Abstract

Planktothrix is a dominant cyanobacterial genus forming toxic blooms in temperate freshwater ecosystems. We sequenced the genome of planktic and non planktic Planktothrix strains to better represent this genus diversity and life style at the genomic level. Benthic and biphasic strains are rooting the Planktothrix phylogenetic tree and widely expand the pangenome of this genus. We further investigated in silico the genetic potential dedicated to gas vesicles production, nitrogen fixation as well as natural product synthesis and conducted complementary experimental tests by cell culture, microscopy and mass spectrometry. Significant differences for the investigated features could be evidenced between strains of different life styles. The benthic Planktothrix strains showed unexpected characteristics such as buoyancy, nitrogen fixation capacity and unique natural product features. In comparison with Microcystis, another dominant toxic bloom-forming genus in freshwater ecosystem, different evolutionary strategies were highlighted notably as Planktothrix exhibits an overall greater genetic diversity but a smaller genomic plasticity than Microcystis. Our results are shedding light on Planktothrix evolution, phylogeny and physiology in the frame of their diverse life styles.

Cyanobacteria is a fascinating phylum considering the large diversity of morphological, physiological, ecological, toxicological and genetic characteristics of these microorganisms (e.g. Bothe et al.1, Calteau et al.2, Careya et al.3). This diversity has motivated a huge number of publications in the last decades but many questions of great interest concerning for example the development of multicellularity4 or the diversification of life styles into this phylum5 are still far from being resolved. Similarly, the taxonomy of Cyanobacteria remains uncertain for many groups.

In recent years, numerous genomes from diverse cyanobacterial genera permitted to enlarge our vision on the genomic diversity of cyanobacteria6. This concerned in particular filamentous cyanobacteria, which were poorly investigated until now. Classified in the order Oscillatoriales7, the filamentous cyanobacteria are indeed widely dispersed in the radiation of the cyanobacterial phylum6, and they display various physiological capacities (for example, diazotrophy, motility and salt tolerance) and ecological strategies for niche adaptation.

Within Oscillatoriales, the genus Planktothrix was formed to contain free-floating solitary trichomes distinguished in nine planktic species8. However, a benthic strain was recently isolated in a freshwater biofilm in New Zealand9, further completed by a larger set of benthic Planktothrix strains closely related to the planktic forms of Planktothrix10. As observed for the heterocystous genus Nodularia11, the coexistence of planktic and benthic species in the genus Planktothrix makes it a good candidate for studying genome adaptation linked to these two ways of life.

The genus Planktothrix is also well investigated because it blooms frequently in freshwater ecosystems of temperate areas. This motivated a lot of works on the buoyant capabilities12,13,14,15 of the planktic isolates considering their vertical migration in the water column. One of the recently described benthic species was named with respect to its gas vesicle characteristics (Planktothrix paucivesiculata PCC 9631)10, raising questions on the relevance of gas vesicles in a benthic way of life. To date, no information is available on the genetic basis of buoyancy through the whole genus including the biphasic and benthic strains.

The recurrent toxicity of Planktothrix blooms drove most of the works to be performed on their natural products potential, in particular on the biosynthesis of various microcystin variants (e.g. Briand et al.16, Kurmayer & Gumpenberger17). Beyond microcystins, Planktothrix is also able to produce others natural products through versatile non-ribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS) and polyketide synthase (PKS) biosynthetic pathways or as ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptides (RiPPs)18,19,20,21. Notably, a compound previously unrelated to this genus has been recently found in Planktothrix paucivesiculata PCC 963121 leading us to expect more unusual Planktothrix compounds in their various life styles.

This study aims (i) at better representing the Planktothrix genus diversity and life style at the genomic level and (ii) at investigating the genetic basis behind few common and divergent metabolic features between benthic and planktic strains. In this frame and in complement to the recent genomic data obtained for nine closely related planktic Planktothrix forming blooms in Nordic lakes22,23, we sequenced the genomes of six strains from the Pasteur Culture Collection of Cyanobacteria (PCC) including four biphasic/benthic strains. We investigated the capability of these strains to produce aerotopes and their capacity to fix nitrogen. We also examined their genetic potential for natural products to find the diverse pathways present in this oscillatorialean genus.

Results

General features of the six Planktothrix genomes studied

The general features of the six Planktothrix strains, their appearances in cultures and their genomes sequenced in this study are presented in Table 1, Fig. S1 and Table 2. The complete P. agardhii PCC 7805 genome contains one chromosome (4.7 Mb), one megaplasmid (151 kb) and one cryptic plasmid (4.5 kb). The simultaneous presence of a resolvase gene (rsvA; PLAM_mp0003) and a homolog to tnpA transposase (PLAM_mp0004) associated to a fold-coverage comparable to that of the chromosome, suggested that the megaplasmid could be integrative. Using PCC 7805 genome as reference, we identified the scaffolds belonging to the chromosome, the megaplasmid and the plasmid in P. rubescens PCC 7821 (Table 2). However, the resolvase and tnpA-like genes were not found into PCC 7821 megaplasmid, although fold-coverage was the same than that of the chromosome. The genome size of the benthic/biphasic life style strains, between 5.9 Mb (Planktothrix sp. PCC 11201) and 6.7 Mb (P. tepida PCC 9214), was larger than the average genome size of planktic strains (Table 2).

Table 1. Description of the six Planktothrix strains studied.

| Strains | Geographical origin and date of isolation | Life style* |

|---|---|---|

| P. agardhii PCC 7805 | Veluwemeer, The Netherland, 1972 | Planktic |

| P. rubescens PCC 7821 | Gjersjøen lake, Norway, 1971 | Planktic |

| P. serta PCC 8927 | Berre pond, France, 1988 | Benthic |

| P. tepida PCC 9214 | Gut of Culex decens, Central African Republic, 1989 | Biphasic |

| P. paucivesiculata PCC 9631 | Marne river, France, 1996 | Benthic |

| Planktothrix sp. PCC 11201 | Waitaki river, New Zealand, 2012 | Benthic |

*See Fig. S1.

Table 2. General features and accession numbers of the six Planktothrix genomes.

| Strains | Statut* | Contigs AC | Genome size (bp) | GC% | No of scaffolds | No of contigs | CDS | Average CDS length (bp) | misc_RNA | rRNA | tRNA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. agardhii PCC 7805 | Complete | Chr. | LO018304 | 4,700,732 | 39.62 | 1 | 1 | 4,296 | 937 | 14 | 3 | 40 |

| MP | LO018305 | 151,88 | 39.87 | 1 | 1 | 150 | 902 | / | / | / | ||

| P | LO018306 | 4,522 | 38.35 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 522 | / | / | / | ||

| P. rubescens PCC 7821 | Chr. | CZCZ01000001-08 | 5,391,870 | 39.47 | 5 | 8 | 4,884 | 951 | 18 | 1 | 40 | |

| WGS | MP | CZCZ01000009-12 | 196,481 | 39.01 | 4 | 4 | 178 | 941 | / | / | / | |

| P | CZCZ01000013 | 12,935 | 41.04 | 1 | 1 | 18 | 511 | / | / | / | ||

| P. serta PCC 8927 | WGS | / | CZCU01000001-178 | 6,250,174 | 39.58 | 157 | 178 | 5,729 | 940 | 12 | 3 | 42 |

| Planktothrix sp. PCC 11201 | WGS | / | CZCT01000001-151 | 5,964,975 | 40.14 | 103 | 151 | 5,202 | 1,002 | 17 | 6 | 48 |

| P. tepida PCC 9214 | WGS | / | CZDF01000001-209 | 6,725,787 | 39.47 | 191 | 209 | 6,043 | 957 | 33 | 3 | 48 |

| P. paucivesiculata PCC 9631 | WGS | / | CZCS01000001-244 | 6,072,585 | 40.10 | 184 | 244 | 5,365 | 994 | 18 | 6 | 48 |

Our Planktothrix genomes were compared to the nine Planktothrix genomes from Nordic lakes already available. Using the genome of PCC 7805 as reference, the genomes of the planktic strains showed synteny values above 80%, whereas the ones of the four Planktothrix with another life style were slightly lower (Fig. S2). A non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) analysis on the clusters of orthologous groups (COG) further revealed that most of the Nordic Planktothrix grouped together whereas two planktic Planktothrix PCC 7805 and NIVA CYA 126/8, two Planktothrix PCC 9214 and PCC 8927 and the two Planktothrix PCC 11201 and PCC 9631 formed three distinguished groups apart (Fig. S3). The overall comparison of the COG showed an enrichment of the benthic and biphasic strains in genes related to signal transduction mechanisms (Table S1). In addition, 38 to 48 tRNAs were found in the Planktothrix genomes, the benthic and biphasic strains having more tRNA than the planktic ones (Table S2).

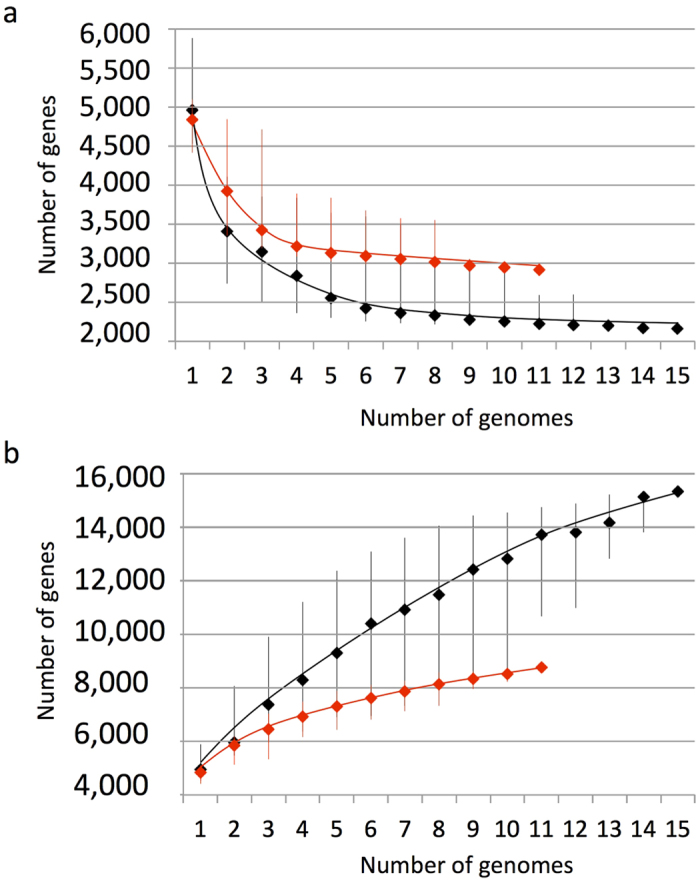

The core and pan genome analysis of all Planktothrix genomes revealed about 2,200 genes for the core, and about 3,000 genes when considering only the planktic ones (Fig. 1a). With regard to the pangenome, the gene accumulation curve did not reach a plateau when considering all genomes, while the almost asymptotic curve obtained with genomes from planktic strains suggested between 8,000 and 9,000 genes in their pangenome (Fig. 1b).

Figure 1.

Sizes estimation of the core genome in number of conserved genes (a) and pangenome in number of specific genes (b) of all Planktothrix (in black) and the planktic strains only (in red).

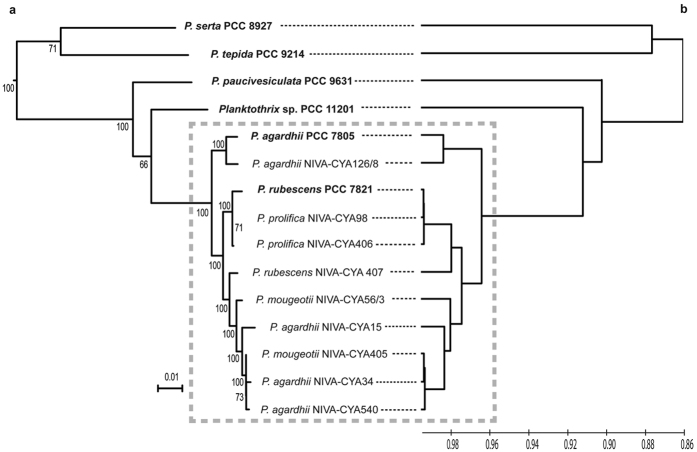

Finally, the genetic relationship between our six strains and the nine available planktic Planktothrix was studied by a Maximum-Likelihood phylogenetic approach performed on 586 concatenated proteins from the core genomes and by a phenetic approach (UPGMA) performed on the average nucleotide identity values. A good overall congruence between the trees was observed with a well-defined cluster containing all the planktic strains rooted by the four non planktic strains at the basis of the tree (Fig. 2). An extended phylogeny on 29 genes with the closest cyanobacterial relatives indicated the same topology further rooted by a cluster with three Arthrospira and the marine Lyngbya sp. CCY 9616 (Fig. S4). The same tree topology was obtained using the 16 S rRNA gene sequences (data not shown). From these findings, it appeared that the eleven planktic strains (nine previously sequenced and two new ones) belong to the same species while the four benthic or biphasic strains at the tip of longer branches are more heterogeneous and belong to different species.

Figure 2. Genetic relationships between the fifteen available Planktothrix genomes.

(a) Phylogenetic tree obtained using a Maximum Likelihood method on 586 concatenated proteins.(b) Phenetic tree (UPGMA) obtained from the ANIm values between all genomes. Grey rectangle contains all the planktic strains.

Gas vesicles in planktic and benthic forms of Planktothrix

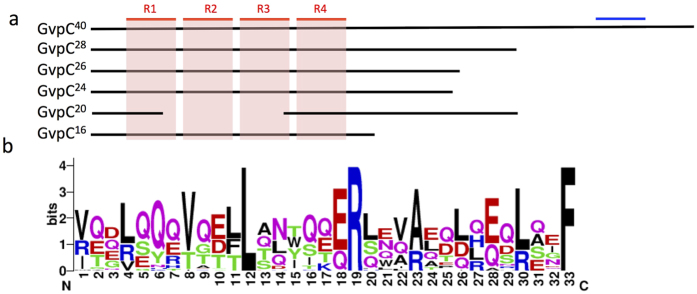

The gas vesicles are essential for the floatability of planktic Planktothrix, but whether they are needed in the life style of the benthic Planktothrix remained to be investigated. The gvp gene clusters were present in all Planktothrix genomes whether the strains had a planktic, benthic or biphasic life style. The quality of the genome assemblies and the different sequencing techniques did not allow analyzing the organization of the gvp gene clusters. However, the genes gvpA, gvpC, gvpN, gvpJ, gvpK, gvpF/L, gvpG and gvpV were found in all Planktothrix genomes, while the gene gvpW was absent only from the genome of benthic strain PCC 11201. The GvpC protein being a structurant element of the size of the gas vesicles, we examined the diversity of the gvpC gene of our Planktothrix dataset. Indeed, the gvpC gene appeared to code more GvpC protein variants than expected. The three commonly described length variants of 16 kDa GvpC in P. prolifica NIVA CYA 540, 20.1 kDa GvpC in P. rubescens PCC 7821 and 28.6 kDa GvpC in P. mougeotii NIVA CYA 56-3 and P. agardhii PCC 7805 were completed with a 24.3 kDa GvpC in P. agardhii NIVA CYA 15, a 26.3 kDa GvpC in P. mougeotii NIVA CYA 405 and in P. agardhii NIVA CYA 34, and a larger GvpC variant of about 40 kDa in all non planktic strains (39.8 kDa GvpC in Planktothrix sp. PCC 11201 and 39.5 kDa GvpC in P. serta PCC 8927, P. tepida PCC 9214 and P. paucivesiculata PCC 9631). The phylogeny of the GvpC protein sequences of Planktothrix (Fig. S5) is congruent with the one obtained for the taxonomic markers, indicating that GvpC is likely vertically inherited. Aware of the GvpC size discrepancy between planktic and non planktic Planktothrix, we investigated the gas vesicles of the benthic Planktothrix sp. PCC 11201 and the planktic P. agardhii PCC 7805, which did not shown any difference in abundance and size of their aerotopes (Fig. S6). Interestingly, the alignment of GvpC40 with the smallest GvpC proteins revealed 33 amino acid long degenerated motifs repeated (Fig. 3a). These GvpC motifs present in four repeats in GvpC16,24,26,28,40 contained invariant amino acids at positions 12, 19 and 33 similar to the ones described for the repeated motifs of Anabaena and Calothrix GvpC (Fig. 3b). The motif was also present in the N-terminal part of truncated GvpC20 of PCC 7821, but it would not have been found without comparison with the other Planktothrix GvpC variants. In addition, the C-terminal GvpC40 was similar at 78% to a 60 amino acid long sequence of the C-terminal GvpC of 40.5 kDa in Geitlerinema sp. PCC 7407 (WP_015171019.1) and, a 28 amino acid stretch in the C-terminal GvpC40 shared 64% sequence identity with the protein GvpN of Planktothrix (Fig. 3a).

Figure 3. Scheme of the structure of GvpC proteins of Planktothrix.

(a) Alignment of GvpC protein variants of Planktothrix sp. with GvpC40 from PCC 11201, PCC 8927, PCC 9214 and PCC 9631, GvpC28 from P. agardhii PCC 7805 and P. mougeotti NIVA CYA 56-3, GvpC26 from NIVA CYA 34 and NIVA CYA 405, GvpC24 from NIVA CYA 15, GvpC20 from PCC 7821 and GvpC16 from NIVA CYA 540. The red lines indicate the localisation of the four degenerated repeats R1, R2, R3, and R4. The blue line indicate the N terminal domain presenting homology with GvpN; (b) Consensus sequence found between the R1, R2, R3, and R4 repeats. LRF residues are conserved in Anabaena and Calothrix repeats as well49.

Nitrogen fixation in Planktothrix strains

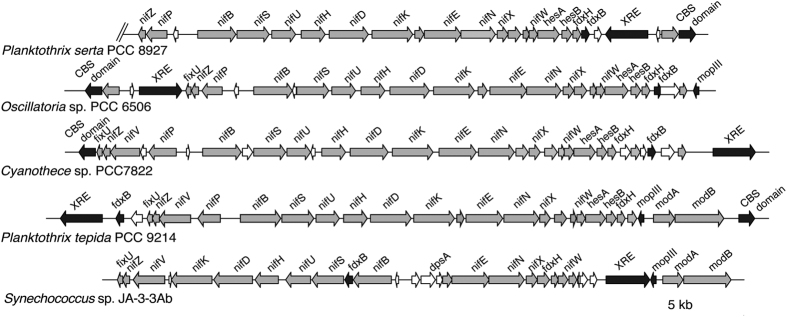

Among all the Planktothrix genomes studied, P. tepida PCC 9214 and P. serta PCC 8927 harboured the entire nif gene cluster (Fig. 4). These clusters contained the nitrogenase structural genes nifH, nifD, and nifK flanked on the left by the nifU, nifS, nifB, nifP and nifZ genes and on the right by nifE, nifN, nifX, nifW, hesA, hesB, and fdxH genes. This general organization of the nif gene cluster was identical in Cyanothece sp. PCC 7822 and Oscillatoria sp. PCC 6506, but differed from the one of Synechococcus sp. JA-3-3Ab. The genes nifV and fixU were not included in the nif cluster of P. serta PCC 8927 but found elsewhere in the genome. Interestingly, both P. serta PCC 8927 and P. tepida PCC 9214 nif clusters were flanked by the fdxB gene and a gene encoding a XRE (Xenobiotique response element) family transcriptional regulator. This regulator, named PatB in heterocystous cyanobacteria and CnfR in other diazotrophic cyanobacteria, was identified as the master regulator for the nif genes24. Moreover, three molybdenum transporter genes (modIII, modA, and modB) also flanked the nif gene cluster of P. tepida PCC 9214, as the one of Synechococcus sp. JA-3-3Ab.

Figure 4. Organization of the Nif gene clusters in two benthic Planktothrix strains PCC 8927 and PCC 9214 compared to the ones in other non-heterocystous cyanobacteria.

The conserved genes of the nif cluster locus are indicated in grey, the genes indicated in black are present and rearranged between the clusters, the genes indicated in white are not conserved.

A phylogenetic analysis performed on the concatenated sequences of nifBDHSU genes of diverse diazotrophic cyanobacteria revealed that the nif cluster of PCC 8927 is not closely related to the one of PCC 9214 (Fig. S7). The nifBDHSU of P. serta PCC 8927 is located in a clade containing the benthic filamentous Oscillatoria spp. PCC 6506 and PCC 6407, Leptolyngbya boryana PCC 6306, the unicellular Cyanothece sp. PCC 7425 and diverse heterocystous strains such as Anabeana variabilis ATCC 29413, Fischerella spp. PCC 9605 and JSC-11, and Nodularia spumigena CCY 9414. On the other hand, the nifBDHSU of P. tepida PCC 9214 is placed between the clade of the Synechococcus from Yellowstone and the clade containing P. serta PCC 8927 and other cyanobacterial diazotrophs, and the nodes connecting this strain with these two clades are not supported by bootstrap values. Furthermore, single nif gene phylogenies (data not shown) were incongruent with the location PCC 9214 in the nifBDHSU tree, while the locus containing nifBDHSU genes is conserved in the 26 nif gene clusters examined (Fig. S7). This indicated that PCC 9214 hold a mosaic cyanobacterial nif cluster. To assess if the nif gene clusters were functional in both strains (PCC 9214 and PCC 8927), growth tests were performed under different nitrogen concentrations, with the other Planktothrix strains as negative controls and the nitrogen fixer Cyanothece sp. PCC 7822 as positive control. All the strains cultivated under continuous light died under nitrogen starvation conditions. When a day/night rhythm was applied, P. serta PCC 8927 was able to grow and develop a thick biofilm under nitrogen starvation conditions, but not P. tepida PCC 9214 (Fig. S8). This suggested that in our culture conditions, only P. serta PCC 8927 was able to fix N2.

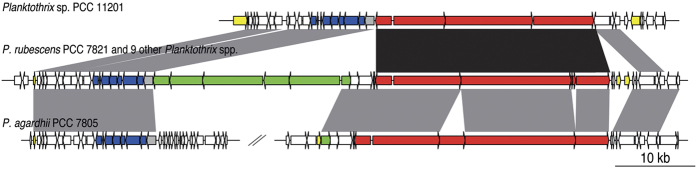

Genetic potential dedicated to natural products in the toxic Planktothrix

Twenty biosynthetic gene clusters dedicated to natural products (BGCs) were identified in Planktothrix genomes (Table 3). The BGCs of 3.4 to 92.8 kb-long belong to RiPPs, NRPS, PKS and hybrids of the two last categories. The strains contained two to nine BGCs accounting for 0.9 to 3.7% of the total genome size. When looking at the distribution of all these BGCs among all the available Planktothrix genomes, it appeared that the planktic strains and the benthic strain PCC 11201 grouped together, while the three other benthic strains were much more dispersed revealing drastic differences in their BGC content (Fig. S9). More in details, ten BGCs previously described in Planktothrix encoding the biosynthesis of aeruginosin (aer), cyanobactin (pat), cyanopeptolin (oci), luminaolide B (lum), microcystin (mcy), microviridin (mdn), microginin (mic), anabaenopeptin (apt) oscillatorin (osc) and prenylagaramide (pag), are conserved with a high amino acid identity (AAI) in this clade (Table 3). The BGCs apt, mic, and oci appeared localised in a ~66 kb genomic island for several Planktothrix strains as they were previously showed co-localised in Planktothrix rubescens NIVA CYA 9819 (Fig. 5). This genomic island was found in nine other planktic strains (PCC 7821, NIVA-CYA 15, NIVA-CYA 34, NIVA-CYA 56/3, NIVA-CYA 405, NIVA-CYA 406, NIVA-CYA 407, NIVA-CYA 540 and NIVA-CYA 126/8), and more strikingly in the genome of the benthic Planktothrix strain PCC 11201. This locus presented the features of a genomic island such as a size >20 kb, the presence of mobile elements (insertion sequence and transposases at their extremities) and a compositional bias (2 mer to 8 mer compositional bias of distribution, codon usage bias, and for PCC 11201 an additional GC percentage deviation (−1 Standard Deviation)). In addition, this genomic island region was split in two regions in P. agardhii PCC 7805 with the deletion of most apt genes compared to the ten other planktic Planktothrix. However, the remaining apt gene and the flanking regions witness a previous occurrence of such co-localised organization in the genome of PCC 7805.

Table 3. Distribution and diversity of the gene clusters involved in the biosynthesis of natural products of the studied Planktothrix.

| RiPPs |

NRPS |

NRPS/PKS hybrid |

PKS |

|||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mdn | pat-like | osc | pag | RiPP1 | aer | apt | oci | PNL2 | PNL3 | mcy | mic | has-like | PNL1 | PHL1 | lum | tto | PPL1 | PPL2 | PPL3 | |

| Size (kb) | 7,1–7,3 | 11,1 | 8,2–11,8 | 9,3–11,4 | 3,4 | 22,8–25,7 | 23,7 | 27,5–32,3 | 11 | 11,3 | 49,3–51,1 | 34,5 | 43,2 | 25,1 | 28 | 89,5 | 92,8 | 11,7 | 8 | 6,2 |

| PCC 7821 | Ref. | — | Ref. | Ref. | — | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | 100£ | — | Ref. | 100£ | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| PCC 7805 | 93 | — | 97 | 96 | — | 82 | partE | 91 | — | — | — | — | — | 96£ | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| PCC 11201 | 92 | — | 83 | 92 + partABC | — | 54 | — | 55 | — | — | 73 | — | — | — | — | — | 76§ | — | — | — |

| PCC 9214 | — | — | — | — | — | — | partBCD | — | — | Ref. | — | — | — | — | Ref. | — | — | — | Ref. | Ref. |

| PCC 8927 | — | — | — | — | Ref. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 66$ | — | — | — | — | Ref. | — | — |

| PCC 9631 | — | 91* | — | partGEF | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | Ref. | — | — | — | — |

Ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptides (RiPPs), non-ribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS), polyketide synthase (PKS) and NRPS/PKS hybrids were compared by amino acid identity (% AAI) of NRPS/PKS/cyanobactin protease to a reference Planktothrix strain (Ref.), Microcystis sp. PCC 9432 (*), Anabaena sp. SYKE748A ($), Planktothrix prolifica NIVA-CYA 98 (£) and Scytonema sp. PCC 10023 (§). Incomplete gene clusters are indicated with the conserved genes (part). The biosynthetic gene clusters of aeruginosin (aer), anabaenopeptin (apt), cyanopeptolin (oci), luminaolide (lum), microcyclamide (mca), microcystin (mcy), microginin (mic), microviridin (mdn), oscillatorin (osc), prenylagaramide (pag), tolytoxin (tto) were detected as well as one like hassallidin (has-like), and another one like cyanobactin (pat-like), and other Planktothrix gene clusters not corresponding to know molecules named Planktothrix NRPS-like (PNL), Planktothrix PKS-like (PPL) and Planktothrix hybrid-like (PHL).

Figure 5. Genomic island dedicated to natural products in Planktothrix.

Similar genomic islands containing biosynthetic gene clusters of apt (green), oci (red) and mdn (blue) were found in P. sp. PCC 11201, P. rubescens PCC 7821 identical to the one found in nine planktonic Planktothrix spp. (NIVA-CYA 15, NIVA-CYA 34, NIVA-CYA 56/3, NIVA-CYA 98, NIVA-CYA 126/8, NIVA-CYA 405, NIVA-CYA 406, NIVA-CYA 407 and NIVA-CYA 540) and in P. agardhii PCC 7805. In the latter, the genomic island is not evidenced by the current assembly of the contigs, but one remaining gene of apt and the flanking regions witness a previous occurrence of the same genomic island organization. Clusters with conserved sequence and domain organization are connected in grey and in black when reorganized. The genetic island in addition of apt, oci and mdn gene clusters contained other genes putatively involved in these pathways (in grey), flanking genes (in white) and genes of mobility such as insertion sequences and transposases (in yellow).

Among the other BGCs, two trans-AT PKS gene clusters were found in the genomes of PCC 9631 and PCC 11201. The trans-AT PKS gene cluster of PCC 9631 encode the biosynthetic pathway for luminaolide B, while the one of PCC 11201 exhibited a homology of 76% to the tolytoxin gene cluster (tto) described for Scytonema sp. PCC 1002321. We confirmed the production of tolytoxin in PCC 11201 by HPLC, MS, and NMR (Fig. S10). In addition, a has-like gene cluster was found in Planktothrix serta PCC 8927 with four NRPS genes similar at 66% to the hassallidin gene cluster found in Anabaena sp. SYKE748A25. However, the characterisation of the other ORFs of this has-like gene cluster and the eventual natural product synthesis will need further study.

The other gene clusters displayed variability in their size, gene composition and organization, and precursors (Table 3). Genome mining allowed the comparison of BGCs pat and mic to homologous clusters in other genomes. The cyanobactin BGC (pat-like) of PCC 9631 was similar at 91% to aeruginosamide gene cluster of Microcystis sp. PCC 9432, and its structure organisation recalled the ones of microcyclamide cluster of Microcystis sp. PCC 7806 and aesturamide cluster of Lyngbya sp. CCY 961626,27. The structure of these BGCs and comparison of their precursor peptides suggested the production by PCC 9631 of a cyclic cyanobactin with two prenylations (Fig. S11). Similarly, the mic BGC on the megaplasmid of PCC 7821 was identical to one encoding microginin in Planktothrix prolifica NIVA-CYA 98 and 73% similar to one in Microcystis aeruginosa PCC 943219,28. The mic cluster synteny comparison indicated four additional ORFs coding for a CAL domain, a peptidyl carrier protein domain, an O-methyltransferase that might be involved in the synthesis of the microginin (Fig. S12).

The remaining gene clusters were not linked to known natural products. Two orphans PNL1 and PNL2 were previously described in the Planktothrix NIVA CYA 9819. PNL1 located on the megaplasmid of PCC 7805 shared 96% AAI with P. prolifica NIVA-CYA 98 and 66% AAI with Spirulina major PCC 6313. Finally, the bacteriocin-like gene cluster RiPP1 was similar to a gene cluster in Oscillatoria sp. PCC 10802 (84%). The gene clusters PNL3, PHL1, PPL1, PPL2 and PPL3 had no significant similarity in databases.

Discussion

Our comparative genomic approach on benthic and planktic Planktothrix strains has permitted to clarify the phylogenetic relationships between all these strains. Their ANI values were supporting their placement into the same genus taxa as recently proposed by Gaget et al.10 by using 16S rRNA and MLST on few other stable genetic markers. Interestingly, this genus appear to be close to Arthrospira genus and in a lesser extent to some oscillatorian strains, which contain benthic and planktic species. Inside the Plantothrix genus, both ANI values and pan genome data suggest that the 15 planktic strains including green and red ecotypes, belong to a single species, whereas the four benthic and biphasic strains are split into four different species at the root the planktic clade. The diversity observed among the benthic Planktothrix recall the one reported for Nodularia11. These findings are interesting to consider in regard to the data recently obtained showing that the appearance of benthic cyanobacteria precludes the emergency of planktic ones in marine ecosystems5. As for marine cyanobacteria, benthic life style might precede planktic life style in freshwater ecosystems, at least for this taxonomical group.

In the Planktothrix genome comparison, we paid a special attention to genetic differences between benthic and planktic strains. The genes involved in the biosynthesis of gas vesicles that confer buoyancy to the cells displayed significant variations inside the Planktothrix genus. Indeed, all benthic Planktothrix shared a GvpC40 protein containing four degenerated repeat sequences while planktic strain GvpC were smaller and more diverse in size (from GvpC16 to GvpC28). The shorter GvpC proteins of the planktic strains kept trace of the four repeats identified in the benthic strains. These variations are interesting in regard to the life style of the strains. As previously shown for planktic strains12,29, variations in gvpC genes seem to be directly associated to the differentiation of various gas vesicle phenotypes, and consequently, to their adaptation to various environmental conditions. In the benthic strains, the presence of gas vesicles could be useful for the propagation of their filaments or to the detachment of mature biofilms from their support.

Complete nif gene clusters were found in two benthic Planktothrix strains, but only one exhibited nitrogen fixation capacity in our conditions. The nitrogen fixation is active in several unicellular, filamentous and most of heterocystous cyanobacteria providing advantages over concurrent species, in oligotrophic environments or with the increase of atmospheric CO230. Nitrogen fixation was mostly studied in Trichodesmium and Cyanothece proliferating in nitrogen-depleted ocean, and in Anabaena for characterizing the cellular differentiation dedicated to this process30,31,32. However, this capacity was also reported in benthic cyanobacteria of the genus Hydrocoleum33. In our experimental conditions, only Planktothrix serta PCC 8927 was able to fix N2 as shown by its ability to grow in a medium depeleted in nitrogen. The other strain containing the complete nif gene cluster, Planktothrix tepida PCC 9214, was unable to grow in this medium, and may need as several filamentous non heterocystous strains belonging to the genera Phormidium, Pseudanabaena and Oscillatoria, micro-oxic or anoxic conditions to fix N234. As the other non planktic Planktothrix studied did not fix nitrogen, this capacity seems not linked to their life style, even if it is known that benthic microorganisms are mostly found in oligotrophic water containing low nitrogen concentrations. As the Planktothrix clade is engulfed into a larger oscillatorian clade comprising several diazotrophic cyanobacteria (Fig. S4), the evolutionary origin of the nif in Planktothrix seems coherent with the vertical inheritance of diazotrophy in most of cyanobacteria, with repeated loss in non nitrogen-fixers35, and nif gene cluster rearrangements such as in PCC 9214.

Concerning the potential for the production of natural products, significant differences were found between the benthic and planktic strains. Interestingly, the benthic strain PCC 11201, which is phylogenetically more closely related to the planktic strains, shared numerous BGCs with them while the three other non planktic strains displayed more difference in their potential to produce secondary metabolites. In particular, PCC 11201 contains a large portion of the genomic island comprising anabeanopeptin, cyanopeptolin and microviridin that is also present in most of the genomes of the free-living Planktothrix. This co-localization was previously reported in the genome of Planktothrix NIVA CYA 9819, whereas genomic islands in cyanobacteria were previously associated to the transfer of light harvesting phycobilisome rod complexes or to glycosyltransferases and transport proteins36,37. Such a large genomic island dedicated to two NRPS and one RiPP in Planktothrix was not reported previously in the cyanobacterial BGCs studied at phylum-wide level2. However, other BGC arrangements on genomic islands were described in other bacteria27,38. Whether the co-localization is linked to the co-regulation of these BGCs remains to be investigated. Several other BGCs encoded for yet unknown natural products, while several Planktothrix compounds are not related to any genetic data. Indeed, the comparisons of unknown BGCs lead to those from highly unrelated organisms such as myxobacteria from soil and Entotheonella-symbiont of marin sponges21. We uncovered in Planktothrix sp. PCC 11201 the polyketide tolytoxin, typically found otherwise in heterocystous cyanobacteria such as Tolypothrix and Scytonema. Similarly, a close congener of luminaolide B recently described from Planktothrix paucivesiculata PCC 9631 was previously reported from a marine coral-consortium21. Both tolytoxin and luminaolide B are produced through related trans-AT PKSs21, an enzyme family that seems to occur more often in the cyanobacterial phylum than previously anticipated. Genome mining of BGCs in the diversity of the Planktothrix revealed a wider potential in the benthic and biphasic life styles that the one seen so far from closely related planktic Planktothrix.

Finally, it is also interesting to compare the main characteristics of the planktic Planktothrix genomes with those of Microcystis, another major toxic bloom-forming cyanobacteria in freshwater ecosystems. On one hand, Microcystis genomes are characterized by a very high genomic plasticity featured by the high number of repeated and insertion sequences, and strickingly low synteny value between 12 closely related strains28. It was previously hypothesized that Microcystis genomic plasticity allowed these species to occupy a wide range of environments28. On the other hand, the 11 planktic Planktothrix genomes investigated in this study revealed higher synteny values and smaller pan genome. Knowing that planktic Planktothrix blooms mainly occur in temperate and cold areas when Microcystis blooms are found in all latitudes, these genomic differences might be associated for Planktothrix to a smaller ability to develop in various environmental conditions. Interestingly, our genomic data confirm that red and green Planktothrix strains belong to the same species and consequently that they can be considered as ecotypes occupying different ecological niches, the red strains being able to bloom in deep and cold lakes when green strains mostly bloom in temperate shallow lakes22. The differentiation of ecotypes occupying separate niches has been described in marine picocyanobacteria belonging to the Prochlorococcus genus, but the Prochlorococcus genomes are characterized by a reduced size while there is no genome size reduction in Planktothrix. As proposed by Humbert et al.28 the larger variability in environmental conditions of freshwater ecosystems in comparison to large ocean areas may require larger adaptive capacities for freshwater cyanobacteria.

Overall, this work opens new perspectives in cyanobacterial studies related to evolution and adaptation and life style duality in single genera. The first report here of a nitrogen-fixing Planktothrix strain challenges the commonly known features of this genus and should encourage investigations on distribution and evolution of diazotrophy in the cyanobacterial phylum as well as raise questions on the ecological implications of such finding. The wider potential for natural products of this genus should lead to the survey and monitoring of more potentially hazardous compounds, especially in understudied benthic blooms.

Methods

Description of the sequenced strains and of the DNA isolation

Six axenic PCC strains of Planktothrix spp. were grown in BG11 media at 18 °C for PCC 7821, and at 22 °C for all others (Table 1). These strains isolated at different geographical locations displayed different life styles in culture conditions such as planktic, biphasic and benthic (Fig. S1). The cultures to obtain biomass for genomic DNA isolation or/and electron microscopy capitation of the gas vesicules are detailed in the supplementary information.

Estimation of the growth under different nitrogen concentrations

For growth under nitrogen deprivation, actively growing cultures were harvested by gentle centrifugation prior to be transferred in four BG11 differing in nitrate availability (ca 18 mM to 9 mM, 2 mM and none). Three successive transfers were performed. In addition, cultures in BG11o showing depigmentation or discoloration were transferred in BG112 to test their survival with supplemented nitrate. We compared also the effect of light/dark cycle to continuous light on the nitrogen fixation on cultures grown in BG11 and BG11o. Finally, the diazotrophic Cyanothece sp. PCC 7822 was included as positive control for nitrogen fixation39.

Sequencing and assembling methods

The whole genome sequences PCC 7805 and PCC 7821 were obtained using next generation sequencing technologies. A 454 library was constructed and around 20-fold coverage of GSflx (www.roche.com) reads were assembled using Newbler (www.roche.com). Details of the assembly are resumed in the supplementary informations. For each genomic DNA of PCC 8927, PCC 9214, PCC 9631 and PCC 11201, a mate-paired library with around 10 kb insert size was performed. The sequencing was realized on Illumina MiSeq device (producing 250 nt length for each fragment extremity) leading to ~150-fold coverage per genome. The read data were assembled using Velvet (https://www.ebi.ac.uk). To reduce the number of undetermined bases, GapCloser (http://soap.genomics.org.cn/soapdenovo.html) was performed on scaffolds with a size >2 kb. The assembly data of all strains were integrated into the Microscope platform for automatic annotation (http://www.genoscope.cns.fr/agc/microscope). In silico analyses of the new genomes were performed in MicroScope platform40 and resumed in the supplementary information.

Phylogenetic reconstruction and ANI analysis

The species tree was generated by a concatenation of 586 conserved proteins selected from the phylogenetic markers previously validated for Cyanobacteria2,4,41. Ambiguous and saturated regions were removed with BMGE v1.1242 (with the gap rate parameter set to 0.5). A Maximum-Likelihood phylogenetic tree was generated with the alignment using RAxML v7.4.343 with the LG amino acid substitution model. The genomes of Lyngbya sp. CCY 9616 and Arthrospira sp PCC 8005 were used as outgroup in order to root the phylogenetic tree with the closest relatives as indicated in the extended phylogenetic tree (Fig. S4). The phylogenetic tree was displayed and annotated using the interactive tree of life (iTOL) online tool44. Nif phylogeny was built on the protein sequences of NifB, NifD, NifH, NifS and NifU and performed with the SeaView package (version 4.6.1)45. Briefly, genes were independently aligned using MUSCLE (vers. 3.5)46. The alignments were concatenated and filtered to remove all invariable sites. The phylogenetic analysis was performed using PhyML for Maximum Likelihood47 with a GTR (generalise time-reversible) substitution model and bootstrap analysis (1000 replicates). The GvpC phylogeny was conducted similarly to the Nif phylogeny.

Average nucleotide identity (ANI) was computed using the Jspecies package48. Whole genome similarity calculation were identical regardless the ANI algorithm used (ANIb based on blast algorithm and ANIm based on MUMmer algorithm).

Gas vesicle protein C gene analysis

The GvpC sequences of Planktothrix were aligned with clustal–omega (http:// www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo/). Manual search for repeated structure in each protein sequences was performed by using the consensus 33 amino acid repeats described in GvpC of Anabaena sp. (HKdLekdtQeFLSdTAkeRmAQAkeQAeqLhqF) and of Calothrix sp. (HKeLqetsQqFLSaTAqaRiAQAekQAqeLlaF)49. The repeats of GvpC proteins were analyzed with Weblogo (http://weblogo.berkeley.edu/logo.cgi) and compararison of GvpC was performed by BLAST analysis (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi).

Tolytoxin detection

Tolytoxin detection was performed by HPLC-MS and NMR as described for the characterization of this compound in Scytonema sp. PCC 1002321. NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Avance III spectrometer equiped with a cold probe at 500 MHz for 1H NMR. Chemical shifts were referenced to the solvent peaks at δH 2.05 for acetone-d6. LC-ESI mass spectrometry was performed on a Thermo Scientific Q Exactive mass spectrometer.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Pancrace, C. et al. Insights into the Planktothrix genus: Genomic and metabolic comparison of benthic and planktic strains. Sci. Rep. 7, 41181; doi: 10.1038/srep41181 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thanks the following people for assistance in aspects of the project S. Wood for the strain VUW25 from New Zealand, C. Djediat for TEM, T. Rouxel for photographies of the culture appearances. This work was partially supported by the French National Research Agency under Contract N° ANR-15-CE34-0002-02, by incentive credits from INRA (France) and the Conny Maeva Charitable Foundation. The Pasteur Culture Collection of Cyanobacteria was supported by the Institut Pasteur. CP was supported by the Ile-de-France ARDoC Grant for PhD. All cyanobacteria represented by genomes sequenced of this study are available from the Institut Pasteur (http://cyanobacteria.web.pasteur.fr/).

Footnotes

Author Contributions J.F.H. and M.G. initiated the project. C.P., M.A.B., R.U., A.C., T.S., J.P., V.B., J.F.H. and M.G. performed the experiment and analyzed data. All authors were involved in writing the paper and had final approval of the manuscript.

References

- Bothe H., Tripp H. J. & Zehr J. P. Unicellular cyanobacteria with a new mode of life: the lack of photosynthetic oxygen evolution allows nitrogen fixation to proceed. Arch Microbiol 192, 783–790, doi: 10.1007/s00203-010-0621-5 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calteau A. et al. Phylum-wide comparative genomics unravel the diversity of secondary metabolism in Cyanobacteria. BMC Genomics 15, 977, doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-977 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey C. C., Ibelings B. W., Hoffmann E. P., Hamilton D. P. & Brookes J. D. Eco-physiological adaptations that favour freshwater cyanobacteria in a changing climate. Water Res 46, 1394–1407, doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2011.12.016 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schirrmeister B. E., Antonelli A. & Bagheri H. C. The origin of multicellularity in cyanobacteria. BMC Evol Biol 11, 45, doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-11-45 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Baracaldo P. Origin of marine planktonic cyanobacteria. Sci Rep 5, 17418, doi: 10.1038/srep17418 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih P. M. et al. Improving the coverage of the cyanobacterial phylum using diversity-driven genome sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110, 1053–1058, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1217107110 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komarek J. & Anagnostidis K. Cyanoprokaryota. Part 2: Oscillatoriales Vol. 19/2, 759 (Spektrum Akademischer Verlag, 2005). [Google Scholar]

- Anagnostidis K. & Komárek J. Modern Approach to the Classification System of Cyanophytes. 3—Oscillatoriales. Algolog. Stud. 50–53, 327–472 (1988). [Google Scholar]

- Wood S. et al. Identification of a benthic microcystin-producing filamentous cyanobacterium (Oscillatoriales) associated with a dog poisoning in New Zealand. Toxicon 55, 897–903 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaget V., Welker M., Rippka R. & de Marsac N. T. A polyphasic approach leading to the revision of the genus Planktothrix (Cyanobacteria) and its type species, P. agardhii, and proposal for integrating the emended valid botanical taxa, as well as three new species, Planktothrix paucivesiculata sp. nov.ICNP, Planktothrix tepida sp. nov.ICNP, and Planktothrix serta sp. nov.ICNP, as genus and species names with nomenclatural standing under the ICNP. Syst Appl Microbiol 38, 141–158, doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2015.02.004 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyra C., Laamanen M., Lehtimaki J. M., Surakka A. & Sivonen K. Benthic cyanobacteria of the genus Nodularia are non-toxic, without gas vacuoles, able to glide and genetically more diverse than planktonic Nodularia. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 55, 555–568, doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.63288-0 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beard S. J., Davis P. A., Iglesias-Rodríguez D., Skulberg O. M. & Walsby A. E. Gas vesicle genes in Planktothrix spp. from Nordic lakes: strains with weak gas vesicles possess a longer variant of gvpC. Microbiology 146, 2009–2018 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker S. J., Hayes P. K. & Walsby A. E. Different gvpC length variants are transcribed within single filaments of the cyanobacterium Planktothrix rubescens. Microbiology 151, 59–67 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bright D. & Walsby A. The relationship between critical pressure and width of gas vesicles in isolates of Planktothrix rubescens from Lake Zürich. Microbiology 145, 2769–2775 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsby A. E. Stratification by cyanobacteria in lakes: a dynamic buoyancy model indicates size limitations met by Planktothrix rubescens filaments. New Phytol 168, 365–376, doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2005.01508.x (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briand E. et al. Temporal variations in the dynamics of potentially microcystin-producing strains in a bloom-forming Planktothrix agardhii (Cyanobacterium) population. Appl Environ Microbiol 74, 3839–3848, doi: 10.1128/AEM.02343-07 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurmayer R. & Gumpenberger M. Diversity of microcystin genotypes among populations of the filamentous cyanobacteria Planktothrix rubescens and Planktothrix agardhii. Mol Ecol 15, 3849–3861, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2006.03044.x (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rounge T. B., Rohrlack T., Kristensen T. & Jakobsen K. S. Recombination and selectional forces in cyanopeptolin NRPS operons from highly similar, but geographically remote Planktothrix strains. BMC Microbiol 8, 141, doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-8-141 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rounge T. B., Rohrlack T., Nederbragt A. J., Kristensen T. & Jakobsen K. S. A genome-wide analysis of nonribosomal peptide synthetase gene clusters and their peptides in a Planktothrix rubescens strain. BMC Genomics 10, 396, doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-396 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rounge T. B., Rohrlack T., Tooming-Klunderud A., Kristensen T. & Jakobsen K. S. Comparison of cyanopeptolin genes in Planktothrix, Microcystis, and Anabaena strains: evidence for independent evolution within each genus. Appl Environ Microbiol 73, 7322–7330 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueoka R. et al. Metabolic and evolutionary origin of actin-binding polyketides from diverse organisms. Nat Chem Biol 11, 705–712, doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1870 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tooming-Klunderud A. et al. From green to red: horizontal gene transfer of the phycoerythrin gene cluster between Planktothrix strains. Appl Environ Microbiol 79, 6803–6812, doi: 10.1128/AEM.01455-13 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen G., Goesmann A. & Kurmayer R. Elucidation of insertion elements carried on plasmids and in vitro construction of shuttle vectors from the toxic cyanobacterium Planktothrix. Appl Environ Microbiol 80, 4887–4897 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsujimoto R., Kamiya N. & Fujita Y. Transcriptional regulators ChlR and CnfR are essential for diazotrophic growth in nonheterocystous cyanobacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111, 6762–6767, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1323570111 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vestola J. et al. Hassallidins, antifungal glycolipopeptides, are widespread among cyanobacteria and are the end-product of a nonribosomal pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111, E1909–1917, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1320913111 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leikoski N. et al. Genome mining expands the chemical diversity of the cyanobactin family to include highly modified linear peptides. Chem Biol 20, 1033–1043, doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2013.06.015 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziemert N. et al. Diversity and evolution of secondary metabolism in the marine actinomycete genus Salinispora. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111, E1130–1139 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humbert J. F. et al. A tribute to disorder in the genome of the bloom-forming freshwater cyanobacterium Microcystis aeruginosa. PLoS One 8, e70747, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070747 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beard S. J., Handley B. A., Hayes P. K. & Walsby A. E. The diversity of gas vesicle genes in Planktothrix rubescens from Lake Zürich. Microbiology 145, 2757–2768 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranz S. A., Eichner M. & Rost B. Interactions between CCM abd N2 fixation in Trichodesmium. Photosynthesis Research 109, 73–84 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brauer V. S. et al. Competition and facilitation between the marine nitrogen-fixing cyanobacterium Cyanothece and its associated bacterial community. Front Microbiol 5, 795, doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00795. (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz-Garcia J. & Ares S. Formation and maintenance of nitrogen-fixing cell patterns in filamentous cyanobacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 113, 6218–6223 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abed R. M. M., Palinska K. A., Camoin G. & Golubic S. Common evolutionary origin of planktonic and benthic nitrogen-fixing oscillatoriacean cyanobacteria from tropical oceans. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 260, 171–177 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman B., Gallon J. R., Rai A. N. & Stal L. J. N2 fixation by non heterocystous cyanobacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev 19, 139–185 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Latysheva N., Junker V. L., Palmer W. J., Codd G. A. & Barker D. The evolution of nitrogen fixation in cyanobacteria. Bioinformatics 28, 603–606, doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts008 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufresne A. et al. Unraveling the genomic mosaic of a ubiquitous genus of marine cyanobacteria. Genome Biol 9, R90, doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-5-r90 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopf M. et al. Comparative genome analysis of the closely related Synechocystis strains PCC 6714 and PCC 6803. DNA Res. 21, 255–266 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penn K. et al. Genomic islands link secondary metabolism to functional adaptation in marine Actinobacteria. Isme J 3, 1193–1203 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandyopadhyay A. et al. Novel metabolic attributes of the genus Cyanothece, comprising a group of unicellular nitrogen-fixing Cyanothece. MBio 2, doi: 10.1128/mBio.00214-11 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallenet D. et al. MicroScope--an integrated microbial resource for the curation and comparative analysis of genomic and metabolic data. Nucleic Acids Res 41, D636–647, doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1194 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soo R. M. et al. An expanded genomic representation of the phylum cyanobacteria. Genome Biol Evol 6, 1031–1045, doi: 10.1093/gbe/evu073 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Criscuolo A. & Gribaldo S. BMGE (Block Mapping and Gathering with Entropy): A new software for selection of phylogenetic informative regions from multiple sequence alignments.. BMC Evol Biol 10, 201 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis A. RAxML-VI-HPC: Maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics 22, 2688–2690 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letunic I. & Bork P. Interactive tree of life (iTOL) v3: An online tool for the display and annotation of phylogenetic and other trees. Nucleic Acids Res 44, W242–245 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouy M., Guindon S. & Gascuel O. SeaView version 4: A multiplatform graphical user interface for sequence alignment and phylogenetic tree building. Molecular Biology and Evolution 27, 221–224 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res 32, 1792–1797 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guindon S. et al. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst Biol 59, 307–321, doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syq010 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter M. & Rossello-Mora R. Shifting the genomic gold standard for the prokaryotic species definition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106, 19126–19131, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906412106 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsby A. E. Gas vesicles. Microbiology Reviews 58, 94–144 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.