Abstract

STUDY QUESTION

What are the respective roles of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), long-term weight gain and obesity for the development of prediabetes or Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) by age 46 years?

SUMMARY ANSWER

The risk of T2DM in women with PCOS is mainly due to overweight and obesity, although these two factors have a synergistic effect on the development of T2DM.

WHAT IS KNOWN ALREADY

PCOS is associated with an increased risk of prediabetes and T2DM. However, the respective roles of PCOS per se and BMI for the development of T2DM have remained unclear.

STUDY DESIGN, SIZE, DURATION

In a prospective, general population-based follow-up birth cohort 1966 (n = 5889), postal questionnaires were sent at ages 14 (95% answered), 31 (80% answered) and 46 years (72% answered). Questions about oligoamenorrhoea and hirsutism were asked at age 31 years, and a question about PCOS diagnosis at 46 years. Clinical examination and blood sampling were performed at 31 years in 3127 women, and at 46 years in 3280 women. A 2-h oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) was performed at 46 years of age in 2780 women.

PARTICIPANTS/MATERIALS, SETTING, METHODS

Women reporting both oligoamenorrhoea and hirsutism at age 31 years and/or diagnosis of PCOS by 46 years were considered as women with PCOS (n = 279). Women without any symptoms at 31 years and without PCOS diagnosis by 46 years were considered as controls (n = 1577). The level of glucose metabolism was classified according to the results of the OGTT and previous information of glucose metabolism status from the national drug and hospital discharge registers.

MAIN RESULTS AND THE ROLE OF CHANCE

PCOS per se significantly increased the risk of T2DM in overweight/obese (BMI ≥ 25.0 kg/m2) women with PCOS when compared to overweight/obese controls (odds ratio: 2.45, 95% CI: 1.28–4.67). Normal weight women with PCOS did not present with an increased risk of prediabetes or T2DM. The increase in weight between ages 14, 31 and 46 years was significantly greater in women with PCOS developing T2DM than in women with PCOS and normal glucose tolerance, with the most significant increase occurring in early adulthood (between 14 and 31 years: median with [25%; 75% quartiles]: 27.25 kg [20.43; 34.78] versus 13.80 kg [8.55; 20.20], P < 0.001).

LIMITATIONS, REASONS FOR CAUTION

The diagnosis of PCOS was based on self-reporting, and the questionnaire at 46 years did not distinguish between polycystic ovaries only in ultrasonography and the syndrome. Ovarian ultrasonography was not available to aid the diagnosis of PCOS.

WIDER IMPLICATIONS OF THE FINDINGS

These results emphasize weight management already during adolescence and early adulthood to prevent the development of T2DM in women with PCOS, as the period between 14 and 31 years seems to be a crucial time-window during which the women with PCOS who are destined to develop T2DM by 46 years of age experience a dramatic weight gain. Furthermore, our results support the view that, particularly in times of limited sources of healthcare systems, OGTT screening should be targeted to overweight/obese women with PCOS rather than to all women with PCOS.

STUDY FUNDING/COMPETING INTEREST(S)

Finnish Medical Foundation; North Ostrobothnia Regional Fund; Academy of Finland (project grants 104781, 120315, 129269, 1114194, 24300796, Center of Excellence in Complex Disease Genetics and SALVE); Sigrid Juselius Foundation; Biocenter Oulu; University Hospital Oulu and University of Oulu (75617); Medical Research Center Oulu; National Institute for Health Research (UK); National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (grant 5R01HL087679-02) through the STAMPEED program (1RL1MH083268-01); National Institute of Health/National Institute of Mental Health (5R01MH63706:02); ENGAGE project and grant agreement HEALTH-F4-2007–201413; EU FP7 EurHEALTHAgeing-277849 European Commission and Medical Research Council, UK (G0500539, G0600705, G1002319, PrevMetSyn/SALVE) and Medical Research Center, Centenary Early Career Award. The authors have no conflicts of interests.

TRIAL REGISTRATION NUMBER

N/A.

Keywords: Polycystic ovary syndrome, prediabetes, Type 2 diabetes mellitus, BMI, weight gain

Introduction

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a heterogeneous entity and is characterized not only by reproductive disturbances, such as anovulatory infertility and pregnancy complications but also by increased risk of disorders of glucose metabolism and increased markers of cardiovascular morbidity (Franks, 1995; Fauser et al., 2012). Hyperandrogenism and insulin resistance are characteristic features of the syndrome, and compensatory hyperinsulinaemia, that accompanies insulin resistance, augments androgen production (Baptiste et al., 2010).

There is evidence that insulin resistance in PCOS arises, at least in part, from an intrinsic defect in post-receptor insulin signalling in its classical target tissues, such as muscle cells and adipocytes (Diamanti-Kandarakis and Papavassiliou, 2006). Moreover, women with PCOS also commonly present with overweight and obesity, particularly visceral obesity (Gambineri et al., 2012), which promotes insulin resistance. Results of a recent meta-analysis confirm the well-reported association of PCOS with increased risk of prediabetes (impaired fasting glucose [IFG] or impaired glucose tolerance [IGT]) and Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) (Moran et al., 2010). However, the results of studies regarding the roles and interactions of weight, weight gain, hyperandrogaenism and the syndrome per se on the development of prediabetes and T2DM have been inconsistent. Some studies have suggested that PCOS per se increases the risk of prediabetes and T2DM independent of BMI (Legro et al., 1999; Moran et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2011; Joham et al., 2014), whereas others have linked the risk only with obesity (Norman et al., 2001; Boudreaux et al., 2006; Espinos-Gomez et al., 2009; Gambineri et al., 2012). It has also been suggested that hyperandrogenism may play an important role in the development of T2DM in women with PCOS (Zhao et al., 2010), although not all studies agree (Mani et al., 2013).

Reasons for discrepancy between the results might be the cross-sectional design of studies (Ehrmann et al., 1999; Stepto et al., 2013; Joham et al., 2014) and the use of self-reported diagnosis of T2DM in the prospective ones (Elting et al., 2001; Boudreaux et al., 2006). In addition, the definitions for IFG, IGT, T2DM and PCOS have also varied and most of the studies using an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) have been performed in a population arising from clinical practices (Norman et al., 2001; Hudecova et al., 2011; Celik et al., 2014). Lastly, only a few studies have matched the results for BMI (Hudecova et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2011).

Despite the aforementioned inconsistent results, consensus statements by the Endocrine Society (Legro et al., 2013), the Androgen Excess and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Society (AE-PCOS) (Wild et al., 2010) and the Australian PCOS Alliance guidelines (Evidence-based guidelines for the assessment and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. 2015), all recommend that women with PCOS, especially those with gestational diabetes or family history of T2DM, should be screened for T2DM. The AE-PCOS Society recommends the OGTT in women with PCOS and BMI over 30 kg/m2 or alternatively in normal weight women with PCOS and advanced age (>40 years) (Wild et al., 2010). The consensus of European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) and the American Society of Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) recommends that screening should be performed in women with PCOS in the following conditions: hyperandrogenism with anovulation, acanthosis nigricans or obesity (BMI > 30 kg/m2) (Fauser et al., 2012). The Australian PCOS Alliance recommends OGTT to be performed every second year in all women with PCOS and annually in those with additional risk factors for T2DM (Evidence-based guidelines for the assessment and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. 2015 ). The latest recommendation, provided by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologist (AACE), American College of Endocrinologist and AE-PCOS Society, suggested performance of OGTT every 1–2 years based on BMI and yearly in women with IGT (Goodman et al., 2015). However, we lack appropriate longitudinal studies to provide clear supportive evidence for these statements.

The main aim of the present study was to determine the population-based risk for prediabetes and T2DM by the age of 46 years among women with PCOS compared with non-PCOS control women. Secondly, we took advantage of the long follow-up time of the study population to clarify the respective roles of overweight/obesity and more specifically long-term weight gain from adolescence until late adulthood for the development of prediabetes or T2DM in women with PCOS.

Materials and Methods

Study population

This study is based on the Northern Finland Birth Cohort 1966 Study (NFBC1966), which is a large prospective general population-based epidemiological and longitudinal birth cohort that aims to promote health and well-being of the population. The inclusion criteria to this birth cohort were to have expected term during year 1966 in the two Northernmost provinces in Finland (Oulu and Lapland) and thus this birth cohort comprises all individuals born alive in that area during that year (12,231 births, 5889 females, 96.3% of all births during 1966 in that area). Enrolment in this database was started at the 24th gestational week and, so far data from this cohort have been collected from birth, and at 1, 14, 31 and 46 years. Postal questionnaires were sent at ages of 14, 31 and 46 years to all of the individuals belonging to this cohort, and the present study utilized all these data collection points. At ages 31 and 46 years they were also invited to clinical examinations (http://www.oulu.fi/nfbc/node/40683, last accessed 16 December 2016).

In adolescence (14 years) a postal questionnaire, including questions about weight and height, was sent to 5764 females and 5455 of them answered (response rate 95%), with help from their parents. Clinical data were not collected at that age.

At age 31 years, study subjects responded to a comprehensive postal questionnaire (n = 4523 females, response rate 80%) including anthropometric questions and two questions on excessive body hair and oligoamenorrhoea: Is your menstrual cycle often (more than twice a year) longer than 35 days?; Do you have bothersome, excessive body hair growth? Of the women who responded to the questionnaire, 4.2% (n = 125) reported both oligoamenorrhoea and hirsutism (OA+H), after excluding pregnant women and those using hormonal preparations (n = 1459) or denying data usage (n = 41). The validity of this questionnaire to distinguish PCOS cases has already been shown in our previous studies from the same cohort as the women with both OA+H present the typical metabolic and hormonal features of PCOS (Taponen et al., 2003, 2004). Furthermore, 3127 (76%) women also participated in the clinical examination including anthropometric measurements and blood samples.

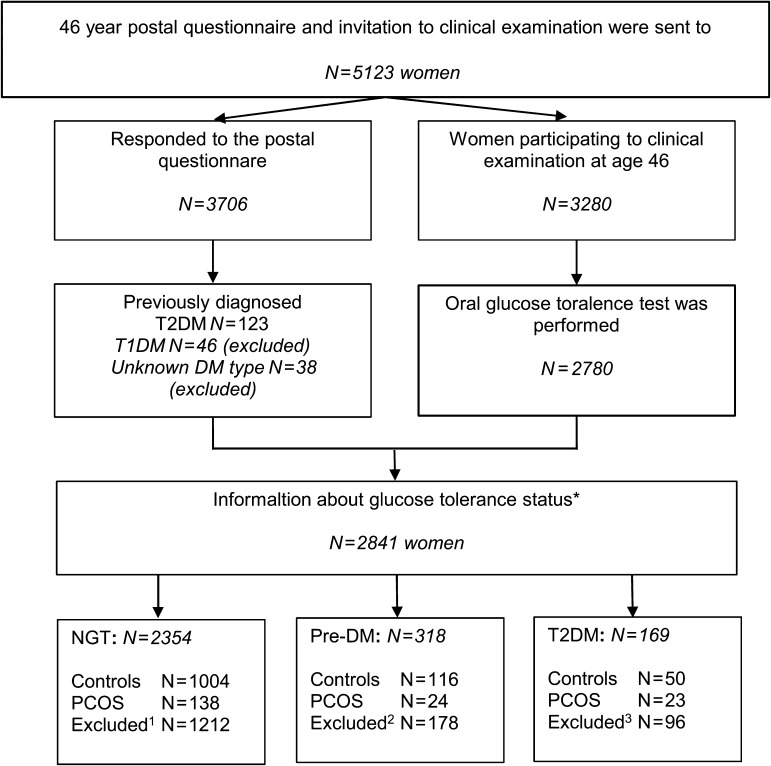

At age 46 years, a postal questionnaire was sent to 5123 women and 3706 (72%) of them responded (Fig. 1). The questionnaire included a question ‘Have you ever been diagnosed as having polycystic ovaries and/or polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) during your life?’ to which 181 responded ‘yes’. Women reporting both OA+H at age 31 years and/or diagnosis of PCOS by 46 years were considered as PCOS cases (n = 279). The women without any PCOS symptoms at 31 years and without diagnosis of PCOS by 46 years were considered as non-PCOS controls (n = 1577).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the prospective, population-based cohort study of the risk of Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) in women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).

NGT: Normal glucose tolerance, Pre-DM: Prediabetes.

*Some of the women with previously diagnosed T2DM had participated in the oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), as they were not currently using medication and did not have fasting capillary blood glucose level over 8.0 mmol/l.

1Excluded from NGT group: women using hormonal contraception or pregnant at age 31 years (n = 734), with isolated oligoamenorrhoea at age 31 years (n = 127), with isolated hirsutism at age 31 years (n = 139) and women who did not respond to the question about PCOS symptoms at age 31 years or about diagnosis of PCOS at 46 years (n = 212).

2Excluded from Pre-DM group: women using hormonal contraception or pregnant at age 31 years (n = 95), with isolated oligoamenorrhoea at age 31 years (n = 22), with isolated hirsutism at age 31 years (n = 16) and women who did not respond to the question about PCOS symptoms at age 31 years or about diagnosis of PCOS at 46 years (n = 45).

3Excluded from T2DM group: women using hormonal contraception or pregnant at age 31 years (n = 44), with isolated oligoamenorrhoea at age 31 years (n = 12), with isolated hirsutism at age 31 years (n = 13) and women who did not respond to the question about PCOS symptoms at age 31 years or about diagnosis of PCOS at 46 years (n = 27).

At age 46 years, 3280 women (64% of 5123 women invited) participated in the clinical examination including anthropometric measurements and blood sampling. A flow chart of the NFBC66 study is presented in Supplementary Figure 1. Furthermore, a 2-h OGTT was performed in 2780 women after overnight (12 h) fasting. Both serum insulin and plasma glucose levels were measured at baseline and at 30, 60 and 120 min after 75 g glucose. The glucose levels were analysed according to the World Health Organization standards (Alberti and Zimmet, 1998): Normal glucose tolerance (NGT), IFG, IGT, Pre-DM: IFG or IGT. Furthermore, the level of glucose metabolism was classified more accurately as previously diagnosed T2DM (pT2DM), new T2DM diagnosis revealed by OGTT at age 46 years (nT2DM: fP-glucose ≥7.0 mmol/l and/or 2- h glucose in OGTT ≥ 11.1 mmol/l), all Type 2 diabetes mellitus diagnosis (T2DM: pT2DM or nT2DM), abnormal glucose metabolism (AGM: Pre-DM or T2DM) and new AGM disturbance in OGTT at age 46 years (nAGM: IFG, IGT or nT2DM). All the pT2DM reported in postal questionnaires were verified and completed from hospital discharge and national drug registers from the Social Insurance Institution of Finland.

Laboratory methods

At age 31 years, sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) was assayed as previously described (Taponen et al., 2003), and at 46 years by chemiluminometric immunoassay (Immulite 2000, Siemens Healthcare, Llanberis, UK). The serum samples for testosterone at age 31 and 46 years were assayed using Agilent triple quadrupole 6410 liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry equipment (Agilent Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA). The normal upper limit for testosterone was 2.3 nmol/l at age 31 years and 1.70 nmol/l at 46 years, based on 97.5% percentile calculated in this study population. More detailed information about laboratory methods are available in Supplementary Data.

Statistical methods

Differences in continuous parameters were analysed by Student's t-test and Mann–Whitney U-test when appropriate. Continuous data were presented as means ± SD or median with 25% and 75% quartiles. Categorical data were analysed using cross-tabulation and Pearson's Chi-squared (χ2) test. Binary logistic regression models were employed to investigate the factors associated with pre-DM, T2DM, nAGM and AGM and the results were reported as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% Cls. Results were adjusted for consumption of alcohol (g/day), smoking, education, current use of cholesterol-lowering drugs and of combined contraceptive pills at age 46 years. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 22.0 (SPSS, Inc., 1989, 2013, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical approval

The study followed the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The Ethics Committee of the Northern Ostrobothnia Hospital District has approved the research. All participants took part on a voluntary basis and signed an informed consent.

Results

Prevalence of prediabetes, T2DM, AGM and nAGM in women with PCOS

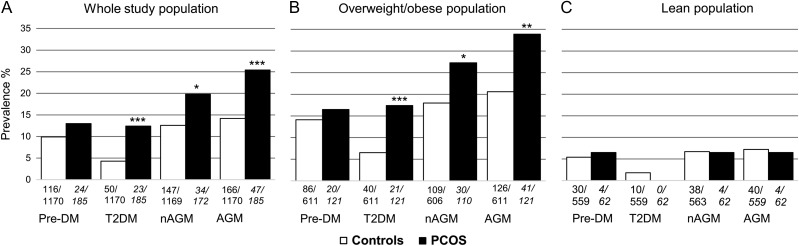

At baseline, women with PCOS were more obese, hyperglycaemic, insulin resistant and hyperandrogaenic than controls at age 46 years, but these differences disappeared after adjusting for BMI except for testosterone, free androgen index (FAI) and glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) (Table I). Women with PCOS had significantly greater prevalence of T2DM, and especially AGM and nAGM, compared with control women in the whole population (Fig. 2A), and also when comparing overweight/obese (BMI ≥ 25.0 kg/m2) women with PCOS to overweight/obese control women (Fig. 2B). The vast majority of the normal weight women with PCOS had NGT (93.6%, n = 58) as only four (6.5%) of them exhibited prediabetes, and none of them T2DM (Fig. 2C).

Table I.

Baseline profile of controls and women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) at age 46 years.

| Parameter | Controls (n= 1141–1569) | PCOS women (n= 153–265) | P-value | BMI-adj. P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.34 ± 5.3 | 28.60 ± 6.3 | <0.001 | |

| Waist (cm) | 84.00 [77.00; 94.00] | 88.50 [81.00; 99.05] | <0.001 | |

| Testosterone (nmol/l) | 0.83 [0.63; 1.05] | 0.89 [0.68; 1.11] | 0.017 | 0.009 |

| SHBG (nmol/l) | 53.30 [37.68; 73.65] | 49.15 [34.10; 66.00] | 0.003 | 0.450 |

| FAI | 1.53 [1.07; 2.17] | 1.82 [1.38; 2.60] | <0.001 | 0.006 |

| fP-glucose (mmol/l) | 5.34 ± 0.6 | 5.50 ± 0.8 | 0.006 | 0.070 |

| AUC-glucose | 13.09 ± 2.9 | 13.61 ± 3.1 | 0.032 | 0.359 |

| HbA1c (mmol/mol) | 35.78 ± 4.6 | 37.09 ± 6.8 | 0.008 | 0.029 |

| fS-Insulin (mU/I) | 7.10 [4.9; 10.8] | 8.60 [6.0; 12.5] | 0.001 | 0.337 |

| AUC-Insulin | 94.90 [69.5; 148.9] | 114.8 [79.2; 171.9] | 0.002 | 0.505 |

| HOMA–IR | 1.67 [1.15; 2.59] | 2.06 [1.37; 3.11] | <0.001 | 0.185 |

| Matsuda-index | 5.22 [3.35; 7.46] | 4.38 [2.90; 6.55] | 0.002 | 0.359 |

SHBG, sex hormone-binding globulin; FAI, free androgen index; fP, fasting-plasma; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin A1c; HOMA–IR, homoeostasis model assessment–insulin resistance. The number of women in each analysis varies due to some missing data. The results are reported as mean ± SD or median with [25% lower quartile; 75% upper quartile]. The differences between control and PCOS groups were analysed by Student's t-test or Mann–Whitney U-test when appropriate. The results were adjusted for BMI at age 46 years using univariate general linear modelling (ANCOVA). The women using combined contraceptive pills at age 46 years were excluded from the analysis of serum levels of testosterone, SHBG and FAI.

Figure 2.

The prevalence of pre-DM, T2DM, nAGM and AGM in whole study population (A), in overweight/obese population (B) and in lean population (C).

AGM: Abnormal glucose tolerance (including pre-DM, newly detected T2DM [nT2DM] and previously diagnosed T2DM [pT2DM]). Newly detected AGM (nAGM): Pre-DM or nT2DM in the OGTT at age 46 years. The BMI-status is based on 46-years data.

*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 when comparing women with PCOS to control women. The prevalences and differences between the PCOS and control women were analysed by cross-tabulation and Chi-squared test. Below each bar, the numerator describes the number of affected women and the denominator describes the total number of women in each group.

Most of the T2DM cases in women with PCOS had already been diagnosed by age 46 years (n = 19, 82.6%), whereas only four new T2DM cases among women with PCOS were revealed by the OGTT at 46 years, the mean BMI of these women being 36.0 ± 5.3 kg/m2.

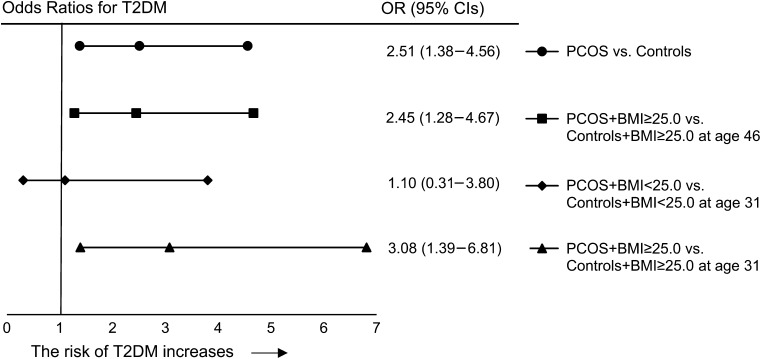

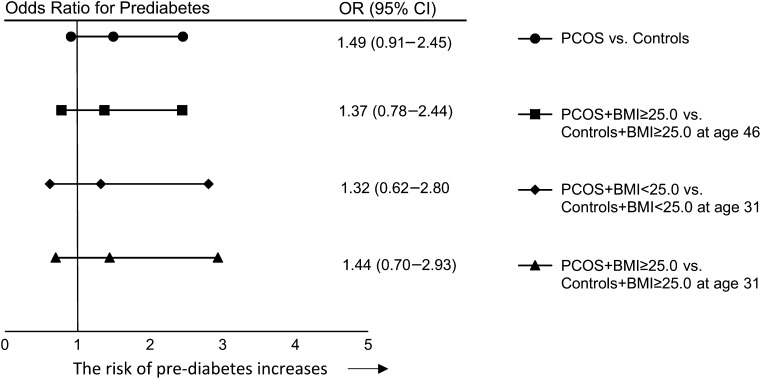

Binary logistic regression analysis

PCOS per se significantly increased the risk of T2DM by 2-fold (Fig. 3) as well as AGM (OR = 1.8 [1.2–2.7]) and nAGM (OR = 1.7 [1.1–2.6]). The risk of T2DM (OR = 2.45 [1.28–4.67]) and AGM (OR = 1.8 [1.1–2.8]), but not nAGM, remained significantly increased when comparing overweight/obese women with PCOS to overweight/obese control women (Fig. 3). PCOS per se did not significantly increase risk of prediabetes (Fig. 4). Normal weight women with PCOS did not have increased risks for any abnormalities of glucose metabolism.

Figure 3.

Odds ratios (ORs) for Type 2 diabetes. The analysis has been made by binary logistic regression analysis and the ORs are adjusted for education level, alcohol consumption, smoking, and current use of combined contraceptives and of cholesterol-lowering drugs. Age is given in years.

Figure 4.

ORs for prediabetes. The analysis has been made by binary logistic regression analysis and the ORs are adjusted for education level, alcohol consumption, smoking, and current use of combined contraceptives and of cholesterol-lowering drugs. Age is given in years.

The presence of both PCOS and BMI ≥ 25.0 kg/m2 at age 46 years dramatically increased the risk of prediabetes (OR = 4.4 [2.3–8.5]), T2DM (OR = 12.4 [5.1–30.1]), AGM (OR = 6.2 [3.7–10.6]) and nAGM (OR = 5.4 [3.1–9.5]), when compared with normal weight controls. The regression analysis, including PCOS and BMI at age 46 years as separate parameters, showed that both remained independently associated with T2DM (PCOS: OR = 2.2 [1.2–4.0] and BMI: OR = 1.18 [1.1–1.2]). However, we were unable to statistically assess the interaction between PCOS and BMI due to the lack of normal weight women who had both PCOS and T2DM.

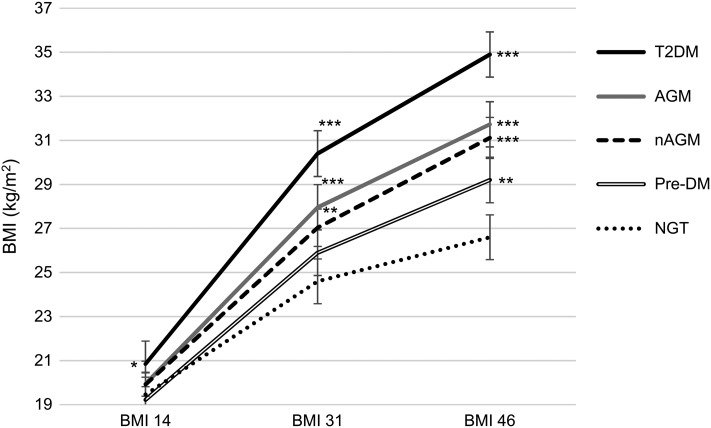

Differences between women with PCOS and abnormal versus NGT

Women with PCOS and AGM had greater BMI and waist circumference at ages 31 and 46 years as well as greater weight gain through life, especially between ages 14 and 31 years, compared with PCOS women with NGT (Fig. 5 and Table II). Especially, the increase in weight between 14 and 31 years was significantly greater in women with PCOS and T2DM compared to PCOS women with NGT (median with [25%; 75% quartiles]: 27.25 kg [20.43; 34.78] versus 13.80 kg [8.55; 20.20], P < 0.001). However, women with PCOS and AGM had similar levels of testosterone at age 31 and 46 years when compared with women with PCOS and NGT (Table II). .

Figure 5.

Development of BMI during life in the women with PCOS according to the glucose metabolism status assessed at age 46 years. BMI values are reported as mean ± SE at each time point (14, 31 and 46 years) and the differences between groups were analysed using Mann–Whitney U-test and compared with the women with NGT in the same time point.

*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001

AGM: Pre-DM or T2DM [i.e. previously diagnosed or OGTT screened T2DM], nAGM: Pre-DM or screened T2DM in the OGTT. T2DM: including both previously diagnosed or OGTT detected.

At age 14 years BMI information was available from 115 women in the PCOS + NGT group, 18 women in the PCOS + T2DM group, 21 women in the PCOS + pre-DM group, 39 women in the PCOS + AGM group and 29 women in the PCOS + nAGM group. At 31 years, BMI information was available from 134 women in the PCOS + NGT group, 22 women in the PCOS + T2DM group, 23 women in the PCOS + pre-DM group, 45 women in the PCOS + AGM group and 33 women in the PCOS + nAGM group. At 46 years, BMI information was available from 138 women in the PCOS + NGT group, 21 women in the PCOS + T2DM group, 24 women in the PCOS + pre-DM group, 45 women in the PCOS + AGM group and 34 women in the PCOS + nAGM group.

Table II.

Clinical characteristics of the women with PCOS according to glucose metabolism.

| Women with PCOS by age 46 years | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NGT (n = 91–138) | T2DM (n = 10–22) | Pre-DM (n = 17–24) | AGM (n = 29–45) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) 14 years | 19.22 [18.02; 20.58] | 20.00 [19.10; 23.22]a | 18.70 [17.44; 22.16] | 19.47 [18.24; 22.35] |

| BMI (kg/m2) 31 years | 23.46 [21.47; 26.34] | 31.66 [26.54; 35.13]c | 25.66 [22.94; 29.20] | 26.66 [24.23; 32.96]c |

| BMI (kg/m2) 46 years | 25.70 [23.50; 29.52] | 34.55 [31.90; 37.71]c | 29.47 [26.66; 33.18]b | 31.91 [28.69; 36.80]c |

| Change of weight 14–31 years | 13.80 [8.55; 20.20] | 27.25 [20.43; 34.78]c | 18.35 [11.48; 26.40]a | 22.45 [15.55; 32.53]c |

| Change of weight 31–46 years | 5.30 [1.28; 11.10] | 12.20 [−1.0; 19.98]a | 9.70 [4.90; 13.60]a | 10.80 [3.30; 15.50]b |

| Change of weight 14–46 years | 19.40 [13.45; 27.85] | 41.35 [25.53; 53.58]c | 27.90 [20.40; 37.10]b | 34.30 [22.20; 43.40]c |

| Waist 31 years | 79.00 [72.0; 88.0] | 95.00 [84.0; 105.0]b | 85.50 [76.25; 92.60] | 86.75 [79.38; 98.13]b |

| Waist 46 years | 86.00 [79.5; 92.6] | 106.50 [99.8; 114.1]c | 94.00 [86.0; 101.0]b | 99.00 [92.0; 107.8]c |

| Change of waist 31–46 years | 6.85 [1.4; 13.0] | 19.25 [7.1; 30.3]a | 9.90 [1.6; 17.3] | 11.50 [4.0; 22.8]a |

| Testosterone (nmol/l) 31 years | 2.20 [1.70; 2.98] | 2.15 [1.68; 3.05] | 2.20 [1.80; 2.50] | 2.20 [1.80; 2.60] |

| Testosterone (nmol/l) 46 years | 0.90 [0.69; 1.08] | 0.78 [0.53; 0.94] | 0.89 [0.61; 1.12] | 0.81 [0.57; 1.08] |

| SHBG (nmol/l) 31 years | 54.40 [37.05; 75.80] | 28.20 [18.05; 43.83]c | 39.30 [23.80; 47.10]b | 32.20 [21.45; 46.45]c |

| SHBG (nmol/l) 46 years | 54.00 [40.10; 70.90] | 31.70 [25.00; 45.30]b | 30.50 [24.10; 42.70]c | 30.60 [24.40; 42.80]c |

| HbA1c (mmol/mol) | 35.44 ± 3.98 | 43.00 ± 6.01c | 37.83 ± 4.05b | 39.74 ± 5.41c |

Data are expressed as mean ± SD or median with [25%; 75% quartiles]. The differences between control and PCOS groups were analysed by Student's t-test or Mann–Whitney U-test when appropriate. The numbers of women in separate analyses varies due to non-response to some items. aP-value < 0.05, bP-value < 0.01, cP-value < 0.001 compared to women with NGT. NGT, normal glucose tolerance; T2DM, Type 2 diabetes; pre-DM, prediabetes; AGM, abnormal glucose tolerance. Weight is reported in kilograms and waist in centimeters. The women using combined contraceptive pills at current age have been excluded from the testosterone and SHBG analysis.

Discussion

The present study provides a unique prospective population-based follow-up study to address the development of glucose metabolism disturbances in women with PCOS. The main finding was that the risk of T2DM in women with PCOS is mainly attributable to overweight/obesity and that normal weight women with PCOS are not at increased risk for prediabetes or T2DM. Long-term weight gain, most especially in early adulthood between ages 14 and 31 years, was significantly greater in women with PCOS diagnosed with T2DM by age 46 years. Although this study is not an intervention study to investigate the effect of weight reduction on the risk of T2DM in women with PCOS, our results support the importance of maintaining a normal weight during early adulthood especially in women with PCOS to avoid the onset of T2DM.

The strengths of this study are the prospective population-based cohort study design and the longest follow-up time compared with the longitudinal studies investigating the effect of BMI on glucose metabolism in women with PCOS. The present study is characterized by high participation and response rates and low dropout rates. Furthermore, anthropometric parameters were mostly clinically measured. Limitations of this study include self-reported symptoms and diagnosis of PCOS. Hirsutism is subjective and may be easily over-reported. However, we have previously shown that self-reported isolated hirsutism does correlate with increased androgen secretion in this population and that self-reported oligoamenorrhoea and hirsutism can identify women with the typical endocrine and metabolic profiles of PCOS (Taponen et al., 2003, 2004). The questionnaire at age 46 years did not distinguish between those women who were found to have polycystic ovaries on ultrasound (PCO) and those with established PCOS. However, women with PCO who might be symptom-free would exhibit milder hormonal and metabolic disorders than symptomatic women and thus the differences between the groups would have been even greater if we had excluded women with PCO only.

In most of the previous studies, the prevalence of T2DM in women with PCOS has been around 10% (Ehrmann et al., 1999; Hudecova et al., 2011; Joham et al., 2014), although the results have been varying (Elting et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2011) reflecting the differences in study populations and definitions of T2DM. In line with some of the earliest data on T2DM in women with PCOS, our study population exhibited a prevalence of 12.4% for T2DM in women with PCOS at age 46 years, the prevalence being over 2-fold compared with control women and also compared with the general Finnish female population of similar age (5.2%) (Ilanne-Parikka et al., 2004).

Women with PCOS often present with overweight and obesity, and despite intensive research previous studies addressing the causal relationship between BMI and PCOS have been inconclusive. Our previous study reported that weight gain, especially in early adulthood, associated with later diagnosis of PCOS (Ollila et al., 2016). In addition, previous studies have also been inconsistent about whether PCOS per se presents as an independent risk factor for developing T2DM (Legro et al., 1999), whether there is a synergistic effect between PCOS and BMI (Boudreaux et al., 2006; Joham et al., 2014) or whether the association between PCOS and T2DM is entirely attributable to obesity (Gambineri et al., 2012). In the present study, the risk of T2DM in women with PCOS was mainly attributable to overweight and obesity, but the presence of both an increased BMI and PCOS further increased the risk of T2DM. The women with PCOS and T2DM had significantly greater BMI at all three time points (14, 31 and 46 years) and greater lifelong weight gain than women with PCOS and NGT, in line with previous studies (Norman et al., 2001; Celik et al., 2014). Our findings were also in agreement with another follow-up study, showing that the PCOS subjects converting from normal to AGM exhibited greater BMI, abdominal obesity and weight gain compared to those remaining normoglycaemic (Norman et al., 2001), and also with a study showing that a 1% increase in BMI is associated with a 2% increase in risk for T2DM (Morgan et al., 2012). The novel and clinically important finding of the present study is that the greatest weight gain in the women with PCOS developing AGM occurred already in early adulthood, and thus may identify a sensitive time-window when preventive action, such as exercise and dietary counselling, against T2DM development in women with PCOS should be implemented.

Some studies have reported that normal weight women with PCOS are at risk for T2DM (Legro et al., 1999; Wang et al., 2011). Our results suggest that, at least in this unselected general population, normal weight women with PCOS do not have increased risk of prediabetes or T2DM. To support this view, other studies in patient populations with an established diagnosis of PCOS have also reported that only obese women with PCOS are at increased risk of T2DM (Boudreaux et al., 2006; Espinos-Gomez et al., 2009; Gambineri et al., 2012). Normal weight women with PCOS have been reported to be insulin resistant (Stepto et al., 2013), but it has also been reported that insulin resistance ameliorates during aging in non-obese women with PCOS, possibly due to decreasing androgen levels (Livadas et al., 2014). We do, however, acknowledge that the numbers of subjects with disturbances of glucose homoeostasis in this subgroup of PCOS women was relatively small. In our study population, hyperandrogenaemia did not seem to be an additional risk for AGM, in line with a previous retrospective cohort study (Mani et al., 2013).

All our results strongly support the recommendation for OGTT screening in overweight/obese women with PCOS as suggested by ESHRE/ASRM consensus (Fauser et al., 2012) and AE-PCOS Society (Wild et al., 2010). However, our data do not support the AE-PCOS recommendation of performing OGTT in normal weight PCOS women older than 40 years, as they did not have increased risk of either prediabetes or T2DM at age 46 years.

In conclusion, the risk of AGM in women with PCOS is mainly due to overweight/obesity, although these two factors have a synergistic effect on the development of T2DM. Moreover, weight gain especially during early adulthood seemed to be a crucial risk factor for the development of AGM. Normal weight women with PCOS in this population were not at increased risk for prediabetes or T2DM. These results emphasize the role of weight management during adolescence and early adulthood to prevent the development of prediabetes and T2DM in women with PCOS, although this was not an intervention study. Furthermore, our results suggest that regular screening for glucose metabolism disturbances should be targeted to the overweight and obese women with PCOS and thus encourage optimal use of the limited resources of medical care systems.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the late Professor Paula Rantakallio (Launcher of NFBCs), the participants in the 31 and 46 years study and the NFBC project center.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at Human Reproduction online.

Authors’ roles

L.C.-M.P., T.T.P., J.S.T., J.A., M.-R.J., S.K.-K., M.-M.E.O. and S.W. conceived and designed the study. M.-M.E.O. and S.W. carried out the literature search. K.P. and A.R. performed the laboratory analysis. M.-M.E.O., S.W. and J.J. analysed the data and all authors contributed to its interpretation. All authors participated in the manuscript drafting and revision process and have approved this submission for publication.

Funding

Finnish Medical Foundation; North Ostrobothnia Regional Fund; Academy of Finland (project grants 104781, 120315, 129269, 1114194, 24300796, Center of Excellence in Complex Disease Genetics and SALVE); Sigrid Juselius Foundation; Biocenter Oulu; University Hospital Oulu and University of Oulu (75617); Medical Research Center Oulu; National Institute for Health Research (UK); National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant (5R01HL087679-02) through the STAMPEED program (1RL1MH083268-01); National Institute of Health/National Institute of Mental Health (5R01MH63706:02); ENGAGE project and grant agreement HEALTH-F4-2007–201413; EU FP7 EurHEALTH Ageing-277849 European Commission and Medical Research Council; UK (G0500539, G0600705, G1002319, PrevMetSyn/SALVE) and Medical Research Center; Centenary Early Career Award.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

- Alberti KG, Zimmet PZ. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabet Med 1998;15:539–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous Evidence-based Guidelines for the Assessment and Management of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Jean Hailes for Women's Health on behalf of the PCOS Australian Alliance. 2015. Melbourne: Available online at https://jeanhailes.org.au/health-professionals/tools (16 December 2016, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- Baptiste CG, Battista MC, Trottier A, Baillargeon JP. Insulin and hyperandrogenism in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2010;122:42–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudreaux MY, Talbott EO, Kip KE, Brooks MM, Witchel SF. Risk of T2DM and impaired fasting glucose among PCOS subjects: results of an 8-year follow-up. Curr Diab Rep 2006;6:77–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celik C, Tasdemir N, Abali R, Bastu E, Yilmaz M. Progression to impaired glucose tolerance or type 2 diabetes mellitus in polycystic ovary syndrome: a controlled follow-up study. Fertil Steril 2014;101:1123–1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Papavassiliou AG. Molecular mechanisms of insulin resistance in polycystic ovary syndrome. Trends Mol Med 2006;12:324–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrmann DA, Barnes RB, Rosenfield RL, Cavaghan MK, Imperial J. Prevalence of impaired glucose tolerance and diabetes in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Diabetes Care 1999;22:141–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elting MW, Korsen TJ, Bezemer PD, Schoemaker J. Prevalence of diabetes mellitus, hypertension and cardiac complaints in a follow-up study of a Dutch PCOS population. Hum Reprod 2001;16:556–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinos-Gomez JJ, Corcoy R, Calaf J. Prevalence and predictors of abnormal glucose metabolism in Mediterranean women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Gynecol Endocrinol 2009;25:199–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fauser BC, Tarlatzis BC, Rebar RW, Legro RS, Balen AH, Lobo R, Carmina E, Chang J, Yildiz BO, Laven JS et al. Consensus on women's health aspects of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): the Amsterdam ESHRE/ASRM-sponsored 3rd PCOS consensus workshop group. Fertil Steril 2012;97:28–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franks S. Polycystic ovary syndrome. N Engl J Med 1995;333:853–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gambineri A, Patton L, Altieri P, Pagotto U, Pizzi C, Manzoli L, Pasquali R. Polycystic ovary syndrome is a risk factor for type 2 diabetes: results from a long-term prospective study. Diabetes 2012;61:2369–2374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman NF, Cobin RH, Futterweit W, Glueck JS, Legro RS, Carmina E. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, American College of Endocrinology, and Androgen Excess and PCOS Society Disease State Clinical Review: Guide to the Best Practices in the Evaluation and Treatment of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome - Part 2. Endocr Pract 2015;21:1415–1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudecova M, Holte J, Olovsson M, Larsson A, Berne C, Poromaa IS. Diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome--a long term follow-up. Hum Reprod 2011;26:1462–1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilanne-Parikka P, Eriksson JG, Lindstrom J, Hamalainen H, Keinanen-Kiukaanniemi S, Laakso M, Louheranta A, Mannelin M, Rastas M, Salminen V et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome and its components: findings from a Finnish general population sample and the Diabetes Prevention Study cohort. Diabetes Care 2004;27:2135–2140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joham AE, Ranasinha S, Zoungas S, Moran L, Teede HJ. Gestational diabetes and type 2 diabetes in reproductive-aged women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2014;99:447–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legro RS, Arslanian SA, Ehrmann DA, Hoeger KM, Murad MH, Pasquali R, Welt CK, Endocrine Society . Diagnosis and treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013;98:4565–4592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legro RS, Kunselman AR, Dodson WC, Dunaif A. Prevalence and predictors of risk for type 2 diabetes mellitus and impaired glucose tolerance in polycystic ovary syndrome: a prospective, controlled study in 254 affected women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1999;84:165–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livadas S, Kollias A, Panidis D, Diamanti-Kandarakis E. Diverse impacts of aging on insulin resistance in lean and obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome: evidence from 1345 women with the syndrome. Eur J Endocrinol 2014;171:301–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mani H, Levy MJ, Davies MJ, Morris DH, Gray LJ, Bankart J, Blackledge H, Khunti K, Howlett TA. Diabetes and cardiovascular events in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a 20-year retrospective cohort study. Clin endocrinol (Oxf) 2013;78:926–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran LJ, Misso ML, Wild RA, Norman RJ. Impaired glucose tolerance, type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update 2010;16:347–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan CL, Jenkins-Jones S, Currie CJ, Rees DA. Evaluation of adverse outcome in young women with polycystic ovary syndrome versus matched, reference controls: a retrospective, observational study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012;97:3251–3260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman RJ, Masters L, Milner CR, Wang JX, Davies MJ. Relative risk of conversion from normoglycaemia to impaired glucose tolerance or non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus in polycystic ovarian syndrome. Hum Reprod 2001;16:1995–1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ollila MM, Piltonen T, Puukka K, Ruokonen A, Järvelin MR, Tapanainen JS, Franks S, Morin-Papunen L. Weight gain and dyslipidemia in early adulthood associate with polycystic ovary syndrome: prospective cohort study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2016;101:739–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepto NK, Cassar S, Joham AE, Hutchison SK, Harrison CL, Goldstein RF, Teede HJ. Women with polycystic ovary syndrome have intrinsic insulin resistance on euglycaemic-hyperinsulaemic clamp. Hum Reprod 2013;28:777–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taponen S, Ahonkallio S, Martikainen H, Koivunen R, Ruokonen A, Sovio U, Hartikainen AL, Pouta A, Laitinen J, King V et al. Prevalence of polycystic ovaries in women with self-reported symptoms of oligomenorrhoea and/or hirsutism: Northern Finland Birth Cohort 1966 Study. Hum Reprod 2004;19:1083–1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taponen S, Martikainen H, Jarvelin MR, Laitinen J, Pouta A, Hartikainen AL, Sovio U, McCarthy MI, Franks S, Ruokonen A. Hormonal profile of women with self-reported symptoms of oligomenorrhea and/or hirsutism: Northern Finland Birth Cohort 1966 study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003;88:141–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ET, Calderon-Margalit R, Cedars MI, Daviglus ML, Merkin SS, Schreiner PJ, Sternfeld B, Wellons M, Schwartz SM, Lewis CE et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome and risk for long-term diabetes and dyslipidemia. Obstet Gynecol 2011;117:6–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wild RA, Carmina E, Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Dokras A, Escobar-Morreale HF, Futterweit W, Lobo R, Norman RJ, Talbott E, Dumesic DA. Assessment of cardiovascular risk and prevention of cardiovascular disease in women with the polycystic ovary syndrome: a consensus statement by the Androgen Excess and polycystic ovary syndrome (AE-PCOS) Society. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010;95:2038–2049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Zhong J, Mo Y, Chen X, Chen Y, Yang D. Association of biochemical hyperandrogenism with type 2 diabetes and obesity in Chinese women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2010;108:48–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.