Abstract

Appearance-related pressures have been associated with binge eating in previous studies. Yet, it is unclear if these pressures are associated with emotional eating or if specific sources of pressure are differentially associated with emotional eating. We studied the associations between multiple sources of appearance-related pressures, including pressure to be thin and pressure to increase muscularity, and emotional eating in 300 adolescents (Mage = 15.3, SD = 1.4, 60% female). Controlling for age, race, puberty, body mass index (BMI) z-score, and sex, both pressure to be thin and pressure to be more muscular from same-sex peers were positively associated with emotional eating in response to feeling angry/frustrated and unsettled (ps<.05). Pressure from same-sex peers to be more muscular also was associated with eating when depressed (p<.05), and muscularity pressure from opposite-sex peers related to eating in response to anger/frustration (p<.05). All associations were fully mediated by internalization of appearance ideals according to Western cultural standards (ps<.001). Associations of pressures from mothers and fathers with emotional eating were non-significant. Results considering sex as a moderator of the associations between appearance-related pressures and emotional eating were non-significant. Findings illustrate that both pressure to be thin and muscular from peers are related to more frequent emotional eating among both boys and girls, and these associations are explained through internalization of appearance-related ideals.

Keywords: emotional eating, pressure to be thin, pressure to be muscular, internalization of appearance ideals, adolescents

1. Introduction

Disinhibited eating is defined as episodes of overeating resulting from a lack of self-regulation (Vannucci et al., 2013). Emotional eating is a distinct type of disinhibited eating that is defined as the consumption of food in response to negative affect (Faith, Allison, & Geliebter, 1997). Emotional eating has been associated with excessive body weight (Braet et al., 2008), depressive symptoms (Przybylowicz, Jesiolowska, Obara-Golebiowska, & Anotniak, 2014), and general disordered eating pathology (Goosens, Braet, & Decaluwe, 2007). Although emotional eating demonstrates significant overlap with other forms of overeating, particularly binge eating, the two behaviors reflect unique disinhibited eating phenotypes (Tanofsky-Kraff et al., 2007; Vannucci et al., 2013). For instance, emotional eating is more prevalent than binge eating in adolescents (Shomaker, Tanofsky-Kraff, & Yanovski, 2010), and it has been shown to be an antecedent of binge eating (Zeeck, Stelzer, Woolfgang Linster, Joos, & Hartmann, 2010). Thus, identifying individual factors that are associated with, and may contribute to, emotional eating is important when considering the development of this eating behavior specifically, as well as for the worsening of disinhibited eating pathology more broadly.

One factor that may contribute to emotional eating is sociocultural pressure regarding appearance. In Western cultures, a lean body type is considered ideal (Smolak & Murnen, 2008), with some sex-based variations in the socially-prescribed ideal. Specifically, some data suggest that girls prefer an ultra thin body type (Ahern, Bennet, & Hetherington, 2008; Stice, 2001), while boys prefer a lean, muscular body (Hargreaves & Tiggemann, 2004). More contemporary data indicate that sex-based variations in appearance ideals may be less distinct. Indeed, a considerable number of girls report a preference for a muscular body shape (Slater & Tiggemann, 2011), and some boys report aspiring to a thin ideal (Schaefer et al., 2015). Among both boys and girls, there is agreement that having overweight or obesity is far from ideal. In fact, these physical attributes are highly stigmatized and associated with an array of negative qualities including laziness, low intelligence, and poor social skills (Lynagh et al., 2015). A large percentage of adolescents report experiencing consistent and overt messages regarding lean appearance-related ideals in the form of habitual weight-related teasing (Neumark-Sztainer et al., 2002); receipt of these messages, in turn, is associated with greater binge eating (Lieberman, Gauvin, Bukowski, & White, 2001) and bulimic pathology among boys and girls (Eisenberg, Berg, & Neumark-Sztainer, 2012). Similarly, in a sample of adolescent boys, perceived pressures to lose weight were associated with greater eating pathology, including restrictive and binge eating practices (Rodgers, Ganchou, Franko, & Chabrol, 2012). In this sample, both a desire to obtain a thinner body and a desire to have a more muscular body were associated with greater eating pathology. Data suggest that, for both boys and girls, adolescence may be a particularly vulnerable period for increased appearance-related social pressures (Helfert & Waschburger, 2013) and for the development of disinhibited eating patterns (Swanson, Crow, Le Grange, Swendsen, & Merikangas, 2011), like emotional eating (Bennett, Greene, & Schwartz-Barcott, 2013). However, no studies have examined the link between appearance-related pressures and emotional eating.

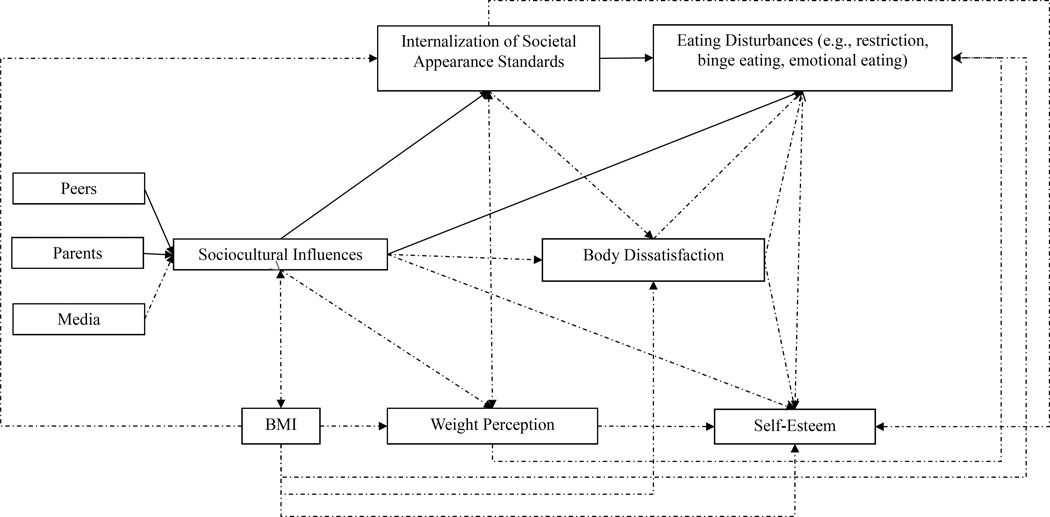

The Tripartite Influence Model (Thompson, Heinberg, Altabe, & Tantleff-Dunn, 1999) (Figure 1) suggests that influences from parents, peers, and the media lead to eating disturbances, including disinhibited or binge-like eating, through internalization of societal standards of appearance. According to the model, pressure from external sources promotes the cognitive internalization of a standard for physical attractiveness, which then leads to eating disturbances in an effort to change one’s shape or weight. Although the Tripartite Influence Model has been examined in the context of binge eating (Yamamiya, Shroff, & Thompson, 2008), no studies have examined the validity of this model in relation to emotional eating. Similarly, no studies have determined whether different sources of interpersonal pressures regarding appearance-related ideals, including from fathers, mothers, same-sex or opposite-sex peers, demonstrate unique associations with emotional eating. Extant data indicate that there may be important differences to investigate. Pressure to be thin from peers, for instance, is more strongly correlated with bulimic behavior among females (Young, Clopton, & Bleckley, 2004), while pressure from fathers to not be fat was more likely to predict binge eating in boys (Field et al., 2008).

Figure 1.

The Tripartite Influence Model adapted from Papp, Urban, Czegledi, Babusa, and Tury (2012).

The primary aim of the current study was to examine the associations between different sources of appearance-related pressure, including both pressure to be thin and pressure to be muscular, and emotional eating among adolescent boys and girls. We hypothesized that these appearance-related pressures would be positively associated with emotional eating. Based on past research investigating pressure related to thinness (Phares, Steinberg, & Thompson, 2004), we further anticipated that appearance-related pressure from peers would be more strongly associated with emotional eating in girls, whereas pressure from parents would be more strongly associated with emotional eating among boys. Interactions with weight status were also examined, as prior data indicate that the association between appearance-related pressure and disinhibited eating may be particularly strong among youth with overweight (Neumark-Sztainer et al., 2002). The second aim of the current study was to explore the pathway connecting pressure to be thin with emotional eating in the context of the Tripartite Influence Model (Thompson et al., 1999) (Figure 1). We hypothesized that internalization of appearance ideals would mediate the relationship between pressure to be thin and emotional eating among both boys and girls.

2. Methods

2.1.Participants and Procedures

Participants were adolescent (13–17y) boys and girls volunteering to take part in a non-treatment study of eating behaviors in adolescence (ClinicalTrials.Gov ID: NCT00631644). The current paper is a secondary analysis; previous reports provide full inclusion and exclusion criteria and detailed methodological descriptions (Shomaker et al., 2010). Participants of all weight strata who did not have significant medical or psychological disorders were recruited from Maryland, the District of Columbia, and Virginia by advertisements. Parental guardians provided written consent, and adolescents provided written assent for participation in the study. The Institutional Review Board of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development approved the study protocol and all procedures. Adolescents received financial compensation for their time and the inconvenience of participating in the study.

All participants completed a half-day visit, during which data were evaluated at an outpatient pediatric clinic at the National Institutes of Health Clinical Research Center. Participants observed an overnight fast beginning at 10:00 pm the night before their visit. At approximately 10:00 am the morning of the appointment, they received a standardized breakfast shake after all fasting body composition measurements were assessed. Questionnaires were completed in a sated state, following the liquid breakfast.

Body Mass Index (BMI)

Height was calculated as the average of three measurements collected to the nearest millimeter with a calibrated stadiometer. Weight was measured in a fasted state to the nearest 0.1 kg with a calibrated digital scale.

Puberty

During a physical examination, an endocrinologist or nurse practitioner measured testicular volume in boys using a set of orchidometer beads (Marshall & Tanner, 1970) and breast development in girls according to the five stages of Tanner (Marshall & Tanner, 1969). These data were used to categorize adolescents into the following groups: pre-puberty (Tanner stage 1; testis volumes < 4 ml), early puberty (stage 2; testis volumes 4 – 10 ml), mid-puberty (stage 3; testis volumes 10 – 14 ml), late puberty (stage 4; testis volumes 14 – 20 ml), or adult standard (stage 5; testis volumes > 20 ml).

2.2.Psychological Assessments

Pressure to be Physically Attractive Questionnaire; Pressure to be Thin and Pressure to be Muscular subscales (PPAQ-THIN; PPAQ-MUSC) (Shomaker & Furman, 2009)

Items on the PPAQ-THIN (e.g., This person compliments me when I look thin) and PPAQ-MUSC (e.g., This person compliments me when I look built or toned) assess how often the participant experiences pressure to be thin and pressure to be muscular from different sources, including fathers, mothers, same-sex peers, opposite-sex peers, and romantic partners. All items are rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (almost always) and mean scores are calculated for each of the five sources of pressure. Because only 37% of participants identified a current romantic partner, items assessing pressure from this source were not analyzed. The PPAQ-THIN has demonstrated good internal reliability (αs > .75) and acceptable convergent validity with the Perceived Sociocultural Pressure Scale (Shomaker & Furman, 2009; Stice, Nemeroff, & Shaw, 1996). The PPAQ-MUSC has also demonstrated excellent internal reliability (αs > .90) and predictive validity for pursuit of muscularity (Shomaker & Furman, 2010). In the current study, internal reliability coefficients for the PPAQ-THIN and PPAQ-MUSC subscales were acceptable (αs = .81–.87).

The Emotional Eating Scale for Children and Adolescents (EES-C) (Tanofsky-Kraff et al., 2007)

The EES-C is a 25-item questionnaire used to measure youth’s tendency to cope with various negative affective states by eating (Tanofsky-Kraff et al., 2007). Each item is scored on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (I have no desire to eat) to 5 (I have a very strong desire to eat). The EES-C includes three subscales, eating in response to feeling: 1) angry/frustrated; 2) depressed; and 3) unsettled subscales. All subscales have demonstrated good internal consistency and 3-month test-retest reliability in children and adolescents (Tanofsky-Kraff et al., 2007). The internal reliability coefficients for the current sample were acceptable (αs = .80 – .93).

Sociocultural Attitudes Towards Appearance Scale-3 (SATAQ-3) (Thompson, van den Berg, Roehrig, Guarda, & Heinberg, 2004)

The SATAQ-3 assesses perceptions regarding societal influences on appearance, including messages and information received from the media. Internalization of appearance ideals was assessed with the 9-item General Internalization subscale (e.g., I wish I looked like the models in music videos). Each item on the General Internalization subscale is scored on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree) and total scores represent an average of these items. This subscale has demonstrated excellent convergent validity with measures of body image (Thompson et al., 2004). The internal reliability coefficient for the general internalization factor was excellent (α = .93) for the current sample.

2.3.Data Analytic Plan

Extreme, but plausible, outliers were recoded to fall 1.5 times the interquartile range below or above the 25th or 75th percentile so that they were no longer outliers (Behrens, 1997). This procedure places the outliers in the lower or upper 1–2% of the distribution, thereby minimizing outliers’ influence on the characteristics of the distribution (Behrens, 1997). No more than 3% of the data comprising any variable was considered an outlier. After adjusting outliers, skew and kurtosis were confirmed to be satisfactory for all variables. Independent samples t-tests, chi-square analyses, and a non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test were conducted to compare our final sample to those excluded due to missing data (8–13% of participants per variable). The same statistical analyses were used to compare boys and girls on all variables of interest. Unadjusted correlation analyses were conducted to evaluate the associations among various sources of appearance-related pressures, internalization of appearance ideals, and emotional eating separately by sex. Hierarchical multiple regression models were used to evaluate our primary hypotheses. Covariates were entered into the first level of each model, including age (y), race (0 = non-Hispanic White, 1 = other), puberty, and BMI z-score. Level two of each model contained all primary independent variables, including sources of appearance-related pressures and sex (coded 0 = male, 1 = female). Level three of each model contained the two-way interaction term between each source of appearance-related pressures and sex. Three-way interactions between each source of appearance-related pressures, sex, and weight status (coded: 0 = non-overweight, BMI < 25, or 1 = overweight, BMI ≥ 25) (Kuczmarski et al., 2000) were also considered, and added to level four of each model. For analyses including weight status, BMI z-score was removed as a covariate. Because the four sources of pressure to be thin or muscular were moderately to highly correlated with each other (rs = .63–.90 for pressure to be thin and rs = .55–.74 for pressure to be muscular), separate models were conducted for each source of pressure. Dependent variables included the three emotional eating subscales: angry/frustrated, depressive symptoms, and unsettled feelings. For all analyses, if interaction effects were significant, additional follow-up models were conducted for the appropriate subgroups to evaluate the main effects of appearance-related pressures on emotional eating. To address the second aim, the Indirect macro created by Preacher and Hayes (2008) for SPSS (IBM Corp, 2010), which includes bootstrapping of indirect effects with 5000 resamples and bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals, was used to evaluate whether internalization of appearance ideals mediated the association between appearance-related pressures and emotional eating. We examined mediation by calculating the significance of direct and indirect effects through multiple regression analyses. Mediation models were only conducted if the hierarchical regression model for the total effect was significant while controlling for all relevant covariates. Separate models were run for each different source of pressure to be thin. To minimize concerns related to multicollinearity, all PPAQ-THIN and PPAQ-MUSC subscale scores were centered based on the grand mean (Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken, 2003). Main and interaction effects were considered significant if p values were < .05. All tests were two-tailed. All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics version 19 (IBM Corp, 2010).

3. Results

Three-hundred adolescents (Mage = 15.3, SD = 1.4, 60% girls) participated in the current study. Descriptive data for demographic, anthropometric, and psychological variables for the total sample and by sex are presented in Table 1. Unadjusted bivariate correlations evaluating the associations between various sources of pressure to be thin, pressure to be muscular, and each indicator of disinhibited eating for boys and girls are summarized in Table 2.

Table 1.

Characteristics for the total sample, girls, and boys

| Total Sample (N = 300) | Girls (n = 180) | Boys (n = 120) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | M | SD | Mdn | % | M | SD | Mdn | % | M | SD | Mdn | % | p |

| Age (y) | 15.0 | 1.4 | 15.4 | 1.4 | 15.0 | 1.3 | 0.1 | ||||||

| Race | 0.5 | ||||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 39.0 | 44.2 | 32.7 | 0.02 | |||||||||

| African American | 32.0 | 32.8 | 30.8 | 0.7 | |||||||||

| Asian | 6.3 | 5.0 | 8.3 | 0.3 | |||||||||

| Multiple | 4.7 | 5.6 | 3.3 | 0.4 | |||||||||

| Puberty | 4.0 | 5.0 | 4.0 | 0.003 | |||||||||

| BMIz | 0.6 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.9 | <0.001 | ||||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.0 | 7.1 | 26.3 | 8.2 | 22.0 | 4.0 | 0.001 | ||||||

| Overweight /obesitya | 15.7/16.7 | 14.4/25.0 | 17.5/4.2 | 0.001 | |||||||||

| Emotional eating | |||||||||||||

| Angry/frustrated | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.4 | ||||||

| Depressed | 1.0 | 0.8 | 1.2 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.8 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Unsettled | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.98 | ||||||

| Internalization of ideals | 2.6 | 1.1 | 2.7 | 1.2 | 2.4 | 1.0 | 0.005 | ||||||

| Pressure to be thin | |||||||||||||

| From fathers | 1.9 | 1.1 | 2.0 | 1.2 | 1.8 | 1.0 | 0.2 | ||||||

| From mothers | 2.4 | 1.3 | 2.7 | 1.4 | 2.0 | 1.0 | <0.001 | ||||||

| From same-sex peers | 2.2 | 1.2 | 2.6 | 1.2 | 1.6 | 0.9 | <0.001 | ||||||

| From opposite-sex peers | 1.9 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 1.1 | 1.8 | 1.0 | 0.1 | ||||||

| Pressure to be muscular | |||||||||||||

| From fathers | 2.2 | 1.1 | 2.0 | 1.1 | 2.4 | 1.2 | 0.002 | ||||||

| From mothers | 2.4 | 1.2 | 2.3 | 1.2 | 2.5 | 1.2 | 0.2 | ||||||

| From same-sex peers | 2.1 | 1.1 | 2.1 | 1.1 | 2.2 | 1.0 | 0.7 | ||||||

| From opposite-sex peers | 2.1 | 1.1 | 1.9 | 1.0 | 2.5 | 1.2 | <0.001 | ||||||

Overweight is defined as a BMI at or above the 85th percentile; obesity is defined as a BMI at or above the 95th percentile

Note. M = mean; SD = standard deviation, Mdn = median; BMIz = body mass index z-score

Table 2.

Unadjusted correlations among emotional eating subscales, sources of appearance-related pressures, and appearance-related internalization for boys and girls

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Emotional eating-angry/frustrated | - | .70*** | .79*** | −.10 | .06 | .07 | −.10 | −.01 | .08 | .16* | .02 | .25** |

| 2. | Emotional eating-depressed | .78*** | - | .69*** | −.16* | .06 | .07 | −.11 | −.05 | .09 | .15* | −.04 | .34*** |

| 3. | Emotional eating-unsettled | .82*** | .76*** | - | −.10 | .04 | .10 | −.05 | −.01 | .07 | .18* | −.01 | .25** |

| 4. | Thin pressure from fathers | .16 | .17 | .18 | - | .63*** | .57*** | .63*** | .77*** | .54*** | .44*** | .56*** | .16* |

| 5. | Thin pressure from mothers | .09 | .08 | .14 | .90*** | - | .69*** | .63*** | .48*** | .66*** | .51*** | .50*** | .26** |

| 6. | Thin pressure from same-sex peers | .20* | .07 | .16 | .63*** | .64*** | - | .65*** | .49*** | .54*** | .68*** | .59*** | .27*** |

| 7. | Thin pressure from opposite-sex peers | .12 | .11 | .13 | .69*** | .71*** | .78*** | - | .51*** | .55*** | .58*** | .73*** | .24** |

| 8. | Muscular pressure from fathers | .21* | .20* | .21* | .72*** | .65*** | .47*** | .51*** | - | .72*** | .61*** | .62*** | .24** |

| 9. | Muscular pressure from mothers | .17 | .13 | .14 | .61*** | .68*** | .42*** | .54*** | .77*** | - | .77*** | .66*** | .26** |

| 10. | Muscular pressure from same-sex peers | .14 | .05 | .05 | .31** | .31** | .66*** | .49*** | .54*** | .43*** | - | .78*** | .25** |

| 11. | Muscular pressure from opposite-sex peers | .25* | .16 | .19* | .32** | .32** | .47*** | .62*** | .45*** | .51*** | .61*** | - | .19* |

| 12. | Internalization of appearance ideals | .21*** | .29*** | .20** | .15* | .26*** | .31*** | .25*** | .19* | .16 | .39*** | .34*** | - |

Note. Correlations in boys are presented below the diagonal (n = 120); correlations in girls are presented above the diagonal (n = 180);

p < .001;

p < .01;

p < .05

3.1.Pressure to be Thin and Emotional Eating

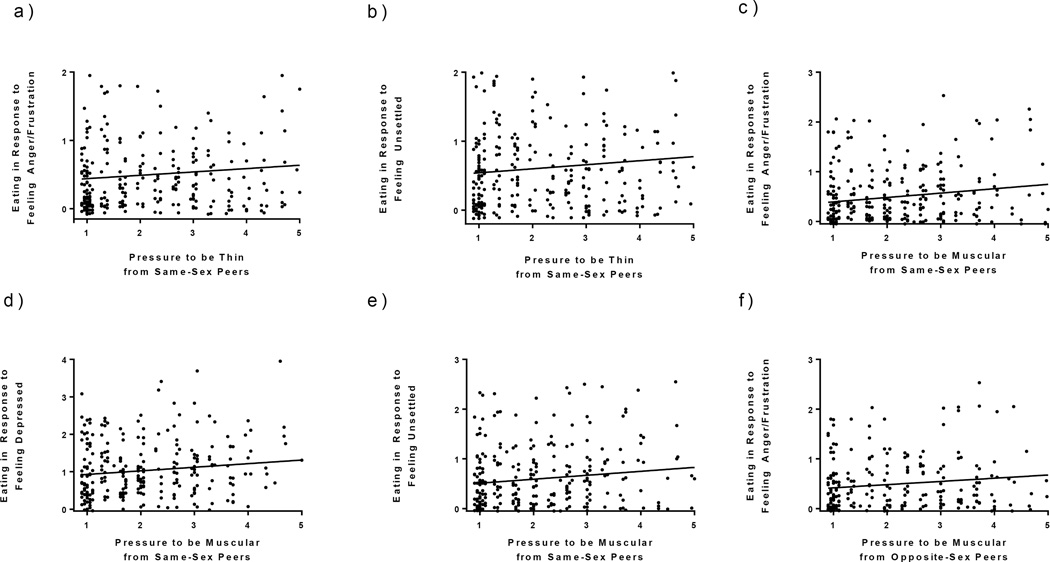

Results from hierarchical regression models examining the main and interaction effects for pressure to be thin and sex on each of the three domains of emotional eating are summarized in Table 3. Unstandardized regression coefficients are presented (β). After controlling for age, race, puberty, and BMI z-score, there were significant, positive main effects for pressure to be thin from same-sex peers on participants’ emotional eating in response to feeling angry/frustrated (Figure 2a; β = .07, p = .03) and in response to feeling unsettled (Figure 2b; β = .09, p = .02). Main effects for all other sources of pressure and emotional eating were non-significant (ps = .19–.97).

Table 3.

Multiple hierarchical regressions reporting associations between pressure to be thin from fathers, mothers, same- and opposite-sex peers, and sex for adolescents’ emotional eating

| Angry/Frustrated | Depression | Unsettled | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level | Entered | βa | SE | bb | R2 | ΔR2 | βa | SE | bb | R2 | ΔR2 | βa | SE | bb | R2 | ΔR2 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||

| Age | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.19** | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.11 | |||||||

| Race | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.001 | −0.06 | 0.13 | −0.03 | 0.01 | 0.11 | 0.003 | |||||||

| Puberty | −0.03 | 0.05 | −0.04 | −0.04 | 0.07 | −0.05 | 0.003 | 0.06 | 0.004 | |||||||

| BMIz | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.05 | 0.22 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.03 | |||||||

| 2a | 0 | 0 | 0.06** | 0.04** | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||

| FTHIN | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.02 | −0.05 | 0.05 | −0.06 | −0.01 | 0.04 | −0.02 | |||||||

| Sex | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.8 | 0.38 | 0.1 | 0.28 | 0.001 | 0.08 | 0.03 | |||||||

| 2b | 0.00*** | 0 | 0.07 | 0.04*** | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||

| MTHIN | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.09 | |||||||

| Sex | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.20** | −0.04 | 0.08 | −0.03 | |||||||

| 2c | 0.001*** | 0.001 | 0.07** | 0.05** | 0.01 | 0.01 | ||||||||||

| SPTHIN | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.15* | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.1 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.15* | |||||||

| Sex | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.30** | 0.11 | 0.18** | −0.09 | 0.09 | −0.07 | |||||||

| 2d | 0 | 0 | 0.05* | 0.04** | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||

| OPTHIN | 0.004 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.002 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.04 | |||||||

| Sex | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.36 | 0.11 | 0.22** | −0.03 | 0.09 | −0.03 | |||||||

| 3a | 0 | 0 | 0.08*** | 0.02* | 0.001 | 0.001* | ||||||||||

| FTHIN × Sex |

0.13 | 0.07 | 0.2 | 0.22 | 0.1 | 0.24* | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.20* | |||||||

| 3b | 0.00*** | 0 | 0.07 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||

| MTHIN × Sex |

0.01 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.001 | 0.09 | 0.001 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.08 | |||||||

| 3c | 0.01 | 0.009 | 0.06** | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0 | ||||||||||

| SPTHIN × Sex |

0.1 | 0.07 | 0.19 | 0.03 | 0.1 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.08 | |||||||

| 3d | 0 | 0 | 0.05** | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||

| OPTHIN × Sex |

0.11 | 0.07 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.1 | 0.18 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.13 | |||||||

Note. FTHIN = pressure to be thin from adolescent’s father; MTHIN = pressure to be thin from adolescent’s mother; SPTHIN = pressure to be thin from adolescent’s same-sex peers; OPTHIN = pressure to be thin from adolescent’s opposite-sex peers;

p < .001;

p < .01;

p < .05

β = unstandardized regression coefficient at each step.

b = standardized regression coefficient at each step.

R2 = adjusted proportion of variability in the dependent variable accounted for by model.

ΔR2 = change in the adjusted proportion of variability in the dependent variable accounted for by model.

Figure 2.

After controlling for age, race, puberty, BMI z-score, and sex, pressure to be thin from same-sex peers was positively associated with emotional eating in response to feeling (a) angry/frustrated (β = .07, p = .03) and (b) unsettled (β = .09, p = .02). Pressure to be muscular from same-sex peers was positively associated with emotional eating in response to feeling (c) angry/frustrated (β = .09, p = .005), (d) depressed (β = .10, p = .03), and (e) unsettled (β = .08, p = .02). Pressure to be muscular from opposite-sex peers was positively associated with emotional eating in response to feeling (f) angry/frustrated (β = .08, p = .03).

Analyses of two-way interactions between sources of pressure to be thin and sex revealed a significant interaction between pressure from fathers and sex for emotional eating in response to feeling depressed (β = .22, p = .03) and emotional eating in response to feeling unsettled (β = .15, p = .049). However, upon stratification by sex, associations between pressure from fathers and emotional eating were non-significant for girls (β = −.07 to −.11, ps > .08), as well as boys (β = .13 to .14, ps > .06). Unstandardized betas were suggestive of an inverse trend between pressure from fathers and emotional eating among girls and a positive trend between these variables among boys. No other interactions between any source of pressure to be thin and sex were significant (ps = .07–.99).

Three-way interactions between source of appearance-related pressure, sex, and weight status were evaluated, however results indicated no significant interactions. All two-way interactions between source of pressure and weight status were also non-significant. Therefore, these data are not shown.

3.2.Pressure to be Muscular and Emotional Eating

Results from hierarchical regression models examining the main and interaction effects for pressure to be muscular and sex on each of the three domains of emotional eating are summarized in Table 4. After controlling for age, race, puberty, and BMI z-score, there were significant, positive main effects for pressure to be muscular from same-sex peers on adolescents’ emotional eating in response to feeling angry/frustrated (Figure 2c; β = .09, p = .005), eating in response to feeling depressed (Figure 2d; β = .10, p = .03), and eating in response to feeling unsettled (Figure 2e; β = .08, p = .02). Further, there were significant and positive main effects for pressure to be muscular from opposite-sex peers on emotional eating in response to feeling angry/frustrated (Figure 2f; β = .08, p = .03). Main effects for all other sources of pressure and emotional eating were non-significant (ps = .06–.54).

Table 4.

Multiple hierarchical regressions reporting associations between pressure to be muscular from fathers, mothers, same- and opposite-sex peers, and sex for adolescents’ emotional eating

| Angry/Frustrated | Depression | Unsettled | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level | Entered | βa | SE | bb | R2 | ΔR2 | βa | SE | bb | R2 | ΔR2 | βa | SE | bb | R2 | ΔR2 |

| 1 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.06** | 0.08** | −0.01 | 0.01 | ||||||||||

| Age | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.19 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.11 | |||||||

| Race | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.00 | −0.06 | 0.13 | −0.03 | 0.01 | 0.11 | 0.00 | |||||||

| Puberty | −0.03 | 0.05 | −0.04 | −0.04 | 0.07 | −0.05 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.01 | |||||||

| BMIz | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.03 | −0.02 | 0.05 | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.03 | |||||||

| 2a | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.00 | ||||||||||

| FMUSC | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.07 | |||||||

| Sex | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.39 | 0.11 | 0.23*** | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.01 | |||||||

| 2b | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.08 | .01*** | 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||||||||

| MMUSC | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.10 | |||||||

| Sex | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.39 | 0.10 | 0.24*** | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.00 | |||||||

| 2c | 0.01 | .03** | 0.07 | .02* | 0.01 | .02* | ||||||||||

| SPMUSC | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.17** | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.13* | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.14* | |||||||

| Sex | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.37 | 0.10 | 0.22*** | −0.01 | 0.08 | −0.01 | |||||||

| 2d | 0.00 | .02* | 0.05 | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.01 | ||||||||||

| OPMUSC | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.16* | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.10 | |||||||

| Sex | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.16 | 0.38 | 0.11 | 0.23** | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.00 | |||||||

| 3a | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||||||||

| FMUSC × Sex |

−0.12 | 0.06 | −0.28 | −0.16 | 0.09 | −0.25 | −0.12 | 0.07 | −0.25 | |||||||

| 3b | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||||||||

| MMUSC × Sex |

−0.05 | 0.06 | −0.12 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.00 | −0.02 | 0.07 | −0.05 | |||||||

| 3c | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.00 | ||||||||||

| SMUSC × Sex |

−0.03 | 0.06 | −0.07 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.12 | |||||||

| 3d | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.01 | ||||||||||

| OMUSC × Sex |

0.07 | 0.07 | 0.14 | −0.12 | 0.07 | −0.25 | −0.14 | 0.10 | −0.21 | |||||||

Note. FMUSC = pressure to be muscular from adolescent’s father; MMUSC = pressure to be muscular from adolescent’s mother; SMUSC = pressure to be muscular from adolescent’s same-sex peers; OPMUSC = pressure to be muscular from adolescent’s opposite-sex peers;

p < .001;

p < .01;

p < .05

β = unstandardized regression coefficient at each step.

b = standardized regression coefficient at each step.

R2 = adjusted proportion of variability in the dependent variable accounted for by model.

ΔR2 = change in the adjusted proportion of variability in the dependent variable accounted for by model.

Analyses of two-way interactions between sources of pressure to be muscular and sex revealed no significant results (ps = .06–.99). Three-way interactions between source of appearance-related pressure, sex, and weight status were evaluated; results indicated no significant interactions. All two-way interactions between pressure to be muscular and weight status were also non-significant. Therefore, these data are not shown.

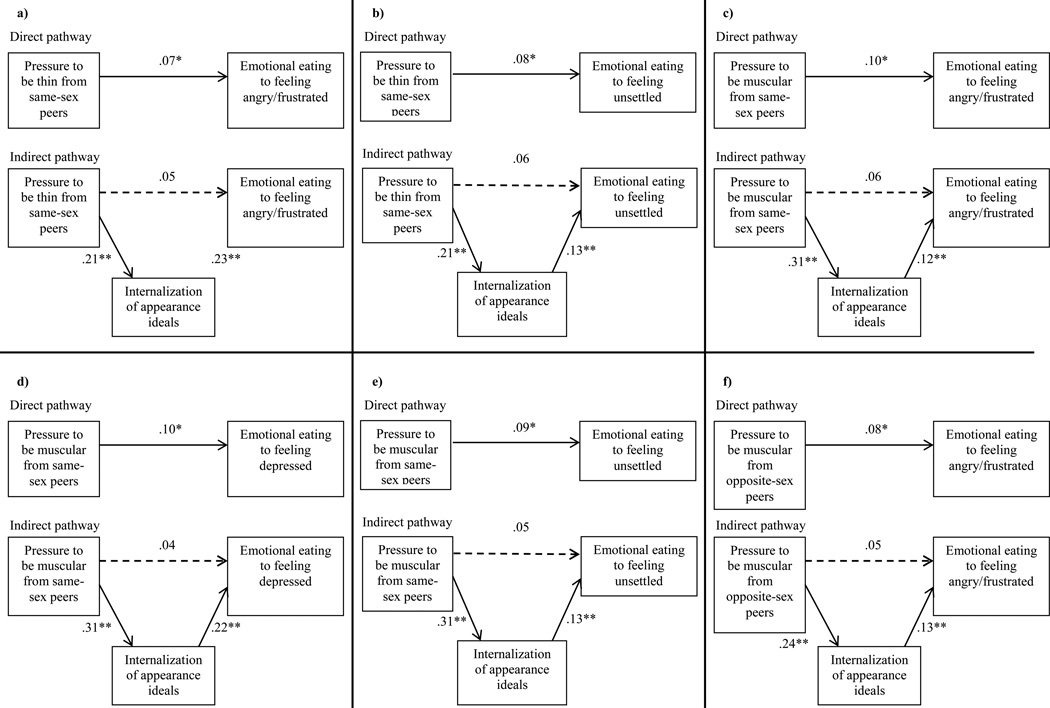

3.3.Mediation of Internalization of Appearance Ideals

Results from significant mediation models are presented in Figures 3a–f. We present mediation results for pressure from same-sex and opposite-sex peers, as these were the only sources of appearance-related pressure to demonstrate a significant main effect on emotional eating. Results indicated that internalization of appearance ideals fully mediated the associations of pressure to be thin from same-sex peers with emotional eating in response to feeling angry/frustrated (Figure 3a; SE = .03; 95% CI: .01, .05; R2Adjusted = .06; p = .003) and to feeling unsettled (Figure 3b; SE = .04; 95% CI: .01, .06; R2Adjusted = .05; p = .004). Additionally, internalization of appearance ideals fully mediated the associations of pressure to be muscular from same-sex peers with emotional eating in response to feeling angry/frustrated (Figure 3c; SE = .03; 95% CI: .01, .06; R2Adjusted = .06; p = .002), feeling depressed (Figure 3d; SE = .05; 95% CI: .04, .11; R2Adjusted = .15; p < .000), and feeling unsettled (Figure 3e; SE = .04; 95% CI: .02, .07; R2Adjusted = .07; p = .005). In addition, internalization of appearance ideals fully mediated the association between pressure to be muscular from opposite-sex peers and emotional eating in response to feeling angry/frustrated (Figure 3f; SE = .03; 95% CI: .03, .06; R2Adjusted = .05; p = .009). Furthermore, when internalization of appearance ideals was added to each model, main effects between all appearance-related pressures and emotional eating became non-significant (ps = .06–.39), suggesting that internalization of Western cultural standards for physical attractiveness fully mediated the associations of appearance-related peer pressure and emotional eating.

Figure 3.

Standardized regression coefficients for: the relationships of pressure from same-sex peers to be thin with (a) emotional eating in response to feeling angry/frustrated and (b) emotional eating in response to feeling unsettled, as mediated by internalization of appearance ideals; also for the relationships of pressure to be muscular from same-sex peers with (c) emotional eating in response to feeling angry/frustrated, (d) emotional eating in response to feeling depressed, and (e) emotional eating in response to feeling unsettled, as mediated by internalization of appearance ideals; and for the relationship of pressure to be muscular from opposite-sex peers with (f) emotional eating in response to feeling angry/frustrated, as mediated by internalization of appearance ideals. *p < .05, **p < .001

4. Discussion

In the current study, we evaluated the associations among appearance-related pressures, internalization of appearance ideals, and emotional eating in adolescent boys and girls. Data suggested that both pressure to be thin and pressure to be muscular from same-sex peers was positively associated with emotional eating in response to feeling both angry/frustrated and unsettled. Further, pressure to be muscular from opposite-sex peers was related to more frequent emotional eating in response to feeling angry/frustrated. Girls reported perceiving significantly more pressure to be thin from their same-sex peers relative to boys, and conversely, boys reported more pressure to be muscular from opposite-sex peers relative to girls. Despite these mean-level differences, sex did not moderate the associations among pressures, appearance-related internalization, and emotional eating. Internalization of appearance-related ideals did mediate these associations, suggesting that the relationship between appearance-related pressures from peers and emotional eating may be explained through these variables’ relationships with internalization of culturally prescribed body image ideals. Data from the current study extend previous research (Yamamiya et al., 2008) by identifying links between specific sources of appearance-related pressures, internalization of appearance ideals, and emotional eating.

It is notable that sex did not moderate either the association between the relationship source of pressure to be thin and emotional eating or the relationship source of pressure to be muscular and emotional eating, as some prior research would suggest (Field et al., 2008; Slater & Tiggemann, 2011). One possibility is that youth in the current study were substantially older (Mage 15.2y) than youth in past research (Mage 11.9y) (Field et al., 2008). Adolescence is a critical developmental period for both boys and girls during which peers, relative to parents, become particularly influential in terms of engagement in problematic, unhealthy behaviors (Scalici & Schulz, 2012). Further, susceptibility to peer influence across several domains, including risky health behaviors, peaks during adolescence (Brown, Bakken, Ameringer, & Mahon, 2008). Thus, because our sample only included adolescents, our results may reflect the strong influence of appearance-related pressures from peers, relative to parents, on boys’ and girls’ emotional eating behavior during this developmental period.

Internalization of appearance-related ideals mediated the relationships between appearance-related pressures and emotional eating, which is consistent with prior data examining bulimic symptoms (Stice, Schupak-Neuberg, Shaw, & Stein, 1994). The more adolescents reported experiencing appearance-related pressures from same- and/or opposite-sex peers, the more they internalized Western culturally-prescribed appearance ideals, which, in turn, was associated with more frequent emotional eating. These data offer tentative suggestions for potential clinical interventions focused on reducing emotional eating among youth. For instance, Stice’s (2002) dissonance-based eating disorder prevention program, which aims to reduce internalization of appearance ideals, also may have positive effects on emotional eating. However, and importantly, Stice’s (2002) program has not been tested in boys, nor has its effects on perceived pressure to increase muscularity been examined. In the current study, we evaluated internalization of appearance ideals, broadly, with newer adaptations of this measure allowing for differentiating between internalization of both thin and muscular ideals. Clarifying the specific attitudinal explanatory mechanisms of the associations of appearance-related pressures and emotional eating might enhance the effectiveness of related interventions. Additionally, eating disorder prevention programs typically place the burden of change on adolescents struggling with appearance-related concerns and disinhibited eating. Researchers should also consider developing and examining the efficacy of interventions intended to reduce the broader, sociocultural presence of appearance-related pressures, particularly from peers.

Strengths of the current study include the evaluation of individual sources of appearance-related pressures and the extension of research regarding the Tripartite Influence Model (Thompson et al., 1999) to emotional eating in a relatively large sample of adolescents. Study limitations include the use of self-report questionnaires, which could introduce measurement errors due to recall biases. Additionally, the cross-sectional design of this study limits interpretations about directionality and prospective data are needed to elucidate the temporal associations among the study variables. Naturalistic methods (e.g., ecological momentary assessment) would also help capture potential emotional eating triggers in vivo. Furthermore, the Tripartite Influence Model (Thompson et al., 1999) also proposes social comparison as another factor that might mediate the association between appearance-related pressures and eating disturbances. Although social comparison was not examined in this study, it is important to consider in future research.

In conclusion, internalization of appearance-related ideals mediated the relationship between appearance-related pressures from peers and emotional eating among adolescent boys and girls; longitudinal evaluations are needed to determine if appearance-related pressures are associated with the development or worsening of future disinhibited eating behaviors.

References

- Ahern AL, Bennet KM, Hetherington MM. Internalization of the ultra-thin ideal: Positive implicit associations with underweight fashion models are associated with drive for thinness in young women. Eating Disorders. 2008;16(4):294–307. doi: 10.1080/10640260802115852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens JT. Principles and procedures of exploratory data analysis. Psychological Methods. 1997;2(2):131–160. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett J, Greene G, Schwartz-Barcott D. Perceptions of emotional eating behavior: A qualitative study of college students. Appetite. 2013;60(1):187–192. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2012.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braet C, Claus L, Goosens L, Moens E, Van Vlierberghe L, Soetens B. Differences in eating style between overweight and normal-weight youngsters. Journal of Health Psychology. 2008;13(6):733–743. doi: 10.1177/1359105308093850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown B, Bakken B, Ameringer S, Mahon MD, editors. A comprehensive conceptualization of the peer influence process in adolescence. New York: Guilford; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. 3rd. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg ME, Berg JM, Neumark-Sztainer D. Associations between hrutful weight-related comments by family and significant other adn the development of disordered eating behaviors in young adults. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2012;35(5):500–508. doi: 10.1007/s10865-011-9378-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faith MS, Allison DB, Geliebter A. Emotional eating and obesity: Theoretical considerations and practical recommendations. In: S D, editor. Obesity and weight control: The health professionals guide to understanding and treatment. Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen; 1997. pp. 739–765. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Aranda F, Krug I, Jimenez-Murcia S, Granero R, Nunez A, Penelo E, Treasure J. Male eating disorders and therapy: a controlled pilot study with one year follow-up. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2009;40(3):479–486. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field AE, Javaras KM, Aneja P, Kitos N, Camargo CA, Taylor CB, Laird NM. Family, peer, and media predictors of becoming eating disordered. Archives of Pediatric Adolescent Medicine. 2008;162(6):574–579. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.162.6.574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George M. Making Sense of Muscle: The Body Experiences of Collegiate Women Athletes. Sociological Inquiry. 2005;75(3):317–345. [Google Scholar]

- Goosens L, Braet C, Decaluwe V. Loss of control over eating in obese youngsters. Behavioral Research Therapy. 2007;45(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves DA, Tiggemann M. Idealized media images and adolescent body image: "comparing" boys and girls. Body Image. 2004;1(4):351–361. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helfert S, Waschburger P. The face of appearance-related social pressure: Gender, age and body mass variations in peer and parental pressure during adolescence. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health. 2013;7(16):4–77. doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-7-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 19.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Grummer-Strawn LM, Flegal KM, Guo SS, Wei R, et al. CDC Growth Charts. 314. Untied States: Advance Data; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law C, Peixoto Labre M. Cultural standards of attractiveness: A thirty-year look at changes in male images in magazines. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly. 2002;79(3):697–711. [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman M, Gauvin L, Bukowski WM, White DR. Interpersonal influence and disordered eating behaviors in adolescent girls: The role of peer modeling, social reinforcement, and body-related teasing. Eating Behaviors. 2001;2(3):215–236. doi: 10.1016/s1471-0153(01)00030-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynagh M, Cliff K, Morgan PJ. Attitudes and beliefs of nonspecialist and specialist trainee health and physical education teachers towards obese children: Evidence for "anti-fat" bias. Journal of School Health. 2015;85(9):595–603. doi: 10.1111/josh.12287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall WA, Tanner JM. Variations in pattern of pubertal changes in girls. Archives of Disease in Children. 1969;44(235):291–303. doi: 10.1136/adc.44.235.291. Retrieved from http://adc.bmj.com/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall WA, Tanner JM. Variations in the pattern of pubertal changes in boys. Archives of Disease in Children. 1970;45(239):13–23. doi: 10.1136/adc.45.239.13. Retrieved from http://adc.bmj.com/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe MP, Ricciardelli LA. A prospective study of pressures from parents, peers, and the media on extreme weight change behaviors among adolescent boys and girls. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2005;43(5):653–668. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumark-Sztainer D, Falkner N, Story M, Perry C, Hannan PJ, Mulert S. Weight-teasing among adolescents: correlates with weight status and disordered eating behaviors. International Journal of Obesity. 2002;26(1):123–131. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801853. doi:10.1038=sj=ijo=0801853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Lawman HG, et al. TRends in obesity prevalence among children and adolescents in the united states, 1988–1994 through 2013–2014. JAMA. 2016;315(21):2292–2299. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.6361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papp I, Urban R, Czegledi E, Babusa B, Tury F. Testing the Tripartite Influence Model of body image and eating disturbance among Hungarian adolescents. Body Image. 2013;10(2):232–242. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2012.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phares V, Steinberg AR, Thompson JK. Gender differences in peer and parental influences: Body image disturbance, self-worth, and psychological functioning in preadolescent children. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2004;33(5):421–429. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects of multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40(3):879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Przybylowicz KE, Jesiolowska D, Obara-Golebiowska M, Anotniak L. A subjective dissatisfaction with body weight in young women: Do eating behaviours play a role? Roczniki Państwowego Zakładu Higieny. 2014;65(3):243–249. Retrieved from http://www.pzh.gov.pl/en/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puhl RM, Heuer CM. The stigma of obesity: A review and update. Obesity. 2009;17(5):941–964. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers RF, Ganchou C, Franko DL, Chabrol H. Drive for muscularity and disordered eating among French adolescent boys: a sociocultural model. Body Image. 2012;9(3):318–323. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scalici F, Schulz PJ. Influence of perceived parent and peer endorsement on adolescent smoking intentions: Parents have more say, but their influence wanes as kids get older. PLOS One. 2012;9(7):1–7. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101275. doi:0.1371/journal.pone.0101275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer LM, Burke NL, Thompson JK, Dedrick RF, Heinberg LJ, Calogero RM, Swami V. Development and validation of the Sociocultural Attitudes Towards Appearance Questionnaire-4 (SATAQ-4) Psychol Assess. 2015;27(1):54–67. doi: 10.1037/a0037917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shomaker LB, Furman W. Interpersonal influences on late adolescent girls' and boys' disordered eating. Eating Behaviors. 2009;10(2):97–106. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shomaker LB, Furman W. A prospective investigation of interpersonal influences on the pursuit of muscularity in late adolescent boys and girls. J Health Psychol. 2010;15(3):391–404. doi: 10.1177/1359105309350514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shomaker LB, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Yanovski JA. Disinhibited eating and body weight in youth. In: Preedy VR, Watson RR, Martin CR, editors. International Handbook of Behavior, Diet, and Nutrition. 1. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Slater A, Tiggemann M. Gender differences in adolescent sport participation, teasing, self-objectification and body image concerns. J Adolesc. 2011;34(3):455–463. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smolak L, Murnen SK. Drive for leanness: Assessment and relationship to gender, gender role and objectification. Body Image. 2008;5(3):251–260. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2008.03.004. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanford JN, McCabe MP. Body Image Ideal among Males and Females: Sociocultural Influences and Focus on Different Body Parts. J Health Psychol. 2002;7(6):675–684. doi: 10.1177/1359105302007006871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E. A prospective test of the dual-pathway model of bulimic pathology: Mediating effects of dieting and negative affect. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110(1):124–135. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.1.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Nemeroff C, Shaw H. Test of the Dual Pathway model of bulimia nervosa: Evidence for dietary restraint and affect regulation mechanisms. Journal of Social and Clinical Pyschology. 1996;15(3):340–363. [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Schupak-Neuberg E, Shaw H, Stein RI. Relation of media exposure to eating disorder symptomatology: An examination of mediating mechanisms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1994;103(4):836–840. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.103.4.836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Trost A, Chase A. Healthy weight control and dissonance-based eating disorder prevention programs: Results from a controlled trial. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2002;33(1):10–21. doi: 10.1002/eat.10109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson SA, Crow SJ, Le Grange D, Swendsen J, Merikangas KR. Prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in adolescents. Results from the national comorbidity survey replication adolescent supplement. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(7):714–723. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanofsky-Kraff M, Theim KR, Yanovski SZ, Bassett AM, Burns NP, Ranzenhofer LM, Yanovski JA. Validation of the emotional eating scale adapted for use in children and adolescents (EES-C) International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2007;40(3):232–240. doi: 10.1002/eat.20362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JK, Heinberg LJ, Altabe M, Tantleff-Dunn D. Exacting beauty: Theory, assessment, and treatment of body image disturbance. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JK, van den Berg P, Roehrig M, Guarda AS, Heinberg LJ. The sociocultural attitudes towards appearance scale (SATAQ-3): Development and validation. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2004;35(3):293–304. doi: 10.1002/eat.10257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiggemann M, Martins Y, Churchett L. Beyond muscles: Unexplored parts of men's body image. Journal of Health Psychology. 2008;13(8):1163–1172. doi: 10.1177/1359105308095971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vannucci A, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Corsby RD, Ranzenhofer LM, Shomaker LB, Field SE, Yanovski JA. Latent profile analysis to determine the typology of disinhibited eating behaviors in children and adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2013;81(3):494–507. doi: 10.1037/a0031209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamiya Y, Shroff H, Thompson JK. The Tripartite Influence Model of body image and eating disturbance: A replication with a Japanese sample. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2008;41(1):88–91. doi: 10.1002/eat.20444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young EA, Clopton JR, Bleckley MK. Perfectionism, low self-esteem, and family factor as predictors of bulimic behavior. Eating Behaviors. 2004;5(4):273–283. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeeck A, Stelzer N, Woolfgang Linster H, Joos A, Hartmann A. Emotion and eating in binge eating disorder and obesity. European Eating Disorder Review. 2010;19(5):426–437. doi: 10.1002/erv.1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]