Abstract

Background

To identify molecular alterations in skeletal muscle in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) that may contribute to ongoing disability in RA.

Methods

Persons with seropositive or erosive RA (n = 51) and control subjects matched for age, gender, race, body mass index (BMI), and physical activity (n = 51) underwent assessment of disease activity, disability, pain, physical activity and thigh muscle biopsies. Muscle tissue was used for measurement of pro-inflammatory markers, transcriptomics, and comprehensive profiling of metabolic intermediates. Groups were compared using mixed models. Bivariate associations were assessed with Spearman correlation.

Results

Compared to controls, patients with RA had 75% greater muscle concentrations of IL-6 protein (p = 0.006). In patients with RA, muscle concentrations of inflammatory markers were positively associated (p < 0.05 for all) with disease activity (IL-1β, IL-8), disability (IL-1β, IL-6), pain (IL-1β, TNF-α, toll-like receptor (TLR)-4), and physical inactivity (IL-1β, IL-6). Muscle cytokines were not related to corresponding systemic cytokines. Prominent among the gene sets differentially expressed in muscles in RA versus controls were those involved in skeletal muscle repair processes and glycolytic metabolism. Metabolic profiling revealed 46% higher concentrations of pyruvate in muscle in RA (p < 0.05), and strong positive correlation between levels of amino acids involved in fibrosis (arginine, ornithine, proline, and glycine) and disability (p < 0.05).

Conclusion

RA is accompanied by broad-ranging molecular alterations in skeletal muscle. Analysis of inflammatory markers, gene expression, and metabolic intermediates linked disease-related disruptions in muscle inflammatory signaling, remodeling, and metabolic programming to physical inactivity and disability. Thus, skeletal muscle dysfunction might contribute to a viscous cycle of RA disease activity, physical inactivity, and disability.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s13075-016-1215-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Gene expression, Metabolomics, Satellite cells, Fibrosis, Inflammation

Background

Despite a vast array of pharmacologic agents available to treat rheumatoid arthritis (RA), management is often complicated by insufficient treatment response, drug toxicity and contraindications, poor access to care and/or medications, and/or damage that predates medical intervention. These barriers lead to or are accompanied by systemic manifestations, disease-associated co-morbidities, chronic pain, physical inactivity, dysmobility, and poor physical function. Thus, further advances in RA care require identification of factors contributing to persistent deficiencies in quality of life and physical function, despite access to excellent anti-rheumatic medications.

Importantly, inactivity and muscle wasting are two important contributors to RA-related morbidity and mortality. Approximately half of patients with RA do not perform even a single bout of weekly physical exercise [1]. The sedentary lifestyle common to patients with RA gives rise to physical deconditioning and muscle atrophy, both of which are associated with osteoporosis, impaired immune function, glucose intolerance, insulin resistance, loss of independence, and increased mortality [2].

In addition to physical inactivity, other factors that likewise promote muscle loss and disability in patients with RA include inadequate protein ingestion, glucocorticoid treatment, and pro-inflammatory cytokines, all resulting in reduced myocyte protein synthesis and increased protein degradation [2, 3]. Inflammation can impact normal muscle turnover and responses to injury, both of which require an exquisitely coordinated remodeling process involving activation, proliferation and differentiation of muscle stem cells—also known as satellite cells. These processes are mediated largely by signals from intramuscular immune cells: neutrophils, regulatory T cells, pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages, and anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages.

The established roles of inflammation in both skeletal muscle remodeling and RA pathophysiology raise obvious questions regarding the potential interplay between muscle dysfunction and RA morbidity. Whereas the link between pro-inflammatory cytokines and muscle dysfunction has been investigated intensely in the context of diseases such as diabetes and cancer cachexia, this topic has remained surprisingly unexplored in RA. In the current study we sought to identify molecular perturbations in muscle specimens from individuals with RA, and to test the hypothesis that skeletal muscle inflammatory markers and derangements in tissue remodeling might contribute to metabolic decline and disability in these patients. Herein, we report that disease-activity-related muscle inflammatory markers are related to physical inactivity, and moreover, that disrupted skeletal muscle repair processes are associated with greater disability. These findings support a model in which skeletal muscle deterioration contributes to a vicious cycle of disease activity, muscle inflammatory signaling and disrupted remodeling, physical inactivity, and disability in patients with RA.

Methods

Design and participants

This was a cross-sectional investigation of individuals with RA and matched controls collected from the Durham, NC area. The RA group met the following criteria: (1) RA diagnosis meeting American College of Rheumatology 1987 criteria [4]; (2) seropositive disease (positive rheumatoid factor or anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide) or evidence of erosions on hand or foot imaging; (3) no medication changes within the three months prior to study enrollment; and (4) daily prednisone use ≤5 mg. Healthy participants without a diagnosis of RA, without joint pain, and without joint swelling lasting more than a week were matched to individual participants with RA by gender, race, age within 3 years, and body mass index (BMI) within 3 kg/m2. Exclusions included current pregnancy, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and known coronary artery disease. Further specific details on questionnaires and measurement protocols have previously been described [5]. This study was in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration and was approved by the Duke University Institutional Review Board.

Assessments of both groups included questionnaires, physical exams for disease status, fasting blood collection, intravenous glucose tolerance tests for insulin sensitivity, 7 days of accelerometer-measured physical activity, computed tomography (CT) imaging of abdomen and thigh, and vastus lateralis muscle biopsies [5]. Disability (health assessment questionnaire-disability index (HAQ-DI) and co-morbidities (co-morbidity index) were assessed by previously published questionnaires [6, 7]. Disease activity assessed by the disease activity score in 28 joints (DAS-28) was determined from a patient-completed visual analog scale, physician-determined numbers of tender and swollen joints, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate [8]. Plasma concentrations of inflammatory markers and cytokines were determined by immunoassay [5] and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy (GlycA) [9]. Insulin sensitivity was determined using Bergman’s minimal model [10] and concentrations of glucose and insulin (glucose: Beckman-CoulterDXC600; insulin: electrochemiluminscent assay from Meso Scale Discovery) at each of 29 time points during the intravenous glucose tolerance test.

Physical activity was measured with 7 days of accelerometry. After completing assessments, accelerometers (RT3, Stayhealthy, Inc., Monrovia, CA, USA) were provided to participants. Participants also received a pre-addressed and postage-applied box for return and directions for wearing on the waist above the right knee during waking hours for 7 days. Accelerometer data were evaluated for validity and non-wear time, and categorized into metabolic equivalents (METs) as previously described [11]. After data cleaning, valid data were available for 41 persons with RA and 31 controls. Time spent exercising was defined as the sum of time spent performing activity at METs equal to or greater than 3. CT scan analyses were performed using OsiriX (Pixmeo) to determine adipose and muscle tissue size and muscle tissue density (greater tissue density is indicative of less inter-muscular adipose tissue) [5]. Standard Bergstrom needle muscle biopsies were performed on the vastus lateralis in the fasting state; participants consumed only water during the 12 hours overnight prior to the biopsy [12]. Tissue was flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 ° C.

Skeletal muscle inflammatory marker measurements

Flash frozen muscle samples (5–10 mg) were homogenized in a buffer consisting of 1% Nonidet-P40, 1 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, and 20 mM Tris-Cl for ELISA-based measures of muscle (m) interleukin (IL)-1β, mIL-6, mIL-8, m-tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α (MSD 4-plex; K15053D-1) and m-toll like receptor (TLR)-4 (Abnova; KA1238). Assays were performed according to the manufacturers’ directions except for the addition of a 30-minute, room temperature, blocking step with 5% BSA followed by three PBS-T washes. Concentrations were normalized to starting masses. Spike-and-recovery assays for all analytes achieved 80–100% recovery confirming lack of assay interference by muscle homogenates. For each cytokine, the mean intra-assay and inter-assay coefficients of variation were: mIL-1β 8.5%, 13.2%; mIL-6 3.5%, 1.5%; mIL-8 4.0%, 4.0%; mTNF-α 8.4%, 10.4%; and mTLR-4 1.7% (only one plate was used for analyses).

Gene expression analyses

Muscle samples were selected for gene expression analyses in an effort to span the range of RA disease activity seen in the larger sample; these corresponded to the following DAS-28 categories: remission (n = 7), low (n = 4), moderate (n = 6), and high activity (n = 3). For each RA muscle sample, the corresponding sample from a control matched by age, gender, and BMI was included.

For RNA preparation, flash frozen muscle samples (20–30 mg) were homogenized in 1 mL TRIzol® (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc, Waltham, MA, USA). Biotinylated total RNA was generated using the Illumina TotalPrep RNA amplification kit (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA); 200 nanograms of RNA were used for the kit. The quality of the RNA was determined using the Bioanalyzer RNA Nano chip assay (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Quantification of the RNA was determined using the Quant-iT RiboGreen RNA Assay Kit. The Human HT-12v3 Expression BeadChip (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) was used for quantitative whole genome RNA profiling. Biotinylated RNA (750 ng) was hybridized to the BeadChip and washed; Cy3-SA was then introduced to the hybridized samples and the BeadChips scanned on the Illumina iScan system according to manufacturer’s protocol. Quality control was performed using the Illumina GenomeStudio tools.

Gene expression fold-differences between groups were compared in Partek Genomics Suite (Partek, Inc.; St. Louis, MO, USA). For pathway analyses, differentially expressed genes (p < 0.02) were evaluated using the Ingenuity Pathway Analysis software (IPA, www.ingenuity.com). IPA identified the canonical pathways containing the greatest number of significant, differentially expressed genes in the dataset. IPA also generated novel networks of related genes and molecules based on the relationships present in the current literature.

Skeletal muscle metabolic intermediate measurements

Metabolites were measured in muscle from all participants (n = 102). Flash frozen muscle biopsies weighing approximately 25 mg were diluted 20 times (wt:vol) in ice-cold 50% acetonitrile containing 0.3% formate and homogenized for 120 sec in a TissueLyser II (Qiagen) at 30 Hz. Amino acids, organic acids, and acylcarnitines were analyzed using stable isotope dilution techniques in the Duke Molecular Physiology Metabolomics Core. Amino acids and acylcarnitine measurements were made by flow injection tandem mass spectrometry (MS) as previously described [13, 14]. The data were acquired using a Micromass Quattro Micro liquid chromatography (LC)-MS system running MassLynx 4.0 software (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, USA). Organic acids were quantified using methods described previously [15] employing Trace Ultra GC coupled to ISQ MS operating under Xcalibur 2.2 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Austin, TX, USA). All data are expressed as picomoles/mg tissue.

Statistical analyses

Accounting for the repeated measures in matched participants, patients with RA and controls were compared using mixed models. Muscle inflammatory molecules and metabolic intermediates were logarithmically transformed prior to group comparisons. Bivariate associations were assessed with Spearman correlation. Gene expression fold-changes were compared in Partek using analysis of variance (ANOVA). All other statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS, Cary, NC). All data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Results

Clinical measures and skeletal muscle inflammatory markers

As shown in Table 1, persons with RA were well-matched to controls by age, gender, and BMI. Patients with RA were recruited based on the inclusion criteria described and without respect to physical activity levels, body mass or body composition; similarly controls were included upon matching a patient with RA by age, gender, and BMI. Despite this, patients with RA and controls were similar with respect to physical activity levels, abdominal and thigh adipose depot size, muscle area, and muscle density [5, 11]. In those with RA, there was more co-morbidity, disability, and systemic inflammation; specifically, greater serum concentrations of high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), IL-6, and TNF-α (p < 0.05 for all) [5]. When skeletal muscle inflammatory markers were compared, there was approximately two times greater concentrations of the muscle cytokines, mIL-6 (p = 0.006) and mIL-8 in RA (p = 0.059) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| Variable | All participants (n = 102) | Rheumatoid arthritis (n = 51) | Matched controls (n = 51) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 54.2 (12.5) | 54.8 (13.2) | 53.8 (11.9) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 30.0 (6.4) | 30.3 (7.5) | 29.6 (5.1) |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 94.1 (15.2) | 94.9 (16.8) | 92.9 (13.3) |

| Race | |||

| Caucasian | 74 (72.6%) | 36 (70.6%) | 38 (74.5%) |

| African American | 27 (26.5%) | 14 (27.5%) | 13 (25.5%) |

| Pacific Islander | 1 (1.0%) | 1 (2.0%) | 0 |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 72 (70.6%) | 36 (70.6%) | 36 (70.6%) |

| Male | 30 (29.4%) | 15 (29.4%) | 15 (29.4%) |

| Physical activity (kCal/day) | 557.1 (280.8) | 517.7 (279.4) | 609.1 (278.7) |

| Physical activity (MET-hr/day) | 5.4 (2.6) | 4.9 (2.5) | 6.0 (2.5) |

| Disease duration (months) | NA | 138.9 (136.3) | NA |

| HAQ-disability index | 0.46 (0.6) | 0.68 (0.7)* | 0.00 (0.0) |

| Comorbidity index | 1.2 (1.2) | 1.6 (1.1)* | 0.6 (0.9) |

| DAS-28 mean (SD) | NA | 3.0 (1.4) | NA |

| Remission (DAS-28 < 2.6) | 19 (40%) | ||

| Low activity (DAS-28 2.6‒3.2) | 8 (17%) | ||

| Moderate activity (DAS-28 3.2‒5.1) | 16 (33%) | ||

| High activity (DAS-28 > 5.1) | 5 (10%) | ||

| Rheumatoid factor positive | NA | 42/47 (89.4%) | NA |

| Anti-cyclic citrullinated antibody positive | NA | 21/22 (95.6%) | NA |

| Erosions present on radiographs | NA | 21/38 (55.2%) | NA |

| Medication use | NA | ||

| Etanercept | 10 (19.6%) | NA | |

| Infliximab | 2 (3.9%) | NA | |

| Adalimumab | 5 (9.8%) | NA | |

| Abatacept | 5 (9.8%) | NA | |

| Methotrexate | 39 (76.5%) | NA | |

| Leflunomide | 1 (2.0%) | NA | |

| Sulfasalazine | 0 | NA | |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 10 (19.6%) | NA | |

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents | 18 (35.3%)* | 1 (4.0%) | |

| Prednisone (<5.0 mg/day) | 13 (25.5%) | NA | |

| Systemic inflammation | |||

| hsCRP (mg/L) | 3.0 (3.9) | 3.7 (4.9)* | 2.4 (2.9) |

| IL-1beta (pg/mL) | 0.23 (5.3) | 0.22 (4.1) | 0.17 (6.4) |

| IL-6 (pg/mL) | 4.9 (2.8) | 8.9 (2.9)* | 2.7 (1.6) |

| IL-8 (pg/mL) | 8.2 (2.1) | 8.9 (1.8) | 7.5 (2.3) |

| TNF-alpha (pg/mL) | 13.7 (2.3) | 19.9 (2.4)* | 9.5 (1.7) |

| IL-18 (pg/mL) | 408.3 (1.4) | 440.6 (1.3) | 379.3 (1.4) |

| Adiposity and muscle tissue | |||

| Abdominal total adipose area (cm2) | 427.9 (181.0) | 408.4 (199.5) | 447.3 (160.2) |

| Abdominal subcutaneous adiposity (cm2) | 303.3 (143.7) | 304.5 (154.2) | 302.1 (133.9) |

| Abdominal visceral adiposity (cm2) | 124.6 (93.2) | 104.0 (77.1)* | 145.2 (103.6) |

| Abdominal liver density (Hu) | 59.0 (11.6) | 59.7 (10.6) | 58.2 (12.9) |

| Thigh total area (cm2) | 249.6 (65.4) | 248.8 (73.6) | 251.7 (57.1) |

| Thigh total adipose area (cm2) | 250.2 (66.0) | 134.3 (65.8) | 110.9 (68.0) |

| Thigh subcutaneous adiposity (cm2) | 122.6 (67.6) | 122.6 (62.7) | 113.8 (54.0) |

| Thigh inter-muscular adiposity (cm2) | 11.3 (7.4) | 11.7 (6.7) | 11.0 (8.1) |

| Thigh muscle area (cm2) | 119.6 (35.1) | 114.5 (37.1) | 125.4 (32.1) |

| Thigh muscle density (Hu) | 54.0 (8.1) | 50.7 (6.2) | 55.4 (6.8) |

| Skeletal muscle inflammatory markers | |||

| IL-1β (pg/mL/mg) | 0.035 (0.084) | 0.037 (0.093) | 0.033 (0.069) |

| IL-6 (pg/mL/mg) | 0.012 (0.010) | 0.014 (0.010)* | 0.008 (0.007) |

| IL-8 (pg/mL/mg) | 0.139 (0.178) | 0.169 (0.211) | 0.097 (0.106) |

| TNF-α (pg/mL/mg) | 0.012 (0.015) | 0.014 (0.016) | 0.010 (0.014) |

| TLR4 (pg/mL/mg) | 0.891 (0.666) | 0.859 (0.692) | 0.937 (0.625) |

Data are presented as means (SD) for continuous variables and number (percentages) of participants for dichotomous variables. Data that were not normally distributed (systemic inflammatory markers and cytokines) are presented as geometric means (SD). Physical activity data reflect rheumatoid arthritis (RA) (n = 41) and controls (n = 31) with valid data. BMI body mass index, MET metabolic equivalents, HAQ health assessment questionnaire, DAS-28 disease activity score with 28-joint count, hsCRP high sensitivity C-reactive protein, IL interleukin, TNF tumor necrosis factor, Hu Houndsfield units, TLR toll-like receptor

* p < 0.05 for comparison with matched controls

Akin to disease activity, RA muscle inflammatory markers exhibited variation across a broad range (Table 1). Muscle inflammatory marker concentrations were positively associated with disease activity (mIL-1β, mIL-8), disability (mIL-1β, mIL-6), and pain (mIL-1β, mTNF-α, mTLR-4) (p < 0.05 for all) (Table 2). Muscle cytokines, mIL-1β and mIL-8, were negatively correlated with use of biological agents; mTNF-α was negatively correlated with use of non-biological disease-modifying therapy (p < 0.05 for all) (Table 2). Importantly, there were no correlation between muscle inflammatory marker concentrations and prednisone treatment.

Table 2.

Skeletal muscle inflammatory marker correlations in patients with rheumatoid arthritis

| Variable | Muscle IL-6 | Muscle IL-8 | Muscle TNF-α | Muscle IL-1β | Muscle TLR-4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | −0.07 | 0.05 | 0.09 | −0.09 | −0.29 * |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.24 | −0.05 | −0.23 | −0.10 | −0.25 |

| Disease activity (DAS28) | 0.23 | 0.30 * | 0.14 | 0.35 * | −0.01 |

| Disability (HAQ-DI) | 0.33 * | 0.19 | 0.09 | 0.33 * | 0.12 |

| Pain (VAS) | 0.15 | 0.17 | 0.29 * | 0.39 * | 0.47 * |

| Prednisone use (yes = 1) | 0.14 | −0.05 | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.01 |

| DMARD use (yes = 1) | −0.04 | −0.07 | −0.30 | 0.21 | 0.08 |

| Biologic use (yes = 1) | −0.25 | −0.37 * | 0.21 | −0.33 * | 0.01 |

| Comorbidity index | 0.17 | 0.12 | 0.17 | 0.26 | −0.08 |

| Plasma hsCRP (mg/L) | 0.20 | 0.07 | 0.11 | −0.03 | −0.17 |

| Plasma IL-1β (pg/mL) | 0.01 | −0.07 | −0.07 | −0.14 | −0.12 |

| Plasma IL-6 (pg/mL) | −0.03 | 0.11 | 0.12 | −0.01 | −0.10 |

| Plasma IL-8 (pg/mL) | −0.11 | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.02 |

| Plasma TNF-α (pg/mL) | −0.37 * | −0.15 | 0.02 | −0.23 | −0.08 |

| Plasma IL-18 (pg/mL) | −0.08 | −0.12 | −0.02 | −0.24 | 0.06 |

| GlycA (μmol/L) | 0.41 * | 0.38 * | −0.06 | 0.07 | −0.21 |

| HOMA | 0.11 | 0.04 | −0.06 | −0.10 | −0.07 |

| Insulin sensitivity (10-5.min-1/(pmol/L)) | −0.20 | −0.19 | −0.06 | −0.09 | −0.18 |

| Fasting insulin (mU/L) | 0.13 | 0.09 | −0.13 | −0.06 | −0.06 |

| Visceral adiposity (cm2) | 0.11 | 0.01 | −0.28 | 0.03 | −0.23 |

| Abdominal subcutaneous adiposity (cm2) | 0.21 | 0.06 | −0.19 | −0.06 | −0.19 |

| Total abdominal adiposity (cm2) | 0.19 | 0.07 | −0.24 | −0.06 | −0.28 |

| Thigh muscle density (Hu) | −0.04 | −0.10 | 0.06 | 0.16 | 0.28 * |

| Thigh inter-muscular adiposity (cm2) | 0.12 | 0.01 | −0.08 | −0.11 | −0.12 |

| Thigh subcutaneous adiposity (cm2) | 0.31 * | −0.07 | −0.11 | −0.09 | −0.11 |

| Exercise (min/day) | −0.40 * | −0.38 * | −0.05 | −0.38 * | −0.11 |

| Physical activity (MET h/day) | −0.33 * | −0.26 | 0.10 | −0.35 * | −0.15 |

Data are shown as Spearman correlation coefficients. BMI body mass index, DAS-28 disease activity score with 28 joint count, HAQ-DI health assessment questionnaire disability index, VAS visual analog scale, DMARD disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug (methotrexate, leflunomide, hydroxychlorquie), biologic biologic DMARD (adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, abatacept), hsCRP high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, IL interleukin, TNF tumor necrosis factor, HOMA homeostasis model assessment, Hu Houndsfield units, MET metabolic equivalent, TLR toll-like receptor. * p < 0.05 for Spearman correlation

In addition to disease-related factors, muscle cytokine concentrations (mIL-1β, mIL-6, and mIL-8) were negatively associated with exercise minutes (p < 0.05 for all) (Table 2). Higher mIL-1β and mIL-6 concentrations were associated with less total physical activity (total METs; p < 0.05 for both) (Table 2). Although, both mIL-6 and mIL-8 were positively correlated with the systemic inflammatory marker, GlycA (p < 0.05 for both) (Table 2), muscle inflammatory marker concentrations were not related to insulin sensitivity or systemic cytokine concentrations.

Skeletal muscle gene expression

To better understand the etiology of RA muscle inflammatory markers, we compared RA (n = 20) and control (n = 20) skeletal muscle gene expression: 1939 genes were significantly upregulated or downregulated in RA samples (p < 0.05); 445 genes were identified when using a more stringent definition of significance (p < 0.02).

To identify other relationships between differentially expressed RA muscle genes, pathway analyses were performed using IPA, which has thousands of canonical pathways onto which our experimental gene expression differences were overlaid. Of those canonical pathways, IPA identified several pathways impacted by differential gene expression in muscle in RA (p < 0.05) (Table 3). Except for glycolysis and methionine degradation, these canonical pathways were identified because of reduced RA muscle gene expression for nuclear factor (NF)-kβ2, both nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT)5 and NFATC4, or all three. Also, none of the canonical pathways was predicted to be activated or inhibited by gene expression differences in muscle in RA (Z-scores < |2|) (Table 3) [16].

Table 3.

Canonical pathways implicated in gene expression in muscle in rheumatoid arthritis

| Pathway | Dataset genesa in pathway (n) | Total genes in pathway (n) | Z-score | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wnt/Ca + pathway | 5 | 55 | 0 | 0.006 |

| Netrin signaling | 4 | 39 | NaN | 0.008 |

| Glycolysis | 3 | 24 | NaN | 0.013 |

| Atherosclerosis signaling | 7 | 121 | NaN | 0.013 |

| Altered T and B cell signaling in rheumatoid arthritis | 5 | 81 | NaN | 0.023 |

| Methionine degradation to homocysteine | 2 | 16 | NaN | 0.043 |

| PI3K signaling in B lymphocytes | 6 | 123 | −0.816 | 0.043 |

| April mediated signaling | 3 | 38 | NaN | 0.044 |

| B cell activating factor signaling | 3 | 40 | NaN | 0.049 |

aDataset genes were those differentially expressed between 20 patients with rheumatoid arthritis and 20 age, gender, and body mass index matched controls (p < 0.02). NaN Not a number

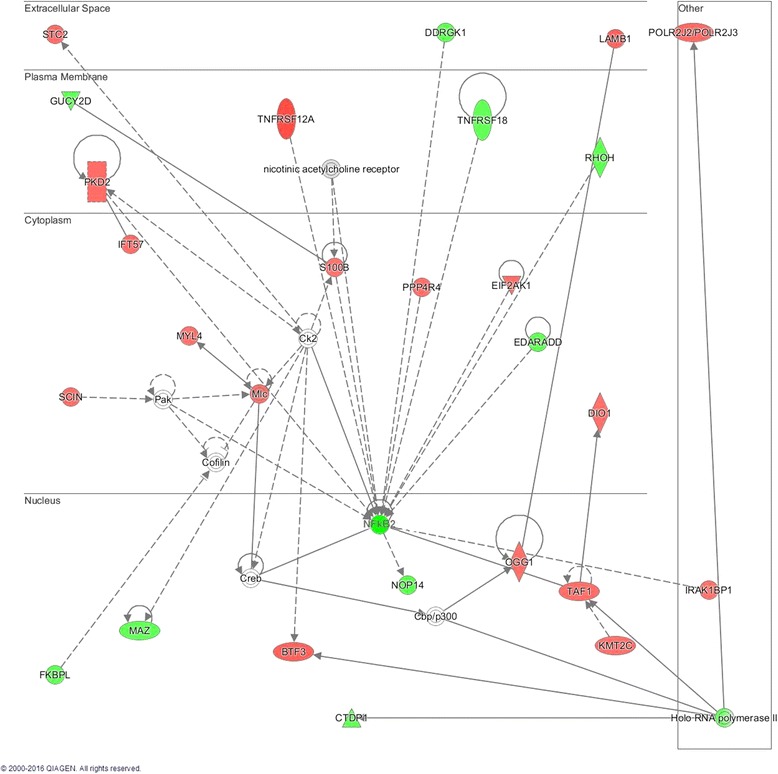

In addition to canonical networks, pathway analyses generate novel networks connecting differentially regulated molecules based on published associations. The IPA-generated novel network with the highest connection score depicted significant differences in expression of genes associated with connective tissue, dental, and dermatological diseases (Fig. 1; Table 4). The prominent pathway connections in muscle in RA were centered on regulation of the NF-kB complex, specifically NF-kB2. These were in the setting of differential regulation of genes in muscle repair and glycolysis.

Fig. 1.

Novel network identified by muscle gene expression in rheumatoid arthritis (RA): gene expression was determined in muscle from 20 persons with RA and 20 controls matched by age, gender, and body mass index. The network shows connections between genes with differential expression in RA relative to control muscle. Genes in red were upregulated and genes in green were downregulated in muscle in RA

Table 4.

Novel network genes

| Gene ID | Gene name | RA vs. CONTROL | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fold change | p value | ||

| BTF3 | Basic transcription factor 3 | 1.11 | 0.003 |

| CTDP1 | CTD (carboxy-terminal domain, RNA polymerase II, polypeptide A) phosphatase, subunit 1 | −1.04 | 0.006 |

| DDRGK1 | DDRGK domain containing 1 | −1.07 | 0.02 |

| DIO1 | Deiodinase, iodothyronine, type I | 1.03 | 0.005 |

| EDARADD | EDAR-associated death domain | −1.06 | 0.007 |

| EIF2AK1 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2-alpha kinase 1 | 1.05 | 0.007 |

| FKBPL | FK506 binding protein like | −1.06 | 0.003 |

| GUCY2D | Guanylate cyclase 2D, membrane (retina-specific) | −1.04 | 0.004 |

| IFT57 | Intraflagellar transport 57 | 1.04 | 0.01 |

| IRAK1BP1 | Interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase 1 binding protein 1 | 1.02 | 0.02 |

| KMT2C | Lysine (K)-specific methyltransferase 2C | 1.03 | 0.01 |

| LAMB1 | Laminin, beta 1 | 1.11 | 0.02 |

| MAZ | MYC-associated zinc finger protein (purine-binding transcription factor) | −1.03 | 0.008 |

| MYL4 | Myosin, light chain 4, alkali; atrial, embryonic | 1.02 | 0.01 |

| NFkB2 | Nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells 2 (p52/p100) | −1.06 | 0.003 |

| NOP14 | NOP14 nucleolar protein | −1.08 | 0.008 |

| OGG1 | 8-Oxoguanine DNA glycosylase | 1.03 | 0.002 |

| PKD2 | Polycystic kidney disease 2 (autosomal dominant) | 1.05 | 0.02 |

| POLR2J2/POLR2J3 | Polymerase (RNA) II (DNA directed) polypeptide J3 | 1.08 | 0.004 |

| PPP4R4 | Protein phosphatase 4, regulatory subunit 4 | 1.03 | 0.006 |

| RHOH | Ras homolog family member H | −1.06 | 0.002 |

| S100B | S100 calcium binding protein B | 1.02 | 0.02 |

| SCIN | Scinderin | 1.04 | 0.001 |

| STC2 | Stanniocalcin 2 | 1.04 | 0.008 |

| TAF1 | TAF1 RNA polymerase II, TATA box binding protein (TBP)-associated factor, 250 kDa | 1.04 | 0.02 |

| TNFRSF12A | Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 12A; TNF-like weak inducer of apoptosis (TWEAK) receptor | 1.24 | 0.01 |

| TNFRSF18 | Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 18 | −1.02 | 0.005 |

To augment traditional pathway analyses, we evaluated the 20 genes with the largest muscle expression differences in RA and control samples (Table 5) and examined gene members of well-established skeletal muscle anabolic, catabolic, and inflammatory pathways (Table 6). The top 20 upregulated and downregulated genes by fold difference were associated with muscle remodeling, satellite cell maturation, exercise intolerance, and/or energy metabolism; for these genes, the range of differences in expression was 20–50% (Table 5). Except for NF-kB2, there was no differential expression of canonical genes involved in skeletal muscle anabolic, catabolic, or inflammatory pathways (Table 6).

Table 5.

Genes with the greatest differences in expression between patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and controls

| Gene ID | Gene name and description | Fold change | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Upregulated in RA | |||

| OTUD1 | OUT deubiquitinase 1: removes ubiquitin molecules with probable signaling regulatory role | 1.50 | 0.035 |

| FEZ2a | Fasciculation and elongation protein zeta 2 (zygin II): reduces autophagy [32]; associated with reduced cardiorespiratory fitness [33] | 1.40 | 0.005 |

| PITX1a | Paired-like homeodomain 1: promotes muscle atrophy [34] | 1.37 | 0.046 |

| RNU4ATAC | RNA, U4atac small nuclear (U12-dependent splicing): codes for component of the minor spliceosome [35, 36] | 1.36 | 0.045 |

| ABRAa | Actin binding Rho activating protein: promotes myoblast differentiation and myotube maturation [24] | 1.33 | 0.031 |

| RCAN1a | Regulator of calcineurin 1: regulates fiber type patterning during differentiation | 1.32 | 0.019 |

| CITED2a | Cbp/p300-interacting transactivator, with Glu/Asp-rich carboxy-terminal domain, 2: promotes stem cell maintenance [22, 23]; prevents myofibril degradation [37] | 1.32 | 0.027 |

| VGLL2a | Vestigial-like family member 2: expressed in myotubes [27] | 1.30 | 0.035 |

| MYF6a | Myogenic factor 6 (herculin): promotes myoblast terminal differentiation [29] | 1.27 | 0.033 |

| RPL36AL | Ribosomal protein L36a-like: ribosomal protein with ability to terminate translation in certain situations [38] | 1.27 | 0.011 |

| Downregulated in RA | |||

| FBP2b | Fructose-1,6 bisphosphatase 2: promotes glycogen storage [39, 40]; protects mitochondria from Ca2+ -induced injury [41] | −1.42 | 0.013 |

| MYLK4a | Myosin light chain kinase family, member 4: reduced expression associated with cardiomyopathies [42] | −1.37 | 0.024 |

| ZFP36ac | ZFP36 ring finger protein; encodes tristetraprolin (TTP): reduces inflammation and prevents satellite cell activation [20] | −1.36 | 0.023 |

| DDIT4a | DNA damage-inducible transcript 4; also known as protein regulated in development and damage response 1 (REDD-1): promotes autophagy, with reduced expression associated with exercise intolerance [43] | −1.34 | 0.023 |

| MIDNb | Midnolin: regulates neurogenesis [44]; reduces pancreatic glycolysis in low glucose states [45] | −1.32 | 0.017 |

| SLC2A5b | Solute carrier family 2 (facilitated glucose/fructose transporter), member 5: performs facilitative fructose uptake into muscle [46] | −1.31 | 0.041 |

| SLC25A25b | Solute carrier family 25 (mitochondrial carrier; phosphate carrier), member 25: promotes anti-atherosclerotic macrophage ATP production [47]; promotes muscle ATP production and physical endurance [48] | −1.30 | 0.013 |

| RRADa | Ras-related associated with diabetes: increases myoblast proliferation and promotes myotube formation [30] | −1.30 | 0.044 |

| ZBTB16bc | Zinc ring finger and BTB domain containing 16: suppresses autoreactive T cells and inflammation [21]; promotes adaptive thermogenesis and mitochondrial capacity [49] | −1.27 | 0.050 |

| SMTNL2 | Smoothelin-like 2: associated with myotube formation [50] | −1.22 | 0.008 |

aGenes associated with muscle remodeling, satellite cell maturation, or exercise intolerance. See Additional file 1 for more details. bGenes associated with metabolism

cGenes associated with immune and inflammatory responses

Table 6.

Genes involved in skeletal muscle anabolic, catabolic, and inflammatory pathways

| Gene ID | Gene name | Rheumatoid arthritis vs. control | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fold change | p value | ||

| Ubiquitin-proteasome pathway | |||

| MuRF1 | Muscle RING-finger protein-1 | −1.02 | 0.25 |

| MuRF2 | Muscle-specific RING finger-2 | −1.01 | 0.47 |

| FbxO32 | F-box protein 32 | 1.02 | 0.88 |

| FbxO40 | F-box protein 40 | −1.03 | 0.37 |

| Autophagy-lysozyme pathway | |||

| Atg5 | Autophagy related 5 | −1.01 | 0.77 |

| Atg7 | Autophagy related 7 | −1.09 | 0.13 |

| NAF1 | Nuclear assembly factor 1 ribonucleoprotein | −1.03 | 0.12 |

| Lamp2 | Lysosomal-associated membrane protein 2 | −1.03 | 0.65 |

| IGF1/Akt signaling pathway | |||

| IGF1 | Insulin-like growth factor 1 | 1.00 | 0.85 |

| Akt1 | V-Akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homolog 1 | 1.00 | 0.92 |

| Akt2 | V-Akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homolog 2 | −1.04 | 0.41 |

| Rptor | Regulatory associated protein of MTOR, complex 1 | 1.02 | 0.45 |

| Rictor | RPTOR independent companion of MTOR, complex 2 | 1.01 | 0.54 |

| FoxO1 | Forkhead box O1 | −1.07 | 0.34 |

| FoxO3 | Forkhead box O3 | −1.09 | 0.39 |

| TGFbeta/Myostatin signaling pathway | |||

| ActRIIIB | ARP3 actin-related protein 3 homolog B | 1.02 | 0.69 |

| FST | Follistatin | −1.02 | 0.30 |

| NFkB signaling pathways | |||

| IKBKB | Inhibitor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B cells, kinase beta | −1.08 | 0.17 |

| IKBKAP | Inhibitor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B cells, kinase complex-associated protein | 1.001 | 0.43 |

| TRAF6 | TNF receptor-associated factor 6, E3 ubiquitin protein ligase | 1.02 | 0.37 |

| TRADD | TNFRSF1A-associated via death domain | −1.02 | 0.46 |

| Bcl3 | B-Cell CLL/lymphoma 3 | −1.02 | 0.32 |

| TRAF2 | TNF receptor-associated factor 2 | −1.00 | 0.95 |

| TRAF5 | TNF receptor-associated factor 5 | 1.01 | 0.37 |

| MAPK8 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase 8 | −1.01 | 0.32 |

| NFkB1 | Homo sapiens nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B cells 1 (p105/p50) | −1.00 | 0.97 |

| NFkB2 | Homo sapiens nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B cells 2 (p52/p100) | −1.06 | 0.003 |

Skeletal muscle metabolic intermediates

When concentrations of skeletal muscle metabolic intermediates were compared between RA (n = 51) and controls (n = 51), muscle pyruvate concentrations were 46% greater in muscle in RA than in controls (p < 0.001) (Table 7). There were no significant differences in the concentrations of muscle amino acids, other organic acids, or acylcarnitines in RA compared to controls (Table 7). However, several muscle amino acids and acylcarnitines were related to RA disease activity and disability. For instance, greater concentrations of glycine, serine, aspartate/asparagine, and ornithine and lower muscle concentrations of alanine and fumarate were related to greater disease activity (p < 0.05) (Table 8). Greater muscle concentrations of glycine, proline, ornithine, arginine, and aspartate/asparagine were related to greater disability (p < 0.05) (Fig. 2); in contrast, lower concentrations of several long-chain unsaturated acylcarnitines were related to greater disease activity and disability (p < 0.05) (Table 8).

Table 7.

Skeletal muscle metabolic intermediate concentrations

| Rheumatoid arthririts (n = 51) | Controls (n = 50) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Amino acids | ||||

| Glycine | 1012.669 | 304.568 | 1042.875 | 360.089 |

| Alanine | 2781.241 | 876.247 | 2735.464 | 820.802 |

| Serine | 773.987 | 190.246 | 777.726 | 286.455 |

| Proline | 502.861 | 179.5 | 528.023 | 222.984 |

| Valine | 291.82 | 75.004 | 300.739 | 99.003 |

| Leucine/isoleucine | 659.544 | 197.996 | 663.116 | 233.404 |

| Methionine | 54.167 | 14.36 | 55.372 | 17.48 |

| Histidine | 488.821 | 164.605 | 548.187 | 276.048 |

| Phenylalanine | 77.739 | 22.414 | 80.155 | 27.759 |

| Tyrosine | 80.962 | 23.249 | 88.815 | 32.052 |

| Aspartate/asparagine | 100.518 | 62.088 | 144.672 | 198.704 |

| Glutamate/glutamine | 2096.524 | 658.272 | 2359.04 | 878.482 |

| Ornithine | 212.338 | 85.775 | 184.849 | 69.873 |

| Citrulline | 69.446 | 39.718 | 75.05 | 50.441 |

| Arginine | 431.024 | 182.215 | 394.565 | 149.594 |

| Organic acids | ||||

| Lactate | 22862.683 | 9246.29 | 20956.576 | 8926.553 |

| Pyruvate | 1168.544* | 604.675 | 803.474 | 539.098 |

| Succinate | 48.143 | 35.538 | 41.793 | 29.968 |

| Fumarate | 70.313 | 26.403 | 62.708 | 25.253 |

| Malate | 521.019 | 205.905 | 476.648 | 198.079 |

| alphaKetoglutarate | 144.24 | 143.952 | 113.438 | 118.669 |

| Citrate | 41.677 | 33.591 | 36.853 | 24.096 |

| Acylcarnitines | ||||

| Free carnitine: C0 | 3369.034 | 1006.646 | 3631.978 | 1243.598 |

| C2 | 455.175 | 288.39 | 485.702 | 312.966 |

| C3 | 5.206 | 2.024 | 5.019 | 2.018 |

| C4/Ci4 | 3.541 | 4.994 | 3.008 | 2.594 |

| C5:1 | 1.033 | 0.397 | 1.03 | 0.41 |

| C5 | 1.667 | 1.15 | 2.246 | 5.666 |

| C4OH | 2.789 | 2.231 | 2.378 | 1.778 |

| C6 | 3.58 | 3.882 | 2.956 | 2.855 |

| C5OH | 0.676 | 0.363 | 0.65 | 0.343 |

| C3DC | 0.793 | 0.356 | 0.809 | 0.292 |

| C4DC/Ci4DC | 2.439 | 1.424 | 2.547 | 1.192 |

| C8:1 | 0.531 | 0.328 | 0.532 | 0.252 |

| C8 | 0.942 | 0.904 | 0.826 | 0.694 |

| C5DC | 1.528 | 1.043 | 1.43 | 0.727 |

| C8:1OH/C6:1 DC | 0.216 | 0.129 | 0.204 | 0.123 |

| C6DC/C8OH | 0.353 | 0.239 | 0.388 | 0.226 |

| C10:3 | 0.067 | 0.047 | 0.067 | 0.034 |

| C10:2 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.063 | 0.041 |

| C10:1 | 0.261 | 0.253 | 0.239 | 0.164 |

| C10 | 0.655 | 0.6 | 0.58 | 0.48 |

| C7DC | 0.108 | 0.079 | 0.088 | 0.049 |

| C8:1 DC | 0.087 | 0.073 | 0.093 | 0.051 |

| C10OH:C8DC | 0.305 | 0.253 | 0.31 | 0.21 |

| C12:2 | 0.052 | 0.034 | 0.052 | 0.035 |

| C12:1 | 0.364 | 0.281 | 0.366 | 0.287 |

| C12 | 1.359 | 1.073 | 1.31 | 1.125 |

| C12:2OH/C10:2 DC | 0.075 | 0.045 | 0.064 | 0.04 |

| C12:1OH/C10:1 DC | 0.224 | 0.178 | 0.202 | 0.114 |

| C12OH/C10DC | 0.441 | 0.472 | 0.417 | 0.382 |

| C14:3 | 0.078 | 0.052 | 0.073 | 0.054 |

| C14:2 | 1.126 | 1.025 | 0.902 | 0.83 |

| C14:1 | 2.726 | 2.354 | 2.449 | 2.232 |

| C14 | 4.156 | 3.277 | 3.781 | 3.373 |

| C14:3OH/C12:3 DC | 0.032 | 0.025 | 0.028 | 0.022 |

| C14:2OH/C12:2 DC | 0.174 | 0.121 | 0.143 | 0.081 |

| C14:1OH/C12:1 DC | 0.704 | 0.538 | 0.701 | 0.431 |

| C14OH/C12DC | 0.502 | 0.525 | 0.487 | 0.381 |

| C16:3 | 0.198 | 0.164 | 0.157 | 0.103 |

| C16:2 | 1.533 | 1.201 | 1.199 | 0.948 |

| C16:1 | 6.736 | 5.227 | 5.751 | 3.973 |

| C16 | 20.041 | 15.253 | 17.878 | 12.497 |

| C16:3OH/C14:3-DC | 0.053 | 0.038 | 0.045 | 0.024 |

| C16:2OH/C14:2 DC | 0.477 | 0.336 | 0.412 | 0.248 |

| C16:1OH/C14:1 DC | 1.306 | 1.077 | 1.256 | 0.834 |

| C16OH/C14DC | 1.18 | 1.265 | 1.229 | 1.059 |

| C18:3 | 1.463 | 0.982 | 1.354 | 0.925 |

| C18:2 | 20.561 | 15.909 | 17.722 | 13.495 |

| C18:1 | 46.521 | 37.117 | 40.451 | 28.311 |

| C18 | 11.278 | 8.401 | 10.817 | 8.203 |

| C18:3OH/C16:3 DC | 0.186 | 0.158 | 0.168 | 0.101 |

| C18:2OH/C16:2 DC | 1.357 | 1.235 | 1.323 | 1.177 |

| C18:1OH/C16:1 DC | 2.683 | 2.889 | 2.844 | 2.749 |

| C18OH/C16DC | 0.695 | 0.68 | 0.732 | 0.523 |

| C20:4 | 2.023 | 1.801 | 1.778 | 1.872 |

| C20:3 | 0.63 | 0.597 | 0.57 | 0.431 |

| C20:2 | 0.308 | 0.271 | 0.261 | 0.164 |

| C20:1 | 0.554 | 0.484 | 0.485 | 0.409 |

| C20 | 0.369 | 0.4 | 0.329 | 0.308 |

| C20:3OH/C18:3 DC | 0.075 | 0.059 | 0.074 | 0.056 |

| C20:2OH/C18:2 DC | 0.053 | 0.034 | 0.05 | 0.03 |

| C20:1OH/C18:1 DC | 0.071 | 0.062 | 0.062 | 0.046 |

| C20OHC18DC/C22:6 | 0.212 | 0.248 | 0.198 | 0.206 |

| C22:5 | 0.264 | 0.299 | 0.247 | 0.277 |

| C22:4 | 0.241 | 0.279 | 0.193 | 0.158 |

| C22:3 | 0.064 | 0.057 | 0.056 | 0.044 |

| C22:2 | 0.051 | 0.035 | 0.044 | 0.025 |

| C22:1 | 0.069 | 0.05 | 0.065 | 0.038 |

| C22 | 0.059 | 0.049 | 0.062 | 0.046 |

Data are shown as means and standard deviations (pmol/mg tissue). Metabolic intermediates were measured in muscle homogenates. Group comparisons between muscle from patients with rheumatoid arthritis and from controls were performed using logarithmically transformed metabolic intermediates and mixed models. Prefix C denotes acylcarnitines followed by carbon number and degree of unsaturation. Suffixes OH and DC denote hydroxyl and dicarboxyl groups, respectively. *P < 0.05 for comparison with matched controls

Table 8.

Relationships between rheumatoid arthritis clinical features and muscle metabolic intermediates

| Disease activity | Disability | Pain | Exercise (min/d) | Physical activity (MET h/d) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amino acids | |||||

| Glycine | 0.33b | 0.50a | 0.23 | 0.11 | 0.02 |

| Alanine | -0.31b | 0.03 | -0.01 | 0.11 | 0.08 |

| Serine | 0.31b | 0.20 | 0.17 | -0.03 | -0.01 |

| Proline | 0.20 | 0.36a | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.08 |

| Valine | 0.12 | 0.11 | -0.04 | 0.05 | -0.01 |

| Leucine/isoleucine | 0.09 | 0.18 | -0.01 | -0.08 | -0.16 |

| Methionine | 0.07 | 0.16 | -0.17 | -0.01 | -0.04 |

| Histidine | -0.08 | -0.02 | -0.12 | 0.23 | 0.19 |

| Phenylalanine | -0.06 | -0.04 | -0.21 | 0.06 | 0.04 |

| Tyrosine | -0.06 | 0.08 | -0.13 | 0.13 | 0.14 |

| Aspartate/asparagine | 0.34b | 0.36a | 0.20 | -0.13 | -0.12 |

| Glutamate/glutamine | 0.20 | 0.24 | 0.06 | -0.12 | -0.04 |

| Ornithine | 0.32b | 0.39a | 0.14 | -0.21 | -0.20 |

| Citrulline | 0.08 | 0.21 | 0.13 | -0.02 | 0.13 |

| Arginine | 0.27 | 0.45a | 0.24 | -0.26 | -0.27 |

| Organic acids | |||||

| Lactate | -0.09 | -0.18 | -0.06 | -0.09 | -0.12 |

| Pyruvate | -0.22 | -0.22 | -0.21 | 0.16 | 0.05 |

| Succinate | 0.03 | -0.01 | 0.15 | -0.06 | -0.12 |

| Fumarate | -0.34b | -0.24 | -0.15 | 0.05 | -0.01 |

| Malate | -0.28 | -0.14 | 0.04 | -0.01 | -0.07 |

| alphaKetoglutarate | -0.22 | -0.03 | -0.03 | 0.27 | 0.18 |

| Citrate | 0.17 | 0.23 | 0.29 | 0.05 | 0.14 |

| Acylcarnitines | |||||

| Free carnitine: C0 | -0.10 | 0.19 | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.08 |

| C2 | -0.07 | 0.08 | 0.07 | -0.22 | -0.02 |

| C3 | -0.05 | 0.10 | -0.01 | 0.10 | 0.00 |

| C4/Ci4 | -0.02 | -0.13 | -0.20 | 0.09 | 0.16 |

| C5:1 | 0.15 | 0.09 | 0.06 | -0.10 | 0.05 |

| C5 | 0.01 | 0.05 | -0.24 | 0.14 | 0.10 |

| C4OH | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.11 | -0.11 | -0.04 |

| C6 | 0.05 | -0.10 | -0.24 | 0.30 | 0.29 |

| C5OH | -0.24 | 0.04 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.25 |

| C3DC | -0.17 | 0.13 | 0.03 | -0.02 | 0.10 |

| C4DC/Ci4DC | 0.02 | 0.28b | 0.05 | -0.32b | -0.23 |

| C8:1 | -0.10 | -0.05 | -0.15 | -0.07 | 0.00 |

| C8 | 0.01 | -0.11 | -0.13 | 0.16 | 0.13 |

| C5DC | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.03 | -0.12 | -0.11 |

| C8:1OH/C6:1 DC | 0.11 | 0.21 | 0.12 | -0.05 | -0.11 |

| C6DC/C8OH | -0.02 | 0.03 | -0.10 | 0.08 | 0.11 |

| C10:3 | 0.02 | 0.15 | 0.15 | -0.10 | -0.09 |

| C10:2 | 0.00 | 0.06 | -0.05 | -0.14 | -0.20 |

| C10:1 | -0.09 | -0.09 | -0.08 | 0.19 | 0.11 |

| C10 | -0.05 | -0.12 | -0.13 | 0.15 | 0.14 |

| C7DC | 0.04 | 0.13 | 0.06 | -0.20 | -0.20 |

| C8:1 DC | -0.17 | -0.03 | -0.13 | -0.06 | -0.09 |

| C10OH:C8DC | -0.08 | 0.00 | -0.15 | 0.06 | 0.07 |

| C12:2 | 0.04 | -0.01 | -0.08 | -0.24 | -0.26 |

| C12:1 | -0.14 | -0.12 | -0.13 | 0.14 | 0.12 |

| C12 | -0.20 | -0.22 | -0.19 | 0.20 | 0.19 |

| C12:2OH/C10:2 DC | -0.19 | -0.03 | -0.14 | 0.06 | 0.00 |

| C12:1OH/C10:1 DC | -0.19 | -0.07 | -0.16 | 0.15 | 0.18 |

| C12OH/C10DC | -0.16 | 0.03 | -0.13 | 0.13 | 0.14 |

| C14:3 | -0.14 | -0.09 | -0.15 | 0.19 | 0.20 |

| C14:2 | -0.22 | -0.17 | -0.22 | 0.27 | 0.26 |

| C14:1 | -0.18 | -0.16 | -0.17 | 0.21 | 0.21 |

| C14 | -0.25 | -0.21 | -0.26 | 0.24 | 0.22 |

| C14:3OH/C12:3 DC | -0.05 | 0.08 | -0.01 | -0.03 | 0.12 |

| C14:2OH/C12:2 DC | -0.12 | -0.03 | -0.20 | 0.04 | 0.03 |

| C14:1OH/C12:1 DC | -0.24 | -0.11 | -0.19 | 0.14 | 0.17 |

| C14OH/C12DC | -0.13 | 0.03 | -0.14 | 0.16 | 0.17 |

| C16:3 | -0.28 | -0.19 | -0.22 | 0.26 | 0.27 |

| C16:2 | -0.34b | -0.26 | -0.26 | 0.35a | 0.33b |

| C16:1 | -0.28 | -0.22 | -0.17 | 0.22 | 0.18 |

| C16 | -0.27 | -0.20 | -0.19 | 0.17 | 0.18 |

| C16:3OH/C14:3-DC | -0.16 | -0.10 | -0.03 | 0.11 | 0.19 |

| C16:2OH/C14:2 DC | -0.26 | -0.16 | -0.19 | 0.12 | 0.10 |

| C16:1OH/C14:1 DC | -0.25 | -0.09 | -0.21 | 0.10 | 0.12 |

| C16OH/C14DC | -0.17 | 0.04 | -0.08 | 0.10 | 0.12 |

| C18:3 | -0.43a | -0.36a | -0.19 | 0.20 | 0.19 |

| C18:2 | -0.40a | -0.39a | -0.19 | 0.23 | 0.18 |

| C18:1 | -0.33b | -0.32b | -0.15 | 0.15 | 0.13 |

| C18 | -0.21 | -0.13 | -0.12 | 0.06 | 0.09 |

| C18:3OH/C16:3 DC | -0.29 | -0.06 | -0.02 | 0.18 | 0.18 |

| C18:2OH/C16:2 DC | -0.31b | -0.06 | -0.08 | 0.12 | 0.14 |

| C18:1OH/C16:1 DC | -0.22 | 0.02 | -0.04 | 0.06 | 0.07 |

| C18OH/C16DC | -0.18 | 0.03 | -0.08 | -0.03 | 0.00 |

| C20:4 | -0.28 | -0.30b | -0.12 | 0.26 | 0.27 |

| C20:3 | -0.29b | -0.37a | -0.11 | 0.18 | 0.17 |

| C20:2 | -0.25 | -0.20 | -0.14 | 0.11 | 0.14 |

| C20:1 | -0.25 | -0.16 | -0.11 | 0.07 | 0.08 |

| C20 | -0.18 | -0.04 | -0.09 | -0.02 | -0.01 |

| C20:3OH/C18:3 DC | 0.09 | 0.21 | -0.01 | -0.14 | -0.08 |

| C20:2OH/C18:2 DC | -0.16 | -0.15 | 0.06 | -0.14 | -0.14 |

| C20:1OH/C18:1 DC | -0.03 | 0.18 | -0.03 | 0.00 | 0.04 |

| C20OHC18DC/C22:6 | -0.16 | 0.00 | -0.09 | -0.05 | -0.08 |

| C22:5 | -0.28 | -0.20 | -0.14 | 0.15 | 0.09 |

| C22:4 | -0.22 | -0.24 | -0.06 | 0.07 | 0.09 |

| C22:3 | -0.03 | -0.11 | 0.01 | -0.06 | -0.03 |

| C22:2 | 0.13 | -0.01 | -0.06 | 0.09 | 0.24 |

| C22:1 | 0.06 | 0.01 | -0.12 | 0.28 | 0.36 |

| C22 | -0.02 | -0.06 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.10 |

Data are shown as Spearman correlation coefficients. aSignificant relationships (p < 0.05) to all red and green color and bSignificant relationships r ≥ |0.35| to all bright red and green

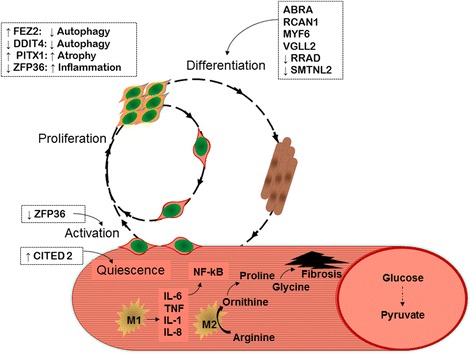

Fig. 2.

Schematic depiction of muscle injury repair showing potential impact of cytokine, gene expression, and amino acids on satellite cell activation, macrophage function, and fibrosis in muscle from patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Boxes show gene IDs for genes differentially regulated in patients with RA and in controls. See Table 3 for gene descriptions

Discussion

Here, we report that in RA, skeletal muscle exhibits molecular alterations in inflammatory markers, transcriptional profiles, and metabolic signatures. Both at protein and transcriptional levels, muscle had a pro-inflammatory phenotype in RA. Additionally, differential gene expression in muscle in RA was indicative of dysregulation of muscle repair, promotion of glycolysis, and poor mitochondrial function. Upregulated glycolysis and mitochondrial inefficiency were supported by greater muscle concentrations of the glycolytic end-product pyruvate in RA. Further, disease activity and disability were related to lesser concentrations of long-chain acylcarnitines and greater concentrations of amino acid precursors for muscle fibrosis. Taken together, these alterations in proteins, gene expression, and metabolic intermediates were indicative of muscle in RA in a state of chronically activated, yet dysregulated remodeling with increased glycolysis, mitochondrial inefficiency, and fibrotic material (Fig. 2).

This represents the first report of significant markers of inflammation in muscle in RA. The clinical importance of these molecules is demonstrated by the significant association of several muscle cytokines with RA disease activity, disability, pain, and physical inactivity. The IPA-generated novel network centered on downregulation of NF-kB2, a protein that promotes non-canonical NF-kB signaling and opposes inflammatory signaling [17]. Downregulation of NF-kB2 would be predicted to favor coordinated upregulation of pro-inflammatory NF-kB signaling in muscle in RA. We were unable to determine if the muscle cytokines and pro-inflammatory transcripts in RA were derived from myocytes, inflammatory cells, or other cellular sources. Interestingly, muscle cytokine concentrations did not reflect those measured in circulation, suggesting these disease-associated inflammatory markers stem from local rather than systemic events.

Based on the strong relationships between muscle inflammatory markers and disability, pain and physical inactivity, we suspected that increased intramuscular cytokines may be indicative of a disrupted muscle remodeling process. In fact, muscle gene expression alterations in RA were consistent with promotion of satellite cell differentiation and upregulation of several facets of the normally well-coordinated process of muscle remodeling. For instance, muscle in RA was characterized by downregulation of ZFP36, the gene that encodes tristetraprolin (TTP), which reduces inflammation by destabilizing pro-inflammatory cytokine transcripts [18, 19] and prevents satellite cell activation by destabilizing myogenic regulatory factor, MyoD, mRNA [20]. Thus, the reduction in ZFP36 expression in muscle in RA would be expected to promote pro-inflammatory cytokine production and satellite cell activation.

Other gene expression changes also suggest both chronic activation and temporal dysregulation of muscle remodeling. For instance, downregulation of ZBTB16 would promote inflammation and proliferation of autoreactive T cells [21]. In contrast to the reduced ZFP36 expected to promote satellite cell activation, the increased CITED2 would be expected to reduce satellite cell activation [22, 23]. Increased expression of ABRA, RCAN1, VGLL2, MYF6 and decreased expression of RRAD would promote differentiation of satellite cells [24–30]. More descriptions of differentially expressed genes are provided in Additional file 1.

Gene expression alterations indicative of glycolysis promotion and poor mitochondrial function were supported by greater muscle concentrations of the glycolytic end-product pyruvate in RA. Further, disease activity and disability were related to lower concentrations of fatty-acid-derived long-chain acylcarnitines. One plausible explanation for this relationship is that fewer long-chain acylcarnitines indicate less oxidative metabolism and fewer mitochondria, consistent with a glycolytic phenotype. RA disease activity and disability were also related to higher concentrations of amino acid precursors for muscle fibrosis. M2-type macrophages contain arginase, which metabolizes arginine to ornithine [31]. Ornithine is converted to proline, which provides a substrate for resident fibroblasts to generate collagen. In addition to proline, collagen formation also requires glycine; glycine and proline each account for a third of the collagen amino acids. While collagen is critical for extracellular matrix production, in the setting of a chronically activated remodeling process, excess collagen production leads to fibrosis [31]. Thus, the relationships between these amino acids and disease activity and disability may indicate a fibrotic process in muscle associated with active disease that contributes to RA-associated disability.

There were several limitations to this study. RA medication regimens were not uniform among participants, and effects of these medications on skeletal muscle are unclear. Twenty-five percent of patients with RA used prednisone at low doses, which is not expected to have significant myopathic effects; despite this, they had significant alterations in muscle inflammatory markers and systemic inflammation relative to controls. Without histopathologic assessment or single cell isolations, we were unable to determine the cellular source of muscle cytokines, transcripts, or metabolites. Our findings indicate that either RA medication regimens or the RA disease process itself alters skeletal muscle inflammatory molecules, transcriptional profiles, and metabolic pathways.

Conclusions

Taken together, these alterations in pro-inflammatory cytokines, gene expression, and metabolic intermediates are indicative of RA muscle in a state of chronically activated, yet dysregulated remodeling, with increased glycolysis, mitochondrial inefficiency, and fibrosis. It is very likely these changes contribute to the ongoing issues of exercise intolerance and disability in persons with RA. Future work should be directed at understanding whether these deficits may be mitigated by combining pharmacologic treatment with physical activity, to reduce inflammatory signaling and/or fibrosis while promoting skeletal muscle efficiency. Therefore, to improve the lives of patients with RA, future work should be directed toward understanding the role of skeletal muscle in RA, and interactions between treatment regimens, physical activity, and influences of skeletal muscle on the clinical status in RA.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by NIH/NIAMS K23AR054904; a pilot project part of NIH/NIA P30AG028716; an Early Career Development Award from the Central Society of Clinical Research; and an ACR-REF/ASP Junior Career Development Award in Geriatric Medicine funded via Atlantic Philanthropies, ACR-REF, John A. Hartford Foundation and ASP. LipoScience, Inc. (now LabCorp) provided GlycA determinations at no cost.

Availability of data and materials

All data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Authors’ contributions

KMH, RJ, BA, BND, and MJH contributed to the data analysis and data interpretation, and wrote the manuscript. RN, JLH, JM, BFG, KNT, and MC participated in acquisition of data and laboratory studies, and reviewed/edited the manuscript. VBK, TRK, DMM, and WEK participated in conceptual design and data interpretation, and reviewed/edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration and was approved (Protocol 7701) by the Duke University Institutional Review Board. We obtained written informed consent from all study participants prior to all study activities.

Abbreviations

- BMI

body mass index

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- DAS-28

disease activity score

- DMARD

disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- HAQ-DI

health assessment questionnaire-disability index

- HOMA

homeostasis model assessment

- hsCRP

high sensitivity C-reactive protein

- Hu

Houndsfield units

- IL

interleukin

- IPA

Ingenuity Pathway Analysis

- LC

liquid chromatography

- m

muscle

- MET

metabolic equivalent

- MS

mass spectrometry

- NaN

not a number

- NF-kβ

nuclear factor-kβ

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- RA

rheumatoid arthritis

- TLR

toll-like receptor

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor-alpha

- TTP

tristetraprolin

- VAS

visual analog scale

Additional file

Supplemental gene information. Additional detail on genes that were most differentially expressed in muscle from patients with rheumatoid arthritis and from control participants. Genes are described and categorized by the proposed function of their respective gene products (DOCX 88 kb)

Contributor Information

Kim M. Huffman, Email: Huffm007@mc.duke.edu

Ryan Jessee, Email: ryan.jessee@duke.edu.

Brian Andonian, Email: brian.andonian@duke.edu.

Brittany N. Davis, Email: Brittany.n.davis@duke.edu

Rachel Narowski, Email: rachelnarowski@gmail.com.

Janet L. Huebner, Email: janet.huebner@dm.duke.edu

Virginia B. Kraus, Email: kraus004@duke.edu

Julie McCracken, Email: mccracken.julie@gmail.com.

Brian F. Gilmore, Email: brian.gilmore@duke.edu

K. Noelle Tune, Email: kntune19@yahoo.com.

Milton Campbell, Email: Campbellmilton@gmail.com.

Timothy R. Koves, Email: tim.koves@duke.edu

Deborah M. Muoio, Email: Debbie.muoio@duke.edu

Monica J. Hubal, mhubal@email.gwu.edu

William E. Kraus, Email: william.kraus@dm.duke.edu

References

- 1.Lee J, Dunlop D, Ehrlich-Jones L, Semanik P, Song J, Manheim L, Chang RW. Public health impact of risk factors for physical inactivity in adults with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012;64:488–493. doi: 10.1002/acr.21582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kotler DP. Cachexia. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133:622–634. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-8-200010170-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glass DJ. Skeletal muscle hypertrophy and atrophy signaling pathways. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2005;37:1974–1984. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2005.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, McShane DJ, Fries JF, Cooper NS, Healey LA, Kaplan SR, Liang MH, Luthra HS, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:315–324. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.AbouAssi H, Tune KN, Gilmore B, Bateman LA, McDaniel G, Muehlbauer M, Huebner JL, Hoenig HM, Kraus VB, St Clair EW, et al. Adipose depots, not disease-related factors, account for skeletal muscle insulin sensitivity in established and treated rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2014;41:1974–1979. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.140224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rigler SK, Studenski S, Wallace D, Reker DM, Duncan PW. Co-morbidity adjustment for functional outcomes in community-dwelling older adults. Clin Rehabil. 2002;16:420–428. doi: 10.1191/0269215502cr515oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruce B, Fries JF. The Stanford health assessment questionnaire: dimensions and practical applications. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:20. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prevoo ML, van 't Hof MA, Kuper HH, van Leeuwen MA, van de Putte LB, van Riel PL. Modified disease activity scores that include twenty-eight-joint counts. Development and validation in a prospective longitudinal study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:44–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Bartlett DB, Connelly MA, AbouAssi H, Bateman LA, Tune KN, Huebner JL, Kraus VB, Winegar DA, Otvos JD, Kraus WE, Huffman KM. A novel inflammatory biomarker, GlycA, associates with disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis and cardio-metabolic risk in BMI-matched controls. Arthritis Res Ther. 2016;18:86. doi: 10.1186/s13075-016-0982-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bergman RN, Ider YZ, Bowden CR, Cobelli C. Quantitative estimation of insulin sensitivity. Am J Physiol. 1979;236:E667–E677. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1979.236.6.E667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huffman KM, Pieper CF, Hall KS, St Clair EW, Kraus WE. Self-efficacy for exercise, more than disease-related factors, is associated with objectively assessed exercise time and sedentary behaviour in rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 2015;44:106–110. doi: 10.3109/03009742.2014.931456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bergstrom J. Percutaneous needle biopsy of skeletal muscle in physiological and clinical research. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1975;35:609–616. doi: 10.3109/00365517509095787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.An J, Muoio DM, Shiota M, Fujimoto Y, Cline GW, Shulman GI, Koves TR, Stevens R, Millington D, Newgard CB. Hepatic expression of malonyl-CoA decarboxylase reverses muscle, liver and whole-animal insulin resistance. Nat Med. 2004;10:268–274. doi: 10.1038/nm995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu JY, Kao HJ, Li SC, Stevens R, Hillman S, Millington D, Chen YT. ENU mutagenesis identifies mice with mitochondrial branched-chain aminotransferase deficiency resembling human maple syrup urine disease. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:434–440. doi: 10.1172/JCI19574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jensen MV, Joseph JW, Ilkayeva O, Burgess S, Lu D, Ronnebaum SM, Odegaard M, Becker TC, Sherry AD, Newgard CB. Compensatory responses to pyruvate carboxylase suppression in islet beta-cells. Preservation of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:22342–22351. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604350200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kramer A, Green J, Pollard Jr J, Tugendreich S. Causal analysis approaches in Ingenuity Pathway Analysis. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:523–30. 510.1093/bioinformatics/btt1703. Epub 2013 Dec 1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Cubillos-Zapata C, Hernandez-Jimenez E, Toledano V, Esteban-Burgos L, Fernandez-Ruiz I, Gomez-Pina V, Del Fresno C, Siliceo M, Prieto-Chinchina P, Perez de Diego R, et al. NFkappaB2/p100 is a key factor for endotoxin tolerance in human monocytes: a demonstration using primary human monocytes from patients with sepsis. J Immunol. 2014;193:4195–4202. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Geyer BC, Ben Ari S, Barbash S, Kilbourne J, Mor TS, Soreq H. Nicotinic stimulation induces Tristetraprolin over-production and attenuates inflammation in muscle. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1823:368–378. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carballo E, Lai WS, Blackshear PJ. Feedback inhibition of macrophage tumor necrosis factor-alpha production by tristetraprolin. Science. 1998;281:1001–1005. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5379.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hausburg MA, Doles JD, Clement SL, Cadwallader AB, Hall MN, Blackshear PJ, Lykke-Andersen J, Olwin BB. Post-transcriptional regulation of satellite cell quiescence by TTP-mediated mRNA decay. Elife. 2015;4:e03390. doi: 10.7554/eLife.03390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu TM, Lee EH, Lim B, Shyh-Chang N. Concise review: balancing stem cell self-renewal and differentiation with PLZF. Stem Cells. 2016;34:277–287. doi: 10.1002/stem.2270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kranc KR, Schepers H, Rodrigues NP, Bamforth S, Villadsen E, Ferry H, Bouriez-Jones T, Sigvardsson M, Bhattacharya S, Jacobsen SE, Enver T. Cited2 is an essential regulator of adult hematopoietic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:659–665. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bhattacharya S, Michels CL, Leung MK, Arany ZP, Kung AL, Livingston DM. Functional role of p35srj, a novel p300/CBP binding protein, during transactivation by HIF-1. Genes Dev. 1999;13:64–75. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.1.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lamon S, Wallace MA, Russell AP. The STARS signaling pathway: a key regulator of skeletal muscle function. Pflugers Arch. 2014;466:1659–1671. doi: 10.1007/s00424-014-1475-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rybkin OM, II, Copeland V, Czubryt MP, Shelton JM, van Rooij E, Richardson JA, Hill JA, De Windt LJ, Bassel-Duby R, et al. Calcineurin is necessary for the maintenance but not embryonic development of slow muscle fibers. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:6629–6638. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.15.6629-6638.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maeda T, Chapman DL, Stewart AF. Mammalian vestigial-like 2, a cofactor of TEF-1 and MEF2 transcription factors that promotes skeletal muscle differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:48889–98. Epub 42002 Oct 48889. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Bonnet A, Dai F, Brand-Saberi B, Duprez D. Vestigial-like 2 acts downstream of MyoD activation and is associated with skeletal muscle differentiation in chick myogenesis. Mech Dev. 2010;127:120–136. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang Y, Creer A, Jemiolo B, Trappe S. Time course of myogenic and metabolic gene expression in response to acute exercise in human skeletal muscle. 1985) 2005; 98:1745-1752. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Ma Z, Sun X, Xu D, Xiong Y, Zuo B. MicroRNA, miR-374b, directly targets Myf6 and negatively regulates C2C12 myoblasts differentiation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;467:670–675. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.10.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hawke TJ, Kanatous SB, Martin CM, Goetsch SC, Garry DJ. Rad is temporally regulated within myogenic progenitor cells during skeletal muscle regeneration. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2006;290:C379–C387. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00270.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wehling-Henricks M, Jordan MC, Gotoh T, Grody WW, Roos KP, Tidball JG. Arginine metabolism by macrophages promotes cardiac and muscle fibrosis in mdx muscular dystrophy. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10763. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spang N, Feldmann A, Huesmann H, Bekbulat F, Schmitt V, Hiebel C, Koziollek-Drechsler I, Clement AM, Moosmann B, Jung J, et al. RAB3GAP1 and RAB3GAP2 modulate basal and rapamycin-induced autophagy. Autophagy. 2014;10:2297–2309. doi: 10.4161/15548627.2014.994359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Su J, Ekman C, Oskolkov N, Lahti L, Strom K, Brazma A, Groop L, Rung J, Hansson O. A novel atlas of gene expression in human skeletal muscle reveals molecular changes associated with aging. Skelet Muscle. 2015;5:35. doi: 10.1186/s13395-015-0059-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pandey SN, Cabotage J, Shi R, Dixit M, Sutherland M, Liu J, Muger S, Harper SQ, Nagaraju K, Chen YW. Conditional over-expression of PITX1 causes skeletal muscle dystrophy in mice. Biol Open. 2012;1:629–639. doi: 10.1242/bio.20121305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Merico D, Roifman M, Braunschweig U, Yuen RK, Alexandrova R, Bates A, Reid B, Nalpathamkalam T, Wang Z, Thiruvahindrapuram B, et al. Compound heterozygous mutations in the noncoding RNU4ATAC cause Roifman Syndrome by disrupting minor intron splicing. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8718. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nagy R, Wang H, Albrecht B, Wieczorek D, Gillessen-Kaesbach G, Haan E, Meinecke P, de la Chapelle A, Westman JA. Microcephalic osteodysplastic primordial dwarfism type I with biallelic mutations in the RNU4ATAC gene. Clin Genet. 2012;82:140–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2011.01756.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tobimatsu K, Noguchi T, Hosooka T, Sakai M, Inagaki K, Matsuki Y, Hiramatsu R, Kasuga M. Overexpression of the transcriptional coregulator Cited2 protects against glucocorticoid-induced atrophy of C2C12 myotubes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;378:399–403. 310.1016/j.bbrc.2008.1011.1062. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Hountondji C, Bulygin K, Crechet JB, Woisard A, Tuffery P, Nakayama J, Frolova L, Nierhaus KH, Karpova G, Baouz S. The CCA-end of P-tRNA contacts both the human RPL36AL and the A-site bound translation termination factor eRF1 at the peptidyl transferase center of the human 80s ribosome. Open Biochem J. 2014;8:52–67. doi: 10.2174/1874091X01408010052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tillmann H, Eschrich K. Isolation and characterization of an allelic cDNA for human muscle fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase. Gene. 1998;212:295–304. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(98)00181-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rakus D, Maciaszczyk E, Wawrzycka D, Ulaszewski S, Eschrich K, Dzugaj A. The origin of the high sensitivity of muscle fructose 1,6-bisphosphatase towards AMP. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:5577–5581. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pirog M, Gizak A, Rakus D. Changes in quaternary structure of muscle fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase regulate affinity of the enzyme to mitochondria. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2014;48:55–59. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2013.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Herrer I, Rosello-Lleti E, Rivera M, Molina-Navarro MM, Tarazon E, Ortega A, Martinez-Dolz L, Trivino JC, Lago F, Gonzalez-Juanatey JR, et al. RNA-sequencing analysis reveals new alterations in cardiomyocyte cytoskeletal genes in patients with heart failure. Lab Invest. 2014;94:645–653. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2014.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Qiao S, Dennis M, Song X, Vadysirisack DD, Salunke D, Nash Z, Yang Z, Liesa M, Yoshioka J, Matsuzawa S, et al. A REDD1/TXNIP pro-oxidant complex regulates ATG4B activity to control stress-induced autophagy and sustain exercise capacity. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7014. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tsukahara M, Suemori H, Noguchi S, Ji ZS, Tsunoo H. Novel nucleolar protein, midnolin, is expressed in the mesencephalon during mouse development. Gene. 2000;254:45–55. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(00)00259-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hofmeister-Brix A, Kollmann K, Langer S, Schultz J, Lenzen S, Baltrusch S. Identification of the ubiquitin-like domain of midnolin as a new glucokinase interaction partner. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:35824–35839. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.526632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stuart CA, Yin D, Howell ME, Dykes RJ, Laffan JJ, Ferrando AA. Hexose transporter mRNAs for GLUT4, GLUT5, and GLUT12 predominate in human muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2006;291:E1067–E1073. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00250.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Karunakaran D, Thrush AB, Nguyen MA, Richards L, Geoffrion M, Singaravelu R, Ramphos E, Shangari P, Ouimet M, Pezacki JP, et al. Macrophage mitochondrial energy status regulates cholesterol efflux and is enhanced by anti-miR33 in atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2015;117:266–278. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.305624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Anunciado-Koza RP, Zhang J, Ukropec J, Bajpeyi S, Koza RA, Rogers RC, Cefalu WT, Mynatt RL, Kozak LP. Inactivation of the mitochondrial carrier SLC25A25 (ATP-Mg2+/Pi transporter) reduces physical endurance and metabolic efficiency in mice. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:11659–11671. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.203000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Plaisier CL, Bennett BJ, He A, Guan B, Lusis AJ, Reue K, Vergnes L. Zbtb16 has a role in brown adipocyte bioenergetics. Nutr Diabetes. 2012;2:e46. doi: 10.1038/nutd.2012.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gordon EA, Whisenant TC, Zeller M, Kaake RM, Gordon WM, Krotee P, Patel V, Huang L, Baldi P, Bardwell L. Combining docking site and phosphosite predictions to find new substrates: identification of smoothelin-like-2 (SMTNL2) as a c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) substrate. Cell Signal. 2013;25:2518–2529. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2013.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.