Abstract

Cysteinate oxygenation is intimately tied to the function of both cysteine dioxygenases (CDOs) and nitrile hydratases (NHases), and yet the mechanisms by which sulfurs are oxidized by these enzymes are unknown, in part because intermediates have yet to be observed. Herein, we report a five-coordinate bis-thiolate ligated Fe(III) complex, [FeIII(S2Me2N3-(Pr,Pr))]+ (2), that reacts with oxo atom donors (PhIO, IBX-ester, and H2O2) to afford a rare example of a singly oxygenated sulfenate, [FeIII(η2-SMe2O)(SMe2)N3(Pr,Pr)]+ (5), resembling both a proposed intermediate in the CDO catalytic cycle and the essential NHase Fe-S(O)Cys114 proposed to be intimately involved in nitrile hydrolysis. Comparison of the reactivity of 2 with that of a more electron-rich, crystallographically characterized derivative, [FeIIIS2Me2NMeN2amide(Pr,Pr)]− (8), shows that oxo atom donor reactivity correlates with the metal ion’s ability to bind exogenous ligands. Density functional theory calculations suggest that the mechanism of S-oxygenation does not proceed via direct attack at the thiolate sulfurs; the average spin-density on the thiolate sulfurs is approximately the same for 2 and 8, and Mulliken charges on the sulfurs of 8 are roughly twice those of 2, implying that 8 should be more susceptible to sulfur oxidation. Carboxamide-ligated 8 is shown to be unreactive towards oxo atom donors, in contrast to imine-ligated 2. Azide (N3−) is shown to inhibit sulfur oxidation with 2, and a green intermediate is observed, which then slowly converts to sulfenate-ligated 5. This suggests that the mechanism of sulfur oxidation involves initial coordination of the oxo atom donor to the metal ion. Whether the green intermediate is an oxo atom donor adduct, Fe-O═I-Ph, or an Fe(V)═O remains to be determined.

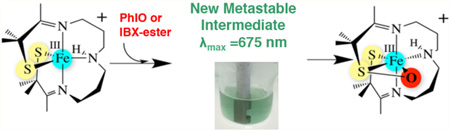

Graphical abstract

INTRODUCTION

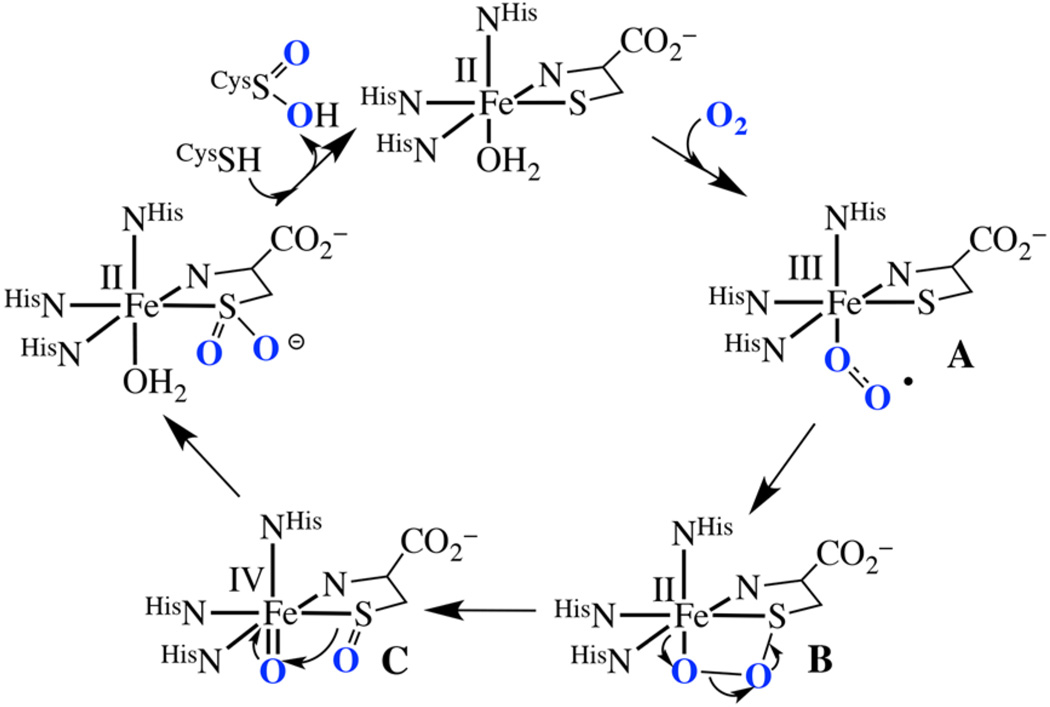

Cysteine dioxygenases (CDOs) are non-heme Fe-enzymes that catalyze the O2-promoted oxygenation of cysteinate (cysS−) to cysteine sulfinic acid (cysSO2−).1–8 A singly oxygenated cysteine sulfenate (cysSO−) is proposed to be involved as an intermediate. High levels of cysteine can cause rheumatoid arthritis, and neurological disorders such as Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease.5, 9 Thus, having a mechanism for its degradation is important to human health. The CDO enzyme has also been shown to suppress tumor growth by combatting the tumor’s defense against reactive oxygen species.10 An epigenetic event can turn off CDO tumor suppression,11 however, via methylation of the gene responsible for the biosynthesis of CDO. Methylated CDO genes are found in ∼60% of breast cancers and correlate with the progression of the disease and outcome.12 The CDO mechanism (Figure 1) is proposed to involve cysteine binding to the metal ion, followed by O2 binding, cis to the cysS−, to afford an FeIII-O2•−intermediate (A). The superoxo radical is then proposed to couple with the FeII-cysS•↔ FeIII-cysS− sulfur to afford a fourmembered-ring structure, RS-FeII-O-O (B).5 This step is unprecedented, in part because there are very few reported FeIII-O2•−,8, 13, 14 but more importantly, because none have RS−ligands in the coordination sphere. Upon heterolytic cleavage of the O-O bond, a high-valent iron−oxo intermediate with a singly oxygenated sulfenate, (RSO)FeIV═O (C), is proposed to form, which undergoes cis-migration to afford the final doubly oxygenated cysteine sulfinate.1, 5 Although theoretical calculations have indicated that the direct involvement of the metal ion of CDO provides a lower energy pathway to sulfur oxygenation,1, 5 this has not been experimentally proven. Intermediates A–C (Figure 1) have yet to be observed. The lack of spectroscopic data for any of the proposed CDO intermediates has made it impossible to calibrate theoretical calculations.5

Figure 1.

Proposed mechanism of CDO catalyzed cysteine oxygenation.

Dioxygen has been shown to react with small-molecule iron thiolate (RS−) complexes to afford doubly or triply oxygenated thiolates.15–20 For example, cysteinate-ligated TpFeIIScys reacts with O2 to afford cysSO2− (the product of CDO5); however, no intermediates were observed.21 Iron complexes containing a non-tethered, monodentate RS ligand trans to the O2 binding site have been shown to react with O2 to afford an FeIV═O + RSSR, 3, 22 in contrast to cis-thiolate-ligated complexes, which have been shown to react with O2 to afford doubly (RSO2-Fe) or triply (RSO3-Fe) oxygenated derivatives.1–4, 22, 23 Singly oxygenated RSO-Fe sulfenate intermediates are not observed in these cases. Whether these reactions are metal-mediated, or involve direct attack of O2 at sulfur, has not been determined, although the orientation dependence would suggest the former. The mechanism of O2-induced oxygenation of Ni-thiolate complexes, on the other hand, has been shown to involve direct attack by O2 at the thiolate sulfurs.24

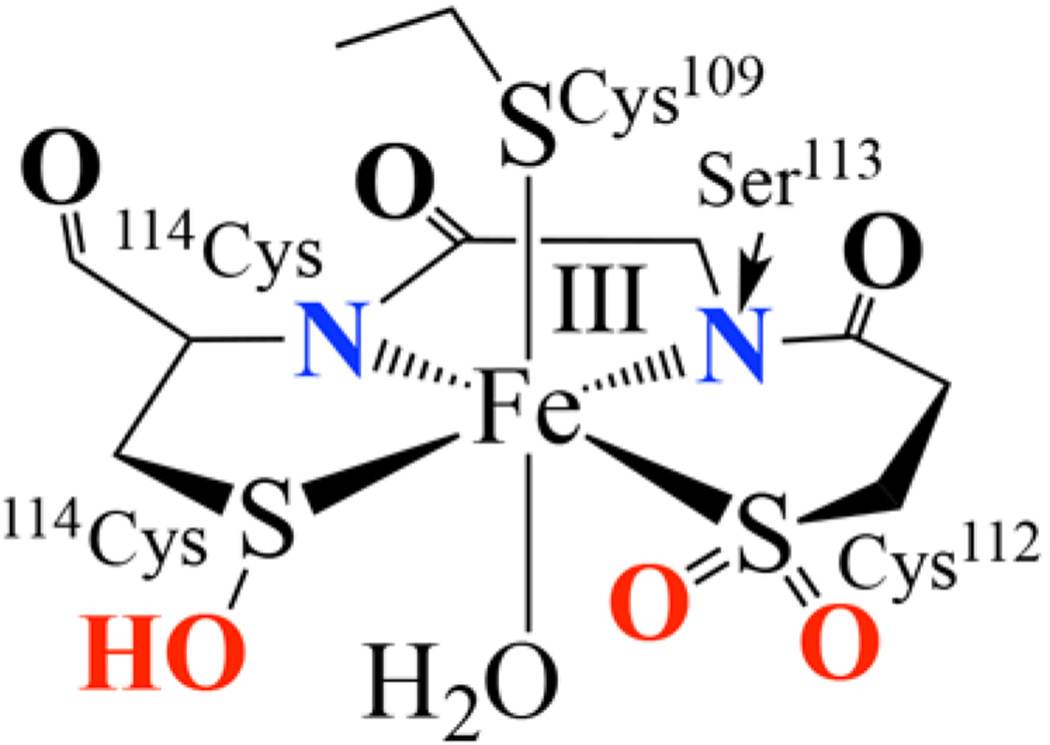

Oxygenated cysteinates have been shown to play a growing number of diverse roles in cellular processes, including T-cell activation, redox signaling in mammalian cells,25 signal transduction, oxygen metabolism, oxidative stress response, and transcriptional regulation.25, 26 They are also required for enzyme activity in some cases (e.g, nitrile hydratase (NHase),27–31 NADH peroxidase,32 and peroxiredoxins33). Nitrile hydratases are a class of thiolate-ligated non-heme iron enzymes for which cysteinate oxygenation is intimately tied to function. These enzymes, which catalyze the enantioselective hydrolysis of nitriles to amides,34–38 contain an Fe(III) (or Co(III)) active site ligated by three cysteinates, two of which are post-translationally modified (Scheme 1), one to a sulfenic acid (114Cys-S-OH) 31, 39, 40 and the other to a sulfinate (112Cys-SO2−).41 Sulfur K-edge X-ray absorption spectroscopic studies have shown that the NHase sulfenic acid residue is protonated,39 whereas the sulfinate (RSO2−) remains unprotonated.39 The enzyme becomes inactive when a second oxygen atom is added to the sulfenic acid,114Cys-S-OH, implying that it plays a specific role in catalysis.42 This is supported by time-resolved crystallography43 and crystallographic characterization of 114Cys-S-bound inhibitors.31 Coupled with theoretical calculations,27 these experimental data provide evidence that the sulfenate oxygen is intimately involved in the NHase mechanism. The mechanism by which post-translationally modified NHase sulfenate and sulfinate oxygens are inserted has been proposed to involve O2-induced formation of a thiolate-ligated high-valent oxo intermediate.22, 29 There are no experimental data available to verify this possibility, however.

Scheme 1.

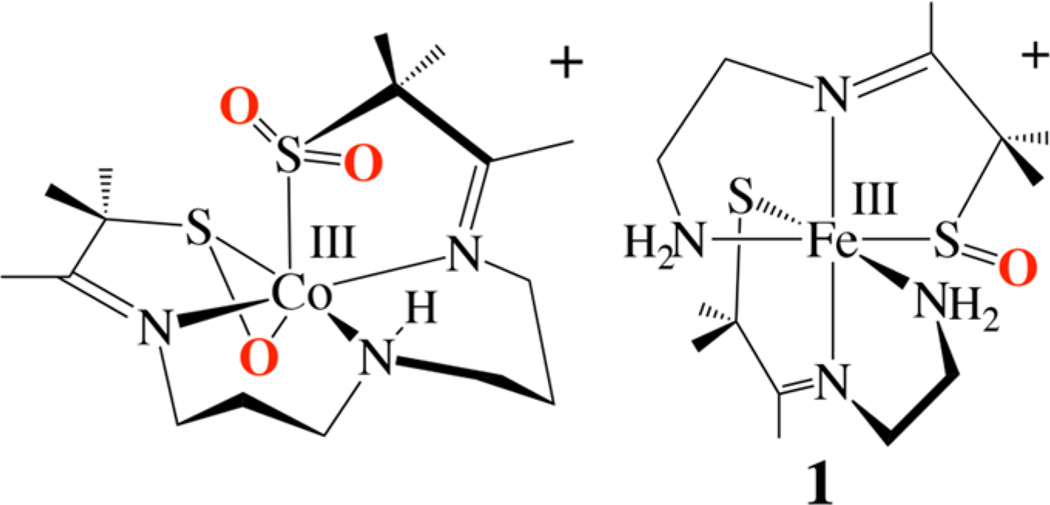

Singly oxygenated sulfenates are difficult to trap,26, 44–47 even when they are coordinated to a metal ion (i.e., M-S(R)-O−). 24, 48, 49 There are significantly more examples of doubly oxygenated metal-sulfinate (RSO2−) complexes. 15–20 Examples of singly oxygenated RS═O or RS-OH compounds include [CoIII(η2-SO)(SO2)N3(Pr,Pr)]+ (Scheme 2),49 [FeIII(ADIT)-(ADIT-O)]+ (1),48 and [FeIII(ADIT)(ADIT-OH)] 2+.48

Scheme 2.

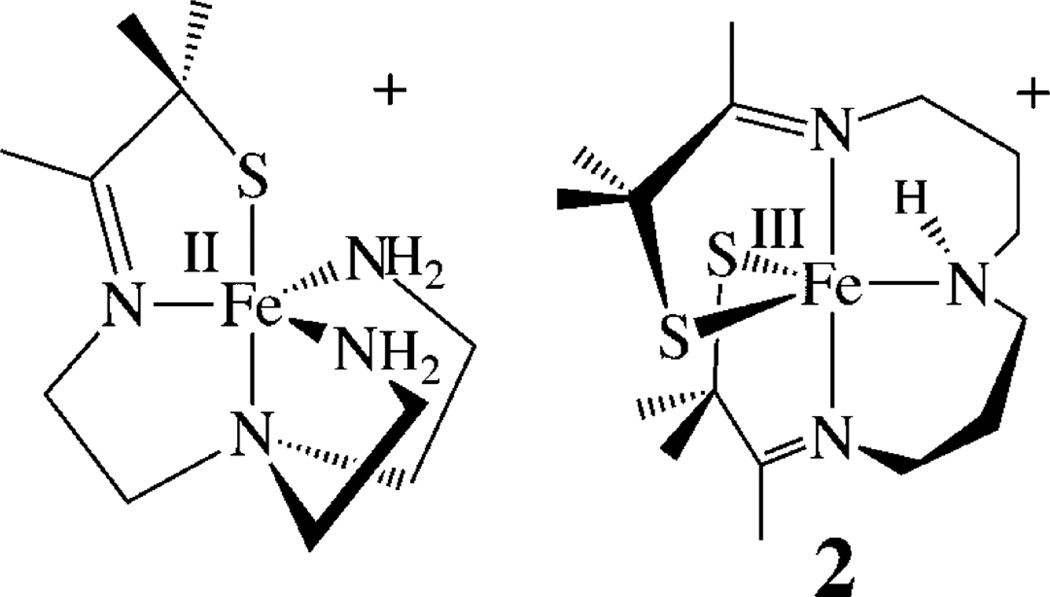

In order to understand how thiolates promote O2 activation50–52 and tune the electronic, magnetic, and reactivity properties of peroxo, oxo, and hydroxo intermediates, we have been exploring the reactivity of coordinatively unsaturated thiolate-ligated Fe (and Mn) complexes with dioxygen and its reduced derivatives.51, 53–59 Although an open coordination site is required for O2 binding, thiolates are known to intercept open coordination sites by forming intermolecular M-SR-M bridges, resulting in oligomerization. Despite this, we,17, 51, 54, 59–67 and others,2, 3, 16, 18, 68–70 have synthesized a variety of coordinatively unsaturated mononuclear thiolate-ligated iron complexes that are capable of binding small molecules. For example, thiolate-ligated [FeII(N4SMe2-(tren))]+,54, 71 and bis-thiolate-ligated [FeIII(S2Me2N3(Pr,Pr))] (2,63 Scheme 3), are five-coordinate, and contain flexible ligands capable of accommodating a sixth ligand,62, 63, 72 as well as a variety of metal ions, in multiple oxidation states.59, 60, 62, 63, 72–74 Both ligands constrain the geometry so that added “substrates” are forced to bind cis to a thiolate (e.g., structures 3 and 4, Scheme 4).64, 65, 75, 76 For example, superoxide (O2−) reacts with reduced [FeII(N4SMe2(tren))] + at low temperatures in the presence of a proton donor59, 75, 77 to afford a metastable, low-spin (S = 1/2; g┴ = 2.14; g║ = 1.97) hydroperoxo intermediate, [FeIII(N4SMe2(tren))(OOH)]+ (3, Scheme 4; υO-O = 784 cm−1).54 Bis-thiolate ligated 2 (Scheme 3) was shown to bind L = N3− (4) and NO cis to one of the thiolates and trans to the other (Scheme 4).63, 78 Despite the π-donor properties of RS− ligands, the highly covalent Fe−S bonds of oxidized [FeIII(N4SMe2(tren))L]+ (L = MeCN, HOO−(3)),54, 64, 65 [FeIII(S2Me2N3(Pr,Pr))]+ (2), and [FeIII(S2Me2N3-(Pr,Pr))(N3)] (4)63 were all shown to favor a low-spin state (S = 1/2), due to the nephalauxetic effect.79 The trans-thiolate of 4 was shown to labilize the azide63, thereby promoting reversible L-binding.80 Herein we examine the reactivity of bis-thiolate-ligated [FeIII(S2Me2N3(Pr,Pr))] + (2, Scheme 3) with oxo atom donors in order to determine how the presence of both a cis-and trans-thiolate influences electronic structure and reactivity.

Scheme 3.

Scheme 4.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

General Methods

All reactions were performed under an atmosphere of dinitrogen in a glovebox, using standard Schlenk techniques, or using a custom-made solution cell equipped with a threaded glass connector sized to fit a dip probe. Reagents purchased from commercial vendors were of the highest purity available and used without further purification. Toluene, tetrahydrofuran (THF), diethyl ether (Et2O), and acetonitrile (MeCN) were rigorously degassed and purified using solvent purification columns housed in a custom stainless steel cabinet, dispensed via a stainless steel Schlenk-line (GlassContour). Methanol (MeOH) and ethanol (EtOH) were distilled from magnesium methoxide or ethoxide and degassed prior to use. Methylene chloride (DCM) was distilled from CaH2 and degassed prior to use. 1H NMR spectra were recorded on Bruker AV 300 or Bruker AV 301 FT-NMR spectrometers and are referenced to an external standard of tetramethylsilane (paramagnetic compounds) or to residual protio-solvent (diamagnetic compounds). Chemical shifts are reported in ppm, and coupling constants (J) are in Hz. EPR spectra were recorded on a Bruker EMX CW-EPR spectrometer operating at X-band frequency at 7 K. IR spectra were recorded on a PerkinElmer 1700 FT-IR spectrometer as KBr pellets. Cyclic voltammograms were recorded in MeCN (100 mM Bun4N(PF6) solutions) on a PAR 273 potentiostat utilizing a glassy carbon working electrode, platinum auxiliary electrode, and a saturated calomel electrode (SCE) reference electrode. Magnetic moments (solution state) were obtained using Evans’s method as modified for super-conducting solenoids.81, 82 Temperatures were obtained using Van Geet’s method.83 Solid-state magnetic measurements were obtained with polycrystalline samples in gel-caps using a Quantum Design MPMS S5 SQUID magnetometer. Ambient-temperature electronic absorption spectra were recorded on a Hewlett-Packard model 8450 spectrometer, interfaced to an IBM personal computer. Low-temperature electronic absorption spectra were recorded using a Varian Cary 50 spectrophotometer equipped with a fiber optic cable connected to a “dip” attenuated total reflection probe (C-technologies), with a custom-built two-neck solution sample holder equipped with a threaded glass connector (sized to fit the dip probe). Elemental analyses were performed by Galbraith Labs, Knoxville, TN, and Atlantic Microlabs, Norcross, GA. Thiolate-ligated [FeIII(S2Me2N3-(Pr,Pr))](PF6) (2) was synthesized as previously described.63

Synthesis of [FeIII(η2-SMe2O)(SMe2N3(Pr,Pr)](PF6) (5) via the Addition of PhIO to 2

To a stirred solution of [FeIII(S2Me2N3-(Pr,Pr))](PF6) (2) (275 mg, 0.52 mmol) in MeOH (20 mL) at −35 °C was added dropwise a 2 mL MeOH solution containing 1.2 equiv of iodosobenzene (PhIO) (137 mg, 0.62 mmol). The solution was allowed to stir for 1 h at −35 °C, and then stored in the freezer overnight. After filtration, the volume was reduced to 3 mL, layered with 25 mL of Et2O, and cooled to −35 °C overnight to afford 5 (153 mg, 0.28 mmol, 54%) as a pink crystalline solid. Electronic absorption (CH3CN): λmax (ε, M−1 cm−1) = 333 (4410), 510 (1540) nm; (MeOH): λmax (ε, M−1 cm−1) = 325 (4870), 510 (1700), 760 (248) nm (Figure S-1). IR (KBr pellet) ν (cm−1): 1625 (C═N); 1024 (S-O). Reduction potential (MeCN): Ep,c = −0.960 V (irrev.) vs SCE. Solution magnetic moment (310.2 K; MeOH): µeff = 1.99 µB. EPR (DCM/toluene glass (1:1), 7 K): g1 = 2.17, g2 = 2.11, g3 = 1.98. ESI-MS calcd for [FeC16N3S2H31O]+: 401.3; found: 401.2. Anal. Calcd for FeC16H31N3OS2PF6: C, 35.2; H, 5.7; N, 7.7. Found: C, 35.39; H, 5.57; N, 7.77.

Formation of [FeIII(η2-SMe2O)(SMe2N3(Pr,Pr)](PF6) (5) via the Addition of Hydrogen Peroxide to 2

Oxidized 2 (5 mg, 0.01 mmol) was dissolved in 20 mL of MeOH and placed in a sealed UV–vis dip-probe cell under a N2 atmosphere. To this was added 1.0 equiv of H2O2 (1 µL of a 30% aqueous solution, 0.01 mmol) at room temperature via syringe to afford a pink air-stable compound (λmax= 510 nm (1540 M−1 cm−1); ESI-MS (M+1): 401). Complex 5 is stable both at room temperature and in air.

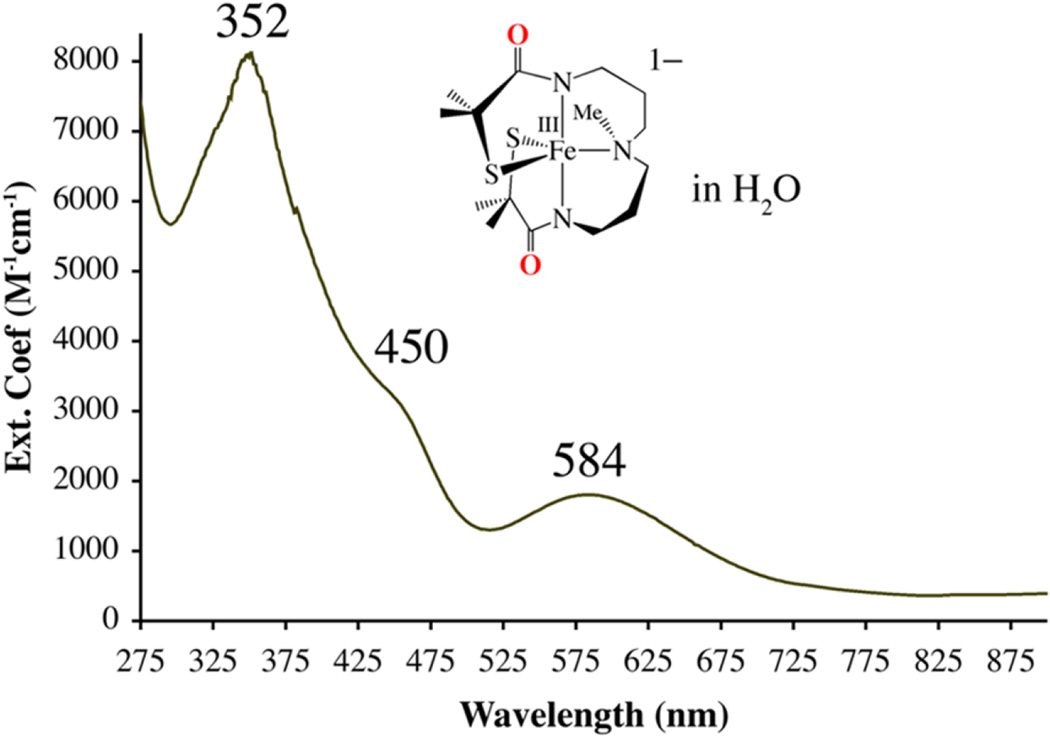

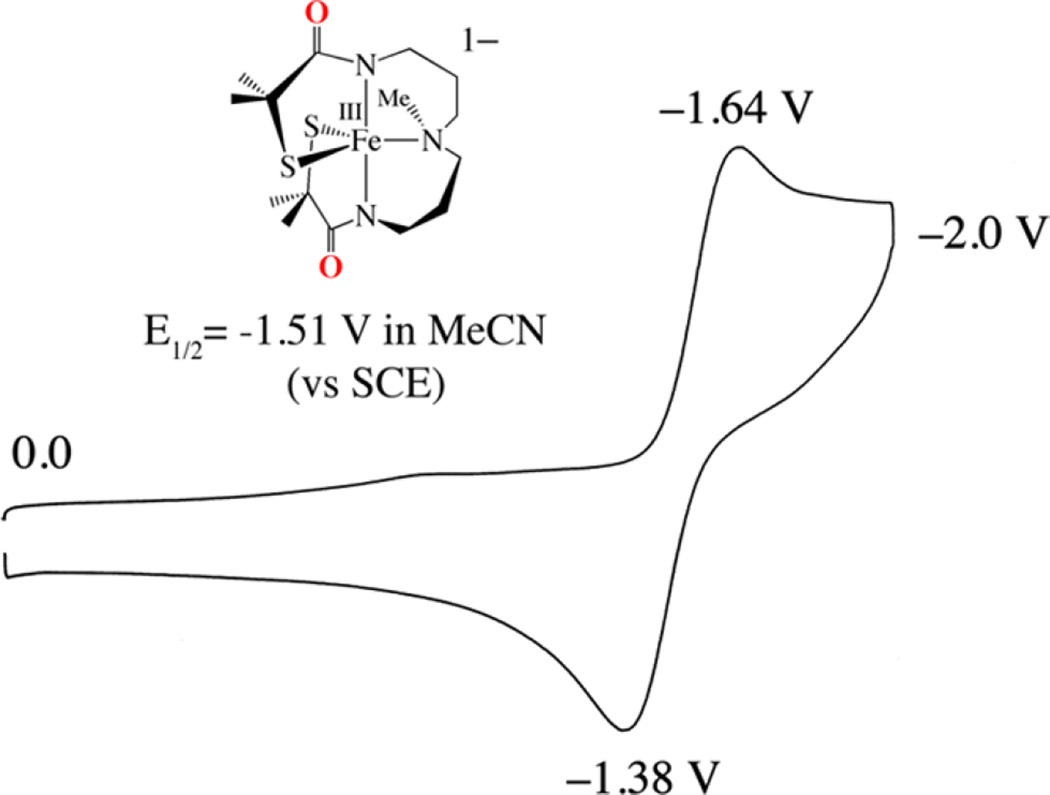

Synthesis of (Et4N)[FeIIIS2Me2NMeN2amide(Pr,Pr)] (8)

To a stirred solution of (HSMe)2(NMe)(HNamide)2(Pr,Pr)·HCl (C, see Supporting Information for synthesis) (100 mg, 0.26 mmol) in MeOH (5 mL) at −35 °C was added dropwise a pre-cooled (−35 °C) solution of (Et4N)[FeCl4] (85 mg, 0.26 mmol) in MeOH (3 mL). A pre-cooled (−35 °C) solution of NaOMe (70 mg, 1.3 mmol) in MeOH (5 mL) was then added, and the resulting reaction mixture was allowed to stir overnight at ambient temperature. The intense olive green solution was filtered and concentrated to dryness. The solid was re-dissolved in MeCN and filtered. The filtrate was concentrated to a minimum amount of MeCN (∼2 mL), layered with 10 mL of Et2O, and cooled to −35 °C overnight to afford 8 (110 mg, 0.21 mmol, 80%) as a dark green crystalline solid. Electronic absorption (CH3CN): λmax (ε, M−1 cm−1) = 352 (8210), 428 (3590), 581 (1280) nm; (MeOH): λmax (ε, M−1 cm−1) = 348 (8150), 588 (1210) nm; (H2O): λmax (ε, M−1 cm−1) = 352 (8060), 584 (1530) nm. IR (KBr pellet) ν (cm−1): 1564 (C═O). E1/2 (MeCN) = −1.51 V vs SCE. Solution magnetic moment (298 K; MeOH): µeff = 3.75 µB. EPR (MeOH/EtOH glass (9:1), 9 K): g1 = 4.72, g2 = 2.82, g3 = 1.92. ESI-MS calcd for [FeC13H21N2O2S3]−: 389.4, found: 389.3. Anal. Calcd for FeC23H47N4O2S2: C, 52.0; H, 8.9; N, 10.5. Found: C, 52.3; H, 8.87; N, 10.49.

Formation of a Green Intermediate via the Addition of IBX-Ester to 2

A 0.238 mM solution of 2 was prepared in 5 mL of MeOH under an inert atmosphere in a drybox. The resulting solution was transferred via gastight syringe to a custom-made two-neck vial equipped with a septum cap and threaded dip-probe feed-through adaptor that had previously been purged with argon and contained a stir bar. This solution was cooled in an acetone/dry ice bath to −73 °C. To this was added 10 equiv of IBX-ester (isopropyl 2-iodoxybenzoate) (50 µL of 238 mM solution of IBX-ester in MeOH), resulting in the formation of a metastable green intermediate (λmax = 675 nm).

Formation of a Green Intermediate via the Addition of PhIO to 2

A 0.238 mM solution of 2 was prepared in 5 mL of MeOH or THF under an inert atmosphere in a drybox. The resulting solution was transferred via gastight syringe to a custom-made two-neck vial equipped with a septum cap and threaded dip-probe feed-through adaptor that had previously been purged with argon and contained a stir bar. This solution was cooled in an acetone/dry ice bath to −73 °C. To this was added 1–4 equiv of PhIO (50–200 µL of 23.8 mM solution in MeOH), resulting in the formation of a metastable intermediate (λmax = 675 nm).

DFT Calculations

All geometry optimizations were performed utilizing the ORCA v.3.0 quantum chemistry package84 and originated from X-ray crystallographic coordinates. The BP86 functional,85, 86 with the resolution of identity approximation (RI),87 dispersion correction (D3BJ),88 and zeroth-order regular approximation for relativistic effects (ZORA),89 was employed, using a dense integration grid (Grid4), def2-TZVP basis set,90 and def2-TZVP/J auxiliary basis set.87 In addition, the conductor-like screening model (COSMO), using acetonitrile (ε = 37.5) as the solvent,91 was employed. All optimized geometries were visualized using Avogadro.

X-ray Crystallographic Structure Determination

A red crystal plate, 0.24 × 0.24 × 0.05 mm, of 5 was mounted on a glass capillary with oil. Data were collected at −143 °C. The crystal-to-detector distance was set to 30 mm, and exposure time was 30 s per degree for all data sets, with a scan width of 1.4°. The data collection was 89.1% complete to 28.34° and 96.1% complete to 25° in θ. A total of 63 733 partial and complete reflections were collected, covering the indices h = −16 to 16, k = −18 to 20, l = −19 to 19. A total of 5215 reflections were symmetry independent, and the Rint = 0.0698 indicated that the data were of average quality (0.07). Indexing and unit cell refinements indicated a monoclinic P lattice in the space group P21/c (No. 14).

A black crystal prism, 0.48 × 0.44 × 0.36 mm, of 8 was mounted on a glass capillary with oil. Data were collected at −143 °C. The crystal-to-detector distance was set to 40 mm, and exposure time was 20 s per degree for all sets, with a scan width of 1.5°. The data collection was 94.5% complete to 28.63° and 99.8% complete to 25° in θ. A total of 41 494 partial and complete reflections were collected, covering the indices h = −23 to 23, k = −11 to 11, l = −23 to 23. A total of 6353 reflections were symmetry independent, and the Rint = 0.063 indicated that the data were of average quality (0.07). Indexing and unit cell refinement indicated an orthorhombic P lattice in the space group Pna21 (No. 33).

The data for both 5 and 8 were integrated and scaled using Denzohkl-SCALEPACK, and an absorption correction was performed using SORTAV. Scattering factors were obtained from Waasmair and Kirfel.92 Solution by direct methods (SIR97) produced a complete heavy-atom phasing model consistent with the proposed structures. All non-hydrogen atoms were refined anisotropically by full-matrix least-squares methods, and all hydrogen atoms were then located using a riding model. Crystal data for 5 and 8 are presented in Table 1; CIF files for 5 and 8 are available as Supporting Information. Selected bond distances and angles are assembled in Table 2 in the following section.

Table 1.

Crystal Data for [FeIII(η2-SMe2O)(SMe2N3(Pr,Pr)](PF6) (5) and (Et4N)[FeIIIS2Me2NMeN2amide(Pr,Pr)] (8)

| 5 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|

| formula | C16H31F6FeN3OPS2 | C23H47FeN4O2S2 |

| MW (g/mol) | 546.38 | 531.62 |

| temp (K) | 130(2) | 130(2) |

| unit cella | monoclinic | orthorhombic |

| space group | P21/c | Pna21 |

| a (Å) | 12.3550(5) | 17.9580(3) |

| b (Å) | 15.3070(8) | 8.5610(6) |

| c (Å) | 14.8020(7) | 18.1560(7) |

| α (deg) | 90 | 90 |

| β (deg) | 123.147(3) | 90 |

| γ (deg) | 90 | 90 |

| V (Å3) | 2343.79(19) | 2791.3(2) |

| Z | 4 | 4 |

| σcalc (mg/m3) | 1.548 | 1.265 |

| Rb | 0.0721 | 0.0477 |

| Rw | 0.2040 | 0.1219 |

| GOF | 1.001 | 0.940 |

In all cases: Mo Kα (λ = 0.71070 Å) radiation.

R = ∑||Fo| – |Fc||/∑| Fo|; Rw = [∑w(|Fo| – |Fc|)2/∑wFo2]1/2, where w−1 = [σ2count + (0.05F2)]/4F2.

Table 2.

Comparison of Selected Bond Distances (Å) and Angles (deg) for Imine-Ligated [FeIII(S2Me2N3(Pr,Pr))]+ (2),63 Its Singly Oxygenated Derivative [FeIII(η2-SMe2O)(SMe2N3(Pr,Pr)]+ (5), and Carboxamide-Ligated [FeIIIS2Me2NMeN2amide(Pr,Pr)]− (8)

| 2 | 5 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fe–S(1) | 2.133(2) | 2.142(2) | 2.231(1) |

| Fe–S(2) | 2.161(2) | 2.148(2) | 2.210(1) |

| Fe–N(1) | 1.967(4) | 1.976(4) | 1.934(3) |

| Fe–N(2) | 2.049(4) | 2.044(5) | 2.212(3) |

| Fe–N(3) | 1.954(4) | 1.954(4) | 1.924(3) |

| Fe–O(1) | N/A | 2.115(4) | N/A |

| S(1)–O(1) | N/A | 1.447(6) | N/A |

| N(1)–Fe–N(3) | 178.1(2) | 178.0(2) | 177.8(1) |

| S(1)–Fe–S(2) | 121.0(1) | 112.62(8) | 144.40(5 |

| S(1)–Fe–N(2) | 132.3(1) | 134.1(1) | 107.14(9 |

| S(2)–Fe–N(2) | 106.5(1) | 113.2(2) | 108.43(9 |

| S(1)–Fe–N(1) | 86.7(1) | 86.1(1) | 85.37(9) |

| S(2)–Fe–N(1) | 95.2(1) | 91.9(1) | 93.8(1) |

| S(1)–Fe–O(1) | N/A | 39.7(2) | N/Aa |

| O(1)–Fe–S(2) | N/A | 152.3(2) | N/Aa |

| O(1)–Fe–N(1) | N/A | 87.6(2) | N/Aa |

| O(1)–Fe–N(2) | N/A | 94.3(2) | N/Aa |

| O(1)–Fe–N(3) | N/A | 94.4(2) | N/Aa |

| τ | 0.76 | N/A | 0.56 |

In this structure, the only oxygens are associated with the carboxamide, and are not coordinated to the metal.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

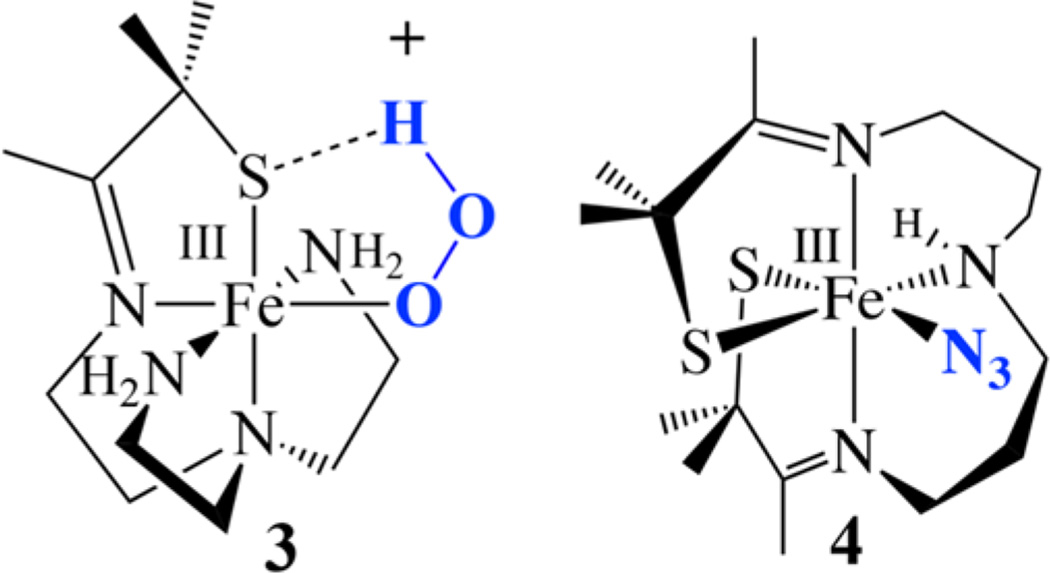

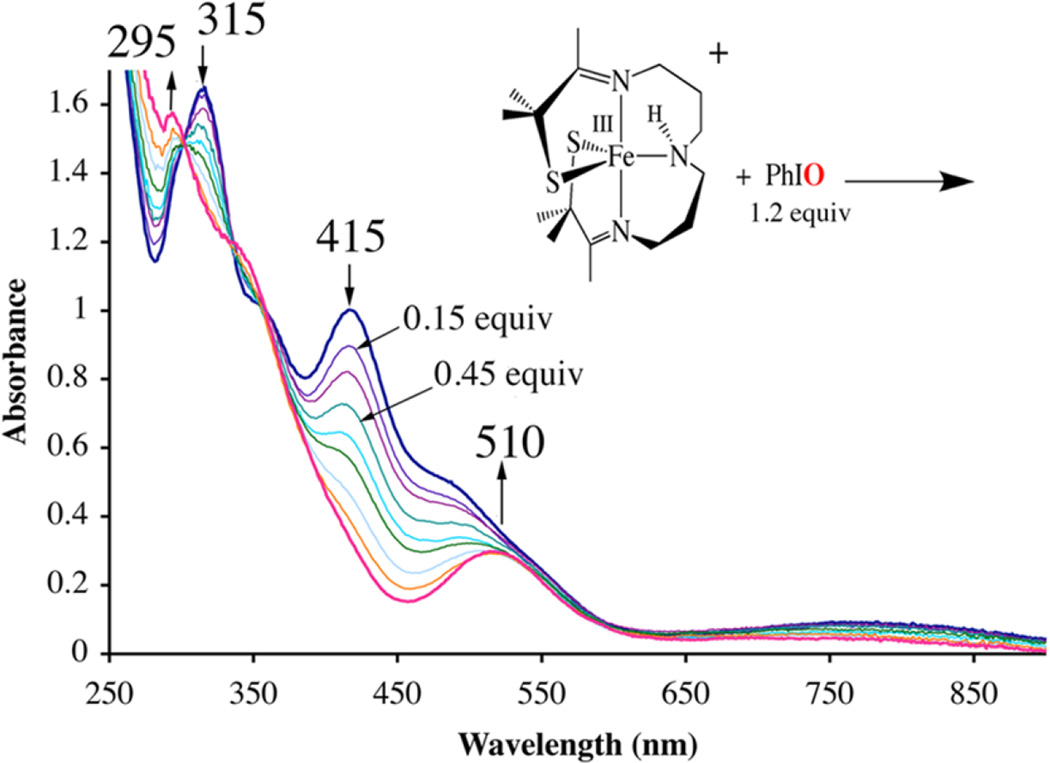

Addition of 1.2 equiv of PhIO to five-coordinate [FeIII(S2Me2N3(Pr,Pr))]+ (2)63 at ambient temperatures induces a color change from orange to magenta, and causes the S→Fe charge-transfer (CT) band in the electronic absorption spectrum, at 415 nm (4200 M−1 cm−1) , to disappear, and a new band to grow in at 510 (1540) nm (Figure 2). A red-shifted absorption band would be consistent with an increase in metal ion Lewis acidity, as a consequence of oxo atom addition. Electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) of this magenta species, 5, shows a peak at m/z = 401, corresponding to the parent ion M + 16 (Figure S-2), consistent with the addition of a single oxygen atom. Addition of 1 equiv of H2O2(aq) to 2 in MeOH (Figure S-3) affords an identical magenta-colored species (5, λmax = 510 nm (1540 M−1 cm−1)), with an identical ESI mass spectrum, indicative of the addition of a single oxygen atom. Single oxo atom addition to 2 would be consistent with the formation of either a high-valent iron oxo or an iron-sulfenate (FeS(R)-O−) species. The low-temperature (7 K), perpendicular-mode EPR spectrum of 5 (Figure 3) reproducibly displays an intense rhombic signal with g-values of 2.16, 2.10, and 1.97, indicative of an S = 1/2 ground state. The precursor to 5, [FeIII(S2Me2N3(Pr,Pr))]+ (2), is also low-spin S = 1/2, but has distinctly different g-values (g = 2.20, 2.15, and 2.00).63 The ambient-temperature MeOH solution magnetic moment of 5 (µeff = 1.99 µB) is also consistent with an S = 1/2 spin state and indicates that there are no thermally accessible higher spin states in the range 7–300 K. In contrast, 2 has an ambient-temperature magnetic moment of µeff = 3.5 µB, reflecting the thermal accessibility of an S = 3/2 excited state.63 The S = 1/2 ground state of 5 would be consistent with either an Fe(V)93–96 or an Fe(III) oxidation state,48, 54, 59–61, 63, 66, 79, 99 but inconsistent with an even-spin, S = 1 or S = 2 system, thereby ruling out an Fe(IV)═O.

Figure 2.

Use of electronic absorption spectroscopy to monitor the reaction between [FeIII(S2Me2N3(Pr,Pr))]+ (2) and 1.2 equiv of PhIO, added in 0.15 equiv aliquots, in MeOH at 298 K.

Figure 3.

Low-temperature (7 K) X-band EPR spectrum of 5 in CH2Cl2/toluene (1:1) glass.

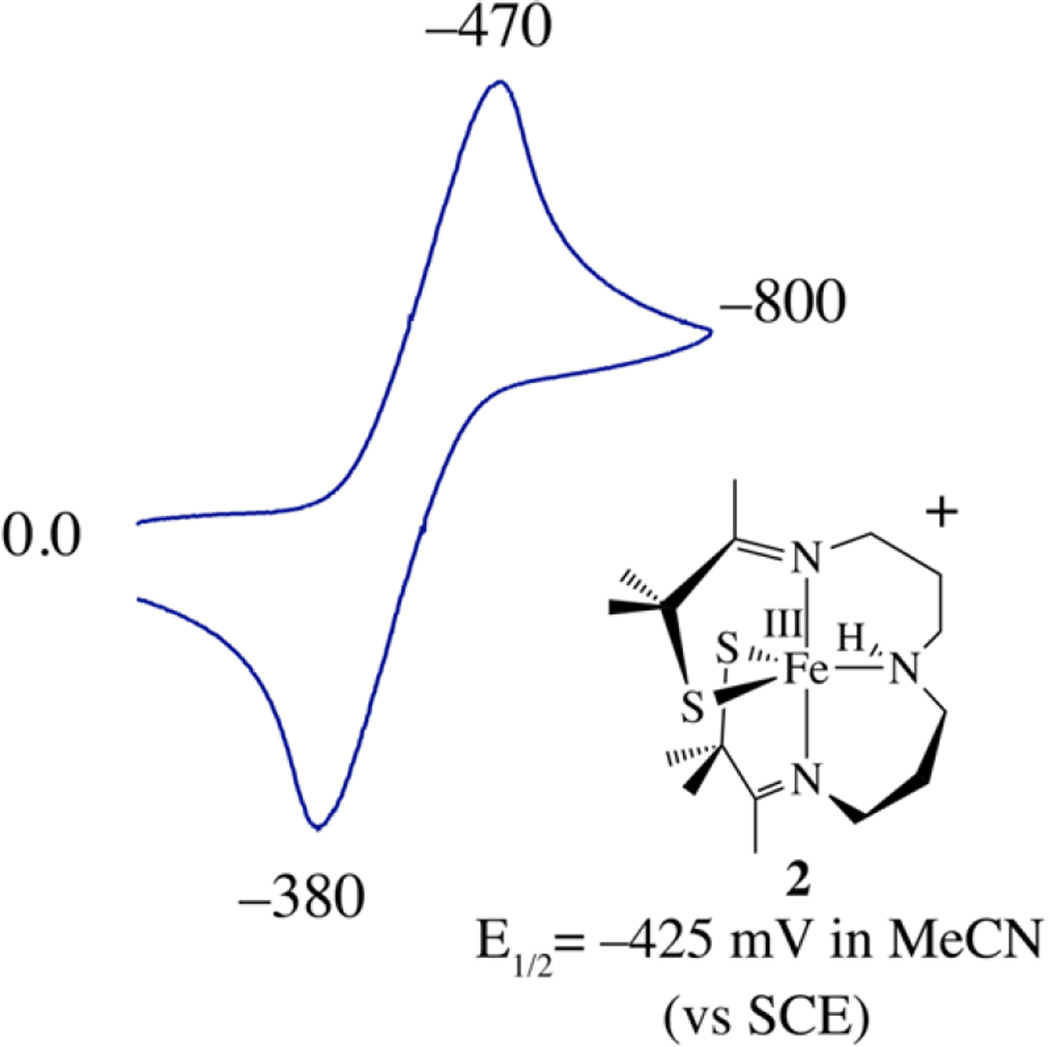

The redox properties of 5 also differ from those of 2. Whereas five-coordinate 2 is reversibly reduced at a potential of E1/2 = −425 mV vs SCE (Figure 4), 5 is irreversibly reduced at a significantly more negative potential (Epc = −958 mV, Epa= −690 mV vs SCE; Figure S-4). Oxygen atom addition therefore increases the stability of the Fe3+ oxidation state. Oxygenation at sulfur would be expected to shift the potential in the opposite direction, given that it would decrease the electron-donating properties of the sulfur, unless, of course, the unmodified thiolate overcompensates for the increase in Lewis acidity by forming a more covalent unmodified Fe–SR bond.48 If the latter were the case, then the S→Fe CT band would blue-shift,48 as opposed to the red-shift shown in Figure 2. On the other hand, ferric ions are more stable in a six-coordinate environment, relative to a five-coordinate environment, perhaps suggesting that oxo atom addition involves the metal ion.

Figure 4.

Cyclic voltammogram of five-coordinate [FeIII(S2Me2N3-(Pr,Pr))]+ (2) in MeCN at 298 K (0.1 M (Bu4N)PF6, glassy carbon electrode, 150 mV/s scan rate). Peak potentials versus SCE are indicated.

Iodosyl benzene (PhIO) typically promotes two-electron chemistry, and has been shown to convert Fe(II) compounds to Fe(IV)═O compounds.98–101 There are fewer examples of Fe(III) compounds that are reactive toward oxo atom donors, such as PhIO (Figure 2). 102–104 One example of the latter involves the addition of PhIO to cytochrome P450 in its Fe(III) resting state, to afford (por/cysS)Fe(V)═O (compound I).105 The oxidizing equivalents of P450 compound I have been shown to be delocalized over both the redox-active porphyrin (por) and the redox-active thiolate ligands. 106–111 Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) has also been shown to convert Fe(III) compounds to Fe(V)═O species,112, 113 or its redox equivalent.107, 109, 111 In contrast to Fe(IV)═O compounds, 52, 98, 114–123 however, very few synthetic non-heme Fe(V)═O species have been observed. 93, 95, 96, 104, 113, 124 The most thoroughly characterized example, [Fe(V)(TAML)(O)]−, incorporates an electron-donating tetra-anionic carboxamide ligand (vide inf ra), TAML4–93, 95, 104, 125, 126.

The IR spectrum of 5 contains a stretch at ν = 1024 cm−1 (Figure S-5) that is absent in the IR spectrum of 2. This stretching frequency would be extremely high for an Fe(V)═O (νFe═O = 798–828 cm−1)96, 127 and is somewhat above the usual range (νS═O = 970–900 cm−1)24, 35, 46, 128–130 for a metal-sulfenate complex Sulfenate νS═O stretches have, however, previously been shown to shift out of the usual range if the RS═O is η2 -coordinated to a metal ion.49, 131 For example, sulfenate/sufinate-ligated [CoIII(η2-SO)(SO2)N3(Pr,Pr)]+ (Scheme 2) has a sulfenate νS═O stretch at 1066 cm−1.49

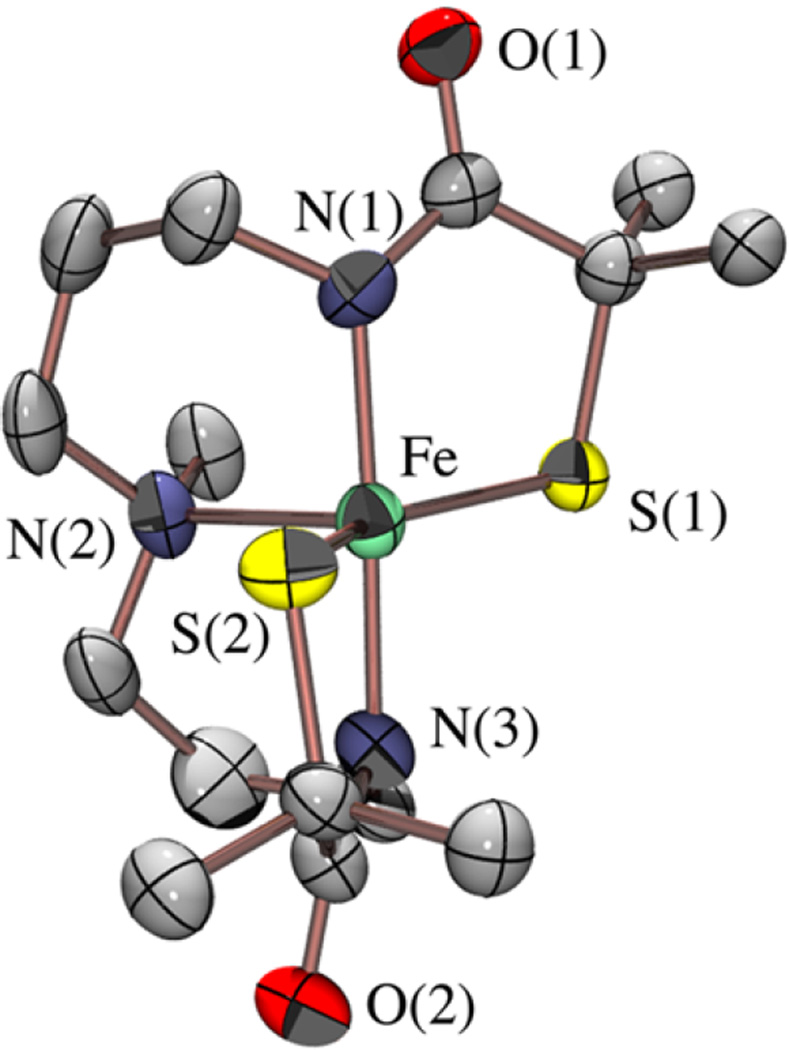

X-ray Structure of [FeIII(η2-SMe2O)(SMe2)N3(Pr,Pr)](PF6) (5)

The identity of the product, 5, formed in the reaction between 2 and PhIO (or H2O2) was ultimately determined by X-ray crystallography. Single crystals of 5 were grown at −30 °C by layering Et2O onto an MeCN solution. As shown in the ORTEP diagram of Figure 5, the single oxygen atom O(1) adds ∼trans (O(1)–Fe–S(2) = 152.3(2)°) to one of the thiolate sulfurs, S(2), and forms a bond to the cis-thiolate S(1), affording an η2-coordinated sulfenate, [FeIII(η2-SMe2O)(SMe2)-N3(Pr,Pr)]+ (5). A similar side-on sulfenate (η2-RSO−) binding mode was observed previously in [CoIII(η2-SO)(SO2)N3-(Pr,Pr)]+ (Scheme 2).49 As mentioned earlier, singly oxygenated metal sulfenates (RSO−) are rare, 24, 48, 49 since they tend to be more reactive than their thiolate precursor. 26, 46, 47, 49 There are significantly more examples of doubly oxygenated, structurally rearranged, oxygen-bound metal-sulfinate (RSO2−) complexes.16–20

Figure 5.

ORTEP diagram of the cation of [FeIII(η2-SMe2O)(SMe2)-N3(Pr,Pr)](PF6) (5) showing the atom labeling scheme. The anion, and all hydrogen atoms have been removed for clarity.

Comparison of structure 5 (Figure 5) with that of its [FeIII(S2Me2N3(Pr,Pr))]+ (2) precursor (Table 2) shows that the singly oxygenated Fe–S(1) bond of 5 elongates only slightly as a result of oxygen atom addition (from 2.133(2) Å in 2 to 2.142(2) Å in 5). One would have expected a more dramatic change in bond length. The Fe–S(2) bond, on the other hand, decreases in length from 2.161(2) Å in 2 to 2.148(2) Å in 5, indicating that the unmodified thiolate compensates for the shifting of electron density away from the metal ion toward the oxygen atom. This compensatory effect was observed previously with [FeIII(ADIT)(ADIT-O)]+ (1; Scheme 2).48 The sulfenate S(1)–O(1) bond in 5 (1.447 Å; Table 2) is slightly shorter than in the few known sulfenate complexes (range: 1.50–1.60 Å),24, 46, 131 including that of [CoIII((η2-SO)(SO2)N3(Pr,Pr))] + (Scheme 2) (S(1)-O(1), 1.548(3) Å).49

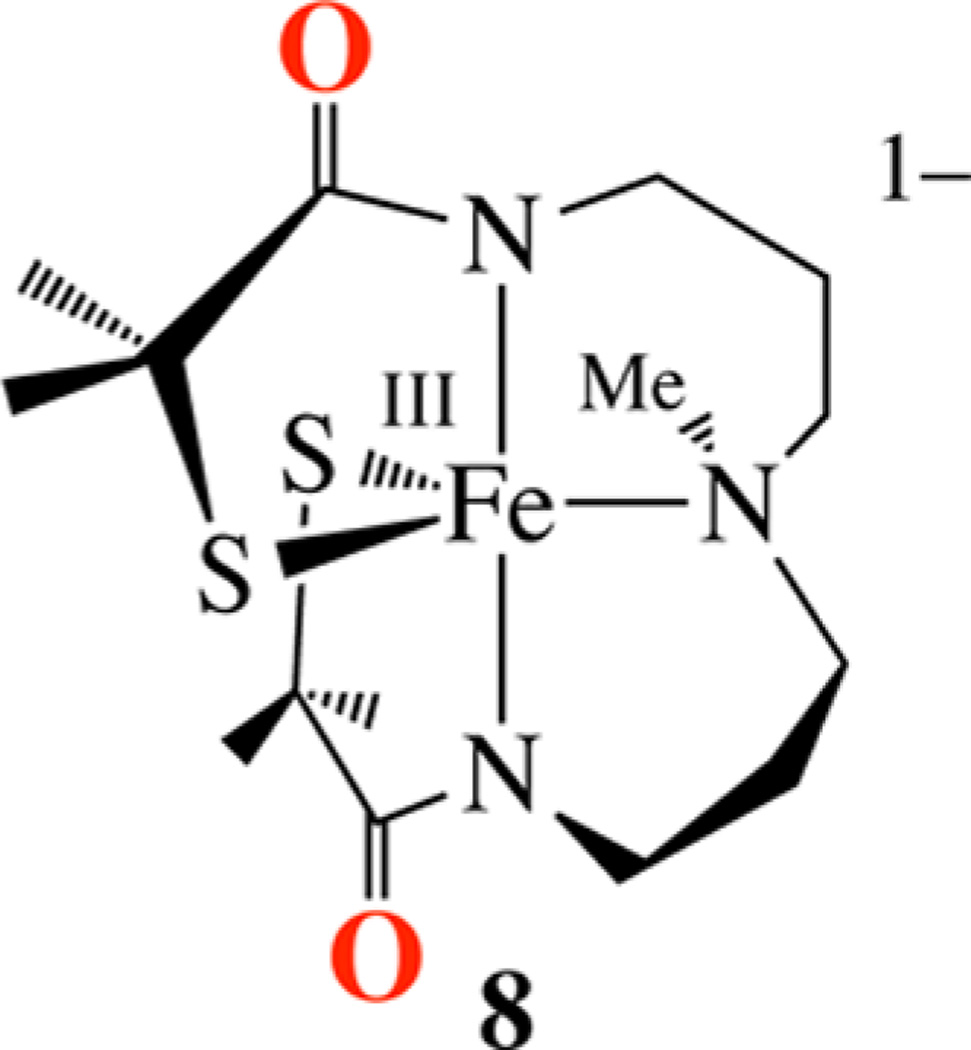

Synthesis of a More Electron-Rich Derivative of 2

In order to provide an even more electron-rich environment, analogous to that of the TAML4− ligand shown previously to stabilize an Fe(V)═O,93 we synthesized (Scheme S-1) the tetra-anionic carboxamide ligand [(Pr,Pr)(NMeNamide2SMe2)]4− (Figures S-6–S-9) and its corresponding Fe-complex (Scheme 5). As mentioned earlier, the preferred 2e− chemistry of PhIO makes it conceivable that oxo atom addition to Fe(III)-2 results in the formation of an unobserved metastable Fe(V)═O intermediate along the reaction pathway to 5. The highly covalent Fe–S bonds would help to delocalize the oxidizing equivalents, thereby making the higher-valent state accessible. The placement of a nucleophilic thiolate cis to an electrophilic oxo would facilitate rapid intramolecular trapping of the oxo via the formation of a S–O bond. A similar reaction sequence was recently observed to convert a sulfur-bound substrate analogue of isopenicillin-N-synthase to an FeII((η2-SO),132 and may be the mechanism by which the catalytically important sulfenate is inserted into the Fe-NHase active site.27

Scheme 5.

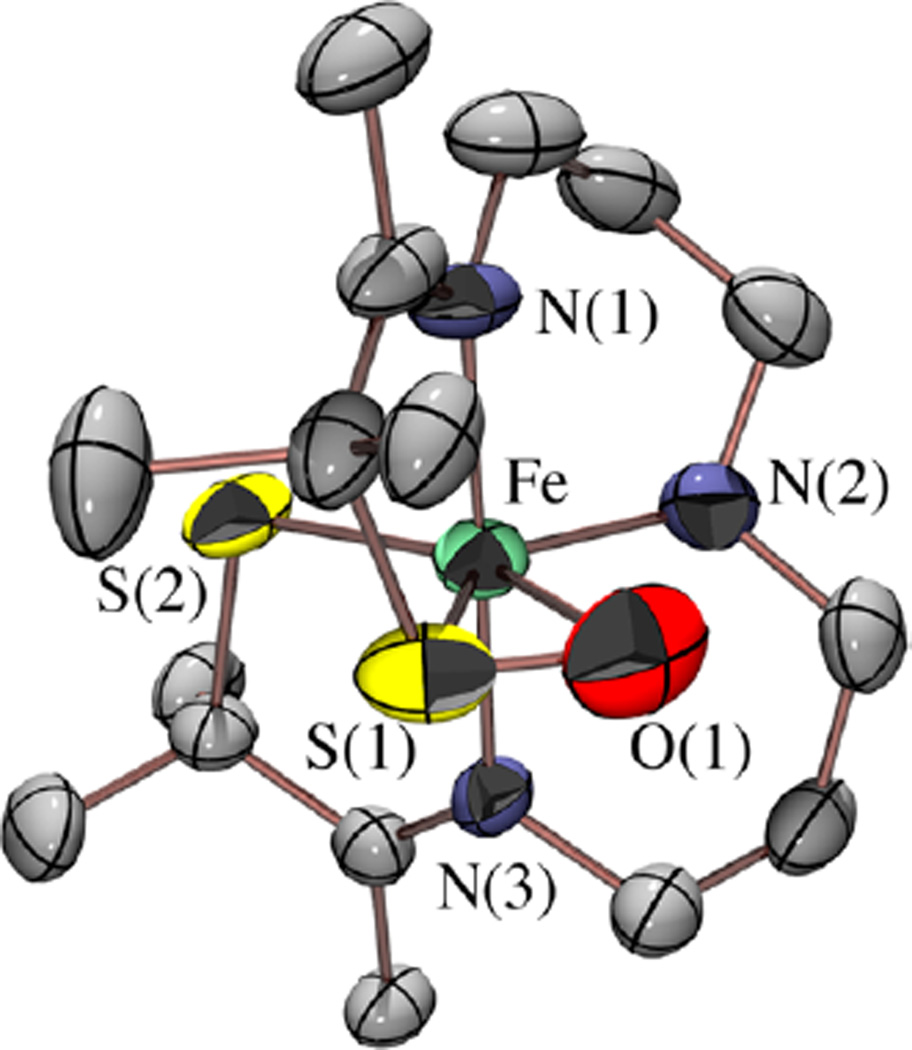

Bis-thiolate/carboxamide-ligated [FeIIIS2Me2NMeN2amide-(Pr,Pr)]− (8) displays a νC═O stretch at 1564 cm−1 (Figure S-11) and a parent ion peak in the negative-mode ESI-MS (Figure S-10). This would be consistent with the structure shown in Scheme 5, which incorporates anionic carboxamides in place of the neutral imines of 2. X-ray-quality crystals of (Et4N)[FeIIIS2Me2NMe N2amide(Pr,Pr)] (8) were obtained via slow vapor diffusion of Et2O into an MeCN solution at −35 °C. As shown in the ORTEP diagram in Figure 6, the Fe3+ ion of 8 maintains a five-coordinate structure, despite being crystallized from a coordinating solvent (MeCN), and resides in a highly distorted N3S2 environment (τ = 0.56) halfway between trigonal bipyramidal and square pyramidal. The Fe3+ ion is ligated by two cis-thiolate sulfurs and a tertiary amine (N(2)) in the equatorial plane, and two trans-carboxamide nitrogens (N(1), N(3)) in apical positions. Key bond distances and angles are compared with those of its cationic imine analogue 2 in Table 2. The incorporation of anionic carboxamides in 8, in place of the neutral imines of 2, causes the mean Fe–S bond distance to significantly elongate (from 2.147 Å in 2 to 2.22 Å in 8). A similar increase in Fe–S bond lengths (from 2.189 to 2.219 Å) is seen upon replacement of the neutral imines in [FeIII(tame-N3)S2Me2)]+ with anionic carboxamides in [FeIII-((tame-N2S)S2Me2)]2−.17 The S–Fe–S angle (144°) in 8 is significantly wider than that of 2 (121°), as well as imine-ligated [FeIII(S2Me2N3(Et,Pr))]+ (105°).61

Figure 6.

ORTEP diagram of the anion of (Et4N)[FeIII-S2Me2NMeN2amide(Pr,Pr)] (8), showing the atom labeling scheme. The cation, and all hydrogen atoms have been removed for clarity.

Carboxamide-ligated 8 is soluble in a variety solvents, including H2O, forms intense olive green-colored solutions, and displays a solvent-independent electronic absorption spectrum with bands at λmax = 352 (8060), 450 (sh), and 584 (1530) nm, indicating that solvents (MeCN, MeOH, H2O (Figure 7)) do not coordinate to the metal ion. The redox potential of anionic 8 (−1.51 V vs SCE; Figure 8) is shifted by over 1 V, relative to that of cationic imine-ligated 2 (E1/2 = −425 mV vs SCE, Figure 4), demonstrating that carboxamide ligands provide significant stability to the Fe3+ oxidation state.133

Figure 7.

Electronic absorption spectrum of (Et4N)[FeIII-S2Me2NMeN2amide(Pr,Pr)] (8) in H2O at 298 K.

Figure 8.

Cyclic voltammogram of (Et4N)[FeIIIS2Me2NMeN2amide-(Pr,Pr)] (8) in MeCN at 298 K (0.1 M (Bu4N)PF6, glassy carbon electrode, 150 mV/s scan rate). Peak potentials versus SCE are indicated.

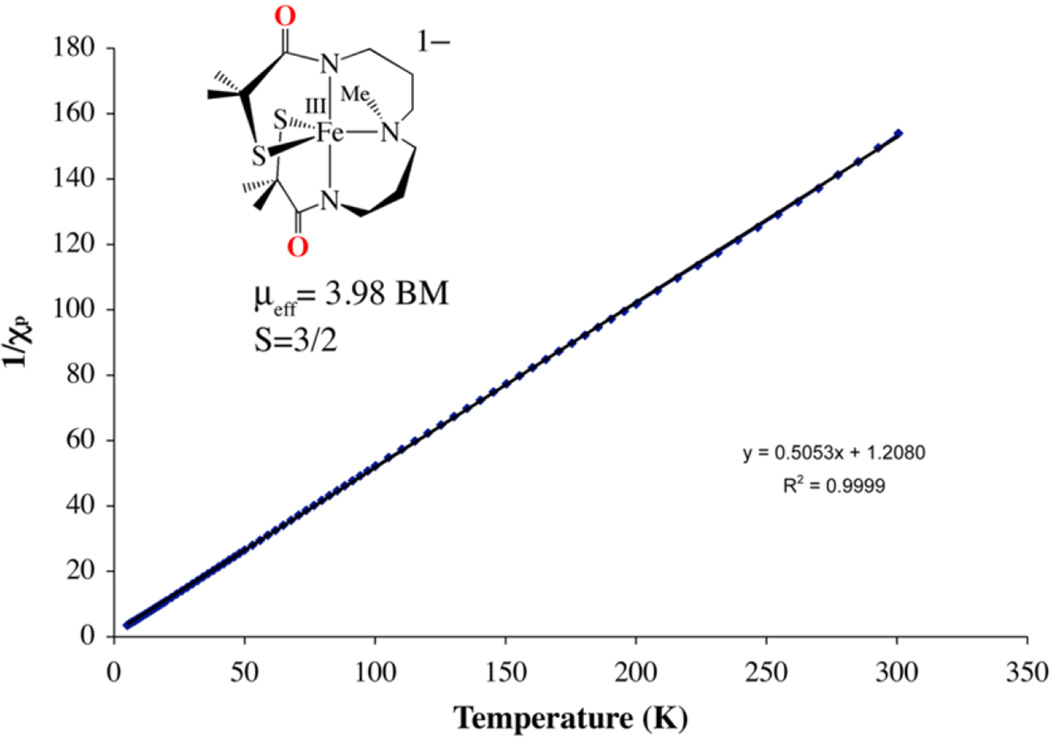

As shown by fits to the inverse magnetic susceptibility (1/ χm) versus temperature plot of Figure 9, and low-temperature (7 K) perpendicular-mode EPR (g = 4.72, 2.82, 1.92; (Figure S-12), bis-thiolate-ligated 8 has an S = 3/2 ground state, and maintains this spin state over a wide temperature range in the solid state and in frozen solution. The ambient-temperature MeCN solution magnetic moment of µeff = 3.75 µB indicates that 8 maintains this spin state in solution. In contrast, imine-ligated 2 has an S = 1/2 ground state, with a thermally accessible S = 3/2 state that is ∼23% populated at ambient temperature and 11% populated at T = −80 °C. Spin states have been shown to influence reactivity in profound ways.134, 135

Figure 9.

Inverse molar magnetic susceptibility (1/χm) vs temperature (T) plot for (Et4N)[FeIIIS2Me2NMeN2amide(Pr,Pr)] (8), fit to an S = 3/2 spin state.

Comparison of the Reactivity Properties of Carbox-amide-Ligated 8 versus Imine-Ligated 2

In contrast to 2, carboxamide-ligated 8 does not react with oxo atom donors PhIO or H2O2, under any conditions, even with a ∼ 1000-fold excess of oxidant, and over a wide temperature range (−78 to +25 °C). One would have anticipated that the thiolates of 8 would be more readily oxygenated, given the anionic molecular charge, and expected increase in electron density on the thiolate sulfurs. Given the similarity of its ligand environment to that of [Fe(V)(TAML)(O)]−, one would have also anticipated that an Fe(V)═O might be stabilized, possibly to the point where it might be observable, prior to intramolecular trapping and S−O bond formation. If, on the other hand, sulfur oxidation involves direct attack at the thiolate sulfurs, then one would also expect carboxamide-ligated 8 to be more reactive toward oxo atom donors than 2, because the thiolate sulfurs should carry more negative charge. In order to determine whether the latter is indeed the case, and quantify this difference if it exists, we turned to theoretical calculations. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed on both 2 and 8, and metrical parameters of the DFT-optimized geometry are reproduced to 0.04 Å of the crystallographically-determined bond lengths (Table S-1). Based on these calculations, the Mulliken charges on the sulfurs of anionic 8 (−0.484 for S(1), −0.488 for S(2)) were found to be roughly twice those of cationic 2 (−0.288 for S(1), −0.245 for S(2)). The longer Fe-S bond distances in 8, relative to 2, would be consistent with this. The calculated average spin-density on the thiolate sulfurs is approximately the same for 2 (0.12) and 8 (0.15). Theoretical calculations therefore suggest that, if oxo atom donors were to directly attack the thiolate sulfur in a 2e–process, then carboxamide-ligated 8 would be more reactive than imine-ligated 2, when in fact the opposite is observed. If a 1e− radical process, involving direct attack at the sulfurs, were involved, then the two complexes 2 and 8 should be equally reactive. Oxo atom donor reactivity does, on the other hand, correlate with ligand binding properties. Despite its open coordination site, anionic 8 does not bind neutral (pyridine, MeCN) or anionic (N3−, CN−) ligands, even when added in excess (>100 equiv) at low temperatures (−40 to −78 °C), as determined using electronic absorption spectroscopy. This is likely due to the fact that a spin-state change would be required in order for five-coordinate 8 to convert to a six-coordinate structure. Whereas 8 is S = 3/2, six-coordinate, thiolate-ligated ferric complexes are predominantly low-spin S = 1/2.39, 59, 79, 97, 136 As one would expect, calculated unpaired spindensity on the iron of 8 (2.59) is significantly larger than that of 2 (0.83), reflecting the S = 1/2 ground state of 2. A Me group on N(2) of 8, in place of the N(2)-H proton of 2, also likely inhibits ligands from binding to 8, since it would sterically clash with S(1) when the S(1)−Fe−N(2) bond angle decreased as a consequence of a the concomitant geometry change (∼trigonal bipyriamidal → ∼octahedral). Imine-ligated 2, on the other hand, readily binds both N3− and NO to its open coordination site,63, 78 in addition to reacting with oxo atom donors.

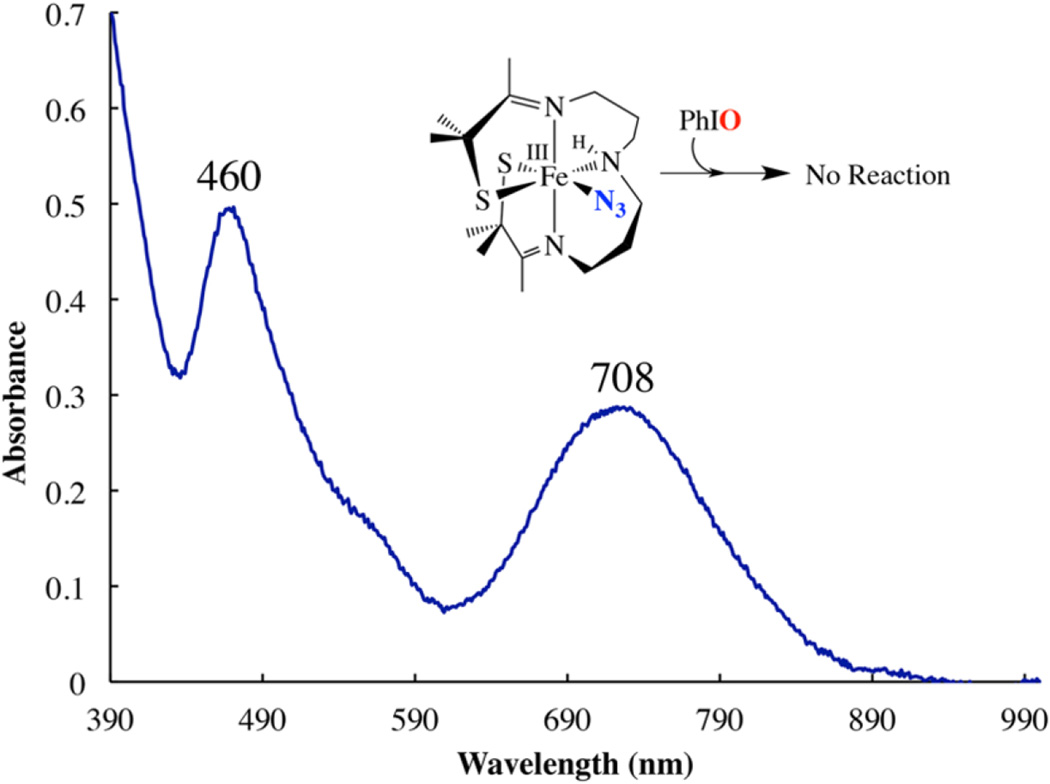

Thus, both correlations between sulfur oxidation and the molecule’s affinity for a sixth ligand and ability to undergo a geometry change, and theoretical calculations, suggest that the mechanism of sulfur oxidation with 2 involves initial coordination of the oxo atom donor to the metal ion. Consistent with this, azide (N3−) is found to inhibit sulfur oxidation with 2. If 1.2 equiv of N3− is added to 2 in THF at −73 °C, then the intense band at 415 (4200) nm, characteristic of 2, is replaced by a band at 708 (1600) nm (Figure 10), characteristic of coordinatively saturated, azide-bound [FeIII-(S2Me2N3(Pr,Pr))(N3)] (4).63 If, following the formation of azide-bound 4 in THF, 1.2 equiv of PhIO is added, no reaction is observed, even after prolonged reaction times (2 h). If, under the same conditions (−73 °C in THF), 1.2 equiv of PhIO is added to 2, in the absence of N3−, then a metastable intermediate that converts to singly oxygenated [FeIII(η2-SMe2O)(SMe2N3(Pr,Pr)]+ (5) (λmax = 510 nm (1540 M−1 cm−1)) forms within minutes (vide inf ra). Thus, azide inhibits sulfur oxidation with 2, presumably by preventing the oxo atom donor from binding to the metal ion. Consistent with this, we observe an intermediate in the oxo atom donor reaction in the absence of azide.

Figure 10.

Monitoring the addition of iodosylbenzene (PhIO) to [FeIII(S2Me2N3(Pr,Pr))N3] (4) in MeOH at −73 °C via electronic absorption spectroscopy, showing that no reaction occurs.

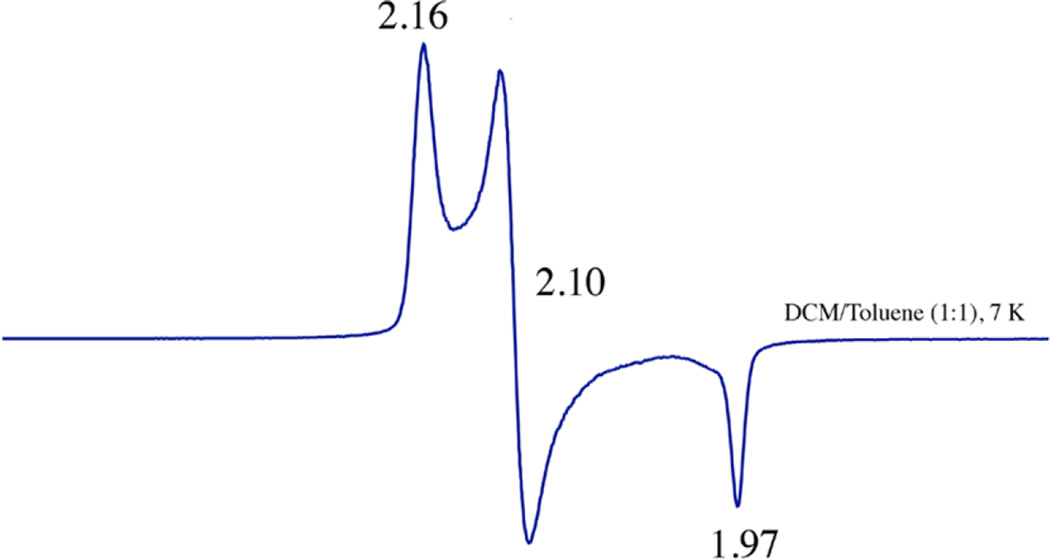

Observation of an Intermediate in the Reaction between Imine-Ligated 2 and Oxo Atom Donors PhIO and IBX-Ester

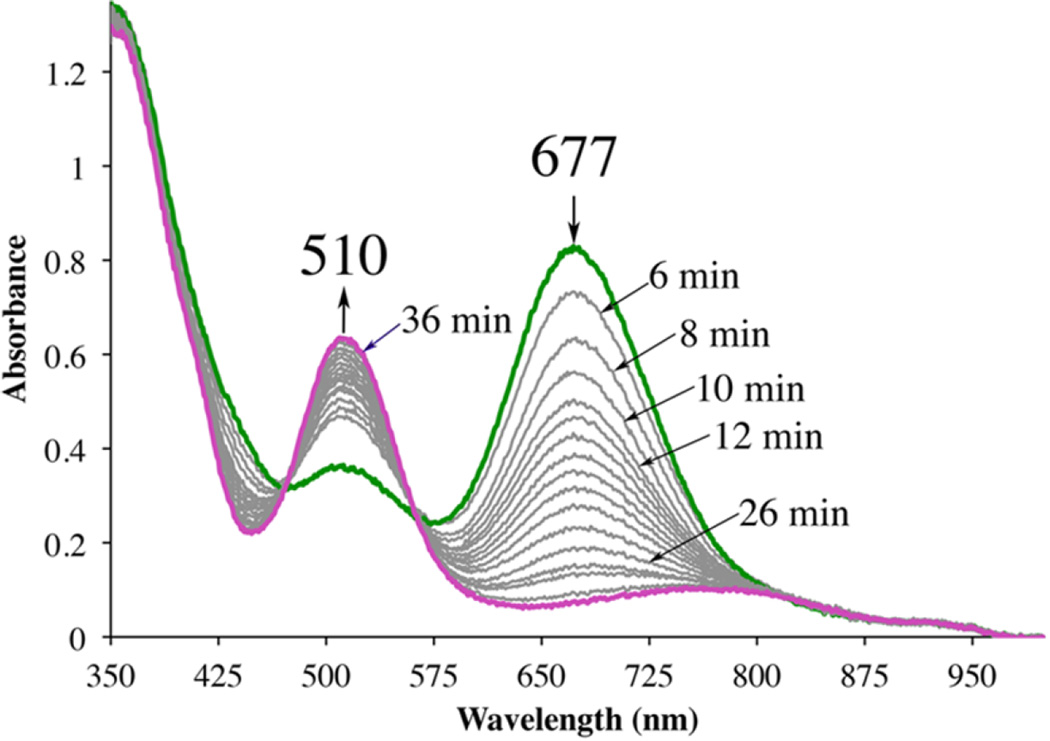

If the reaction between 10 equiv of PhIO and five-coordinate 2 is monitored by electronic absorption spectroscopy at low temperatures (−73 °C) in MeOH, a green intermediate with λmax = 675 nm is observed (Figure S-13), which then slowly (t = 360 min, [2] = 0.238 mM) converts to sulfenate-ligated 5 (Figure S-14). As shown in Figure 11, an approximately identical intermediate (λmax = 677 nm) is formed when IBX-ester is used in place of PhIO; however, its rate of conversion to sulfenate-ligated 5 (36 min, [2] = 0.238 mM) is significantly faster. IBX-ester contains an IV(═O)2 moiety137, whereas PhIO contains an IIII═O moiety, providing a possible explanation for the differences in rates. The observation of intermediates in these reactions provides evidence that sulfur oxidation is assisted by the metal ion, and involves the initial binding of oxo-atom donors to Fe. Clear isosbestic points visible during the IBX reactions show that the new intermediate is stoichiometrically related to complex 2 and converts directly to the sulfenate complex 5, thus eliminating the possibility of direct attack at sulfur. Whether the green intermediate is an oxo atom donor adduct, Fe-O═I-Ph, or an Fe(V)═O remains to be determined. Given how rare Fe-O═I-Ph138, 139 and Fe(V)═ O93, 113, 124 species are, both possibilities are intriguing. The λmax of our green intermediate (677 nm) is in the reported range for both an Fe(III)-O═I-Ph (λmax = 660 nm)139 and Fe(V)═O (λmax = 630 nm (5400 M−1 cm−1)),93, 104 consistent with either possibility. Iodosylarene adducts have been shown to be competent oxidants in oxygen-atom-transfer reactions.138–142 Spectroscopic characterization of the green intermediate, along with the kinetics of both its formation and conversion to sulfenate-ligated 5, will be the topic of a separate manuscript. Possible mechanisms for sulfur oxygenation would involve initial formation of an oxo atom donor adduct Fe-O═I-Ph that is either directly attacked by the adjacent nucleophilic sulfur, or that converts first to an Fe(V)═O, which is then rapidly and irreversibly trapped by the adjacent sulfur. The observation of one intermediate, as opposed to two, is consistent with either (a) rate-determining cis-migration of a thiolate sulfur to the oxo of a coordinated Fe-O═I-Ph, or (b) rate-determining cleavage of the I-O to afford an unobserved Fe(V)═O suggesting that the intermediate is likely an oxo atom donor adduct. The virtually identical electronic spectra associated with the green intermediate, regardless of the nature of the oxo atom donor, is a bit puzzling, given that one would expect an Fe-O═IV-Ph species to have electronic properties that differ from those of an Fe-O═IIII-Ph species. Inhibition studies, involving PhI, should help to distinguish mechanisms (a) and (b). The anticipated rapid rate of intramolecular trapping of an Fe(V)═O, relative to the likely rate of its formation, would suggest that it would be unobservable. This remains to be determined, however.

Figure 11.

Detection of a green metastable intermediate in the reaction between (Pr,Pr)Fe(III) (2) and 10 equiv of IBX-ester at −73 °C in MeOH to form sulfenate 5 over the course of 36 min.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

Cysteinate oxygenation is intimately tied to the function of both cysteinate dioxygenases (CDOs)1–8 and nitrile hydratases (NHases).31, 39–41 However, the mechanism by which sulfurs are oxidized by these enzymes is unknown, in part because intermediates have yet to be observed. Herein we show that oxo atom donors, PhIO and H2O2, react with coordinatively unsaturated [FeIII(S2Me2N3(Pr,Pr))]+ (2) to afford a rare example of a singly oxygenated sulfenate, [FeIII(η2-SMe2O)-(SMe2)N3(Pr,Pr)]+ (5). Sulfenate-ligated 5 is low-spin (S = 1/2; g = 2.17, 2.11, 1.98) and resembles both an intermediate proposed to form during CDO-catalyzed cysteine oxidation and the catalytically essential NHase Fe-SCys114-O, proposed to be intimately involved in its mechanism.27, 31, 42, 43 In contrast to imine-ligated 2, carboxamide-ligated [FeIIIS2Me2NMeN2amide-(Pr,Pr)]− (8) was shown to be unreactive toward oxo atom donors PhIO or H2O2, under any conditions. DFT-calculated Mulliken charges on the sulfurs of anionic 8 were found to be roughly twice as negative as those of cationic 2, indicating that if oxo atom donors were to directly attack the thiolate sulfur, then carboxamide-ligated 8 would be more reactive than imine-ligated 2. Reactivity was shown to correlate with the metal ion’s ability to bind exogenous ligands, and azide (N3−) was found to inhibit sulfur oxidation with 2, suggesting that the mechanism of sulfur oxidation involves initial coordination of the oxo atom donor to the metal ion. Consistent with this, a green intermediate is observed to form, which then slowly converts to sulfenate-ligated 5. Whether the green intermediate is an oxo atom donor adduct, Fe-O═I-Ph, or an Fe(V)═O remains to be determined. The placement of a nucleophilic thiolate cis to an electrophilic oxo would facilitate rapid intramolecular trapping of a high-valent oxo via the formation of an S–O bond. Although the direct involvement of the metal ion has been theoretically calculated to provide a lower energy pathway to sulfur oxygenation by CDO,5 this has not been experimentally proven.7

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIH (GM45881). P.L.-M. gratefully acknowledges support by an NIH pre-doctoral minority fellowship (F31 GM73583-01). We also gratefully acknowledge Stephen J. Lippard, and an anonymous donor for financial support, and Xiaosong Li and Joe Kasper for help with the DFT calculations.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

X-ray crystallographic data for 5 (CIF)X-ray crystallographic data for 8 (CIF)Experimental details regarding the synthesis and characterization of the [(Pr,Pr)(NMeHNamide2MeSH)2)]. HCl ligand; ESI-MS, IR, and CV of 5; ESI-MS, IR, CV, aqueous electronic absorption, and EPR spectra of 8; electronic spectral evidence for the formation of 5 via a green metastable intermediate; crystallographic tables for 5 and 8; and metrical parameters for DFT-optimized structures, including Scheme S-1, Figures S1-1–Figure S-14, and Tables S-1–S-11 (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kumar D, Sastry GN, Goldberg DP, de Visser SP. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2012;116:582–591. doi: 10.1021/jp208230g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McQuilken AC, Jiang Y, Siegler MA, Goldberg DP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:8758–8761. doi: 10.1021/ja302112y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Badiei YM, Siegler MA, Goldberg DP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:1274–1277. doi: 10.1021/ja109923a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jiang Y, Widger LR, Kasper GD, Siegler MA, Goldberg DP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:12214–12215. doi: 10.1021/ja105591q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kumar D, Thiel W, de Visser SP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:3869–3882. doi: 10.1021/ja107514f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aluri S, de Visser SP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:14846–14847. doi: 10.1021/ja0758178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simmons CR, Krishnamoorthy K, Granett SL, Schuller DJ, Dominy JE, Jr, Begley TP, Stipanuk MH, Karplus PA. Biochemistry. 2008;47:11390–11392. doi: 10.1021/bi801546n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ray K, Pfaff FF, Wang B, Nam W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:13942–13958. doi: 10.1021/ja507807v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heafield MT, Fearn S, Steventon GB, Waring RH, Williams AC, Sturman SG. Neurosci. Lett. 1990;110:216–220. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(90)90814-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Driggers CM, Stipanuk MH, Karplus PA. Encyclopedia of Inorganic and Bioinorganic Chemistry. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2015. Mammalian Cysteine Dioxygenase; pp. 1–11. [Online] http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/book/10.1002/9781119951438. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brait M, Ling S, Nagpal JK, Chang X, Park HL, Lee J, Okamura J, Yamashita K, Sidransky D, Kim MS. PLoS One. 2012;7:e44951. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jeschke J, O’Hagan HM, Zhang W, Vatapalli R, Freitas Calmon M, Danilova L, Nelkenbrecher C, Van Neste L, Bijsmans IT, G W, Van Engeland M, Gabrielson E, Schuebel KE, Winterpacht A, Baylin SB, Herman JG, Ahuja N. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013;19:3201–3211. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chiang C-W, Kleespies ST, Stout HD, Meier KK, Li P-Y, Bominaar EL, Que L, Jr, Münck E, Lee W-Z. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:10846–10849. doi: 10.1021/ja504410s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hong S, Sutherlin KD, Park J, Kwon E, Siegler MA, Solomon EI, Nam W. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:5440. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sahu S, Goldberg DP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:11410–11428. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b05251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harrop TC, Mascharak PK. Acc. Chem. Res. 2004;37:253–260. doi: 10.1021/ar0301532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lugo-Mas P, Taylor W, Schweitzer D, Theisen RM, Xu L, Shearer J, Swartz RD, Gleaves MC, DiPasquale A, Kaminsky W, Kovacs JA. Inorg. Chem. 2008;47:11228–11236. doi: 10.1021/ic801704n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Noveron JC, Olmstead MM, Mascharak PK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:3247–3259. doi: 10.1021/ja001253v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tyler LA, Noveron JC, Olmstead MM, Mascharak PK. Inorg. Chem. 2000;39:357–362. doi: 10.1021/ic990794m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heinrich L, Li Y, Vaissermann J, Chottard G, Chottard J-C. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1999;38:3526–3528. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1521-3773(19991203)38:23<3526::aid-anie3526>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sallmann M, Siewert I, Fohlmeister L, Limberg C, Knispel C. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012;51:2234–2237. doi: 10.1002/anie.201107345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McQuilken AC, Goldberg DP. Dalton Trans. 2012;41:10883–10899. doi: 10.1039/c2dt30806a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Widger LR, Jiang Y, Siegler MA, Kumar D, Latifi R, de Visser SP, Jameson GNL, Goldberg DP. Inorg. Chem. 2013;52:10467–10480. doi: 10.1021/ic4013558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grapperhaus CA, Darensbourg MY. Acc. Chem. Res. 1998;31:451–459. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leonard SE, Reddie KG, Carroll KS. ACS Chem. Biol. 2009;4:783–799. doi: 10.1021/cb900105q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Claiborne A, Yeh JI, Mallett TC, Luba J, Crane EJ, Charrier V, Parsonage D. Biochemistry. 1999;38:15407–15416. doi: 10.1021/bi992025k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Light KM, Yamanaka Y, Odaka M, Solomon EI. Chem. Sci. 2015;6:6280–6294. doi: 10.1039/c5sc02012c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hashimoto K, Suzuki H, Taniguchi K, Noguchi T, Yohda M, Odaka M. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:36617–36623. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806577200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murakami T, Nojiri M, Nakayama H, Odaka M, Yohda M, Dohmae N, Takio K, Nagamune T, Endo I. Protein Sci. 2000;9:1024–1030. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.5.1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nojiri M, Yohda M, Odaka M, Matsushita Y, Tsujimura M, Yoshida T, Dohmae N, Takio K, Endo I. J. Biochem. 1999;125:696–704. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martinez S, Wu R, Sanishvili R, Liu D, Holz R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:1186–1189. doi: 10.1021/ja410462j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yeh JI, Claiborne A, Hol WGI. Biochemistry. 1996;35:9951–9957. doi: 10.1021/bi961037s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chae HZ, Robison K, Poole LB, Church G, Storz G, Rhee SG. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1994;91:7017–7021. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.15.7017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mitra S, Holz RC. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:7397–7404. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604117200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Noguchi T, Nojiri M, Takei K, Odaka M, Kamiya N. Biochemistry. 2003;42:11642–11650. doi: 10.1021/bi035260i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kobayashi M, Shimizu S. Nat. Biotechnol. 1998;16:733–736. doi: 10.1038/nbt0898-733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sugiura Y, Kuwahara J, Nagasawa T, Yamada H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987;109:5848–5850. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stolz A, Trott S, Binder M, Bauer R, Hirrlinger B, Layh N, Knackmuss H-J. J. Mol. Catal. B: Enzym. 1998;5:137–141. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dey A, Chow M, Taniguchi K, Lugo-Mas P, Davin SD, Maeda M, Kovacs JA, Odaka M, Hedman B, Hodgson KO, Solomon EI. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:533–541. doi: 10.1021/ja0549695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Song L, Wang M, Shi J, Xue Z, Wang M-X, Qian S. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007;362:319–324. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.07.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nagashima S, Nakasako M, Dohmae N, Tsujimura M, Takio K, Odaka M, Yohda M, Kamiya N, Endo I. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1998;5:347–351. doi: 10.1038/nsb0598-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tsujimura M, Odaka M, Nakayama H, Dohmae N, Koshino H, Asami T, Hoshino M, Takio K, Yoshida S, Maeda M, Endo I. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:11532. doi: 10.1021/ja035018z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yamanaka Y, Kato Y, Hashimoto K, Iida K, Nagasawa K, Nakayama H, Dohmae N, Noguchi K, Noguchi T, Yohda M, Odaka M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015;54:10763–10767. doi: 10.1002/anie.201502731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goto K, Holler M, Okazaki R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:1460–1461. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Allison WS. Acc. Chem. Res. 1976;9:293–299. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Adzamli IK, Libson K, Lydon JD, Elder RC, Deutsch E. Inorg. Chem. 1979;18:303–311. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bachi MD, Gross A. J. Org. Chem. 1982;47:897–898. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lugo-Mas P, Dey A, Xu L, Davin SD, Benedict J, Kaminsky W, Hodgson KO, Hedman B, Solomon EI, Kovacs JA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:11211–11221. doi: 10.1021/ja062706k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kung IY, Schweitzer D, Shearer J, Taylor WD, Jackson HL, Lovell S, Kovacs JA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:8299–8300. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Coggins MK, Sun X, Kwak Y, Solomon EI, Rybak-Akimova EV, Kovacs JA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:5631–5640. doi: 10.1021/ja311166u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Theisen RM, Shearer J, Kaminsky W, Kovacs JA. Inorg. Chem. 2004;43:7682–7690. doi: 10.1021/ic0491884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kovacs JA. Science. 2003;299:1024–1025. doi: 10.1126/science.1081792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kitagawa T, Dey A, Lugo-Mas P, Benedict J, Kaminsky W, Solomon E, Kovacs JA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:14448–14449. doi: 10.1021/ja064870d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shearer J, Scarrow RC, Kovacs JA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:11709–11717. doi: 10.1021/ja012722b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kovacs JA. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015;48:2744–2753. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Coggins MK, Martin-Diaconescu V, De Beer S, Kovacs JA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:4260–4272. doi: 10.1021/ja308915x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Coggins MK, Brines LM, Kovacs JA. Inorg. Chem. 2013;52:12383–12393. doi: 10.1021/ic401234t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Coggins MK, Kovacs JA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:12470–12473. doi: 10.1021/ja205520u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kovacs JA, Brines LM. Acc. Chem. Res. 2007;40:501–509. doi: 10.1021/ar600059h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kovacs JA. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:825–848. doi: 10.1021/cr020619e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schweitzer D, Shearer J, Rittenberg DK, Shoner SC, Ellison JJ, Loloee R, Lovell SC, Barnhart D, Kovacs JA. Inorg. Chem. 2002;41:3128–3136. doi: 10.1021/ic0109187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shoner SC, Nienstedt A, Ellison JJ, Kung I, Barnhart D, Kovacs JA. Inorg. Chem. 1998;37:5721–5725. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ellison JJ, Nienstedt A, Shoner SC, Barnhart D, Cowen JA, Kovacs JA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:5691–5700. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shearer J, Nehring J, Lovell S, Kaminsky W, Kovacs JA. Inorg. Chem. 2001;40:5483–5484. doi: 10.1021/ic010221l. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shearer J, Fitch SB, Kaminsky W, Benedict J, Scarrow RC, Kovacs JA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:3671–3676. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0637029100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shearer J, Jackson HL, Schweitzer D, Rittenberg DK, Leavy TM, Kaminsky W, Scarrow RC, Kovacs JA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:11417–11428. doi: 10.1021/ja012555f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Theisen R, Shearer J, Kaminsky W, Kovacs J. Inorg. Chem. 2004;43:7682–7690. doi: 10.1021/ic0491884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Grapperhaus CA, Li M, Patra AK, Poturovic S, Kozlowski PM, Zgierski MZ, Mashuta MS. Inorg. Chem. 2003;42:4382–4388. doi: 10.1021/ic026239t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Namuswe F, Kasper GD, Sarjeant AAN, Hayashi T, Krest CM, Green MT, Moenne-Loccoz P, Goldberg DP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:14189–14200. doi: 10.1021/ja8031828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jiang Y, Telser J, Goldberg DP. Chem. Commun. 2009:6828–6830. doi: 10.1039/b913945a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shearer J, Nehring J, Lovell S, Kaminsky W, Kovacs J. Inorg. Chem. 2001;40:5483–5484. doi: 10.1021/ic010221l. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Brines LM, Shearer J, Fender JK, Schweitzer D, Shoner SC, Barnhart D, Kaminsky W, Lovell S, Kovacs JA. Inorg. Chem. 2007;46:9267–9277. doi: 10.1021/ic701433p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Brines LM, Villar-Acevedo G, Kitagawa T, Swartz RD, Lugo-Mas P, Kaminsky W, Benedict JB, Kovacs JA. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 2008;361:1070–1078. doi: 10.1016/j.ica.2007.07.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shearer J, Kung I, Lovell S, Kovacs JA. Inorg. Chem. 2000;39:4998–4999. doi: 10.1021/ic0005689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Theisen RM, Kovacs JA. Inorg. Chem. 2005;44:1169–1171. doi: 10.1021/ic048818z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Villar-Acevedo G, Nam E, Fitch S, Benedict J, Freudenthal J, Kaminsky W, Kovacs JA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:1419–1427. doi: 10.1021/ja107551u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nam E, Alokolaro PE, Swartz RD, Gleaves MC, Pikul J, Kovacs JA. Inorg. Chem. 2011;50:1592–1602. doi: 10.1021/ic101776m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Schweitzer D, Ellison JJ, Shoner SC, Lovell S, Kovacs JA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:10996–10997. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kennepohl P, Neese F, Schweitzer D, Jackson HL, Kovacs JA, Solomon EI. Inorg. Chem. 2005;44:1826–1836. doi: 10.1021/ic0487068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Shearer J, Kung IY, Lovell S, Kaminsky W, Kovacs JA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:463–468. doi: 10.1021/ja002642s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Live DH, Chan SI. Anal. Chem. 1970;42:791. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Evans DA. J. Chem. Soc. 1959:2003–2005. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Van Geet AL. Anal. Chem. 1968;40:2227–2229. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Neese F. Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Mol. Sci. 2012;2:73–78. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Becke AD. Phys. Rev. A: At., Mol., Opt. Phys. 1988;38:3098–3100. doi: 10.1103/physreva.38.3098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Perdew JP. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 1986;33:8822–8224. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.33.8822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Weigend F. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2006;8:1057–1065. doi: 10.1039/b515623h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Grimme S, Ehrlich S, Goerigk L. J. Comput. Chem. 2011;32:1456–1465. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lenthe EV, Avoird AVD, Wormer PES. J. Chem. Phys. 1998;108:4783–4796. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Weigend F, Ahlrichs R. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2005;7:3297–3305. doi: 10.1039/b508541a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Klamt A, Schüürmann GJ. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2. 1993;5:799–805. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Waasmaier D, Kirfel A. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. A: Found. Crystallogr. 1995;51:416. [Google Scholar]

- 93.de Oliveira FT, Chanda A, Banerjee D, Shan X, Mondal S, Que L, Jr, Bominaar EL, Münck E, Collins TJ. Science. 2007;315:835–838. doi: 10.1126/science.1133417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lyakin OY, Zima AM, Samsonenko DG, Bryliakov KP, Talsi EP. ACS Catal. 2015;5:2702–2707. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ghosh M, Singh KK, Panda C, Weitz A, Hendrich MP, Collins TJ, Dhar BB, Gupta SS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:9524–9527. doi: 10.1021/ja412537m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Van Heuvelen KM, Fiedler AT, Shan X, De Hont RF, Meier KK, Bominaar EL, Münck E, Que L., Jr Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012;109:11933–11938. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206457109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Jackson HL, Shoner SC, Rittenberg D, Cowen JA, Lovell S, Barnhart D, Kovacs JA. Inorg. Chem. 2001;40:1646–1653. doi: 10.1021/ic001271d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Que L., Jr Acc. Chem. Res. 2007;40:493–500. doi: 10.1021/ar700024g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Rohde J-U, In JH, Lim MH, Brennessel WW, Bukowski MR, Stubna A, Münck E, Nam W, Que L., Jr Science. 2003;299:1037–1039. doi: 10.1126/science.299.5609.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Sastri CV, Park MJ, Ohta T, Jackson TA, Stubna A, Seo MS, Lee J, Kim J, Kitagawa T, Münck E, Que L, Jr, Nam W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:12494–12495. doi: 10.1021/ja0540573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Nam W, Jin SW, Lim MH, Ryu JY, Kim C. Inorg. Chem. 2002;41:3647–3652. doi: 10.1021/ic011145p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Nam W, Choi SK, Lim MH, Rohde J-U, Kim I, Kim J, Kim C, Que L., Jr Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2003;42:109–111. doi: 10.1002/anie.200390036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Groves JT, Watanabe YJ. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988;110:8443–8452. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kundu S, Thompson JVK, Ryabov AD, Collins TJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:18546–18549. doi: 10.1021/ja208007w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Meunier B, de Visser SP, Shaik S. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:3947–3980. doi: 10.1021/cr020443g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Rittle J, Green MT. Science. 2010;330:933–937. doi: 10.1126/science.1193478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Krest CM, Onderko EL, Yosca TH, Calixto JC, Karp RF, Livada J, Rittle J, Green MT. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:17074–17081. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R113.473108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Wang X, Peter S, Kinne M, Hofrichter M, Groves JT. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:12897–12900. doi: 10.1021/ja3049223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Chreifi G, Baxter EL, Doukov T, Cohen AE, McPhillips SE, Song J, Meharenna YT, Soltis SM, Poulos TL. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2016;113:1226–1231. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1521664113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Barrows TP, Poulos TL. Biochemistry. 2005;44:14062–14068. doi: 10.1021/bi0507128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Denisov IG, Makris TM, Sligar SG, Schlichting I. Chem. Rev. 2005;105:2253–2277. doi: 10.1021/cr0307143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Oloo WN, Que L., Jr Acc. Chem. Res. 2015;48:2612–2621. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Prat E, Mathieson JS, Güell M, Ribas X, Luis JM, Cronin L, Costas M. Nat. Chem. 2011;3:788–793. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Decker A, Rohde J-U, Klinker RJ, Wong SD, Que L, Jr, Solomon EI. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:15983–15996. doi: 10.1021/ja074900s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Bukowski MR, Koehntop KD, Stubna A, Bominaar EL, Halfen JA, Münck E, Nam W, Que L. Science. 2005;310:1000–1002. doi: 10.1126/science.1119092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Costas M, Mehn MP, Jensen MP, Que L., Jr Chem. Rev. 2004;104:939–986. doi: 10.1021/cr020628n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Puri M, Que L., Jr Acc. Chem. Res. 2015;48:2443–2452. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Sahu S, Quesne MG, Davies CG, Dürr M, Ivanović-Burmazovic I, Siegler MA, Jameson GNL, de Visser SP, Goldberg DP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:13542–13545. doi: 10.1021/ja507346t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Lacy DC, Gupta R, Stone KL, Greaves J, Ziller JW, Hendrich MP, Borovik AS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:12188–12190. doi: 10.1021/ja1047818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Solomon EI, Wong SD, Liu LV, Decker A, Chow MS. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2009;13:99–113. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Nam W. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015;48:2415–2423. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Thibon A, England J, Martinho M, Young VG, Jr, Frisch JR, Guillot R, Girerd J-J, Münck E, Que L, Jr, Banse F. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:7064–7067. doi: 10.1002/anie.200801832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Hohenberger J, Ray K, Meyer K. Nat. Commun. 2012;3:720. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.McDonald AR, Que L., Jr Nat. Chem. 2011;3:761–762. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Kundu S, Thompson JVK, Shen LQ, Mills MR, Bominaar EL, Ryabov AD, Collins TJ. Chem. - Eur. J. 2015;21:1803–1810. doi: 10.1002/chem.201405024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Panda C, Debgupta J, Díaz Díaz D, Singh KK, Sen Gupta S, Dhar BB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:12273–12282. doi: 10.1021/ja503753k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Groves JT, Haushalter RC, Nakamura M, Nemo TE, Evans BJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1981;103:2884–2886. [Google Scholar]

- 128.Buonomo RM, Font I, Maguire MJ, Reibenspies JH, Tuntulani T, Darensbourg MY. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:963–973. [Google Scholar]

- 129.Heinrich L, Mary-Verla A, Li Y, Vaissermann J, Chottard JC. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2001;2001:2203–2206. [Google Scholar]

- 130.Lydon JD, Deutsch E. Inorg. Chem. 1982;21:3180–3185. [Google Scholar]

- 131.Cornman CR, Stauffer TC, Boyle PD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:5986–5987. [Google Scholar]

- 132.Ge W, Clifton IJ, Stok JE, Adlington RM, Baldwin JE, Rutledge PJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:10096–10102. doi: 10.1021/ja8005397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Noveron JC, Olmstead MM, Mascharak PK. Inorg. Chem. 1998;37:1138–1139. doi: 10.1021/ic971388a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Costas M, Harvey JN. Nat. Chem. 2013;5:7–9. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Carreon-Macedo J-L, Harvey JN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:5789–5797. doi: 10.1021/ja049346q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Shoner S, Barnhart D, Kovacs JA. Inorg. Chem. 1995;34:4517–4518. [Google Scholar]

- 137.Ye W, Ho DM, Friedle S, Palluccio TD, Rybak-Akimova EV. Inorg. Chem. 2012;51:5006–5021. doi: 10.1021/ic202435r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Lennartson A, McKenzie CJ. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012;51:6767–6770. doi: 10.1002/anie.201202487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Hong S, Wang B, Seo MS, Lee YM, Kim MJ, Kim HR, Ogura T, Garcia-Serres R, Clémancey M, Latour JM, Nam W. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014;53:6388–6392. doi: 10.1002/anie.201402537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Wang C, Kurahashi T, Inomata K, Hada M, Fujii H. Inorg. Chem. 2013;52:9557–9566. doi: 10.1021/ic401270j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Wang SH, Mandimutsira BS, Todd R, Ramdhanie B, Fox JP, Goldberg DP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:18–19. doi: 10.1021/ja038951a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Yang Y, Diederich F, Valentine JS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990;112:7826–7828. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.