Abstract

Natural rewards and drugs of abuse can alter dopamine signaling, and ventral tegmental area (VTA) dopaminergic neurons are known to fire action potentials tonically or phasically under different behavioral conditions. However, without technology to control specific neurons with appropriate temporal precision in freely behaving mammals, the causal role of these action potential patterns in driving behavioral changes has been unclear. We used optogenetic tools to selectively stimulate VTA dopaminergic neuron action potential firing in freely behaving mammals. We found that phasic activation of these neurons was sufficient to drive behavioral conditioning and elicited dopamine transients with magnitudes not achieved by longer, lower-frequency spiking. These results demonstrate that phasic dopaminergic activity is sufficient to mediate mammalian behavioral conditioning.

Dopaminergic (DA) neurons have been suggested to be involved in the cognitive and hedonic underpinnings of motivated behaviors (1–4). Changes in the firing pattern of DA neurons between low-frequency tonic activity and phasic bursts of action potentials could encode reward prediction errors and incentive salience (5). Consistent with the reward prediction-error hypothesis, DA neuron firing activity is depressed by aversive stimuli (6). However, it remains unclear whether DA neuron activation alone is sufficient to elicit reward-related behaviors. Lesion, electrical stimulation, and psychopharmacology studies have been important but have not allowed causal and temporally precise control of DA neurons in freely moving mammals; for example, electrical stimulation inevitably activates multiple classes of neurons within heterogeneous brain tissue, and pharmacological stimulation does not allow delivery of defined patterns of DA neuron spikes in vivo.

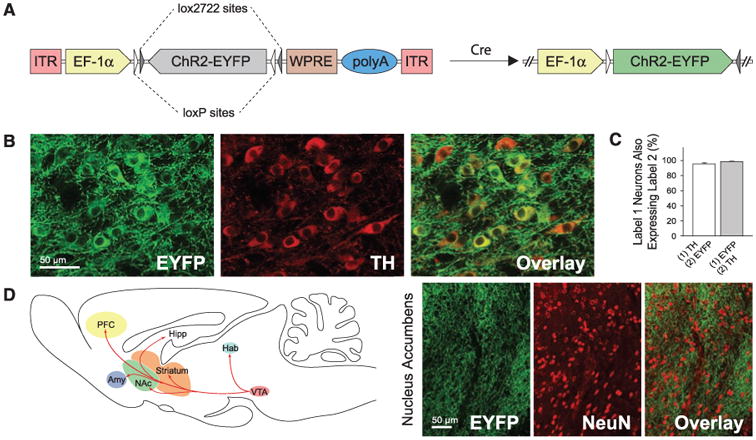

To control DA neurons selectively, we used a Cre-inducible adeno-associated virus (AAV) vector (7, 8) carrying the gene encoding the light-activated cation channel channelrhodopsin-2 (ChR2) in-frame fused to enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (ChR2-EYFP) (9–11). To ensure that there would be no substantial expression leak in nontargeted cell types, we designed the Cre-inducible AAV vector with a double-floxed inverted open reading frame (ORF), wherein the ChR2-EYFP sequence is present in the anti-sense orientation (Fig. 1A). Stereotactic delivery of this vector into the VTA of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH)∷ internal ribosomal entry site (IRES)– Cre transgenic mice enables DA neuron-specific expression of ChR2-EYFP. Upon transduction, Cre-expressing TH cells invert the ChR2-EYFP ORF in irreversible fashion and thereby activate sustained ChR2-EYFP expression under the strong, constitutively active elongation factor 1a (EF-1α) promoter.

Fig. 1.

Specific ChR2 expression in DA neurons. (A) Schematic of the Cre-dependent AAV; the gene of interest is doubly flanked by two sets of incompatible lox sites. Upon delivery into TH∷IRES-Cre transgenics, ChR2-EYFP is inverted to enable transcription from the EF-1α promoter. (B) Confocal images showing cell-specific ChR2-EYFP expression (green) in TH neurons (red). (C) Statistics of expression in TH neurons (n = 491); error bars represent SEM throughout. (D) Labeled VTA DA neurons project to downstream brain regions; confocal images of ChR2-EYFP–positive axons (green) innervating target neurons in NAc (NeuN, red).

We validated the specificity and efficacy of this targeting strategy in vivo. In coronal VTA sections of transduced TH∷IRES-Cre brains, ChR2-EYFP specifically co-localized with endogenous TH (Fig. 1B). Greater than 90% of TH-immunopositive cells were positive for ChR2-EYFP near virus injection sites, and more than 50% were positive overall, demonstrating highly efficacious transduction of the TH cells. Of ChR2-EYFP–expressing cells, 98.3 ± 0.5% were co-labeled by TH staining (Fig. 1C), demonstrating high specificity. Expression was stable and persistent for at least 2 months, and ChR2-EYFP–expressing neurons displayed robust projections; EYFP-positive fibers richly innervated local neurons in downstream nucleus accumbens (NAc) (Fig. 1D) (12).

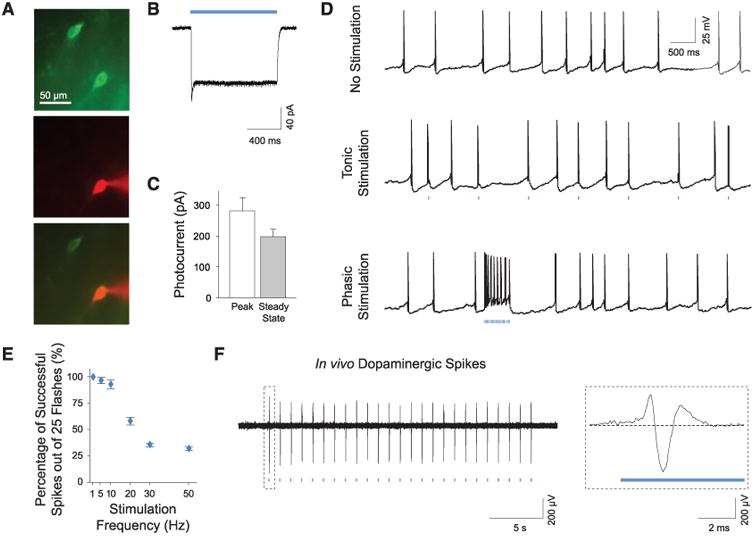

To assess the potential for optogenetic control of transduced cells, we used whole-cell patch clamps to measure light-induced membrane currents in ChR2-expressing DA neurons (Fig. 2A). ChR2-EYFP–expressing cells in the VTA displayed typical electrophysiological properties of DA neurons with a mean resting membrane potential of −56.0 ± 1.8 mV and a mean membrane resistance of 372.3 ± 19.3 megohm (n = 10 cells), consistent with previously reported values for VTA DA neurons (13) and indicating that expression of ChR2 alone does not affect their basic physiology. Under blue light (473 nm) illumination, all patched cells exhibited prominent inward photocurrents (Fig. 2, B and C; n = 10 cells). Trains of light flashes drove action potential firing in ChR2-EYFP neurons; with use of low- and high-frequency light trains, we evoked tonic and phasic DA neuron firing, respectively (Fig. 2D). DA neurons typically do not maintain high-frequency spiking (14); 1- to 5-Hz light pulses drove long DA neuron spike trains reliably, whereas bursting at 20 Hz or greater for prolonged trains evoked action potentials in <50% of light pulses (Fig. 2E and fig. S1; bursts maintaining the >15-Hz spiking characteristic of phasic firing could be elicited simply by using higher-frequency light pulse trains). Optrode recording confirmed that optical stimulation of VTA DA neurons in vivo evoked broad spike waveforms consistent with extracellular waveforms for VTA DA neurons (6) (Fig. 2F and fig. S2).

Fig. 2.

Photoactivation of DA neurons in intact tissue. (A) Recording from transduced neurons in acute VTA slices. Recorded neurons are verified by intracellular dye loading (ChR2-EYFP, green; AlexaFluor 594, red). (B) Continuous blue light (473 nm) evokes inward photocurrents. (C) Summary of photocurrent properties (n = 10). (D) Whole-cell recording of DA neurons showing spontaneous activity and tonic and phasic firing evoked by 1-Hz and 50-Hz light flash trains, respectively (25 flashes, 15 ms per flash). (E) Light-evoked spike trains are reliable over a range of frequencies; percentage of action potentials evoked by 25 light flashes at indicated frequencies (1 to 50 Hz) is shown (n = 7). (F) In vivo optrode recording of VTA DA neurons in a transduced TH∷IRES-Cre anesthetized mouse showing light-evoked DA spikes; see fig. S2 (Inset) Typical triphasic DA extracellular spike.

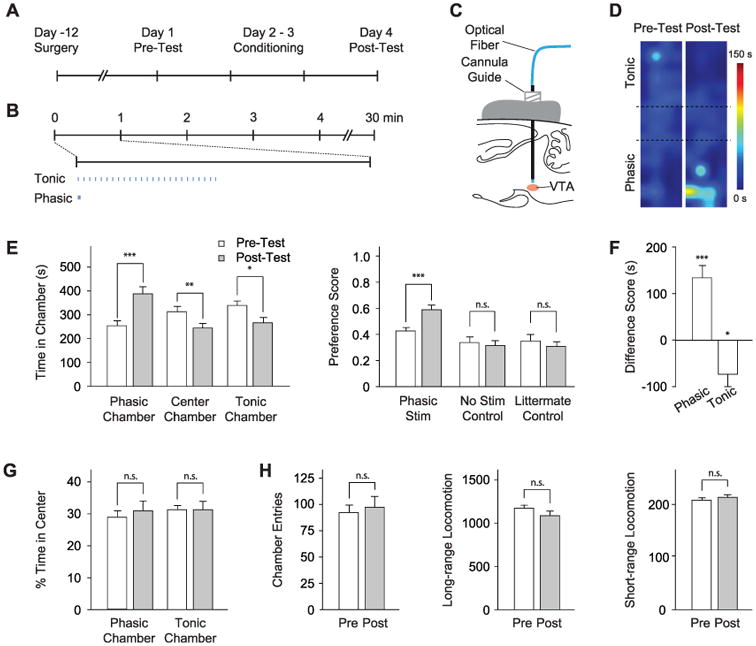

We next tested the behavioral conditioning effects of phasic DA neuron activity via the conditioned place preference (CPP) paradigm (Fig. 3A and fig. S3), with use of phasic opto-genetic stimulation (15) of DA neurons as our conditioning stimuli (Fig. 3, B and C). As a control, we paired the opposite chamber with the same number of light pulses delivered instead at 1 Hz. Mice were subjected to 2 days of conditioning, and conditioned preference was determined by comparing time spent in each chamber of the apparatus. In the first round of experiments, mice received phasic (50-Hz optical stimulation) conditioning in one chamber on the first day of conditioning (day 2), and 1-Hz optical stimulation in the other chamber on the second day of conditioning (day 3); two cohorts of mice were used with the chamber-stimulation pairing reversed to control for spontaneous preference shifts (fig. S3). Mice developed a clear place preference for the chamber associated with phasic optical stimulation by several measures (Fig. 3, D to F; P < 0.001 by Student's t test; n = 13 mice), and both cohorts of mice exhibited this conditioned preference independent of chamber pairing (fig. S5).

Fig. 3.

Photoactivation of DA neurons induces place preference. (A) CPP timeline (see also fig. S3). (B) Light delivery parameters; 25 flashes at 1 or 50 Hz were delivered with a periodicity of 1 min. (C) Optical fiber is inserted through a cannula guide implanted over the VTA to photoactivate DA neurons. (D) Representative density maps showing conditioned preference; pseudocolor represents duration at each position. (E) Conditioning effect of DA neuron modulation. (Left) Comparison of time in each chamber during pretest (white) and posttest (gray). (Right) Comparison of preference scores for experimental (Phasic Stim, n = 13) and control cohorts (No Stim Control, n = 9; Littermate Control, n = 9). n.s. indicates not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001. (F) Difference scores (calculated as the difference between time spent during pre- and posttest in the specified chamber) for each chamber shows a statistically significant shift in place preference. (G) Analysis of anxiety (fractional time in center of a chamber; n = 13). (H) Chamber entries, long-range locomotion (different sequential beam breaks), and short-range locomotion (repeated break of the same beam) during pre- and posttest (n = 13).

We performed two classes of control experiments to validate the results. First, nontransgenic littermates (n = 9) were injected with Cre-dependent ChR2-EYFP AAV and subjected to the same stimulation paradigm as the experimental animals. Separately, TH∷IRES-Cre transgenic mice (n = 9) were injected with Cre-dependent ChR2-EYFP AAV but received no optical stimulation during conditioning to further control for spontaneous preference shifts. Neither control group showed a significant CPP (Fig. 3E right, P > 0.5 by Student's t test). Furthermore, we did not find any significant changes in anxiety-related behaviors (Fig. 3G) or in locomotor activity (Fig. 3H) during preference tests and in open field tests (fig. S6).

Next, we tested whether the CPP effect observed was due to an appetitive effect from 50-Hz stimulation or to an aversive effect from 1-Hz stimulation. We compared the effect of each firing modality with no stimulation in two independent cohorts. Consistent with the previous CPP experiments (Fig. 3, E and F), the phasic cohort displayed significant place preference for the stimulation chamber after conditioning (Fig. 4, A and C), from 251 ± 28 s during pretest to 522 ± 63s during posttest (n = 7 mice; P < 0.05, Student's t test). However, the 1-Hz cohort (n = 6) showed no place aversion for the 1-Hz stimulation chamber (showing a trend toward place preference for 1 Hz instead; Fig. 4, B and C). We hypothesized that the CPP effect observed for the phasic cohort could be due to larger transient DA release triggered by the 50-Hz optical stimulation. We therefore used in vivo fast-scan cyclic voltammetry (FSCV) (16, 17) to detect DA transients. Maintaining the optical fiber in the VTA, we implanted a carbon fiber electrode for measuring DA signals in the NAc, one of the major targets of VTA DA projections (Fig. 1D). Despite sharing the same total illumination duration and number of light flashes (25 15-ms light flashes at 1 Hz or 50 Hz), the 50-Hz light train elicited larger DA transients (Fig. 4, D and E). Indeed, the mean peak DA transient concentrations in the NAc were measured at 75.9 ± 24.5 nM and 1.3 ± 0.8 nM, respectively, for the 50-Hz and 1-Hz stimuli (Fig. 4E); the former is similar to the magnitude of natural reward-triggered dopamine transients (16), whereas DA accumulation during chronic 1-Hz stimulation remained much lower (fig. S7; this level of DA could still theoretically contribute to behavioral changes).

Fig. 4.

Phasic DA neuron stimulation leads to transient DA release and place preference. (A and B) Effect of phasic (50 Hz) (A) and tonic (1 Hz) (B) stimulation on place preference. (Left) Time spent in each chamber during preference test. (Right) Comparison of preference scores; for A, n = 7, and for B, n = 6. *P < 0.05. (C) Relative effects of stimulation frequency examined by using the difference scores for phasic, tonic, and nonassociative control (same as No Stim in Fig. 3E) cohorts. (D) FSCV measurements of VTA stimulation–triggered transient DA release in NAc in anesthetized TH∷IRES-Cre mice. (Top) Representative voltammetry traces during phasic (25 flashes per 50 Hz) and tonic (16 flashes per 1 Hz) stimulation of VTA. (Insets) Background-subtracted voltammogram taken from the peak of stimulation, indicating that signal measured is DA on the basis of comparison to voltammograms of DA obtained in vitro. (Bottom) All background-subtracted voltammograms recorded over the 20-s interval. y axis is applied potential (Eapps versus Ag/AgCl reference electrode); x axis is the time at which each voltammogram was recorded. Current changes at the electrode are encoded in color. DA can be seen during stimulation at the feature ∼0.650 V (oxidation peak encoded as green) and between ∼−0.20 V and ∼−0.25 V at the end of the voltage scan. (E) Comparison of phasic and tonic light-evoked DA transients (n = 3).

Rodents learn to associate the effects of stimuli with their environment and subsequently display a conditioned place preference for that environment (18). Previous studies have demonstrated the important role of DA in the processing of salient signals (19) and goal-directed behaviors (20). However, it has been unclear whether other circuits and neurotransmitter systems are required at the same time (21) and whether specific patterns of activity in distinct neuron types are sufficient to effect place preference. To enable direct testing of the role of phasic DA neuron firing on behavioral conditioning, we developed a versatile Cre-inducible gene expression system to decouple the strength of transgene expression from cell type–specific promoters (which are often too weak to drive functional expression of opsins). By using this system, we selectively modulated DA neuron activity with defined stimulation patterns in the CPP paradigm and found that phasic stimulation sufficed to establish place preference in the absence of other reward. These results establish a causal role in behavioral conditioning for defined spiking modes in a specific cell type; of course, even a single cell type can release multiple neurotransmitters and neuromodulators (for example, VTA DA neurons primarily release DA but can also release other neurotransmitters such as glutamate) and will exert effects through multiple distinct downstream cell types. Indeed, the optogenetic approach, integrated with electro-physiological, behavioral, and electrochemical readout methods, opens the door to exploring the causal, temporally precise, and behaviorally relevant interactions of DA neurons with other neuromodulatory circuits (22–25), including monoaminergic and opioid circuits important in neuropsychiatric illnesses (26–28). In the process of identifying candidate interacting neuro-transmitter systems, downstream neural circuit effectors (29), and subcellular biochemical mechanisms on time scales appropriate to behavior and relevant circuit dynamics, it will be important to continue to leverage the specificity and temporal precision of optogenetic control (30).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Wightman, P. Phillips, and the entire Deisseroth laboratory for their support. All reagents and protocols are freely distributed and supported by the authors (www.optogenetics.org); because these tools are not protected by patents, Stanford University has applied for a patent to ensure perpetual free distribution to the international academic nonprofit community. H.C.T. is supported by a Stanford Graduate Fellowship. F.Z. and G.D.S. are supported by NIH National Research Service award. A.R.A. is supported by the Fonds National de la Recherche Scientifique, NARSAD, and the Fondation Leon Fredericq. L.d.L. is supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, and NARSAD. K.D. is supported by NSF; National Institute of Mental Health; NIDA; and the McKnight, Coulter, Snyder, Albert Yu and Mary Bechmann, and Keck foundations.

Footnotes

References and Notes

- 1.Wise RA. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:483. doi: 10.1038/nrn1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Everitt BJ, Robbins TW. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1481. doi: 10.1038/nn1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robinson TE, Berridge KC. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1993;18:247. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(93)90013-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koob GF, Le Moal M. Science. 1997;278:52. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5335.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schultz W. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2007;30:259. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.061604.135722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ungless MA, Magill PJ, Bolam JP. Science. 2004;303:2040. doi: 10.1126/science.1093360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang F, Larry C. Katz Memorial Lecture presented at the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Meeting on Neuronal Circuits; Cold Spring Harbor, NY. 13 to 16 March 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Atasoy D, Aponte Y, Su HH, Sternson SM. J Neurosci. 2008;28:7025. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1954-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boyden ES, Zhang F, Bamberg E, Nagel G, Deisseroth K. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1263. doi: 10.1038/nn1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nagel G, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:13940. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1936192100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Materials and methods are available as supporting material on Science Online.

- 12.Bjorklund A, Dunnett SB. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30:194. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu QS, Pu L, Poo MM. Nature. 2005;437:1027. doi: 10.1038/nature04050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robinson S, Smith DM, Mizumori SJ, Palmiter RD. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:13329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405084101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adamantidis AR, Zhang F, Aravanis AM, Deisseroth K, de Lecea L. Nature. 2007;450:420. doi: 10.1038/nature06310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Phillips PE, Stuber GD, Heien ML, Wightman RM, Carelli RM. Nature. 2003;422:614. doi: 10.1038/nature01476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stuber GD, et al. Science. 2008;321:1690. doi: 10.1126/science.1160873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tzschentke TM. Addict Biol. 2007;12:227. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2007.00070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cannon CM, Palmiter RD. J Neurosci. 2003;23:10827. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-34-10827.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grace AA, Floresco SB, Goto Y, Lodge DJ. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30:220. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hnasko TS, Sotak BN, Palmiter RD. J Neurosci. 2007;27:12484. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3133-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalivas PW. Am J Addict. 2007;16:71. doi: 10.1080/10550490601184142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Picciotto MR, Corrigall WA. J Neurosci. 2002;22:3338. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-09-03338.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dani JA, Bertrand D. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2007;47:699. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.47.120505.105214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harris GC, Aston-Jones G. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:865. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nestler EJ, Carlezon WA., Jr Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:1151. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williams J, Dayan P. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2005;15:160. doi: 10.1089/cap.2005.15.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Graybiel AM. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2008;31:359. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.112851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shen W, Flajolet M, Greengard P, Surmeier DJ. Science. 2008;321:848. doi: 10.1126/science.1160575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang F, et al. Nature. 2007;446:633. doi: 10.1038/nature05744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.