) | 26/374 (6.95) |

| Uppsala-Örebro | 10/72 (13.89) | 13/92 (14.13) | 25/112 (22.32) | 16/88 (18.18) |

| South | 13/189 (6.88) | 31/303 (10.23) | 17/363 (4.68) | 45/275 (16.36) |

| South-East | 7/72 (9.72) | 21/125 (16.80) | 33/140 (23.57) | 29/190 (15.26) |

| North | 19/244 (7.79) | 29/293 (9.90) | 16/229 (6.99) | 5/105 (9.76) |

| Sweden | 152/1574 (9.66) | 191/1936 (9.87) | 197/1959 (10.06) | 168/1525 (11.02) |

Using Chi-squared tests, statistically significant differences in switch rate were found between regions in each time period (p < 0.01)

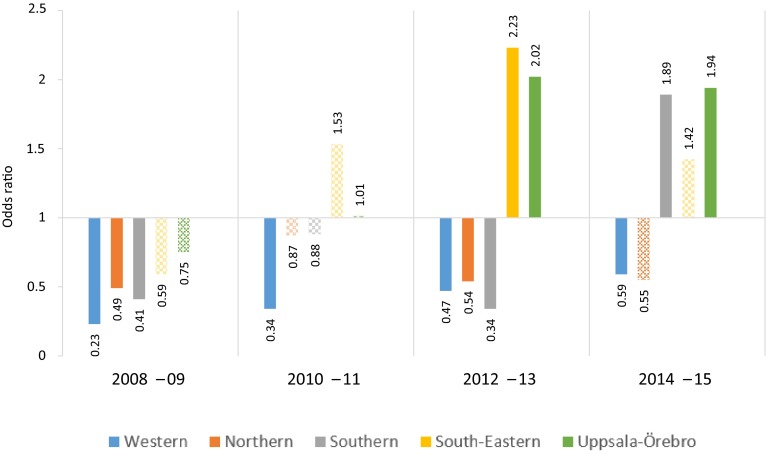

Adjusted Likelihood of Switch

The likelihood of switch to a biologic differed significantly between healthcare regions in each 2-year period (see Fig. 3). The Western, Northern, and Southern regions were less likely to switch patients compared to the reference region, Stockholm-Gotland, in the early years, particularly in 2008–2009. All regions except the Western region had similar switching patterns in 2010–2011, though in the following period (2012–2013), each region deviated from the Stockholm-Gotland region. Patients from the South-Eastern and Uppsala-Örebro regions were more than twice as likely to be switched compared to similar patients from the Stockholm-Gotland region. At the same time, patients from the Western and Southern regions were less than half as likely to be switched. In the latest period (2014–2015), the Western, Southern, and Uppsala-Örebro regions continued to have significantly different likelihood of switch. Indicator variables on healthcare regions were jointly significant as predictors of switch to a biologic in all periods (Wald test p < 0.01).

Fig. 3.

Adjusted odds ratios (ORs) from the logistic regression of switch to a biologic against healthcare regions whilst adjusting for disease severity, patient and clinical characteristics, and clinical types or symptoms of psoriasis for 2008–2009, 2010–2011, 2012–2013, and 2014–2015 periods. Hatched bars indicate statistically insignificant difference in ORs to the reference region, Stockholm-Gotland (OR = 1.00)

Other covariates were associated with the likelihood of switch to a biologic. As expected, the adjusted ORs of PASI were greater than one and statistically significant [OR (95% CI) above one] for all periods. The adjusted ORs for PsA were greater than one and statistically significant for 2008–2009 and 2010–2011. While the estimate of adjusted ORs for PASI increased in magnitude over time, the corresponding estimate for PsA became insignificant. DLQI did not carry significant adjusted ORs for any period. The adjusted ORs for the age variable were less than one and statistically significant [OR (95% CI) below one] in all periods.

For the entire registration period (2008–2015), the adjusted ORs for the Western (adjusted OR = 0.41, 95% CI 0.32–0.53), Northern (adjusted OR = 0.55, 95% CI 0.41–0.74), and Southern (adjusted OR = 0.70, 95% CI 0.54–0.89) regions were less than one and statistically different from the reference category. Full regression estimates for 2-year periods and the full registration period are given in the ESM.

Discussion

While the Swedish healthcare system has several measures against inequitable treatment access, our data showed that there are significant and persistent regional differences in biologics prescription in the case of psoriasis, also after adjusting for patient characteristics and standard measures of disease severity. This should motivate further investigations into reasons for the observed variation of access to biologics in Sweden and in other countries with goals of equitable healthcare access.

Switch to a biologic was more likely in some years than other years within a given region, though at the same time, the national switch rate was stable at approximately 10%. Over time, regional differences did not disappear, nor decrease in magnitude. A decade after the introduction of biologics in Sweden, these differences persist, suggesting that treatment options for patients with psoriasis depend on where care is received.

The main strength of this register-based study is that PsoReg allows for the possibility to adjust for disease impact in terms of PASI and DLQI. Clinical data are generally not available in administrative registries. Data used from PsoReg also encompass a long time period of 10 years, including time before patients were on biologics (if prescribed). Furthermore, PsoReg has nationwide coverage, with an estimated 65% of all Swedish patients with psoriasis on biologics enrolled. With these advantages, treatment patterns were described as they happened in real-world clinical practice, which enhances the external validity of the results.

Nonetheless, register-based research has inherent limitations, some of which are shared by other research designs. Confounding due to unobserved patient and physician preferences, for instance, may influence treatment adherence, patient quality of life, and likewise, the decision to prescribe biologics. Another limitation is the unavailability of information to ascertain data coverage and representativeness. As disease severity of patients in PsoReg is not registered elsewhere, there is insufficient data to externally validate how the register has tracked the actual rate of switches to biologics in psoriasis. Nevertheless, the research questions addressed in this study do not require full coverage. Our interest was to find patients in the register with similar characteristics and disease status but treated in different regions, and to see if they are equally likely to be prescribed biologics. The registration of patients using systemic treatments, conventional and/or biologics, in PsoReg is not likely to systemically differ by region given that PsoReg has a national platform and its inclusion criteria apply equally to all regions. A regression for the entire registration period was conducted to check whether the use of PsoReg over time may have affected results. As in our main analysis, notable regional differences were found over the entire period.

A few empirical studies have investigated medical practice variation within dermatology, and particularly in psoriasis care [26–28]. In rheumatology, a Swedish study based on the administrative register of prescribed drugs explored differences in the sale of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors, a subgroup of biologics, between county councils and healthcare regions in 2000 and 2009 [13]. The per capita sales of TNF inhibitors were about twice as high in the region with the highest sales compared to the region with the lowest sales. In that study, the Western region of Sweden had the lowest TNF inhibitor sales per capita (approximately €14 per capita) and the lowest proportion of people with rheumatoid arthritis using TNF inhibitors (11%). Even when adjusting for covariates, as conducted in our study, a lower likelihood of switch to a biologic in the Western region of Sweden was observed. The same pattern of regional variation appears for both psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis. When examining trends in recent years in this study, the Western region was still less likely to prescribe, though the gap has reduced. Interestingly, the reduction corresponds to a change in the treatment guidelines of the region implemented from 2014 onwards, where biologics could be initiated at an earlier stage than before [29, 30].

From an international perspective, the regional variation in the uptake of TNF inhibitors has been explored in rheumatology [31, 32]. Whereas significant differences were found in types of patients initiating TNF inhibitors in Canadian provinces, no significant differences were observed in UK healthcare regions.

The likelihood of switch to a biologic was not found to correlate with socioeconomic differences between the regions (see Table 3 in the ESM). It seems unlikely that the variation observed stems from regional differences in socio-economic status or differences in the composition of healthcare tax base. Other supply-side differences including characteristics of decision-making structures and capacity constraints have been identified as important for healthcare provision [33].

Yet, regional variation can be expected when novel therapies, such as biologics in the early 2000s, are introduced, as some regions and types of providers may adapt to new medical technology faster than others [34, 35]. The Stockholm-Gotland region could thus be considered as early adopters of biologics since patients in the region were more likely to switch early on. Part of the supply-side source of variation would be expected to diminish over time as biologics become fully implemented in psoriasis care. Nevertheless, more than a decade later, regional differences in biologics use persist, suggesting that patients may have inequitable access to biologics depending on where they live. Not only does it makes psoriasis care less patient-centered [36], it also creates a situation that is at odds with the aim of providing equal access to care. It is therefore important to further review evidence and experience from national registries such as PsoReg to investigate prescription trends in psoriasis. The effect of new biosimilars on future prescription trends, for instance, could be investigated.

The Swedish healthcare system may be viewed as a testing case for assessing equitable access to biologics. While several measures are in place to combat disparities in healthcare delivery, geographical differences were persistent. Further improvements could be made to promote equitable access in psoriasis care.

Conclusions

Geographical differences in biologics prescription persist after adjusting for patient characteristics and disease severity, suggesting that treatment options for patients with psoriasis depend on where care was received. This calls for further improvement towards delivering equitable psoriasis care.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the patients and healthcare professionals contributing to the advancement of clinical practice through participation in quality registries such as PsoReg.

Compliance with ethical standards

Ethical approvals

Research was done in adherence with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the study was approved by the Umeå Ethical Review Board. Patients were recruited after informed consent was obtained. Both data and consent were collected electronically to ensure an effective logistic in this nationwide project.

Funding

PsoReg receives financial support from the Swedish Board of Health and Welfare, Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions, and Västerbotten County Council. The research has received financial support from Abbvie, Janssen Cilag, Leo Pharma, Novartis, and Pfizer. Sponsors had no access to data. The authors had full independence regarding data collection, manuscript preparation, decision to publish, study design, interpretation, and analysis.

Conflict of interest

M. Schmitt-Egenolf is the manager of PsoReg and responsible for dermatology in the project management for the national guidelines for psoriasis at the Swedish Board of Health and Welfare. P. S. Calara, R. Althin, K. Steen Carlsson have no further conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Lofvendahl S, Theander E, Svensson A, Carlsson KS, Englund M, Petersson IF. Validity of diagnostic codes and prevalence of physician-diagnosed psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis in southern Sweden—a population-based register study. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e98024. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parisi R, Symmons DP, Griffiths CE, Ashcroft DM, Identification and Management of Psoriasis and Associated ComorbidiTy (IMPACT) Project Team et al. Global epidemiology of psoriasis: a systematic review of incidence and prevalence. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133(2):377–385. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brandrup F, Green A. The prevalence of psoriasis in Denmark. Acta Derm Venereol. 1981;61(4):344–346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kavli G, Forde OH, Arnesen E, Stenvold SE. Psoriasis: familial predisposition and environmental factors. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1985;291(6501):999–1000. doi: 10.1136/bmj.291.6501.999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hägg D. Psoriasis in Sweden: observational studies from an epidemiological perspective. Umeå: Umeå University; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barzi S, Befrits G, Bergman B, Bruchfeld J, Ettarp L, Flytström I, et al. Läkemedelsbehandling av psoriasis—Ny rekommendation. Information from The Medical Products Agency; 2011.

- 7.Norlin JM, Steen Carlsson K, Persson U, Schmitt-Egenolf M. Switch to biological agent in psoriasis significantly improved clinical and patient-reported outcomes in real-world practice. Dermatology. 2012;225(4):326–332. doi: 10.1159/000345715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Norlin JM. Effectiveness and costs of new medical technologies: register-based research in psoriasis. Umeå: Umeå universitet. Umeå University Medical Dissertations; 2013.

- 9.Geale K, Henriksson M, Schmitt-Egenolf M. Evaluating equality in psoriasis healthcare: a cohort study of the impact of age on prescription of biologics. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174(3):579–587. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hagg D, Eriksson M, Sundstrom A, Schmitt-Egenolf M. The higher proportion of men with psoriasis treated with biologics may be explained by more severe disease in men. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e63619. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calara PS, Norlin JM, Althin R, Carlsson KS, Schmitt-Egenolf M. Healthcare provider type and switch to biologics in psoriasis: evidence from real-world practice. BioDrugs. 2016;30(2):145–151. doi: 10.1007/s40259-016-0163-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jonsson B, Kobelt G, Smolen J. The burden of rheumatoid arthritis and access to treatment: uptake of new therapies. Eur J Health Econ. 2008;8(Suppl 2):S61–S86. doi: 10.1007/s10198-007-0089-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neovius M, Sundstrom A, Simard J, Wettermark B, Cars T, Feltelius N, et al. Small-area variations in sales of TNF inhibitors in Sweden between 2000 and 2009. Scand J Rheumatol. 2011;40(1):8–15. doi: 10.3109/03009742.2010.493895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brommels M, Hansson J, Granström E, Wåhlin E. Professionals, payments and pens—regional variation in the utilisation of medicines. Stockholm: Medical Management Centrum (MMC), Karolinska Institute; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wennberg JE. Unwarranted variations in healthcare delivery: implications for academic medical centres. BMJ. 2002;325(7370):961–964. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7370.961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wennberg JE, Fisher ES, Skinner JS. Geography and the debate over Medicare reform. Health Aff (Millwood). 2002;Suppl Web Exclusives:W96–114. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Davis K, Stremlikis K, Squires D, Schoen C. Mirror, mirror on the wall: how the performance of the U.S. Health Care System compares internationally, 2014 update: the commonwealth fund; 2014.

- 18.Nolte E, McKee CM. Measuring the health of nations: updating an earlier analysis. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27(1):58–71. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.SKL. Svensk sjukvård i internationell jämförelse. Stockholm: Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions (SKL); 2015.

- 20.Björnberg A. Euro Health Consumer Index 2015. Stockholm: Health Consumer Powerhouse; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 21.The Conference Board of Canada. International Ranking—Canada benchmarked against 15 countries; 2012. http://www.conferenceboard.ca/hcp/details/health.aspx. Cited 29 Sept 2016.

- 22.Swedish Government [Sveriges Riksdag]. Swedish Health Care Act. In: Swedish Government [Sveriges Riksdag], vol. 763. Stockholm; 1982.

- 23.Schmitt-Egenolf M. Psoriasis therapy in real life: the need for registries. Dermatology. 2006;213(4):327–330. doi: 10.1159/000096196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmitt-Egenolf M. PsoReg—the Swedish registry for systemic psoriasis treatment. The registry’s design and objectives. Dermatology. 2007;214(2):112–117. doi: 10.1159/000098568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fredriksson T, Pettersson U. Severe psoriasis—oral therapy with a new retinoid. Dermatologica. 1978;157(4):238–244. doi: 10.1159/000250839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Corallo AN, Croxford R, Goodman DC, Bryan EL, Srivastava D, Stukel TA. A systematic review of medical practice variation in OECD countries. Health Policy. 2014;114(1):5–14. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gyulai R, Bagot M, Griffiths CE, Luger T, Naldi L, Paul C, et al. Current practice of methotrexate use for psoriasis: results of a worldwide survey among dermatologists. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29(2):224–231. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Radtke MA, Augustin J, Blome C, Reich K, Rustenbach SJ, Schäfer I, et al. How do regional factors influence psoriasis patient care in Germany? Journal Der Deutschen Dermatologischen Gesellschaft. 2010;8(7):516–524. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2010.07358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pharmaceutical Committee of the Western Region—Skin Therapy Group. Regional Medical Guidelines—Psoriasis [Regional Medicinsk riklinje - Psoriasis]; 2011. http://epi.vgregion.se/upload/L%C3%A4kemedel/MR/MR%20Psoriasis_TT.pdf. Cited 22 July 2016.

- 30.Pharmaceutical Committee of the Western Region—Skin Therapy Group. Regional Medical Guidelines—Psoriasis [Regional Medicinsk riklinje—Psoriasis]; 2014.

- 31.Pease C, Pope JE, Thorne C, Haraoui BP, Truong D, Bombardier C, et al. Canadian variation by province in rheumatoid arthritis initiating anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy: results from the optimization of adalimumab trial. J Rheumatol. 2010;37(12):2469–2474. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.091447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Choy E, Taylor P, McAuliffe S, Roberts K, Sargeant I. Variation in the use of biologics in the management of rheumatoid arthritis across the UK. Curr Med Res Opin. 2012;28(10):1733–1741. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2012.731388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Skinner J. Causes and consequences of regional variations in health care. In: Pauly MV, McGuire TG, Barros PP, editors. Handbook of health economics. North Holland: Elsevier B.V; 2012. pp. 45–93. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Skinner J, Staiger D. Technology adoption from hybrid corn to beta blockers: working paper 11251. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2005. http://www.nber.org/papers/w11251.

- 35.Skinner J, Staiger D. Technology diffusion and productivity growth in health care: Working Paper 14865. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2009. http://www.nber.org/papers/w14865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Mulley AG. Improving productivity in the NHS. BMJ. 2010;341:c3965. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c3965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.