Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

To examine changes in the prevalence of 15 HIV/AIDS sex and drug risk behaviors in delinquent youth during the 14 years after they leave detention, focusing on sex and racial/ethnic differences.

METHODS:

The Northwestern Juvenile Project, a prospective longitudinal study of 1829 youth randomly sampled from detention in Chicago, Illinois, recruited between 1995 and 1998 and reinterviewed up to 11 times. Independent interviewers assessed HIV/AIDS risk behaviors using the National Institutes on Drug Abuse Risk Behavior Assessment.

RESULTS:

Fourteen years after detention (median age, 30 years), one-quarter of males and one-tenth of females had >1 sexual partner in the past 3 months. One-tenth of participants reported recent unprotected vaginal sex with a high-risk partner. There were many sex and racial/ethnic differences. For example, African American males had 4.67 times the odds of having >1 partner than African American females (95% confidence interval [CI], 3.22–6.76). Over time, compared with non-Hispanic white males, African American males had 2.56 times the odds (95% CI, 1.97–3.33) and Hispanic males had 1.63 times the odds (95% CI, 1.24–2.12) of having multiple partners, even after adjusting for incarceration and age. Non-Hispanic white females were more likely to have multiple partners than racial/ethnic minority females.

CONCLUSIONS:

Although rates decrease over time, prevalence of sex risk behaviors are much higher than the general population. Among males, racial/ethnic minorities were at particular risk. The challenge for pediatric health is to address how disproportionate confinement of racial/ethnic minority youth contributes to disparities in the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

What’s Known on This Subject:

Detained youth initiate HIV/AIDS risk behaviors at younger ages and report more risk behaviors than those in the general population. Yet, we know little about the prevalence and patterns of risk behaviors after youth leave detention and age into adulthood.

What This Study Adds:

Although rates decrease over time, sex risk behaviors remain prevalent among detained youth as they age, especially among racial/ethnic minority males. The pediatric community must address how disproportionate confinement of racial/ethnic minority youth contributes to HIV/AIDS health disparities.

HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) disproportionately affect young people. Although persons aged 13 to 29 years comprise 23% of the US population,1 they accounted for 39.9% of all new HIV infections in 2014.2 Moreover, those aged 25 to 29 years are the only age group to have an increase in the number of new infections over the past 4 years.2

Delinquent youth are an especially high-risk population, reporting more risk behaviors and initiating them at younger ages than youth in the general population.3–15 The Northwestern Juvenile Project found that 95% of newly detained youth reported engaging in ≥3 risk behaviors.15 HIV/AIDS risk behaviors were prevalent, irrespective of sex, race/ethnicity, or age.15

Despite their importance, we know little about the prevalence and patterns of risk behaviors after youth leave detention. We searched the literature for longitudinal studies of delinquent youth, defined as a follow-up of ≥2 years, finding only 3 studies.10,16,17 Although all found that HIV/AIDS risk behaviors persisted with age, the studies examined only a few risk behaviors or followed participants only through adolescence.10,16,17

This omission is critical. Racial/ethnic minorities, especially African Americans, are overrepresented in the juvenile justice system18,19 and suffer disproportionately from HIV/AIDS.2,20 Although African American youth comprise only 15% of the general population aged 13 to 29 years,1 they comprised 39% of incarcerated youth and young adults21,22 and 51.7% of new HIV infections in that age group in 2014.2 Moreover, studies of adult inmates indicated that delinquent youth are at great risk for contracting HIV/AIDS as they age: HIV/AIDS risk behaviors are prevalent in adult male and female inmates,23,24 and the prevalence of confirmed AIDS cases among adult prisoners is 2.4 times higher than among adults in the general US population.25

The Northwestern Juvenile Project, the first large-scale longitudinal study of HIV/AIDS risk in delinquent youth during adulthood, has methodological strengths that address the limitations of previous investigations: (1) a comprehensive measure of 15 HIV/AIDS risk behaviors; (2) a lengthy follow-up period (14 years) to a median age of 30 years; and (3) a large sample, sufficiently diverse to examine females, a group increasingly involved in the justice system,22,26,27 and disparities among racial/ethnic minorities (African Americans and Hispanics). We examine changes in the prevalence of sex and drug risk behaviors during the 14 years after youth leave detention, focusing on sex and racial/ethnic differences.

Methods

The most relevant information on our methods is summarized in this section. Additional information, available in the Supplemental Materials, was published elsewhere.15,28

Sample and Procedures

We recruited a stratified random sample of 1829 youth at intake to the Cook County Juvenile Temporary Detention Center (CCJTDC) in Chicago, Illinois, between November 20, 1995 and June 14, 1998. The CCJTDC is used for pretrial detention and for offenders sentenced for <30 days. To ensure adequate representation of key subgroups, we stratified our sample by sex, race/ethnicity (African American, non-Hispanic white, Hispanic, or other), age (10–13 years or 14–18 years), and legal status (processed in juvenile or adult court). Face-to-face structured interviews were conducted at the detention center in a private area, most within 2 days of intake. We followed the 1829 participants for the next 14 years.

At baseline, we received funding to administer the HIV/AIDS measure to the last 800 participants enrolled (460 boys and 340 girls). The entire sample was reinterviewed 3, 5, 6, 8, 12, and 14 years after the baseline interview (referred to hereafter as “after detention”). In addition, a random subsample of 997 youth (600 boys and 397 girls) were reinterviewed 3.5 and 4 years after detention. The last 800 participants enrolled at baseline (460 boys and 340 girls) were reinterviewed 10, 11, and 13 years after detention (our design was determined, in part, by the funding that was available). Participants were interviewed whether they lived in the community or in correctional facilities; 80% of participants had an interview at year 14 (105 had died, 81 refused to participate, and 180 could not be located in time for the interview).

Procedures to Obtain Assent and Consent at Baseline and Follow-up

For all interviews, participants signed either an assent form (<18 years old) or a consent form (≥18 years old). The Institutional Review Boards of Northwestern University and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention approved all study procedures and waived parental consent for persons <18 years, consistent with federal regulations regarding research with minimal risk.29

Measures and Variables

HIV/AIDS risk behaviors were assessed using the National Institute on Drug Abuse Risk Behavior Assessment, a reliable and valid measure of drug and sex risk behaviors.30–32 We supplemented the Risk Behavior Assessment with items from Yale’s AIDS Risk Inventory.33 All HIV/AIDS risk variables are binary and assessed via self-report.

We assessed the following variables: multiple partners (>1 or >3); unprotected vaginal sex; unprotected anal sex (all assessed for the 3 months before the interview); sex while drunk or high; traded sex for drugs; and shared needles or equipment for injection drug use or tattooing (assessed for the 2 years before the interview).

As youth age into young adulthood, they are more likely to have an exclusive sexual relationship with a primary partner and thus stop using protection. Therefore, beginning with the 10-year follow-up interview, we added the following behaviors (assessed 3 months before the interview): unprotected vaginal sex with a high-risk partner; unprotected anal sex with a high-risk partner; unprotected sex while drunk or high; and sex while drunk or high with a high-risk partner. As in previous studies,34,35 a “high-risk partner” refers to someone whom the participant identified as having worked as a prostitute, having HIV or AIDS, having injected drugs, or whose sexual history the participant did not know well (unless specified, risk behaviors may have been protected or unprotected).

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were conducted by using commercial software (Stata version 12, Stata Corp, College Station, TX) with its survey routines. To generate prevalence estimates and inferential statistics that reflect CCJTDC’s population, each participant was assigned a sampling weight augmented with a nonresponse adjustment to account for missing data.

Because some participants were interviewed more often than others, we summarized prevalence at 6 time points: the baseline interview and follow-up interviews at ∼5, 8, 10, 12, and 14 years after detention. Because many behaviors are restricted in correctional settings, for each follow-up, we omitted from analyses participants who had been incarcerated during the entire recall period. Supplemental Table 1 summarizes demographic characteristics and retention rates: 1789 participants provided data at ≥1 time points. Analyses assessing the effect of attrition on generalizability are reported in the Supplemental Materials. Race/ethnicity (African American, Hispanic, non-Hispanic white, and other) was self-identified.

Changes in Prevalence as Youth Age

We used all available interviews, an average of 6.4 interviews per person (range, 1–12 interviews per person). We used generalized estimating equations (GEEs) to fit marginal models examining: (1) differences in the prevalence of risk behaviors by sex and race/ethnicity over time and (2) changes in risk behaviors as youth aged. Unless otherwise noted, odds ratios (ORs) indicate sex and racial/ethnic differences over time.

All GEE models included covariates for sex, race/ethnicity (African American, Hispanic, or non-Hispanic white), aging (time since detention), age at detention (10–18 years), and legal status at detention. Four participants who identified as “other” race/ethnicity were excluded. We modeled time since detention using restricted cubic splines with 2 interior knots. When main effects were significant, we estimated models with the corresponding interaction terms. Only statistically significant interaction terms were included in final models. For models with significant interactions between sex and aging, we report model-based ORs for sex differences at 5, 8, 12, and 14 years after detention. Because disproportionate incarceration may confound racial/ethnic differences in HIV/AIDS risk behaviors, all models included the length of time incarcerated (days) during the recall period and an indicator for living entirely in the community (yes/no). All GEE models were estimated with sampling weights to account for study design.

Results

Figures 1, 2 and 3 illustrate sex and racial/ethnic differences over time for multiple partners, unprotected sex, and sex while drunk or high, respectively. Supplemental Tables 2–4 provide the specific prevalence estimates shown in the figures. Supplemental Table 5 shows the percentage of participants who reported risk behaviors in half or more of their interviews. Supplemental Tables 6–8 show adjusted ORs and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) examining (1) changes in prevalence as youth age and (2) sex and racial/ethnic differences in prevalence over time. We discuss significant findings by category of HIV/AIDS risk behavior.

FIGURE 1.

Prevalence of multiple partners in delinquent youth from detention (baseline) through 14 years: sex and racial/ethnic differences.

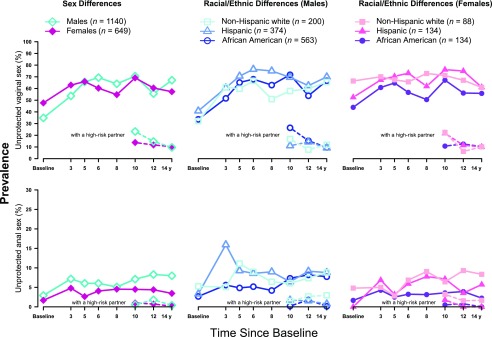

FIGURE 2.

Prevalence of unprotected sex in delinquent youth from detention (baseline) through 14 years: sex and racial/ethnic differences. The y-axis (prevalence) scale differs between unprotected vaginal sex and unprotected anal sex.

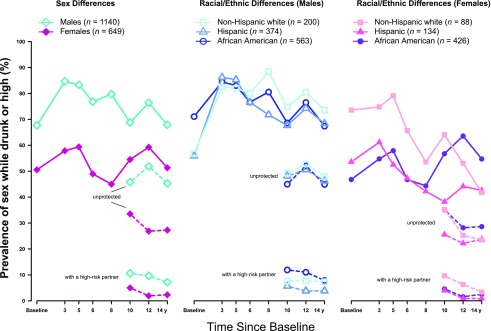

FIGURE 3.

Prevalence of sex while drunk or high in delinquent youth from detention (baseline) through 14 years: sex and racial/ethnic differences. Sex while drunk or high is assessed for the past 2 years at each time point. Sex while drunk or high, either unprotected or with a high-risk partner, are assessed for the past 3 months at each time point.

Multiple Partners

Prevalence (>1 or >3 partners) decreased as participants aged (Fig 1), although prevalence remained notable: 14 years after detention, nearly 1 in 10 females and more than one-quarter of males reported having >1 partner in the past 3 months (Supplemental Table 2). Among males, 52% reported multiple partners, with 18% reporting >3 partners, at half or more of their interviews. Among females, only 13% reported multiple partners at half or more of their interviews (Supplemental Table 5). The rate of the decline in multiple partners (>1) depended on sex and race/ethnicity (Supplemental Tables 3 and 4).

Sex Differences

Among minorities, males were more likely to have multiple partners (>1 or >3) than females. For example, 14 years after detention, African American males had 4.67 times the odds of having >1 partner than African American females (95% CI, 3.22–6.76); Hispanic males had 3.43 times the odds compared with Hispanic females (95% CI, 2.18–5.40) (Supplemental Table 6).

Racial/Ethnic Differences

Among males as they aged, African American youth had the highest prevalence of multiple partners (>1 or >3), followed by Hispanic, then non-Hispanic white youth (Supplemental Table 6). Minority females had a lower prevalence of multiple partners (>1) compared with non-Hispanic white females (Supplemental Table 6).

Unprotected Vaginal Sex

Figure 2 (top panel) illustrates sex and racial/ethnic differences in unprotected vaginal sex and unprotected vaginal sex with a high-risk partner (see also Supplemental Tables 2–4). Unprotected vaginal sex was common: 14 years after detention, more than two-thirds of males and more than half of females reported this behavior. Unprotected vaginal sex with a high-risk partner was less common, reported by about 1 in 10 males and females 14 years after detention. Overall, 17% of males and 8% of females reported this behavior at more than half of their follow-up interviews (Supplemental Table 5). The prevalence of unprotected vaginal sex generally increased over time, but the rate of increase depended on sex and race/ethnicity.

Sex Differences

At detention, males were less likely to have unprotected vaginal sex than females, regardless of race/ethnicity (Supplemental Table 6). However, among African American participants, males were more likely than females to report unprotected vaginal sex as they aged.

Racial/Ethnic Differences

Unprotected vaginal sex was more common among Hispanic males compared with non-Hispanic white and African American males (Supplemental Table 6). Unprotected vaginal sex was more common among Hispanic and non-Hispanic white females compared with African American females (Supplemental Table 6).

Unprotected Anal Sex

Anal sex risk behaviors (unprotected anal sex and unprotected anal sex with a high-risk partner) were among the least prevalent sex risk behaviors, and prevalence remained stable over time (Fig 2, bottom panel). Fourteen years after detention, prevalence of unprotected anal sex was 8% among males and 3.5% among females; <1% of participants reported unprotected anal sex with a high-risk partner.

Compared with females, males had 1.77 times the odds of having unprotected anal sex (95% CI, 1.30–2.40).

Sex While Drunk or High

Figure 3 illustrates sex and racial/ethnic differences. Having sex while drunk or high was among the most common risk behaviors, as was the riskier behavior of having unprotected sex while drunk or high: 14 years after detention, almost half of males and more than one-quarter of females reported having unprotected sex while drunk or high (Supplemental Table 2). Having sex while drunk or high with a high-risk partner was less prevalent: 7.2% among males and 2.3% among females. Overall, 8% of males and 3% of females reported this behavior at more than half of their follow-up interviews (Supplemental Table 5).

Sex Differences

Having sex while drunk or high was more prevalent among males than females; the magnitude of the difference depended on race/ethnicity and time since detention (Supplemental Table 8). Males also had higher prevalence of having unprotected sex while drunk or high than females (Supplemental Table 7).

Racial/Ethnic Differences

Non-Hispanic white females had 1.52 times greater odds of having sex while drunk or high than African American females (95% CI, 1.07–2.16) and 1.60 times the odds than Hispanic females (95% CI, 1.08–2.37).

Trading Sex and Drugs

Trading sex and drugs was infrequent: at most follow-ups, <1% of participants reported trading sex and drugs during the past 2 years (Supplemental Table 2). Prevalence was highest 5 years after detention (about 7% among both males and females). As they agreed, African American youth had 2.41 times greater odds of trading sex and drugs compared with Hispanic youth (95% CI, 1.39–4.16) (Supplemental Table 8).

Sharing Needles

Few participants reported sharing needles. Fourteen years after detention, no males and <1% of females reported sharing needles. As they agreed, Hispanic youth were more likely to have shared needles than African American youth (Supplemental Table 8).

Multiple Risk Behaviors

Because engaging in >1 risk behavior may make youth more vulnerable to HIV/AIDS, we also examined the prevalence of multiple behaviors during the past 3 months. Figure 4 illustrates sex and racial/ethnic differences in the overlap of 3 types of risk behaviors: multiple partners, unprotected sex with a high-risk partner, and risky sex while drunk or high (unprotected or with a high-risk partner). Prevalence estimates are for the 14-year interview, with risk behaviors assessed for the past 3 months.

FIGURE 4.

Prevalence of specific and co-occurring HIV/AIDS risk behaviors in delinquent youth 14 years after detention: sex and racial/ethnic differences. a Does not sum due to rounding error.

There was substantial overlap among the 3 types of behaviors for males: about 19% of African American and Hispanic males and 14% of non-Hispanic white males engaged in ≥2 types of risky behavior during the past 3 months.

In contrast, ∼8% of African American, 5% of Hispanic, and 12% of non-Hispanic white females engaged in at least 2 of the behaviors. About 7% of non-Hispanic white females engaged in all 3 behaviors, compared with 1% of African American females and no Hispanic females.

Discussion

In the general population, the prevalence of HIV/AIDS risk behaviors peaks in the early 20s and gradually declines over time,36 a pattern also found in our sample. Yet, although the prevalence of most risk behaviors declined with age, delinquent youth continue to be at great risk for HIV and other STIs, particularly for behaviors associated with heterosexual contact. Fourteen years after detention, when participants were a median age of 30 years, one-quarter of males and one-tenth of females had >1 sexual partner in the past 3 months. In contrast, in a national sample of young adults ages 15 to 44 years, 18% of males and 14% of females reported having >1 partner in the past year.37 Moreover, one-tenth of males and females in our sample reported recent unprotected vaginal sex with a high-risk partner. Unprotected vaginal sex poses an even higher risk for females than for males.38 Heterosexual sex is now the most common route of transmission for HIV/AIDS and STIs in the United States for females overall (87% of new infections2) and for females in correctional facilities (64% of new infections).2,20

Risk behaviors associated with alcohol and noninjection drug use were common as youth aged. Fourteen years after detention, nearly half of males and more than one-quarter of females reported having unprotected sex while drunk or high in the past 3 months. Substance use can increase the chance for risky sexual behaviors by compromising judgment, reducing condom use, and compromising the correct use of condoms.39–41

Among males, we found many racial/ethnic differences in the prevalence of risk behaviors. Even after adjusting for incarceration and age, African American males had the highest prevalence of multiple partners compared with Hispanic and non-Hispanic white males. This disparity mirrors trends among males in the general population, where African American adolescents42 and adults36 are significantly more likely to have multiple sex partners than other racial/ethnic groups. We also found that as they aged, Hispanic males were more likely than non-Hispanic white males to have multiple partners and more likely than males of other racial/ethnic groups to have unprotected vaginal sex. Our findings on Hispanic males are of particular concern. Hispanic people comprise ∼17% of the US population, but accounted for 22.7% of new HIV infections among persons aged 13 to 29 years in 2014.2 Moreover, among Hispanic people, males comprised 85% of new HIV infections in 2013.43

Among females, however, non-Hispanic white youth were more likely than minority youth to have multiple partners and to have sex while drunk or high, as they agreed. This may be because, in our sample, substance use disorders, a risk factor for many behaviors, are more common in non-Hispanic white females than in racial/ethnic minority females.44 Of note, as in the general population,45 African American females in our sample had a lower prevalence of many sex risk behaviors than non-Hispanic white females. However, African American females in the general population continue to be disproportionately affected by HIV, likely because of a greater risk of encountering an infected partner.45

Limitations

It was not feasible to study >1 jurisdiction, and findings may be generalizable only to delinquent youth in urban detention centers with similar demographic compositions. Although retention was high, findings on risk behaviors assessed at follow-up may have been affected by missing data. Some behaviors may confer more risk for contracting STIs with a secondary risk for contracting HIV.46 We did not collect data on some risk behaviors until participants were young adults. Data are subject to the limitations of self-report. Males who have sex with males are stigmatized in African American and Hispanic communities.47,48 Hence, the actual prevalence of some behaviors may be higher than reported. Finally, we did not examine how marital status, living arrangements, or other variables affect risk behaviors.

Future Research and Implications for Pediatric Health

Incorporate HIV/AIDS education, counseling, and support into substance abuse treatment of at-risk youth and young adults. The importance of providing HIV/AIDS preventive interventions in correctional settings cannot be overstated.49,50 However, because juvenile and adult detainees are usually released in a matter of days,51 preventive interventions must also be provided in communities after release. One strategy is to incorporate evidence-based HIV preventive interventions52,53 into substance abuse services. Because substance use disorders are prevalent among juvenile detainees14,54 and persist as they age,28 this approach would reach many youth at risk for HIV. However, we must improve service availability; currently, only 1 in 4 substance abuse treatment facilities offer HIV testing, and just over half (58%) provide HIV/AIDS education, counseling, or support services.55

Incorporate HIV/AIDS prevention into routine pediatric care. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that, with the adolescent’s consent, pediatricians should conduct HIV and STI tests annually for high-risk youth.56 Pediatricians should also conduct risk-reduction counseling in an atmosphere of tolerance.56,57 Counseling should include the assessment of sexual and substance use history, education about risks, and support for safe behaviors.57 Strength-based interventions58 and motivational interviewing techniques59 could increase the adolescent’s intrinsic motivation to change.

Examine how incarceration affects the development and persistence of HIV/AIDS risk behaviors in high-risk youth. Certainly, many delinquent youth have engaged in HIV/AIDS risk behaviors before they were detained.60,61 Yet, the experience of incarceration disrupts normal development, leading to additional risks. Studies of high-risk populations in the community (eg, homeless adults and persons involved in sex parties) suggest that the experience of incarceration21 may be a key predictive variable of subsequent HIV/AIDS risk behaviors.62–72 Because drugs, alcohol, and sex partners are restricted in correctional settings, released juveniles may engage in risky behaviors to compensate for the deprivations experienced during incarceration.73–75 Moreover, long correctional stays may disrupt social networks, leading to more sex partners after release.68,76,77 Yet, little is known about how incarceration affects HIV/AIDS risk behaviors in delinquent youth after release.61,75,78 We suggest that prospective studies investigate the following variables: the number of incarcerations, age at time of incarceration, length of incarcerations, and experiences in “community corrections” (parole, probation, and community supervision). This strategy would generate necessary information on how disproportionate confinement of racial/ethnic minority youth affects health disparities in HIV/AIDS.

Conclusions

Although the United States has the highest incarceration rate among developed nations (698 inmates per 100 000 residents versus 106 in Canada and 148 in England),79 surprisingly few studies examine health outcomes of delinquent youth after they leave detention. We know the least about the populations that are at greatest risk for HIV/AIDS as they age. The challenge for pediatric health is to address how disproportionate confinement of racial/ethnic minority youth in the United States leads to health disparities in the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

Acknowledgments

Zaoli Zhang, MS, prepared the data and generated modified diagnostic algorithms. Jessica Jakubowski, PhD, provided assistance preparing data. Frank Palella, MD, Ronald Stall, PhD, Michael W. Plankey, PhD, Celia Fisher, PhD, and the anonymous reviewers provided invaluable advice on the project. We thank our participants for their time and willingness to participate; our talented and intrepid field staff; the Circuit Court of Cook County including the Cook County Juvenile Temporary Detention Center, the Juvenile Justice and Child Protection Department, the Juvenile Probation and Court Services Department, the Social Service Department, Adult Probation, and Forensic Clinical Services; the Cook County Department of Corrections; the Illinois Department of Juvenile Justice; and the Illinois Department of Corrections for their cooperation.

Glossary

- CCJTDC

Cook County Juvenile Temporary Detention Center

- CI

confidence interval

- GEE

generalized estimating equations

- OR

odds ratio

- STI

sexually transmitted infection

Footnotes

Drs Abram and Teplin conceptualized and designed the study, supervised the study, contributed to drafting and revising the article for important intellectual content, and interpreted the analysis and results; Ms Stokes conceptualized and designed the study, contributed to drafting and revising the article for important intellectual content, conducted the statistical analysis, and interpreted the analysis and results; Dr Welty conceptualized and designed the study, supervised the study, contributed to drafting and revising the article for important intellectual content, conducted the statistical analysis, and interpreted the analysis and results; Mr Aaby contributed to drafting and revising the article for important intellectual content, conducted the statistical analysis, and interpreted the analysis and results; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: This work was supported by: The National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Institute on Drug Abuse grants R01DA019380, R01DA022953, and R01DA028763; the NIH National Institute of Mental Health grants R01MH54197 and R01MH59463 (Division of Services and Intervention Research and Center for Mental Health Research on AIDS); and Department of Justice grants 1999-JE-FX-1001, 2005-JL-FX-0288, and 2008-JF-FX-0068 from the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. Major funding was also provided by the NIH National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, the NIH Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (Center for Mental Health Services, Center for Substance Abuse Prevention, Center for Substance Abuse Treatment), the NIH Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (National Center for Injury Prevention and Control and National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention), the NIH Office of Research on Women's Health, the NIH Office of Rare Diseases, the Department of Labor, the Department of Housing and Urban Development, the William T. Grant Foundation, and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Additional funds were provided by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Open Society Institute, and the Chicago Community Trust. Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

COMPANION PAPERS: Companions to this article can be found online at www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2016-2624 and www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2016-3557.

References

- 1.US Census Bureau, Population Division Annual estimates of the resident population by single year of age and sex for the United States. April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2014. Available at: https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?src=bkmk. Accessed August 1, 2015

- 2.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Diagnoses of HIV infection in the United States and dependent areas, 2014. HIV Surveillance Report, 2014 Vol. 26. Available at: www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-report-us.pdf. Accessed September 22, 2015

- 3.Canterbury RJ, McGarvey EL, Sheldon-Keller AE, Waite D, Reams P, Koopman C. Prevalence of HIV-related risk behaviors and STDs among incarcerated adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 1995;17(3):173–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DiClemente RJ, Lanier MM, Horan PF, Lodico M. Comparison of AIDS knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors among incarcerated adolescents and a public school sample in San Francisco. Am J Public Health. 1991;81(5):628–630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gillmore MR, Morrison DM, Lowery C, Baker SA. Beliefs about condoms and their association with intentions to use condoms among youths in detention. J Adolesc Health. 1994;15(3):228–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Magura S, Kang SY, Shapiro JL. Outcomes of intensive AIDS education for male adolescent drug users in jail. J Adolesc Health. 1994;15(6):457–463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morris RE, Harrison EA, Knox GW, Tromanhauser E, Marquis DK, Watts LL. Health risk behavioral survey from 39 juvenile correctional facilities in the United States. J Adolesc Health. 1995;17(6):334–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morrison DM, Baker SA, Gillmore MR. Sexual risk behavior, knowledge, and condom use among adolescents in juvenile detention. J Youth Adolesc. 1994;23(2):271–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rolf J, Nanda J, Baldwin J, Chandra A, Thompson L. Substance misuse and HIV/AIDS risks among delinquents: a prevention challenge. Int J Addict. 1990-1991;25(4A):533–559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Romero EG, Teplin LA, McClelland GM, Abram KM, Welty LJ, Washburn JJ. A longitudinal study of the prevalence, development, and persistence of HIV/sexually transmitted infection risk behaviors in delinquent youth: implications for health care in the community. Pediatrics. 2007;119(5). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/119/5/e1126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Setzer JR, Scott AA, Balli J, et al. An integrated model for medical care, substance abuse treatment and AIDS prevention services to minority youth in a short-term detention facility. J Prison Jail Health. 1991;10(2):91–115 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shafer MA, Hilton JF, Ekstrand M, et al. Relationship between drug use and sexual behaviors and the occurrence of sexually transmitted diseases among high-risk male youth. Sex Transm Dis. 1993;20(6):307–313 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sickmund M, Wan Y. Census of Juveniles in Residential Placement Databook. Washington, DC: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Teplin LA, Abram KM, McClelland GM, Dulcan MK, Mericle AA. Psychiatric disorders in youth in juvenile detention. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(12):1133–1143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Teplin LA, Mericle AA, McClelland GM, Abram KM. HIV and AIDS risk behaviors in juvenile detainees: implications for public health policy. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(6):906–912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dembo R, Wothke W, Seeberger W, et al. Testing a model of the influence of family problem factors on high-risk youths’ troubled behavior: a three-wave longitudinal study. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2000;32(1):55–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Odgers CL, Robins SJ, Russell MA. Morbidity and mortality risk among the “forgotten few”: why are girls in the justice system in such poor health? Law Hum Behav. 2010;34(6):429–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carson AE, Sabol WJ; US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs Prisoners in 2011. Bureau of Justice Statistics Bulletin Available at: www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/p11.pdf. Accessed May 13, 2013

- 19.Hockenberry S; US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs Juveniles in residential placement, 2010. Juvenile Offenders and Victims: National Report Series Bulletin Available at: www.ojjdp.gov/pubs/241060.pdf. Accessed October 17, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barskey AE, Babu AS, Hernandez A, Espinoza L. Patterns and trends of newly diagnosed HIV infections among adults and adolescents in correctional and noncorrectional facilities, United States, 2008-2011. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(1):103–109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sabol WS, Minton TD, Harrison PM; US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs Prison and jail inmates at midyear 2006. Bureau of Justice Statistics Bulletin Available at: www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/pjim06.pdf. Accessed October 17, 2015

- 22.Sickmund M, Sladky TJ, Kang W, Puzzanchera C Easy access to the census of juveniles in residential placement: 1997-2013. Available at: www.ojjdp.gov/ojstatbb/ezacjrp/. Accessed August 8, 2014

- 23.Maruschak LM; US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs HIV in prisons, 2004. Bureau of Justice Statistics Bulletin Available at: www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/hivp04.pdf. Accessed August 20, 2015

- 24.McClelland GM, Teplin LA, Abram KM, Jacobs N. HIV and AIDS risk behaviors among female jail detainees: implications for public health policy. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(5):818–825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maruschak LM; US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs HIV in prisons, 2005. Bureau of Justice Statistics Bulletin Available at: www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/hivp05.pdf. Accessed July 1, 2014

- 26.Greenfeld LA, Snell T; US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs Women offenders. Bureau of Justice Statistics: Special Report Available at: www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/wo.pdf. Accessed August 16, 2015

- 27.Snyder HN; US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Juvenile arrests 2003. Juvenile Justice Bulletin Available at: www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/ojjdp/209735.pdf. Accessed August 16, 2015

- 28.Teplin LA, Welty LJ, Abram KM, Dulcan MK, Washburn JJ. Prevalence and persistence of psychiatric disorders in youth after detention: a prospective longitudinal study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(10):1031–1043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects: Notices and Rules. Part II. Federal Register. 1991:56(117):28002–28032 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dowling S, Johnson ME, Fisher DG. Reliability of drug users’ self-reported HIV risk behavior and validity of self-reported recent drug use. Assessment. 1994;1(4):382–392 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Needle R, Fisher D, Weatherby N, et al. Reliability of self-reported HIV risk behaviors of drug users. Psychol Addict Behav. 1995;9(4):242–250 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weatherby NL, Needle R, Cesari H. Validity of self-reported drug use among injection drug users and crack cocaine users recruited through street outreach. Eval Program Plann. 1994;17:347–355 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chawarski MC, Schottenfeld RS, Pakes J, Avants K. AIDS Risk Inventory (ARI): a structured interview for assessing risk of HIV infection in a population of drug abusers. In: Problems of Drug Dependence 1996: Proceedings of the 58th Annual Scientific Meeting, the College on Problems of Drug Dependence, Inc; June 20-27, 1996; San Juan, Puerto Rico. NIDA Research Monograph 174 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Donenberg GR, Emerson E, Bryant FB, Wilson H, Weber-Shifrin E. Understanding AIDS-risk behavior among adolescents in psychiatric care: links to psychopathology and peer relationships. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40(6):642–653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Donenberg GR, Schwartz RM, Emerson E, Wilson HW, Bryant FB, Coleman G. Applying a cognitive–behavioral model of HIV risk to youths in psychiatric care. AIDS Educ Prev. 2005;17(3):200–216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chandra A, Billioux VG, Copen CE, Sionean C. HIV risk-related behaviors in the United States household population aged 15-44 years: data from the National Survey of Family Growth, 2002 and 2006-2010. Natl Health Stat Rep. 2012;46:1–19 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mosher WD, Chandra A, Jones J. Sexual behavior and selected health measures: men and women 15-44 years of age, United States, 2002. Adv Data. 2005;362:1–55 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site HIV among women. Available at: www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/gender/women/. Accessed January 15, 2016

- 39.Cooper ML, Peirce RS, Huselid RF. Substance use and sexual risk taking among black adolescents and white adolescents. Health Psychol. 1994;13(3):251–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Malow RM, Dévieux JG, Rosenberg R, Samuels DM, Jean-Gilles MM. Alcohol use severity and HIV sexual risk among juvenile offenders. Subst Use Misuse. 2006;41(13):1769–1788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Patrick ME, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD, Terry-McElrath YM, Schulenberg JE. HIV/AIDS risk behaviors and substance use by young adults in the United States. Prev Sci. 2012;13(5):532–538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Santelli JS, Lindberg LD, Abma J, McNeely CS, Resnick M. Adolescent sexual behavior: estimates and trends from four nationally representative surveys. Fam Plann Perspect. 2000;32(4):156–165, 194 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Diagnoses of HIV infection in the United States and dependent areas, 2013. HIV Surveillance Report, 2013. Vol. 25. Available at: www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-report-2013-vol-25.pdf. Accessed August 13, 2015

- 44.Welty LJ, Harrison AJ, Abram KM, et al. Health disparities in drug- and alcohol-use disorders: a 12-year longitudinal study of youth after detention. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(5):872–880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hallfors DD, Iritani BJ, Miller WC, Bauer DJ. Sexual and drug behavior patterns and HIV and STD racial disparities: the need for new directions. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(1):125–132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mayo Clinic 2016. Diseases & conditions, Sexually transmitted diseases (STDs). Available at: www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/sexually-transmitted-diseases-stds/symptoms-causes/dxc-20180596. Accessed August 2, 2016

- 47.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention HIV/AIDS among African Americans. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/racialethnic/africanamericans/index.html. Accessed March 11, 2007

- 48.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention HIV/AIDS among Hispanics/Latinos. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/racialethnic/hispaniclatinos/index.html. Accessed February 15, 2008

- 49.Tolou-Shams M, Stewart A, Fasciano J, Brown LK. A review of HIV prevention interventions for juvenile offenders. J Pediatr Psychol. 2010;35(3):250–261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Underhill K, Dumont D, Operario D. HIV prevention for adults with criminal justice involvement: a systematic review of HIV risk-reduction interventions in incarceration and community settings. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(11):e27–e53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Snyder HN, Sickmund M; US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Juvenile offenders and victims: 2006 national report. Available at: www.ojjdp.gov/ojstatbb/nr2006/downloads/NR2006.pdf. Accessed January 24, 2013

- 52.Ziedenberg J. Models for change: building momentum for juvenile justice reform. A Justice Policy Institute report. Available at: www.justicepolicy.org/uploads/justicepolicy/documents/models_for_change.pdf. Accessed June 20, 2015

- 53.Butts JA, Roman J. Changing Systems: Outcomes from the RWJF Reclaiming Futures Initiative on Juvenile Justice and Substance Abuse. A Reclaiming Futures National Evaluation Report Portland, OR: Reclaiming Futures National Program Office, Portland State University;2007 [Google Scholar]

- 54.Abram KM, Teplin LA, McClelland GM, Dulcan MK. Comorbid psychiatric disorders in youth in juvenile detention. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(11):1097–1108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.US Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services (N-SSATS): 2012. Data on Substance Abuse Treatment Facilities BHSIS Series S-66, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4809. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 56.Emmanuel PJ, Martinez J; Committee on Pediatric AIDS . Adolescents and HIV infection: the pediatrician’s role in promoting routine testing. Pediatrics. 2011;128(5):1023–1029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.DiClemente RJ, Brown LK. Expanding the pediatrician’s role in HIV prevention for adolescents. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1994;33(4):235–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Herrick AL, Stall R, Goldhammer H, Egan JE, Mayer KH. Resilience as a research framework and as a cornerstone of prevention research for gay and bisexual men: theory and evidence. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(1):1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rubak S, Sandbaek A, Lauritzen T, Christensen B. Motivational interviewing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55(513):305–312 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Abiona TC, Balogun JA, Adefuye AS, Sloan PE. Pre-incarceration HIV risk behaviours of male and female inmates. Int J Prison Health. 2009;5(2):59–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Adams LM, Kendall S, Smith A, Quigley E, Stuewig JB, Tangney JP. HIV risk behaviors of male and female jail inmates prior to incarceration and one year post-release. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(8):2685–2694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kang S-Y, Deren S, Andia J, Colón HM, Robles R, Oliver-Velez D. HIV transmission behaviors in jail/prison among puerto rican drug injectors in New York and Puerto Rico. AIDS Behav. 2005;9(3):377–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Khan MR, Behrend L, Adimora AA, Weir SS, Tisdale C, Wohl DA. Dissolution of primary intimate relationships during incarceration and associations with post-release STI/HIV risk behavior in a Southeastern city. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38(1):43–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.López-Zetina J, Kerndt P, Ford W, Woerhle T, Weber M. Prevalence of HIV and hepatitis B and self-reported injection risk behavior during detention among street-recruited injection drug users in Los Angeles County, 1994-1996. Addiction. 2001;96(4):589–595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Youmans E, Burch J, Moran R, Smith L, Duffus WA. Disease progression and characteristics of HIV-infected women with and without a history of criminal justice involvement. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(8):2644–2653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.German D, Latkin CA. Social stability and HIV risk behavior: evaluating the role of accumulated vulnerability. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(1):168–178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hudson AL, Nyamathi A, Bhattacharya D, et al. Impact of prison status on HIV-related risk behaviors. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(2):340–346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Khan MR, Wohl DA, Weir SS, et al. Incarceration and risky sexual partnerships in a southern US city. J Urban Health. 2008;85(1):100–113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Epperson MW, Khan MR, El-Bassel N, Wu E, Gilbert L. A longitudinal study of incarceration and HIV risk among methadone maintained men and their primary female partners. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(2):347–355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bland SE, Mimiaga MJ, Reisner SL, et al. Sentencing risk: history of incarceration and HIV/STD transmission risk behaviours among Black men who have sex with men in Massachusetts. Cult Health Sex. 2012;14(3):329–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Swartzendruber A, Brown JL, Sales JM, Murray CC, DiClemente RJ. Sexually transmitted infections, sexual risk behavior, and intimate partner violence among African American adolescent females with a male sex partner recently released from incarceration. J Adolesc Health. 2012;51(2):156–163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Widman L, Noar SM, Golin CE, Willoughby JF, Crosby R. Incarceration and unstable housing interact to predict sexual risk behaviours among African American STD clinic patients. Int J STD AIDS. 2014;25(5):348–354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Khan MR, Epperson MW, Mateu-Gelabert P, Bolyard M, Sandoval M, Friedman SR. Incarceration, sex with an STI- or HIV-infected partner, and infection with an STI or HIV in Bushwick, Brooklyn, NY: a social network perspective. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(6):1110–1117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Seal DW, Margolis AD, Sosman J, Kacanek D, Binson D; Project START Study Group . HIV and STD risk behavior among 18- to 25-year-old men released from U.S. prisons: provider perspectives. AIDS Behav. 2003;7(2):131–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.MacGowan RJ, Margolis A, Gaiter J, et al. ; Project START Study Group . Predictors of risky sex of young men after release from prison. Int J STD AIDS. 2003;14(8):519–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ. Social context, sexual networks, and racial disparities in rates of sexually transmitted infections. J Infect Dis. 2005;191(suppl 1):S115–S122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Knittel AK, Snow RC, Griffith DM, Morenoff J. Incarceration and sexual risk: examining the relationship between men’s involvement in the criminal justice system and risky sexual behavior. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(8):2703–2714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Seal DW, Eldrige GD, Kacanek D, Binson D, MacGowan RJ. A longitudinal, qualitative analysis of the context of substance use and sexual behavior among 18- to 29-year-old men after their release from prison. Soc Sci Med. 2007;65(11):2394–2406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.International Center for Prison Studies World prison brief. Available at: www.prisonstudies.org/world-prison-brief. Accessed December 24, 2015