Abstract

OBJECTIVES

Hospitalization is associated with subsequent decrements in health regardless of admitting diagnosis. Little is known, however, about the impact of readmission on functional recovery following surgery. Our objective was to examine the impact of readmission on functional recovery after elective surgery in older persons.

DESIGN

Prospective cohort of elective surgery patients aged 70 and older, enrolled from June 2010 to August 2013.

SETTING

Two academic medical centers

PARTICIPANTS

Community-dwelling older adults (N=566) with mean (standard deviation) age 77 (5) years undergoing major elective surgery, and expected to be admitted for at least 3 days.

MEASUREMENTS

Readmission was assessed at multiple interviews with patients and family members over 18 months, and was validated against medical record review. Physical function was assessed using Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL), Activities of Daily Living (ADL), the SF-12 Physical Component Summary (PCS), and a standardized functional composite.

RESULTS

Two hundred-fifty five (45%) participants experienced 503 readmissions. Readmissions were associated with delays in functional recovery, across all measures of physical function. The occurrence of two or more readmissions over 18 months was associated with persistent and significantly increased risk of IADL dependence, with relative risk (RR) = 1.8 and 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.5 to 2.3, and ADL dependence (RR = 3.3; 95% CI = 1.7 to 6.4). The degree of functional impairment increased progressively with the number of readmissions. Readmissions within 2 months resulted in delayed functional recovery to baseline by 18 months, whereas readmissions between 12 and 18 months resulted in a loss of functional recovery previously achieved.

CONCLUSIONS

Readmission following elective surgery may contribute to delays in functional recovery and persistent functional deficits, among older adults.

Keywords: Physical function, readmission, surgery, cohort study, aging

Introduction

Functional impairments are major contributors to disability, loss of independence, diminished quality of life, and increased mortality in older persons.1–3, 4 Recovery of physical function is an important goal of elective orthopedic or vascular surgeries, and a critical expectation on the part of patients undergoing such procedures.5, 6 Factors that may interrupt the recovery process following surgery therefore assume paramount relevance for clinicians, patients, and their family members.

Hospitalization has been increasingly recognized as a pivotal event in the life of an older person,7 predictive of accelerated functional and cognitive decline8–10 and associated with the development of disability.11, 12 Moreover, hospital readmission may be associated with delays in functional recovery following surgery.13 While 30-day readmission is typically monitored to identify complications related to the surgical procedure,14 readmissions following orthopedic or vascular procedures may exhibit diverse etiology beyond surgical complications,15 and there may be differences in the causes of ‘early’ vs. ‘late’ readmissions.16 Although readmission has been associated with diminished physical capacity for at least six months following surgery,13 the effect of recurrent admissions over longer periods of time has not been previously examined.

Thus, we investigated whether the number and timing of readmissions was associated with functional recovery over a period of 18 months following a major elective surgical procedure in older persons. Since most of the surgeries were being done to improve functioning, we anticipated that most participants would recover physical function to a level at or above their preoperative baseline, in the absence of readmission. We hypothesized that readmission would be associated with acute disruption of recovery, and that repeated readmissions would have more lasting adverse effects.

Methods

Study Population

We conducted a longitudinal analysis of data from the Successful Aging after Elective Surgery (SAGES),17 an ongoing prospective cohort study of older adults undergoing major scheduled non-cardiac surgery. The study design and methods have been described in detail previously.17, 18 In brief, eligible participants were age 70 years and older, English speaking, scheduled to undergo elective surgery at two Harvard-affiliated academic medical centers and with an anticipated length of stay of at least 3 days. Eligible surgical procedures were: total hip or knee replacement, lumbar, cervical, or sacral laminectomy, lower extremity arterial bypass surgery, open abdominal aortic aneurysm repair, and open or laparoscopic colectomy. Exclusion criteria included evidence of dementia, delirium, hospitalization within 3 months, terminal condition, legal blindness, severe deafness, history of schizophrenia or psychosis, and history of alcohol abuse or withdrawal. A total of 566 patients met all eligibility criteria and were enrolled between June 18, 2010 and August 8, 2013. Written informed consent for study participation was obtained from all participants according to procedures approved by the institutional review boards of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, the two study hospitals, and Hebrew SeniorLife, the study coordinating center, all located in Boston, Massachusetts.

Data collection

All participants underwent a structured home-based assessment and medical record review two to four weeks prior to surgery (‘baseline’ assessment). Participants underwent additional in-person assessments at one month, two months, six months, 12 months and 18 months post-surgery; these were supplemented by telephone interviews conducted at four, nine, and 15 months. Deaths were reported by informants or determined from review of medical records or obituaries. A total of 12 (2.1%) participants died during the study period; these participants had a median follow-up of 6 months. An additional 21 (3.7%) participants withdrew prior to 18 months post-surgery; these participants had a median follow-up of 4 months. For the remaining 533 participants, data were available for 4789 (97%) of 4950 scheduled interviews. Interviews were conducted by trained research associates. An experienced study physician conducted all chart reviews.

Surgical Procedures

The majority of participants (460 [81%] underwent orthopedic procedures, while 71 (13%) and 35 (6%) had general and vascular surgeries, respectively. Participants underwent 116 (21%) total hip replacements, 209 (37%) total knee replacements, 113 (20%) lumbar laminectomies, 22(4%) cervical laminectomies, 23 (4%) lower-extremity bypasses, 12 (2%) open abdominal aortic aneurysm repairs, 32 (6%) open colectomies, and 39 (7%) laparoscopic colectomies.

Assessment of physical function

Assessments of physical function included self-reported ability to perform activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), as well as the 12-item Medical Outcomes Study Short Form (SF-12) Physical Component Summary (PCS).19–21 IADL and ADL data were collected at all visits, while the PCS was obtained at in-person visits only. Measurement of ADL assessed the ability to independently bathe, groom, dress, feed, transfer from a bed to a chair, use the toilet, and walk across a small room. IADL included the ability to independently use the telephone, travel to places outside of walking distance, shop for groceries, prepare food, perform household chores, manage medications, and manage money. For the present analyses, participants were considered ADL or IADL independent if they reported full ability to perform each task included within the relevant assessment (i.e., in the case of IADL, the fully independent ability to perform each of the seven instrumental activities). Total or partial inability to perform any of the relevant tasks was considered as evidence of ADL or IADL dependence.

In addition to these measures, SAGES investigators constructed a validated composite measure of physical function capturing information in IADL, ADL and PCS. The composite was created to provide a continuous measure to more fully capture the complete spectrum of physical functioning and to minimize potential floor and ceiling effects. This measure was calibrated to normative data from the National Institutes of Health’s Patient Reported Outcomes Measure Information System (PROMIS) sample;22, 23 as described previously.24 The SAGES composite demonstrated predictive criterion validity, with scores indicating less impairment demonstrated to be associated with shorter length of hospital stay and lower risk of discharge to a rehabilitation facility.24 The mean SAGES functional composite, proportion of individuals reporting IADL independence and ADL dependence, and mean PCS were considered separately in parallel analyses.

Assessment of hospital readmission

The primary independent variable was readmission, defined as a post-surgery hospital readmission with a length of stay of at least one night. During each follow-up interview, participants were asked about any readmissions occurring since their prior interviews. The reliability of these reports was verified with medical record review in a subsample of 208 participants. Proportionate agreement between patient reports and medical record reviews on the total count of admissions was 90%, kappa = 0.79 (95% Confidence Interval: 0.71 to 0.87); and agreement on admission month and year was 99% (kappa=0.78, 95% CI, 0.72–0.85).). A clinical consensus panel of 3 expert clinicians reviewed the abstracted medical information and adjudicated whether the readmission was directly related to the index surgical event, such as a surgical complication or sequelae of the hospitalization.

Measurement of covariates

Sex, racial and ethnic identification, years of education, marital status, height, and weight were obtained from baseline interviews. Age, surgery type, and baseline comorbidities were determined from chart review. The Charlson comorbidity index25 (CCI) was created based on the chart review and was used to quantify the cumulative burden of comorbidity.

Statistical analysis

The association between readmission and each functional outcome was estimated using mixed effect regression models. Participant-specific intercepts were estimated as random effects to account for serial correlation between repeated measurements on participants. All models adjusted for participants’ baseline age, sex, race/ethnicity, years of education, body mass index, Charlson comorbidity index, and surgery type. Covariates were considered fixed over the duration of enrollment. A linear model was used to estimate the mean change in the SF-12 PCS and in the SAGES functional composite. A robust ‘modified’ Poisson regression model26, 27 was used to estimate the relative risk (RR) for ADL and IADL dependence at each assessment time-point. All point estimates were accompanied by 95% confidence intervals (CI). Model fit was assessed using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC).28

Estimation of readmission effects

Models were parameterized to assess both the short-term and persistent effects of readmission. At each visit, an indicator variable (yes/no) specifying whether a hospitalization had occurred at any point after the prior visit was included as an independent variable; the estimated effect associated with this variable was interpreted as the acute effect of readmission on outcomes. Additionally, the count of additional readmissions to date was included; the corresponding effect was interpreted as quantifying the cumulative, longer-term effect of multiple readmissions. An initial set of models estimated these acute and longer-term effects separately, while a second (definitive) model estimated both at once, taking into account their relative contributions to changes in function. Consistent with the observed pattern of functional recovery (see Results), regression models were parameterized to allow for nonlinear trends at one and two months, and a linear trend thereafter. Due to the limited number of individuals with three or more readmissions, the time-dependent cumulative readmission variable was analyzed as a three-level step function: 0, 1, ≥ 2 readmissions. Sensitivity analyses included re-estimation of effects restricted only to those readmissions which were deemed unrelated to the index surgical event by the clinical consensus expert panel, and also to the subset of individuals who received orthopedic procedures. An additional sensitivity assessment controlled for baseline outcome levels in functional variables in order to determine whether results were robust to baseline differences between those who were had readmission and those who did not. Significance testing for all analyses was based on a two-sided type-I error probability (alpha) of 0.05. Analyses were conducted using Stata MP version 13.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) and R version 3.1.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Baseline cohort characteristics (N=566) are presented in Table 1. The mean (SD) age of the patients was 76.7 (5.2) years, and fifty-eight percent of participants were female. The mean (SD) Charlson Comorbidity Index was 1.0 (1.3), and approximately one third of participants had CCI of 2 or greater. A total of 460 (81%) participants underwent orthopedic surgical interventions, while 35 (6%) underwent vascular surgeries and 71 (13%) colectomies.

Table 1.

Description of study cohort (N=566), mean (SD) or count (percent)

| Demographics, Health History, and Physical & Cognitive Functioning | ||

| Age, mean years (SD) | 76.7 | (5.2) |

| Female sex, % | 330 | (58) |

| BMI, kilograms/meter-squared, mean (SD) | 29 | (6) |

| Race, % | ||

| Asian | 5 | (< 1) |

| Black | 29 | (5) |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 1 | (< 1) |

| White | 528 | (93) |

| More than one race | 3 | (< 1) |

| Hispanic Ethnicity, % | 7 | (1) |

| Married, % | 335 | (59) |

| Education, years | 15.0 | (2.9) |

| Cardiovascular Disease, % | 124 | (22) |

| Diabetes, % | 115 | (20) |

| Cancer, % | 75 | (13) |

| Peripheral Vascular Disease, % | 67 | (12) |

| Cerebrovascular Disease, % | 51 | (9) |

| Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, % | 36 | (6) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 1.0 | (1.3) |

| CCI ≥ 2, % | 167 | (30) |

| Cognitive Functioning (3MS), mean (SD) | 93.4 | (5.4) |

| 3MS < 85, % | 39 | (7) |

| Physical Functioning and Independence | ||

| MOS SF-12 Physical Component Summary, mean (SD) | 35 | (10) |

| ADL; One or more dependencies, % | 42 | (7) |

| IADL; One or more dependencies, % | 157 | (28) |

| Type of Surgery, % | ||

| Orthopedic | 460 | (81) |

| Vascular | 35 | (6) |

| Gastrointestinal | 71 | (13) |

SD – standard deviation; BMI – body mass index; CCI – Charlson Comorbidity Index; 3MS – Modified Mini-Mental State Examination; MOS SF-12 – Medical Outcomes Study Short Form-12; ADL – Activities of Daily Living; IADL – Instrumental Activities of Daily Living

Readmission experience

255 participants (45%) had 503 readmissions: 143 individuals had exactly one, and 112 had two or more, with a maximum of 12. Seventy (12%) participants were readmitted within one month of the index surgery. A total of 203 (36%) participants reported 345 readmissions deemed unrelated to the index hospitalization by the expert panel. Among these individuals, 133 participants had exactly one unrelated readmission, and 70 had two or more, with a maximum of 9.

Functional recovery following surgery

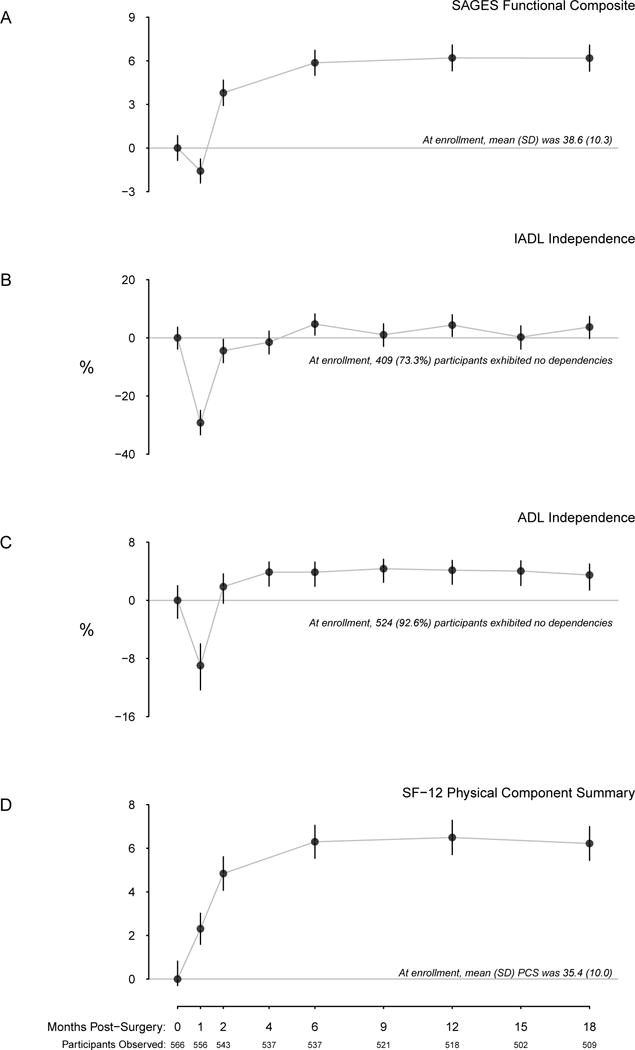

Figure 1 depicts the trend in each measure of physical functioning. At baseline, the mean (standard deviation) functional composite was 39 (10); participants experienced decline in this measure at one month, but then recovery to approximately 45 points at six months and thereafter. The baseline proportion of participants who were IADL independent was 72% (95% CI: 68 to 76%). Thirty days after discharge, the proportion who were independent in IADL fell to 43% (95% CI: 39 to 47%). The proportion who were independent recovered at 60 days, with 68% (95% CI: 64 to 72%) independent. Subsequently, this value remained stable to 18 months, where 76% (95% CI 72 to 80%) of the cohort was IADL independent. The trend in ADL followed a similar pattern to IADL, although as expected the proportion of individuals who were ADL independent was greater than the proportion who were IADL independent at all time points. The mean PCS score was 35.4 (95% CI 34.5 to 36.2) at baseline and increased to 37.7 (95% CI: 36.9 to 38.4) one month after surgery. From two to 18 months, this mean was relatively stable.

Figure 1.

Change from baseline functional recovery with time, to 18 months. Change in the SAGES functional composite is given in panel A, with horizontal gray line corresponding to zero change. The proportions of individuals exhibiting no IADL or ADL dependencies are depicted in panels B and C, respectively, with the zero line corresponding to no change from baseline. Mean change in SF-12 PCS is depicted in panel D.

The collective pattern of decreases in physical functioning at one month, followed by recovery at two months, and a stable trend thereafter was common to the SAGES physical composite, IADL, and ADL measures.

Acute effect of readmission on functional recovery

Table 2 shows the risk for IADL and ADL dependence along with differences in SF-12 and physical functioning composite scores associated with readmission. There was a statistically significant association of readmission with the SAGES functional composite; participants reporting readmission experienced less recovery at the next study visit with a mean (95% CI) difference of −1.4 (95% CI = −2.5 to −0.02) compared with those without readmission. There was evidence of an association between readmission and IADL dependence; in models considering acute and longer-term effects together, participants were on average 10% more likely (relative risk, RR = 1.2; 95% CI = 0.99 to 1.4) to have dependency in IADL when the assessment was preceded by a readmission. Similar associations with ADL were observed (RR = 1.3; 95% CI = 0.9 to 2.0). Results were similar for PCS.

Table 2.

Longitudinal analysis of association of recent readmission and cumulative readmissions with changes in physical functioning (N=566) to 18 months post-hospitalization.

| aAcute and Longer-term Associations Estimated Separately | bAcute and Longer-term Associations Estimated Simultaneously | |

|---|---|---|

| SAGES Physical Function Composite | Mean Difference (95% CI) |

Mean Difference (95% CI) |

| Hospitalized since last study visit | −2.8 (−3.8, −1.8) |

−1.4 (−2.5, −0.2) |

| Cumulative readmissions to date | ||

| 0 | Referent | Referent |

| 1 | −2.1 (−3.2, −1.004) |

−1.5 (−2.6, −0.4) |

| 2+ | −4.7 (−6.2, −3.3) |

−4.0 (−5.6, −2.4) |

|

| ||

| Instrumental Activities of Daily Living; one or more dependencies |

cRelative Risk (95% CI) |

Relative Risk (95% CI) |

| dHospitalized since last study visit | 1.5 (1.4, 1.7) |

1.2 (0.99, 1.4) |

| Cumulative readmissions to date | ||

| 0 | Referent | Referent |

| 1 | 1.5 (1.3, 1.8) |

1.4 (1.2, 1.7) |

| 2+ | 2.0 (1.7, 2.5) |

1.8 (1.5, 2.3) |

|

| ||

| Activities of Daily Living; one or more dependencies | Relative Risk (95%CI) |

Relative Risk (95%CI) |

| Hospitalized since last study visit | 2.1 (1.4, 3.0) |

1.3 (0.9, 2.0) |

| Cumulative readmissions to date | ||

| 0 | Referent | Referent |

| 1 | 1.9 (1.3, 2.8) |

1.6 (1.0, 2.5) |

| 2+ | 4.1 (2.3, 7.2) |

3.3 (1.7, 6.4) |

|

| ||

| MOS SF-12 Physical Component Summary | Mean Difference (95% CI) |

Mean Difference (95% CI) |

| Hospitalized since last study visit | −2.3 (−3.2, −1.4) |

−1.5 (−2.6, −0.4) |

| Cumulative readmissions to date | ||

| 0 | Referent | Referent |

| 1 | −1.2 (−2.2, −0.3) |

−0.7 (−1.7, 0.4) |

| 2+ | −3.3 (−4.6, −1.9) |

−2.4 (−4.0, −0.9) |

Analyses based on 503 hospital readmissions. MOS SF-12 – Medical Outcomes Study Short Form-12; CI – Confidence Interval. Models adjust for participants’ baseline age, sex, race/ethnicity, years of education, body mass index, Charlson comorbidity index, and surgery type. The time trend is allowed to vary freely in a nonlinear fashion from baseline through the 1 and 2 month visits, and assumed to follow a linear course thereafter, consistent with exploratory analyses (Figure 1).

Recent hospitalization and cumulative history of hospitalization considered in separate models

Recent hospitalization and cumulative history of hospitalization considered in one combined model (i.e. controlling for one another)

Multiplicative increase in the probability of ADL or IADL dependency vis-à-vis referent category

Referent: no hospitalization at current visit

Longer-term and cumulative effect of readmission on functional recovery

The cumulative influence of readmissions was considerable. One or more readmissions was associated with substantial and significant decreases in the functional composite; the presence of two or more readmissions was associated with a −4.0 point decrease in the composite index (95% CI = −5.6 to −2.4) compared to absence of any readmissions (Table 2). Two or more readmissions were associated with an estimated RR for IADL dependence of 1.8 (95% CI = 1.5 to 2.3) at any time following the second readmission. Results followed a consistent pattern for ADL and PCS.

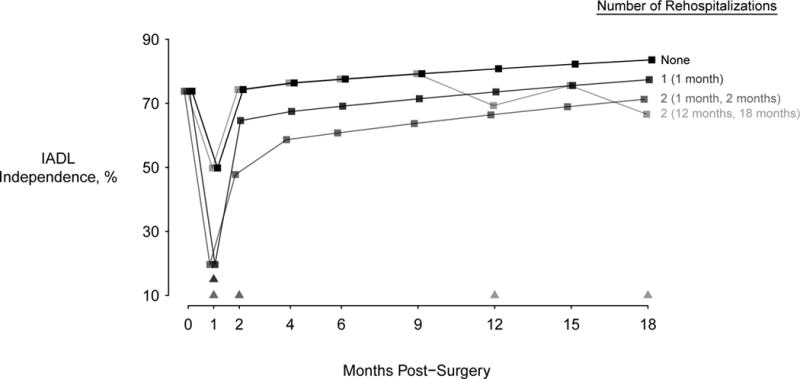

Figure 2 illustrates the estimated course of functional recovery and effects of readmission for typical study participants with four different modeled readmission experiences post-surgery. Here we observe the model-based estimated mean probability of IADL independence as a function of time for individuals with no readmissions, one or two early readmissions (e.g., within two months post-surgery), and two readmissions during the period between the 12 and 18 months assessments. The earlier readmissions (prior to two months) are associated with clinically meaningful differences in the probability of IADL independence that persists to 18 months, as indicated by the parallel model-based mean estimates shown for individuals with either no readmissions or with readmissions occurring only prior to two months. By contrast, readmissions occurring later (as represented by the fourth plotted line, in light grey) appear to be associated with a falling away from the pattern of functional recovery shown with the other trajectories, such that at 18 months the pattern is one of increasing functional dependence.

Figure 2.

Model-estimated probability of IADL independence as a function of time for an individual matching typical SAGES demographic and health history profile, under four different hypothetical hospitalization experiences. Dark black symbols and lines describe the trajectory associated with no readmissions, while other lines depict various patterns of readmission over 18 months. Visits at which hospitalizations are recorded are demarcated by triangles with the same shading as the corresponding trajectories.

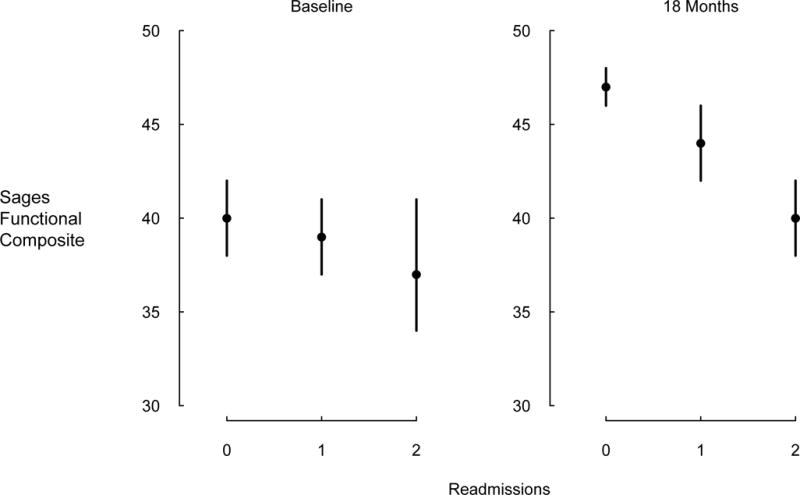

Figure 3 shows the mean of the SAGES functional composite at baseline and at 18 months stratified by the cumulative hospitalization count for individuals completing the 18-month interview. At baseline, mean differences in the SAGES functional composite between groups fated not to be readmitted, to be readmitted once, or to be readmitted more than once were statistically nonsignificant. By 18 months, these groups had differentiated themselves such that those with two or more readmissions had a mean functional composite seven points lower than those who were never readmitted. Results were similar for the other measures of physical function. The proportion independent in IADL at 18-months was 83% (95% CI = 79 to 87%) of participants never readmitted, 72% (95% CI = 64 to 80%) of participants readmitted once, and 60% (95% CI = 50% to 87%) of participants readmitted more than once. Results were similar for the other functional outcome measures.

Figure 3.

SAGES functional composite at baseline and 18 months follow-up, among individuals who have 18 months’ data, stratified by number of readmissions experienced to 18 months. Means and 95% confidence intervals are shown. Differences at baseline are modest and statistically nonsignificant, but are greater at 18 months.

Sensitivity Analyses

When models were restricted to the 345 readmissions deemed to be unrelated to the index surgical events by clinical adjudication, results were essentially identical to those including all readmissions (shown in Table 2). Likewise, when attention was restricted to participants undergoing orthopedic procedures (N = 460), results were unchanged. Finally, control for baseline outcomes demonstrated no significant changes to the results.

Discussion

Hospital readmission is a known risk factor for deleterious outcomes among older men and women,7–11, 13 but the degree to which it can influence functional recovery following surgery has not been previously well-examined. In this prospective cohort study of 566 older adults undergoing major elective surgery, we found that readmissions over an 18-month period were associated with both acute and more long-lasting delays in functional recovery, across multiple measures of physical function, including the functional composite measure, IADL, ADL, and SF-12 PCS. While the influence of a single readmission on PCS appeared to be diminished over time, the cumulative influence of multiple (two or more) readmissions was pronounced and durable on IADL and all other functional outcomes examined. Thus, an exposure – response effect was demonstrated, with the degree of functional impairment increasing progressively with the number of readmissions.

The timing of the readmissions impacted on the pattern of functional recovery. Early readmissions, occurring within the first 2 months, resulted in a delayed functional recovery which did not achieve baseline by 18 months in most cases. Late readmissions, between 12 and 18 months resulted in a loss of functional recovery previously achieved, and progressive functional decline.

Previous studies of elective orthopedic surgery suggest a 5% to 10% readmission rate at 30 days.29, 30 Our one-month readmission rate was comparable at 12%. Over an 18-month period, our one-time readmission rate in this group of older elective surgery patients was 45%. Our study extends the previous work by examining the number and timing of readmissions following surgery over an extended time period.

In a sensitivity analysis, we restricted analyses to readmissions that were not related to the index hospitalization, in order to separate out the effects of the initial surgery and its potential complications. The results were unchanged, suggesting that readmission effects are similar whether or not they were related to the index surgery and hospitalization. Since the causes of the readmissions were heterogeneous,13–16 this finding underscores the importance of understanding both the precipitating factors for readmission and the aspects of readmission itself that may act to impair the independence of older adults post-surgery.

How do readmissions contribute to impaired recovery? In addition to the acute illness that precipitated the readmission, the hospital stay itself may contribute to functional decline through myriad factors. Previous studies have well-documented the many hazards of hospitalization for older persons,7, 31, 32 including factors such as delirium, immobilization, deconditioning, sleep deprivation, malnutrition, dehydration, polypharmacy, indwelling bladder catheters, complications of diagnostic or therapeutic procedures, and psychological stress. These factors occur commonly in older hospitalized patients, and undoubtedly contribute to the observed functional decline.

The strengths of this study include the prospective design and large sample size with nearly complete data and minimal attrition, due to rigorous study procedures detailed previously.18 The frequency of assessments allowed for analyses that linked changes in physical functioning relative to date of readmission. Accuracy of the self-report information for readmissions was validated against medical record review. Covariate adjustment, sensitivity analyses, and the consistency of findings across four measures of physical function further support the validity of our findings. The finding of an exposure-response relationship between readmissions and functional impairment underscores the robustness of our findings.

Several limitations must also be acknowledged. First, our ability to assess causality is limited in this observational study. We have endeavored to address this limitation via our analyses of the temporal relation of events to changes in physical function as well as stratification by cumulative number of readmissions (Figure 3). Second, while representative of the diversity in the greater Boston area, our sample was demographically homogenous: predominantly white, well-educated, and recruited from two academic medical centers in a single geographic region. We expect that these factors do not compromise the validity of our findings; however, generalizability to broader populations must be confirmed in future studies. Finally, given the relatively small numbers of participants receiving many specific procedures, we were unable to robustly assess the influence of specific surgical types on our results, though we did observe that limiting the sample to orthopedic surgery alone did not produce qualitative changes in our conclusions.

These results add to the growing body of literature suggesting that hospital readmission is associated with downstream decrements in heath status independent of the reason for the index hospitalization.7, 33 They suggest that better understanding of the causes of early readmission in elective surgical patients may inform interventions that enhance the benefits of surgery over the longer term. They also provide evidence for the value of wider adoption of interventions to reduce the functional impact of readmission such as the Hospital Elder Life Program (HELP)34–36 and other strategies aimed at preventing unanticipated readmissions.37–39

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was funded by P01AG031720 and K07AG041835 from the National Institute on Aging (SKI). Dr. Marcantonio’s effort was also supported in part by National Institute of Aging grants R01AG030618 and K24AG035075. Dr. Inouye holds the Milton and Shirley F. Levy Family Chair at Hebrew SeniorLife/Harvard Medical School.

Sponsor’s Role: This study was funded by grants P01AG031720 (SKI) and K07AG041835 (SKI) from the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Marcantonio was supported in part by grant K24AG035075 from the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Inouye holds the Milton and Shirley F. Levy Family Chair. The funding sources had no role in the design, conduct or reporting of this study.

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Alsop receives institutional royalties from GE Healthcare for patents related to the arterial spin labeling MRI technique used for this study. None of the other authors report any conflicts of interest. All other co-authors fully disclose they have no financial interests, activities, relationships and affiliations. The co-authors also declare they have no potential conflicts in the three years prior to submission of this manuscript.

| Elements of Financial/Personal Conflicts | Margaret A. Pisani | Asha Albuquerque | Edward R. Marcantonio | Richard N. Jones | ||||

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| Employment or Affiliation | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Grants/Funds | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Honoraria | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Speaker Forum | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Consultant | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Stocks | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Royalties | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Expert Testimony | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Board Member | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Patents | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Personal Relationship | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Elements of Financial/Personal Conflicts | Ray Yun Gou | Tamara G. Fong | Eva M. Schmitt | Douglas Tommet | ||||

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| Employment or Affiliation | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Grants/Funds | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Honoraria | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Speaker Forum | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Consultant | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Stocks | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Royalties | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Expert Testimony | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Board Member | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Patents | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Personal Relationship | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Grants/Funds | X | X | X | |||||

| Honoraria | X | X | X | |||||

| Speaker Forum | X | X | X | |||||

| Consultant | X | X | X | |||||

| Stocks | X | X | X | |||||

| Royalties | X | X | X | |||||

| Elements of Financial/Personal Conflicts | Illean I. Isaza Aizpurua | David C. Alsop | Sharon K. Inouye | Thomas G. Travison | ||||

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| Employment or Affiliation | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Grants/Funds | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Honoraria | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Speaker Forum | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Consultant | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Stocks | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Royalties | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Expert Testimony | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Board Member | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Patents | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Personal Relationship | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Grants/Funds | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Honoraria | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Speaker Forum | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Consultant | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Stocks | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Royalties | X | X | X | X | ||||

Footnotes

This work is dedicated to the memory of Joshua Bryan Inouye Helfand.

Authors’ roles: Drs. Marcantonio, Jones, Fong, Schmitt, Isaza, Alsop and Inouye participated in the design of SAGES and in its data acquisition. Drs. Inouye and Travison developed the concept for this manuscript. Drs. Pisani, Inouye, and Travison drafted the manuscript. Ms. Gou and Dr. Travison developed the data analyses and displays. All authors participated in interpretation of data, and provided critical review of, intellectual contributions to, and approval of the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Metter EJ, Schrager M, Ferrucci L, et al. Evaluation of movement speed and reaction time as predictors of all-cause mortality in men. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60:840–846. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.7.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hagger-Johnson G, Deary IJ, Davies CA, et al. Reaction time and mortality from the major causes of death: the NHANES-III study. PloS One. 2014;9:e82959. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Onder G, Penninx BWJH, Ferrucci L, et al. Measures of physical performance and risk for progressive and catastrophic disability: results from the Women’s Health and Aging Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60:74–79. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.1.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Groessl EJ, Kaplan RM, Rejeski WJ, et al. Health-related quality of life in older adults at risk for disability. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33:214–218. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zywiel MG, Mahomed A, Gandhi R, et al. Measuring expectations in orthopaedic surgery: a systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471:3446–3456. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-3013-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brinker MR, O’Connor DP. Stakeholders in outcome measures: review from a clinical perspective. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471:3426–3436. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-3265-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krumholz HM. Post-hospital syndrome–an acquired, transient condition of generalized risk. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:100–102. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1212324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gill TM, Allore HG, Gahbauer EA, et al. Change in disability after hospitalization or restricted activity in older persons. JAMA. 2010;304:1919–1928. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gill TM, Gahbauer EA, Han L, et al. Functional trajectories in older persons admitted to a nursing home with disability after an acute hospitalization. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:195–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02107.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ehlenbach WJ, Hough CL, Crane PK, et al. Association between acute care and critical illness hospitalization and cognitive function in older adults. JAMA. 2010;303:763–770. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gill TM, Allore HG, Holford TR, et al. Hospitalization, restricted activity, and the development of disability among older persons. JAMA. 2004;292:2115–2124. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.17.2115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gill TM, Allore HG, Gahbauer EA, et al. The role of intervening illnesses and injuries in prolonging the disabling process. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:447–452. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boockvar KS, Halm EA, Litke A, et al. Hospital readmissions after hospital discharge for hip fracture: surgical and nonsurgical causes and effect on outcomes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:399–403. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Merkow RP, Ju MH, Chung JW, et al. Underlying reasons associated with hospital readmission following surgery in the United States. JAMA. 2015;313:483–495. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.18614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maslow J, Hutzler L, Slover J, et al. Etiology of Readmissions Following Orthopaedic Procedures and Medical Admissions A Comparative Analysis. Bull Hosp Jt Dis. 2015;73:269–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Graham KL, Wilker EH, Howell MD, et al. Differences between early and late readmissions among patients: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:741–749. doi: 10.7326/AITC201506020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schmitt EM, Marcantonio ER, Alsop DC, et al. Novel Risk Markers and Long-Term Outcomes of Delirium: The Successful Aging after Elective Surgery (SAGES) Study Design and Methods. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13:818.e811–818.e810. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2012.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmitt EM, Saczynski JS, Kosar CM, et al. The Successful Aging After Elective Surgery Study: Cohort Description and Data Quality Procedures. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:2463–2471. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, et al. Studies of Illness in the Aged: The Index of ADL: A Standardized Measure of Biological and Psychosocial Function. JAMA. 1963;185:914–919. doi: 10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9:179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ware J, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Medical Care. 1996;34:220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cella D, Yount S, Rothrock N, et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS): progress of an NIH Roadmap cooperative group during its first two years. Med Care. 2007;45:S3–S11. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000258615.42478.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005–2008. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:1179–1194. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gross AL, Jones RN, Inouye SK. Development of an Expanded Measure of Physical Functioning for Older Persons in Epidemiologic Research. Res Aging. 2015;37:671–694. doi: 10.1177/0164027514550834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:702–706. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zou GY, Donner A. Extension of the modified Poisson regression model to prospective studies with correlated binary data. Stat Methods Med Res. 2013;22:661–670. doi: 10.1177/0962280211427759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akaike H. A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans Automat Contr. 1974;19:716–723. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pugely AJ, Callaghan JJ, Martin CT, et al. Incidence of and risk factors for 30-day readmission following elective primary total joint arthroplasty: analysis from the ACS-NSQIP. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28:1499–1504. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2013.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Basques BA, Bohl DD, Golinvaux NS, et al. Postoperative length of stay and 30-day readmission after geriatric hip fracture: an analysis of 8434 patients. J Orthop Trauma. 2015;29:e115–120. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000000222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Creditor MC. Hazards of hospitalization of the elderly. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118:219–223. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-118-3-199302010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Inouye SK, Schlesinger MJ, Lydon TJ. Delirium: a symptom of how hospital care is failing older persons and a window to improve quality of hospital care. Am J Med. 1999;106:565–573. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00070-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dharmarajan K, Krumholz HM. Strategies to Reduce 30-Day Readmissions in Older Patients Hospitalized with Heart Failure and Acute Myocardial Infarction. Curr Geriatr Rep. 2014;3:306–315. doi: 10.1007/s13670-014-0103-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Inouye SK, Bogardus ST, Jr, Charpentier PA, et al. A multicomponent intervention to prevent delirium in hospitalized older patients. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:669–676. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199903043400901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Inouye SK, Bogardus ST, Jr, Baker DI, et al. The Hospital Elder Life Program: a model of care to prevent cognitive and functional decline in older hospitalized patients. Hospital Elder Life Program. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:1697–1706. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rubin FH, Neal K, Fenlon K, et al. Sustainability and Scalability of the Hospital Elder Life Program at a Community Hospital. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:359–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03243.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]