Abstract

Background

Predicting outcome in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) using pre-treatment predictors has been the cornerstone of management. Post-treatment prognostic factors are increasingly evaluated.

Methods

Among 280 younger patients treated with intermediate dose cytarabine (total of ≥ 5 g/m2) and idarubicin based induction chemotherapy who achieved remission, 186 were assessed for MRD using an 8-color multi-parameter flow cytometry (MFC) panel performed on bone marrow specimens, with a sensitivity of 0.1% or higher.

Results

166 patients had available samples at 1-2 months post induction at the time of achieving complete remission (CR) and 79% became negative for MRD, with MRD-negative status associated with improvement in relapse free survival (RFS) (p= 0.0002) and overall survival (OS) (p= 0.0002). 116 were evaluated for MRD status during consolidation and 86% were negative with a MRD-negative status associated with a significant improvement in RFS (p<0.0001) and OS (p<0.0001). 69 patients were evaluated for MRD status after completion of all therapy and 84% were negative with a MRD-negative status associated with improvement in RFS (P<0.0001) and OS (P<0.0001). On multivariate analysis including age, cytogenetics, achieving CR vs. CRp/CRi, and MRD, achieving MRD-negative status was the most important independent predictor of RFS and OS at response (p=0.008 and p=0.0008, respectively), during consolidation (p<0.0001 for both), or at completion of therapy (p<0.0001 and p=0.002).

Conclusion

Achieving MRD-negative status by MFC is associated with a highly significant improvement in the outcome of younger patients with AML receiving ara-C plus idarubicin-based induction and consolidation regimens.

Keywords: Acute myeloid leukemia, Minimal residual disease, prognostic, survival, relapse-free survival

Introduction

Predicting the outcome of therapy in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) treated with cytotoxic chemotherapy regimens has been an important aspect of therapeutic decision making particularly related to selection of post-remission therapy.1 This prediction has been mainly based on pre-treatment factors related to the patients' ability to tolerate intensive therapy as well as disease-related variables such as karyotype, molecular features, as well as other biological features hitherto determined to be associated with resistance to the standard cytarabine plus anthracycline regimens.2-4

Although response to therapy and particularly achievement of morphologic complete remission (CR) has been clearly associated with better outcomes, few other measures of leukemic cell drug sensitivity such as early blast clearance or early marrow response have been consistently used to determine the likely durability of response.5-7 This is in contrast to studies in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) where early measures of drug sensitivity such as early response to chemotherapy have been commonly utilized to determine the need for intensification of therapy.8, 9 This may be partly due to higher likelihood of inherent leukemia resistance to cytotoxic agents and lower probability that intensification is well-tolerated and improves the outcome in adult AML. On the other hand, with the high response rates achieved after intensive chemotherapy regimens, pediatric investigators have begun to increasingly rely on markers of minimal residual disease (MRD) for selection of patients with ALL and AML for further intensification.10, 11 In the adult population, it can be argued that MRD assessment is of more value in the younger patients who can tolerate more intensive induction therapy and have a higher likelihood of achieving CR and who are more likely to be candidates for allogeneic stem cell transplant.

Recent availability of sensitive assays that can detect residual, submicroscopic leukemia based on leukemia-specific features such as aberrant immuno-phenotype or abnormal molecular markers, as well as the prospects of future availability of novel agents that are more disease-specific and potent, have re-kindled interest in MRD assessment in adult AML.12-15 Although prior studies have established the value of MRD assessment in the adult patients with AML treated with cytotoxic regimens, its value in prognostication and post-remission therapeutic decision making as well as the best assay to detect it continues to be debated.12 Herein, we report data on adult patients with AML treated at our institution with intensive chemotherapy regimens and examine the prognostic value of MRD detection using multi-parameter flow cytometry.

Methods

Patients

From April 2007 to June 2015, 318 patients with newly diagnosed AML were treated with one of four regimens containing intermediate dose (≥ 5 g/m2 total dose) of cytarabine in addition to idarubicin for induction and consolidation courses. All patients were younger than 65 years of age, or if older had to have ELN favorable cytogenetics/molecular features and were deemed fit to receive chemotherapy. Among these 280 (88%) achieved CR or CR with incomplete recovery of platelet count (CRp) or peripheral blood counts (CRi) defined by the revised international working group (IWG) criteria.16 One hundred and eighty six (58%) had available flow MRD analysis and are subject of this study. Ninety four patients including 62 (66%) with core binding factor leukemia (who were typically monitored by molecular testing alone) did not have available flow MRD analysis. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of these patients. All patients were treated on clinical trials approved by the MD Anderson Cancer Center Institutional Review Board and written informed consent was obtained from all patients before entry into the studies in accordance to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Table 3b. Multivariate Cox regression analysis of covariates for overall survival.

| Parameter | Hazard ratio (95% confidence interval) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| At Response (1 – 2 months from Therapy Initiation) (N=166) | ||

|

| ||

| Age | 1.05 (1.00, 1.09) | 0.05 |

| Cyto (Fav vs. Others) | 0.07 (0.01, 0.57) | 0.01 |

| Response (CRi/CRp vs. CR) | 1.06 (0.34, 3.30) | 0.93 |

| MRD at CR | 5.17 (1.98, 13.49) | 0.0008 |

|

| ||

| During Consolidation (3 – 7 Months from Therapy Initiation) (N=116) | ||

|

| ||

| Age | 1.00 (0.96, 1.04) | 0.89 |

| Cyto (Fav vs. Others) | 0.42 (0.09, 1.97) | 0.27 |

| Response (CRi/CRp vs. CR) | 0.88 (0.22, 3.46) | 0.85 |

| MRD at 3-7 Months | 12.57 (3.94, 40.07) | <0.0001 |

|

| ||

| At Completion of Therapy (≥ 8 Months from Therapy Initiation) (N=69)* | ||

|

| ||

| Age | 1.01 (0.97, 1.06) | 0.60 |

| Cyto (Fav vs. Others) | 0.91 (0.14, 5.75) | 0.92 |

| MRD at ≥ 8 Months | 10.19 (2.34, 44.34) | 0.002 |

The effect of response cannot be estimated because among the 65 evaluable patients, only 1 patient had CRp, the remaining 64 patients all had CR.

Treatment regimens and sample collection

The details of the various treatment regimens have been previously published.17, 18 Briefly, in all regimens, the induction course contained idarubicin (I)(total dose 12 - 30 mg/m2) as well as intermediate dose cytarabine (A) (total dose 5 - 10 g/m2). In the FIA regimen, fludarabine 30 mg/m2 daily × 5 days was given in addition to IA. Similarly, in the CIA and CLIA regimens, clofarabine 15 mg/m2 daily × 5 days and cladribine 5 mg/m2 daily × 5 days were administered in addition to IA. In the FLAG-Ida regimen, fludarabine 30 mg/m2 daily × 5 as well as GCSF 5 μg/kg were included in addition to IA. Patient outcomes in terms of survival and relapse-free survival were similar for the FIA, CIA, CLIA regimens; the FLAG-Ida regimen was used almost entirely for patients with favorable risk cytogenetics and as such is expected to be associated with better outcomes. In all the above regimens consolidation consisted of up to 6 cycles of attenuated doses of the same agents. A summary of the treatment regimens is shown in Supplemental Table 1.

Response Definitions

Response assessment was based on the revised criteria defined by the International Working Group for AML.16 To achieve CR, patients needed to have less than 5% blasts by morphological assessment of the bone marrow specimen together with an absolute neutrophil count ≥ 1,000/μL and platelet count ≥ 100,000/μL in the peripheral blood with no evidence of extramedullary disease. Definition of CRp met the above criteria but with platelet count < 100,000/μL whereas the definition of CRi met the above criteria but with absolute neutrophil count <1,000/μL or platelet count < 100,000/μL.16

MRD analysis by flow cytometry

MRD assessment by multi-parameter flow cytometry (MFC) was performed on whole bone marrow (BM) specimens using a standard stain-lyse-wash procedure with ammonium chloride lysis. 1×106 cells were stained per analysis tube, and data were acquired on at least 2×105 cells when specimen quality permitted. Data on standardized 7- to 8-color staining combinations were acquired on FACSCanto II cytometers using FACSDiva software (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using FCS Express (De Novo Software). Several different tube configurations were used through the course of the study, all with staining for CD2, CD4, CD5, CD7, CD13, CD14, CD15, CD19, CD33, CD34, CD38, CD45, CD56, CD64, CD117, CD123, and HLA-DR. All tubes included CD34 and CD45. Both CD34+ cells and a broader gate including CD45 dim mononuclear cells and monocytes were analyzed in parallel for all cases.

MRD was identified in comparison with the known patterns of antigen expression by normal maturing myeloid precursors and monocytes as previously described.19, 20 Specimens for comparison included normal and regenerating marrows. MRD was quantitated as a percentage of total leukocytes, after exclusion of most RBC precursors by forward scatter. A distinct cluster of at least 20 cells showing altered expression of at least two antigens was regarded as an aberrant population, yielding an optimal sensitivity of 1 in 104 cells, or 0.01%. For cases with significant phenotypic overlap between leukemic blasts and normal myeloid precursors or monocytes, the sensitivity was lower, with an average sensitivity for all cases estimated at 0.1%. All specimens with positive results were included for analysis of clinical outcomes. Specimens with negative results but with suboptimal cell counts were excluded. When available, the phenotypic profiles of pre-treatment blasts were compared to specimens submitted for MRD testing.

Statistical analysis

Patient characteristics were summarized using frequency (%) for categorical variables and median (range) for continuous variables. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time interval between treatment initiation date and the date of death due to any cause. Patients alive were censored at the date of undergoing allogeneic stem cell transplant or last follow-up date. Relapse-free survival (RFS) is defined as the time interval between response date and the date of disease relapse or date of death due to any cause, whichever occurred first. Patients remaining alive and in continued remission were censored at the date of transplant if they underwent an allogeneic stem cell transplant or at the last follow-up date. The probabilities of OS and RFS were estimated using the method of Kaplan and Meier.21 Cox proportional hazards regression models were fit to assess the association between OS or RFS and patient characteristics.22 We used the method described by Gooley et al to estimate the cumulative incidence of relapse considering death as a competing event.23 All statistical analyses were conducted in SAS and Splus.

Results

Patient characteristics and disposition

Table 1 summarizes the patient characteristics. All patients were diagnosed as having AML based on the World Health Organization criteria of having ≥ 20% blasts in the pre-treatment bone marrow or peripheral blood.1 The median age of the cohort of 186 patients was 51 years (range, 17-77 years); only 6 (3%) patients were older than 65 and all had European LeukemiaNet favorable disease.4 The median white blood count at diagnosis was 4.7 × 109/L (Range, 0.5-103 × 109/L). Cytogenetics were favorable risk in 34 (18%), intermediate risk in 115 (62%) and adverse in 27 (15%) and was not available in 10 (5%) patients. 174 (94%) achieved CR with 11 (6%) achieving CRp and 1 (<1%) achieving CRi. Among them 174 (94%) achieved their response after 1 course of induction and 12 (6%) required at least 2 courses. 67 (36%) patients underwent an allogeneic stem cell transplant in first CR. Overall, 47 (25%) patients have relapsed or died with a median follow-up of 17 months (range, 1.2 – 77.4 months) for the survivors. The median relapse free survival (RFS) for the entire population has not been reached (range, 0.4 – 76.5 months) and the median overall survival is 60.8 months (range, 1.2 – 77.4 months)(Supplemental Figure 1). Among the patients who were transplanted in first CR, 13 have relapsed and 45 are surviving in CR (9 died in CR post-transplant). The last MRD evaluation was positive in 10 and negative in 56 (and not available in 1) among the transplanted patients with no difference in survival post-transplant between the two groups (p=0.8).

The characteristics of the 94 patients seen and treated during the same period who were not included in the study due to the lack of availability of MRD data are also shown in Table 1. The majority (66%) had favorable risk cytogenetics and as such were monitored by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis of the relevant fusion transcripts and not by flow cytometry. Similarly, 61 (65%) of this cohort were treated with the FLAG-Ida regimen which was specifically designed for this subset.

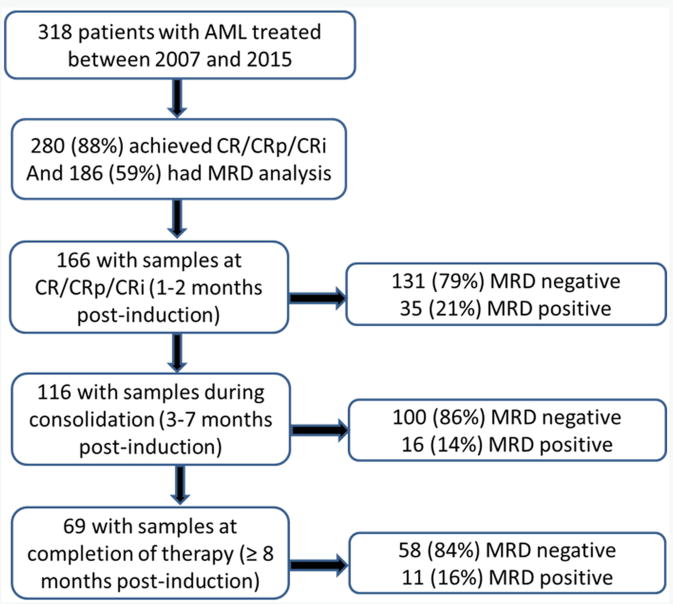

Among the 186 patients who achieved CR/CRp/CRi and had MRD analysis, 166 patients had available samples at 1-2 months post induction at the time of achieving complete remission (CR) and 79% became MRD negative (Figure 1). 116 were evaluated for MRD status during consolidation (after a median of 2 cycles of consolidation, range 1 to 5) and 86% were negative. 69 patients were evaluated for MRD status after completion of all therapy and 84% were negative (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Patient disposition and sample availability.

Predictors of outcome

We evaluated the potential predictors of RFS and OS including the known covariates such as patients' age, white blood cell count (WBC) at presentation, cytogenetics, as well as MRD at various time-points. On univariate analysis, cytogenetics (favorable vs. others), percentage of bone marrow blasts at diagnosis, type of response (CR vs. CRi/CRp) and type of therapy (FLAG-Ida vs. CLIA/CIA/FIA) as well as achievement of negative MRD at all the 3 time points indicated, were factors predictive of a better outcome for relapse-free survival and overall survival (Tables 2a and 2b). The type of therapy was confounded by cytogenetics as the FLAG-Ida regimen was specifically used in patients with favorable risk cytogenetics (Supplemental Table 2).

Table 2a.

Univariate Cox regression analysis for relapse-free survival.

| Covariate | HR | 95% CI | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.02 | 0.99 | 1.05 | 0.128 |

| log(WBC) | 0.94 | 0.72 | 1.22 | 0.622 |

| HGB | 1.05 | 0.83 | 1.34 | 0.672 |

| log(PLT) | 0.94 | 0.66 | 1.33 | 0.712 |

| log(Blast) | 0.93 | 0.75 | 1.15 | 0.509 |

| log(mono) | 1.02 | 0.78 | 1.34 | 0.863 |

| log(neutrophils) | 1.15 | 0.87 | 1.53 | 0.324 |

| promyelocytes | 1.09 | 0.58 | 2.06 | 0.781 |

| albumin | 0.80 | 0.43 | 1.48 | 0.478 |

| log(LDH) | 1.03 | 0.66 | 1.60 | 0.910 |

| bilirubin | 1.27 | 0.59 | 2.76 | 0.545 |

| creatinine | 0.60 | 0.15 | 2.45 | 0.476 |

| BM Blast | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.036 |

| Cytogenetics = Favorable (vs. Others) | 0.24 | 0.08 | 0.67 | 0.007 |

| MR1-2 (Positive vs. Negative) | 3.24 | 1.57 | 6.68 | 0.002 |

| MR3-7 (Positive vs. Negative) | 75.15 | 15.02 | 375.87 | <0.001 |

| MR8+ (Positive vs. Negative) | 14.58 | 5.03 | 42.25 | <0.001 |

| Response=CRp or CRi (vs. CR) | 5.21 | 2.15 | 12.62 | 0.0003 |

| FLT3 ITD positive (vs. Other) | 1.41 | 0.63 | 3.17 | 0.401 |

| FLT3 ITD negative/NPM1 positive (vs. Other) | 0.60 | 0.23 | 1.60 | 0.310 |

| Treatment = CIA (vs. FLAG) | 3.93 | 1.38 | 11.20 | 0.010 |

| Treatment = CLIA (vs. FLAG)* | <0.001 | <0.001 | NA | 0.991 |

| Treatment = FAI (vs. FLAG) | 2.66 | 0.75 | 9.50 | 0.131 |

Not estimable due to no events (i.e., relapse or death) in the CLIA group due to short follow-up. The FLAG regimens was used only for patients with CBF leukemia confounding the outcomes.

Table 2b.

Univariate Cox regression analysis for overall survival.

| Covariate | HR | 95% CI | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.02 | 0.99 | 1.04 | 0.253 |

| log(WBC) | 0.89 | 0.66 | 1.20 | 0.446 |

| HGB | 1.05 | 0.82 | 1.35 | 0.675 |

| log(PLT) | 1.07 | 0.74 | 1.54 | 0.737 |

| log(Blast) | 0.86 | 0.68 | 1.10 | 0.236 |

| log(monocytes) | 0.95 | 0.71 | 1.28 | 0.753 |

| log(neutrophils) | 1.14 | 0.83 | 1.57 | 0.431 |

| promyelocytes | 1.34 | 0.75 | 2.43 | 0.325 |

| albumin | 0.94 | 0.50 | 1.76 | 0.839 |

| log(LDH) | 1.20 | 0.73 | 1.96 | 0.474 |

| bilirubin | 1.10 | 0.48 | 2.54 | 0.818 |

| creatinine | 0.54 | 0.12 | 2.49 | 0.430 |

| BM Blast | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.058 |

| Cytogenetics = Favorable (vs. Others) | 0.14 | 0.03 | 0.58 | 0.007 |

| MR1-2 (Positive vs. Negative) | 4.28 | 1.85 | 9.90 | 0.001 |

| MR3-7 (Positive vs. Negative) | 15.11 | 5.43 | 42.05 | <0.001 |

| MR8+ (Positive vs. Negative) | 10.97 | 3.27 | 36.81 | <0.001 |

| Response=CRp or CRi (vs. CR) | 3.14 | 1.09 | 9.04 | 0.034 |

| FLT3 ITD positive (vs. Other) | 1.98 | 0.82 | 4.78 | 0.130 |

| FLT3 ITD negative/NPM1 positive (vs. Other) | 0.57 | 0.19 | 1.69 | 0.310 |

| Treatment = CIA (vs. FLAG) | 6.62 | 1.57 | 27.85 | 0.010 |

| Treatment = CLIA (vs. FLAG)* | <0.001 | <0.001 | NA | 0.993 |

| Treatment = FAI (vs. FLAG) | 4.45 | 0.81 | 24.50 | 0.09 |

Not estimable due to no events (i.e., death) in the CLIA group due to short follow-up. The FLAG regimens was used only for patients with CBF leukemia confounding the outcomes.

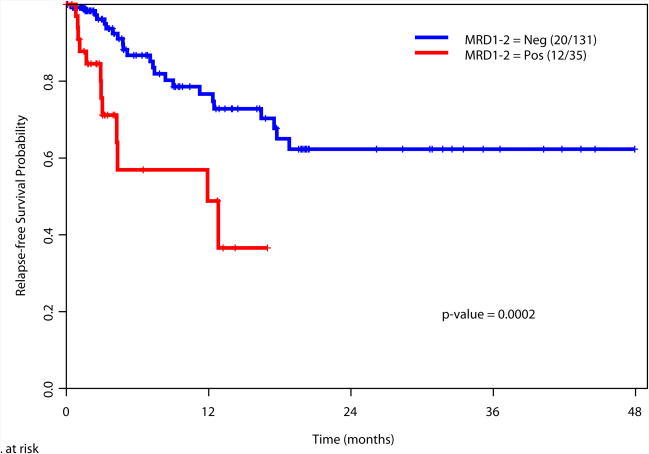

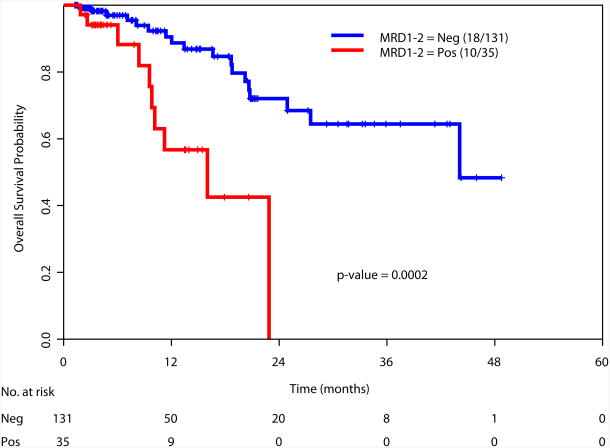

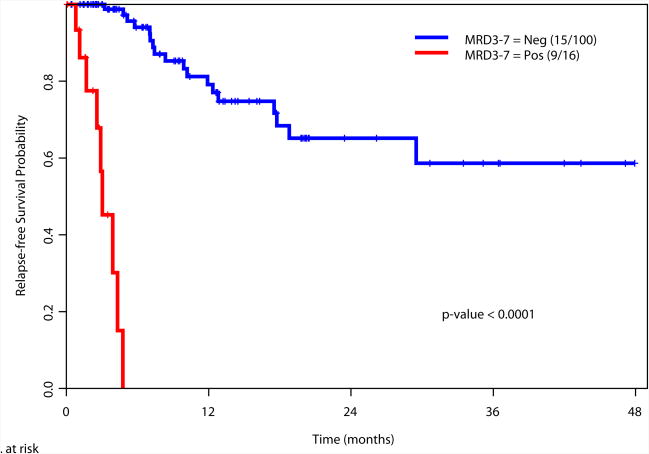

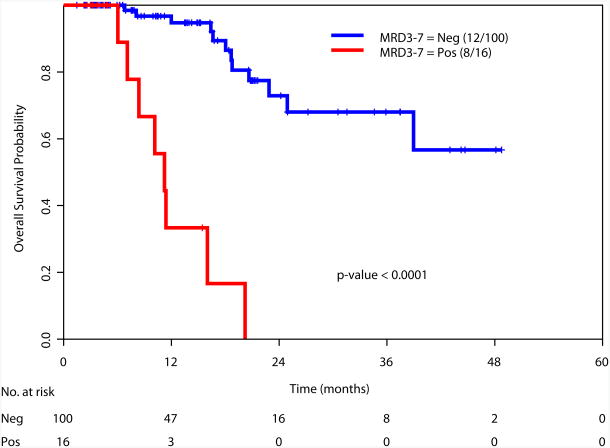

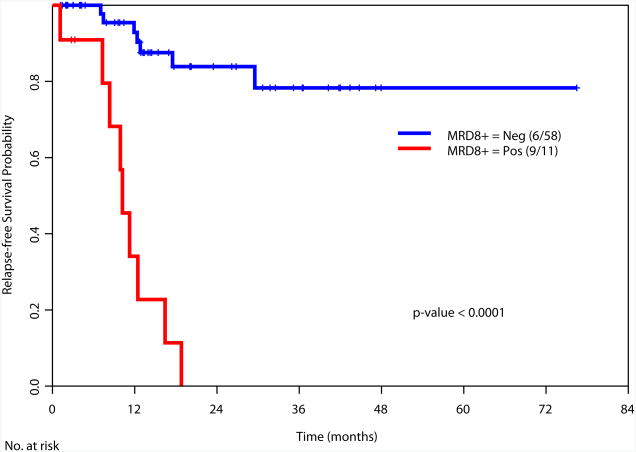

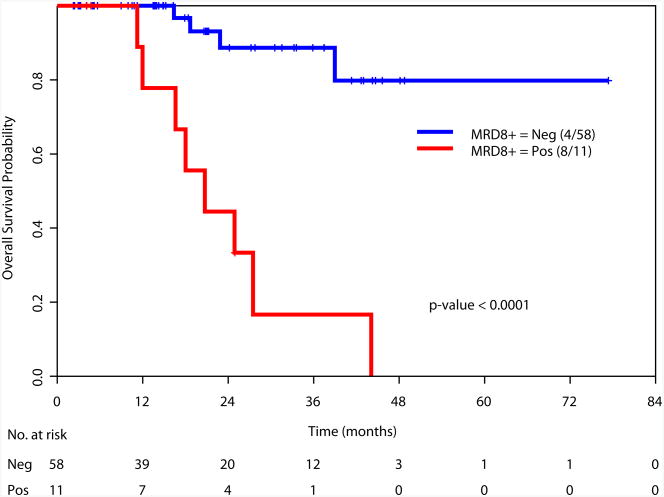

Achievement of a MRD-negative state at all the time points investigated [at the time of achieving response (1-2 months after start of therapy), during consolidation (3-7 months after start of therapy), and after completion of all therapy (8+ months after start of therapy)] was associated with a significant improvement in RFS and OS (Figure 2). We also examined the prognostic value of achieving an MRD negative state in the subgroup of patients with intermediate risk cytogenetics. Again, achieving MRD negativity at CR, during consolidation and after completion of therapy was associated with a significantly better RFS and OS (Supplemental Figure 2). We did not perform this analysis in the favorable and adverse cytogenetics subgroups due to the limited numbers of patients in these subsets (N=34 and N=27, respectively).

Figure 2.

a. Relapse-free survival based on MRD status at response (1-2 months after start of therapy)

b. Overall survival based on MRD status at response (1-2 months after start of therapy)

c. Relapse-free survival based on MRD status during consolidation therapy (3-7 months after start of therapy)

d. Overall survival based on MRD status during consolidation (3-7 months after start of therapy)

e. Relapse-free survival based on MRD status at completion of therapy (8+ months after start of therapy)

f. Overall survival based on MRD status at completion of therapy (8+ months after start of therapy)

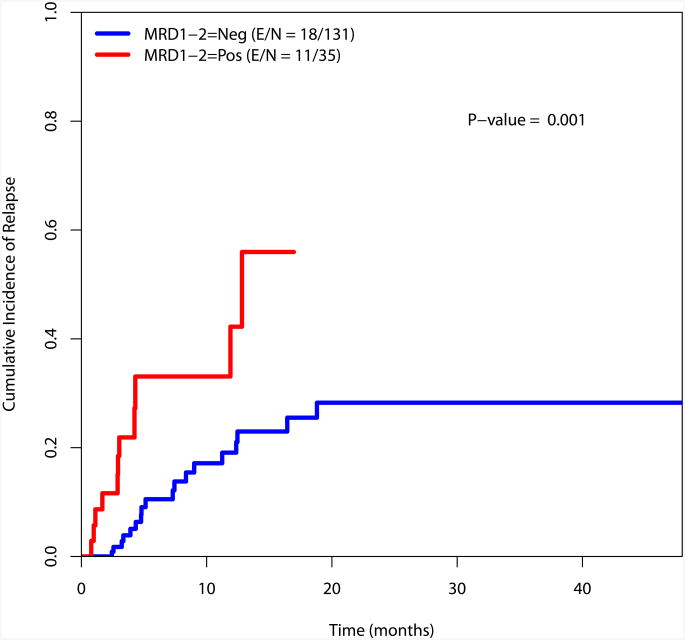

Cumulative incidence of relapse

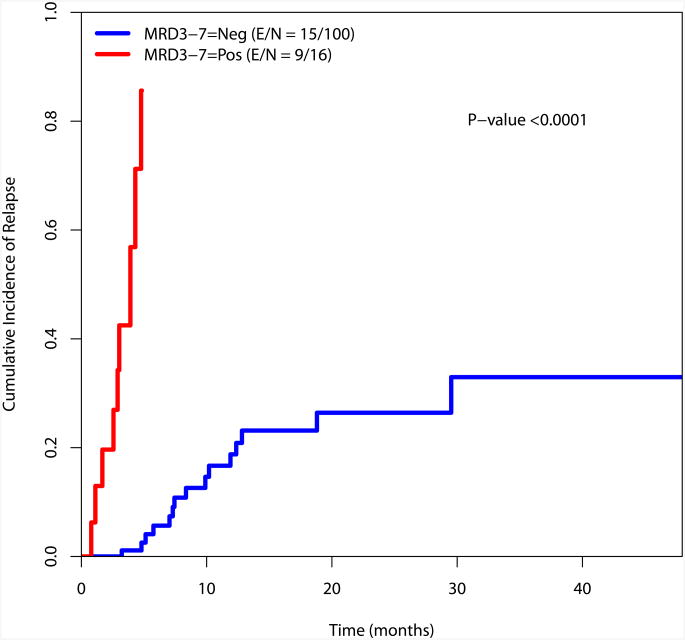

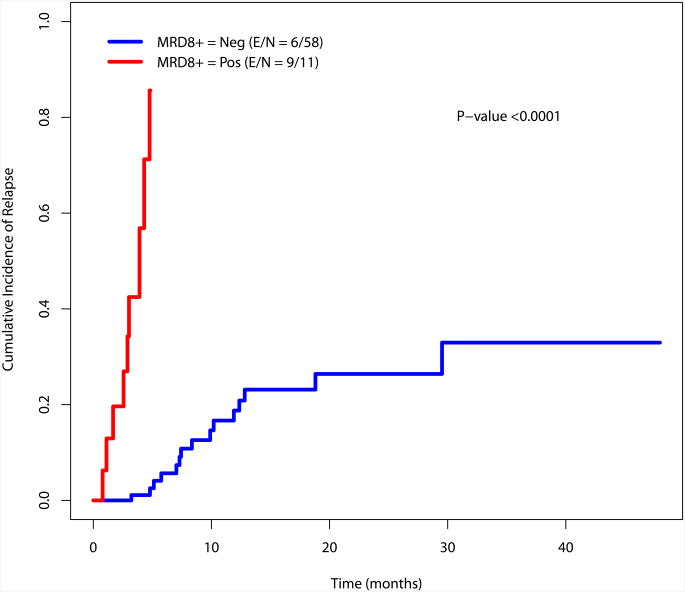

The cumulative incidence of relapse was estimated using the method by Gooley et al and is presented in Figure 3.23 There is a significant difference in the incidence of relapse for the MRD negative and MRD positive cohorts at the recorded time points (at response, during consolidation and at the completion of consolidation)(Figure 3).

Figure 3.

a. Cumulative incidence of relapse by MRD status at response

b. Cumulative incidence of relapse by MRD status during consolidation

c. Cumulative incidence of relapse by MRD status at completion of therapy

When patients in the intermediate risk cytogenetic category (N=105) were considered, there was also a significant difference in the cumulative incidence of relapse between patients who were MRD negative or positive at the time of achieving response as well as during consolidation and after completion of therapy (Supplemental Figure 3). Again, this analysis was not performed for the favorable and poor risk groups given their small sample size (N=34 and N=27, respectively).

Outcome prediction by MRD in relation to other covariates

We then examined the value of MRD status at response, during consolidation and after completion of therapy in predicting RFS and OS in relation to other known prognostic covariates. At the time of achieving response (1-2 months after start of therapy), data was available for 166 patients. Multivariate analysis including age, cytogenetics (favorable vs. others), type of response, and MRD status as covariates demonstrated cytogenetics (p=0.02) and MRD positive status (p=0.008) as the only significant t predictors of RFS (Table 3a). Similar analysis for OS, indicated age (p=0.05), cytogenetics (p=0.01) and MRD status (p=0.0008) as the important predictors of OS (Table 3b). Multivariate analysis performed at other time points (during consolidation and after completion of therapy) showed MRD status as the only statistically significant predictor for RFS (p<0.0001 for both time points) and for OS (p<0.0001 and p=0.002, respectively) (Table 3a and 3b).

Table 3a. Multivariate analysis of covariates for relapse-free survival.

| Parameter | Hazard ratio (95% confidence interval) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| At Response (1 – 2 months from Therapy Initiation) (N=166) | ||

|

| ||

| Age | 1.03 (1.00, 1.07) | 0.08 |

| Cyto (Fav vs. others) | 0.24 (0.07, 0.81) | 0.02 |

| Response (CRi/CRp vs. CR) | 2.39 (0.92, 6.24) | 0.07 |

| MRD at CR | 2.83 (1.31, 6.09) | 0.008 |

|

| ||

| During Consolidation (3 – 7 Months from Therapy Initiation) (N=116) | ||

|

| ||

| Age | 1.00 (0.97, 1.04) | 0.82 |

| Cyto (Fav vs. others) | 0.46 (0.15, 1.42) | 0.17 |

| Response (CRi/CRp vs. CR) | 1.28 (0.39, 4.19) | 0.68 |

| MRD at 3-7 Months | 50.38 (9.18, 276.63) | <0.0001 |

|

| ||

| At Completion of Therapy (≥ 8 Months from Therapy Initiation) (N=69)* | ||

|

| ||

| Age | 1.00 (0.96, 1.05) | 0.91 |

| Cyto (Fav vs. others) | 0.98 (0.27, 3.62) | 0.98 |

| MRD at ≥ 8 Months | 12.98 (3.82, 44.12) | <0.0001 |

The effect of response cannot be estimated because among the 65 evaluable patients, only 1 patient had CRp, the remaining 64 patients all had CR.

Table 1. Patient characteristics.

| Parameter | Overall cohort with CR/CRI N=280 (%) | Study cohort with MRD data N=186 (%) | CR/CRi without MRD data N=94 (%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age in years [Range] | 51 [17 – 79] | 51 [17 - 77] | 53 [19 - 79] | 0.08 |

| Age ≥ 65 | 18 (6) | 6 (3) | 12 (13) | |

|

| ||||

| Cytogenetics | ||||

| Favorable | 96 (34) | 34 (18) | 62 (66) | <0.0001 |

| Intermediate | 137 (49) | 115 (62) | 22 (23) | |

| Adverse | 36 (13) | 27 (15) | 9 (10) | |

| NA | 11 (4) | 10 (5) | 1 (1) | |

|

| ||||

| Median WBC × 109/L [Range] | 7.0 [0.5 – 103] | 4.7 [0.5 – 103] | 9.3 [0.6 – 97] | 0.01 |

|

| ||||

| Treatment regimen | ||||

| CIA | 120 (43) | 102 (55) | 18 (19) | <0.0001 |

| FIA | 43 (15) | 34 (18) | 9 (10) | |

| FLAG-Ida | 95 (34) | 34 (18) | 61 (65) | |

| CLIA | 22 (8) | 16 (9) | 6 (6) | |

|

| ||||

| Courses to CR/CRp/Cri | 0.91 | |||

| 1 | 263 (94) | 174 (94) | 89 (95) | |

| >1 | 17 (6) | 12 (6) | 5 (5) | |

|

| ||||

| Response | 0.63 | |||

| CR | 259 (93) | 174 (94) | 85 (90) | |

| CRp | 19 (7) | 11 (6) | 8 (8) | |

| CRi | 2 (<1) | 1 (<1) | 1 (1) | |

Discussion

Despite significant progress in the treatment of patients with acute leukemia, the majority of patients relapse.24 Although a subset of relapsed patients can be rescued with allogeneic stem cell transplant, the vast majority are resistant to their salvage treatments and succumb to their disease.25 Therefore, new agents with different mechanisms of action which can overcome this resistance to cytotoxic chemotherapy are needed. Clearly, however, the best strategy to manage relapse is to prevent it.

Assessment of minimal residual leukemia persisting after initial therapy has been of significant interest in pediatric patients with ALL (and more recently in adult ALL and AML), although defining the most reliable assay for this purpose remains controversial, except in certain subgroups.12 The utility of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) based assays for MRD monitoring in acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) and core binding factor leukemias is well established and more recent reports have demonstrated the potential importance of MRD monitoring in patients with NPM1 mutated patients.26-30 There are fewer large studies examining the benefit of MRD monitoring by flow cytometry in adult AML and concerns regarding standardization and reproducibly of the assays remain.31-33 However, the available data suggests that MRD monitoring by any means, be it imperfect, can assist in identifying individuals who are destined to relapse. This is of increasing relevance and importance as the potential for the development of novel, less toxic and more effective agents against residual leukemia populations is ever more realistic.

Our data, in a relatively large population of younger patients with AML who received a more intensive induction and consolidation regimen and achieved a high CR rate, further demonstrates the significant value of MRD assessment in patients with AML. The more intensive regimens with higher doses of cytarabine used in induction and continued use of anthracyclines in consolidation, is close to the limit of tolerance of cytotoxic chemotherapy in this younger population akin to the very intensive regimens used in the pediatric trials. As such, persisting overt leukemia (primary refractory disease) and even persisting MRD after such therapy can be more closely attributed to the inherent biological resistance of the leukemic cells rather than the inadequacy of therapy and clearly selects patients who are no longer benefiting from the cytotoxics.34 We have previously reported that patients who fail to achieve morphological remission after one course of such intensive induction regimens have a dismal prognosis and very few can be salvaged with an allogeneic stem cell transplant.35 The data from this report suggests that this observation can be taken a step further, identifying the patients more likely to relapse after achieving CR and prevent relapse by selecting novel therapeutic strategies to eradicate MRD followed by an allogeneic stem cell transplant.

In pediatric leukemia, where the population is more tolerant of cytotoxic agents, MRD assays have been successfully used to select patients for dose intensification.10, 11 Although in the adult population, one can consider persistent MRD as an indication for an allogeneic stem cell transplantation, recent data reporting that detectable MRD prior to an allogeneic stem cell transplant is a reliable predictor of failure, suggests that this strategy may not be the best in dealing with persistent MRD after induction and consolidation.36, 37 Alternative strategies such as monoclonal antibody based therapies including antibody-drug-conjugates and T-cell engaging antibodies, as well as in specific cases, use of appropriate small molecule inhibitors such IDH or FLT3 kinase inhibitors may provide us with more effective and less toxic ways to eradicate MRD. Currently, and based on precedent, allogeneic stem cell transplantation remains the only time-tested, immunologically driven tool to produce long-term cures in less favorable subsets of AML and in relapsed disease. However, with more sensitive and validated assays for MRD and using novel therapeutic strategies including combinations of antibodies and small molecule inhibitors, one can predict that more and more patients can achieve long term cure without the need for an allogeneic stem cell transplant, as has been the case for patients with APL where sensitive MRD monitoring and availability of effective targeted agents has rendered transplant unnecessary except for select few relapsed patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by the MD Anderson Cancer Center Support Grant CA016672,P30 CA016672

Footnotes

This study was presented in abstract form at the 57th annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, Orlando, FL, December 2015.

Authorship: Contribution: F.R., J.J. and H.K. designed and conducted the study. F.R. and J.J. wrote the manuscript. F.R., G.B., E.J., T.K., J.C. and H.K. designed the clinical trials. F.R., G.B., E.J., T.K., N.D., C.D., M.A., M.K., Z.E., G.G.M, J.C. and H.K. treated patients, S.P. and M.B. collected and analyzed the data. J.J., S.W., S.K. performed the flow analyses. X.W. and X.H. conducted the statistical analyses.

All authors declare no relevant conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Dohner H, Weisdorf DJ, Bloomfield CD. Acute Myeloid Leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1136–1152. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1406184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grimwade D, Hills RK, Moorman AV, et al. Refinement of cytogenetic classification in acute myeloid leukemia: determination of prognostic significance of rare recurring chromosomal abnormalities among 5876 younger adult patients treated in the United Kingdom Medical Research Council trials. Blood. 2010;116:354–365. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-254441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patel JP, Gonen M, Figueroa ME, et al. Prognostic relevance of integrated genetic profiling in acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1079–1089. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1112304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dohner H, Estey EH, Amadori S, et al. Diagnosis and management of acute myeloid leukemia in adults: recommendations from an international expert panel, on behalf of the European LeukemiaNet. Blood. 2010;115:453–474. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-235358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walter RB, Kantarjian HM, Huang X, et al. Effect of complete remission and responses less than complete remission on survival in acute myeloid leukemia: a combined Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, Southwest Oncology Group, and M. D. Anderson Cancer Center Study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1766–1771. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kern W, Haferlach T, Schoch C, et al. Early blast clearance by remission induction therapy is a major independent prognostic factor for both achievement of complete remission and long-term outcome in acute myeloid leukemia: data from the German AML Cooperative Group (AMLCG) 1992 Trial. Blood. 2003;101:64–70. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-02-0532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arellano M, Pakkala S, Langston A, et al. Early clearance of peripheral blood blasts predicts response to induction chemotherapy in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer. 2012;118:5278–5282. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gajjar A, Ribeiro R, Hancock ML, et al. Persistence of circulating blasts after 1 week of multiagent chemotherapy confers a poor prognosis in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 1995;86:1292–1295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nachman JB, Sather HN, Sensel MG, et al. Augmented post-induction therapy for children with high-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia and a slow response to initial therapy. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1663–1671. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199806043382304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pui CH, Pei D, Coustan-Smith E, et al. Clinical utility of sequential minimal residual disease measurements in the context of risk-based therapy in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: a prospective study. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:465–474. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70082-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rubnitz JE, Inaba H, Dahl G, et al. Minimal residual disease-directed therapy for childhood acute myeloid leukaemia: results of the AML02 multicentre trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:543–552. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70090-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grimwade D, Freeman SD. Defining minimal residual disease in acute myeloid leukemia: which platforms are ready for “prime time”? Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2014;2014:222–233. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2014.1.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ravandi F, Jorgensen JL. Monitoring minimal residual disease in acute myeloid leukemia: ready for prime time? J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2012;10:1029–1036. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2012.0105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paietta E. Minimal residual disease in acute myeloid leukemia: coming of age. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2012;2012:35–42. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2012.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hourigan CS, Karp JE. Minimal residual disease in acute myeloid leukaemia. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2013;10:460–471. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2013.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheson BD, Bennett JM, Kopecky KJ, et al. Revised recommendations of the International Working Group for Diagnosis, Standardization of Response Criteria, Treatment Outcomes, and Reporting Standards for Therapeutic Trials in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4642–4649. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Estey EH, Thall PF, Pierce S, et al. Randomized phase II study of fludarabine + cytosine arabinoside + idarubicin +/- all-trans retinoic acid +/- granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in poor prognosis newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome. Blood. 1999;93:2478–2484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nazha A, Kantarjian H, Ravandi F, et al. Clofarabine, idarubicin, and cytarabine (CIA) as frontline therapy for patients </=60 years with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia. Am J Hematol. 2013;88:961–966. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jaso JM, Wang SA, Jorgensen JL, Lin P. Multi-color flow cytometric immunophenotyping for detection of minimal residual disease in AML: past, present and future. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2014;49:1129–1138. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2014.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ouyang J, Goswami M, Tang G, et al. The clinical significance of negative flow cytometry immunophenotypic results in a morphologically scored positive bone marrow in patients following treatment for acute myeloid leukemia. Am J Hematol. 2015;90:504–510. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric-Estimation from Incomplete Observations. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cox DR. Regression Models and Life-Tables. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B-Statistical Methodology. 1972;34:187. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gooley TA, Leisenring W, Crowley J, Storer BE. Estimation of failure probabilities in the presence of competing risks: new representations of old estimators. Stat Med. 1999;18:695–706. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19990330)18:6<695::aid-sim60>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ravandi F. Relapsed acute myeloid leukemia: why is there no standard of care? Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2013;26:253–259. doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2013.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Breems DA, Van Putten WL, Huijgens PC, et al. Prognostic index for adult patients with acute myeloid leukemia in first relapse. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:1969–1978. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grimwade D, Jovanovic JV, Hills RK, et al. Prospective minimal residual disease monitoring to predict relapse of acute promyelocytic leukemia and to direct pre-emptive arsenic trioxide therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3650–3658. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yin JA, O'Brien MA, Hills RK, Daly SB, Wheatley K, Burnett AK. Minimal residual disease monitoring by quantitative RT-PCR in core binding factor AML allows risk stratification and predicts relapse: results of the United Kingdom MRC AML-15 trial. Blood. 2012;120:2826–2835. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-06-435669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ivey A, Hills RK, Simpson MA, et al. Assessment of Minimal Residual Disease in Standard-Risk AML. N Engl J Med. 2016 doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1603847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhu HH, Zhang XH, Qin YZ, et al. MRD-directed risk stratification treatment may improve outcomes of t(8;21) AML in the first complete remission: results from the AML05 multicenter trial. Blood. 2013;121:4056–4062. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-11-468348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kronke J, Schlenk RF, Jensen KO, et al. Monitoring of minimal residual disease in NPM1-mutated acute myeloid leukemia: a study from the German-Austrian acute myeloid leukemia study group. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2709–2716. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.0371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Freeman SD, Virgo P, Couzens S, et al. Prognostic relevance of treatment response measured by flow cytometric residual disease detection in older patients with acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:4123–4131. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Terwijn M, van Putten WL, Kelder A, et al. High prognostic impact of flow cytometric minimal residual disease detection in acute myeloid leukemia: data from the HOVON/SAKK AML 42A study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3889–3897. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.9628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walter RB, Gooley TA, Wood BL, et al. Impact of pretransplantation minimal residual disease, as detected by multiparametric flow cytometry, on outcome of myeloablative hematopoietic cell transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1190–1197. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.8121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ravandi F. Primary refractory acute myeloid leukaemia - in search of better definitions and therapies. Br J Haematol. 2011;155:413–419. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08869.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ravandi F, Cortes J, Faderl S, et al. Characteristics and outcome of patients with acute myeloid leukemia refractory to 1 cycle of high-dose cytarabine-based induction chemotherapy. Blood. 2010;116:5818–5823. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-07-296392. quiz 6153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Araki D, Wood BL, Othus M, et al. Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation for Acute Myeloid Leukemia: Time to Move Toward a Minimal Residual Disease-Based Definition of Complete Remission? J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:329–336. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.3826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Walter RB, Buckley SA, Pagel JM, et al. Significance of minimal residual disease before myeloablative allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for AML in first and second complete remission. Blood. 2013;122:1813–1821. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-06-506725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.