Abstract

Emerging Non-communicable diseases burden move United Nation to call for 25% reduction by 2025 in premature mortality from non-communicable diseases (NCDs). The World Health Organization (WHO) developed global action plan for prevention and control NCDs, but the countries’ contexts, priorities, and health care system might be different. Therefore, WHO expects from countries to meet national commitments to achieve the 25 by 25 goal through adapted targets and action plan.

In this regards, sustainable high-level political statement plays a key role in rules and regulation support, and multi-sectoral collaborations to NCDs’ prevention and control by considering the sustainable development goals and universal health coverage factors.

Therefore, Iran established the national authority’s structure as Iranian Non Communicable Diseases Committee (INCDC) and developed NCDs’ national action plan through multi-sectoral approach and collaboration researchers and policy makers. Translation Iran’s expertise could be benefit to mobilizing leadership in other countries for practical action to save the millions of peoples.

Keywords: Non-communicable diseases, Action plan, Iran

Background

Alarming increase of premature mortality from non-communicable diseases across the world considered by Global action plan on NCDs and Sustainable Development Goals [1–3]. Also, the High-Level Meeting on NCDs in the United Nations emphasized on the need of all government policy response to this dramatic problem [4]. NCDs were responsible to more than 38 million deaths in the world and annually, non-communicable diseases responsible for 16 million premature death [5]. This staggering toll of non-communicable diseases and premature mortality leads policy makers to pay attention and instigate action across the globe [6].

Evidences indicate that, Iran threatened by NCDs too [7–10]. In Iran, during the recent decades, the socio-economic development and the successful function of Primary Health Care (PHC) bring out health promotion, child, and maternal mortality decrease [11]. In addition, life expectancy increased from 66 to 78 years in period of 1990 to 2013.

Following these progresses in health situation of Iranians, a remarkable revolution occurred in the health status of the country especially in the field of communicable diseases. Nevertheless, non-communicable diseases remained as the great health problem in Iran. In 2013, 236 thousand deaths in Iran occurred due to NCDs and there was 14.5% increase of NCDs’ death during two past decades [12]. At the same time, mental disorders, substance abuse and traffic injuries were cause of 15821 deaths. It is remarkable, 82.2% of NCDs’ death is due to cardiovascular diseases, cancers, chronic pulmonary diseases, and diabetes and these are top ranks of cause of death in the country [12]. In Iran, dietary risks are the first line of NCDs’ risk factors and metabolic risk factors stand at second position. Tobacco smoke, air pollution, low physical activity, and alcohol and drug use are the next related risk factors, respectively [12].

In 2013, NCDs led to 7 million years lived with disability (YLD) in Iran [13]. It is considerable, NCDs accompanied with economical burden because of productivity reduction and diverting resources from productive purposes to NCDs treatment. Because of, the poor population struggled with health expenditure and living costs, they have been suffered from economic stress more than other people [12, 14]. It is remarkable; the first cause of catastrophic health expenditures is NCDs and this problem reinforce societal inequities [6, 15].

Non-communicable diseases ignored during the framing of the Millennium Development Goals in 2000, but clarification of the reality leads the policymakers to pay attention to it. The United Nations and the World Health Organization (WHO) have called for a 25% reduction by 2025 in mortality from non-communicable diseases among persons between 30 and 70 years of age, in comparison with mortality in 2010, adopting the slogan “25 by 25” [4].

Universal health coverage (UHC) as a critical component of sustainable development reduces poverty and social inequities through financial risk protection. It is important; the Key elements of the right to health are availability, accessibility, acceptability, quality [16].

By considering these rights and responding to significant burden of NCDs, the World Health Organization (WHO) developed the global action plan for the prevention and control of NCDs (2013–2020) which contain 9 targets by considering four main risk factors; including tobacco use, an unhealthy diet, lack of physical activity and harmful alcohol use. These behavioral risk factors are associated with four main disease clusters mentioned above [17]. As many NCDs’ death and disability are preventable by appropriate interventions, this action plan provides policy options for countries to strengthen them to reduce premature deaths from NCDs by 25% by 2025 [18].

The WHO has messaged; the countries could shift from political commitment to effective action by prioritizing affordable interventions. This organization emphasized on the need of all countries to set national NCDs targets and responsible to attain them [19, 20].

The aim of this paper is to present the emerging Iranian architecture for NCDs’ prevention and control and create NCDs’ national action plan to move forward.

Response to emerging NCDs’ epidemic

Political commitment

Mandate with the task of developing a national action plan for NCDs’ prevention and control was the opportunity for Iran to commitment 25 by 25 NCDs goal [21]. In context of national action plans, we could arrange feasible, scalable, affordable, and cost effective interventions to reduce NCDs’ mortality and morbidity and attain to the most efficient and equitable health system [22, 23].

Success in response to NCDs crisis depends on strong and effective leadership in high-level political statement [24]. In this way, health policies support regulatory, legislative and inter-sectoral collaborations to address equity and reduction NCDs’ outcomes.

Establishment sustainable national leadership

Ministry of Health and Medical Education (MOHME) of Iran as strong and effective leadership in high-level political statement established Iranian non-communicable diseases committee (INCDC) with the aim of comprehensive policy making, planning, and monitoring of all activities in the area of non-communicable diseases in Iran.

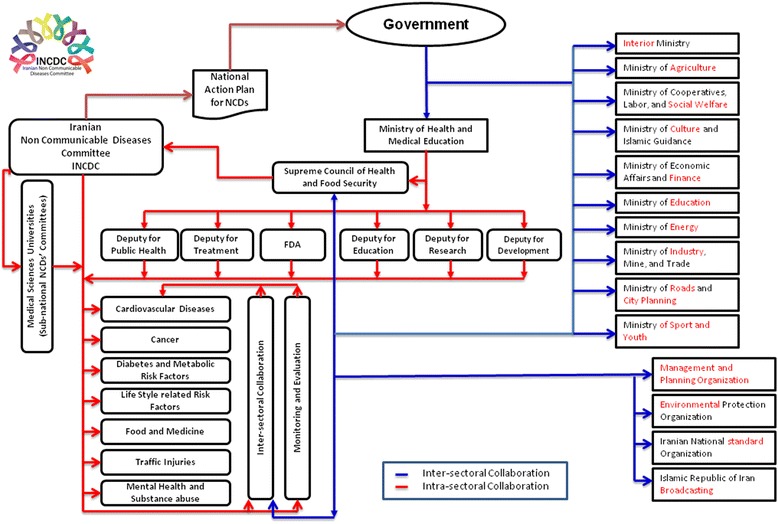

As shown in Fig. 1, INCDC set up by inter and intra-sectoral collaboration. The presented flow demonstrates the relationships between inter and intra-sectoral parts. The body of INCDC contains ministry of health deputies, supreme council of health and food security and related to medical sciences universities.

Fig. 1.

The inter and intra- sectoral collaboration of Iranian Non Communicable Diseases Committee

Iranian non-communicable diseases committee has nine sub-committees according to various aspects of prevention and controls NCDs and their risk factors and national targets (Fig. 1).

A stepwise move toward action

First step: setting clear and appropriate targets in national level

Planning is one of the key steps for responding to NCDs’ dramatic epidemic [25]. “National Action Plan for Prevention and Control of Non-Communicable Diseases and the related risk factors in Iran, 2015-2025” was developed by considering our country’s priorities, National and Sub-national Burden of Diseases, and WHO global targets [1, 26–29].

The national action plan for NCDs Prevention and Control in Iran including 9 targets based on global action plan for NCDs and 4 special targets regarding trans fatty acid, traffic injuries, drug abuse, and mental diseases.

Among nine global targets on prevention and control NCDs, target 3 and target 8 adapted for our country situation. According to WHO report, Prevalence of insufficient physical activity in Iranian adult was 24.1% among men and 42.9% among women [30, 31]. The 3th target of NCDs global action plan set to reduce physical inactivity by 10% by 2025. According to our country situation, we considered 20% reduction of physical inactivity.

In addition, the eighth target of global action plan set to receiving drug therapy and counseling to prevent heart attacks and strokes by 50% of eligible people. But we accelerate this desired measure to 70% because of access to medicines plays a vital role in universal health coverage goals achievement and already we stand up good point [32]. It is remarkable, the other targets were appropriate for Iran by considering our conditions and situation analysis.

In addition to glossary WHO targets, United Nation proposed Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The third sustainable development goal focused on health and considered UHC as a mean of health equity. It is needed to effective attention to non-communicable diseases [33].

By considering burden of diseases in Iran, targets 10 to 13 set for our country (Table 1).

Table 1.

Iranian National Action Plan Targets on NCDs and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

| Iranian National Action Plan Targets on NCDs | Sustainable Development Goals | Universal Health Coverage Goals | Health System Goals |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target 1.25% relative reduction in the risk of premature death from cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes, chronic respiratory diseases | SDGs Target 3.4.By 2030, reduce by one third premature mortality from non-communicable diseases through prevention and treatment and promote mental health and well-being | Utilization Quality Financial protection |

Responsiveness Health gain and equity in health Financial protection and equitable finance |

| Target 2. At least 10% relative reduction in alcohol consumption | SDGs Target 3.5. Strengthen the prevention and treatment of substance abuse, including narcotic drug abuse and harmful use of alcohol | ||

| Target 3. A 20% relative reduction in prevalence of insufficient physical activity | SDGs Target 3.d.Strengthen the capacity of all countries, in particular developing countries, for early warning, risk reduction and management of national and global health risks | ||

| Target 4.30% relative reduction in the average salt intake in the population | SDGs Target 3.d. Strengthen the capacity of all countries, in particular developing countries, for early warning, risk reduction and management of national and global health risks | ||

| Target 5.30% relative reduction in the prevalence of tobacco use in persons aged 15+ years | SDGs Target 3a. Strengthen the implementation of the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control in all countries, as appropriate | ||

| SDGs Target 3.d. Strengthen the capacity of all countries, in particular developing countries, for early warning, risk reduction and management of national and global health risks | |||

| Target 6.25% relative reduction in the prevalence of high blood pressure or contain the prevalence of raised blood pressure | SDGs Target 3.d. Strengthen the capacity of all countries, in particular developing countries, for early warning, risk reduction and management of national and global health risks | ||

| Target 7. Halt the rates of diabetes and obesity | SDGs Target 3.d. Strengthen the capacity of all countries, in particular developing countries, for early warning, risk reduction and management of national and global health risks | ||

| Target 8. At least 70% of eligible people receive drug therapy and counseling to prevent heart attacks and strokes | SDGs Target 3.8. Achieve universal health coverage, including financial risk protection, access to quality essential health-care services and access to safe, effective, quality and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all | ||

| Target 9. An 80% availability of the affordable basic technologies and essential medicines, including generics in private and public sectors | SDGs Target 3.8. Achieve universal health coverage, including financial risk protection, access to quality essential health-care services and access to safe, effective, quality and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all | ||

| SDGs Target 3b. Support the research and development of vaccines and medicines for the communicable and non-communicable diseases that primarily affect developing countries, provide access to affordable essential medicines and vaccines, in accordance with the Doha Declaration on the TRIPS Agreement and Public Health, which affirms the right of developing countries to use to the full the provisions in the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights regarding flexibilities to protect public health, and, in particular, provide access to medicines for all | |||

| SDGs Target 3.c. Substantially increase health financing and the recruitment, development, training and retention of the health workforce in developing countries, especially in least developed countries and small island developing States | |||

| Target 10. Zero Trans fatty acid in food & oily products | SDGs Target 3.d. Strengthen the capacity of all countries, in particular developing countries, for early warning, risk reduction and management of national and global health risks | ||

| Target 11.20% Relative reduction in mortality rate due to traffic injuries | SDGs Target 3.6.By 2020, halve the number of global deaths and injuries from road traffic accidents | ||

| Target 12. A 10% relative reduction in mortality rate due to drug abuse | SDGs Target 3.5. Strengthen the prevention and treatment of substance abuse, including narcotic drug abuse and harmful use of alcohol | ||

| Target 13.20% increase in access to treatment for mental diseases | SDGs Target 3.4.By 2030, reduce by one third premature mortality from non-communicable diseases through prevention and treatment and promote mental health and well-being |

In Table 1, 13 national targets of Iran and their relationship with Sustainable Development Goals presented [2, 34–36]. UHC and health system goals are related to all NCDs targets and all of them are in the way of poverty reduction.

Second step: mobilization, inter & intra-sectoral collaboration and developing national action plan for NCDs prevention and control in Iran

In developing NCDs’ national action plan of Iran, inter and intra-sectoral collaboration was considered. INCDC initiated dialogue with health system sectors and the other ministries to response NCDs’ prevention and control. This multi-sectoral procedure and collaborating approach led to develop the national document based on recommended WHO framework contain four areas of governance, prevention and reduction of risk factors, health care, and surveillance, monitoring and evaluation.

Through collaborative planning, the time bounded national action plan was prepared based on clear policies with clarified targets, strategies and activities and determined stakeholders, desired outcome, evaluation criteria, and resources [34].

Third step: enlist the support of national and international policy makers

Prepared NCDs’ action plan supported by President, parliament speaker, Vice President, Head of Management and Planning Organization, Head of Environmental Protection Organization, Head of Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting, and nine Ministers in the government Cabinet. This holistic political support and responsibility might be unique in the region. It is remarkable, supreme council of health, chaired by president approved “National Action Plan for Non-Communicable Diseases Prevention and Control in Iran” and minister of health directed medical sciences universities to implement it in order to health promotion of community as the main stakeholder through sub-national NCDs’ committee.

Forth step: participation of sub-national policy makers

Iran has 61 Medical Sciences University which their health services covered all provinces of Iran. Integration of medical education and health in the Ministry of Health and Medical Education create appropriate atmosphere for strengthening the health care system in Iran [37, 38]. Towards realizing NCDs’ prevention and control targets, INCDC invited Medical Sciences Universities’ chancellors as the main authorities in sub-national health sectors. They could be directed provincial committees through collaborative arrangements to address local priorities and should be committed to multi-sectoral approach. This approach is essential among planning, implementation and accountability as key stages of response to NCDs’ problem [25].

To accelerate country response to non-communicable diseases prevention and control, policy makers could follow these strategies to strengthen governance, risk reduction, health care, and surveillance. Generating national and sub-national information and monitor the trends of NCDs and their risk factors, establishing health promotion programs across the life course through primary health care system and universal health coverage components, and tackling issues through multi-sectoral approach are critical strategies be suggested.

Conclusion

The structured and stepwise approach of Iran towards NCDs prevention and control bring out a proposed way in the mixture of challenges and successes. Our experiences indicate that the Strong leadership needed to pass the way of fighting against NCDs. We emphasized on this principle; the successful response to NCDs need to multi-sectoral approach, the engagement of all health sectors and related stakeholders including other ministries and organizations [34].

Iranian Non-communicable Diseases Committee (INCDC) is an appropriate model in supreme level for mega coordination [39, 40]. According to NCDs’ progress monitor report of WHO, Iran stand up the first rank in Eastern Mediterranean region and could be share lesson learned to other countries [41].

Resource mobilization, technical allocation, health workforce development and health care quality improvement are essential for action plan implementation. Poor leadership, change management, financial constraints, poor health infrastructure, inadequate qualified human resources, poor information and communication, poor coordination and resistance of some organizations might be lead to implementation collapse [42, 43]. But, clear vision and mission, stability of political factors, local authorities support, financial resources management, motivating private sector and emerging economic powers, Internal monitoring and evaluation, strengthening supportive supervision and increasing motivation through recognition of best practice could be benefit for successful implementation.

Overcoming possible barriers in action plan implementations, scaling up interventions and health management in various levels of health services leads to reduce years of life lost (YLL) and YLD due to NCDs and finally benefit for health equity and financial protection [44].

President, parliament, supreme council of health members and cabinet ministers’ support and collaboration with other ministries and organizations were unique experience in the region. Access to efficient epidemiological information, explicit views of national policy makers in various domains of public health, treatment, food and medicine, education, and research. Partnership of policy and decision makers, scientist, researchers and health experts in national action plan development, establishment national sub committees guided by national authorities and structuring the provincial committees as the frontline of health services were our strengths.

Of course, we faced to some challenges in resource mobilization. Despite our long-term goals, INCDC was not finance by specific and sufficient budget. In addition, lack of private health sector and Nongovernmental organizations’ collaboration was the other limitation could be considered in the way forward. The other important challenge was incompleteness and misclassification reporting of cause of death that addressed by National and Sub-national Burden of Diseases Study (NASBOD) and now, we have comprehensive atlas of death in by cause in various levels [26].

Finally, Similar to other experience, we suggest integration of NCDs’ prevention and control in primary health care, enforce appropriate interventions led by provincial committee, technical use of existing infrastructure and human resources, innovative resource mobilization such as funding through nongovernmental resource, provide progress monitoring system and ensure accountability from the involved sectors, and actions to accelerate progress [20, 36, 45].

Acknowledgements

We acknowledged all health system’s experts and researchers contributed in this national commitment. This was not possible without fruitful effort of them.

Funding

Ministry of Health and Medical Education covered all financial resources of this policy action.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during current study.

Authors’ contributions

NP writing the article, HH, RD, MHA, RM, AS, AAS, MA, AD, FF, AH, RH, HJ, NK, AK, AT coordinating process of this national policy action, BL, FF, and RH commented on manuscript, BL managed all phases of this process. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- INCDC

Iranian Non Communicable Diseases Committee

- MOHME

Ministry of Health and Medical Education

- NASBOD

National and Sub-national Burden of Diseases Study

- NCDs

Non-communicable diseases

- PHC

Primary health care

- SDGs

Sustainable development goals

- UHC

Universal health coverage

- WHO

World Health Organization

- YLD

Years lived with disability

- YLL

Years of life lost

Contributor Information

Niloofar Peykari, Email: n.peykari@behdasht.gov.ir.

Hassan Hashemi, Email: hhashemi@sina.tums.ac.ir.

Rasoul Dinarvand, Email: dinarvand@fda.gov.ir.

Mohammad Haji-Aghajani, Email: dr.aghajani@yahoo.com.

Reza Malekzadeh, Email: dr.reza.malekzadeh@gmail.com.

Ali Sadrolsadat, Email: a.sadr@behdasht.gov.ir.

Ali Akbar Sayyari, Email: drsayyari@hotmail.com.

Mohsen Asadi-lari, Email: mohsen.asadi@yahoo.com.

Alireza Delavari, Email: delavariar@yahoo.com.

Farshad Farzadfar, Email: Farzadfar3@yahoo.com.

Aliakbar Haghdoost, Email: ahaghdoost@gmail.com.

Ramin Heshmat, Email: rheshmat@tums.ac.ir.

Hamidreza Jamshidi, Email: jamshidik@gmail.com.

Naser Kalantari, Email: nkalantari1334@gmail.com.

Ahmad Koosha, Email: amkousha@hotmail.com.

Amirhossein Takian, Email: takiana@gmail.com.

Bagher Larijani, Phone: +98 21 88363560-80, Email: larijanib1340@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Global action plan for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases 2013–2020. Geneva, World Health Organization; 2013. Available from: who.int/nmh/events/ncd_action_plan/en/. [Cited 2016 Sep 19].

- 2.Sustainable Development Goals. New York, The United Nations; Available from: The: http://www.sustainabledevelopment.un.org/?menu=1300. [Cited 2016 Oct 2].

- 3.Alwan A. The world health assembly responds to the global challenge of noncommunicable diseases. East Mediterr Health J. 2013;19(6):511–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.UN General Assembly. Political declaration of the high-level meeting of the general assembly on the prevention and control of non-communicable diseases. A/66/L.1. New York, The United Nations; 2011. Available from: http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/66/L.1. [Cited 2016 Oct 2].

- 5.Global status report on NCDs 2014. Geneva, World Health Organization; 2014. www.who.int/nmh/publications/ncd-status-report-2014/en/. [Cited 2016 Oct 2].

- 6.David J, Hunter KSR. Noncommunicable diseases. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1336–1343. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1109345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haagsma JA, Graetz N, Bolliger I, Naghavi M, Higashi H, Mullany EC, et al. The global burden of injury: incidence, mortality, disability-adjusted life years and time trends from the global burden of disease study 2013. Inj Prev. 2016;22(1):3–18. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2015-041616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Non-communicable Diseases (NCD) Country Profiles. Geneva, World Health Organization; 2014. Available from: http://who.int/nmh/countries/irn_en.pdf?ua=1. [Cited 2016 Sep 3].

- 9.NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC) Trends in adult body-mass index in 200 countries from 1975 to 2014: a pooled analysis of 1698 population-based measurement studies with 19.2 million participants. Lancet. 2016;387(10026):1377–1396. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30054-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC) Worldwide trends in diabetes since 1980: a pooled analysis of 751 population-based studies with 4.4 million participants. Lancet. 2016;387(10027):1513–1530. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00618-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Asadi-Lari M, Sayyari A, Akbari M, Gray D. Public health improvement in Iran—lessons from the last 20 years. Public Health. 2004;118(6):395–402. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2004.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Global burden of Diseases. Washington, Institute of Health Metric and Evaluation; 2014, Available from: http://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/. [Cited 2016 Sep 3].

- 13.Vos T, Barber RM, Bell B, Bertozzi-Villa A, Biryukov S, Bolliger I, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet. 2015;386(9995):743–800. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60692-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richards NC, Gouda HN, Durham J, Rampatige R, Rodney A, Whittaker M. Disability, noncommunicable disease and health information. Bull World Health Organ. 2016;94(3):230–232. doi: 10.2471/BLT.15.156869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peykari N, Djalalinia S, Qorbani M, Sobhani S, Farzadfar F, Larijani B. Socioeconomic inequalities and diabetes: a systematic review from Iran. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2015;14:8. doi: 10.1186/s40200-015-0135-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferguson L, Tarantola D, Hoffmann M, Gruskin S. Non-communicable diseases and human rights: Global synergies, gaps and opportunities. Global Public Health. 2016;1–28. Available at: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/17441692.2016.1158847. [ Cited in 25 Dec 2016]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Low WY, Lee YK, Samy AL. Non-communicable diseases in the Asia-Pacific region: prevalence, risk factors and community-based prevention. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2015;28(1):20–26. doi: 10.2478/s13382-014-0326-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sanghera D. Emerging epidemic of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) in south Asia: opportunities for prevention. J Diab Metab. 2016;7(647):2. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mendis S, Davis S, Norrving B. Organizational update: the world health organization global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2014; one more landmark step in the combat against stroke and vascular disease. Stroke. 2015;46(5):e121–e122. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.008097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bowman S, Unwin N, Critchley J, Capewell S, Husseini A, Maziak W, et al. Use of evidence to support healthy public policy: a policy effectiveness-feasibility loop. Bull World Health Organ. 2012;90(11):847–853. doi: 10.2471/BLT.12.104968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rajabi F, Esmailzadeh H, Rostamigooran N, Majdzadeh R. What must be the pillars of Iran’s health system in 2025? values and principles of health system reform plan. Iran J Public Health. 2013;42(2):197. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scaling up action against non-communicable diseases:how much will it cost? Geneva: World Health Organization, 2011; Available from: www.who.int/nmh/publications/cost_of_inaction/en/. [Cited 2016 Sep 25].

- 23.Moghaddam AV, Damari B, Alikhani S, Salarianzedeh M, Rostamigooran N, Delavari A, et al. Health in the 5th 5-years development plan of Iran: main challenges, general policies and strategies. Iran J Public Health. 2013;42(Supple1):42–49. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beaglehole R, Bonita R, Alleyne G, Horton R, Li L, Lincoln P, et al. UN high-level meeting on non-communicable diseases: addressing four questions. Lancet. 2011;378(9789):449–455. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60879-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bonita R, Magnusson R, Bovet P, Zhao D, Malta DC, Geneau R, et al. Country actions to meet UN commitments on non-communicable diseases: a stepwise approach. Lancet. 2013;381(9866):575–584. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61993-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Farzadfar F, Delavari A, Malekzadeh R, Mesdaghinia A, Jamshidi HR, Sayyari A, et al. NASBOD 2013: design, definitions, and metrics. Arch Iran Med. 2014;17(1):7–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ghasemian A, Ataie-Jafari A, Khatibzadeh S, Mirarefin M, Jafari L, Nejatinamini S, et al. National and sub-national burden of chronic diseases attributable to lifestyle risk factors in Iran 1990–2013; study protocol. Arch Iran Med. 2014;17(3):146–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peykari N, Sepanlou SG, Djalalinia S, Kasaeian A, Parsaeian M, Ahmadvand A, et al. National and sub-national prevalence, trend, and burden of metabolic risk factors (MRFs) in Iran: 1990–2013, study protocol. Arch Iran Med. 2014;17(1):54–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peykari N, Saeedi MS, Djalalinia S, Kasaeian A, Sheidaei A, Mansouri A, et al. High fasting plasma glucose mortality effect: a comparative risk assessment in 25–64 years old Iranian population. Int J Prev Med. 2016;7:75. doi: 10.4103/2008-7802.182732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prevalence of insufficient phisycal activity. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. Available from: http://gamapserver.who.int/gho/interactive_charts/ncd/risk_factors/physical_inactivity/atlas.html?indicator=i1&date=Female. [Cited 2016 Sep 25].

- 31.Prevalence of insufficient phisycal activity. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. Available from:http://gamapserver.who.int/gho/interactive_charts/ncd/risk_factors/physical_inactivity/atlas.html?indicator=i1&date=Male. [Cited 2016 Sep 25].

- 32.Beran D, Perrin C, Billo N, Yudkin JS. Improving global access to medicines for non-communicable diseases. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2(10):e561–e562. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70189-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmidt H, Gostin LO, Emanuel EJ. Public health, universal health coverage, and sustainable development goals: can they coexist? Lancet. 2015;386(9996):928–930. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60244-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hashemi H, Larijani B, Sayari AK, Malekzadeh R, Dinarvand R, Aghajani M, et al. Iranian Non Communicable Diseases Committee (INCDC), Ministry of Heath and Medical Education. National Action Plan for Prevention and Control of NCDs and the Related Risk Factors in the Islamic Republic of Iran, 2015 to 2025. Tehran, Iran; 2015. Available from: http://incdc.behdasht.gov.ir/uploads/sanadmelli_en.pdf. [cited 2016 May 8].

- 35.Kutzin J. Health financing for universal coverage and health system performance: concepts and implications for policy. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91(8):602–611. doi: 10.2471/BLT.12.113985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Magnusson RS, Patterson D. The role of law and governance reform in the global response to non-communicable diseases. Global Health. 2014;10:44. doi: 10.1186/1744-8603-10-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mehrdad R. Health system in Iran. JMAJ. 2009;52(1):69–73. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marandi SA. The integration of medical education and health care system in the Islamic Republic of Iran: a historical overview. J Med Educ. 2001;1(1):8–10. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hashemi H, Larijani B, Sayari AK, Malekzadeh R, Dinarvand R, Aghajani M, et al. Report on prevention and control of non communicable diseases to celebrate the first anniversary of INCDC establishment. Tehran: Iranian Non-communicable Diseases Committee, Ministry of Heath and Medical Education; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mendis S, Chestnov O. Policy reform to realize the commitments of the political declaration on noncommunicable diseases. Br Med Bull. 2013;105:7–27. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldt001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Noncommunicable Diseases Progress Monitor 2015. Geneva: World Health Organization; Available from: 2015. http://www.who.int/nmh/media/ncd-progress-monitor/en/. [Cited 2016 Oct 2].

- 42.Aldehayyat JS, Anchor JR. Strategic planning implementation and creation of value in the firm. Strateg Chang. 2010;19(3–4):163–176. doi: 10.1002/jsc.866. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bolo AZ, Nkirote KC. Bottleneck in the execution of Kenya vision 2030 strategy: an empirical study. PJ Bus Adm Manag. 2012;2(3):505–512. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maher D, Harries AD, Zachariah R, Enarson D. A global framework for action to improve the primary care response to chronic non-communicable diseases: a solution to a neglected problem. BMC Public Health. 2009;9(1):355. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lupafya PC, Mwagomba BL, Hosig K, Maseko LM, Chimbali H. Implementation of policies and strategies for control of noncommunicable diseases in Malawi: challenges and opportunities. Health Educ Behav. 2016;43(1 Suppl):64S–69S. doi: 10.1177/1090198115614313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during current study.