Abstract

Cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2D6 is an enzyme that is expressed in liver and brain. It can inactivate neurotoxins such as 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine, 1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline and β-carbolines. Genetically slow CYP2D6 metabolizers are at higher risk for developing Parkinson’s disease, a risk that increases with exposure to pesticides. The goal of this study was to investigate the neuroprotective role of CYP2D6 in an in-vitro neurotoxicity model. SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells express CYP2D6 as determined by western blotting, immunocytochemistry and enzymatic activity. CYP2D6 metabolized 3-[2-(N,N-diethyl-N-methylammonium)ethyl]-7-methoxy-4-methylcoumarin and the CYP2D6-specific inhibitor quinidine (1 μM) blocked 96 ± 1% of this metabolism, indicating that CYP2D6 is functional in this cell line. Treatment of cells with CYP2D6 inhibitors (quinidine, propanolol, metoprolol or timolol) at varying concentrations significantly increased the neurotoxicity caused by 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium (MPP+) at 10 and 25 μM by between 9 ± 1 and 22 ± 5% (P < 0.01). We found that CYP3A is also expressed in SH-SY5Y cells and inhibiting CYP3A with ketoconazole significantly increased the cell death caused by 10 and 25 μM of MPP+ by between 8 ± 1 and 30 ± 3% (P < 0.001). Inhibiting both CYP2D6 and CYP3A showed an additive effect on MPP+ neurotoxicity. These data further support a possible role for CYP2D6 in neuroprotection from Parkinson’s disease-causing neurotoxins, especially in the human brain where expression of CYP2D6 is high in some regions (e.g. substantia nigra).

Keywords: AMMC, cytochrome P450 2D6, cytochrome P450 3A, MPP+, MPTP, Parkinson’s disease, SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a neurodegenerative disorder in which both genetic (e.g. Parkin and Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2) and environmental (e.g. pesticides) risk factors have been implicated in the etiology (Di Monte, 2003; Olanow, 2007). One genetic factor associated with a predisposition to injury from exogenous toxins is the drug- and toxin-metabolizing enzyme cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2D6 (McCann et al., 1997). Genetic association studies show that poor metabolizers of CYP2D6, those lacking a functional enzyme, have an increased risk for PD (McCann et al., 1997). This risk is further elevated when these individuals are exposed to pesticides (Deng et al., 2004; Elbaz et al., 2004). This suggests that having inactive CYP2D6 makes individuals more susceptible to the effects of environmental neurotoxins, such as pesticides, which is probably due to their inability to inactivate these neurotoxins.

Cytochrome P450 2D6 is a drug- and toxin-metabolizing enzyme that can inactivate a number of neurotoxins including 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) (Modi et al., 1997), tetra-hydroisoquinolines (Suzuki et al., 1992), harmaline, harmine (Yu et al., 2003) and N-methyl-β-carbolines (Herraiz et al., 2006). CYP2D6 is found in the liver and in peripheral tissues including the brain (Miksys et al., 2002; Mann et al., 2008), where it has been shown to be enzymatically functional (Strobel et al., 1995; Tyndale et al., 1999; Voirol et al., 2000; Bromek et al., 2009). In-situ inactivation of MPTP to PTP was shown in rat striatum, a reaction largely mediated by CYP2D by N-demethylation (Coleman et al., 1996; Vaglini et al., 2004; Herraiz et al., 2006). The expression of CYP2D6 is brain region and cell type specific and also exhibits high interindividual variability (Miksys et al., 2002; Mann et al., 2008). In primates, CYP2D protein levels are highest in the basal ganglia, especially the substantia nigra (Miksys et al., 2002; Mann et al., 2008), consistent with data in rat brain (Bromek et al., 2009). In fact, in the substantia nigra, CYP2D co-localizes with tyrosine hydroxylase, a marker for dopaminergic neurons (Watts et al., 1998). CYP2D6 is also found in glial cells (Miksys et al., 2000) that can also express the neurotoxin-activating enzyme monoamine oxidase B (Nicotra & Parvez, 2000; Herraiz et al., 2007). Thus, CYP2D6 is ideally situated in cells and brain regions to locally detoxify PD-causing agents.

In a rodent model, a study comparing the toxicity of MPTP in different rat strains found that female Dark Agouti rats (models of poor metabolizers of CYP2D) showed more pronounced effects of MPTP and a longer reduction of motor activity compared with other strains (Jimenez-Jimenez et al., 1991). Consistent with this, over-expression of CYP2D6 in PC12 cells was shown to protect against 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium (MPP+) cytotoxicity (Matoh et al., 2003). Together, this evidence suggests that the expression of functional CYP2D6 may provide a defense against endogenous and/or exogenous neurotoxins. Given the lack of direct evidence for the involvement of CYP2D6 in neuroprotection, we proposed to test the importance of endogenous CYP2D6 in protecting against MPTP/MPP+ neurotoxicity in SH-SY5Y cells. The goals of the current study were to (i) determine whether human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells express functional CYP2D6 and (ii) investigate the direct contribution of endogenous CYP2D6 to protection against MPP+-induced neurotoxicity in this neuronal cell line using CYP2D6 inhibitors.

Materials and methods

Materials

The protein assay dye reagent was purchased from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, CA, USA). Pre-stained molecular weight protein markers were purchased from MBI Fermentas (Flamborough, ON, Canada). Nitrocellulose membrane was purchased from Pall Life Sciences (Pensacola, FL, USA). Human cDNA-expressed CYP1A2, CYP2D6, CYP3A4, 3-[2-(N,N-diethylamino)ethyl]-7-hydroxy-4-methylcoumarin hydrochloride and the 3-[2-(N,N-diethyl-N-methylammonium)ethyl]-7-methoxy-4-methylcoumarin (AMMC) high-throughput inhibitor screening kit were purchased from BD Biosciences (Mississauga, ON, Canada). Polyclonal antibody (PAb) raised in rabbit against amino acids 254–273 of CYP2D6 was a gift from A. Cribb and Merck & Co. (Whitehouse Station, NJ, USA) (Cribb et al., 1995; Miksys et al., 2002). CYP1A2 PAb raised in rabbit was purchased from Affinity Bio-Reagents (Golden, CO, USA). CYP3A4 monoclonal antibody was purchased from Diachii Pure Chemicals Co., Ltd (Tokyo, Japan). Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit and anti-mouse secondary antibodies raised in goat were purchased from Chemicon International, Inc. (Temecula, CA, USA). Avidin–biotin complex with peroxidase kit and 3,3′-diam-inobenzidine were purchased from Vector Laboratories (Burlington, ON, Canada). Chemiluminescent substrate was purchased from Pierce Chemical Company (Rockford, IL, USA). Autoradiographic film was purchased from Ultident Scientific (St Laurent, PQ, Canada). T-175-cm2 vented cap cell culture flasks were from Sarstedt (Newton, USA). SH-SY5Y cells and the 3-(3,4-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltet-razolium bromide (MTT) assay kit were from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). Roswell Park Memorial Institute + L-glutamine was purchased from Invitrogen (Burlington, ON, Can-ada). MPTP, MPP+, quinidine, propanolol, metoprolol and timolol were purchased from Sigma (Mississauga, ON, Canada).

Cell culture

The SH-SY5Y cells were cultured in 175-cm2 flasks in Roswell Park Memorial Institute + L-glutamine with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 50 U/mL penicillin and 50 mg/mL streptomyocin in a humidified, 5% CO2, 37°C incubator. The medium was changed every second day and cells were subcultured at ~80% confluency every 4–5 days using 0.1% trypsin. Passages 2–15 were used for all experiments. For immunocytochemistry, cells were cultured at 2 × 104 cells/well onto poly-D-lysine-coated glass coverslips in six-well plates. For the MTT assay, cells were cultured at 1 × 104 cells/-well in 96-well plates. SH-SY5Y cells cultured in 175-cm2 flasks were harvested and lysed in ice-cold Tris (100 mM, pH 7.4), EDTA (0.1 mM) and dithiothreitol (0.1 mM) buffer and sonicated on ice twice for 10 s. The samples were then either used for western blotting or further purified for activity assays. For activity, cell homogenates were centrifuged at 3000 g for 10 min at 4°C. The pellet was resuspended and centrifuged again at 3000 g for 10 min at 4°C. The combined supernatants were centrifuged at 110 000 g for 90 min at 4°C and the pellet resuspended in 100 mM Tris, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM dithiothreitol, 1.15% w/v KCl and 20% v/v glycerol. The protein content of the membranes was assayed with the Bradford technique using a Bio-Rad Protein Assay kit. Membranes were either used directly for activity or aliquoted and stored at −80°C.

Western blotting

The SH-SY5Y whole-cell lysates and cDNA-expressed CYP2D6, CYP1A2 and CYP3A4 were serially diluted to generate standard curves. These standard curves were used to determine the linear detection range and relative amount of each CYP (pmol/μg of whole-cell lysate protein) expressed in SH-SY5Y cells. Samples were separated by using sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis with 8% separating and 4.5% stacking gels. The proteins were transferred overnight onto nitrocellulose membranes and blocked with 2% w/v skim milk powder in Tris-Buffered Saline Tween-20 (0.1% bovine serum albumin, 0.1% Triton X-100, 50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4). The CYP2D6 PAb used was specific for CYP2D6, based on its lack of cross-reactivity with other human CYPs (Cribb et al., 1995). The blot was probed with CYP2D6 PAb diluted 1 : 3000, CYP3A4 PAb diluted 1 : 4000 or CYP1A2 monoclonal antibody diluted 1 : 10 000 in TBS-T, followed by peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit or anti-mouse secondary antibody diluted 1 : 3000 or 1 : 17 000, respectively, in TBS-T. Protein was then detected using chemiluminescence. As three different antibodies were used, exposure times varied from 45 s to 5 min for optimal band detection on autoradiographic film. MCID Elite imaging software (Interfocus Imaging Ltd, Linton, UK) was used to analyze the films.

Immunocytochemistry

Cells were grown on poly-D-lysine-coated glass coverslips, blocked for 1 h in 1% w/v skimmed milk, 1% w/v bovine serum albumin, 2% v/v normal horse serum and 0.01% v/v Triton X-100 in phosphate-buffered saline, and then incubated for 48 h at 4°C in CYP2D6 PAb at 1 : 500 in phosphate-buffered saline with 0.1% bovine serum albumin and 2% normal horse serum. The antigen–antibody complex was visualized using biotinylated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin (diluted 1 : 500 in phosphate-buffered saline) followed by the avidin–biotin complex technique and reaction with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine and hydrogen peroxide. Negative control sections were incubated in the same manner but without primary antibody.

Conditions for in-vitro metabolism of 3-[2-(N,N-diethyl-N-methylammonium)ethyl]-7-methoxy-4-methylcoumarin by CYP2D6

The CYP2D6 activity in SH-SY5Y cell membranes was determined by using the specific substrate AMMC (Yamamoto et al., 2003) high-throughput assay screening kit in 96-well microplates. AMMC activity assays were performed as instructed by the kit manufacturer (Gentest, BD Biosciences). In brief, 100 μL of buffer containing a NADPH-regenerating system (with final concentrations of 0.013 mM NADP+, 0.6 mM MgCl2, 0.6 mM glucose-6-phosphate and 0.3 U/mL glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase) was added to each well. To assess if the metabolism of AMMC was specifically mediated by CYP2D6, a selective CYP2D6 inhibitor, quinidine (0.1–10 μM), was added. The plate was warmed to 37°C for 15 min, followed by the addition of 100 μL of 0.5 M potassium phosphate (pH 7.4) buffer containing AMMC (1.5–5 μM). The reaction was initiated by the addition of pre-warmed cDNA-expressed CYP2D6 (1–8 pmol) or SH-SY5Y membranes (50 μg). The plate was then incubated at 37°C for 30 min and the reaction stopped using 75 μL of 0.5 mM Tris base. The fluorescence signal was measured using a SpectroMax Gemini EM (Molecular Devices) fluorescence plate reader at excitation and emission wavelengths of 390 and 450 nm, respectively. 3-[2-(N,N-diethyl-amino)ethyl]-7-hydroxy-4-methylcoumarin hydrochloride (0.03–1000 nM) in buffer was used as the standard for metabolite quantification as recommended for the kit. We confirmed that the fluorescence from quinidine did not interfere with the assay by adding quinidine (0.01–10 μM) to wells with buffer alone. To determine background fluorescence, control wells had enzyme, buffer (with or without inhibitor) and AMMC added after the addition of the stop solution. Specific fluorescence due to AMMC metabolism was determined by subtraction of the fluorescence from these background control wells from the sample fluorescence. In experiments measuring AMMC metabolism by SH-SY5Y cells, positive control wells contained cDNA-expressed CYP2D6 (2 pmol) plus or minus quinidine (1 μM).

Drug treatments and 3-(3,4-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide assay

Cells were cultured in 96-well plates for 1 day and then pre-treated at 37°C for 30 min with the CYP2D6 inhibitors quinidine (0.01–10 μM), metoprolol (1–100 μM), propanolol (0.1–30 μM), timolol (1–300 μM) or the CYP3A inhibitor ketoconazole (0.0001–10 μM). The cells were treated with MPTP (0.1–3 mM) or MPP+ (0.01–1 mM) in the continued presence of inhibitors for 48 h and then assessed for cell viability. Cell viability was determined by a mitochondrial enzyme-dependent reaction of MTT assay as described by the manufacturer. In brief, 10 μL of MTT was added directly to the culture media with the SH-SY5Y cells. Following a 2-h incubation at 37°C, 100 μL of solubilizing agent was added to dissolve the purple formazan crystals formed by metabolism of the yellow MTT tetrazolium salt. The plate was then incubated for 1 h, or overnight, and the absorbance was measured using the Multiskan Ex (Thermo Electron Co.) plate reader at a wavelength of 570 nm. Cell death following MPP+ treatment was shown as a percentage of untreated cells. To determine the effect of the inhibitors alone on cell death, cells were treated with each inhibitor at each dose tested in the absence of MPP+.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using the Self-Propelled Semi-Submersible analytical program (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). The comparison of the CYP2D6 metabolism of AMMC in the presence and absence of inhibitor was evaluated using a directional Student’s t-test. The effect of CYP inhibition on MPTP/MPP+ neurotoxicity was compared with MPTP/MPP+-treated cells without inhibitor, using one-way ANOVA followed by a least significant difference post-hoc test. To determine an additive effect of inhibiting both CYP2D6 and CYP3A, a two-way ANOVA was used to test for an interaction between ketoconazole and quinidine on MPP+ neurotoxicity. This was followed by a one-way ANOVA and least significant difference post-hoc test to compare the effects of drug treatments with one another.

Results

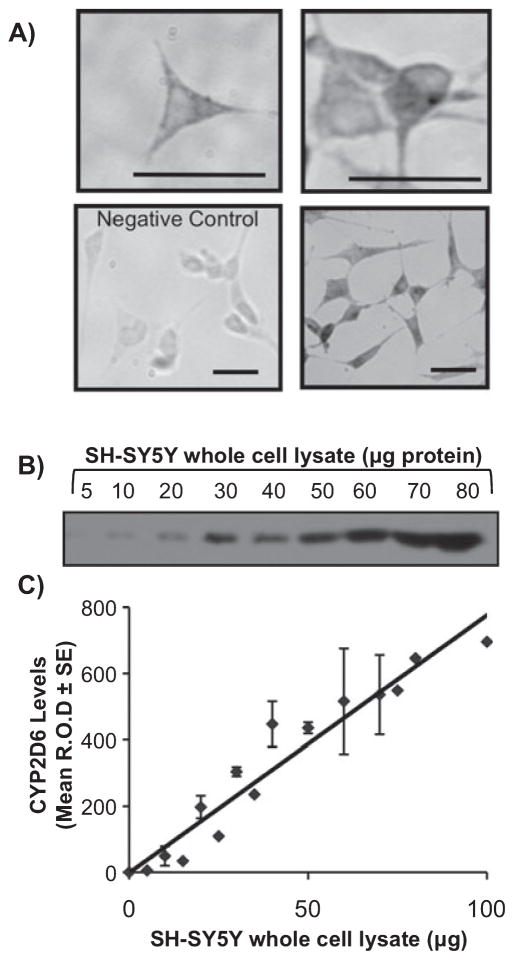

SH-SY5Y cells express CYP2D6 protein

Immunocytochemistry indicated that CYP2D6 is expressed throughout the cell including neuronal projections (Fig. 1A), consistent with in-situ neuronal expression (Miksys et al., 2002; Mann et al., 2008). Some partial staining of the nucleus was also seen in negative control cells incubated without primary antibody (Fig. 1A, bottom left). To quantitatively assess CYP2D6 expression by western blotting, a dilution curve was generated using SH-SY5Y whole-cell lysates (Fig. 1B). CYP2D6 protein detection (Fig. 1C) was linear up to 80 μg of SH-SY5Y whole-cell lysate protein and, using a standard curve of cDNA-expressed CYP2D6, it was determined SH-SY5Y cells express 0.29 ± 0.03 pmol of CYP2D6/μg of whole-cell lysate protein.

Fig. 1.

SH-SY5Y cells express CYP2D6 protein. (A) CYP2D6 immunohistochemical labeling throughout SH-SY5Y cells. Negative control (bottom left) shows partial staining of the nucleus in the absence of primary antibody. (B) A representative immunoblot of CYP2D6 detection in increasing amounts of whole-cell lysate protein. (C) A standard curve of CYP2D6 expression [relative optical density (R.O.D.)] in SH-SY5Y cells showing linear detection. Mean band density ± SEM from four western blots. Bar = 100 μm.

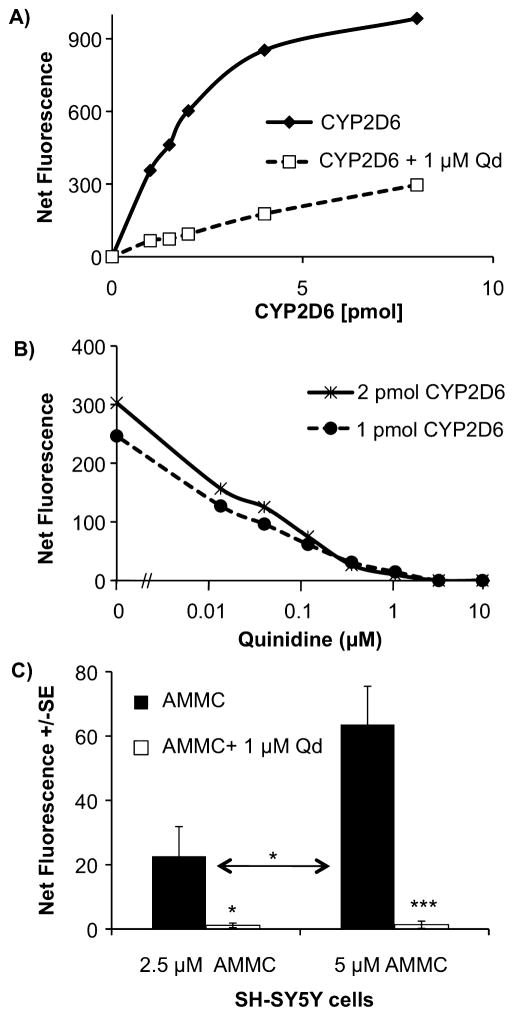

CYP2D6 in SH-SY5Y cells is enzymatically active

The metabolism of AMMC to its fluorescent product 3-[2-(N,N-diethyl-N-methyl-ammonium)ethyl]-7-hydroxy-4-methylcoumarinwas dependent on the amount of cDNA-expressed CYP2D6 protein and was inhibited by quinidine (1 μM) (Fig. 2A). Quinidine dose-dependently inhibited AMMC metabolism by cDNA-expressed CYP2D6 (Fig. 2B). In agreement with the literature, quinidine at its Ki (0.01 μM) (Bertelsen et al., 2003) inhibited ~50% of AMMC metabolism with complete inhibition at 1 μM or higher. SH-SY5Y cell membranes dose-dependently metabolized AMMC (Fig. 2C), which was completely inhibited by quinidine (1 μM) (P < 0.001). We confirmed that fluorescence from quinidine did not interfere with the assay by adding quinidine (0.01–10 μM) to wells with buffer alone. These results demonstrate a functional CYP2D6 enzyme in SH-SY5Y cells, which can be inhibited by the CYP2D6-specific inhibitor quinidine.

Fig. 2.

AMMC metabolism by cDNA-expressed CYP2D6 and SH-SY5Y cells. (A) Metabolism of AMMC (1.5 μM) is cDNA-expressed CYP2D6 protein dependent and is inhibited by 1 μM of quinidine (Qd). (B) Quinidine dose-dependently inhibited cDNA-expressed CYP2D6 metabolism of AMMC (1.5 μM). (C) Metabolism of 2.5 and 5 μM AMMC by SH-SY5Y cell membranes (50 μg) in the absence and presence of quinidine (1 μM). Mean ± SEM of two experiments (N = 3 wells/experiment). Results are shown as sample fluorescence with background fluorescence subtracted. Student’s t-test, *P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

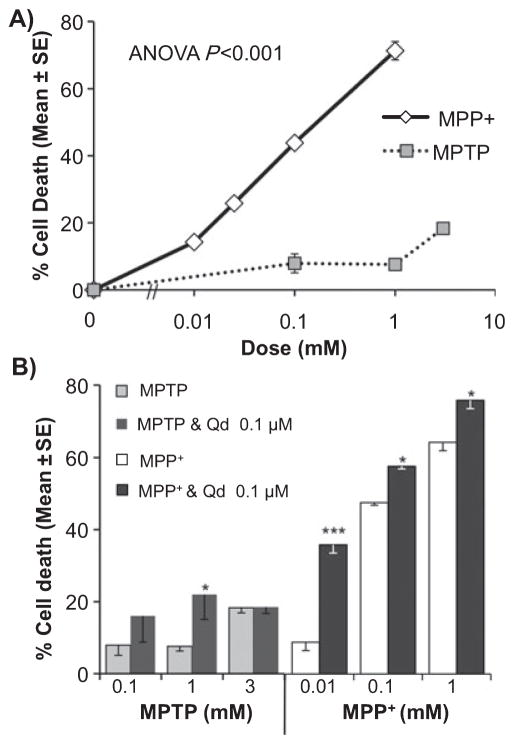

1-Methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine and 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium neurotoxicity

Both MPTP and MPP+ induced significant cell death (ANOVA, P < 0.001) in SH-SY5Y cells (Fig. 3A). MPP+ showed a dose-dependent effect on cell death. At the highest dose tested, MPTP (3 mM) showed 18 ± 1% cell death compared with 71 ± 3% by MPP+ (1 mM). MPP+ caused 18% cell death at ~0.015 mM, suggesting that MPP+ is 200 times more potent than MPTP in this cell line. Quinidine (0.1 μM) significantly increased cell death by MPP+ at all doses and at 1 mM of MPTP (Fig. 3B). For subsequent experiments, 48 h exposure to MPP+ at low doses was used instead of MPTP because (i) MPP+ was more potent at causing neurotoxicity and (ii) MPP+ was significantly affected by 0.1 μM of quinidine (which specifically targets CYP2D6).

Fig. 3.

MPTP and MPP+ neurotoxicity in SH-SY5Y cells. (A) Dose response of 48-h exposure to MPTP and MPP+ on cell death. (B) The effects of CYP2D6 inhibition by quinidine (Qd) (0.1 μM) on MPTP and MPP+ neurotoxicity. Mean of three wells per toxicity group ± SEM. Results are shown as percent cell death caused by inhibitor alone subtracted from percent cell death observed with inhibitor plus MPP+. Quinidine (0.1 μM) had no effect on cell death without MPP+. One-way ANOVA and least significant difference post-hoc test, *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001.

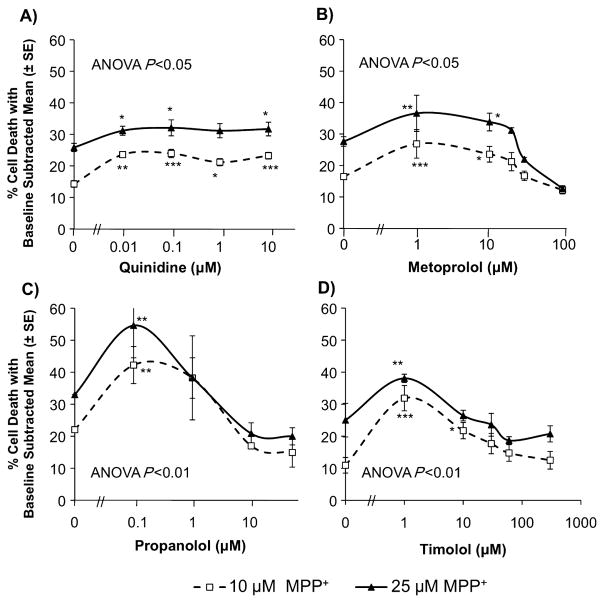

Inhibiting CYP2D6 increases 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium-induced neurotoxicity

Quinidine (Fig. 4A) significantly enhanced cell death (4 ± 1 to 9 ± 1%) caused by MPP+ at 10 and 25 μM (P < 0.05). To confirm the effects of inhibiting CYP2D6 on MPP+ neurotoxicity, three other CYP2D6 inhibitors (which are not substrates or inhibitors of CYP3A) were tested (Chauret et al., 2001; Yamamoto et al., 2003). Metoprolol (Fig. 4B), propanolol (Fig. 4C) and timolol (Fig. 4D) significantly increased MPP+-induced cell death by 8 ± 2 to 22 ± 5% (P < 0.05). There was no effect of quinidine or timolol alone on neurotoxicity; however, metoprolol alone increased cell death by 5 ± 2 to 7 ± 1% and propanolol alone increased cell death by 5 ± 5 to 21 ± 3%. The results in Fig. 4 are shown as the difference between percent cell death caused by inhibitor plus MPP+ and inhibitor alone, where percent cell death observed with inhibitor alone was subtracted from percent cell death observed with inhibitor plus MPP+.

Fig. 4.

The effect of CYP2D6 inhibition on MPP+ neurotoxicity. There was a significant increase in MPP+ neurotoxicity in the presence of (A) quinidine (by 4 ± 1 to 9 ± 1%), (B) metoprolol (by 8 ± 2 to 11 ± 6%), (C) propanolol (by 20 ± 3 to 22 ± 5%) and (D) timolol (by 13 ± 1 to 21 ± 4%). Results are shown as percent cell death caused by inhibitor alone (baseline) subtracted from percent cell death observed with inhibitor plus MPP+. Quinidine and timolol had no effect on cell death without MPP+. Metoprolol increased cell death by 7 ± 1% (1 μM) and by 5 ± 2% (10–100 μM) without MPP+. Propanolol increased cell death by 7 ± 25% (0.1 μM), 5 ± 5% (1 μM), 16 ± 1% (10 μM) and 21 ± 3% (50 μM) without MPP+. Mean of triplicate wells from two to four experiments ± SEM. One-way ANOVA and least significant difference post-hoc test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

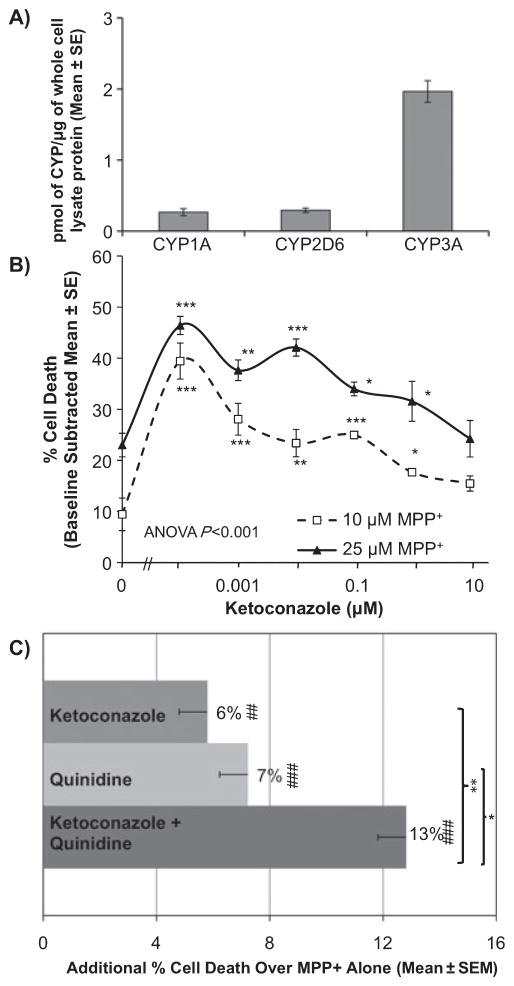

Influence of CYP3A and CYP2D6 in 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium-induced neurotoxicity

As CYP3A and CYP1A2 can also inactivate neurotoxins (Coleman et al., 1996; Gilham et al., 1997), their effect in our in-vitro MPP+ neurotoxicity model was tested. Figure 5A shows the relative levels of CYP1A (0.26 ± 0.05 pmol), CYP2D6 (0.29 ± 0.03 pmol) and CYP3A (2.0 ± 0.1 pmol) expression/μg of SH-SY5Y whole-cell lysate protein, determined by comparison with their respective cDNA-expressed CYP standard curves. As CYP3A had higher expression than both CYP2D6 and CYP1A, we assessed the influence of CYP3A activity on MPP+ neurotoxicity by using an inhibitor of CYP3A, ketoconazole (Bourrie et al., 1996). Inhibiting CYP3A significantly (ANOVA, P < 0.001) increased cell death by MPP+ (Fig. 5B). Low and selective doses of ketoconazole (0.0001–0.1 μM) significantly enhanced MPP+-induced (10 and 25 μM) cell death by 14 ± 2 to 30 ± 3%. To determine the relative influence of CYP2D6 and CYP3A on MPP+ neurotoxicity, both inhibitors were administered together or alone at doses close to their corresponding Ki established in human liver microsomes (Bourrie et al., 1996) (Fig. 5C). Both ketoconazole (6 ± 1%) and quinidine (7 ± 2%) significantly increased MPP+-induced cell death compared with no inhibitor (P < 0.01). Co-treatment with ketoconazole and quinidine showed an additive effect (13 ± 2%) on MPP+-induced neurotoxicity. Ketoconazole alone, quinidine alone and ketoconazole plus quinidine without MPP+ had no effect on cell death. There was a significant effect of quinidine (P < 0.001) and ketoconazole (P < 0.001) on MPP+ neurotoxicity but no significant interaction between the two drugs (two-way ANOVA, P = 0.64, F = 0.23). This suggests that both CYP2D6 and CYP3A independently influence MPP+ neurotoxicity in SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells.

Fig. 5.

The role of CYP2D6 and CYP3A in MPP+ neurotoxicity. (A) SH-SY5Y cells express CYP1A, CYP2D6 and CYP3A at 0.26 ± 0.05, 0.29 ± 0.03 and 2.0 ± 0.1 pmol/μg of whole-cell lysate protein, respectively. Mean band density ± SEM from three or four western blots. (B) The effects on MPP+ neurotoxicity of inhibiting CYP3A with ketoconazole. Ketoconazole increased cell death in the presence of MPP+. Results are shown as percent cell death minus baseline cell death of inhibitor-treated cells with no MPP+. One-way ANOVA and least significant difference post-hoc test, *P < 0.01, **P < 0.005, ***P < 0.0001. (C) The effects on MPP+ (10 μM)-induced cell death of inhibiting CYP3A and CYP2D6, alone and together with their respective specific inhibitors ketoconazole (0.001 μM) and quinidine (0.1 μM). Results are derived from percent cell death caused by inhibitor alone (baseline) subtracted from percent cell death observed with inhibitor plus MPP+. Ketoconazole alone, quinidine alone and ketoconazole plus quinidine without MPP+ had no effect on cell death. One-way ANOVA and LSD post-hoc test, *P < 0.01, **P < 0.005 compared with inhibitor treatments and ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.005 compared with MPP+ treatment alone. Mean of triplicate wells from three experiments ± SEM.

Discussion

Here we show for the first time that endogenous CYP2D6 metabolic activity directly influences MPP+ neurotoxicity in living cells. The detection of enzymatically functional CYP2D6 protein in SH-SY5Y cells confirms data suggesting that these cells contain CYP2D6 assessed by the metabolism of [3H]-codeine to morphine, a pathway mediated primarily by CYP2D6 (Poeaknapo et al., 2004; Boettcher et al., 2005). We showed that quinidine not only increases neurotox-icity caused by MPTP but also that caused by the neurotoxic metabolite MPP+. More importantly, in addition to quinidine, three other CYP2D6-selective inhibitors (Yamamoto et al., 2003) at low concentrations lead to a significant 9–20% enhancement in cell death caused by MPP+ alone. This suggests that by inhibiting CYP2D6 we reduced its ability to inactivate this neurotoxin, thereby increasing cell death.

1-Methyl-4-phenylpyridinium can competitively inhibit the metabolism of CYP2D6-specific substrates in liver and brain microsomes (Fonne-Pfister et al., 1987; Jolivalt et al., 1995). Docking studies indicate that the methyl group of MPTP fits into the active site of CYP2D6 (Modi et al., 1997) and CYP2D6 tends to interact with positively charged amines (Yao et al., 2004), suggesting a role for CYP2D6 in the demethylation of both MPTP and MPP+. Although direct evidence for inactivation of MPP+ by CYP2D6 is lacking, our study in a human neuronal cell line supports this idea. In agreement with our findings, the CYP2D6 inhibitor fluoxetine (Bertelsen et al., 2003) increased MPP+ cytotoxicity in PC12 rat pheochromocytoma cells (Han & Lee, 2009). In addition, over-expression of CYP2D6 in PC12 cells was shown to be protective against MPP+-induced cytotoxicity (Matoh et al., 2003). Together this indicates that CYP2D6 can play a neuroprotective metabolic role against MPTP and MPP+ neurotoxicity, by increasing inactivation of MPTP and possibly MPP+. Moreover, higher levels of functional CYP2D6 may be important in protecting individuals from PD-causing neurotoxins.

Genetically variable CYP2D6 is highly polymorphic (http://www.cypalleles.ki.se/cyp2d6.htm) and has large variability in brain expression, which is probably amplified by environmental inducers/inhibitors of CYP2D6. Liver CYP2D6 is genetically variable but essentially uninducible (Edwards et al., 2003); there is large variability in the expression and activity reported in human liver microsomes, e.g. metabolic inactivation of MPTP by CYP2D6 is shown to range from 0 to 90% (Coleman et al., 1996; Gilham et al., 1997). The large variation in CYP2D6 protein levels (influenced mostly by genetics) may make some individuals more or less prone to the effects of neurotoxins. Individuals who are genetically poor metabolizers of CYP2D6 are at increased risk of developing PD (McCann et al., 1997), especially when exposed to pesticides (Deng et al., 2004; Elbaz et al., 2004). Pesticides such as carbaryl, atrazine, diazinon, chlorpyrifos and parathion can be metabolized by CYP2D6 (Lang et al., 1997; Sams et al., 2000; Hodgson, 2001; Tang et al., 2002). In the brain, where expression of CYP2D6 is relatively high compared with other CYPs [e.g. CYP3A4 and CYP1A2 (Dutheil et al., 2009)], CYP2D6 may play a role in the localized elimination of pesticides. Thus, CYP2D6 may represent a link between genetic and environmental factors that influences the development of PD, especially as this enzyme is ideally localized in brain regions and cells affected in PD. If the degree of toxicity is determined, at least in part, by a balance between activation (e.g. by monoamine oxidase) and inactivation (e.g. by CYP2D6) of neurotoxins (Herraiz et al., 2006), then genetically higher or induced levels of brain CYP2D6 could increase neurotoxin inactivation and compete with neurotoxin activation.

Smokers display a 50% reduced risk of developing PD (Alves et al., 2004). We have shown that smokers have higher brain CYP2D6 than non-smokers (Mann et al., 2008) and these higher CYP2D6 levels may be partially responsible for the protection against PD observed in smokers. Nicotine, a component of cigarette smoke, has been shown to be neuroprotective (O’Neill et al., 2002; Quik et al., 2006; Singh et al., 2009) and it induces brain CYP2D in mice (Singh et al., 2009), rat (Yue et al., 2008) and monkey (Mann et al., 2008) with no change in liver CYP2D. In fact, similar to smokers, nicotine significantly increases CYP2D in regions affected in PD like the substantia nigra and striatum (Mann et al., 2008; Singh et al., 2009). Collectively, these data suggest that nicotine in cigarette smoke may be responsible for a smoker’s decreased risk of developing PD, perhaps in part through inducing brain, but not liver, CYP2D6.

Recently, in an MPTP-induced PD mouse model, nicotine was shown to reduce MPP+ levels in the striatum (Singh et al., 2009), which is consistent with an induction by nicotine of striatal CYP2D with a subsequent increase in MPTP and/or MPP+ deactivation. Nicotine was also shown to cause a recovery of CYP2D mRNA and activity that had been lost with MPTP treatment, probably through the induction of CYP2D. The ability of nicotine to induce brain CYP2D may be of benefit in PD, reducing further neuronal damage from toxins. It is also possible that higher levels of CYP2D may assist in maintaining dopaminergic tone as CYP2D can synthesize dopamine (Hiroi et al., 1998; Bromek et al., 2009), although an effect of CYP2D activity on dopamine levels in vivo has not yet been demonstrated. The ability to alter brain CYP2D6 expression may be important, especially as hepatic CYP2D6 is generally uninducible (Edwards et al., 2003). Given the punctate region- and cell-specific expression of CYP2D6, small changes in expression may have a large effect in localized toxin inactivation and neurotoxicity.

Consistent with higher CYP2D6 being protective (Matoh et al., 2003), our current study showed that inhibiting CYP2D6 enhanced MPP+ neurotoxicity. Quinidine at low concentrations was less effective at increasing MPP+-induced neurotoxicity than the other three CYP2D6 inhibitors, despite observing complete inhibition of AMMC metabolism in SH-SY5Y cell membranes with 1 μM quin-idine. This lower than expected effect of quinidine on MPP+ neurotoxicity may be due to the removal of quinidine by CYP3A as it is a substrate for CYP3A4 (Nielsen et al., 1999). It may also be due to the ability of quinidine to potently inhibit transporter systems such as Oct-3 (extraneuronal monamine transporter) (Liou et al., 2007) and vesicular monoamine transporter (Staal et al., 2001) that transport MPP+. Transporter expression is not well characterized in SH-SY5Y cells but these cells do express vesicular monoamine transporter (Fong et al., 2007). Therefore, quinidine may compete with transporters of MPP+, preventing its influx and reducing the toxic effects of MPP+, thereby attenuating the effect of quinidine on increasing neurotoxicity through inhibition of CYP2D6 MPP+ inactivation. Alternatively, the reduced MPP+ neurotoxicity at high concentrations of timolol, propanolol and metoprolol (β-blockers) may be through the blockade of Na+ and Ca2+channels and/or via adrenergic receptors (Goto et al., 2002). Timolol and other β-adrenergic antagonists have been shown to be neuroprotective against glutamate-induced toxicity in retinal ganglion cells (Goto et al., 2002; Wood et al., 2003).

The SH-SY5Y cells are very useful for modeling PD in vitro (Presgraves et al., 2004; McMillan et al., 2007); however, they do not entirely reflect the intact brain and its variable composition of activating (e.g. monoamine oxidase) and inactivating (e.g. CYP2D6) enzymes. In these cells, we found higher CYP3A expression than CYP2D6, whereas in the brain, the expression and activity of CYP3A are much lower than CYP2D6 and below detection in some regions (Voirol et al., 2000; Dutheil et al., 2009). A direct comparison of the inhibition of MPTP (50 μM) metabolic inactivation using quinidine (CYP2D6), ketoconazole (CYP3A) or furafylline (CYP1A2) in nine human CYP2D6 extensive metabolizer livers indicated that CYP2D6 was the main enzyme involved (54%), with minor contributions from CYP1A2 (32%) and CYP3A4 (12%) (Coleman et al., 1996); the relative contribution of CYP2D6 and CYP1A2 was subsequently replicated (Gilham et al., 1997). These data are consistent with the higher affinity of yeast-expressed CYP2D6 (Km = 39 μM) compared with CYP1A2 (Km = 2.2 mM) for MPTP (Coleman et al., 1996). At substantially higher concentrations of MPTP (2 mM), CYP1A2 and CYP3A4 contributed 49 and 25% of the inactivation, respectively (Coleman et al., 1996) suggesting that, like CYP1A2, CYP3A4 may have a lower affinity for MPTP than CYP2D6. Although these studies investigated MPTP inactivation, the same relative enzymatic contributions to MPP+ inactivation may occur given the structural resemblance of the two substrates; this, however, has not yet been demonstrated. Thus, compared with our results in SH-SY5Y cells, the impact of CYP2D6 may be much greater in the human brain compared with CYP3A due to the higher brain expression of CYP2D6 and its potential for higher rates of neurotoxin metabolic inactivation.

In conclusion, SH-SY5Y cells express enzymatically functional CYP2D6. Upon inhibiting this enzyme there is a 9–20% enhancement of MPP+-induced neurotoxicity, suggesting that this enzyme contributes importantly to protection against PD-causing neurotoxins. In addition, because nicotine treatment can increase CYP2D6 in the brain, this offers a potential therapeutic approach to protecting the brain from neurotoxins that are also substrates of CYP2D6.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this work was provided by the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, CIHR Grant (MOP97751) and a Canada Research Chair in Pharmacogenetics to R.F.T. Additional support was provided by a CIHR Tobacco Use in Special Populations Fellowship and Strategic Training Program in Tobacco Research to A.M. R.F.T. has shares in Nicogen Research Inc. Funds were not received from Nicogen for these studies and nor was this manuscript reviewed by individuals associated with Nicogen. We would like to thank Dr Sharon Miksys, Ewa Hoffmann and Nael Al Koudsi for their support and experimental advice and assistance.

Abbreviations

- AMMC

3-[2-(N,N-diethyl-N-methylammonium)ethyl]-7-methoxy-4-methyl-coumarin

- CYP

cytochrome P450

- MPP+

1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium

- MPTP

1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine

- MTT

3-(3,4-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- PAb

polyclonal antibody

- PD

Parkinson’s disease

References

- Alves G, Kurz M, Lie SA, Larsen JP. Cigarette smoking in Parkinson’s disease: influence on disease progression. Mov Disord. 2004;19:1087–1092. doi: 10.1002/mds.20117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertelsen KM, Venkatakrishnan K, Von Moltke LL, Obach RS, Greenblatt DJ. Apparent mechanism-based inhibition of human CYP2D6 in vitro by paroxetine: comparison with fluoxetine and quinidine. Drug Metab Dispos. 2003;31:289–293. doi: 10.1124/dmd.31.3.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boettcher C, Fellermeier M, Boettcher C, Drager B, Zenk MH. How human neuroblastoma cells make morphine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:8495–8500. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503244102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourrie M, Meunier V, Berger Y, Fabre G. Cytochrome P450 isoform inhibitors as a tool for the investigation of metabolic reactions catalyzed by human liver microsomes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;277:321–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromek E, Haduch A, Daniel WA. The ability of cytochrome P450 2D isoforms to synthesize dopamine in the brain: an in vitro study. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;626:171–178. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.09.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauret N, Dobbs B, Lackman RL, Bateman K, Nicoll-Griffith DA, Stresser DM, Ackermann JM, Turner SD, Miller VP, Crespi CL. The use of 3-[2-(N,N-diethyl-N-methylammonium)ethyl]-7-methoxy-4-methylcoumarin (AMMC) as a specific CYP2D6 probe in human liver microsomes. Drug Metab Dispos. 2001;29:1196–1200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman T, Ellis SW, Martin IJ, Lennard MS, Tucker GT. 1-Methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) is N-demethylated by cytochromes P450 2D6, 1A2 and 3A4–implications for susceptibility to Parkinson’s disease. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;277:685–690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cribb A, Nuss C, Wang R. Antipeptide antibodies against overlapping sequences differentially inhibit human CYP2D6. Drug Metab Dispos. 1995;23:671–675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Y, Newman B, Dunne MP, Silburn PA, Mellick GD. Further evidence that interactions between CYP2D6 and pesticide exposure increase risk for Parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:897. doi: 10.1002/ana.20143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Monte DA. The environment and Parkinson’s disease: is the nigrostriatal system preferentially targeted by neurotoxins? Lancet Neurol. 2003;2:531–538. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(03)00501-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutheil F, Dauchy S, Diry M, Sazdovitch V, Cloarec O, Mellottee L, Bieche I, Ingelman-Sundberg M, Flinois JP, de Waziers I, Beaune P, Decleves X, Duyckaerts C, Loriot MA. Xenobiotic-metabolizing enzymes and transporters in the normal human brain: regional and cellular mapping as a basis for putative roles in cerebral function. Drug Metab Dispos. 2009;37:1528–1538. doi: 10.1124/dmd.109.027011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards RJ, Price RJ, Watts PS, Renwick AB, Tredger JM, Boobis AR, Lake BG. Induction of cytochrome P450 enzymes in cultured precision-cut human liver slices. Drug Metab Dispos. 2003;31:282–288. doi: 10.1124/dmd.31.3.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbaz A, Levecque C, Clavel J, Vidal JS, Richard F, Amouyel P, Alperovitch A, Chartier-Harlin MC, Tzourio C. CYP2D6 polymorphism, pesticide exposure, and Parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:430–434. doi: 10.1002/ana.20051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong SP, Tsang KS, Chan AB, Lu G, Poon WS, Li K, Baum LW, Ng HK. Trophism of neural progenitor cells to embryonic stem cells: neural induction and transplantation in a mouse ischemic stroke model. J Neurosci Res. 2007;85:1851–1862. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonne-Pfister R, Bargetzi MJ, Meyer UA. MPTP, the neurotoxin inducing Parkinson’s disease, is a potent competitive inhibitor of human and rat cytochrome P450 isozymes (P450bufI, P450db1) catalyzing debrisoquine 4-hydroxylation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1987;148:1144–1150. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(87)80252-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilham DE, Cairns W, Paine MJ, Modi S, Poulsom R, Roberts GC, Wolf CR. Metabolism of MPTP by cytochrome P4502D6 and the demonstration of 2D6 mRNA in human foetal and adult brain by in situ hybridization. Xenobiotica. 1997;27:111–125. doi: 10.1080/004982597240802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto W, Ota T, Morikawa N, Otori Y, Hara H, Kawazu K, Miyawaki N, Tano Y. Protective effects of timolol against the neuronal damage induced by glutamate and ischemia in the rat retina. Brain Res. 2002;958:10–19. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03372-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han YS, Lee CS. Antidepressants reveal differential effect against 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium toxicity in differentiated PC12 cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;604:36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herraiz T, Guillen H, Aran VJ, Idle JR, Gonzalez FJ. Comparative aromatic hydroxylation and N-demethylation of MPTP neurotoxin and its analogs, N-methylated beta-carboline and isoquinoline alkaloids, by human cytochrome P450 2D6. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2006;216:387–398. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herraiz T, Guillen H, Galisteo J. N-methyltetrahydro-beta-carboline analogs of 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) neurotoxin are oxidized to neurotoxic beta-carbolinium cations by heme peroxidases. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;356:118–123. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.02.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiroi T, Imaoka S, Funae Y. Dopamine formation from tyramine by CYP2D6. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;249:838–843. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgson E. In vitro human phase I metabolism of xenobiotics I: pesticides and related chemicals used in agriculture and public health, September 2001. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2001;15:296–299. doi: 10.1002/jbt.10011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez-Jimenez FJ, Tabernero C, Mena MA, Garcia de Yebenes J, Garcia de Yebenes MJ, Casarejos MJ, Pardo B, Garcia-Agundez JA, Benitez J, Martinez A, Garcia-Asenio JAL. Acute effects of 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine in a model of rat designated a poor metabolizer of debrisoquine. J Neurochem. 1991;57:81–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1991.tb02102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolivalt C, Minn A, Vincent-Viry M, Galteau MM, Siest G. Dextromethorphan O-demethylase activity in rat brain microsomes. Neurosci Lett. 1995;187:65–68. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)11339-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang DH, Rettie AE, Bocker RH. Identification of enzymes involved in the metabolism of atrazine, terbuthylazine, ametryne, and terbutryne in human liver microsomes. Chem Res Toxicol. 1997;10:1037–1044. doi: 10.1021/tx970081l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liou HH, Hsu HJ, Tsai YF, Shih CY, Chang YC, Lin CJ. Interaction between nicotine and MPTP/MPP+ in rat brain endothelial cells. Life Sci. 2007;81:664–672. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann A, Miksys S, Lee A, Mash DC, Tyndale RF. Induction of the drug metabolizing enzyme CYP2D in monkey brain by chronic nicotine treatment. Neuropharmacology. 2008;55:1147–1155. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matoh N, Tanaka S, Takehashi M, Banasik M, Stedeford T, Masliah E, Suzuki S, Nishimura Y, Ueda K. Overexpression of CYP2D6 attenuates the toxicity of MPP+ in actively dividing and differentiated PC12 cells. Gene Expr. 2003;11:117–124. doi: 10.3727/000000003108749017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCann SJ, Pond SM, James KM, Le Couteur DG. The association between polymorphisms in the cytochrome P-450 2D6 gene and Parkinson’s disease: a case-control study and meta-analysis. J Neurol Sci. 1997;153:50–53. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(97)00179-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillan CR, Sharma R, Ottenhof T, Niles LP. Modulation of tyrosine hydroxylase expression by melatonin in human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells. Neurosci Lett. 2007;419:202–206. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miksys S, Rao Y, Sellers EM, Kwan M, Mendis D, Tyndale RF. Regional and cellular distribution of CYP2D subfamily members in rat brain. Xenobiotica. 2000;30:547–564. doi: 10.1080/004982500406390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miksys S, Rao Y, Hoffmann E, Mash DC, Tyndale RF. Regional and cellular expression of CYP2D6 in human brain: higher levels in alcoholics. J Neurochem. 2002;82:1376–1387. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modi S, Gilham DE, Sutcliffe MJ, Lian LY, Primrose WU, Wolf CR, Roberts GC. 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine as a substrate of cytochrome P450 2D6: allosteric effects of NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase. Biochemistry. 1997;36:4461–4470. doi: 10.1021/bi962633p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicotra A, Parvez SH. Cell death induced by MPTP, a substrate for monoamine oxidase B. Toxicology. 2000;153:157–166. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(00)00311-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen TL, Rasmussen BB, Flinois JP, Beaune P, Brosen K. In vitro metabolism of quinidine: the (3S)-3-hydroxylation of quinidine is a specific marker reaction for cytochrome P-4503A4 activity in human liver microsomes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;289:31–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olanow CW. The pathogenesis of cell death in Parkinson’s disease –2007. Mov Disord. 2007;22:S335–S342. doi: 10.1002/mds.21675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill MJ, Murray TK, Lakics V, Visanji NP, Duty S. The role of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in acute and chronic neurodegeneration. Curr Drug Targets CNS Neurol Disord. 2002;1:399–411. doi: 10.2174/1568007023339166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poeaknapo C, Schmidt J, Brandsch M, Drager B, Zenk MH. Endogenous formation of morphine in human cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:14091–14096. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405430101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presgraves SP, Ahmed T, Borwege S, Joyce JN. Terminally differentiated SH-SY5Y cells provide a model system for studying neuroprotective effects of dopamine agonists. Neurotox Res. 2004;5:579–598. doi: 10.1007/BF03033178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quik M, Parameswaran N, McCallum SE, Bordia T, Bao S, McCormack A, Kim A, Tyndale RF, Langston JW, Di Monte DA. Chronic oral nicotine treatment protects against striatal degeneration in MPTP-treated primates. J Neurochem. 2006;98:1866–1875. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sams C, Mason HJ, Rawbone R. Evidence for the activation of organophosphate pesticides by cytochromes P450 3A4 and 2D6 in human liver microsomes. Toxicol Lett. 2000;116:217–221. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4274(00)00221-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S, Singh K, Patel DK, Singh C, Nath C, Singh VK, Singh RK, Singh MP. The expression of CYP2D22, an ortholog of human CYP2D6, in mouse striatum and its modulation in 1-methyl 4-phenyl- 1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine-induced Parkinson’s disease phenotype and nicotine-mediated neuroprotection. Rejuvenation Res. 2009;12:185–197. doi: 10.1089/rej.2009.0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staal RG, Yang JM, Hait WN, Sonsalla PK. Interactions of 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium and other compounds with P-glycoprotein: relevance to toxicity of 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine. Brain Res. 2001;910:116–125. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02674-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strobel HW, Kawashima H, Geng J, Sequeira D, Bergh A, Hodgson AV, Wang H, Shen S. Expression of multiple forms of brain cytochrome P450. Toxicol Lett. 1995;82–83:639–643. doi: 10.1016/0378-4274(95)03509-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T, Fujita S, Narimatsu S, Masubuchi Y, Tachibana M, Ohta S, Hirobe M. Cytochrome P450 isozymes catalyzing 4-hydroxylation of parkinsonism-related compound 1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline in rat liver microsomes. FASEB J. 1992;6:771–776. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.6.2.1537468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang J, Cao Y, Rose RL, Hodgson E. In vitro metabolism of carbaryl by human cytochrome P450 and its inhibition by chlorpyrifos. Chem Biol Interact. 2002;141:229–241. doi: 10.1016/s0009-2797(02)00074-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyndale RF, Li Y, Li NY, Messina E, Miksys S, Sellers EM. Characterization of cytochrome P-450 2D1 activity in rat brain: high-affinity kinetics for dextromethorphan. Drug Metab Dispos. 1999;27:924–930. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaglini F, Pardini C, Viaggi C, Bartoli C, Dinucci D, Corsini GU. Involvement of cytochrome P450 2E1 in the 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine-induced mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. J Neurochem. 2004;91:285–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voirol P, Jonzier-Perey M, Porchet F, Reymond MJ, Janzer RC, Bouras C, Strobel HW, Kosel M, Eap CB, Baumann P. Cytochrome P-450 activities in human and rat brain microsomes. Brain Res. 2000;855:235–243. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02354-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts PM, Riedl AG, Douek DC, Edwards RJ, Boobis AR, Jenner P, Marsden CD. Co-localization of P450 enzymes in the rat substantia nigra with tyrosine hydroxylase. Neuroscience. 1998;86:511–519. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00649-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood JP, Schmidt KG, Melena J, Chidlow G, Allmeier H, Osborne NN. The beta-adrenoceptor antagonists metipranolol and timolol are retinal neuroprotectants: comparison with betaxolol. Exp Eye Res. 2003;76:505–516. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(02)00335-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto T, Suzuki A, Kohno Y. High-throughput screening to estimate single or multiple enzymes involved in drug metabolism: microtitre plate assay using a combination of recombinant CYP2D6 and human liver microsomes. Xenobiotica. 2003;33:823–839. doi: 10.1080/0049825031000140887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao H, Costache AD, Sem DS. Chemical proteomic tool for ligand mapping of CYP antitargets: an NMR-compatible 3D QSAR descriptor in the Heme-Based Coordinate System. J Chem Inf Comput Sci. 2004;44:1456–1465. doi: 10.1021/ci034208q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu AM, Idle JR, Krausz KW, Kupfer A, Gonzalez FJ. Contribution of individual cytochrome P450 isozymes to the O-demethylation of the psychotropic beta-carboline alkaloids harmaline and harmine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;305:315–322. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.047050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue J, Miksys S, Hoffmann E, Tyndale RF. Chronic nicotine treatment induces rat CYP2D in the brain but not in the liver: an investigation of induction and time course. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2008;33:54–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]