Abstract

Background:

The Bethesda (BSRTC) category III has been ascribed a malignancy rate of 5–15%, however, the probability of malignancy remains variable.

Aim:

To evaluate category III with respect to its rate and risk of malignancy and substratify it.

Settings and Design:

Atypia of undetermined significance/Follicular lesion of undetermined significance (AUS/FLUS) percentage, cytohistological correlation, and risk of malignancy were analyzed and substratification was done.

Material and Methods:

Category III cases over a 2-year period were analyzed retrospectively.

Statistical Analysis:

Two-tailed Fisher exact test, with a level of significance set at 0.05, was performed for data analysis.

Results:

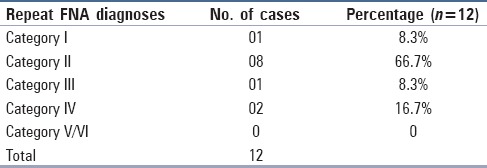

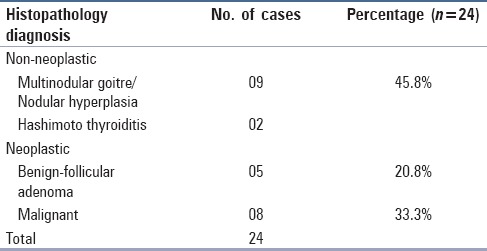

Of 1169 thyroid fine needle aspirations (FNAs), 76 (6.5%) were category III. A total of 48 patients had follow up; 24 patients underwent surgery, 12 repeat FNA, and 12 were clinically followed. Repeat FNA cytology was unsatisfactory in 8.3%, benign in 66.7%, AUS in 8.3%, and follicular neoplasm in 16.7%. Of the 24 operated, 8 (33.3%) were malignant (follicular variants of papillary thyroid carcinoma), 5 (20.8%) were follicular adenomas, and 11 (45.8%) were non-neoplastic. Among all AUS/FLUS nodules with follow-up, malignancy was confirmed in 16.7% (8/48) whereas with nodules triaged to surgery only, the malignancy rate was 33.3% (8/24). Substratification into categories of “cannot exclude PTC” and “favor benign” helped detect malignancy better, as 85.7% cases in the first subcategory (P < 0.001) and none (P < 0.02) in the last proved malignant.

Conclusion:

Though the rate of Category III in our study is in accordance to BSRTC, the risk of malignancy in AUS/FLUS nodules is higher. Substratification of AUS/FLUS may help better patient management.

Keywords: Bethesda system, Category III, substratification, thyroid nodules

Introduction

Fine needle aspiration (FNA) plays an instrumental role in the workup of a thyroid nodule by estimating the risk of malignancy and thereby assisting the rational triage of patients to surgery or observation.[1]

Cytopathology reports in the past have been ambiguous or difficult to interpret. Vague descriptors such as “atypical” and “indeterminate” have been demonstrated to confuse management. Such shortcomings were the impetus for the Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology (BSRTC), which standardized thyroid FNA results into six diagnostic categories, which has now become the accepted mode of communication between the various specialties caring for thyroid nodule patients.[1]

However, Bethesda category III has generated controversy due to inconsistent usage across different pathologists, clinicians, and institutions. Atypia of undetermined significance/Follicular lesion of undetermined significance (AUS/FLUS) was defined for use as a category of last resort, with the expectation that 7% or fewer of FNAs would receive this diagnosis. The Bethesda consensus publication estimates that such a nodule would be associated with a lower risk of malignancy (5–15%) and, in the absence of other suspicious features, could be managed with a repeat FNA.[2]

Aims and objectives

The study was undertaken with the aims of evaluating category III (AUS/FUS) with respect to its rate among total thyroid FNAs and rate of malignancy based on available follow up. The cytomorphology of these cases was studied to further substratify them and evaluate the utility of substratification.

Materials and Methods

A retrospective collection of data was conducted for all patients diagnosed with Bethesda Category III, from January 2013 to December 2014 (2 years) at the Pathology Department of a tertiary care and referral hospital.

FNA were performed under ultrasound guidance using a 25 or 26-gauge needle. Both aspiration (for cystic lesions) and nonaspiration techniques were used. Slides were stained by Giemsa and Papanicolaou stains as per standard techniques.

Study design

A standardized confidential Proforma was used to capture the information regarding patients’ clinical, radiological, cytological, and management details. Data sheet was completed for each patient.

AUS/FLUS percentage, cytological, and histological correlations, and risk of malignancy in AUS/FLUS were analyzed. The lower bound estimate was calculated by dividing the number of confirmed malignancies by the total number of AUS/FLUS nodules, whether triaged to surgery, repeat FNA, or observation. The upper bound estimate was calculated by dividing the number of confirmed malignancies by the number of AUS/FLUS nodules selected to undergo surgery.

AUS/FLUS cases with surgical follow up were reviewed blinded and substratification was performed in order to classify them into four categories on the basis of cytomorphological features. BSRTC explains 9 scenarios for category III nodules.[2] To make it simpler we divided them into following four categories by clubbing one or two scenarios together into one of these categories in accordance with study of Ho et al.[3]

AUS/FLUS – cannot exclude papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC): Focal nuclear features of PTC present in otherwise benign or sparse specimen

AUS/FLUS – cannot exclude follicular neoplasm/Hurthle cell neoplasm: Focal architectural atypia was present, e.g., microfollicular pattern, crowding, overlapping, or predominant Hurthle cell population in a sparse specimen/or clinically benign nodule

AUS/FLUS – favor benign: Benign looking specimen with abundant colloid and benign thyroid follicular cells (TFCs) with a minor population of follicular cells showing nuclear enlargement and prominent nucleoli either due to accompanying thyroiditis or degeneration or medication

AUS/FLUS – not otherwise specified (NOS): A heterogeneous group of cases that typically had rare cells with atypia, making further classification difficult. This category corresponded to the original NOS category of BSRTC

Excluded scenarios: As there was no case with atypical lymphoid cells or atypical cyst lining cells, these scenarios were excluded.

Data processing and statistical analysis were performed using Graph Pad software (Graph Pad Software, San Diego, CA). Categorical analysis was performed using a two-tailed Fisher exact test when appropriate, with a predetermined level of significance set at a P value of 0.05.

Results

A total of 1169 thyroid FNAs were done over a period of 2 years; of these, 76 were diagnosed as category III, i.e., 6.5%. There were 14 (18.4%) males and 62 (81.6%) females. Age of the patients ranged from 16 to 66 years. Mean age was 41.7 years. Maximum number of patients were in the third and fourth decade of life.

On palpation, grade (size) of the thyroid swellings was noted; maximum number of patients 46 (60.5%) had Grade II swelling, 11 (14.5%) had Grade III swelling, 13 (17.1%) had Grade I swelling, and 6 (7.9%) had Grade 0, i.e. nonpalpable swelling.

All thyroid FNAs were performed under ultrasound guidance; on ultrasonography, 53 (69.7%) patients had multiple nodules and 23 (30.2%) had a single thyroid nodule. Maximum number (38.2%) of patients with AUS/FLUS diagnosis showed hyperechoic nodules whereas 35.5% showed hypoechoic nodules. Of the 76 patients with AUS/FLUS on initial FNA, 48 had documented follow up and 28 were lost to follow up. Of these 48 patients, 24 underwent surgical resection, 14 underwent repeat FNA, and 12 patients were followed up clinically. Two patients out of the 14 repeat FNAs subsequently underwent surgery (1 diagnosed as category III and 1 as category IV on repeat aspiration). These 2 were included in surgical follow up category. The remaining 12 underwent only repeat FNA without any further surgery. On repeat FNA, maximum patients 8 (66.7%) were diagnosed as category II, 2 (16.7%) as Category IV, and 1 (8.3%) each were diagnosed as Category I and Category III [Table 1].

Table 1.

Repeat fine needle aspiration diagnoses (n=12)

On surgical follow up of the 24 cases, 8 (33.3%) were malignant, 5 (20.8%) were diagnosed as follicular adenomas, and 11 (45.8%) were benign non-neoplastic lesions. The majority of benign surgical specimens consisted of nodular hyperplasia (9/11) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Histopathology diagnoses (n=24)

Risk of malignancy among AUS/FLUS nodules triaged to surgery (upper bound estimate of malignancy) was 33.3% (8/24). All the malignancies in surgical specimens (100%) were follicular variants of papillary carcinomas. 25% (2/8) were macrofollicular variant and 75% (6/8) were microfollicular variants of papillary carcinoma.

Risk of malignancy among all AUS/FLUS nodules whether triaged to surgery, repeat FNA, or observed (lower bound estimate of malignancy) was 16.7% (8/48).

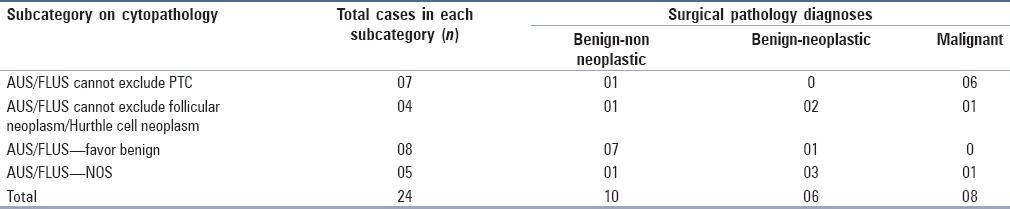

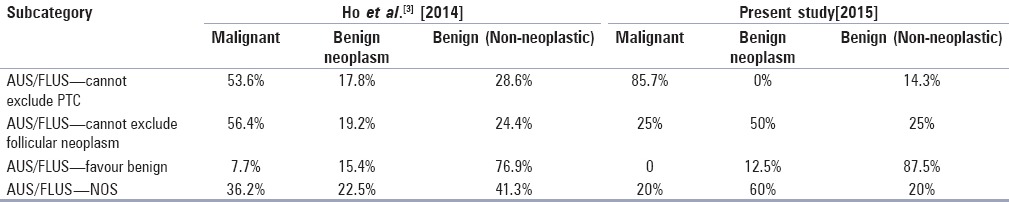

AUS/FLUS cases with surgical follow up were blind reviewed and substratification was done to classify them into various subcategories as mentioned above. Of the 24 cases, 7 cases were classified as “AUS/FLUS cannot exclude PTC,” 4 cases as “AUS/FLUS cannot exclude follicular neoplasm,” 8 cases as “AUS/FLUS-favor benign” and 5 cases as “AUS/FLUS-NOS”. Correlating with the final histopathology report, the malignancy rate in each of these categories was 85.7, 25, 0, and 20%, respectively [Table 3].

Table 3.

Substratification of AUS/FLUS cases and their surgical follow up

The risk of malignancy for atypical follicular cells subclassified as “cannot exclude PTC” was significantly higher (85.7%) than the other atypical cells, whereas in “favor benign” was significantly lower at 0% as compared to the other case scenarios of atypical follicular cells (P < 0.001 and P < 0.02, respectively). On the other hand, cases classified as “NOS” did not have a significantly different risk of malignancy when compared with “cannot exclude follicular neoplasm” cases (P = 1).

Discussion

The BSRTC has considerably facilitated the standardization of FNA reporting. However, the level of risk to be assigned to Bethesda category III nodules remains ambiguous, with some argument against the need for equivocation in a system designed to minimize it. Shi et al.[4] found that eliminating the use of AUS/FLUS as a diagnosis considerably decreased FNA sensitivity, increasing false positive and false negative rates while escalating inter- and intraobserver variability.

The study sample consisted of all category III (AUS/FLUS) thyroid patients. AUS/FLUS category comprised 6.5% of total thyroid FNAs conducted at our institution, over a period of 2 years, which is in accordance with the proposed BSRTC[2,5] rate of <7% indicating that our results are comparable with its intent. There are studies which have reported higher (>7%) AUS/FLUS rates, e.g. VanderLaan et al.[6] (10.9%), Chung et al.[7] (13%), Ratour et al.[8] (11%), Naz et al.[9] (12.7%), Wong et al.[10] (9%), and Ho et al.[3] (8%). Some studies have reported optimal rates in accordance with BSRTC, e.g., Bongiovanni et al.[11] (6.7%) and Dincer et al.[12] (2.7%).

According to The Bethesda System of Reporting Cytopathology “The risk of malignancy for an AUS nodule is difficult to ascertain because only a minority of cases in this category have surgical follow up. Those that are resected represent a selected population of patients with repeated AUS results or patients with worrisome clinical or sonographical findings. In this selected population, 20–25% of patients with AUS prove to have cancer after surgery, however, this is undoubtedly an overestimate of the risk for all AUS interpretations. The risk of malignancy is certainly lower and probably closer to 5–15%.”[2,5]

For lower bound estimate, the assumption that all observed AUS/FLUS nodules were benign is subject to verification bias, and therefore, underestimates the prevalence of malignancy. And for upper bound estimate, as nodules selected for surgery may have other clinical or ultrasonographical features that increase suspicion, this number is subject to selection bias, overestimating the prevalence of malignancy. The true prevalence is likely to lie between the lower and upper bound estimates.[3]

The observations in the present study do reflect the concerns expressed by the BSRTC as our lower bound estimate is 16.7%, however, the risk of malignancy in cases with surgical follow up (upper bound estimate) is 33.3%, which is higher than the BSRTC estimate of 25%. Rates higher than this estimate were also reported by VanderLaan et al.[6] (27.5%), Dincer et al.[12] (29.2%), and Ho et al.[3] (26.6% lower bound estimate, 38.6% upper bound estimate).

All the 8 malignant neoplasms (100%) in our study were papillary carcinomas. VanderLaan et al.[6] reported 89% as papillary carcinoma, Wong et al.[10] 93.3%, and Ho et al.[3] 86.8%. In our study, all the carcinomas were follicular variants of PTC (FVPTC). The study done by Ho et al.[3] showed 48.8% as FVPTCs while the rest were conventional PTCs, whereas the findings of Wong et al.[10] are comparable to our study with FVPTCs accounting for the maximum percentage (81.7%) and conventional being 18.3%.

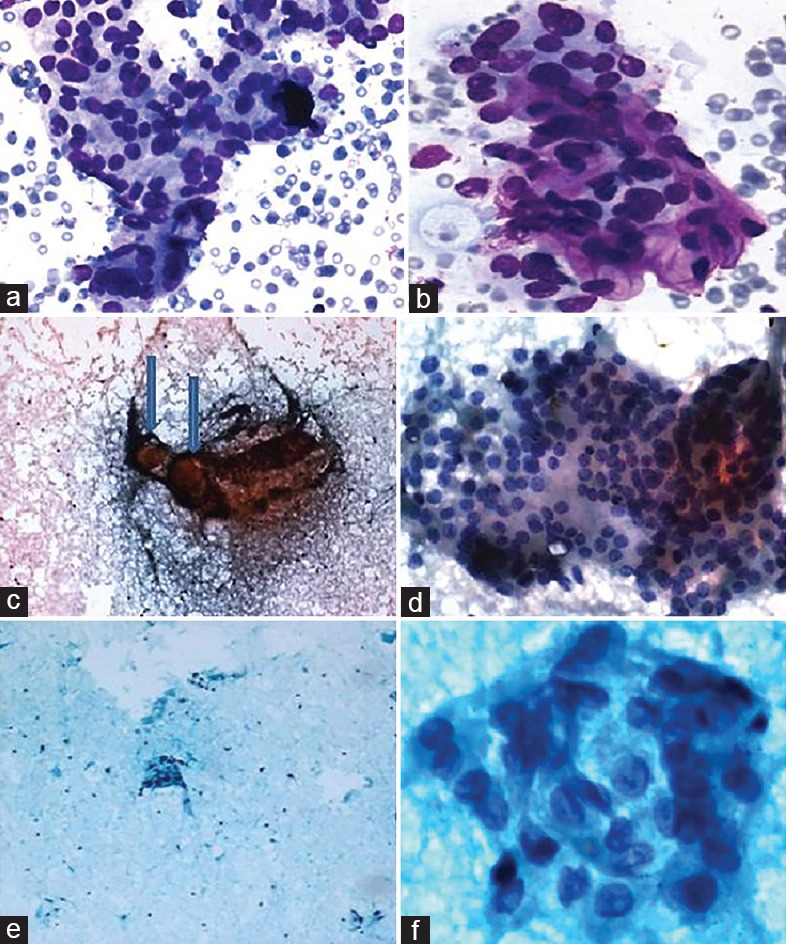

We studied the cytomorphological features of every case of FVPTC that had been classified as category III. It was observed that most of the cases had subtle nuclear features of PTC and significant pallor, frequent grooves or intranuclear cytoplasmic inclusions were not seen. However, nuclear enlargement with crowding and focal nuclear pallor was observed [Figure 1a and b]. Few of them were sparsely cellular and occasional had clotting artefacts [Figure 1c and d], wherein cell morphology was not optimally visualized. Some were benign looking due to abundant thin colloid (e.g., in the macrofollicular variant of PTC), which led to a diagnostic difficulty [Figure 1e and f].

Figure 1.

First case of FVPTC (a) Aspirate showing microfollicular pattern (Giemsa, ×100); (b) subtle nuclear features of PTC (Giemsa, ×400). Second case of FVPTC (c) Aspirate showing clotting artefact, with thick blobs of colloid (arrows) (Pap, ×100), (d) TFC clusters with nuclear enlargement and some pallor (Pap, ×400). Third case of FVPTC (e) Aspirate showing abundant colloid with scant cellularity (Pap × 40); (f) thyroid follicular cell clusters showing focal nuclear features of PTC (Pap, ×400)

Some authors have suggested subclassifiers to further stratify AUS/FLUS cases.[3,10,13,14,15] These studies have shown that even though the overall risk of malignancy is relatively low, subclassifying AUS/FLUS with focal abnormal cytomorphological features may help in better management of patients.

In the present study, a blind review of slides was done retrospectively, in cases where surgical pathology follow up was available (n = 24) and classified in various subcategories in accordance with study done by Ho et al.[3] The main aim was to examine the type of atypia seen in AUS/FLUS category. In a study done by Renshaw et al.,[13] a similar classification was done but they did not include “favor benign category in their study and the rate of malignancy was calculated in each subcategory where surgical follow up was available and it was found that malignancy rate in “Atypia NOS,” “rule out follicular neoplasm.” “rule out Hurthle cell neoplasm,” and “rule out papillary carcinoma” was 27% (4), 22% (16), 7% (3), and 38% (27), respectively. Similarly, in the present study, it was seen that substratification helped detect malignancy better than the broad category III because the risk of malignancy is higher in “AUS/FLUS cannot exclude PTC” category (85.7%) as compared to other categories and the rate of malignancy is zero in “AUS/FLUS favor benign” category [Table 4]. Similar findings were observed in the study done by Ho et al.,[3] however, the subcategories are more sensitive for risk of malignancy in our study as compared to Ho et al.[3] Thus, our findings are in agreement with other studies which suggest that subclassifying AUS/FLUS can impact patient follow up regimens and provide guidance toward a repeat FNA or surgery, especially in multidisciplinary clinical settings.

Table 4.

Malignancy rate in substratified categories

Conclusion

In conclusion, cytologists should strive to better classify “atypical follicular cells” and communicate the true risk of malignancy for each individual patient to help better patient management and care.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Polyzos SA, Kita M, Avramidis A. Thyroid Stepwise diagnosis and management. Hormones. 2007;6:101–19. doi: 10.14310/horm.2002.111107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krane JF, Nayar R, Renshaw AA. Atypia of undetermined significance/Follicular lesion of undetermined significance. In: The Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology Definitions, Criteria and Explanatory notes. 1st ed. Springer: New York; 2010. pp. 37–46. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ho AS, Sarti EE, Jain KS, Wang H, Nixon IJ, Shaha AR, et al. Malignancy rate in thyroid nodules classified as Bethesda Category III (AUS/FLUS) Thyroid. 2014;24:832–9. doi: 10.1089/thy.2013.0317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shi Y, Ding X, Klein M, Surgue C, Matano S, Edelman M, et al. Thyroid fine needle aspiration with atypia of undetermined significance: A necessary or optional category? Cancer. 2009;117:298–304. doi: 10.1002/cncy.20039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cibas ES, Ali S. The Bethesda System for reporting thyroid cytopathology. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009;132:658–65. doi: 10.1309/AJCPPHLWMI3JV4LA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.VanderLaan PA, Marqusee E, Krane JF. Clinical outcome for atypia of undetermined significance in thyroid fine-needle aspirations: Should repeated FNA be the preferred initial approach? Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;135:770–5. doi: 10.1309/AJCP4P2GCCDNHFMY. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chung YS, Yoo C, Jung JH, Choi HJ, Suh YJ. Review of atypical cytology of thyroid nodule according to the Bethesda system and its beneficial effect in the surgical treatment of papillary carcinoma. J Korean Surg Soc. 2011;81:75–84. doi: 10.4174/jkss.2011.81.2.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ratour J, Polivka M, Dahan H, Hamzi L, Kania R, Dumuis ML, et al. Diagnosis of follicular lesions of undetermined significance in fine needle aspirations of thyroid nodules. J Thyroid Res 2013. 2013:250347. doi: 10.1155/2013/250347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Naz S, Hashmi AA, Khurshid A, Faridi N, Edhi MM, Kamal A, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of Bethesda system for reporting thyroid cytopathology: An institutional perspective. Int Arch Med. 2014;7:46. doi: 10.1186/1755-7682-7-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wong LQ, LiVolsi VA, Baloch ZW. Diagnosis of atypia/follicular lesion of undetermined significance: An institutional experience. Cyto J. 2014;11:23. doi: 10.4103/1742-6413.139725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bongiovanni M, Krane JF, Cibas ES, Faquin WC. The atypical thyroid fine-needle aspiration: P, present, and future. Cancer Cytopathol. 2012;120:73–86. doi: 10.1002/cncy.20178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dincer N, Balci S, Yazgan A, Guney G, Ersoy R, Cakir B, et al. Follow-up of atypia and follicular lesions of undetermined significance in thyroid fine needle aspiration cytology. Cytopathology. 2013;24:385–90. doi: 10.1111/cyt.12021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Renshaw AA. Should ―atypical follicular cells‖ thyroid fine needle aspirates be subclassified? Cancer Cytopathol. 2010;118:186–9. doi: 10.1002/cncy.20091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lubitz CC, Faquin WC, Yang J, Mekel M, Gaz RD, Parangi S, et al. Clinical and cytological features predictive of malignancy in thyroid follicular neoplasms. Thyroid. 2010;20:25–31. doi: 10.1089/thy.2009.0208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jing X, Roh MH, Knoepp SM, Zhao L, Michael CW. Minimizing the diagnosis of “follicular lesion of undetermined significance” and identifying predictive features for neoplasia. Diagn Cytopathol. 2011;39:737–42. doi: 10.1002/dc.21459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]