Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

To describe the strategies families report using to address the needs and concerns of siblings of children, adolescents, and young adults undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT).

METHODS:

A secondary semantic analysis was conducted of 86 qualitative interviews with family members of children, adolescents, and young adults undergoing HSCT at 4 HSCT centers and supplemented with a primary analysis of 38 additional targeted qualitative interviews (23 family members, 15 health care professionals) conducted at the primary center. Analyses focused on sibling issues and the strategies families use to address these issues.

RESULTS:

The sibling issues identified included: (1) feeling negative effects of separation from the patient and caregiver(s); (2) experiencing difficult emotions; (3) being faced with additional responsibilities or burdens; (4) lacking information; and (5) feeling excluded. Families and health care providers reported the following strategies to support siblings: (1) sharing information; (2) using social support and help offered by family or friends; (3) taking siblings to the hospital; (4) communicating virtually; (5) providing special events or gifts or quality time for siblings; (6) offering siblings a defined role to help the family during the transplant process; (7) switching between parents at the hospital; (8) keeping the sibling’s life constant; and, (9) arranging sibling meetings with a certified child life specialist or school counselor.

CONCLUSIONS:

Understanding the above strategies and sharing them with other families in similar situations can begin to address sibling issues during HSCT and can improve hospital-based, family-centered care efforts.

What’s Known on This Subject:

Siblings of pediatric patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplant have unmet needs and concerns. Family-centered care with support for siblings is recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics and others.

What This Study Adds:

Although many organizations recommend and offer support for siblings, strategies actually used by families with a child undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplant have not been described. This study reports the strategies used by 32 families to assist siblings.

Siblings of children with chronic illness often experience psychosocial challenges that can negatively impact their development. Literature reviews indicate that, as a group, siblings of children with chronic illness experience an elevated risk for psychosocial distress, poorer psychological functioning, engagement in fewer peer activities, and lower cognitive development scores.1–3 Siblings of patients with cancer have been reported to face similar challenges4: experiencing family separation,5 lack of attention,6 lack of information,7–9 and more responsibilities,7,10 with resulting feelings of sadness, loneliness, rejection, anxiety, anger, jealousy, and guilt. A recent systematic analysis and policy statement concludes that siblings of children with cancer are at risk and should receive supportive services,11 as does the American Academy for Pediatrics’ recommendation for family-centered care.12 Identifying the strategies families use to address these challenges would be helpful.

Siblings of children undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT), many of whom are patients with cancer, are also at risk.7 When a child is faced with HSCT, the entire family is affected by the experience.7,13 HSCT is an invasive treatment requiring extensive time in the hospital for the patient and at least 1 caregiver. Although much of the research and commentary about siblings of children undergoing HSCT have been about sibling donors,14–28 some studies have found increased risks for other siblings. Nondonor siblings can experience interruption in family life and isolation,7 lack of information and attention,29 loneliness, anxiety, lower self-esteem, school problems, and moderate levels of posttraumatic stress symptoms.30–32 Interestingly, rates of moderate-to-severe posttraumatic stress symptoms were equal among donor and nondonor siblings in 1 study.31 In addition, siblings have indicated that their needs are not being met and have made suggestions about how the health care team could better support them.13

In an effort to further understand the needs of siblings and the strategies used by families to meet these needs during HSCT, we conducted a secondary analysis of family interviews collected prospectively during the transplant process.33 We supplemented the secondary analysis with prospective interviews with family members of children, adolescents, and young adults (“children” henceforth is understood to include adolescents and young adults) undergoing HSCT and pediatric transplant health care providers. This study aims to provide an account of sibling issues during HSCT and the strategies families used to help them.

Methods

All phases of the study were approved by the institutional review boards of participating institutions and consent/assent was obtained from all participants.

Study Design

Phase I

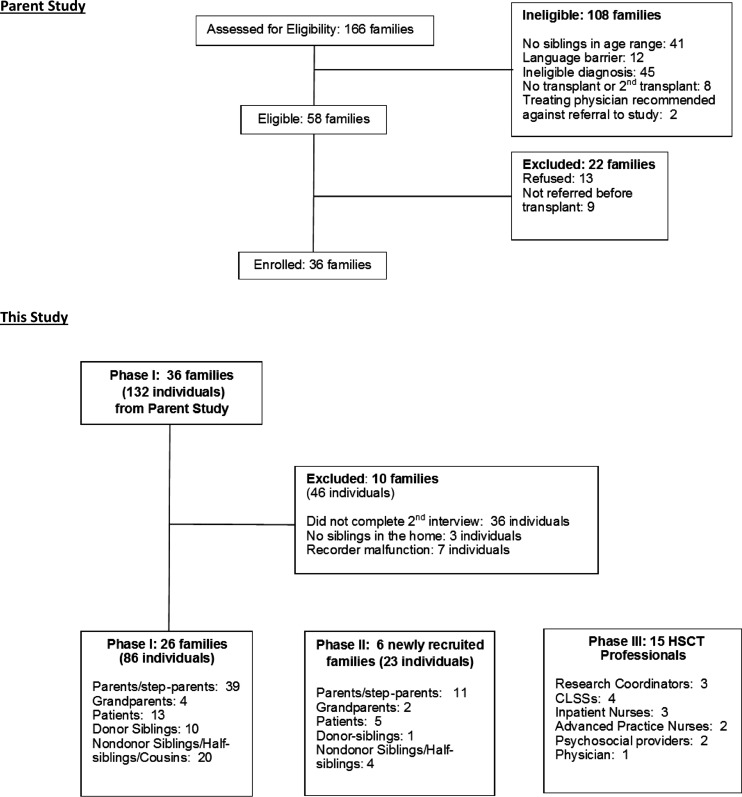

A secondary semantic analysis was conducted on qualitative interviews collected from 26 families at 4 sites (Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta [CHOA], The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Alberta Children’s Hospital, and Children’s Mercy Kansas City) (see Fig 1 for a description of family members and health care professionals interviewed in each phase). The parent study focused on family decision-making in pediatric HSCT and included interviewing children undergoing HSCT and their family members (ie, parents, grandparents, siblings, half siblings, and cousins) at 4 time points over the course of a year.33 Eligible families had a child undergoing HSCT with at least 1 sibling between the ages 9 and 22 years in the home. This report analyzed the second interview, which was conducted 5 to 9 months posttransplant, giving the families time to develop their own strategies.

FIGURE 1.

Explanation of sample for analysis.

Phase II

To supplement the secondary analysis, we interviewed 6 additional families at CHOA who met the Phase I eligibility criteria, asking each family member (ie, parents, grandparents, patients, siblings) to identify sibling issues during HSCT and strategies used to assist them. We attempted contact with 11 families; 2 (18%) refused and 3 (27%) could not be contacted.

Phase III

Twenty-seven health care professionals of the CHOA HSCT team were contacted and 15 (56%) agreed to be interviewed regarding recommended strategies to assist siblings.

Instrumentation

Phase I

A semistructured interview guide was created for the parent study. That study, however, was based on grounded theory, so as new issues arose in the analysis of interviews, questions were added to additionally probe these issues. The second interview, which provides data for the current analyses, asked if there was information the family members lacked, how each family member managed, and what the hardest part of HSCT was for each family member. About one-third of the way through the accrual, the following question was added to identify strategies used: “Everybody in the family helped your family through this really tough time. What did you do to get the family through?” Analysis for this report focused on strategies used to help siblings.

Phase II

A semistructured interview guide was developed to specifically collect data on sibling issues during HSCT and the strategies family used to meet their needs. Parents were asked: (1) “What did you do to include the siblings in fighting this cancer?” and (2) “Is there anything that you did to prepare the siblings for this process?” The siblings were asked to list all the things that they felt helped them during the transplant. Patients were asked what things the family did to help the siblings.

Phase III

Health care providers were asked to describe the strategies they recommend families use to reduce distress in siblings.

Analyses

All interviews were qualitatively coded using multilevel semantic analysis.34 T.W. developed the initial code dictionary, which was reviewed and edited by M.D.D. and finalized by R.D.P. T.W. then coded all transcripts from all 3 phases. L.C. coded a random 10% of the transcripts to assess interrater reliability. The 2 raters agreed on 95% (77/81) of the total codes and R.D.P. resolved the 4 disputed codes. The codes were combined into themes, which were agreed on by all authors, and simple frequencies of themes were calculated by the participant’s role in the family (ie, parent, grandparent, patient, donor sibling, nondonor sibling; nondonor siblings included half-siblings and cousins who lived in the home).

Two post hoc analyses were done. We compared adult (parents and grandparents) and child (patients and nondonor and donor siblings) reports of siblings’ concerns and strategies used to assist siblings. Second, we compared the frequencies of the health care providers’ and family members’/families’ strategies. All P values comparing the concern and strategy rates were determined using either χ2 tests or Fisher’s exact tests as appropriate. Statistical analyses were performed in SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC), and statistical significance was assessed at the .05 level. Because these analyses were exploratory, no adjustments for multiple hypothesis tests were made.

Results

In total, 109 family members and 15 health care providers were interviewed. Demographic characteristics of the family members are cataloged in Table 1. Table 2 describes family characteristics that might impact sibling issues, such as distance of the family home from the health care facility.

TABLE 1.

Demographics

| Characteristic | Parents/ Surrogates, 56 | Patients, 18 | At Home Siblings, 35 | Total, 109 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 25 (45) | 10 (56) | 20 (57) | 55 (50) |

| Female | 31 (55) | 8 (44) | 15 (43) | 54 (50) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | 38 (68) | 12 (67) | 19 (54) | 69 (63) |

| African-American | 16(29) | 5 (28) | 12(34) | 33(30) |

| Hispanic | 2(3) | 0 | 0 | 2(2) |

| White/Hispanic mix | 0 | 1(5) | 4(11) | 5(5) |

| Age | ||||

| Median age (y) | 42 | 16 | 16 | — |

| Age range (y) | 29–64 | 11–18 | 9–22 | — |

| Education | ||||

| Level | 56 (%) | — | — | — |

| ≥ College degree | 19 (34) | — | — | — |

| < College degree | 27(48) | — | — | — |

| Missing | 10 (18) | — | — | — |

—, no data.

TABLE 2.

Family Characteristics

| Family Income | n (%) | Federal Poverty Guidelines | Distance From Center >100 Miles, n (%) | Patient at a Hospital That Excludes <12-y-old Visitors, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| $5000–$19 999 | 2 (6) | 2 <100% | >100 | 11 (34) | Yes | 95 (87) |

| $5000–$19 999 | 4 (13) | 3 <150% | ≤100 | 14 (44) | No | 14 (13) |

| $40 000–$59 999 | 6 (19) | 1 <150% | Not known | 7 (22) | — | — |

| $60 000–$79 999 | 6 (19) | — | — | — | — | — |

| >$80 000 | 11 (34) | — | — | — | — | — |

| Missing | 3 (9) | — | — | — | — | — |

—, no data.

Sibling Issues and Concerns

Concerns mentioned about and by siblings included: (1) experiencing difficult emotions; (2) feeling negative effects of separation from the patient and caregiver(s); (3) being faced with additional responsibilities or burdens; (4) lacking information about the patient's medical situation; and (5) feeling excluded from the family battle against cancer (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Sibling Concerns Reported by Family Members

| Concern | Family Members, n = 109 | Parents, n = 50 | Grand-parents, n = 6 | Patients, n = 18 | Nondonor Siblings, n = 24 | Donor Siblings, n = 11 | P, Children Versus Adultsa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Emotional difficulty | 46 (42) | 18 (36) | 4 (67) | 6 (33) | 15 (63) | 3 (27) | .53 |

| Separation | 43 (39) | 18 (36) | 4 (67) | 7 (39) | 10 (42) | 4 (36) | .97 |

| Added responsibilities or burdens | 29 (27) | 11 (22) | 3 (50) | 3 (17) | 10 (42) | 2 (18) | .70 |

| Lack of information | 14 (13) | 2 (4) | 0 | 1 (6) | 8 (33) | 3 (27) | .006 |

| Feeling excluded | 14 (13) | 6 (12) | 0 | 1 (6) | 6 (25) | 1 (9) | .65 |

P values are derived from the comparison of adult and children concern rates. To obtain the frequencies and percentages for adults, we sum the parents and grandparents. To obtain the frequencies and percentages for children, we sum the patients, nondonor siblings, and donor siblings.

Strategies for Meeting Siblings’ Needs

Sharing Information

The most frequently used strategy (Table 4) was sharing information with siblings about the patient’s medical situation and the transplant process. This strategy included sharing age-appropriate or all information and reportedly resulted in siblings feeling both informed and included. Thirty-four (31%) family members used virtual communications, such as texting/calling/video chatting, as methods of sharing information. One mother commented on the importance of good communication:

TABLE 4.

Strategies Used to Assist Siblings

| Strategies | Families,a n = 32 | Family Members, n = 109 | Parents, n = 50 | Grandparents, n = 6 | Patients, n = 18 | Nondonor Siblings, n = 24 | Donor Siblings, n = 11 | Health Care Providers,n = 15 | P, Adults Versus Childrenb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Share information | 23 (72) | 62 (57) | 31 (62) | 3 (50) | 9 (50) | 15 (63) | 4 (36) | 6 (40) | .41 |

| Use social support | 23 (72) | 50 (46) | 26 (52) | 4 (67) | 5 (28) | 11 (46) | 4 (36) | 8 (53) | .10 |

| Take the siblings to the hospital | 19 (59) | 42 (39) | 21 (42) | 2 (33) | 7 (39) | 9 (38) | 3 (27) | 7 (47) | .58 |

| Virtual communications | 15 (47) | 34 (31) | 14 (28) | 3 (50) | 8 (44) | 8 (33) | 1 (9) | 13 (87) | .85 |

| Provide siblings with a special event or quality time | 12 (38) | 24 (22) | 12 (24) | 2 (33) | 2 (11) | 7 (29) | 1 (9) | 6 (40) | .44 |

| Assign the sibling a role or responsibility | 12 (38) | 23 (21) | 10 (20) | 1 (17) | 2 (11) | 7 (29) | 3 (27) | 6(40) | .70 |

| Switch off parents at hospital | 9 (28) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 12 (80) | N/A |

| Keep the sibling’s life as constant as possible | 8 (25) | 13 (12) | 8 (16) | 1 (17) | 2 (11) | 2 (8) | 0 | 5 (33) | .17 |

| Meet individually with a CCLS at the hospital | 7 (22) | 12 (11) | 7 (14) | 1 (17) | 2 (11) | 2 (8) | 0 | 15 (100) | .27 |

| Obtain counseling | 4 (13) | 6 (6) | 2(4) | 0 | 0 | 3 (13) | 1 (9) | 4 (27) | .42 |

N/A, not applicable.

Mentioned by at least 1 member of the family.

P values are derived from the comparison of adult and children strategy rates. To obtain the frequencies and percentages for adults, we sum the parents and grandparents. To obtain the frequencies and percentages for children, we sum the patients, nondonor siblings, and donor siblings.

“There’s no reason to avoid it. You have to talk about it. You have to keep each other informed to what you’re going through. If you’re scared, it’s okay, it’s a normal feeling. It’s not just like she’s going to have a shot; it’s a major surgery. Everyone needs to be informed about what’s going on and what to expect … because you’re all in one game together.”

Social Support and Taking the Siblings to the Hospital

The next 2 most frequently mentioned strategies were using social support, such as accepting help for the siblings (eg, transportation, meals, babysitting) from friends and family members and taking the siblings to the hospital. One sibling, who appreciated the help from relatives because their visits made it possible for both his mom and dad to be home, commented: “Yeah, it was pretty nice. I mean, we had other relatives come down here like my grandmamma, my aunt, and my grandpa. My uncle would come down and stay a week and a half with [patient], all night and all day. That way, my dad and my mom got to be here at the same time.” Another appreciated relatives, “as long as they know how to cook.” One mother used family members for transportation for the siblings: “We had a network of friends and family that just said, ‘Whatever you need, we’re here: if the boys need rides, if they need to be picked up.’”

Some families brought the siblings to the hospital. A father of such a family explained, “Everybody is there and goes through it and it just makes you stronger as a whole…. [Then the siblings can say] ‘I’ve been there with my brother the whole way through.’”

Providing Special Events and Offering or Assigning a Role

One-third of the families provided siblings with a special event just for the sibling or assigned the sibling a role or responsibility related to the HSCT experience. These special events included parties, vacations, special gifts, and privileges, like television and ice cream. Examples of roles included assisting with household responsibilities, caring for younger siblings, caring for the family pet, acting as a companion for the patient, writing cards to the patient, and organizing a fundraiser at school to help defray the family’s medical expenses. These roles were designed to increase the siblings’ feelings of importance and contribution to the family. For example, 1 father described assigning a role to the 11-year-old brother of a younger donor:

“I said, ‘Your bigger role is you are big brother. Little brother looks up to big brother …You are the example for him. I need for you to help me keep him happy. Keep him calm. When he wants to play, play with him. When he wants to be on the computer, you help him out. Do whatever you have to to be his big brother. Be there for him.’”

This father perceived that the strategy was successful in addressing early acting out behavior of the older sibling: “I think the biggest part was getting him involved and making him feel like he was an important member of the family. I think that’s what changed things around.”

Switching Caregivers Between Home and Hospital

Eighteen families (56%) had 1 parent as the primary caregiver at the hospital and 5 families (16%) elected to have both parents at the hospital full-time, using social support to help care for the siblings at home. Nine (28%) families used the strategy of switching caregivers between the patient at the hospital and the siblings at home, to allow parents to have time with the siblings. One sibling reported that he liked the switching off because he did not like just talking to his mom by phone. He explained, “I did not feel good about talking twice a day because I wanted to see my mom. But on the weekends my dad and my mom would switch out and I would be able to spend some time with my mom.”

Keeping Siblings’ Lives Constant, Meeting With a Certified Child Life Specialist or a Counselor

Other strategies mentioned by family members included keeping the sibling’s life as constant as possible (13 [12%] family members) and having siblings meet individually with a certified child life specialist (CCLS) at the hospital who was familiar with the patient’s care (12 [11%] family members). The siblings who met with a CCLS thought it was helpful, fun, and an effective method for talking about their feelings. One father thought talking to the CCLS would have helped the nondonor siblings: “She answered all of [donor sibling’s] questions and she was great for [donor], but someone needed to be there for [nondonor sibling] that was not mom and dad. We told him everything that was going on, but sometimes they don’t want to talk to parents. They want to talk to someone else.” Four (11%) siblings in 4 (13%) families received counseling at school.

Comparison of Adult and Child Reports

One issue, lack of information about the patient’s medical condition, was mentioned more frequently by children than adults (23% vs 4%; P = .006) (Table 3). There were no significant differences in the frequency with which adults and children reported strategies used to assist siblings (Table 4).

Comparison of Health Care Providers’ and Families’ Mentions of Strategies

Five strategies were recommended more frequently by health care providers than used by family members or by family units (as reported by at least 1 family member): switching off parents at the hospital, communicating virtually, keeping siblings lives constant, meeting with a CCLS, and obtaining counseling (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Health Care Providers’ Versus Family Members’ Strategies

| Strategies | Families,a n = 32 | Family Members, n = 109 | Provider, n = 15 | P, Providers Versus Families | P, Providers Versus Family Members |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |||

| Share information | 23 (72) | 62 (57) | 6 (40) | .04 | .22 |

| Use social support | 23 (72) | 50 (46) | 8 (53) | .21 | .59 |

| Take siblings to the hospital | 19 (59) | 42 (39) | 7 (47) | .41 | .55 |

| Virtual communication | 15 (47) | 34 (31) | 13 (87) | .01 | <.001 |

| Special event for sibling | 12 (38) | 24 (22) | 6 (40) | .87 | .19 |

| Role or responsibility for sibling | 12 (38) | 23 (21) | 6 (40) | .87 | .11 |

| Switch off parents at hospital | 9 (28) | N/A | 12 (80) | .001 | N/A |

| Keep sibling’s life constant | 8 (25) | 13 (12) | 5 (33) | .55 | .04 |

| Meet with CCLS | 7 (22) | 12 (11) | 15 (100) | <.001 | <.001 |

| Obtain counseling | 4 (13) | 6 (6) | 4 (27) | .25 | .02 |

N/A, not applicable.

Mentioned by at least 1 member of the family.

Discussion

The multiple concerns that were reported by and about siblings of children undergoing HSCT included emotional difficulties, separation from and disruption of the family, additional burdens, lack of information, and exclusion. These concerns are similar to those uncovered in past research7,29,31,32,35–38 and validate those findings in a larger sample that includes input from all family members, enriching the literature. The 10 strategies to address the needs of siblings during HSCT have also been recommended previously.7,8,13,38–40 This report therefore supplements previous recommendations with family members’ own descriptions of the strategies that were actually used and their frequency. These data can provide health care providers with a list of strategies to present to families facing HSCT and can assist health care providers in meeting the recent recommendations to support siblings as standard of care.11,12

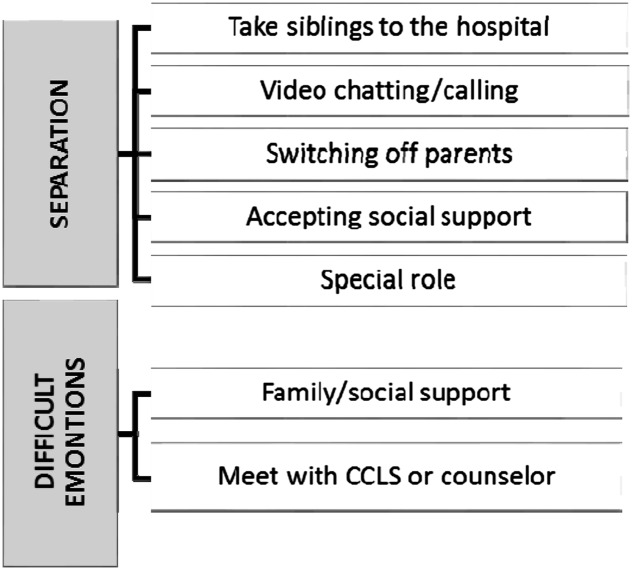

Several of the strategies used by families address >1 of their concerns (see Fig 2 for 2 examples). Interestingly, 5 of the most frequently used strategies could be aimed at decreasing the ill-effects of separation, the second most frequently mentioned concern. However, a strategy may also contribute to a concern. Assigning a special role to the sibling, rather than leading to inclusion, as is generally the intention, may result in 1 of the concerns frequently mentioned: extra responsibilities at home.7 Interestingly, the adults and children did not differ in their reports of the strategies used.

FIGURE 2.

Strategies addressing sibling concerns.

The inclusion of both families and health care providers allowed for the post hoc analysis of their perspectives and interesting differences emerged. The largest differences found were virtual communication, meeting with a CCLS, or switching caregivers at the hospital, with health care providers recommending these more frequently than families reported using them. These differences illustrate the potential disconnect between what health care professionals recommend and what occurs in practice.

The barriers families experience and differences in available resources may in part explain why families do not use the breadth of strategies recommended by health care professionals. For example, some parents may have chosen a particular pattern of staying at the hospital, both caregivers at the hospital versus switching off, because of extenuating circumstances, such as occupation flexibility, distance between home and hospital (40% of families lived >100 miles from the transplant center), and the availability of social support. The financial resources available to the family could also dictate how often strategies, such as providing the sibling with a special event, are used. Two of our families were below the federal poverty line and an additional 4 were below 150% of that guideline. Future research is needed to better understand such barriers and the additional support that may be required from the treating health care team to circumvent them. Nurses, social workers, and CCLSs can then aid each family in developing a plan, using the strategies mentioned in this article, that is tailored to the family’s situation.

The 1 concern that adults and children differed on was whether the siblings received adequate information about the patient’s medical condition, with few adults mentioning this concern whereas one-fourth of children reported it. Yet 62% of parents reported that sharing information was a strategy used. This result suggests that parental sharing of information may need to be supplemented. The 1 unanimously health care provider–recommended strategy, providing a CCLS contact for siblings, could be used to alleviate this disconnect. Designing a means of sharing information with the siblings may be a key strategy for all families, with the other 9 strategies used as well, depending on the family situation.

One major limitation of the current study is that the primary aim of the parent study was to describe family decision-making regarding a pediatric HSCT, not to report siblings’ issues and strategies to overcome them. The parent study’s interviews were based on grounded theory, so each participant was not asked the same set of questions and all were not asked directly about the strategies used. Therefore, we supplemented the original data with an additional 23 family members and 15 health care provider interviews, which specifically asked about strategies. Notably, the additional targeted interviews contain approximately twice the average number of codes per interview than the original interviews as a result of the improved specificity of the interviews. Additionally, adult and children concern and strategy rates were compared while assuming the 2 groups were independent. Nested or paired models could be considered, although the assumption of independence is generally considered a more conservative approach.

Conclusions

This analysis corroborates earlier findings that siblings of patients with cancer have unique, unmet needs,7,29,31,32,35,36,41 and provides novel perspectives from family members about the strategies they employed in helping the siblings navigate the HSCT experience. We suggest that the strategy unanimously suggested by the health care providers and recommended in a recent guideline,17 providing a CCLS or other psychosocial services to the siblings, could be effective in alleviating several of the siblings’ concerns. However, because each family has a unique dynamic, being able to coach families about a variety of strategies is important. Health care professionals should be attuned to the unique nuances of each family’s situation and tailor their recommendations for helping siblings accordingly.

Acknowledgment

We thank Minisha Lohani for her careful review of the manuscript.

Glossary

- CCLS

certified child life specialist

- CHOA

Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta

- HSCT

hematopoietic stem cell transplant

Footnotes

Ms White participated in the conceptualization and design of the study, conducted prospective interviews, and drafted the initial manuscript; Mr Hendershot participated in the conceptualization and design of the study, conducted prospective interviews, and reviewed and edited each draft; Ms Dixon and Ms Cox conducted the qualitative analyses and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Ms Pelletier and Drs Alderfer and Stegenga participated in the design of the study and coordinated and supervised data collection at three of the original 4 sites and critically reviewed the manuscript; Dr Switchenko participated in the design of the study, designed and conducted the statistical analyses, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Drs Haight and Hinds participated in the conceptualization of the study and critically reviewed the manuscript; Dr Pentz participated in the conceptualization and design of the study, coordinated and supervised data collection at 1 of the original sites, conducted prospective interviews, and critically reviewed the manuscript; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: The research reported in this publication was supported in part by the Biostatistics and Bioinformatics Shared Resource of Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University and National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute award P30CA138292. The parent study was supported by National Cancer Institute grant 1R21CA131875-01A1. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Sharpe D, Rossiter L. Siblings of children with a chronic illness: a meta-analysis. J Pediatr Psychol. 2002;27(8):699–710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barlow JH, Ellard DR. The psychosocial well-being of children with chronic disease, their parents and siblings: an overview of the research evidence base. Child Care Health Dev. 2006;32(1):19–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams PD. Siblings and pediatric chronic illness: a review of the literature. Int J Nurs Stud. 1997;34(4):312–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alderfer MA, Long KA, Lown EA, et al. Psychosocial adjustment of siblings of children with cancer: a systematic review. Psychooncology. 2010;19(8):789–805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sargent JR, Sahler OJZ, Roghmann KJ, et al. Sibling adaptation to childhood cancer collaborative study: siblings’ perceptions of the cancer experience. J Pediatr Psychol. 1995;20(2):151–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sloper P. Experiences and support needs of siblings of children with cancer. Health Soc Care Community. 2000;8(5):298–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilkins KL, Woodgate RL. An interruption in family life: siblings’ lived experience as they transition through the pediatric bone marrow transplant trajectory. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2007;34(2):E28–E35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carr-Gregg M, White L. Siblings of paediatric cancer patients: a population at risk. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1987;15(2):62–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nolbris M, Hellstrom AL. Siblings’ needs and issues when a brother or sister dies of cancer. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2005;22(4):227–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sahler OJZ, Roghmann KJ, Carpenter PJ, et al. Sibling adaptation to childhood cancer collaborative study: prevalence of sibling distress and definition of adaptation levels. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1994;15(5):353–366 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gerhardt CA, Lehmann V, Long KA, Alderfer MA. Supporting siblings as a standard of care in pediatric oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62(suppl 5):S750–S804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Committee On Hospital Care and Institute For Patient- And Family-Centered Care . Patient- and family-centered care and the pediatrician’s role. Pediatrics. 2012;129(2):394–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilkins KL, Woodgate RL. Supporting siblings through the pediatric bone marrow transplant trajectory: perspectives of siblings of bone marrow transplant recipients. Cancer Nurs. 2007;30(5):E29–E34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chan KW, Gajewski JL, Supkis D Jr, Pentz R, Champlin R, Bleyer WA. Use of minors as bone marrow donors: current attitude and management. A survey of 56 pediatric transplantation centers. J Pediatr. 1996;128(5, pt 1):644–648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Curran WJ. Beyond the best interests of a child. Bone marrow transplantation among half-siblings. N Engl J Med. 1991;324(25):1818–1819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hardwig J. What about the family? Hastings Cent Report. 1990;20(2):5–10 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dwyer J, Vig E. Rethinking transplantation between siblings. Hastings Cent Rep. 1995;25(5):7–19 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jansen LA. Child organ donation, family autonomy, and intimate attachments. Camb Q Healthc Ethics. 2004;13(2):133–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jecker NS. The role of intimate others in medical decision making. Gerontologist. 1990;30(1):65–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joffe S, Kodish E. Protecting the rights and interests of pediatric stem cell donors. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;56(4):517–519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.MacLeod KD, Whitsett SF, Mash EJ, Pelletier W. Pediatric sibling donors of successful and unsuccessful hematopoietic stem cell transplants (HSCT): a qualitative study of their psychosocial experience. J Pediatr Psychol. 2003;28(4):223–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Opel DJ, Diekema DS. The case of A.R.: the ethics of sibling donor bone marrow transplantation revisited. J Clin Ethics. 2006;17(3):207–219 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pentz R. Duty and altruism: alternative analyses of the ethics of sibling bone marrow donation. J Clin Ethics. 2006;17(3):227–230 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pentz RD. Healthy sibling donation of G-CSF primed stem cells: a call for research. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2006;46(4):407–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pentz RD, Chan KW, Neumann JL, Champlin RE, Korbling M. Designing an ethical policy for bone marrow donation by minors and others lacking capacity. Camb Q Healthc Ethics. 2004;13(2):149–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shama WI. The experience and preparation of pediatric sibling bone marrow donors. Soc Work Health Care. 1998;27(1):89–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weisz V, Robbennolt JK. Risks and benefits of pediatric bone marrow donation: a critical need for research. Behav Sci Law. 1996;14(4):375–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wiener LS, Steffen-Smith E, Fry T, Wayne AS. Hematopoietic stem cell donation in children: a review of the sibling donor experience. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2007;25(1):45–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pentz RD, Alderfer MA, Pelletier W, et al. Unmet needs of siblings of pediatric stem cell transplant recipients. Pediatrics. 2014;133(5). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/133/5/e115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Packman WL, Crittenden MR, Schaeffer E, Bongar B, Fischer JB, Cowan MJ. Psychosocial consequences of bone marrow transplantation in donor and nondonor siblings. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1997;18(4):244–253 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Packman W, Gong K, VanZutphen K, Shaffer T, Crittenden M. Psychosocial adjustment of adolescent siblings of hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2004;21(4):233–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Packman W, Beck V, VanZutphen K, Long J, Spengler GAT. The human figure drawing with donor and nondonor siblings of pediatric bone marrow transplant patients. Art Ther. 2003;20(2):83–91 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pentz RD, Pelletier W, Alderfer MA, Stegenga K, Fairclough DL, Hinds PS. Shared decision-making in pediatric allogeneic blood and marrow transplantation: what if there is no decision to make? Oncologist. 2012;17(6):881–885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kripendorf K. Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Packman W, Crittenden M, Fischer JBR, Schaeffer E, Bongar B, Cowan MJ. Siblings’ perceptions of the bone marrow transplantation process. J Psychosoc Oncol. 1997;15(3-4):81–105 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Packman W, Weber S, Wallace J, Bugescu N. Psychological effects of hematopoietic SCT on pediatric patients, siblings and parents: a review. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2010;45(7):1134–1146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pot-Mees CC. The Psychological Effects of Bone Marrow Transplantation in Children. Delft, Netherlands: Eburon Delft; 1989 [Google Scholar]

- 38.American Cancer Society What helps kids with cancer and their brothers and sisters? Available at: www.cancer.org/treatment/childrenandcancer/whenyourchildhascancer/childrendiagnosedwithcancerdealingwithdiagnosis/children-diagnosed-with-cancer-dealing-with-diagnosis-what-helps-kids. Accessed December 1, 2014

- 39.American Society of Clinical Oncology Family, friends, and relationships. Available at: www.cancer.net/navigating-cancer-care/young-adults/family-friends-and-relationships/cancer-and-your-siblings. Accessed December 1, 2014

- 40.Wilkins KL, Woodgate RL. A review of qualitative research on the childhood cancer experience from the perspective of siblings: a need to give them a voice. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2005;22(6):305–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pot-Mees CC, Zeitlin H. Psychosocial consequences of bone marrow transplantation in children: A preliminary communication. J Psychosoc Oncol. 1987;5(2):73–81 [Google Scholar]