Abstract

Alcohol is a leading cause of liver disease worldwide. Although alcohol abstinence is the crucial therapeutic goal for patients with alcoholic liver disease, these patients have less access to psychosocial, behavioral and/or pharmacological treatments for alcohol use disorder. Psychosocial and behavioral therapies include 12-step facilitation, brief interventions, cognitive behavioral therapy, and motivational enhancement therapy. In addition to medications approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for alcohol use disorder (disulfiram, naltrexone and acamprosate), recent efforts to identify potential new treatments have yielded promising candidate pharmacotherapies. Finally, more efforts are needed to integrate treatments across disciplines toward patient-centered approaches in the management of patients with alcohol use disorder and alcoholic liver disease.

Keywords: alcohol use disorder, liver disease, alcoholic liver disease, treatment

INTRODUCTION

Despite the mortality and morbidity resulting from alcohol use disorder(1), <10% of patients receive treatment for alcohol use disorder(2). There is a paucity of clinical trials in patients with alcoholic liver disease and little integration of addiction specialists into the medical teams that care for these patients. This deficiency reflects nihilism, stigma, and a failure to link behavioral and traditional medical research.

ALCOHOL USE DISORDER

Neurobiology of Alcohol Use Disorder

Alcohol use disorder is characterized by loss of control over alcohol consumption accompanied by changes in brain regions responsible for the execution of motivated behaviors, e.g.: midbrain, limbic and prefrontal cortex(3). Positive and negative reinforcement mechanisms play a role in the maladaptive pattern of alcohol consumption. As the severity of alcohol use disorder worsens, negative reinforcement mechanisms predominate where negative affective state is relieved by alcohol consumption, thus leading to relapse.

Alcohol’s reinforcing effects are primarily mediated by dopamine, opioid peptides, gamma-aminobutyric-acid, and endocannabinoids(4), while negative reinforcement involves increased recruitment of corticotropin-releasing factor and glutamatergic systems, and down-regulation of gamma-aminobutyric-acid transmission(3, 4).

Screening and Diagnosis of Alcohol Use Disorder

Screening instruments for problematic drinking include the Cut down-Annoyed-Guilty- Eye opener (CAGE) and the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) (Tables 1 and 2)(5, 6). The CAGE is short, may be easily implemented in primary care settings and assesses consequences of drinking. The latter makes it less sensitive as a screening tool for at-risk drinking and gives inconsistent results across different ethnicities(7). The AUDIT actually quantifies alcohol consumption and has been validated across different ethnicities(7). There is a brief version of the AUDIT, developed for use in primary care settings(8).

Table 1.

Cut down-Annoyed-Guilty-Eye opener (CAGE) Questionnaire

| Have you ever felt you should Cut down on your drinking? |

| Have people Annoyed you by criticizing your drinking? |

| Have you ever felt bad or Guilty about your drinking? |

| Have you ever had a drink first thing in the morning to steady your nerves or to get rid of a hangover (Eye opener)? |

Scoring: item responses on the CAGE are scored no (0) or yes (1). A total score of 2 or greater is considered clinically significant.

The CAGE Questionnaire is public domain and no permission is necessary unless used in a profit-making endeavor. The exact wording can be found in the following source reference: Ewing, J.A. Detecting alcoholism: The CAGE questionnaire. JAMA 252, 1905–1907 (1984).(88)

Table 2.

The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT)

| AUDIT Questions: | Scoring system | Your score | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| How often do you have a drink containing alcohol? | Never | Monthly or less | 2 – 4 times per month | 2 – 3 times per week | 4+ times per week | |

| How many drinks containing alcohol do you have on a typical day when you are drinking? | 1 –2 | 3 – 4 | 5 – 6 | 7 – 9 | 10+ | |

| How often have you had 5 or more drinks on one occasion? | Never | Less than monthly | Monthly | Weekly | Daily or almost daily | |

| How often during the last year have you found that you were not able to stop drinking once you had started? | Never | Less than monthly | Monthly | Weekly | Daily or almost daily | |

| How often during the last year have you failed to do what was normally expected of you because of drinking? | Never | Less than monthly | Monthly | Weekly | Daily or almost daily | |

| How often during the last year have you needed a first drink in the morning to get yourself going after a heavy drinking session? | Never | Less than monthly | Monthly | Weekly | Daily or almost daily | |

| How often during the last year have you had a feeling of guilt or remorse after drinking? | Never | Less than monthly | Monthly | Weekly | Daily or almost daily | |

| How often during the last year have you been unable to remember what happened the night before because of your drinking? | Never | Less than monthly | Monthly | Weekly | Daily or almost daily | |

| Have you or somebody else been injured because of your drinking? | No | Yes, but not in the last year | Yes, during the last year | |||

| Has a relative or friend, doctor or other health worker been concerned about your drinking or suggested that you cut down? | No | Yes, but not in the last year | Yes, during the last year | |||

Scoring: 0 – 7 low risk; 8 – 15 increased risk; 16 – 19 high risk; 20+ possible dependence. The AUDIT can detect alcohol problems experienced in the last year. An AUDIT score of ≥ 8 is indicative of harmful or hazardous drinking. Questions 1–8 = 0, 1, 2, 3, or 4 points. Questions 9 and 10 are scored 0, 2, or 4 only.

The AUDIT is reprinted with permission from the World Health Organization. A free AUDIT manual with guidelines for use in primary care settings is available online at www.who.org. To reflect drink serving sizes in the United States (14g of pure alcohol), the number of drinks in question 3 was changed from 6 to 5 and minor language changes were made as in the NIH/NIAAA website: http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/Audit.pdf

The diagnosis of alcohol use disorder, set forth in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), is defined as a problematic pattern of drinking leading to clinically significant impairment and distress for at least 12 months (Table 3)(9). The gold standard to quantify alcohol consumption is the Timeline Followback, a semi-structured interview that is used mostly in research settings(10).

Table 3.

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) 5 criteria for Alcohol Use Disorder

|

| The presence of at least 2 of these symptoms indicates an Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD). |

The severity of the AUD is defined as:

|

| For a comparison of DSM-5 criteria for AUD versus DSM-IV criteria for alcohol abuse or dependence, see NIH/NIAAA website: http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/dsmfactsheet/dsmfact.pdf |

Reprinted with permission from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, (Copyright 2013). American Psychiatric Association.

Objective biomarkers of alcohol use are blood, breath or urine ethanol levels which are highly specific but only reflect very recent use. Ethyl glucuronide, a conjugated ethanol metabolite, is detected in urine several days after drinking and can be used reliably in regular drinkers(11). However, for a single drinking episode, the window of detection depends on the quantity of alcohol consumed.(12, 13) Carbohydrate-deficient transferrin (CDT) is a desialylated isoform of transferrin, increases with chronic heavy alcohol intake and is the most specific marker of alcohol use(14); however its sensitivity is limited, particularly in women, end-stage liver disease and overweight/obese individuals(15). Increased serum liver enzymes, alanine transaminase (ALT), aspartate transaminase (AST) and gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT), are markers of inflammation and oxidative stress, and have low specificity for detecting alcohol use. Moderate drinking may cause elevations in liver enzymes in obese but not normal weight individuals(13); notably, ALT is more sensitive to BMI and GGT to alcohol consumption. Phosphatidylethanol is an abnormal phospholipid generated from phosphatidylcholine in the presence of ethanol and is positive in blood more than 2 weeks after ethanol is cleared from the body(16). It is more sensitive than ethyl glucuronide for identification of current drinking(12) and is more sensitive compared to GGT and CDT(17). A combination of CDT with GGT improves the sensitivity of detecting heavy drinking without loss in specificity(13).

CLINICAL STAGES OF ALCOHOLIC LIVER DISEASE

The risk for alcoholic liver disease rises with increasing daily alcohol consumption with a threshold of 12–22 g/day in women and 24–46 g/day in men(18), however, this relationship is not dose-dependent(19). There are individual differences and risk factors, including genetic predisposition, age, gender, metabolic syndrome, diabetes, obesity, smoking, iron overload, and chronic hepatitis B or C(20, 21) that modify risk.

Alcoholic liver disease comprises several forms ranging from relatively mild and reversible steatosis (fatty liver) and alcoholic hepatitis, to fibrosis and finally cirrhosis and hepatic failure(22). Fatty liver develops in about 90% of individuals who drink >60g/day of alcohol and is generally reversible with 4–6 weeks abstinence(23, 24). About 25% of patients with alcohol use disorder develop alcoholic hepatitis. Treatments for alcoholic hepatitis (e.g.: prednisone and pentoxifylline) may have limited efficacy(25), which further highlights the critical importance of treating the underlying alcohol use disorder(26). The severity of alcoholic hepatitis can range from mild to severe and can be superimposed on chronic liver disease(27). Prospective studies indicate that the recent, rather than lifetime alcohol consumption, predicts alcoholic cirrhosis(19, 28, 29). While treatments for alcoholic liver disease have been extensively reviewed elsewhere(30–34), this review (Box 1) focuses on the treatment of the underlying problem in these patients, i.e. alcohol use disorder.

Box 1. Review Criteria.

In April 2016, we searched PubMed using the following search terms: ‘alcohol use disorder’, ‘liver disease’, ‘alcoholic liver disease’, ‘treatment’. The references from initial papers identified were searched to identify additional references. We focused only on papers written in English.

TREATMENT FOR ALCOHOL USE DISORDER IN PATIENTS WITH ALCOHOLIC LIVER DISEASE

Despite evidence that outcomes improve with integration of psychosocial and medical care(35), there are almost no randomized studies for behavioral and/or pharmacological treatments in patients with alcohol use disorder and alcoholic liver disease. Alcohol abstinence is the most important therapeutic goal for patients with alcoholic liver disease, as abstinence can improve outcome at all stages of disease(36–38).

Psychosocial and behavioral treatments

Brief interventions (Table 4) are a counseling strategy that can be delivered by a health care provider during a 5–10 minute medical office visit. The intervention is aimed at educating the patient about problematic drinking, increasing motivation to change behavior, and reinforcing skills to address problematic drinking(39). In primary care settings, studies support the use of brief interventions to reduce drinking(40, 41) particularly when the intervention is repeated over multiple visits with follow-up telephone consultations(39). Although brief interventions are not sufficient by themselves in those with very heavy use or dependence(42), they can reinforce other therapeutic approaches such as compliance to medications(43) and/or referral to treatment programs(44, 45). This approach is typically referred to with the acronym SBIRT: screening, brief intervention and referral to treatment(26, 46).

Table 4.

Outline of Steps in Brief Intervention

|

Step I. Ask About Alcohol Use

Ask questions regarding alcohol consumption, CAGE questions, AUDIT |

|

Step II. Negotiation and Goal Setting

Is patient willing to focus on drinking; Suggestions for reducing drinking |

|

Step III. Behavioral Modification Techniques

Identify high risk situations; Devise coping strategies |

|

Step IV: Self-Help-Directed Bibliography

Dispense educational materials |

|

Step V. Follow-up and Reinforcement

Drinking log; follow-up appointment and or phone consultation |

Specific psychosocial and behavioral therapies for alcohol use disorder include 12-step facilitation, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and motivational enhancement therapy (MET). Twelve-step facilitation is abstinence-based, and involves participation in Alcoholics Anonymous meetings. The program is grounded in acceptance, spirituality and moral inventories (47). CBT focuses on identifying triggers and maladaptive behaviors that engender relapse. The approach encourages coping mechanisms to allow replacement of alcohol-laden with alcohol-free circumstances(48). MET seeks to frame the decision to stop or modify drinking in terms of a dilemma and helps the patient work through the dilemma by “rolling with the resistance” to change (49). Lastly, mobile phone applications are beginning to be used to support reduction in risky drinking(50).

It is not established if any of these therapies is superior. Indeed, the Matching Alcoholism Treatments to Client Heterogeneity (MATCH) trial(51) showed that they are equivalent. Similarly, the United Kingdom Alcohol Treatment Trial compared social/network therapy to MET and found no difference in outcome(52). The large Combining Medications and Behavioral Interventions (COMBINE) study examined whether combining medications and a behavioral intervention improves drinking outcomes in patients with alcohol use disorder(53). The intervention was a combination of all three interventions used in the MATCH trial. In addition, COMBINE tested Medical Management, an intervention that focuses on medication compliance, management of side-effects and goals toward harmful drinking reduction and/or abstinence(54). The results showed that combination of the behavioral intervention with medications was superior to medication alone and that naltrexone combined with Medical Management can be a cost-effective way to treat alcohol use disorder(53).

Clinical research on the use of psychosocial and behavioral treatments for alcohol use disorder in patients with liver disease is limited. A landmark study integrating treatment for both alcoholic liver disease and alcohol use disorder was conducted by Lieber and colleagues(55). In this study, addition of a brief intervention to a pharmacologic treatment trial for liver fibrosis resulted in a significant reduction in alcohol drinking. Other studies examined behavioral approaches like CBT and MET for alcohol abstinence in patients with alcoholic liver disease and these studies were recently reviewed systematically (13 studies; N = 1,945) by Khan and colleagues(35). While psychosocial interventions alone were not effective in maintaining abstinence, combining comprehensive medical care and behavioral approaches such as CBT and MET did increase abstinence rates. This indicates that the use of integrated care to treat alcohol use disorder in the context of alcoholic liver disease may lead to better outcomes.

Pharmacological treatments: management of alcohol detoxification

Alcohol withdrawal syndrome is characterized by a constellation of acute symptoms, which may include anxiety, tremors, nausea, insomnia, and in severe cases seizures and delirium tremens(56). Delirium tremens may occur at any time during withdrawal, most commonly between 48–72 hours of abstinence. While up to 50% of alcoholic individuals manifest alcohol withdrawal symptoms after stopping drinking, only a small percentage requires medical treatment. The severity of withdrawal is typically measured with ranked scales such as the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol—revised (CIWA-Ar) (Table 5)(57). While CIWA-Ar scores ≥8 but ≤15 indicate a potential need for a pharmacological treatment, an alcohol withdrawal syndrome with a CIWA-Ar score >15 must be treated pharmacologically. Benzodiazepines are the mainstay of treatment as they are the only class of medications that reduces the risk of withdrawal seizures and/or delirium tremens.

Table 5.

Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol—revised (CIWA-Ar) scale

| Nausea/Vomiting - Rate on scale 0 – 7 |

| 0 – None |

| 1 - Mild nausea with no vomiting |

| 2 |

| 3 |

| 4 - Intermittent nausea |

| 5 |

| 6 |

| 7 - Constant nausea and frequent dry heaves and vomiting |

|

|

| Anxiety - Rate on scale 0 – 7 |

| 0 - no anxiety, patient at ease |

| 1 - mildly anxious |

| 2 |

| 3 |

| 4 - moderately anxious or guarded, so anxiety is inferred |

| 5 |

| 6 |

| 7 - equivalent to acute panic states seen in severe delirium or acute schizophrenic reactions. |

|

|

| Paroxysmal Sweats - Rate on Scale 0 – 7. |

| 0 - no sweats |

| 1- barely perceptible sweating, palms moist |

| 2 |

| 3 |

| 4 - beads of sweat obvious on forehead |

| 5 |

| 6 |

| 7 - drenching sweats |

|

|

| Tactile disturbances - Ask, “Have you experienced any itching, pins & needles sensation, burning or numbness, or a feeling of bugs crawling on or under your skin?” |

| 0 – none |

| 1 - very mild itching, pins & needles, burning, or numbness |

| 2 - mild itching, pins & needles, burning, or numbness |

| 3 - moderate itching, pins & needles, burning, or numbness |

| 4 - moderate hallucinations |

| 5 - severe hallucinations |

| 6 - extremely severe hallucinations |

| 7 - continuous hallucinations |

|

|

| Visual disturbances - Ask, “Does the light appear to be too bright? Is its color different than normal? Does it hurt your eyes? Are you seeing anything that disturbs you or that you know isn’t there?” |

| 0 - not present |

| 1 - very mild sensitivity |

| 2 - mild sensitivity |

| 3 - moderate sensitivity |

| 4 - moderate hallucinations |

| 5 - severe hallucinations |

| 6 - extremely severe hallucinations |

| 7 - continuous hallucinations |

|

|

| Tremors - have patient extend arms & spread fingers. Rate on scale 0 – 7. |

| 0 - No tremor |

| 1 - Not visible, but can be felt fingertip to fingertip |

| 2 |

| 3 |

| 4 - Moderate, with patient’s arms extended |

| 5 |

| 6 |

| 7 - severe, even w/ arms not extended |

|

|

| Agitation - Rate on scale 0 – 7 |

| 0 - normal activity |

| 1 - somewhat normal activity |

| 2 |

| 3 |

| 4 - moderately fidgety and restless |

| 5 |

| 6 |

| 7 - paces back and forth, or constantly thrashes about |

|

|

| Orientation and clouding of sensorium - Ask, “What day is this? Where are you? Who am I?” Rate scale 0 – 4 |

| 0 – Oriented |

| 1 – cannot do serial additions or is uncertain about date |

| 2 - disoriented to date by no more than 2 calendar days |

| 3 - disoriented to date by more than 2 calendar days |

| 4 - Disoriented to place and / or person |

|

|

| Auditory Disturbances - Ask, “Are you more aware of sounds around you? Are they harsh? Do they startle you? Do you hear anything that disturbs you or that you know isn’t there?” |

| 0 - not present |

| 1 - Very mild harshness or ability to startle |

| 2 - mild harshness or ability to startle |

| 3 - moderate harshness or ability to startle |

| 4 - moderate hallucinations |

| 5 - severe hallucinations |

| 6 - extremely severe hallucinations |

| 7 - continuous hallucinations |

|

|

| Headache - Ask, “Does your head feel different than usual? Does it feel like there is a band around your head?” Do not rate dizziness or lightheadedness. |

| 0 - not present |

| 1 - very mild |

| 2 – mild |

| 3 – moderate |

| 4 - moderately severe |

| 5 – severe |

| 6 - very severe |

| 7 - extremely severe |

The CIWA-Ar is not copyrighted and may be used freely. Source: Sullivan, J.T., Sykora, K., Schneiderman, J., Naranjo, C.A. & Sellers, E.M. Assessment of alcohol withdrawal: the revised clinical institute withdrawal assessment for alcohol scale (CIWA-Ar). Br J Addict 84:1353–1357 (1989).(57)

In alcoholic patients with alcoholic liver disease, lorazepam or oxazepam are preferred as they do not undergo phase I biotransformation, rather, undergo only glucuronidation which is preserved even if liver function is compromised. Benzodiazepines may be administered on a fixed or symptom-triggered schedule. In patients with alcohol use disorder and liver disease, a symptom-triggered schedule (i.e. only when symptoms exceed a threshold of severity) is preferred, with assessment at least every 4 hours or more frequently if withdrawal symptoms are present. This strategy requires close and expert monitoring to ensure appropriate medication is provided and is preferable as it avoids unnecessary dosing of sedative hypnotic medication. Finally, it is important to distinguish withdrawal symptoms from those of alcohol intoxication or hepatic encephalopathy as benzodiazepines should not be administered in the latter cases. Other factors to consider are supportive care including fluid and electrolyte balance. Caution is needed in preventing the precipitation of Wernicke’s encephalopathy, especially in those patients with end-stage liver disease who present with encephalopathy. Since prolonged glucose supplementation without the addition of thiamine can be a risk factor for the development of Wernicke’s encephalopathy, thiamine supplementation should be given promptly(58).

Pharmacological treatments to promote abstinence and prevent relapse

Consistent with the increasing knowledge of the neurobiology of addictions(3, 4), medications have been developed (Table 6)(59). In the US, acamprosate, disulfiram and naltrexone (oral and intramuscular) are approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment of alcohol use disorder. A recent meta-analysis supports the efficacy of naltrexone and acamprosate, but not disulfiram, for alcohol use disorder(60). Efforts have also been made to test other pharmacotherapies as potential new treatments for alcohol use disorder. These medications are FDA-approved for other indications, some of them have shown efficacy for alcohol use disorder in Phase 2/3 trials, but are not FDA-approved for alcohol use disorder. Among them, the most promising are baclofen, gabapentin, ondansetron, topiramate and varenicline(59).

Table 6.

FDA-approved medications and others tested in alcohol use disorder patients

| FDA-approved Medications for alcohol use disorder | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Dosage | Pharmacological target | Possible use in alcohol use disorder patients with alcoholic liver disease? | |

| Acamprosate | 666 mg TID | Possibly NMDA receptor agonist | Yes (no hepatic metabolism) |

| Disulfiram | 250–500 mg QD | Inhibition of Acetaldehyde dehydrogenase | No (hepatic metabolism; cases of liver toxicity have been reported) |

| Naltrexone*

PO or IM |

PO: 50 mg QD IM: 380 mg monthly |

Mu opiate receptor antagonist | With caution (perceptions of liver toxicity limit use in advanced alcoholic liver disease) |

| Not FDA-approved Medications tested for alcohol use disorder | |||

| Baclofen | 10 mg TID; 80 mg QD max | GABAB receptor agonist | Yes (minimal hepatic metabolism) Baclofen has been formally tested in clinical studies with alcohol use disorder patients with liver cirrhosis |

| Gabapentin | 900–1800 mg QD | Unclear-modulates GABA transmission | Yes (no hepatic metabolism) |

| Ondansetron | 1–16 mcg/kg BID | 5HT3 antagonist | Yes, but with caution because liver toxicity has been reported, albeit relationship to ondansetron administration is not determined |

| Topiramate | 300 mg QD | Anticonvulsant multiple targets: -Glutamate/+GABA | Yes (partial hepatic metabolism mostly by glucoronidation). In patients with hepatic encephalopathy, use with caution: topiramate-related cognitive side-effects may confound the clinical course and treatment of hepatic encephalopathy |

| Varenicline | 2 mg QD | Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist | Yes (minimal hepatic metabolism) |

Nalmefene is not-FDA approved but was recently approved in Europe for alcohol use disorder. Compared to naltrexone, nalmefene has a longer half-life and no evidence of hepatotoxicity.

FDA: Food and Drug Administration; TID: three times a day; NMDA: N-methyl-D-aspartate; QD: once a day; PO: per os (oral); IM: intramuscular; GABA: gamma-aminobutyric acid; BID: twice a day; HT: serotonin

There is, however, a lack of formal clinical trials that have tested the role of pharmacotherapies in patients with alcohol use disorder and alcoholic liver disease (26). Although hepatotoxicity with naltrexone is rare(61), naltrexone could induce liver injury and is contraindicated in patients with liver diseases as specified in an FDA ‘‘black box”(26). Acamprosate has not formally been tested either in patients with alcoholic liver disease, however it is the preferable FDA-approved medication in this population as it does not undergo hepatic metabolism; there are no reports of hepatotoxicity.

Baclofen, gabapentin, ondansetron, topiramate and varenicline have no evidence of liver toxicity, therefore they might also be useful in patients with alcohol use disorder and alcoholic liver disease (see Table 6 for details). However, only baclofen has been formally tested in patients with alcohol use disorder and clinically significant alcoholic liver disease in a randomized controlled trial (62, 63) and in observational studies(64, 65); as such, although further research with baclofen is needed, its potential utility for treatment of alcohol use disorder in hepatology settings has been highlighted(66, 67). Unexplored are the combinations of pharmacotherapies and behavioral treatments and of different medications in patients with alcohol use disorder and alcoholic liver disease.

Liver Transplantation

Liver transplantation represents a life-saving treatment for patients with end-stage liver disease. Patients with alcohol use disorder must demonstrate 6 months’ abstinence to be placed on a liver transplant waiting list. Relapse to drinking results in removal from the list with the requirement to demonstrate another 6 months’ abstinence for relisting, a timeframe that is often incompatible with the prognosis of these patients. While 6 months abstinence is commonly required, few transplant programs include treatment programs for alcohol use disorder(68). One-year relapse rates range from 67 to 81%(69) in patients with alcoholic liver disease therefore, effective, ongoing rehabilitation for alcohol addiction is necessary to achieve sustained abstinence(70). Of note, liver transplantation without the 6-month abstinence requirement has been used to treat patients with severe, acute alcoholic hepatitis who fail to respond to steroid therapy(71, 72). Liver transplantation in this population results in long-term survival benefits with recidivism to drinking at rates comparable or below those liver transplant patients who were required to have 6 months abstinence. For an extensive review on the management of alcohol use disorder in patients requiring liver transplant, see(68).

SHIFTING CLINICAL LANDSCAPE: COMORBIDITIES IN PATIENTS WITH ALCOHOL USE DISORDER AND ALCOHOLIC LIVER DISEASE

There is a shifting clinical landscape of alcoholic liver disease which includes a younger age at presentation and increasing comorbid obesity(73). By contrast, with the emergence of efficacious direct acting antiviral (DAA) drugs for Hepatitis C (HCV)(74), the comorbid etiology of alcohol use disorder and HCV will diminish in importance. Alcohol can be a singular etiology of liver disease or can be one of several etiologies, as is the case for example, with comorbid viral hepatitis and/or obesity-related non-alcoholic steatohepatitis.

Comorbidity of HCV and alcohol confers a poorer prognosis (20). HCV is the most common blood borne pathogen in the US with an estimated 2.7 million persons living with chronic HCV infection(75). The prevalence of HCV is 3- to 30-fold higher in alcoholic individuals compared with the general population(76). Alcoholism represents an independent risk factor for HCV infection(77, 78). Concomitant alcohol use accelerates HCV disease progression. While the threshold level of drinking responsible for this progression is not well-established(20), the two conditions have a synergistic effect(79). As a consequence, there are no safe levels of alcohol consumption in HCV-infected individuals, therefore alcohol abstinence is necessary for optimal treatment of HCV infection, especially in this new era of effective treatments for HCV.

Alcohol-induced symptoms of depression, anxiety, and insomnia are common and often indistinguishable from a primary psychiatric disorder(80). However, these abate with abstinence, usually within a month, though there is a protracted abstinence syndrome that can persist for months(81). Treatment for these symptoms is sometimes required. This may be particularly challenging in those patients with alcohol use disorder and HCV infection who are taking DAAs, which are substrates as well as inhibitors of cytochrome P450 3A4 and P-glycoprotein. There are clinically important drug-drug interactions between these drugs and common medications used to treat withdrawal (e.g., alprazolam; midazolam), sleep problems (e.g., zolpidem; trazodone), and psychiatric symptoms (e.g., escitalopram; St John’s Wort; carbamazepine)(82).

Finally, obesity increases risk for all stages of alcoholic liver disease(83). Prospective cohort studies show that alcohol use disorder and obesity exert a greater than additive effect on development of liver disease and share a common pathophysiology(84). Treating alcohol use disorder in obese patients with liver disease and obesity will be integral to the management of these patients. As HCV decreases in importance as an etiology for liver disease(85), alcohol use disorder and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis will be the most common etiologies for end-stage liver disease. As such, patients with alcohol use disorder will be prominent among those seen in hepatology practices.

CONCLUSIONS

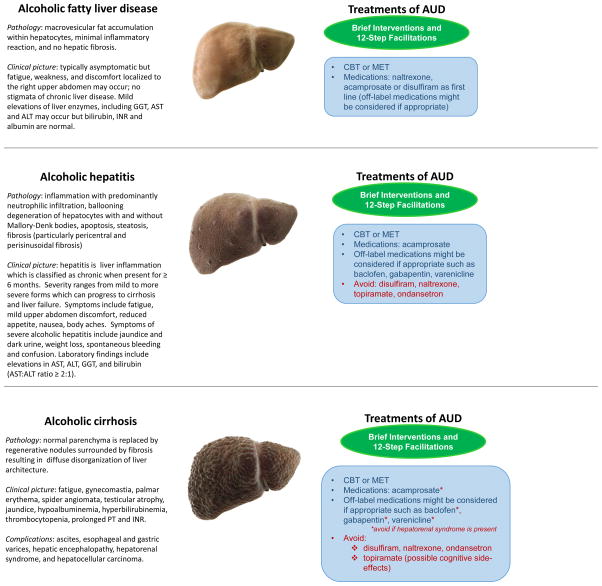

Alcohol abstinence represents the cornerstone in the treatment of alcoholic liver disease. The clinical literature summarized here indicates that treatments for patients with alcoholic liver disease exist and providing these treatments is critical. To this end, it is important to educate physicians in addiction medicine (86). The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism has developed several professional education materials for health care providers(87). Figure 1 outlines multimodal treatments based on the severity of alcoholic liver disease.

Figure 1.

Outline of the different stages of alcoholic liver disease and possible treatments, behavioral and pharmacologic, for alcohol use disorder in patients with alcoholic liver disease. The figure outlines the different and/or complementary options that clinicians may consider when treating alcohol use disorder at each stage of alcoholic liver disease. Multidisciplinary approaches may include behavioral and/or pharmacological interventions. While brief medical and psychosocial interventions (in green) may suffice in helping some patients quit alcohol drinking, more complex and comprehensive treatments (behavioral and pharmacological; in blue) may be needed as the severity of alcohol use disorder worsens and becomes critical with increasing severity of alcoholic liver disease. The figure also highlights the pharmacological interventions that should be avoided in advanced alcoholic liver disease.

Abbreviations: ALT: Alanine aminotransferase; AST: Aspartate aminotransferase; AUD: Alcohol use disorder; CBT: Cognitive Behavioral Therapies; GGT: Gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase; INR: International normalized ratio; MET: Motivational Enhancement Therapy; PT: Prothrombin time

Photo Credit: Science Picture Co / Science Source

These treatment approaches for alcohol use disorder help patients, including those with alcoholic liver disease, reduce alcohol consumption, achieve abstinence and prevent relapse. Integration of addiction medicine into the multidisciplinary teams that care for these patients may improve outcomes.

Clinical Significance.

Alcohol use disorder is a leading cause of mortality and morbidity

Alcohol is a leading cause of liver disease; indeed, new effective treatments for HCV make even more critical to address alcohol use disorder

Psychosocial, behavioral and/or pharmacologic treatments may help patients with alcohol use disorder to achieve abstinence

There is a critical need to expand the use of these treatment tools in general medicine and hepatology clinical settings

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank: Lisa Farinelli, Section on Clinical Psychoneuroendocrinology and Neuropsychopharmacology, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) and National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), for providing support with the preparation of the manuscript; Melinda Moyer and Fred Donodeo, Communications and Public Liaison Branch, NIAAA, for technical assistance with the preparation of the figure; Dr. David Kleiner, Laboratory of Pathology, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, for providing comments on the figure; and Karen Smith, National Institutes of Health (NIH) Library, for bibliographic assistance. The work was supported by NIH intramural funding ZIA-AA000218 (Section on Clinical Psychoneuroendocrinology and Neuropsychopharmacology; PI: Leggio), jointly supported by NIAAA and NIDA.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Both authors contributed equally to all aspects of this manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Nutt DJ, King LA, Phillips LD Independent Scientific Committee on Drugs. Drug harms in the UK: a multicriteria decision analysis. Lancet. 2010;376(9752):1558–65. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61462-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. Rockville, MD: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Volkow ND, Koob GF, McLellan AT. Neurobiologic Advances from the Brain Disease Model of Addiction. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(4):363–71. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1511480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koob GF, Le Moal M. Addiction and the brain antireward system. Annu Rev Psychol. 2008;59:29–53. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soderstrom CA, Smith GS, Kufera JA, Dischinger PC, Hebel JR, McDuff DR, et al. The accuracy of the CAGE, the Brief Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test, and the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test in screening trauma center patients for alcoholism. J Trauma. 1997;43(6):962–9. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199712000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Girela E, Villanueva E, Hernandez-Cueto C, Luna JD. Comparison of the CAGE questionnaire versus some biochemical markers in the diagnosis of alcoholism. Alcohol Alcohol. 1994;29(3):337–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maisto SA, Saitz R. Alcohol use disorders: screening and diagnosis. Am J Addict. 2003;12(Suppl 1):S12–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2003.tb00493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Connor JP, Haber PS, Hall WD. Alcohol use disorders. Lancet. 2016;387(10022):988–98. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00122-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, (DSM-5) 5. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Connors GJ, Agrawal S. Assessing drinking outcomes in alcohol treatment efficacy studies: selecting a yardstick of success. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27(10):1661–6. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000091227.26627.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Allen JP, Wurst FM, Thon N, Litten RZ. Assessing the drinking status of liver transplant patients with alcoholic liver disease. Liver Transpl. 2013;19(4):369–76. doi: 10.1002/lt.23596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Helander A, Peter O, Zheng Y. Monitoring of the alcohol biomarkers PEth, CDT and EtG/EtS in an outpatient treatment setting. Alcohol Alcohol. 2012;47(5):552–7. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/ags065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Niemela O, Alatalo P. Biomarkers of alcohol consumption and related liver disease. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2010;70(5):305–12. doi: 10.3109/00365513.2010.486442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anton RF. Carbohydrate-deficient transferrin for detection and monitoring of sustained heavy drinking. What have we learned? Where do we go from here? Alcohol. 2001;25(3):185–8. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(01)00165-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fagan KJ, Irvine KM, McWhinney BC, Fletcher LM, Horsfall LU, Johnson L, et al. Diagnostic sensitivity of carbohydrate deficient transferrin in heavy drinkers. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014;14:97. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-14-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nanau RM, Neuman MG. Biomolecules and Biomarkers Used in Diagnosis of Alcohol Drinking and in Monitoring Therapeutic Interventions. Biomolecules. 2015;5(3):1339–85. doi: 10.3390/biom5031339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hartmann S, Aradottir S, Graf M, Wiesbeck G, Lesch O, Ramskogler K, et al. Phosphatidylethanol as a sensitive and specific biomarker: comparison with gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, mean corpuscular volume and carbohydrate-deficient transferrin. Addict Biol. 2007;12(1):81–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2006.00040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Becker U, Deis A, Sorensen TI, Gronbaek M, Borch-Johnsen K, Muller CF, et al. Prediction of risk of liver disease by alcohol intake, sex, and age: a prospective population study. Hepatology. 1996;23(5):1025–9. doi: 10.1002/hep.510230513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kamper-Jorgensen M, Gronbaek M, Tolstrup J, Becker U. Alcohol and cirrhosis: dose--response or threshold effect? J Hepatol. 2004;41(1):25–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hutchinson SJ, Bird SM, Goldberg DJ. Influence of alcohol on the progression of hepatitis C virus infection: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3(11):1150–9. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(05)00407-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Addolorato G, Mirijello A, Leggio L, Ferrulli A, Landolfi R. Management of alcohol dependence in patients with liver disease. CNS Drugs. 2013;27(4):287–99. doi: 10.1007/s40263-013-0043-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kasper DL, Braunwald E, Fauci AS, Hauser SL, Llongo DL, Jameson JL. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine. 16. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crabb DW. Pathogenesis of alcoholic liver disease: newer mechanisms of injury. Keio J Med. 1999;48(4):184–8. doi: 10.2302/kjm.48.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lieber CS, Jones DP, Decarli LM. Effects of Prolonged Ethanol Intake: Production of Fatty Liver Despite Adequate Diets. J Clin Invest. 1965;44:1009–21. doi: 10.1172/JCI105200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thursz MR, Richardson P, Allison M, Austin A, Bowers M, Day CP, et al. Prednisolone or pentoxifylline for alcoholic hepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(17):1619–28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1412278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Addolorato G, Mirijello A, Barrio P, Gual A. Treatment of alcohol use disorders in patients with alcoholic liver disease. J Hepatol. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ishak KG, Zimmerman HJ, Ray MB. Alcoholic liver disease: pathologic, pathogenetic and clinical aspects. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1991;15(1):45–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1991.tb00518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Askgaard G, Gronbaek M, Kjaer MS, Tjonneland A, Tolstrup JS. Alcohol drinking pattern and risk of alcoholic liver cirrhosis: a prospective cohort study. J Hepatol. 2015;62(5):1061–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sorensen TI, Orholm M, Bentsen KD, Hoybye G, Eghoje K, Christoffersen P. Prospective evaluation of alcohol abuse and alcoholic liver injury in men as predictors of development of cirrhosis. Lancet. 1984;2(8397):241–4. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)90295-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Altamirano J, Bataller R. Alcoholic liver disease: pathogenesis and new targets for therapy. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;8(9):491–501. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2011.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Day CP. Treatment of alcoholic liver disease. Liver Transpl. 2007;13(11 Suppl 2):S69–75. doi: 10.1002/lt.21336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lucey MR. Management of alcoholic liver disease. Clin Liver Dis. 2009;13(2):267–75. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mathurin P, Louvet A, Dharancy S. Treatment of severe forms of alcoholic hepatitis: where are we going? J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23(Suppl 1):S60–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.05286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O'Shea RS, Dasarathy S, McCullough AJ. Alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 2010;51(1):307–28. doi: 10.1002/hep.23258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khan A, Tansel A, White DL, Kayani WT, Bano S, Lindsay J, et al. Efficacy of Psychosocial Interventions in Inducing and Maintaining Alcohol Abstinence in Patients With Chronic Liver Disease: A Systematic Review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14(2):191–202. e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.07.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Borowsky SA, Strome S, Lott E. Continued heavy drinking and survival in alcoholic cirrhotics. Gastroenterology. 1981;80(6):1405–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brunt PW, Kew MC, Scheuer PJ, Sherlock S. Studies in alcoholic liver disease in Britain. I. Clinical and pathological patterns related to natural history. Gut. 1974;15(1):52–8. doi: 10.1136/gut.15.1.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Luca A, Garcia-Pagan JC, Bosch J, Feu F, Caballeria J, Groszmann RJ, et al. Effects of ethanol consumption on hepatic hemodynamics in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 1997;112(4):1284–9. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70142-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fleming MF, Manwell LB, Barry KL, Adams W, Stauffacher EA. Brief physician advice for alcohol problems in older adults: a randomized community-based trial. J Fam Pract. 1999;48(5):378–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bertholet N, Daeppen JB, Wietlisbach V, Fleming M, Burnand B. Reduction of alcohol consumption by brief alcohol intervention in primary care: systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(9):986–95. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.9.986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O'Donnell A, Anderson P, Newbury-Birch D, Schulte B, Schmidt C, Reimer J, et al. The impact of brief alcohol interventions in primary healthcare: a systematic review of reviews. Alcohol Alcohol. 2014;49(1):66–78. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agt170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saitz R. Alcohol screening and brief intervention in primary care: Absence of evidence for efficacy in people with dependence or very heavy drinking. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2010;29(6):631–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2010.00217.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.O'Connor PG, Farren CK, Rounsaville BJ, O'Malley SS. A preliminary investigation of the management of alcohol dependence with naltrexone by primary care providers. Am J Med. 1997;103(6):477–82. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(97)00271-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bernstein E, Bernstein J, Levenson S. Project ASSERT: an ED-based intervention to increase access to primary care, preventive services, and the substance abuse treatment system. Ann Emerg Med. 1997;30(2):181–9. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(97)70140-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moos RH, Moos BS. Long-term influence of duration and frequency of participation in alcoholics anonymous on individuals with alcohol use disorders. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72(1):81–90. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Strobbe S. Prevention and screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment for substance use in primary care. Prim Care. 2014;41(2):185–213. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Longabaugh R, Wirtz PW, Zweben A, Stout RL. Network support for drinking, Alcoholics Anonymous and long-term matching effects. Addiction. 1998;93(9):1313–33. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.93913133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Larimer ME, Palmer RS, Marlatt GA. Relapse prevention. An overview of Marlatt's cognitive-behavioral model. Alcohol Res Health. 1999;23(2):151–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miller WR, Benefield RG, Tonigan JS. Enhancing motivation for change in problem drinking: a controlled comparison of two therapist styles. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1993;61(3):455–61. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gustafson DH, McTavish FM, Chih MY, Atwood AK, Johnson RA, Boyle MG, et al. A smartphone application to support recovery from alcoholism: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(5):566–72. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.4642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Carroll KM, Connors GJ, Cooney NL, DiClemente CC, Donovan DM, Kadden RR, et al. Internal validity of Project MATCH treatments: discriminability and integrity. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;66(2):290–303. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.2.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Copello A, Orfor J, Hodgson R, Tober G, Barrett C Trial URTUKAT. Social behaviour and network therapy basic principles and early experiences. Addict Behav. 2002;27(3):345–66. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00176-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Anton RF, O'Malley SS, Ciraulo DA, Cisler RA, Couper D, Donovan DM, et al. Combined pharmacotherapies and behavioral interventions for alcohol dependence: the COMBINE study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295(17):2003–17. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.17.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pettinati HM, Weiss RD, Dundon W, Miller WR, Donovan D, Ernst DB, et al. A structured approach to medical management: A psychosocial intervention to support pharmacotherapy in the treatment of alcohol dependence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005:170–8. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2005.s15.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lieber CS, Weiss DG, Groszmann R, Paronetto F, Schenker S. II. Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study of polyenylphosphatidylcholine in alcoholic liver disease. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27(11):1765–72. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000093743.03049.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Swift RM. Drug therapy for alcohol dependence. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(19):1482–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199905133401907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sullivan JT, Sykora K, Schneiderman J, Naranjo CA, Sellers EM. Assessment of alcohol withdrawal: the revised clinical institute withdrawal assessment for alcohol scale (CIWA-Ar) Br J Addict. 1989;84(11):1353–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1989.tb00737.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schabelman E, Kuo D. Glucose before thiamine for Wernicke encephalopathy: a literature review. J Emerg Med. 2012;42(4):488–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2011.05.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Edwards S, Kenna GA, Swift RM, Leggio L. Current and promising pharmacotherapies, and novel research target areas in the treatment of alcohol dependence: a review. Curr Pharm Des. 2011;17(14):1323–32. doi: 10.2174/138161211796150765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jonas DE, Amick HR, Feltner C, Bobashev G, Thomas K, Wines R, et al. Pharmacotherapy for Adults With Alcohol-Use Disorders in Outpatient Settings. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tetrault JM, Tate JP, McGinnis KA, Goulet JL, Sullivan LE, Bryant K, et al. Hepatic safety and antiretroviral effectiveness in HIV-infected patients receiving naltrexone. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2012;36(2):318–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01601.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Addolorato G, Leggio L, Ferrulli A, Cardone S, Vonghia L, Mirijello A, et al. Effectiveness and safety of baclofen for maintenance of alcohol abstinence in alcohol-dependent patients with liver cirrhosis: randomised, double-blind controlled study. Lancet. 2007;370(9603):1915–22. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61814-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Leggio L, Ferrulli A, Zambon A, Caputo F, Kenna GA, Swift RM, et al. Baclofen promotes alcohol abstinence in alcohol dependent cirrhotic patients with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. Addict Behav. 2012;37(4):561–4. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Heydtmann M. Baclofen effect related to liver damage. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35(5):848. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yamini D, Lee SH, Avanesyan A, Walter M, Runyon B. Utilization of Baclofen in Maintenance of Alcohol Abstinence in Patients with Alcohol Dependence and Alcoholic Hepatitis with or without Cirrhosis. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2014;49(4):453–6. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agu028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Runyon BA, Aasld Introduction to the revised American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases Practice Guideline management of adult patients with ascites due to cirrhosis 2012. Hepatology. 2013;57(4):1651–3. doi: 10.1002/hep.26359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.European Association for the Study of L. EASL clinical practical guidelines: management of alcoholic liver disease. J Hepatol. 2012;57(2):399–420. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lee MR, Leggio L. Management of Alcohol Use Disorder in Patients Requiring Liver Transplant. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(12):1182–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15040567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Miller WR, Walters ST, Bennett ME. How effective is alcoholism treatment in the United States? J Stud Alcohol. 2001;62(2):211–20. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lucey MR. Liver transplantation for alcoholic liver disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;11(5):300–7. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2013.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mathurin P, Moreno C, Samuel D, Dumortier J, Salleron J, Durand F, et al. Early liver transplantation for severe alcoholic hepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(19):1790–800. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Im GY, Kim-Schluger L, Shenoy A, Schubert E, Goel A, Friedman SL, et al. Early Liver Transplantation for Severe Alcoholic Hepatitis in the United States-A Single-Center Experience. Am J Transplant. 2016;16(3):841–9. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Diehl AM. Obesity and alcoholic liver disease. Alcohol. 2004;34(1):81–7. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2004.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zoulim F, Liang TJ, Gerbes AL, Aghemo A, Deuffic-Burban S, Dusheiko G, et al. Hepatitis C virus treatment in the real world: optimising treatment and access to therapies. Gut. 2015;64(11):1824–33. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Denniston MM, Jiles RB, Drobeniuc J, Klevens RM, Ward JW, McQuillan GM, et al. Chronic hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003 to 2010. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(5):293–300. doi: 10.7326/M13-1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Singal AK, Anand BS. Mechanisms of synergy between alcohol and hepatitis C virus. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41(8):761–72. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3180381584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Quan CM, Krajden M, Grigoriew GA, Salit IE. Hepatitis C virus infection in patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17(1):117–9. doi: 10.1093/clinids/17.1.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rosman AS, Waraich A, Galvin K, Casiano J, Paronetto F, Lieber CS. Alcoholism is associated with hepatitis C but not hepatitis B in an urban population. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91(3):498–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Poynard T, Bedossa P, Opolon P. Natural history of liver fibrosis progression in patients with chronic hepatitis C. The OBSVIRC, METAVIR, CLINIVIR, and DOSVIRC groups. Lancet. 1997;349(9055):825–32. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)07642-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wittchen HU, Jacobi F, Rehm J, Gustavsson A, Svensson M, Jonsson B, et al. The size and burden of mental disorders and other disorders of the brain in Europe 2010. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;21(9):655–79. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2011.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Schuckit MA. Comorbidity between substance use disorders and psychiatric conditions. Addiction. 2006;101:76–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Burger D, Back D, Buggisch P, Buti M, Craxi A, Foster G, et al. Clinical management of drug-drug interactions in HCV therapy: challenges and solutions. J Hepatol. 2013;58(4):792–800. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Raynard B, Balian A, Fallik D, Capron F, Bedossa P, Chaput JC, et al. Risk factors of fibrosis in alcohol-induced liver disease. Hepatology. 2002;35(3):635–8. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.31782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hart CL, Morrison DS, Batty GD, Mitchell RJ, Davey Smith G. Effect of body mass index and alcohol consumption on liver disease: analysis of data from two prospective cohort studies. BMJ. 2010;340:c1240. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chhatwal J, Chen Q, Kanwal F. Why We Should Be Willing to Pay for Hepatitis C Treatment. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wood E, Samet JH, Volkow ND. Physician education in addiction medicine. JAMA. 2013;310(16):1673–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.280377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. [on May 2, 2016];2016 Accessed at National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism at http://www.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/clinical-guides-and-manuals.

- 88.Ewing JA. Detecting alcoholism. The CAGE questionnaire. JAMA. 1984;252(14):1905–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.252.14.1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]