Abstract

Background:

Cervical cytology is the best single method for large screening of the population in identifying precancerous lesions of the uterine cervix.

Aim:

To estimate the frequency of human papillomavirus (HPV) positivity in a group of Albanian women, the prevalence of vaginal coinfections, and the relationship of coinfections with HPV, as well as their role in metaplasia or cervical intraepithelial lesions (CIN).

Materials and Methods:

In this retrospective study, 2075 vaginal smears were examined. The Papanicolaou stain was used for all slides. The New Bethesda System 2001 was used for the interpretations of the smears. Data analysis was completed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 19.0.

Results:

Prevalence of HPV positivity was 43.9% with an average age of 35.48 ± 9.27 years. Candida coinfection resulted in 57.8% of HPV positive women with a significant relationship between them. Gardnerella coinfection resulted in 36 (23%), mixed flora in 34 (8%), and Trichomonas vaginalis in 50% of HPV positive woman. Among the women with positive HPV, 19% had CIN, 8% had metaplasia, and 1% had metaplasia and CIN; 9% of the women with HPV had CIN1 and one of the coinfections.

Conclusions:

There is a strong relationship between CIN1 and HPV positivity as well as between CIN1 and coinfections. HPV infection is a major factor contributing to metaplasia, and bacterial coinfections in HPV positive women have a statistically significant impact in the development of metaplasia.

Keywords: CIN, coinfections, HPV infection, inflammation, metaplasia

Introduction

Intraepithelial neoplastic lesions of the uterine cervix (CIN) represent a multifactorial pathology, where human papillomavirus (HPV) is implicated as the major causative agent in the development of cervical cancer.[1] Nowadays, it is clearly stated that infection with HPV is necessary for the development of CIN and cervical cancer (CC).[2] High risk HPV infection is essential but not sufficient for the transformation of epithelial cells.[3,4] Other exogenous and endogenous factors working together with HPV increase the risk of progression from cervical lesions to CC.[5] Studies in high grade intraepithelial squamous lesions (HSIL) and CC in HPV positive women have clearly concluded that factors such as multiparity, smoking, prolonged use of oral contraceptives, and herpes simplex 2 virus infection may modulate the risk of progression from HPV infection to HSIL/CC.[6] In evaluating the cofactors and their role in the development of cervical lesions, there is also a relationship between HPV infection and coinfections with Gardnerella vaginalis, Candida, Chlamydia, and Trichomonas.[7]

Over 90% of women with cervical cancer are HPV positive.[8] Persistence of the HPV infection as well as viral DNA insertion in epithelial cells are the main factors leading to high grade dysplasia with the potential of progression to carcinoma in situ and invasive cancer.[9] Coinfections in HPV positive women are thought to interfere in the natural evolution of cellular lesions caused by the virus.[10]

Another known risk factor in the pathogenesis of cancer is chronic inflammation. According to many recent clinical studies, chronic inflammation is seen as a “promoter” of carcinogenesis by inducing proliferation, recruiting inflammatory cells, increasing the production of ROS leading to DNA damage, and inhibiting DNA reparation.[11] Cellular inflammatory changes, such as metaplasia during inflammatory cervicitis induced by sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), is thought to make the cervical cells more susceptible to mutations by activating oncogenes, inactivating tumoral suppressors, or both, making cells more sensitive to HPV-induced lesions and the development of CIN.[12] The objectives of our study are to evaluate the frequency of HPV positivity in a group of 2075 Albanian women who are recommended for the Pap test by the gynecologist, analyze the average age of HPV infected women, the frequency of vaginal coinfections in HPV positive women, and evaluate the relationship between HPV positivity coinfections, metaplasia, and CIN using traditional methods such as Pap test, colposcopy, and histopathology.

Materials and Methods

In our study we included a total of 2075 Albanian woman who were referred to the Morphology Department by the gynecologist for Pap test examination. A detailed history for each patient was included in the file from the gynecologist and was reviewed before the examination. The study was conducted over a 5-year period (March 2008 to February 2013). Data were anonymously treated and the study was performed in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration. The approval of the Ethical Committee was requested and granted.

The material was collected from exo and endocervix according to recent standards and recommendations using an Ayre spatula and was immediately spread into a thin layer on a slide. After fixation with 96% ethanol, the smears were stained using the Papanicolaou technique. The slides were observed using the OPTICA B-600T light microscope at a 20 × 40 magnification.

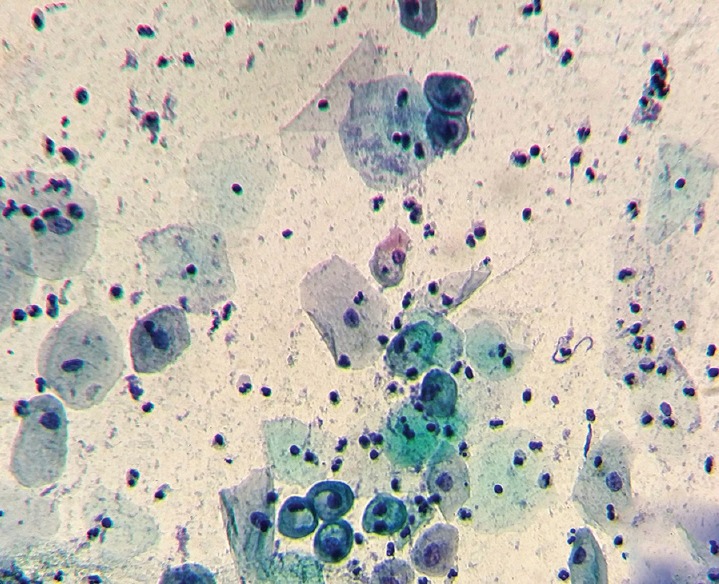

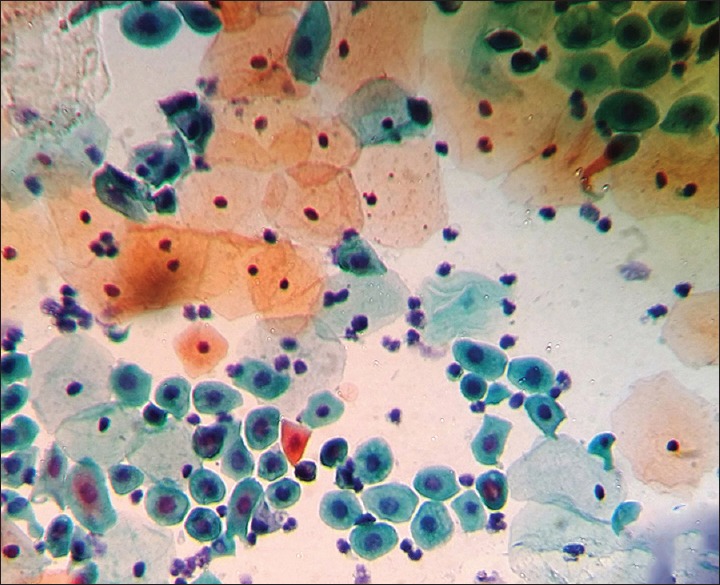

All women who were menstruating, those who were pregnant, and those who were diagnosed and treated for CIN prior to our examination were excluded from the study. The study was retrospective and was based on the evidence of cervical smears archived together with corresponding answers of each cytopathologic examination. The smears were interpreted using the New Bethesda System 2001. The diagnosis of HPV was based on Schneider criteria (classic koylocytosis) [Figure 1] and the presence of 9 non-classical minor criteria.[13] Diagnosis of CIN was based on the nuclear alterations of the superficial squamous layer. Positivity of Candida was based on the typical micellar structure. Positivity of Gardnerella vaginalis was based on the identification of “clue cells” and the tiny formations of rods. Positivity of Trichomonas vaginalis was based on the protozoan cytological discovery (squamous inflammatory cells named “canonball” with perinuclear halo, reactive nuclear changes, and attachment of pathogenic microorganisms into the squamous cells).

Figure 1.

Photomicrograph of a case showing koilocytes, a sign of HPV infection (Pap, × 400)

In the statistical analysis, continuous data was presented as mean and standard deviation. Discrete data was presented as absolute value and percentage. Random relationships between variables were analyzed through binary logistic regression. For every variable, the odds ratio (OD) and credible interval 95% (CI 95%) were presented. Values of P ≤ 5% were considered significant. Data analysis was completed using the statistical package, SPSS 19.0 (Statistical Package for Social Sciences).

Results

The prevalence of the HPV positivity in our group was 43.9% (CI 95%: 41.1–45.6) (910 out of 2075 cases). Average age of the HPV positive women was 35.48 ± 9.27 years, with a range of 17–80 years old. The frequency of the positivity for HPV in specific age groups (18–25, 25–35, 35–45, 45–55, and over 55 years old) is the highest at the 25–35 age group (43.6%).

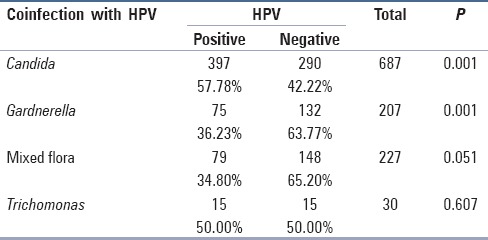

Among the group of women included in the study, 687 (33.5%) had positive cytology for Candida [Table 1]. In this group, 397 (57.8%) women had positive cytology for HPV at the same time. There is an important statistical relation between the two (P = 0.001).

Table 1.

Number of cases with positive HPV and other coinfections

Among all the women included in the study, 207 (9.9%) had positive cytology for Gardnerella vaginalis. Among this group, 75 (36.23%) had positive cytology for HPV at the same time.

Among all the women included in the study, 227 (10.9%) had positive cytology for mixed flora. Among this group, 79 (34.8%) had positive cytology for HPV at the same time.

Among all the women included in the study, 30 or 1.4% had positive cytology for Trichomonas vaginalis. Among this group, 15 (50%) at the same time had positive cytology for HPV.

In 60.2% of women with positive cytology for HPV, there was at least one coinfection with one of the pathogens mentioned above.

Among our cases of women with positive cytology for HPV, 144 (15.8%) had metaplasia, 173 (19%) had CIN, and 19 (2.1%) had both metaplasia and CIN.

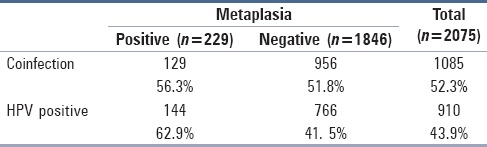

When we examined metaplasia and intraepithelial lesions (CIN) among the group of women included in the study, we noticed that the total number of women with metaplasia was 229 (11.0%) whereas the number of women with CIN was 233 (11.2%).

Among 229 women with metaplasia, 129 (56.3%) [Table 2] had positive cytology for HPV, and among this group, 73 women (56.6%) were at the same time positive for infections coexisting with HPV.

Table 2.

The relationship between metaplasia, positive cytology for HPV and coinfections

In women with positive cytology for HPV and metaplasia, 56.6% also had positive cytology for at least one of the coinfections.

Logistic regression showed that coinfection is an important factor causing metaplasia in the presence of HPV positivity. Coinfection alone does not seem to be an important factor. There is a strong relationship between metaplasia and the cases with positive cytology for HPV, whereas there is no significant relationship between metaplasia and coinfections (P = 0.665).

We can conclude that women with positive cytology for HPV had at the same time one of the vaginal coinfections, had 3.8 times more chance of developing metaplasia, compared to those who had no coinfections (OD = 3. 8; CI 95%: 2.75–5.69).

Among the 233 women with CIN1, 173 (74.2%) had positive cytology for HPV, and 82 (47.4%) were positive for one of the coinfections.

There was a strong connection between CIN1 and positivity of HPV, as well as between CIN1 and coinfection. When coinfection was analyzed with HPV positivity, the role of coinfection became weaker. There was no statistical significance between CIN1 and coinfection (P = 0.138).

From this analysis, we can see that women with positive cytology for HPV and at the same time positive for coinfections did not have a strong connection with CIN1 (OD = 1.27; CI 95%: 0.67–3.39).

Discussion

The cytological examination is important in identifying the cervicovaginal infections. For example, the identification of Candida, Gardnerella, and especially Trichomonas vaginalis is most of the time the responsibility of the cytopathologist. There are studies showing that cytology has a greater accuracy than biopsy.[14] These sexually transmitted infections have become the object of many studies and research teams all over the world; studies have shown a connection with cervical cancer when they are coexisting with HPV infection.[7,9] In recent studies, in addition to the Pap smear examination and the age of the female patient, there is significant emphasis in HPV DNA testing. This test, combined with the Pap smear examination, shows a sensitivity of 96–100% in diagnosing CIN or CC. However, the HPV DNA test is not recommended as a primary tool for screening women younger than 30 years old because in most of them the HPV infection self-heals spontaneously in a short time.[15,16] Based on the fact that cancerous lesions are often related with the persistence of HPV and not just infection with the virus, continuous retesting for HPV DNA is an important step in preventing CC.[9] HPV DNA testing is recommended for women of all ages when the Pap smear results in ASCUS, and is a good follow-up test for woman with positive colposcopy or cytology.[17] Despite the high sensitivity and selectivity of HPV DNA testing in combination with cytology, in developing countries, it remains difficult to apply because of the high cost of the examination.[18] At the same time, we have to realize that the massive screening programs using cervical cytology in many countries have reduced the incidence and mortality of cervical cancer to 43% and 46%, respectively. In countries with low income, where the screening programs using HPV DNA are difficult to apply, there is still much to be done using conventional cytology (Pap smear) in reducing the incidence and mortality of CC.[19]

In our study, the women examined represented a target group recommended for Pap smear examination after being examined by a gynecologist and were not a random group of women without signs or symptoms. Therefore, the cytological positivity of HPV infection in our study was as high as 43%. In other studies, with screening purposes, the numbers are of course lower, whereas in studies conducted on sexually active females with gynecologic symptoms, the numbers are very high.[20] Our study confirms a high incidence of HPV infection as the most common STD in many countries with the highest distribution in age groups with an active sexual life. It is estimated that the incidence of new infections in the United States ranges from 1 million to 5.5 million per year, and the prevalence is estimated to be as high as 20 million.[21]

Discussing the distribution of HPV positivity in different age groups, it is interesting to notice that in our country there is a similar age group distribution with the countries of Eastern Europe. This is different from the distribution in other parts of the world where the dominant age group is under 25 years old.[16] The prevalence of HPV infection is very low in women over 60 whereas the incidence of high grade cervical lesions increases with age.[22] In countries of Eastern Europe, as in our study, we find a higher number of positive women in the age group of 25–30 years old.[23] This is the age where preventive efforts and policies should be focused to reduce the incidence of CC.

Our other objective in this study was to examine the relation between HPV positivity and vaginal coinfections and their role in the pathogenesis of CC. We know that the intraepithelial neoplastic lesions of the uterine cervix are multifactorial in their pathogenesis.[24] We also know that HPV is the primary etiologic agent leading to malign transformation of the epithelial cells. Yet, the manner in which the latent infection progresses to CC remains unknown. Carcinogenesis remains a complex and gradual process where the intervention of other factors is necessary to create the mutation leading to the formation of the malign cell clone undergoing rapid proliferation. The hypothesis that HPV is necessary but not sufficient in developing the CC is considered statistically correct.

There are several studies, especially in developing countries, suggesting a clear and statistically significant relationship between the HPV positivity and vaginal coinfections such as bacterial vaginosis, Candida albicans, Chlamydia, Trichomonas vaginalis, etc., At the center of carcinogenesis remains the infection with high risk types of HPV (16 and 18), the persistence of the viral infection and the insertion of the viral DNA in the epithelial cells.[2] In a molecular level, the mechanism leading to cervical cancer from HPV infection is connected with the viral proteins E6 and E7.[25] Coinfections with HPV are thought to intervene in the natural history of the HPV infection as well as in the development of the lesions caused by the virus itself.[26]

Among the women who tested positive for HPV, 36.23% had positive cytology for bacterial vaginosis, 57.78% had positive cytology for Candida albicans, 50% had positive cytology for Trichomonas vaginalis, and 34.80% had positive cytology for mixed flora [Table 1].

According to our results, there is also a strong connection between the positivity of HPV and CIN 1 as well as between CIN 1 and coinfection. When the coinfection is analyzed together with the positivity of HPV, the role of coinfection is diminished (there is no statistically significant connection between CIN 1 and coinfection) (P = 0.138).

This important result shows that these sexually transmitted infections could help HPV infected cells to develop CIN. A study from Scandinavia showed that bacterial vaginosis increased 3.57% of the incidence of CIN whereas another study showed that CIN 1 was found in 5% of the study population without coinfection and only 1.4% in the group without coinfection.[27]

Bacterial vaginosis is associated with a reduction in the vaginal fluid and the blocking of the leukocyte protease inhibitor (SLPI). Another hypothesis in the relation of bacterial vaginosis with the process of carcinogenesis is the release of lytic enzymes from the bacteria leading to the loss of the mucous layer protecting the vagina. This leads to microabrasions of the epithelia, increasing the virulence and adhesiveness of HPV, thus promoting the integration of the viral genome in the epithelia of the transformation zone.[28]

It is also seen that the incidence of CIN increases from the coinfection with Trichomonas vaginalis, which can be very difficult to identify by using only cytological methods.[14] Vaginitis from Trichomonas infects 3–5 million women in USA with a prevalence of 3% in those of the reproductive age.[28] In another massive screening among a group of Dutch women and a group of migrant women in Holland related to the prevalence of Gardnerella vaginalis, Trichomonas, and Candida, there was an increased risk of squamous abnormalities in the presence of the high levels of Gardnerella and Trichomonas in the migrant women.[29]

In our study, we have also aimed at evaluating metaplasia, which is a direct consequence of the inflammation caused by the coinfection of HPV with the other vaginal infections. In our study metaplasia, including the atypical type, was found in 11% of the cases (229 women) while CIN 1 in 11.5% of the cases (233 women) [Table 2]. From all the cases with metaplasia, more than half had cytological positivity for HPV (56.3%) and 56% of them tested positive at the same time for coinfection. By statistical analysis, we found that infection with HPV is a major factor leading to metaplasia, which is a fertile terrain for cervical cancer. We also found that the vaginal coinfections have an important role in the development of metaplasia. According to the logistic regression, we noted that women with HPV and coinfection have a 3.8 times higher chance of having metaplasia compared to the ones with only HPV infection.

Related to CIN, the cases with positive cytology for HPV and CIN1 are 173 (74.2%), which shows an important relationship between HPV infection and CIN. When it comes to coinfections, we see that 82 women out of 173 have at the same time CIN, HPV and vaginal coinfection. Using logistical regression, we find a direct connection between coinfection and CIN, but there is no statistically significant connection between HPV with coinfections in the development of CIN.

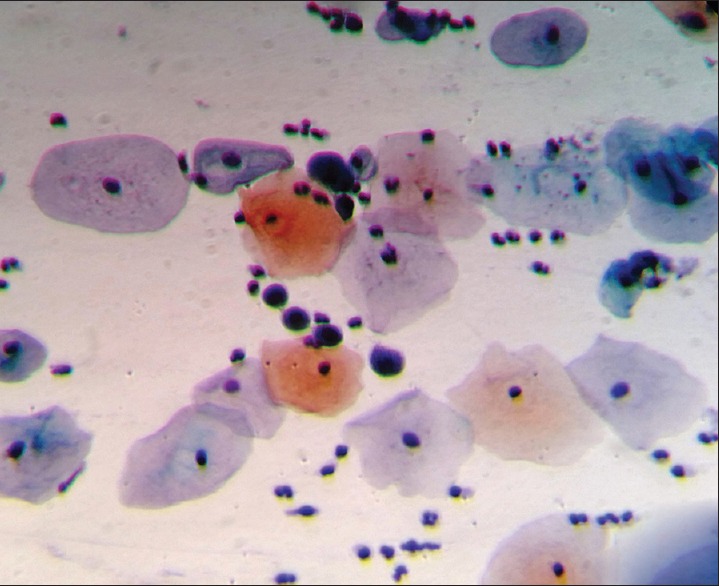

After the statistical analysis, we can see that coinfection is an important factor leading to metaplasia in the presence of HPV and that the vaginal infection alone is not an important factor leading to metaplasia. According to this analysis, women with a positive cytology for HPV and vaginal bacterial infection [Figures 2 and 3] at the same time have a 3.8 times more chance of developing metaplasia compared to those who do not have these coinfections.

Figure 2.

Photomicrograph from a case showing atypical immature squamous metaplasia in a woman with HPV infection. Cells showing large hyperchromatic nuclei (Pap, × 400)

Figure 3.

Photomicrograph showing cellular alterations caused by HPV infection. Immature squamous metaplasia (Pap, × 400)

Conclusion

Considering the limited possibilities at our disposal in order to examine the type of HPV through genetic testing, we conclude that the use of cervical cytology (Pap smear) is the best method for massive screening of the population in identifying the precancerous lesions and almost completely preventing cervical cancer. The success achieved using this method in many developed countries before the discovery of the HPV DNA testing or HPV vaccine, is a major argument leading to the conclusion that the correct use and application of the Pap test could totally prevent the cervical cancer in our society.[19]

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Gonzalez Intxaurraga MA, Stankovic R, Sorli R, Trevisan G. HPV and carcinogenesis. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2002;11:95–9. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burd EM. Human Papillomavirus and Cervical Cancer. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2003;16:1–17. doi: 10.1128/CMR.16.1.1-17.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Castellsague X, Bosch FX, Munoz N. Environmental co-factors in HPV carcinogenesis. Virus Res. 2002;89:191–9. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(02)00188-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Castellsague X, Munoz N. Chapter 3: Co-factors in human papilloma virus carcinogenesis. Role of parity, oral contraceptives, and tobacco smoking. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2003;31:20–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Denis F, Hanz S, Alain S. Clearance, persistence and recurrence of HPV infection. Gynecol Obstet Fertil. 2008;36:430–40. doi: 10.1016/j.gyobfe.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daling JR, Madeleine MM, McKnight B, Carter JJ, Wipf GC, Ashley R, et al. The relationship of human papillomavirus-related cervical tumors to cigarette smoking, oral contraceptive use, and prior herpes simplex virus type 2 infection. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1996;5:541–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tao L, Han L, Li X, Gao Q, Pan L, Wu L, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for cervical neoplasia: A cervical cancer screening program in Beijing. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:1185. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walboomers JM, Jacobs MV, Manos MM, Bosch FX, Kummer JA, Shah KV, et al. Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide. J Pathol. 1999;189:12–9. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199909)189:1<12::AID-PATH431>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luhn P, Walker J, Schiffman M, Zuna RE, Dunn ST, Gold MA, et al. The role of co-factors in the progression from human papillomavirus infection to cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;128:265–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roeters AM, Boon ME, van Haaften M, Vernooij F, Bontekoe TR, Heintz AP. Inflammatory events as detected in cervical smears and squamous intraepithelial lesions. Diagn Cytopathol. 2010;38:85–93. doi: 10.1002/dc.21169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deivendran S, Marzook KH, Radhakrishna Pillai M. The Role of Inflammation in Cervical Cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2014;816:377–99. doi: 10.1007/978-3-0348-0837-8_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wan F, Miao X, Quraishi I, Kennedy V, Creek KE, Pirisi L. Gene expression changes during HPV-mediated carcinogenesis: A comparison between an in vitro cell model and cervical cancer. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:32–40. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schneider V. Microscopic diagnosis of HPV infection. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1989;32:148–56. doi: 10.1097/00003081-198903000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Howell LP, Darragh TM, Souers RJ, Thomas N, Moriarty AT. Identification of Trichomonas vaginalis in different Papanicolaou test preparations: Trends over time in the College of American Pathologists Educational Interlaboratory Comparison Program. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:1043–6. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2012-0036-CP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Castle PE, Rodriguez AC, Burk RD, Herrero R, Wacholder S, Alfaro M, et al. Short term persistence of human papillomavirus and risk of cervical precancer and cancer: Population based cohort study. BMJ. 2009;339:b2569. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moscicki AB. Impact of HPV infection in adolescent populations. J Adolesc Health. 2005;37:S3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moyer AV, LeFevre ML, Siu AL, Bibbins-Domingo K, Curry SJ, Flores G, et al. Screening for Cervical Cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2012;19(156):880–91. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-12-201206190-00424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Drain PK, Holmes KK, Hughes JP, Koutsky LA. Determinants of cervical cancer rates in developing countries. Int J Cancer. 2002;100:199–205. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Waggoner SE. Cervical cancer. Lancet. 2003;361:2217–25. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13778-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Winer RL, Lee SK, Hughes JP, Adam DE, Kiviat NB, Koutsky LA. Genital human papillomavirus: Infection incidence and risk factors in a cohort of female university students. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157:218–26. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Revzina NV, Diclemente RJ. Prevalence and incidence of human papillomavirus infection in women in the USA: A systematic review. Int J STD AIDS. 2005;16:528–37. doi: 10.1258/0956462054679214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schlecht NF, Platt RW, Duarte-Franco E, Costa MC, Sobrinho JP, Prado JC, et al. Human papillomavirus infection and time to progression and regression of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:1336–43. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dillner J. Trends over time in the incidence of cervical neoplasia in comparison to trends over time in human papilomavirus infection. J Clin Virol. 2000;19:7–23. doi: 10.1016/s1386-6532(00)00126-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Misra JS, Das V, Srivastava AN, Singh U, Chhavi Role of Different Etiological Factors in Progression of Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia. Diagn Cytopathol. 2006;34:682–5. doi: 10.1002/dc.20516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Howie HL, Katzenellenbogen RA, Galloway DA. Papillomavirus E6 proteins. Virology. 2009;384:324–34. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McMurray HR, Nguyen D, Westbrook TF, McAnce DJ. Biology of human papillomavirus. Int J Exp Pathol. 2001;82:15–33. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2613.2001.00177.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Platz-Christensen JJ, Sundström E, Larsson PG. Bacterial vaginosis and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1994;73:586–8. doi: 10.3109/00016349409006278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sutton M, Sternberg M, Koumans EH, McQuillan G, Berman S, Markowitz L. The prevalence of Trichomonas vaginalis infection among reproductive-age women in the United States, 2001–2004. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:1319–26. doi: 10.1086/522532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boon ME, Holloway PA, Breijer H, Bontekoe TR. Gardnerella, Trichomonas and Candida in Cervical Smears of 58,904 Immigrants Participating in the Dutch National Cervical Screening Program. Acta Cytologica. 2012;56:242–6. doi: 10.1159/000336992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]