Abstract

The aim of this paper is to contribute to the understanding of the pattern formation phenomenon in reaction-diffusion equations coupled with ordinary differential equations. Such systems of equations arise, for example, from modeling of interactions between cellular processes such as cell growth, differentiation or transformation and diffusing signaling factors. We focus on stability analysis of solutions of a prototype model consisting of a single reaction-diffusion equation coupled to an ordinary differential equation. We show that such systems are very different from classical reaction-diffusion models. They exhibit diffusion-driven instability (turing instability) under a condition of autocatalysis of non-diffusing component. However, the same mechanism which destabilizes constant solutions of such models, destabilizes also all continuous spatially heterogeneous stationary solutions, and consequently, there exist no stable Turing patterns in such reaction-diffusion-ODE systems. We provide a rigorous result on the nonlinear instability, which involves the analysis of a continuous spectrum of a linear operator induced by the lack of diffusion in the destabilizing equation. These results are extended to discontinuous patterns for a class of nonlinearities.

Keywords: Pattern formation, Reaction-diffusion equations, Autocatalysis, Turing instability, Unstable stationary solutions

Introduction

In this paper we focus on diffusion-driven instability (DDI) in systems of equations consisting of a single reaction-diffusion equation coupled with an ordinary differential equation system. Such systems are important for systems biology applications; they arise for example in modeling of interactions between processes in cells and diffusing growth factors, such as in refs. Hock et al. (2013), Klika et al. (2012), Marciniak-Czochra (2003), Marciniak-Czochra and Kimmel (2006, 2008), Pham et al. (2011), Umulis et al. (2006). In some cases they can be obtained as homogenization limits of models describing coupling of cell-localized processes with cell-to-cell communication via diffusion in a cell assembly (Marciniak-Czochra and Ptashnyk 2008; Marciniak-Czochra 2012). Other examples are discussed e.g. in refs. Chuan et al. (2006), Evans (1975), Marciniak-Czochra et al. (2015), Mulone and Solonnikov (2009), Wang et al. (2013) and in the references therein. A detailed discussion of the DDI phenomena in the three-component systems with some diffusion coefficients equal to zero is found in the recent work (Anma et al. 2012).

Diffusion-driven instability, also called the Turing instability, is a mechanism of de novo pattern formation, which has been often used to explain self-organization observed in nature. DDI is a bifurcation that arises in a reaction-diffusion system, when there exists a spatially homogeneous stationary solution which is asymptotically stable with respect to spatially homogeneous perturbations but unstable to spatially heterogeneous perturbations. Models with DDI describe a process of a destabilization of stationary spatially homogeneous steady states and evolution of the system towards spatially heterogeneous steady states. DDI has inspired a vast number of mathematical models since the seminal paper of Turing (1952), providing explanations of symmetry breaking and de novo pattern formation, shapes of animal coat markings, and oscillating chemical reactions. We refer the reader to the monographs by Murray (2002, 2003) and to the review article (Suzuki 2011) for references on DDI in the two component reaction-diffusion systems and to the paper Satnoianu et al. (2000) in the several component systems.

However, in many applications there are components which are localized in space, which leads to systems of ordinary differential equations coupled with reaction-diffusion equations. Our main goal is to clarify in what manner such models are different from the classical Turing-type models and to demonstrate that the spatial structure of the pattern emerging via DDI cannot be determined based on linear stability analysis.

To understand the role of non-diffusive components in the pattern formation process, we focus on systems involving a single reaction-diffusion equation coupled to ODEs. It is an interesting case, since a scalar reaction-diffusion equation cannot exhibit stable spatially heterogenous patterns (Casten and Holland 1978) and hence in such models it is the ODE component that yields the patterning process. As shown in ref. Marciniak-Czochra et al. (2013), it may happen that there exist no stable stationary patterns and the emerging spatially heterogeneous structures are of a dynamical nature. In numerical simulations of such models, solutions having the form of unbounded periodic or irregular spikes have been observed (Härting and Marciniak-Czochra 2014).

Thus, the aim of this work is to investigate to which extent the results obtained in Marciniak-Czochra et al. (2013), concerning the instability of all stationary structures, apply to a general class of reaction-diffusion-ODE models with a single diffusion operator.

We focus on the following two-equation system

| 1.1 |

| 1.2 |

in a bounded domain for , with a -boundary , supplemented with the Neumann boundary condition

| 1.3 |

where and denotes the unit outer normal vector to , and with initial data

| 1.4 |

The nonlinearities and are arbitrary -functions. Notice that Eq. (1.2) may contain an arbitrary diffusion coefficient which, however, can be rescaled and assumed to be equal to one.

In this paper we investigate stability properties of stationary solutions of the problem (1.1)–(1.3). Our main results are Theorems 2.1 and 2.11 which assert that, under a natural assumption satisfied by a wide variety of systems, stationary solutions are unstable. We call this assumption the autocatalysis condition (see Theorem 2.1) following its physical motivation in the model. We show in Section 3 that this condition is satisfied for all stationary solutions of a wide class of systems from mathematical biology. Our results are different in continuous and discontinuous stationary solutions. In the latter case, additional assumptions on the structure of nonlinearities are required.

As a complementary result to the instability theorems, we prove Theorem 2.9 which states that each non-constant regular stationary solution intersecting (in a sense to be defined) constant steady states with the DDI property, has to satisfy the autocatalysis condition. It is a classical idea by Turing that stable patterns appear around the constant steady state in systems of reaction-diffusion equations with DDI. Mathematical results on stability of such patterns can be found, e.g., in refs. Iron et al. (2004), Wei (2008), Wei and Winter (2007, 2008, 2014) and in the references therein. In the current work, combining Theorems 2.1 and 2.9, we show that this is not the case in the reaction-diffusion-ODE problems (1.1)–(1.4). In other words, the same mechanism which destabilizes constant solutions of such models, destabilizes also non-constant stationary solutions, a behavior that does not fit the usual paradigm of the reaction-diffusion-type equations. See Remark 2.10 for more details.

Mathematically, in the proof of our main result we need to consider a nonempty continuous spectrum of the linearized operator. This seems to be a novelty in the study of reaction-diffusion equations, and is caused by the absence of diffusion in one of the equations. In Section 4, we provide a rigorous proof of the nonlinear instability of steady states by using ideas from fluid dynamics equations.

The paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we state the main results. Section 3 provides relevant mathematical biology-related examples of reaction-diffusion-ODE systems. Proofs are postponed to Sects. 4 and 5. Section 4 is devoted to showing instability of the stationary solutions under the autocatalysis condition. A proof of the instability of discontinuous solutions requires additional conditions on the model nonlinearities. In Section 5, the continuous stationary solutions are characterized and it is shown that the autocatalysis condition is satisfied in the class of reaction-diffusion-ODE problems (1.1)–(1.4) exhibiting DDI. Appendix contains additional information on the model of early carcinogenesis which was the main motivation for our research.

Results and comments

First we formulate a condition which leads to instability of regular stationary solutions of the problem (1.1)–(1.4). Then, we show that it is the necessary condition for DDI in reaction-diffusion-ODE systems. Finally, we extend the instability results to a class of discontinuous stationary solutions satisfying additional assumptions.

Instability of regular steady states

First, we focus on regular stationary solutions (U, V) of problem (1.1)–(1.3). For this, we assume that there exists a solution (not necessarily unique) of the equation that is given by the relation for all with a -function . Then, every regular solution (U, V) of the boundary value problem

| 2.1 |

| 2.2 |

| 2.3 |

satisfies the elliptic problem

| 2.4 |

| 2.5 |

where

| 2.6 |

We show that all regular stationary solutions of the problem (1.1)–(1.4) are unstable under a simple assumption on the first equation.

Theorem 2.1

(Instability of regular solutions) Let (U, V) be a regular solution of the problem (2.1)–(2.3) satisfying the following “autocatalysis condition”:

| 2.7 |

Then, (U, V) is an unstable solution of the initial-boundary value problem (1.1)–(1.4).

Inequality (2.7) can be interpreted as autocatalysis in the dynamics of u at the steady state (U, V) at some point . Stability of the stationary solution is understood in the Lyapunov sense. Moreover, we prove nonlinear instability of the stationary solutions of the problem (1.1)–(1.3) and not only their linear instability, i.e. the instability of zero solution of the corresponding linearized problem, see Section 4 for more explanations.

Each constant solution of the problem (2.1)–(2.3) is a particular case of a regular solution. Thus, Theorem 2.1 provides a simple criterion for the diffusion-driven instability (DDI) of .

Corollary 2.2

If a constant solution of the problem (1.1)–(1.4) (namely, and ) satisfies the inequalities

| 2.8 |

then it has the DDI property.

This corollary follows directly from Theorem 2.1, because the second and the third inequality in (2.8) imply that is stable under homogeneous perturbations; see Remark 2.4 for more details.

Sufficient conditions for autocatalysis

Next, we show that DDI in the problem (1.1)–(1.4) implies the autocatalysis condition (2.7).

We consider only a non-degenerate constant stationary solution of the reaction-diffusion-ODE system (1.1)–(1.3). Hence, in the remainder of this work we make the following assumption.

Assumption 2.3

(Non-degeneracy of the stationary solutions) Let all stationary solutions, i.e. vectors such that and , satisfy

| 2.9 |

Remark 2.4

Let us note that the first two conditions in (2.9) allow us to study the asymptotic stability of treated as a solution of the corresponding system of ordinary differential equations

| 2.10 |

by analyzing eigenvalues of the corresponding linearization matrix. Indeed, the conditions for linearized stability read

- If

then the Jacobi matrix2.11

has all eigenvalues with negative real parts, and hence is an asymptotically stable solution of system (2.10).2.12

Now, we state a simple but fundamental property of the stationary solutions of the problem (1.1)–(1.4).

Proposition 2.5

Assume that (U, V) is a non-constant regular solution of the stationary problem (2.1)–(2.3). Then, there exists , such that the vector is a constant solution of the problem (2.1)–(2.3).

To prove Proposition 2.5, it suffices to integrate equation (2.2) over and to use the Neumann boundary condition (2.3) to obtain Hence, there exists such that , because U and V are continuous. Thus, by Eq. (2.1), it also holds

In the case described by Proposition 2.5, we say that a non-constant solution (U, V) intersects a constant solution . Now, we prove an important property of the constant solutions that are intersected by non-constant regular solutions.

Proposition 2.6

Let be a regular non-constant stationary solution of problem (1.1)–(1.3) and assume that all constant stationary solutions that are intersected by (U, V) are non-degenerate, i.e. relations (2.9) are satisfied. Then, at least at one of those constant solutions, denoted here by , the following inequality holds

| 2.14 |

The proof of Proposition 2.6 is based on the properties of the solutions of the elliptic Neumann problem (2.4)–(2.5) (see Theorem 5.1, below), which we prove in Sect. 5.

Remark 2.7

Every non-degenerate constant solution of the problem (1.1)–(1.4) satisfying inequality (2.14) is unstable. If both factors on the left-hand side of inequality (2.14) are positive, then, in particular, the autocatalysis condition is satisfied. Hence, the constant solution is an unstable solution of the reaction-diffusion-ODE system (1.1)–(1.4) by Theorem 2.1. On the other hand, if both factors on the left-hand side of inequality (2.14) are negative, then, in particular, the determinant in inequality (2.14) is negative and the constant vector is an unstable solution of the corresponding kinetic system (2.10), see the alternative (2.13) in Remark 2.4.

Remark 2.8

It is worth to emphasize the following particular case of the phenomenon described in Remark 2.7, because we shall encounter it in our examples, further on. Suppose that the problem (1.1)–(1.4) has a non-constant regular stationary solution (U, V) intersecting only one constant and non-degenerate steady state which is asymptotically stable as a solution of the kinetic system (2.10). In such case, inequality (2.14) together with the second inequality in (2.11) directly imply the autocatalysis condition Thus, by Theorem 2.1, is an unstable solution of the reaction-diffusion-ODE problem (1.1)–(1.4), i.e. the constant steady state has the DDI property. Below, in Theorem 2.9, we show that the non-constant stationary solution (U, V) also satisfies the autocatalysis condition (2.7), and hence, it is unstable.

Now, we are in the position to show that the autocatalysis condition (2.7) has to be satisfied in reaction-diffusion-ODE systems (1.1)–(1.3) with non-constant regular stationary solutions which intersect constant steady states with the DDI property.

Theorem 2.9

Let (U, V) be a non-constant regular stationary solution of problem (1.1)–(1.4). Denote by a non-degenerate constant solution which intersects (U, V), and satisfies inequality (2.14). Assume that is an asymptotically stable solution of the kinetic system (2.10). Then, there exists such that

The following remark emphasizes importance of the above results.

Remark 2.10

The instability results from Theorem 2.1 and Corollary 2.2 combined with Theorem 2.9 can be summarized in the following way. This is a classical idea that, in a system of reaction-diffusion equations with a constant solution having the DDI property, one expects stable patterns to appear around that constant steady state. Such stationary solutions are called the Turing patterns. For the initial-boundary value problem for a reaction-diffusion-ODE system with a single diffusion equation (1.1)–(1.3), such stationary solutions can be constructed in the case of several models of interest (see Section 3). However, the same mechanism that destabilizes constant solutions of such models, also destabilizes the non-constant solutions. In other words, all Turing patterns in the reaction-diffusion-ODE problems (1.1)–(1.3) are unstable.

Instability of non-regular steady states

The initial-boundary value problem (1.1)–(1.4) may also have non-regular steady states in the case when the equation is not uniquely solvable. Choosing different branches of solutions of the equation , we obtain the relation with a discontinuous, piecewise -function k. Here, we recall that a pair is a weak solution of problem (2.1)–(2.3) if the equation is satisfied for almost all and if

holds for all test functions .

In this work, we do not prove the existence of such discontinuous solutions and we refer the reader to classical works (Aronson et al. 1988; Mimura et al. 1980; Sakamoto 1990) as well as to our recent paper Marciniak-Czochra et al. (2013, Thm. 2.9) for information about how to construct such solutions to one dimensional problems using phase portrait analysis. Our goal is to formulate a counterpart of the autocatalysis condition (2.7), which leads to instability of the weak (including discontinuous) stationary solutions.

Theorem 2.11

Assume that (U, V) is a weak bounded solution of the problem (2.1)–(2.3) satisfying the following counterpart of the autocatalysis condition

| 2.15 |

for some constants . Suppose, moreover, that there exists such that is continuous in a neighborhood of . Then, (U, V) is an unstable solution of the initial-boundary value problem (1.1)–(1.4).

We prove Theorem 2.11 in Subsect. 4.6 by applying ideas developed for the analysis of the Euler equation and other fluid dynamics models. In that approach, it suffices to show that the spectrum of the linearized operator

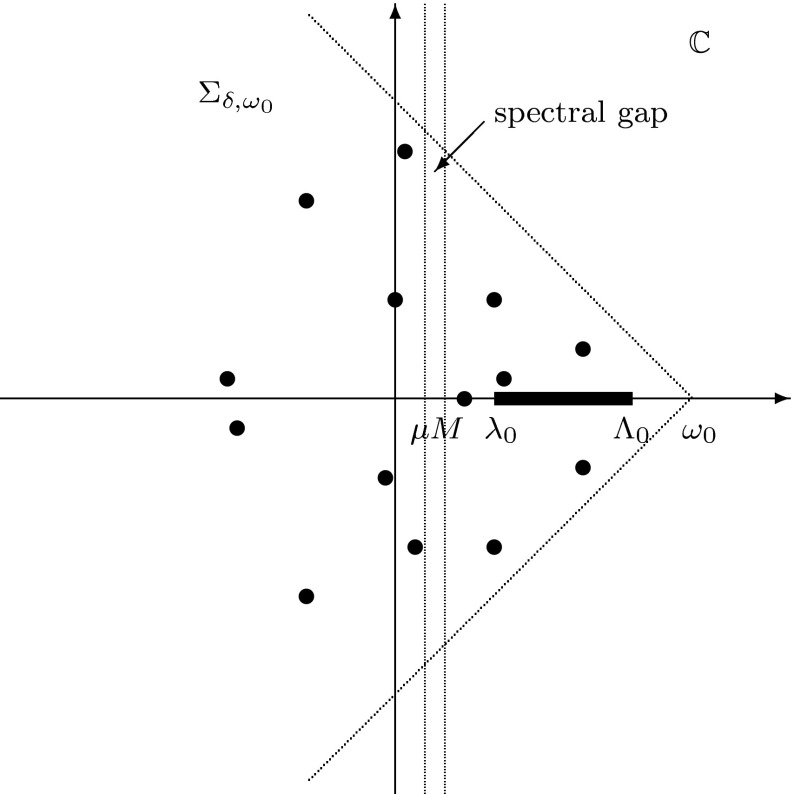

with the Neumann boundary condition has so-called spectral gap, namely, there exists a subset of the spectrum , which has a positive real part, separated from zero. Here, we prove that consists of the set and of isolated eigenvalues of , see Section 4 and, in particular, Fig. 1 for more detail. One should emphasize that the instability of steady states from Theorems 2.1 and 2.11 is caused not by an eigenvalue with a positive real part, but rather by positive numbers from the set which is contained in the continuous spectrum of the operator , see Theorem 4.5 below for more details.

Fig. 1.

The spectrum is marked by thick dots and by the interval in the sector . The spectral gap is represented by the strip without elements of

In fact, in the case of particular nonlinearities, we do not need to assume that condition (2.15) holds true for almost all . Indeed, if , one may have stationary solutions such that on a subset of and on a complement. Such stationary solutions can be, for example, constructed for the carcinogenezis model (3.5)–(3.7) presented below (see Marciniak-Czochra et al. (2013)), and for several other one-dimensional equations discussed in ref. Mimura et al. (1980). In the following corollary, we show instability of the discontinuous stationary solutions, under the autocatalysis condition only for such that .

Corollary 2.12

(Instability of weak solutions) Assume that the nonlinear term in the equation (1.1) satisfies for all . Suppose that (U, V) is a weak bounded solution of the problem (2.1)–(2.3) with the following property: There exist constants such that

| 2.16 |

Moreover, suppose that there exists such that and the functions and are continuous in the neighborhood of . Then, (U, V) is an unstable solution of the initial-boundary value problem (1.1)–(1.4).

Remark 2.13

A typical nonlinearity satisfying the assumptions of Corollary 2.12 has the form . It can be found in the models, where the unknown variable u evolves according to the Malthusian law with a density dependent growth rate r.

We defer the proofs of Theorems 2.1 and 2.11 as well as of Corollary 2.12 to Subsection 4.6. Theorem 2.9 is somewhat independent of Theorems 2.1 and 2.11 and it is proven in Section 5.

Model examples

In this section, our results are illustrated by applying them to some models from mathematical biology.

Gray–Scott model

First we consider a reaction-diffusion-ODE model with nonlinearities as in the celebrated Gray-Scott system describing pattern formation in chemical reactions (Gray and Scott 1983). The system with a non-diffusing activator takes the form

| 3.1 |

| 3.2 |

with the zero-flux boundary condition for v and with nonnegative initial conditions. The constants B and k are assumed to be positive. The system exhibits the instability phenomenon described in Sect. 2.

Here, every regular positive stationary solution (U, V) of the Neumann boundary-initial value problem for equations (3.1)–(3.2) has to satisfy the relation , hence,

| 3.3 |

| 3.4 |

All continuous positive solutions of such boundary value problem in one dimensional case have been constructed in our recent paper Marciniak-Czochra et al. (2013, Sec. 5). A construction of discontinuous stationary solutions of the reaction-diffusion-ODE problem for (3.1)–(3.2) can be also found in Marciniak-Czochra et al. (2013, Thm. 2.9).

Instability results in Theorems 2.1 and 2.9 imply that all stationary solutions (constant, regular as well as discontinuous) of the reaction-diffusion-ODE problem (3.1)–(3.2) are unstable under heterogeneous perturbations. For the proof, it suffices to notice that the autocatalysis assumptions (2.7) and (2.15) are satisfied, since, for , the function is independent of x and satisfies

Model of early carcinogenesis

The main motivation for the research reported in this work has been the study of the reaction-diffusion system of three ordinary/partial differential equations modeling the diffusion-regulated growth of a cell population of the following form

| 3.5 |

| 3.6 |

| 3.7 |

supplemented with zero-flux boundary conditions for the function w and with nonnegative initial conditions, Marciniak-Czochra et al. (2013). Here, the letters denote positive constants.

The theory developed in this paper applies to a reduced two-equation version of the model (3.5)–(3.7), obtained using a quasi-steady state approximation of the dynamics of v. Applying the quasi-steady state approximation in Eq. (3.6) (i.e., setting ), we obtain the relation which after substituting into the remaining Eqs. (3.5) and (3.7) yields the initial-boundary value problem for the following reaction-diffusion-ODE system

| 3.8 |

| 3.9 |

A rigorous derivation of the two equation model (3.8)–(3.9) from the model (3.5)–(3.7) as well as other properties of the solutions to (3.8)–(3.9) are presented in Appendix A of this work. Moreover, numerical simulations suggest that the two-equation model exhibits qualitatively the same dynamics as system (3.5)–(3.7).

The autocatalysis assumptions (2.7) and (2.15) are satisfied by simple calculations, similar to those in the previous example (see Marciniak-Czochra et al. (2013) for more details). As a consequence, all nonnegative stationary solutions of the system (3.8)–(3.9) (regular and non-regular) are unstable due to Theorems 2.1 and 2.11. This corresponds to our results on the three-equation model (3.5)–(3.7) proved in ref. Marciniak-Czochra et al. (2013).

Stability analysis of the space homogeneous solutions of the two equation model (3.8)–(3.9) is reported in Appendix B. In particular, by Remark 2.7, constant steady states of (3.8)–(3.9) are either unstable solutions of the corresponding kinetic system or they have the DDI property.

Model of glioma invasion

Our results can be also applied to the “go-or-grow” model introduced in ref. Pham et al. (2011) to investigate the dynamics of a population of glioma cells switching between a migratory and a proliferating phenotype in dependence on the local cell density. The model consists of two reaction-diffusion equations

| 3.10 |

| 3.11 |

where tumor cells are decomposed into two sub-populations: a migrating population with density v(x, t) and a proliferating population with density u(x, t) (Caution: we changed the notation from Pham et al. (2011), where and ). In this model, the constant is the rate at which cells change their phenotype and the constant is the proliferation rate. The function has the following explicit form

with constant and . It describes two complementary mechanisms for the phenotypic transmissions.

Go-or-rest model. Let us first look at a particular version of model (3.10)–(3.11) with no proliferation rate (namely ) which is called in Pham et al. (2011) as the “go-or-rest model”:

| 3.12 |

| 3.13 |

One can check by a simple calculation that this system supplemented with the Neumann boundary condition for v(x, t) has a one parameter family of constant stationary solutions:

| 3.14 |

These vectors are degenerate (i.e. they do not satisfy Assumption 2.3) because the determinant in (2.9) vanishes in this case. However, by an elementary analysis of the phase portrait of the system of the ODEs,

| 3.15 |

one can show that vectors (3.14) are stable solutions of system (3.15). The constant steady state (3.14) satisfies the autocatalysis condition (2.7) if

| 3.16 |

see Pham et al. (2011, Ch. 3.1) for further discussion. Thus, by our Theorem 2.1, constant stationary solutions (3.14) are unstable solutions of the reaction-diffusion-ODE system (3.12)–(3.13).

System (3.12)–(3.13) has no heterogeneous stationary solutions, because the counterpart of the boundary-value problem (2.1)–(2.3) reduces in this case to the problem

which has constant solutions, only.

Go-or-grow model. Let us now briefly sketch an analogous reasoning in the case of the more general model (3.10)–(3.11) with . It has two constant stationary solutions (cf. Pham et al. (2011)):

The nontrivial steady state is a stable solution of the kinetic system corresponding to (3.10)–(3.11) and it satisfies the autocatalysis condition (2.7) if (see Pham et al. (2011)). In this case, by Theorem 2.1, it is an unstable solution of the reaction-diffusion-ODE system (3.10)–(3.11).

It is beyond the scope of this work to study positive heterogeneous stationary solutions of the go-or-grow model with . However, if there exist regular and strictly positive stationary solutions, then under the assumption , they must be unstable by Theorems 2.1 and 2.9, see also Remark 2.10. In conclusion, the structures shown in simulations of the models in ref. Pham et al. (2011) are not Turing patterns.

Instability of the stationary solutions

Existence of solutions

We begin our study of properties of solutions to the initial-boundary value problem (1.1)–(1.4) by recalling results on local-in-time existence and uniqueness of solutions for all bounded initial conditions.

Theorem 4.1

(Local-in-time solution) Assume that . Then, there exists such that the initial-boundary value problem (1.1)–(1.4) has a unique local-in-time mild solution .

We recall that a mild solution of problem (1.1)–(1.4) is a pair of measurable functions satisfying the following system of integral equations

| 4.1 |

| 4.2 |

where is the semigroup of linear operators generated by Laplacian with the Neumann boundary condition. Since our nonlinearities and are locally Lipschitz continuous, to construct a local-in-time unique solution of system (4.1)–(4.2), it suffices to apply the Banach fixed point theorem. Details of such a reasoning and the proof of Theorem 4.1 in a case of much more general systems of reaction-diffusion equations can be found eg. in Rothe (1984, Thm. 1, p. 111), see also our recent work Marciniak-Czochra et al. (2013, Ch. 3) for a construction of nonnegative solutions of particular reaction-diffusion-ODE problems.

Remark 4.2

If and are more regular, i.e. if for some we have , and on , then the mild solution of problem (1.1)–(1.4) is smooth and satisfies and . We refer the reader to Rothe (1984, Thm. 1, p. 112) as well as to Garroni et al. (2009) for studies of general reaction-diffusion-ODE systems in the Hölder spaces.

Linearization of reaction-diffusion-ODE problems

Let (U, V) be a stationary solution of problem (1.1)–(1.4) — either regular as discussed in Subsection 2.1 or weak (and possibly discontinuous) as defined in Subsection 2.3. Substituting

into (1.1)–(1.2) we obtain the initial-boundary value problem for the perturbation of the form (4.20):

| 4.3 |

with the Neumann boundary condition, where the linear operator and the nonlinearity are defined by formulas (4.4) and (4.6), resp.

Lemma 4.3

Let (U, V) be a bounded (not necessarily regular) stationary solution of problem (1.1)–(1.4). We consider the following linear system

| 4.4 |

with the Neumann boundary condition Then, for every , the operator with the domain generates an analytic semigroup of linear operators on , which satisfies “the spectral mapping theorem”:

| 4.5 |

Proof

Here, we use the Sobolev space

Notice that is a bounded perturbation of the operator

with the domain , which generates an analytic semigroup on for each . Thus, it is well-known (see e.g.Engel and Nagel (2000, Ch. III.1.3) and Yagi (2010, Theorems 2.15 and 2.19)) that the same property holds true for the operator .

The spectral mapping theorem for the semigroup expressed by equality (4.5) holds true if the semigroup is e.g. eventually norm-continuous (see Engel and Nagel (2000, Ch. IV.3.10)). Since every analytic semigroup of linear operators is eventually norm-continuous, we obtain immediately relation (4.5) (cf. Engel and Nagel (2000, Ch. IV, Corollary 3.12)).

Next, we show certain elementary estimate of the nonlinearity in equation (4.3).

Lemma 4.4

Let (U, V) be a bounded (not necessarily regular) stationary solution of problem (1.1)–(1.4). Then, for every , the nonlinear operator

| 4.6 |

satisfies

| 4.7 |

for all such that and , where is an arbitrary constant. If, moreover, then

| 4.8 |

for all such that and , where is an arbitrary constant.

Proof

The proofs of both inequalities consist in using the Taylor formula applied to the -nonlinearities and in problem (1.1)–(1.2).

Continuous spectrum of the linear operator

Now, we are in a position to study the spectrum of the linear operator , given by the formula (4.4) when we linearize the reaction-diffusion-ODE problem (1.1)–(1.4) at a regular stationary solution.

Theorem 4.5

Assume that (U(x), V(x)) is a regular stationary solution of the problem (1.1)–(1.4) and define the constants

| 4.9 |

Fix . Let be the linear operator defined formally by formula (4.4) with the domain . Then

Proof

We show that for each the operator

defined by formula

where , etc., cannot have a bounded inverse. Suppose, a contrario, that exists and is bounded. Then, for a constant , we have

for all or, equivalently, using the usual norms in and in :

| 4.10 |

A contradiction will be obtained by showing that inequality (4.10) cannot be true for all .

To prove this claim, first we observe that, for each , there exists such that . Hence, for every there is a ball such that

Next, for arbitrary satisfying , we choose such that and in such a way that , where the function satisfies . Let us explain that such a choice of is always possible. We cut at the level in the following way

Thus, we obtain

for

with

Now, noting that , we obtain the inequality

Thus, substituting functions , , and into inequality (4.10), we obtain the estimate

| 4.11 |

Hence, choosing in such a way that and compensating the term on the right-hand side of inequality (4.11) by its counterpart on the left-hand side, we obtain the estimates

which, obviously, cannot be true for all such that .

We have completed the proof that each belongs to .

Eigenvalues

In the Hilbert case , the remainder of the spectrum of consists of a discrete set of eigenvalues . Here, we sketch the proof of this result, however, it does not play any role in our instability results.

As the usual practice, we analyze the corresponding resolvent equations

| 4.12 |

| 4.13 |

| 4.14 |

with arbitrary . Here, one should notice that for every , one can solve equation (4.12) with respect to . Thus, after substituting the resulting expression into (4.13), we obtain the boundary value problem

| 4.15 |

| 4.16 |

where

| 4.17 |

For a fixed , by the Fredholm alternative, either the inhomogeneous problem (4.15)–(4.16) has a unique solution (so, is not an element of ) or else the homogeneous boundary value problem

| 4.18 |

| 4.19 |

has a nontrivial solution . Hence, it suffices to consider those , for which problem (4.18)–(4.19) has nontrivial solution.

Now, we are in a position to prove that the set consists of isolated eigenvalues of , only. Here, it suffices to use the following general result on a family of compact operators, which we state for the reader’s convenience. The proof can be found in the Reed and Simon book Reed and Simon (1980, Thm. VI.14).

Theorem 4.6

(Analytic Fredholm theorem) Assume that H is a Hilbert space and denote by L(H) the Banach space of all bounded linear operators acting on H. For an open connected set , let be an analytic operator-valued function such that f(z) is compact for each . Then, either

exists for no , or

exists for all , where S is a discrete subset of D (i.e. a set which has no limit points in D).

Let us rewrite problem (4.18)–(4.19) in the form

where the operator ” supplemented with the Neumann boundary conditions is defined in the usual way. Here, is a fixed number different from each eigenvalue of Laplacian with the Neumann boundary condition.

Recall that, for each , the operator is compact as the superposition of the compact operator G and of the continuous multiplication operator with the function . Moreover, the mapping from the open set into the Banach space of linear compact operators is analytic, which can be easily seen using the explicit form of in (4.17). Thus, the set consists of isolated points due to the analytic Fredholm Theorem 4.6. Here, to exclude the case (a) in Theorem 4.6, we have to show that the operator is invertible for some . This is, however, the consequence of the fact that the inhomogeneous boundary value problem (4.15)–(4.16) has a unique solution if is chosen so large that .

Linearization principle

The next goal in this section is to recall that, under appropriate conditions, the linear instability of the stationary solutions of a reaction-diffusion-ODE problem implies their nonlinear instability. Such a theorem is well-known for ordinary differential equations. Furthermore, in the case of reaction-diffusion equations where the spectrum of a linearized problem is discrete, one my apply the abstract result from the book by Henry (1981, Thm.5.1.3). However, in the case of reaction-diffusion-ODE problems, the linearized operator at a stationary solution (either smooth or discontinuous) may have a non-empty continuous spectrum (cf. Theorem 4.5). Hence, checking the assumptions of general results from Henry (1981) does not seem to be straightforward. Therefore, here, we propose a different approach.

Let us consider a general evolution equation

| 4.20 |

where is a generator of a -semigroup of linear operators on a Banach space X and is a nonlinear operator such that .

First, we recall an idea introduced by Shatah and Strauss (2000) which asserts that, under relatively strong assumption on a nonlinearity in equation (4.20), the existence of a positive part of the spectrum of the linear operator is sufficient to show that the zero solution of equation (4.3) is unstable. This is the precise statement of that result.

Theorem 4.7

(Shatah and Strauss (2000, Thm 1)) Consider an abstract problem (4.20), where

the linear operator generates a strongly continuous semigroup of linear operators on a Banach space X,

the intersection of the spectrum of with the right half-plane is nonempty.

is continuous and there exist constants , , and such that for all .

Then the zero solution of this equation is (nonlinearly) unstable.

We apply Theorem 4.7 to show an instability of regular steady states. In the case of discontinuous stationary solutions, we are unable to show that the nonlinearity in equation (4.3) satisfies the the condition (3) of Theorem 4.7. One may overcome this obstacle by assuming that the the spectrum has so-called spectral gap. This classical method has been recently used by Mulone and Solonnikov Mulone and Solonnikov (2009) to show the instability of regular stationary solutions to certain reaction-diffusion-ODE problems, however, assumptions imposed in Mulone and Solonnikov (2009) are not satisfied in our case.

The crucial idea underlying this approach is to use two Banach spaces: a “large” space Z where the spectrum of a linearized operator is studied and a “small” space where an existence of solutions can be proved. More precisely, let (X, Z) be a pair of Banach spaces such that with a dense and continuous embedding. A solution of the Cauchy problem (4.20) is called (X, Z)-nonlinearly stable if for every , there exists so that if and , then

there exists a global in time solution of (4.20) such that ;

for all .

An equilibrium that is not stable (in the above sense) is called Lyapunov unstable.

In this work, we drop the reference to the pair (X, Z). Let us also note that, under this definition of stability, a loss of the existence of a solution of (4.20) is a particular case of instability.

Now, we recall a result linking the existence of the so-called spectral gap to the nonlinear instability of a trivial solution to problem (4.20).

Theorem 4.8

We impose the two following assumptions.

- The semigroup of linear operators on Z satisfies “the spectral gap condition”, namely, we suppose that for every the spectrum of the linear operator can be decomposed as follows: with , where

and - The nonlinear term satisfies the inequality

for some constants and .4.21

Then, the trivial solution of the Cauchy problem (4.20) is nonlinearly unstable.

The proof of this theorem can be found in the work by Friedlander et al. Friedlander et al. (1997, Thm. 2.1).

Remark 4.9

The operator considered in this work satisfies the “spectral mapping theorem”: , see Lemma 4.3. Thus, due to the relation for every , the spectral gap condition required in Theorem 4.8 holds true if for every , either or .

Remark 4.10

The authors of the reference Friedlander et al. (1997, Thm. 2.1) formulated their instability result under the spectral gap condition for a group of linear operators and in the case of a finite constant (caution: in Friedlander et al. (1997), the letter is used instead of ). However, the proof of Friedlander et al. (1997, Thm. 2.1) holds true (with a minor and obvious modification) in the case of a semigroup as well as is allowed, as stated in Theorem 4.8. This extension is important to deal with the operator introduced in Lemma 4.3, which generates a semigroup of linear operators, only, and which may have an unbounded sequence of eigenvalues.

Proofs of instability results

Proof of Theorem 2.1

Here, it suffices to apply Theorem 4.7 to the semi-linear equation (4.3) with the Banach space

Recall the well-known embedding for every ..

We refer the reader to Yagi (2010, Ch. 2) for the proof that the operator discussed in Lemma 4.3 generates a semigroup of linear operators on X. The autocatalysis condition (2.7) combined with Theorem 4.5 imply that meets the right-hand plane of . Due to the embedding , inequalities (4.7) and (4.8) imply that the nonlinear mapping in (4.6) satisfies the condition (3) of Theorem 4.7 with .

Hence, the regular stationary solution (U, V) is unstable.

Proof of Theorem 2.11

To show an instability of non-regular stationary solution, we begin as in the proof of Theorem 2.1. First, we linearize our problem at a weak bounded stationary solution (U, V) and we notice that assumptions of Lemmas 4.3 and 4.4 are satisfied. Next, following the arguments from the proof of Theorem 4.5 we show that the number belongs to , where is positive at and continuous in its neighborhood. Notice that we do not need to show that all numbers from are in to show the spectral gap condition required by Theorem 4.8. The reasoning from Subsection 4.4 concerning eigenvalues can be copied here without any change because defined in (4.17) is a bounded function for every .

Now, let us show that the operator has a spectral gap as required in assumption (1) of Theorem 4.8.

By Lemma 4.3, there exists a number such that the operator generates a bounded analytic semigroup on ; hence, this is a sectorial operator, see Engel and Nagel (2000, Ch. II, Thm. 4.6). In particular, there exists such that see Fig. 1. A part of the spectrum in the triangle consists of the interval where and of a discrete set of eigenvalues (by discussion in Subsection 4.4) with accumulation points from the interval , only (by Theorem 4.6.b). Thus, we can easily find infinitely many for which the spectrum can be decomposed as required in Theorem 4.8. Here, one should use the spectral mapping theorem, i.e. equality (4.5), and Remark 4.9.

Now, to complete the proof of an instability of not-necessarily regular stationary solutions, we apply Theorem 4.8 with and for a bounded domain with a regular boundary, supplemented with the usual norms. Then, required estimate of the nonlinear mapping in (4.21) is stated in inequality (4.7) with .

Proof of Corollary 2.12

Here, the analysis is similar to the case of regular stationary solutions discussed in Theorem 2.1, hence, we only emphasize the most important steps.

Let (U, V) be a weak solution of problem (2.1)–(2.3) and denote by its null set, namely, a measurable set such that for all and for all . For a null set , we define the associate -space

supplemented with the usual -scalar product, which is a Hilbert space as the closed subspace of . In the same way, we define the subspace by the equality .

Obviously, when the measure of equals zero, we have . The imposed assumptions imply that is different from the whole interval.

Now, observe that if for some then by equations (1.1) with the nonlinearity we have for all . Hence, the spaces

| 4.22 |

are invariant for the flow generated by problem (1.1)–(1.4) (notice that there is no “” in the second coordinates of and ). The crucial part of our analysis is based on the fact that, as long as we work in the space and , we can linearize problem (1.1)–(1.4) at the weak solution (U, V). Moreover, for each , the corresponding linearized operator agrees with defined in Lemma 4.3. Hence, the analysis from the proof of Theorem 2.1 can be directly adapted to discontinuous steady states in the following way.

We fix a weak stationary solution with a null set . The Fréchet derivative of the nonlinear mapping defined by the mappings at the point has the form

where

This results immediately from the definition of the Fréchet derivative.

Next, we study spectral properties of the linear operator

in the Hilbert space (see (4.22)) with the domain Here, the reasoning from the proof of Theorem 2.1 can be directly adapted with modifications as in the proof of Theorem 2.11.

Finally, we may study the discrete spectrum of in the same way as in Subsection 4.4 because the corresponding function is bounded for . The proof of instability of the stationary solution is completed by Theorem 4.8 and Lemmas 4.3-4.4.

Constant steady states which are intersected by non-constant stationary solutions

First, we prove a certain property of stationary solutions to a general elliptic Neumann problem. This result will imply immediately Proposition 2.6.

Theorem 5.1

Assume that is a non-constant solution of the boundary value problem

| 5.1 |

Then, there exists and such that

| 5.2 |

Proof

First, as in the proof of Proposition 2.5, we integrate the equation in (5.1) and we use the Neumann boundary condition to obtain Hence, there exists and such that and Now, we suppose that , and consider two cases: and , separately.

Let . Since , we have

Using the well-known formula

we obtain

| 5.3 |

where . Observe that and

Hence, there exists an open neighbourhood of such that for all . Suppose that for all . Multiplying both sides of equation (5.3) by and integrating over , we obtain

This implies that , which is a contradiction, because we assume that is a non-constant solution. Therefore, there exists such that . It follows from equation (5.3) that , and consequently, from equation (5.1) we have . Hence, there exists such that and . Note that . Thus, if the equation has only one root, the proof of Theorem 5.1 is completed.

Now, we consider two cases.

Case I: The equation has no solution between and . Thus, we define the function

and, without loss of generality, we can assume that for all .

Since and , we have for small . If we also suppose that , then, we can find small such that . Noting that is continuous function, we see that there exist such that and . This implies that there exists for which , and from the assumption for ,

This is a contradiction with the hypothesis that the equation has no roots between and . Hence, .

Case II: The equation has a solution between and . It is clear that V(x) has to intersect , too. Choosing the closest root of to , we repeat the argument from Case I to show that .

Next, let . Following the previous reasoning and using the hypothesis , we find a ball such that and for all . Moreover, we can assume that either or for all , because, if there exists such that , then we can apply the same argument as in the first part of this proof to obtain .

Let for all , and we apply the Hopf boundary lemma to equation (5.3) in the ball B. If V is a non-constant solution satisfying and , then necessarily which contradicts the Neumann boundary condition satisfied by V at .

Now, we consider the case for all . Here, the function satisfies the equation

where , for all and . Hence, the Hopf boundary lemma yields a contradiction.

Thus, and the proof is complete.

Proof of Proposition 2.6

Let be a non-constant regular stationary solution of (1.1)–(1.3) which means that and . Since each constant solution is non-degenerate, the equation can be solved locally with respect to U, which implies that is a -function. Substituting into equation (2.2) and denoting , we obtain the following boundary value problem satisfied by :

| 5.4 |

| 5.5 |

By Theorem 5.1, there exists a constant solution of problem (5.4)–(5.5) and such that

| 5.6 |

On the other hand, differentiating the function yields

| 5.7 |

Moreover, we differentiate both sides of the equation with respect to v to obtain . Hence,

| 5.8 |

Finally, choosing and and substituting equation (5.8) into (5.7), we obtain

By (5.6), it holds . Moreover, since is non-degenerate, we obtain . This completes the proof of inequality (2.14).

Acknowledgments

A. Marciniak-Czochra was supported by European Research Council Starting Grant No 210680 “Multiscale mathematical modelling of dynamics of structure formation in cell systems” and Emmy Noether Programme of German Research Council (DFG). The work of G. Karch was partially supported by the NCN grant 2013/09/B/ST1/04412. K. Suzuki acknowledges JSPS the Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) 26400156.

Appendix A. Model of early carcinogenesis – quasi-stationary approximation

In Appedix, we discuss in detail the model example from Subsection 3.2.

Initial-boundary value problems for reaction-diffusion-ODE systems arise in the modeling of the growth of a spatially-distributed cell population, where proliferation is controlled by endogenous or exogenous growth factors diffusing in the extracellular medium and binding to cell surface as proposed by Marciniak and Kimmel in the series of recent papers Marciniak-Czochra and Kimmel (2006, 2007, 2008). Here, we consider the following particular case of such systems, which was studied by us in Marciniak-Czochra et al. (2013)

| 6.1 |

| 6.2 |

| 6.3 |

on , supplemented with zero-flux boundary conditions for

| 6.4 |

and with nonnegative, smooth and bounded initial data

| 6.5 |

In equations (6.1)–(6.3), the letters denote positive constants.

As it was shown in Marciniak-Czochra et al. (2013, Sec. 3), solutions of this problem are nonnegative and stay bounded on every interval [0, T]. Here, we study the behavior of these solutions as .

First, we notice that choosing in equation (6.2), we obtain the identity

| 6.6 |

Substituting it to the two remaining equations (6.1), (6.3) yields the system

| 6.7 |

| 6.8 |

| 6.9 |

| 6.10 |

Repeating our reasoning from Marciniak-Czochra et al. (2013) one can show that this new system has also a unique, global-in-time nonnegative, smooth solution for nonnegative and smooth initial data.

In this part of Appendix, we show that solutions of the quasi-stationary system (6.6)–(6.10) are good approximation of solutions of the original three-equation model (6.1)–(6.5). Our main result concerns uniform estimates for an approximation error for u and w on each finite time interval [0, T].

First, we show that solutions of -problem (6.1)–(6.5) are uniformly bounded with respect to small , locally in time.

Lemma 6.1

For every there exists such for all sufficiently small (e.g. ) the solution of system (6.1)–(6.5) satisfies

for all .

It will be clear from the proof of Lemma 6.1 that the constant C(T) growths exponentially in .

Proof of Lemma 6.1

Since for nonnegative solutions, equation (6.1) yields the inequality,

| 6.11 |

Hence, we have the estimate for all .

Applying the comparison principle to the parabolic equation (6.3) with the Neumann boundary condition we obtain the estimate

| 6.12 |

where the function satisfies the Cauchy problem

| 6.13 |

and is given by the formula

| 6.14 |

Next, we use equation (6.2) to obtain

| 6.15 |

Thus, using inequality (6.11) and plugging the above estimate into (6.14) yields

| 6.16 |

Changing the order of integration, we can simplify the last term on the right-hand side

hence, for , using inequalities (6.12) we obtain

| 6.17 |

where is independent of T and of . Finally, the Gronwall inequality applied to (6.17) implies the estimate

| 6.18 |

and for all sufficiently small (e.g. ), where positive constants C and are independent of .

Finally, estimate (6.18) applied to inequality (6.15) implies an analogous bound for .

Theorem 6.2

Let be a solution of system (6.1)- (6.5) with sufficiently small (e.g. ) and (u, w) be a solution of the corresponding system (6.6)–(6.10). For each , there exists a constant independent of such that

| 6.19 |

| 6.20 |

Additionally, we also have

| 6.21 |

where v is given by equation (6.6).

Proof

Letting , and , we obtain by the Taylor expansion the following system

| 6.22 |

| 6.23 |

| 6.24 |

supplemented with the initial conditions

with obtained from and via formula (6.6), and with the Neumann boundary condition for . In equations (6.22)–(6.24) the following coefficients

are calculated in certain intermediate points and are bounded independently of due to Lemma 6.1.

The proof is divided into three steps.

Step 1: First, applying the comparison principle to the parabolic equation (6.24) with the Neumann boundary condition and with the zero initial datum we obtain the estimate

where is a solution of the Cauchy problem

Since

using the Young inequality for a convolution and the estimate , we obtain

| 6.25 |

Step 2: Next, we estimate the solution of equation (6.23). First, note that

The solution of equation (6.23) satisfies the formula

Consequently, the Young inequality yields

| 6.26 |

where the last inequality results from (6.25). Here, in the first inequality of (6.26), the function v(x, t) is given by formula (6.6). Hence, the quantity is finite (and obviously independent of ) for smooth solutions by equations (6.7) and (6.8).

Step 3: Finally, we estimate the solution of equation (6.22). Note that and

Thus, using the Young inequality again we obtain the estimate

| 6.27 |

as well as

| 6.28 |

Inserting inequality (6.28) into (6.26) leads to

| 6.29 |

For we conclude that

| 6.30 |

Since every can be reached after a finite number of steps, estimate (6.30) holds for every . Furthermore, inequality (6.30) applied in (6.25) and (6.27) completes the proof of estimates (6.19)–(6.21).

Remark 6.3

To obtain a better estimate of , one should construct an initial value layer, since .

Appendix B. Model of early carcinogenesis – constant steady states

Here, we consider the space homogeneous solutions of the two-equation model (6.6)–(6.10) which satisfy the corresponding kinetic system

| 7.1 |

| 7.2 |

where a, , , d, , are positive constants and we have always assumed that . The structure of constant steady states of this system is the same as of the original three-equation model and can be characterized by the following lemma (for the proof see Marciniak-Czochra et al. (2013)).

Lemma 7.1

Let . If , then system (7.1)–(7.2) has two positive steady states and with

| 7.3 |

Theorem 7.2

Let and be positive steady states of system (7.1)–(7.2) given by (7.3). Then is always unstable. While is stable, except for the case

where

Proof

Let denote a steady state of (7.1)–(7.2). From direct calculations, the Jacobian matrix J at of the nonlinear mapping defined by the right-hand side of (7.1)–(7.2) is of the form

We know (cf. Remark 2.4) that

-

(i)if

then all eigenvalues of J have negative real parts;7.4 -

(ii)if

then there is an eigenvalue of J which has a positive real part.7.5

Step 1. First, we show the stability of . Using estimates (7.3), the second inequality of (7.5) can be written in the form

| 7.6 |

Note that the left-hand side of (7.6) satisfies

and satisfies . Therefore, it follows from the assumption that

which implies that the steady state is unstable.

Step 2. Next, we show stability of . The second inequality of (7.4) is equivalent to . The latter inequality holds true, since and

Using (7.3) and the relationship , the first condition of (7.4) becomes

If , then the above inequality always holds.

Assume . Note that is given by

Therefore, it is sufficient to show the following inequality

| 7.7 |

The left-hand side of (7.7) is

Hence, if

| 7.8 |

then inequality (7.7) holds true. Noting , we obtain, from (7.8), that

| 7.9 |

what is equivalent to

| 7.10 |

If and , then inequality (7.10) is always satisfied since the right-hand side of (7.10) is positive. The remaining cases are (i) and (ii) and . In the cases (i) and (ii), the both-sides of (7.10) are positive. Therefore, we calculate the square of both sides of (7.10) and obtain

| 7.11 |

If , then , while if . Therefore, the inequality (7.10) holds in case (ii). In case (i), (7.10) is satisfied under the condition (7.11).

Contributor Information

Anna Marciniak-Czochra, Email: anna.marciniak@iwr.uni-heidelberg.de, http://www.biostruct.uni-hd.de/.

Grzegorz Karch, Email: grzegorz.karch@math.uni.wroc.pl, http://www.math.uni.wroc.pl/~karch.

Kanako Suzuki, Email: kanako.suzuki.sci2@vc.ibaraki.ac.jp.

References

- Anma A, Sakamoto K, Yoneda T. Unstable subsystems cause Turing instability. Kodai Math J. 2012;35(2):215–247. doi: 10.2996/kmj/1341401049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aronson DG, Tesei A, Weinberger H. A density-dependent diffusion system with stable discontinuous stationary solutions. Ann Mat Pura Appl (4) 1988;152:259–280. doi: 10.1007/BF01766153. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Casten R, Holland C. Instability results for reaction-diffusion equations with Neumann boundary conditions. J Differ Equ. 1978;27:266–273. doi: 10.1016/0022-0396(78)90033-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chuan Le H, Tsujikawa T, Yagi A. Asymptotic behavior of solutions for forest kinematic model. Funkcial Ekvac. 2006;49:427–449. doi: 10.1619/fesi.49.427. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Engel K-L, Nagel R (2000) One-parameter semigroups for linear evolution equations, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, 194. Springer-Verlag, New York

- Evans JW (1975) Nerve axon equations. IV. The stable and the unstable impulse. Indiana Univ Math J 24(12):1169–1190

- Friedlander S, Strauss W, Vishik M. Nonlinear instability in an ideal fluid. Ann Inst H Poincaré Anal Non Linéaire. 1997;14:187–209. doi: 10.1016/S0294-1449(97)80144-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garroni MG, Solonnikov VA, Vivaldi MA. Schauder estimates for a system of equations of mixed type. Rend Mat Appl. 2009;29:117–132. [Google Scholar]

- Gray P, Scott SK. Autocatalytic reactions in the isothermal continuous stirred tank reactor: isolas and other forms of multistability. Chem Eng Sci. 1983;38:29–43. doi: 10.1016/0009-2509(83)80132-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Härting S, Marciniak-Czochra A. Spike patterns in a reaction-diffusion ODE model with Turing instability. Math Meth Appl Sci. 2014;37:1377–1391. [Google Scholar]

- Henry D. Geometric theory of semilinear parabolic equations. New York: Springer; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Hock S, Ng Y, Hasenauer J, Wittmann D, Lutter D, Trümbach D, Wurst W, Prakash N, Theis FJ. Sharpening of expression domains induced by transcription and microRNA regulation within a spatio-temporal model of mid-hindbrain boundary formation. BMC Syst Biol. 2013;7:48. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-7-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iron D, Wei J, Winter M. Stability analysis of Turing patterns generated by the Schnakenberg model. J Math Biol. 2004;49:358–390. doi: 10.1007/s00285-003-0258-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klika V, Baker RE, Headon D, Gaffney EA. The influence of receptor-mediated interactions on reaction-diffusion mechanisms of cellular self-organization. Bull Math Biol. 2012;74:935–957. doi: 10.1007/s11538-011-9699-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladyzenskaja OA, Solonnikov VA (1973) The linearization principle and invariant manifolds for problems of magnetohydrodynamics. Boundary value problems of mathematical physics and related questions in the theory of functions, 7. Zap. Naucn. Sem. Leningrad. Otdel. Mat. Inst. Steklov. (LOMI) 38:46–93 (in Russian)

- Lin C-S, Ni W-M, Takagi I. Large amplitude stationary solutions to a chemotaxis system. J Differ Equ. 1988;72:1–27. doi: 10.1016/0022-0396(88)90147-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marciniak-Czochra A. Receptor-based models with diffusion-driven instability for pattern formation in Hydra. J Biol Sys. 2003;11:293–324. doi: 10.1142/S0218339003000889. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marciniak-Czochra A. Strong two-scale convergence and corrector result for the receptor-based model of the intercellular communication. IMA J Appl Math. 2012;77:855–868. doi: 10.1093/imamat/hxs052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marciniak-Czochra A, Karch G, Suzuki K. Unstable patterns in reaction-diffusion model of early carcinogenesis. J Math Pures Appl. 2013;99:509–543. doi: 10.1016/j.matpur.2012.09.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marciniak-Czochra A, Kimmel M. Dynamics of growth and signaling along linear and surface structures in very early tumors. Comput Math Methods Med. 2006;7:189–213. doi: 10.1080/10273660600969091. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marciniak-Czochra A, Kimmel M. Modelling of early lung cancer progression: influence of growth factor production and cooperation between partially transformed cells. Math Models Methods Appl Sci. 2007;17(suppl.):1693–1719. doi: 10.1142/S0218202507002443. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marciniak-Czochra A, Kimmel M. Reaction-diffusion model of early carcinogenesis: the effects of influx of mutated cells. Math Model Nat Phenom. 2008;3:90–114. doi: 10.1051/mmnp:2008043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marciniak-Czochra A, Nakayama M, Takagi I. Pattern formation in a diffusion-ODE model with hysteresis. Differ Intergr Eqn. 2015;28(7–8):655–694. [Google Scholar]

- Marciniak-Czochra A, Ptashnyk M. Derivation of a macroscopic receptor-based model using homogenisation techniques. SIAM J Mat Anal. 2008;40:215–237. doi: 10.1137/050645269. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mimura M, Tabata M, Hosono Y. Multiple solutions of two-point boundary value problems of Neumann type with a small parameter. SIAM J Math Anal. 1980;11:613–631. doi: 10.1137/0511057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mulone G, Solonnikov VA. Linearization principle for a system of equations of mixed type. Nonlinear Anal. 2009;71(3–4):1019–1031. doi: 10.1016/j.na.2008.11.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murray JD. Mathematical biology. I. An introduction. Interdisciplinary applied mathematics. 3. New York: Springer; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Murray JD. Mathematical biology. II. Spatial models and biomedical applications. Interdisciplinary applied mathematics. 3. New York: Springer; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ni W-M. Qualitative properties of solutions to elliptic problems. In: Chipot M, Quittner P, editors. Handbook of differential equations: stationary partial differential equations 1. Amsterdam: North-Holland; 2004. pp. 157–233. [Google Scholar]

- Ni W-M, Takagi I. On the shape of least energy solution to a semilinear Neumann problem. Commn Pure Appl Math. 1991;44:819–851. doi: 10.1002/cpa.3160440705. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ni W-M, Takagi I. Locating the peaks of least-energy solutions to a semilinear neumann problem. Duke Math J. 1993;70:247–281. doi: 10.1215/S0012-7094-93-07004-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pham K, Chauviere A, Hatzikirou H, Li X, Byrne HM, Cristini V, Lowengrub J. Density-dependent quiescence in glioma invasion: instability in a simple reaction-diffusion model for the migration/proliferation dichotomy. J Biol Dyn. 2011;6:54–71. doi: 10.1080/17513758.2011.590610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter D, Stirling DSG. ntegral equations. A practical treatment, from spectral theory to applications, Cambridge Texts in Applied Mathematics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Reed M, Simon B. Methods of modern mathematical physics. I. Functional analysis. 2. New York: Academic Press Inc.; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Rothe F (1984) Global solutions of reaction-diffusion systems, Lecture Notes in Mathematics, 1072. Springer-Verlag, Berlin

- Sakamoto K. Construction and stability analysis of transition layer solutions in reaction-diffusion systems. Tohoku Math J. 1990;42:17–44. doi: 10.2748/tmj/1178227692. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Satnoianu RA, Menzinger M, Maini PK. Turing instabilities in general systems. J Math Biol. 2000;41:493–512. doi: 10.1007/s002850000056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shatah J, Strauss W (2000) Spectral condition for instability. Nonlinear PDE’s, dynamics and continuum physics (South Hadley, MA, 1998), 189–198, Contemp. Math., 255, Am Math Soc, Providence, RI

- Suzuki K. Mechanism generating spatial patterns in reaction-diffusion systems. Interdiscip Inf Sci. 2011;17:131–153. [Google Scholar]

- Smoller J. Shock waves and reaction-diffusion equations, Grundlehren der Mathematischen Wissenschaften. 2. New York: Springer; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Turing AM. The chemical basis of morphogenesis. Phil Trans R Soc B. 1952;237:37–72. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1952.0012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Umulis DM, Serpe M, O’Connor MB, Othmer HG. Robust, bistable patterning of the dorsal surface of the Drosophila embryo. PNAS. 2006;103:11613–11618. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510398103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Shao H, Wu Y. Stability of travelling front solutions for a forest dynamical system with cross-diffusion. IMA J Appl Math. 2013;78:494–512. doi: 10.1093/imamat/hxr063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wei J (2008) Existence and stability of spikes for the Gierer-Meinhardt system. Handbook of differential equations: stationary partial differential equations. Vol. V, 487–585, Handb. Differ. Equ., Elsevier/North-Holland, Amsterdam

- Wei J, Winter M. Existence, classification and stability analysis of multiple-peaked solutions for the Gierer-Meinhardt system in . Methods Appl Anal. 2007;14:119–163. [Google Scholar]

- Wei J, Winter M. Stationary multiple spots for reaction-diffusion systems. J Math Biol. 2008;57:53–89. doi: 10.1007/s00285-007-0146-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei J, Winter M. Stationary Stability of cluster solutions in a cooperative consumer chain model. J Math Biol. 2014;68:1–39. doi: 10.1007/s00285-012-0616-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagi A. Abstract parabolic evolution equations and their applications. Springer Monographs in Mathematics. Berlin: Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]