Abstract

Background: DNA methylation is influenced by diet and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), and methylation modulates gene expression.

Objective: We aimed to explore whether the gene-by-diet interactions on blood lipids act through DNA methylation.

Design: We selected 7 SNPs on the basis of predicted relations in fatty acids, methylation, and lipids. We conducted a meta-analysis and a methylation and mediation analysis with the use of data from the CHARGE (Cohorts for Heart and Aging Research in Genomic Epidemiology) consortium and the ENCODE (Encyclopedia of DNA Elements) consortium.

Results: On the basis of the meta-analysis of 7 cohorts in the CHARGE consortium, higher plasma HDL cholesterol was associated with fewer C alleles at ATP-binding cassette subfamily A member 1 (ABCA1) rs2246293 (β = −0.6 mg/dL, P = 0.015) and higher circulating eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) (β = 3.87 mg/dL, P = 5.62 × 1021). The difference in HDL cholesterol associated with higher circulating EPA was dependent on genotypes at rs2246293, and it was greater for each additional C allele (β = 1.69 mg/dL, P = 0.006). In the GOLDN (Genetics of Lipid Lowering Drugs and Diet Network) study, higher ABCA1 promoter cg14019050 methylation was associated with more C alleles at rs2246293 (β = 8.84%, P = 3.51 × 1018) and lower circulating EPA (β = −1.46%, P = 0.009), and the mean difference in methylation of cg14019050 that was associated with higher EPA was smaller with each additional C allele of rs2246293 (β = −2.83%, P = 0.007). Higher ABCA1 cg14019050 methylation was correlated with lower ABCA1 expression (r = −0.61, P = 0.009) in the ENCODE consortium and lower plasma HDL cholesterol in the GOLDN study (r = −0.12, P = 0.0002). An additional mediation analysis was meta-analyzed across the GOLDN study, Cardiovascular Health Study, and the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Compared with the model without the adjustment of cg14019050 methylation, the model with such adjustment provided smaller estimates of the mean plasma HDL cholesterol concentration in association with both the rs2246293 C allele and EPA and a smaller difference by rs2246293 genotypes in the EPA-associated HDL cholesterol. However, the differences between 2 nested models were NS (P > 0.05).

Conclusion: We obtained little evidence that the gene-by–fatty acid interactions on blood lipids act through DNA methylation.

Keywords: DNA methylation, epidemiology, fatty acids, genetic variants, plasma lipids

INTRODUCTION

DNA methylation, which is one type of epigenetic modification, has been reported to be associated with a wide array of clinical diseases including cancer (1), atherosclerosis (2), obesity (3), inflammation (4), Alzheimer disease (5), type 2 diabetes (6), and dyslipidemia (7). The molecular effects of DNA methylation depend on the location of methylated cytosine-phosphate-guanine (CpG) sites. Compared with CpG sites located within the gene body, methylation of promoter CpG islands is more likely to affect gene expression (8). DNA-methylation patterns can be affected by both environmental factors and genetic variants, thereby leading to their hypothetical mechanistic roles in gene-by-environment interactions.

Fatty acids have been shown to affect DNA methylation in in vitro and cell systems. Specifically, arachidonic acid (AA),39 DHA (9), palmitic acid (PA), oleic acid (OA) (10), and EPA (11) were shown to affect the methylation of fatty acids synthetase 2 in mice, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator-1 α (PPARGC1A), and the tumor suppressor CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein δ in humans, respectively. However, how fatty acids influence DNA methylation is not entirely clear. Gene silencing of the DNA methyltransferase isoform 3B in human muscle cells was shown to prevent palmitate-induced methylation of PPARGC1A (10), which suggested that the mechanism of the effect of fatty acids on DNA methylation may involve DNA methyltransferase.

In addition, accumulating evidence suggests a relation between DNA methylation and sequence variants. For instance, a genetic manipulation study showed that methylation patterns are determined by the local sequence (12). The genetic regulation of DNA methylation is widespread in humans (13–17). The existence of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within the expression quantitative trait loci and methylation quantitative trait loci (18) has suggested a potential link between SNPs and DNA methylation, but the underlying mechanism is unclear. On the basis of the correlation between DNA methylation and gene expression and evidence of the association of DNA methylation with both genetic variants and fatty acids, we hypothesized that DNA methylation may in part explain the observed gene–fatty acid interactions in circulating lipids (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1 .

Hypothesis of the study. SNP, single nucleotide polymorphisms.

To test our hypothesis, we selected 7 candidate SNPs on the basis of their relations to circulating fatty acids and plasma lipids and their potential to undergo DNA methylation. We conducted a meta-analysis across 7 cohorts in the CHARGE (Cohorts for Heart and Aging Research in Genomic Epidemiology) consortium, a methylation analysis in the GOLDN (Genetics of Lipid Lowering Drugs and Diet Network) study, and a gene-expression analysis with the use of data from the ENCODE (Encyclopedia of DNA Elements) consortium to analyze the associations on the outcome of plasma lipids and DNA methylation of the candidate gene, respectively. An additional replication of methylation analyses were performed in the CHS (Cardiovascular Health Study) and the MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis).

METHODS

Study populations

Meta-analysis of 7 cohorts in the CHARGE consortium

The study included the following 7 cohorts in the CHARGE consortium: the Three-City Study (19), the ARIC (Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities) study (20), the CHS (21), the GOLDN study (22), the Invecchiare in Chianti (InCHIANTI) (23), the MESA (24), and the Women’s Genome Health Study (25). Details of these 7 cohorts are described in Supplemental Methods. This study was approved by the institutional review board of each cohort, and informed consent was received from all participants or their representatives. To limit the variation of genetic structures in populations of different ethnicities, nonwhite participants were excluded from the study.

SNP selection and genotyping in each cohort

We developed 7 inclusion criteria and one exclusion criterion to select the most-relevant SNPs (Supplemental Methods). SNPs that meeting all inclusion criteria (criteria 1–7) were first added to the list, and those SNPs that meeting the exclusion criterion (criterion 8) were excluded from the list. Criterion 1 required the SNPs to be located within the genes related to the phenotype of interest (plasma lipids), which was ascertained by querying the gene name in the PubMed-Gene database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/). Criterion 2 required the SNPs to be related to the exposure of interest (fatty acids) if the SNPs were located within the genes, which contain the response element for fatty acids, the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors response element, or that the expressions of the genes have been reported to be affected by fatty acids. (26). Criterion 3 was limited to the SNPs with a minor allele frequency >1%. SNPs were predicted to be related to DNA methylation if they met one of the following criteria for DNA methylation: being located close to CpG island (criterion 4), being located within a promoter region defined as within a 3-kb distance from the transcription start site provided by the RefSeq Gene database (file “refGene.txt.gz” on http://hgdownload.soe.ucsc.edu/goldenPath/hg19/database/) downloaded from the University of California, Santa Cruz genome browser (2 February 2012) (criterion 5), being located within regions reported to have a tissue differential DNA methylation status (27) (criterion 6), or being located within regions reported to have tissue differential chromatin status (28) (criterion 7). Eight candidate SNPs were selected from the list of 323 SNPs located within 40 genes, which have been reported to be associated with plasma lipids in genome-wide association studies (29–36). The exclusion criterion (criterion 8) excluded SNPs in high-linkage disequilibrium (R2 > 0.8). As a result, 7 SNPs were included in the analysis, namely apolipoprotein E (APOE) rs405509, >ATP-binding cassette subfamily A member 1 (ABCA1) rs2246293, 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase rs3761740, apolipoprotein A5 rs662799, proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin-type 9 rs2479409, hepatocyte nuclear factor-1 homeobox A rs1169288, and hepatocyte nuclear factor-1 homeobox A rs1169287. Details of genotyping methods in each cohort are described in Supplemental Table 1.

Biochemical and circulating fatty acid measurements in each cohort

Plasma triglycerides and HDL cholesterol were measured with the use of enzymatic assays described in Supplemental Methods. We focused on 7 circulating fatty acids including PA, OA, linoleic acid, AA, α-linolenic acid (ALA), EPA, and DHA. Circulating fatty acids were measured in total plasma (Three-City Study and InCHIANTI), plasma phospholipids (ARIC study, CHS, and MESA), or erythrocytes (GOLDN study and Women’s Genome Health Study) as described in Supplemental Methods. Fatty acids were expressed as the percentage of total fatty acids. Information for the covariates in this study was collected through standard questionnaires or measurements as described in Supplemental Methods.

DNA methylation in the GOLDN study, CHS, and MESA

Caucasian subjects with both methylation and fatty acid data available were included in the analysis, and the total numbers if subjects in the GOLDN study, CHS, and MESA were 991, 175, and 582, respectively. DNA methylation was measured with the use of the Infinium Human Methylation 450K BeadChip (Illumina) in CD4+ T cells (37), whole blood, and monocytes for the GOLDN study, CHS, and MESA, respectively. The measurement of methylation was expressed as the proportion of total signal from the methylation-specific probe or color channel. Details are described in Supplemental Methods. A surrogate variable analysis was performed to identify batch effects in the CHS (38). No surrogate variables were shown to be associated (P < 0.01) with the outcome in European-ancestry participants. The probes included in the current analysis passed the methylation quality control in each cohort (39, 40).

DNA methylation and gene expression in the ENCODE consortium

With the use of databases of the ENCODE consortium, methylation and gene-expression data across all 17 cell lines with relevant information were downloaded (20 June 2014) from the University of California, Santa Cruz genome browser HAIB Methyl450 track (version hg19) and Duke Affymetrix Array track (version hg19), respectively. The methylation of each CpG site was represented by a score that was 1000 times the proportion of the intensity value from the methylated bead type from the sum of the intensity values from both methylated and unmethylated bead types plus 100. The range of the methylation score was from 0 to 1000. A gene expression value was represented by a score that was defined as 100 times the signal value linearly scaled for that particular cell type and ranging from 0 to 1000.

Statistical analysis

Association analyses on plasma lipids as outcomes with the use of meta-analysis in the CHARGE consortium

Gene–fatty acid interactions and their associations on plasma lipids were tested with the use of a meta-analysis approach within 7 participating cohorts. For outcomes of both triglycerides and HDL cholesterol, 3 separate linear regression analyses were conducted by each cohort to generate regression coefficients (β) and robust SEs of 1) the mean effects of the genotypes of the 7 SNPs, 2) the mean effects of circulating fatty acids (PA, OA, LA, AA, ALA, EPA, and DHA), and 3) the interaction effects of SNPs and circulating fatty acids in models that included terms for both main effects and an interaction term. A meta-analysis was performed on the basis of the regression coefficients and robust SEs provided by each cohort with the use of an inverse variance–weighted, fixed-effects approach. Two independent analysts performed the meta-analysis with R “rmeta” package (version 2.16, Thomas Lumley, 2012) and METAL software (version March 2011, Abecasis Lab, School of Public Health, University of Michigan, MI) (41). Bonferroni correction for multiple testing was based on 49 tests of interactions (7 SNPs × 7 fatty acids), and the corrected threshold of significance was 0.001 (α = 0.05 ÷ 49).

All analyses were adjusted for age (continuous), sex (binary), study center (as applicable), and population structure or pedigree (as applicable) in model 1. To account for potential confounding by other environmental factors, model 2 included additional adjustments for BMI (in kg/m2; continuous), smoking status (categorical: never compared with past compared with current smokers), physical activity (continuous on the basis of the study-specific metric), alcohol intake (categorical: current compared with former or never), current estrogen therapy (categorical: yes or no), current use of a lipid-lowering medication (categorical: yes or no), education level (categorical: a cohort-specific metric), total energy intake (, kcal/d; continuous), dietary total fat intake (percentage of total energy intake/d; continuous), glycemic load (if applicable; g/d; quintiles of continuous), dietary total folate intake (if applicable; μg/d; continuous), and dietary vitamin B-12 intake (if applicable; μg/d; continuous). A log transformation was performed for triglycerides to reduce the effects of a few influential observations as a result of the skewed distribution of tryglycerides.

Association analyses on methylation as outcome in the GOLDN study

With the use of DNA-methylation data from the GOLDN study population, we conducted linear regressions to estimate the mean effects of genotypes on the DNA methylation of each CpG site located within the same genetic region, the mean effects of fatty acids on DNA methylation, and interactions between genotypes and fatty acids on the DNA methylation. The methylation analyses were adjusted for age (y; continuous), sex (binary), study center (categorical), pedigree, and principal components for cellular purity and population structure.

Correlation analyses with data in the GOLDN study and ENCODE consortium

We used the Pearson correlation to examine the correlations between DNA methylation and plasma lipids in the GOLDN study. With the use of data from the ENCODE consortium, we obtained Pearson correlation coefficients between methylation and gene expression.

Mediation analyses in the GOLDN study, CHS, and MESA

To explore whether methylation mediated associations and interactions with plasma lipids, we assessed the effect of including DNA methylation as a covariate in the models relating the genotype, fatty acids, and their interaction terms to plasma lipid outcomes. Bootstrap analyses (42) were conducted to test the significance of differences in gene–fatty acid associations after including DNA methylation as a covariate. Analyses were adjusted for age (y; continuous), sex (binary), study center (categorical), pedigree, population structure, and white cell proportion (if applicable). A meta-analysis was performed on the basis of the regression coefficients and robust SEs provided by each cohort with the use of an inverse variance–weighted, fixed-effects approach through METAL software (41) and R software by 2 independent analysts. The programs SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc.) and STATA 12.1 (StataCorp LP) were used to conduct the analysis.

RESULTS

Population characteristics

Population characteristics, plasma lipids, and circulating fatty acids are shown for each cohort in Table 1. In total, there were 10,472 subjects involved in the current study across the 7 cohorts. Mean concentrations of plasma lipids were generally similar across the 7 cohorts. Likewise, fatty acids percentages were generally similar in cohorts that measured fatty acids in the same compartment.

TABLE 1.

Population characteristics, blood lipids, and circulating fatty acids in each cohort1

| Circulating fatty acids, total fatty acids, % |

|||||||||||||

| n | Age, y | Women, % | HDL, mg/dL | Triglycerides, mg/dL | Compartment | PA | OA | LA | AA | ALA | EPA | DHA | |

| 3C (19) | 1240 | 74 ± 52 | 60 | 60.8 ± 15.4 | 113.2 ± 56.8 | Plasma | 28.3 ± 5.8 | 20.4 ± 3.9 | 24.7 ± 5.5 | 6.7 ± 1.9 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.6 | 2.4 ± 0.8 |

| InCHIANTI (23) | 1002 | 68 ± 15 | 55 | 56.3 ± 15.0 | 123.4 ± 65.6 | Plasma | 22.5 ± 2.4 | 25.8 ± 3.7 | 24.9 ± 3.9 | 8.0 ± 1.9 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 2.3 ± 0.8 |

| ARIC study (20) | 3385 | 54 ± 6 | 53 | 52.0 ± 16.9 | 137.4 ± 92.3 | Plasma phospholipids | 25.4 ± 1.7 | 8.6 ± 1.1 | 22.0 ± 2.7 | 11.5 ± 2.0 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.3 | 2.8 ± 0.9 |

| CHS (21) | 2399 | 72 ± 5 | 62 | 53.8 ± 14.3 | 146.2 ± 84.7 | Plasma phospholipids | 25.5 ± 1.6 | 7.6 ± 1.1 | 20.0 ± 2.5 | 10.9 ± 1.9 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.4 | 3.0 ± 1.0 |

| MESA (24) | 674 | 62 ± 10 | 53 | 52.7 ± 16.1 | 131.4 ± 79.0 | Plasma phospholipids | 25.8 ± 1.9 | 8.3 ± 1.2 | 20.9 ± 3.0 | 12.1 ± 2.2 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.7 | 3.7 ± 1.4 |

| GOLDN study (22) | 1120 | 48 ± 16 | 52 | 47.1 ± 13.1 | 138.8 ± 115.8 | Erythrocytes | 22.8 ± 1.2 | 16.1 ± 1.1 | 12.9 ± 1.4 | 13.6 ± 1.2 | 0.1 ± 0.04 | 0.5 ± 0.3 | 3.0 ± 0.9 |

| WGHS (25) | 652 | 54 ± 7 | 100 | 54.2 ± 14.7 | 142.3 ± 88.5 | Erythrocytes | 23.4 ± 2.3 | 15.0 ± 1.5 | 12.3 ± 1.4 | 12.7 ± 2.3 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 3.3 ± 1.0 |

AA, arachidonic acid; ALA, α-linolenic acid; ARIC, Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities; CHS, Cardiovascular Health Study; GOLDN, Genetics of Lipid Lowering Drugs and Diet Network; InCHIANTI, Invecchiare in Chianti; LA, linoleic acid. MESA, Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis; OA, oleic acid; PA, palmitic acid; WGHS, Women's Genome Health Study; 3C, Three-City Study.

Mean ± SD (all such values).

Association analyses on plasma lipids as outcomes with the use of meta-analysis in the CHARGE consortium

At the corrected threshold of significance (P < 0.001), we did not observe significant interactions between 7 SNPs and 7 circulating fatty acids on plasma HDL cholesterol and triglycerides (Supplemental Tables 2 and 3). However, in nominal interactions (P < 0.05), we showed 2 loci that approached significance for both their mean effects and interaction analyses with circulating fatty acids, specifically ABCA1 rs2246293 and APOE rs405509.

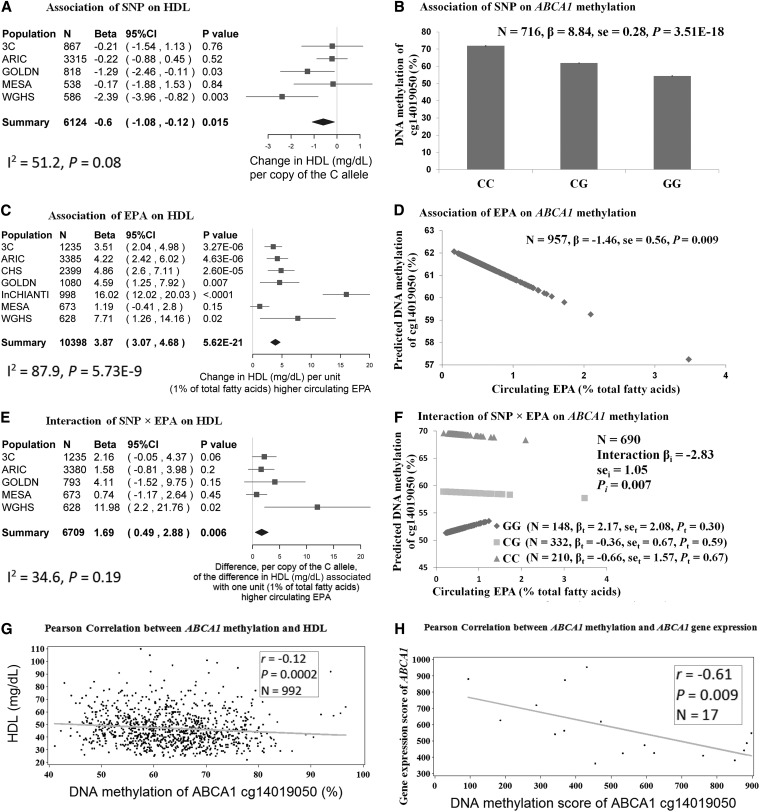

At ABCA1, we showed that the C allele of rs2246293 was nominally associated with a lower mean HDL cholesterol (β = −0.6 mg/dL per C allele, P = 0.015 in model 2) (Figure 2A). A higher mean EPA (percentage of total circulating fatty acids) was associated with greater plasma HDL cholesterol (β = 3.87 mg/dL per 1% higher EPA, P = 5.62 × 1021 in model 1) (Figure 2C). In addition, the mean difference in HDL cholesterol associated with a 1% higher circulating EPA was dependent on the genotype at rs2246293 (P = 0.006); we estimated this difference was 1.69 mg/dL higher for each additional C allele (Figure 2E). In other words, the association of EPA with HDL cholesterol was stronger in carriers of the C allele.

FIGURE 2 .

Relations in plasma HDL cholesterol, EPA, and SNP, DNA methylation, and gene expression at the ABCA1 locus. Mean effects of ABCA1 rs2246293 on the outcome of HDL cholesterol (model 2) and methylation of ABCA1 cg14019050 are presented in a forest plot with a meta-analysis in the CHARGE consortium (A) and bar charts by genotype in the GOLDN study (B), respectively. Mean effects of circulating EPA on the outcome of HDL cholesterol (model 1) and methylation of ABCA1 cg14019050 are presented in a forest plot with a meta-analysis in the CHARGE consortium (C) and bar charts by genotype in the GOLDN study (D), respectively. Interactions of rs2246293 × EPA on the outcome of HDL cholesterol (model 1) and methylation of ABCA1 cg14019050 are presented in a forest plot with a meta-analysis in the CHARGE consortium (E) and plot with genotype-dependent regression lines in the GOLDN study (F), respectively. In forest plots, the estimated β and its 95% CI, which illustrated the changes in plasma HDL cholesterol per copy of the rs2246293 C allele in panel A, the changes in plasma HDL cholesterol per unit (percentage of total fatty acid) of higher circulating EPA in panel C, and association with each 1% higher percentage of circulating EPA with HDL cholesterol per copy of the rs2246293 C allele in panel E, respectively, are represented by the filled square and horizontal line for each population or the filled diamond for the summary. In panel F, βi, sei, and Pi represent the regression coefficient, SE, and corresponding significance for the interaction term, respectively, which were interpreted as the association of each 1% higher percentage of circulating EPA with methylation of cg14019050 per copy of the rs2246293 C allele, whereas βt, set, and Pt represent the regression coefficient, SE, and significance for a trend, respectively, which were interpreted as the association of circulating EPA with cg14019050 methylation according to 3 genotype groups of rs2246293 (GG, CG, and CC). Pearson correlations of cg14019050 methylation with HDL cholesterol in the GOLDN study (G) and with the gene expression of ABCA1 in the ENCODE consortium (H), respectively, are shown, in which each black dot represents one observation, each gray line represents the regression line, and the correlation coefficient (r), P, and sample size (N) are displayed in the box. Model 1 was adjusted for age, sex, study center, and population structure and pedigree, and model 2 was further adjusted for BMI, smoking, physical activity, drinking, estrogen-therapy use, lipid-lowering medication use, education level, total energy intake, dietary total fat, total folate, and vitamin B-12, and glycemic load (or glycemic index or whole-grain intake). The methylation analysis in the GOLDN study was adjusted for age, sex, study center, pedigree, and principal components for cellular purity. ABCA1, ATP-binding cassette subfamily A member 1; ARIC, Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities; CHARGE, Cohorts for Heart and Aging Research in Genomic Epidemiology; CHS, Cardiovascular Health Study; GOLDN, Genetics of Lipid Lowering Drugs and Diet Network; InCHIANTI, Invecchiare in Chianti; MESA, Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphisms; WGHS, Women’s Genome Health Study; 3C, Three-City Study.

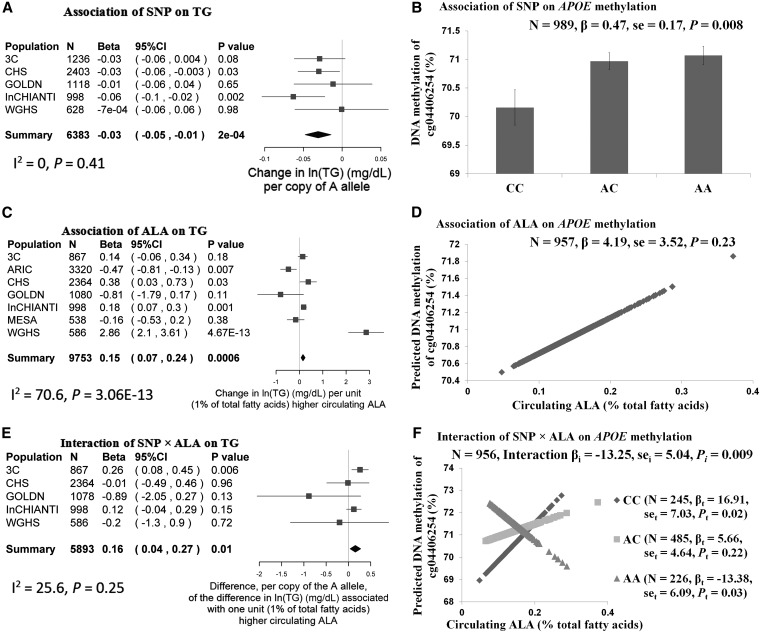

At APOE, we showed that the A allele of APOE rs405509 was associated with a lower ln of the geometric mean of triglycerides [β = −0.03 ln(mg/dL) per A allele, P = 0.0002 in model 1] (Figure 3A). A higher mean ALA (percentage of total circulating fatty acids) was also associated with a greater ln of the geometric mean of plasma triglycerides [β = 0.15 ln(mg/dL) per 1% higher ALA, P = 0.0006 in model 2] (Figure 3C). In addition, the difference in the ln of the geometric mean of plasma triglycerides associated with 1% higher circulating ALA was dependent on the genotype at rs405509 (P = 0.01); we estimated that this difference was 0.16 ln(mg/dL) higher for each additional A allele (Figure 3E). Additional adjustment for dietary fiber, waist circumference, and other types of methyl donors with the use of the GOLDN study dataset did not appreciably change the results.

FIGURE 3 .

Relations in plasma TG, ALA, and SNP, DNA methylation, and gene expression at the APOE locus. Main effects of APOE rs405509 on the outcome of TG (model 1) and methylation of APOE cg04406254 are presented in a forest plot with a meta-analysis in the CHARGE consortium (A) and bar charts by genotype in the GOLDN study (B), respectively. Main effects of circulating ALA on the outcome of TG (model 2) and methylation of APOE cg04406254 are presented in a forest plot with a meta-analysis in the CHARGE consortium (C) and bar charts by genotype in the GOLDN study (D), respectively. Interactions of rs405509 × ALA on the outcome of TG (model 2) and methylation of APOE cg405509 are presented in a forest plot with a meta-analysis in the CHARGE consortium (E) and a plot with genotype-dependent regression lines in the GOLDN study (F), respectively. In forest plots, the estimated β and its 95% CI, which illustrated the changes in plasma ln(TG) per copy of the rs405509 A allele in panel A, the changes in plasma ln(TG) per unit (percentage of total fatty acid) of higher circulating ALA in panel C, and the association with each 1% higher percentage of circulating ALA with ln(TG) per copy of the rs405509 A allele in panel E, respectively, are represented by the filled square and horizontal line for each population or the filled diamond for the summary. In panel F, βi, sei, and Pi represent the regression coefficient, SE, and corresponding significance for the interaction term, respectively, which were interpreted as the association of each 1% higher percentage of circulating ALA with methylation of cg04406254 per copy of the rs405509 A allele, whereas βt, set, and Pt represent the regression coefficient, SE, and significance for a trend, respectively, which were interpreted as the association of circulating ALA with cg04406254 methylation according to 3 genotype groups of rs405509 (AA, AC, and CC). Model 1 was adjusted for age, sex, study center, and population structure and pedigree, and model 2 was further adjusted for BMI, smoking, physical activity, drinking, estrogen therapy use, lipid-lowering medication use, education level, total energy intake, dietary total fat, total folate, and vitamin B-12, and glycemic load (or glycemic index or whole-grain intake). The methylation analysis in the GOLDN study was adjusted for age, sex, study center, pedigree, and principal components for cellular purity (only for the methylation analysis). ALA, α-linolenic acid; APOE, apolipoprotein E; ARIC, Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities; CHS, Cardiovascular Health Study; GOLDN, Genetics of Lipid Lowering Drugs and Diet Network; InCHIANTI, Invecchiare in Chianti; MESA, Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphisms; TG, triglycerides; WGHS, Women’s Genome Health Study; 3C, Three-City Study.

Association analyses on methylation as an outcome in the GOLDN study

At ABCA1, we observed that the C allele of ABCA1 rs2246293 was associated with a higher mean methylation of ABCA1 cg14019050 (β = 8.84% per C allele, P = 3.51 × 1018) (Figure 2B). Higher mean circulating EPA (percentage of total circulating fatty acids) was associated with lower methylation of cg14019050 (β = −1.46% per 1% higher EPA, P = 0.009) (Figure 2D). Also, the mean difference in cg14019050 methylation associated with 1% higher circulating EPA was dependent on the genotype at rs2246293 (P = 0.007); we estimated that this difference was 2.83% lower for each additional C allele (Figure 2F).

At APOE, we showed that the A allele of APOE rs405509 was associated with higher a higher mean methylation of APOE cg04406254 (β = 0.47% per A allele, P = 0.008) (Figure 3B). The mean difference in cg04406254 methylation associated with 1% higher circulating ALA was dependent on the genotype at rs405509 (P = 0.009), and the estimated difference was 13.25% lower for each additional A allele (Figure 3F). But there was no significant association between mean circulating ALA (percentage of total fatty acids) and cg04406254 methylation (percentage) (P = 0.23) (Figure 3D).

Correlation analyses with data in the GOLDN study and ENCODE consortium

At ABCA1, we further showed that methylation of ABCA1 cg14019050 was negatively correlated with plasma HDL cholesterol (r = −0.12, P = 0.0002) (Figure 2G) as well as with the gene expression of ABCA1 (r = −0.61, P = 0.009) (Figure 2H).

Mediation analyses in the GOLDN study, CHS, and MESA

To explore whether DNA methylation of the CpG site at ABCA1 and APOE loci might have acted as a mediator for the observed gene-by–fatty acid associations and interactions on plasma lipids, we conducted a mediation analysis with the use of meta-analysis approach in the GOLDN study, CHS, and MESA. We applied the following 2 statistical criteria to test whether methylation acts as a mediator of a statistical association or interaction relation: 1) that the addition of the potential mediator (methylation percentage of ABCA1 cg14019050 or APOE cg04406254) to the original regression model reduces the magnitude of the regression coefficients of the SNP, fatty acid, and their interaction term (SNP × fatty acid) and 2) that the differences in these regression coefficients before and after addition of the potential mediator as evaluated with the use of a bootstrap analysis was significant (P < 0.05).

According to the first criterion (Table 2), the magnitude of the regression coefficients for variables of ABCA1 rs2246293, EPA, and the interaction term of rs2246293 × EPA in the models with the adjustment of ABCA1 cg14019050 methylation were smaller than those obtained in the models without adjustment. However, at APOE, only the interaction term of rs405509 × ALA had a smaller regression coefficient in the model with the adjustment of APOE cg04406254 methylation than in the model without such adjustment (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Mediation analysis of meta-analyzed changes in regression coefficients between 2 nested models on plasma lipids in the GOLDN study (22), CHS (21), and MESA (24)1

| Outcome | Gene | Variable | Model | n | β ± SE | P | Direction | Heterogeneity I2 | Heterogeneity P |

| HDL, mg/dL | ABCA1 | rs22462932 | Without cg14019050 | 1576 | −0.79 ± 0.50 | 0.12 | −−− | 0 | 0.94 |

| With cg14019050 | 1472 | −0.73 ± 0.67 | 0.28 | −+− | 0 | 0.53 | |||

| EPA | Without cg14019050 | 1825 | 2.57 ± 0.72 | 0.0003 | +++ | 46.3 | 0.16 | ||

| With cg14019050 | 1700 | 2.53 ± 0.72 | 0.0005 | +++ | 48.3 | 0.14 | |||

| rs2246293 × EPA | Without cg14019050 | 1534 | 1.502 ± 1.07 | 0.16 | +−+ | 0 | 0.46 | ||

| With cg14019050 | 1432 | 1.495 ± 1.07 | 0.16 | +−+ | 0 | 0.44 | |||

| ln(Triglycerides), mg/dL | APOE | rs4055092 | Without cg04406254 | 1875 | −0.019 ± 0.02 | 0.33 | −−− | 0 | 0.87 |

| With cg04406254 | 1748 | −0.024 ± 0.02 | 0.22 | −−− | 0 | 0.94 | |||

| ALA | Without cg04406254 | 1827 | −0.14 ± 0.18 | 0.44 | −−+ | 69.3 | 0.04 | ||

| With cg04406254 | 1702 | −0.16 ± 0.18 | 0.37 | −−+ | 74.5 | 0.02 | |||

| rs405509 × ALA | Without cg04406254 | 1824 | 0.04 ± 0.32 | 0.90 | −++ | 66.3 | 0.05 | ||

| With cg04406254 | 1700 | 0.002 ± 0.31 | 0.99 | −++ | 71 | 0.03 |

β ± SE and P represent the regression coefficient ± SE and the significance, respectively, of the expected changes in plasma HDL cholesterol or ln(triglycerides) per unit change in the corresponding variable, and the common covariates for the 2 nested models were age, sex, study center, pedigree or population structure, and white cell proportion (if applicable). Direction represents the sign of the regression coefficient of expected changes in plasma HDL cholesterol or ln(triglycerides) per unit change in the corresponding variable in the GOLDN study, CHS, and MESA, respectively. Heterogeneity I2 and heterogeneity P represent the estimated heterogeneity I2 value and its corresponding significance, respectively, for the meta-analysis of the regression coefficient of the expected changes in plasma HDL cholesterol or ln(triglycerides) per unit change in the corresponding variable across the GOLDN study, CHS, and MESA. ABCA1, ATP-binding cassette subfamily A member 1; ALA, α-linolenic acid; APOE, apolipoprotein E; CHS, Cardiovascular Health Study; GOLDN, Genetics of Lipid Lowering Drugs and Diet Network; MESA, Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis.

Coded alleles of ABCA1 rs2246293 and APOE rs405509 are C and A alleles, respectively.

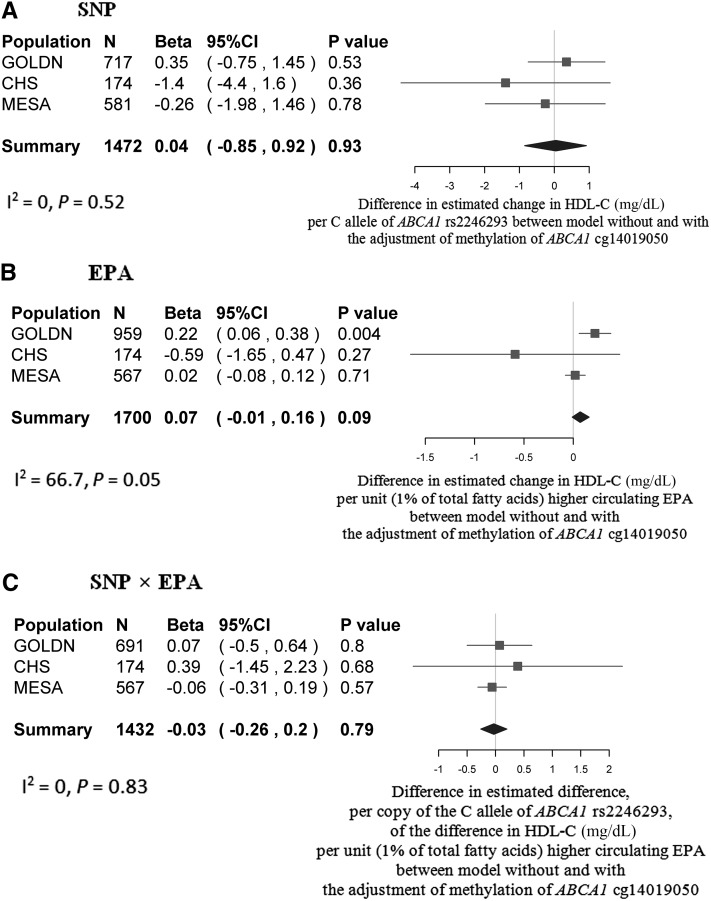

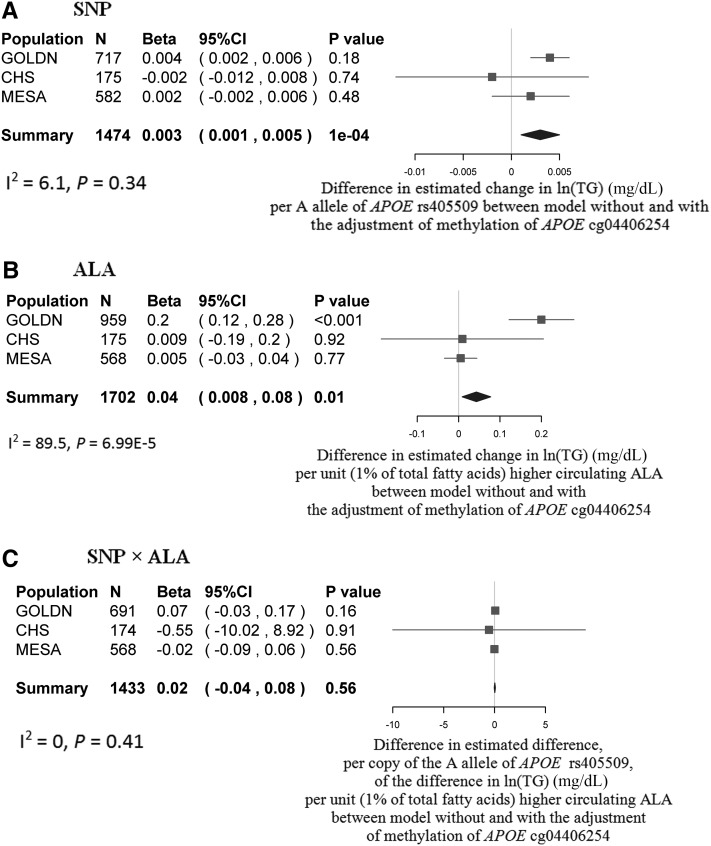

According to the second criterion of the bootstrap analysis, at ABCA1 (Figure 4), only the difference in the regression coefficient for circulating EPA (percentage of total fatty acids) between 2 nested models was significant in the GOLDN study (P = 0.004) but not in the CHS (P = 0.27) or the MESA (P = 0.71). The significant difference shown in the GOLDN study was attenuated in the meta-analysis across 3 studies (P = 0.09). At APOE (Figure 5), differences in the regression coefficients for both SNP rs405509 and circulating ALA (percentage of total fatty acids) between the 2 nested models were significant (P = 0.0001 and P = 0.01, respectively).

FIGURE 4 .

Mediation analysis of meta-analyzed bootstrap results at ABCA1 in the GOLDN study (22), CHS (21), and MESA (24). Bootstrap analyses of the differences in regression coefficients of SNP (rs2246293) (A), circulating EPA (B), and their interaction term of SNP × EPA (C) between 2 models without and with the adjustment of methylation at ABCA1 cg14019050 are represented by forest plots with meta-analyses across the GOLDN study, CHS, and MESA. The filled square and horizontal line for each population and the filled diamond for the summary represent the estimated differences in the regression coefficient between 2 nested models and its 95% CI. Panel A shows the differences in regression coefficients, which, themselves, represent the mean change in HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) per C allele of ABCA1 rs2246293. Panel B shows the differences in the regression coefficients, which themselves represent the mean change in HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) per unit (1% of total fatty acids) of higher circulating EPA. Panel C shows differences in the interaction coefficients, which, themselves, represent the difference, per copy of the C allele, of the difference in HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) per unit (1% of total fatty acids) of higher circulating EPA. The common covariates adjusted in the models included age, sex, study center (if applicable), pedigree or population structure, and white cell proportion (if applicable). ABCA1, ATP-binding cassette subfamily A member 1; CHS, Cardiovascular Health Study; HDL-C, HDL cholesterol; GOLDN, Genetics of Lipid Lowering Drugs and Diet Network; MESA, Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphisms.

FIGURE 5 .

Mediation analysis of meta-analyzed bootstrap results at APOE in the GOLDN study (22), CHS (21), and MESA (24). Bootstrap analyses of the differences in regression coefficients of SNP (rs405509) (A), circulating ALA (B), and their interaction term of SNP × ALA (C) between 2 models without and with the adjustment of methylation at APOE cg04406254 are represented by forest plots with meta-analyses across the GOLDN study, CHS, and MESA. The filled square and horizontal line for each population and the filled diamond for the summary represent the estimated differences in the regression coefficient between 2 nested models and its 95% CI. Panel A shows the differences in regression coefficients, which, themselves, represent the mean change in ln(TG) (mg/dL) per A allele of APOE rs405509. Panel B shows the differences in regression coefficients, which, themselves, represent the mean change in ln(TG) (mg/dL) per unit (1% of total fatty acids) of higher circulating ALA. Panel C shows the differences in interaction coefficients, which, themselves, represent the difference, per copy of the A allele, of the difference in ln(TG) (mg/dL) per unit (1% of total fatty acids) of higher circulating ALA. Common covariates adjusted for in the models included age, sex, study center (if applicable), pedigree or population structure, and white cell proportion (if applicable). ALA, α-linolenic acid; APOE, apolipoprotein E; CHS, Cardiovascular Health Study; GOLDN, Genetics of Lipid Lowering Drugs and Diet Network; MESA, Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphisms; TG, triglycerides.

With consideration of both criteria of the mediation analysis, there was little evidence that the methylation of ABCA1 cg14019050 (percentage) acted as a mediator for the association between EPA and HDL cholesterol or the association between the rs2246293 C allele and HDL cholesterol or that the cg14019050 methylation mediated rs2246293 genotype-related differences in the EPA–HDL-cholesterol association. None of the tests at APOE met both criteria for mediation.

DISCUSSION

We applied a novel integrated approach that incorporated a meta-analysis of genetic interactions, evaluations of DNA methylation data, and gene-expression data to investigate mechanisms by which genetic variants interact with fatty acids for plasma lipid outcomes, which provided preliminary mechanistic evidence to support more personalized nutrition. For example, individuals with specific sequence variants may benefit from higher circulating EPA. Moreover, knowledge of the genotype and methylation status of biologically relevant loci (e.g., ABCA1) may suggest a potential mechanism by which dietary EPA mediates a more-favorable lipid profile in some individuals according to genotype. Although we obtained little evidence that DNA methylation acted as the mediator of the observed gene–fatty acid interaction, we showed that the mean difference in HDL cholesterol associated with higher circulating EPA depended on genotypes of ABCA1 rs2246293, which suggested that individuals with specific sequence variants may benefit from higher circulating EPA.

Our findings that illustrated possible connections between circulating EPA, genetic variation, DNA methylation, and gene expression of ABCA1 and plasma HDL cholesterol were not only consistent with those of a previous study (7) but also consistent with the biological function of ABCA1. ABCA1 encodes a membrane transporter that is involved in the reverse cholesterol transport pathway by promoting an efflux of free cholesterol and phospholipids to form HDL-cholesterol particles (43). Our group and other authors showed that loss-of-function mutations in ABCA1 contribute to the cause of Tangier disease, which is a disease characterized by an extremely low amount or even absence of HDL cholesterol (44–46). Cg14019050, which is the CpG site on which our current data were based, is located within the promoter region of ABCA1. In previous studies, plasma HDL cholesterol was negatively correlated with methylation of the ABCA1 promoter in familial hypercholesterolemia (7). On the basis of previous findings and our observations of the consistent association results for the outcome of HDL cholesterol and ABCA1-promoter methylation, we had hypothesized that EPA decreases ABCA1 promoter methylation, which leads to an increase in the gene expression of ABCA1 and a corresponding increase in plasma HDL cholesterol and that this proposed sequence of events may be genotype-dependent. However, we obtained little evidence that ABCA1 methylation acted as a mediator of the genotype-dependent differences in the effect of EPA on plasma HDL cholesterol. Although our findings in the GOLDN study suggested that ABCA1 methylation may have acted as a mediator of the effect of EPA on plasma HDL cholesterol, this result was attenuated by adding the CHS and MESA into the analyses. Taken together, our analyses indicate that the relations in the factors of circulating EPA, ABCA1-promoter methylation, ABCA1-promoter variant, and plasma HDL cholesterol are complex and may not act through a direct pathway.

Our findings at APOE were consistent with those of a previous article that the methylation percentage of APOE cg04406254 tended to be negatively associated with plasma triglycerides in the GOLDN study and was also negatively correlated with APOE gene expression in the ENCODE consortium (40).

Several limitations must be described. Our study was limited by the cross-sectional study design from which associations but not cause-effect relations could be concluded. From the perspective of significance, although we already selected SNPs with minor allele frequency >1%, the study may still have been underpowered to detect significant interactions after strict Bonferroni corrections for multiple testing because very large samples were required to have adequate power to detect an interaction (47). However, the consistency of our findings for plasma lipids and DNA methylation provided possible biological support for those interactions that reached a nominal significance level. In addition, not all studies that contributed data to this analysis measured fatty acids in the same compartment (e.g., plasma compared with erythrocyte membrane), which may also have introduced variability that could have attenuated the potential significance of the interaction relations. The heterogeneity of the mean effects of circulating fatty acids on plasma lipids was significant, which may have been related to differences in the concentrations of circulating fatty acids that were measured in different compartments (48). Our findings can be generalized to Caucasian populations with similar ranges of fatty acids. Also, we did not consider the effects of SNPs or genes on circulating fatty acids in the SNP-selection step because the fatty acids were the exposures and not the outcomes. However, this neglect may have prevented us from observing the potential gene-gene interactions. In addition, the replication in the CHS and MESA may not have had enough statistical power because of their small sample sizes or heterogeneities in their usages of tissues to measure methylation. Some of the fatty acids are biomarkers of intake, whereas others are biomarkers of metabolism, and thus, additional work is needed with dietary fatty acids for confirmation. Also, the restricted selection of CpG sites within the promoter regions may have missed the potential regulatory elements outside the genes although methylation in the promoter regions was more likely to have affected gene expression (49).

In conclusion, the current study obtained little evidence to support the hypothesis that gene-by–fatty acid interactions on plasma lipids are mediated by DNA methylation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Data for the “Building on GWAS for NHLBI-diseases: the U.S. CHARGE Consortium” was provided by Eric Boerwinkle (on behalf of the ARIC study), L Adrienne Cupples (principal investigator for the Framingham Heart Study), and Bruce Psaty (principal investigator for the CHS).

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—YM: contributed to the study design, genotyping, data analysis within the GOLDN study, meta-analysis, interpretation of the results, and manuscript writing; JLF: contributed to the meta-analysis; CES: contributed to the study design, interpretation of the results, and manuscript writing; TT: contributed to the data analysis in the InCHIANTI cohort, interpretation of the results, and manuscript editing; AWM: contributed to the data analysis in the MESA cohort, interpretation of the results, and manuscript editing; AYC: contributed to the data analysis in the Women’s Genome Health Study and to the manuscript editing; CS: contributed to the data analysis in Three-City Study and to the manuscript editing; XZ: contributed to the data analysis in the ARIC study and to the manuscript editing; WG and DSS: contributed to the interpretation of the results and to the manuscript editing; LW, Y-DIC, DGH, IB, DIC, SSR, LF, MRI, SA, DZ, HKT, SAC, JS, EKK, C-QL, LDP, Y-CL, PA, J-CL, BMP, IBK, DM, BM, SB, MYT, PMR, JD, KLM, P-BG, and LMS: contributed to the manuscript editing; MLB: contributed to the replication of the methylation analysis in the CHS; DM: was the primary investigator for fatty acids measurements of the CHS population; YL, NS, and DA: were the primary investigators for the methylation measurements in the GOLDN study, CHS, and MESA, respectively; DKA: was the primary investigator for the phenotyping of the GOLDN study population; JMO: was the primary investigator for the genotyping of the GOLDN study; RNL: contributed to the study design, interpretation of the results, and manuscript writing. None of the authors reported a conflict of interest related to the study.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used: AA, arachidonic acid; ABCA1, ATP-binding cassette subfamily A member 1; ALA, α-linolenic acid; APOE, apolipoprotein E; ARIC, Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities; CHARGE, Cohorts for Heart and Aging Research in Genomic Epidemiology; CHS, Cardiovascular Health Study; CpG, cytosine-phosphate-guanine; ENCODE, Encyclopedia of DNA Elements; GOLDN, Genetics of Lipid Lowering Drugs and Diet Network; InCHIANTI, Invecchiare in Chianti; LA, linoleic acid; MESA, Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis; OA, oleic acid; PA, palmitic acid; PPARGC1A, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma, coactivator 1, alpha; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; 3C, Three-City Study.

REFERENCES

- 1.McCabe MT, Brandes JC, Vertino PM. Cancer DNA methylation: molecular mechanisms and clinical implications. Clin Cancer Res 2009;15:3927–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dong C, Yoon W, Goldschmidt-Clermont PJ. DNA methylation and atherosclerosis. J Nutr 2002;132(8 Suppl):2406S–9S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gemma C, Sookoian S, Alvarinas J, Garcia SI, Quintana L, Kanevsky D, Gonzalez CD, Pirola CJ. Maternal pregestational BMI is associated with methylation of the PPARGC1A promoter in newborns. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009;17:1032–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nile CJ, Read RC, Akil M, Duff GW, Wilson AG. Methylation status of a single CpG site in the IL6 promoter is related to IL6 messenger RNA levels and rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2008;58:2686–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Jager PL, Srivastava G, Lunnon K, Burgess J, Schalkwyk LC, Yu L, Eaton ML, Keenan BT, Ernst J, McCabe C, et al. Alzheimer’s disease: early alterations in brain DNA methylation at ANK1, BIN1, RHBDF2 and other loci. Nat Neurosci 2014;17:1156–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greenhill C. Diabetes: DNA methylation affects T2DM risk. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2015;11:505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guay SP, Brisson D, Munger J, Lamarche B, Gaudet D, Bouchard L. ABCA1 gene promoter DNA methylation is associated with HDL particle profile and coronary artery disease in familial hypercholesterolemia. Epigenetics 2012;7:464–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hellman A, Chess A. Gene body-specific methylation on the active X chromosome. Science 2007;315:1141–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Devlin AM, Singh R, Wade RE, Innis SM, Bottiglieri T, Lentz SR. Hypermethylation of Fads2 and altered hepatic fatty acid and phospholipid metabolism in mice with hyperhomocysteinemia. J Biol Chem 2007;282:37082–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barrès R, Osler ME, Yan J, Rune A, Fritz T, Caidahl K, Krook A, Zierath JR. Non-CpG methylation of the PGC-1alpha promoter through DNMT3B controls mitochondrial density. Cell Metab 2009;10:189–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ceccarelli V, Racanicchi S, Martelli MP, Nocentini G, Fettucciari K, Riccardi C, Marconi P, Di Nardo P, Grignani F, Binaglia L, et al. Eicosapentaenoic acid demethylates a single CpG that mediates expression of tumor suppressor CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein delta in U937 leukemia cells. J Biol Chem 2011;286:27092–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lienert F, Wirbelauer C, Som I, Dean A, Mohn F, Schubeler D. Identification of genetic elements that autonomously determine DNA methylation states. Nat Genet 2011;43:1091–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bell CG, Finer S, Lindgren CM, Wilson GA, Rakyan VK, Teschendorff AE, Akan P, Stupka E, Down TA, Prokopenko I, et al. Integrated genetic and epigenetic analysis identifies haplotype-specific methylation in the FTO type 2 diabetes and obesity susceptibility locus. PLoS One 2010;5:e14040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gertz J, Varley KE, Reddy TE, Bowling KM, Pauli F, Parker SL, Kucera KS, Willard HF, Myers RM. Analysis of DNA methylation in a three-generation family reveals widespread genetic influence on epigenetic regulation. PLoS Genet 2011;7:e1002228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qu W, Hashimoto S, Shimada A, Nakatani Y, Ichikawa K, Saito TL, Ogoshi K, Matsushima K, Suzuki Y, Sugano S, et al. Genome-wide genetic variations are highly correlated with proximal DNA methylation patterns. Genome Res 2012;22:1419–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shoemaker R, Deng J, Wang W, Zhang K. Allele-specific methylation is prevalent and is contributed by CpG-SNPs in the human genome. Genome Res 2010;20:883–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang D, Cheng L, Badner JA, Chen C, Chen Q, Luo W, Craig DW, Redman M, Gershon ES, Liu C. Genetic control of individual differences in gene-specific methylation in human brain. Am J Hum Genet 2010;86:411–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gibbs JR, van der Brug MP, Hernandez DG, Traynor BJ, Nalls MA, Lai SL, Arepalli S, Dillman A, Rafferty IP, Troncoso J, et al. Abundant quantitative trait loci exist for DNA methylation and gene expression in human brain. PLoS Genet 2010;6:e1000952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.3C Study Group. Vascular factors and risk of dementia: design of the Three-City Study and baseline characteristics of the study population. Neuroepidemiology 2003;22:316–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study: design and objectives. The ARIC investigators. Am J Epidemiol 1989;129:687–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fried LP, Borhani NO, Enright P, Furberg CD, Gardin JM, Kronmal RA, Kuller LH, Manolio TA, Mittelmark MB, Newman A, et al. The Cardiovascular Health Study: design and rationale. Ann Epidemiol 1991;1:263–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Corella D, Arnett DK, Tsai MY, Kabagambe EK, Peacock JM, Hixson JE, Straka RJ, Province M, Lai CQ, Parnell LD, et al. The -256T>C polymorphism in the apolipoprotein A-II gene promoter is associated with body mass index and food intake in the genetics of lipid lowering drugs and diet network study. Clin Chem 2007;53:1144–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferrucci L, Bandinelli S, Benvenuti E, Di Iorio A, Macchi C, Harris TB, Guralnik JM. Subsystems contributing to the decline in ability to walk: bridging the gap between epidemiology and geriatric practice in the InCHIANTI study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2000;48:1618–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bild DE, Bluemke DA, Burke GL, Detrano R, Diez Roux AV, Folsom AR, Greenland P, Jacob DR Jr, Kronmal R, Liu K, et al. Multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis: objectives and design. Am J Epidemiol 2002;156:871–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ridker PM, Chasman DI, Zee RY, Parker A, Rose L, Cook NR, Buring JE,Women's Genome Health Study Working Group. Rationale, design, and methodology of the Women’s Genome Health Study: a genome-wide association study of more than 25,000 initially healthy american women. Clin Chem 2008;54:249–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Podvinec M, Kaufmann MR, Handschin C, Meyer UA. NUBIScan, an in silico approach for prediction of nuclear receptor response elements. Mol Endocrinol 2002;16:1269–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meissner A, Mikkelsen TS, Gu H, Wernig M, Hanna J, Sivachenko A, Zhang X, Bernstein BE, Nusbaum C, Jaffe DB, et al. Genome-scale DNA methylation maps of pluripotent and differentiated cells. Nature 2008;454:766–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ernst J, Kheradpour P, Mikkelsen TS, Shoresh N, Ward LD, Epstein CB, Zhang X, Wang L, Issner R, Coyne M, et al. Mapping and analysis of chromatin state dynamics in nine human cell types. Nature 2011;473:43–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aulchenko YS, Ripatti S, Lindqvist I, Boomsma D, Heid IM, Pramstaller PP, Penninx BW, Janssens AC, Wilson JF, Spector T, et al. Loci influencing lipid levels and coronary heart disease risk in 16 European population cohorts. Nat Genet 2009;41:47–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Teslovich TM, Musunuru K, Smith AV, Edmondson AC, Stylianou IM, Koseki M, Pirruccello JP, Ripatti S, Chasman DI, Willer CJ, et al. Biological, clinical and population relevance of 95 loci for blood lipids. Nature 2010;466:707–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wallace C, Newhouse SJ, Braund P, Zhang F, Tobin M, Falchi M, Ahmadi K, Dobson RJ, Marcano AC, Hajat C, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies genes for biomarkers of cardiovascular disease: serum urate and dyslipidemia. Am J Hum Genet 2008;82:139–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Willer CJ, Sanna S, Jackson AU, Scuteri A, Bonnycastle LL, Clarke R, Heath SC, Timpson NJ, Najjar SS, Stringham HM, et al. Newly identified loci that influence lipid concentrations and risk of coronary artery disease. Nat Genet 2008;40:161–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kathiresan S, Willer CJ, Peloso GM, Demissie S, Musunuru K, Schadt EE, Kaplan L, Bennett D, Li Y, Tanaka T, et al. Common variants at 30 loci contribute to polygenic dyslipidemia. Nat Genet 2009;41:56–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Diabetes Genetics Initiative of Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT, Lund University, and Novartis Institutes of BioMedical Research, Saxena R, Voight BF, Lyssenko V, Burtt NP, de Bakker PI, Chen H, Roix JJ, Kathiresan S, Hirschhorn JN, et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies loci for type 2 diabetes and triglyceride levels. Science 2007;316:1331–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Ridker PM, Pare G, Parker AN, Zee RY, Miletich JP, Chasman DI. Polymorphism in the CETP gene region, HDL cholesterol, and risk of future myocardial infarction: Genomewide analysis among 18 245 initially healthy women from the Women’s Genome Health Study. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2009;2:26–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sandhu MS, Waterworth DM, Debenham SL, Wheeler E, Papadakis K, Zhao JH, Song K, Yuan X, Johnson T, Ashford S, et al. LDL-cholesterol concentrations: a genome-wide association study. Lancet 2008;371:483–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Irvin MR, Zhi D, Joehanes R, Mendelson M, Aslibekyan S, Claas SA, Thibeault KS, Patel N, Day K, Jones LW, et al. Epigenome-wide association study of fasting blood lipids in the Genetics of Lipid-lowering Drugs and Diet Network study. Circulation 2014;130:565–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leek JT, Storey JD. Capturing heterogeneity in gene expression studies by surrogate variable analysis. PLoS Genet 2007;3:1724–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ding J, Reynolds LM, Zeller T, Muller C, Mstat KL, Nicklas BJ, Kritchevsky SB, Huang Z, Fuente A, Soranzo N, et al. Alterations of a cellular cholesterol metabolism network is a molecular feature of obesity-related type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Diabetes 2015;64:3464–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Naj AC, Jun G, Reitz C, Kunkle BW, Perry W, Park YS, Beecham GW, Rajbhandary RA, Hamilton-Nelson KL, Wang LS, et al. Effects of multiple genetic Loci on age at onset in late-onset Alzheimer disease: a genome-wide association study. JAMA Neurol 2014;71:1394–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Willer CJ, Li Y, Abecasis GR. METAL: fast and efficient meta-analysis of genomewide association scans. Bioinformatics 2010;26:2190–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Efron BTR. An introduction to the bootstrap. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tall AR, Yvan-Charvet L, Terasaka N, Pagler T, Wang N. HDL, ABC transporters, and cholesterol efflux: implications for the treatment of atherosclerosis. Cell Metab 2008;7:365–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rust S, Walter M, Funke H, von Eckardstein A, Cullen P, Kroes HY, Hordijk R, Geisel J, Kastelein J, Molhuizen HO, et al. Assignment of Tangier disease to chromosome 9q31 by a graphical linkage exclusion strategy. Nat Genet 1998;20:96–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brooks-Wilson A, Marcil M, Clee SM, Zhang LH, Roomp K, van Dam M, Yu L, Brewer C, Collins JA, Molhuizen HO, et al. Mutations in ABC1 in Tangier disease and familial high-density lipoprotein deficiency. Nat Genet 1999;22:336–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brousseau ME, Schaefer EJ, Dupuis J, Eustace B, Van Eerdewegh P, Goldkamp AL, Thurston LM, FitzGerald MG, Yasek-McKenna D, O’Neill G, et al. Novel mutations in the gene encoding ATP-binding cassette 1 in four tangier disease kindreds. J Lipid Res 2000;41:433–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nettleton JA, McKeown NM, Kanoni S, Lemaitre RN, Hivert MF, Ngwa J, van Rooij FJ, Sonestedt E, Wojczynski MK, Ye Z, et al. Interactions of dietary whole-grain intake with fasting glucose- and insulin-related genetic loci in individuals of European descent: a meta-analysis of 14 cohort studies. Diabetes Care 2010;33:2684–91. Erratum in: Diabetes Care 2011;34:785–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smith CE, Follis JL, Nettleton JA, Foy M, Wu JH, Ma Y, Tanaka T, Manichakul AW, Wu H, Chu AY, et al. Dietary fatty acids modulate associations between genetic variants and circulating fatty acids in plasma and erythrocyte membranes: meta-analysis of nine studies in the CHARGE consortium. Mol Nutr Food Res 2015;59:1373–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Irizarry RA, Ladd-Acosta C, Wen B, Wu Z, Montano C, Onyango P, Cui H, Gabo K, Rongione M, Webster M, et al. The human colon cancer methylome shows similar hypo- and hypermethylation at conserved tissue-specific CpG island shores. Nat Genet 2009;41:178–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.