Abstract

Study Objectives:

To determine if patients with childhood onsets (CO) of both major depression and insomnia disorder show blunted depression and insomnia treatment responses to concurrent interventions for both disorders compared to those with adult onsets (AO) of both conditions.

Methods:

This study was a secondary analysis of data obtained from a multisite randomized clinical trial designed to test the efficacy of combining a psychological/behavior insomnia therapy with antidepressant medication to enhance depression treatment outcomes in patients with comorbid major depression and insomnia. This study included 27 adults with CO of depression and insomnia and 77 adults with AO of both conditions. They underwent a 16-week treatment including: (1) a standardized two-step pharmacotherapy for depression algorithm, consisting of escitalopram, sertraline, and desvenlafaxine in a prescribed sequence; and (2) either cognitive behavioral insomnia therapy (CBT-I) or a quasi-desensitization control (CTRL) therapy. Main outcome measures were the 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD-17) and the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) completed pre-treatment and every 2 weeks thereafter.

Results:

The AO and CO groups did not differ significantly in regard to their pre-treatment HRSD-17 and ISI scores. Mixed model analyses that adjusted for the number of insomnia treatment sessions attended showed that the AO group achieved significantly lower, subclinical scores on the HRSD-17 and ISI than did the CO group by the time of study exit. Moreover, a significant group by treatment arm interaction suggested that HRSD-17 scores at study exit remained significantly higher in the CO group receiving the CTRL therapy than was the case for the participants in the CO group receiving CBT-I. Greater proportions of the AO group achieved a priori criteria for remission of insomnia (49.3% vs. 29.2%, p = 0.04) and depression (45.5% vs. 29.6%, p = 0.07) than did those in the CO group.

Conclusions:

Patients with comorbid depression and insomnia who experienced the first onset of both disorders in childhood are less responsive to the treatments offered herein than are those with adult onsets of these comorbid disorders. Further research is needed to identify therapies that enhance the depression and insomnia treatment responses of those with childhood onsets of these two conditions.

Citation:

Edinger JD, Manber R, Buysse DJ, Krystal AD, Thase ME, Gehrman P, Fairholme CP, Luther J, Wisniewski S. Are patients with childhood onset of insomnia and depression more difficult to treat than are those with adult onsets of these disorders? A report from the TRIAD study. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13(2):205–213.

Keywords: major depression, insomnia disorder, childhood and adult onset, CBT-I

INTRODUCTION

Patients who present with concurrent major depressive disorder (MDD) and chronic insomnia represent a particularly challenging group to manage. Insomnia often is not merely a symptom of the co-occurring MDD but rather represents a comorbid disorder that can significantly complicate depression management. Among MDD patients, those who have poor sleep tend to have more severe depressive illness and a greater propensity for suicidal ideation than those without insomnia symptoms.1–3 In fact, poor sleep, defined subjectively and objectively (by polysomnography [PSG]), is associated with poorer depression outcomes, including longer time to remission, lower rates of remission, and greater treatment attrition rates.4–6 Moreover, a substantial proportion of MDD patients continue to experience insomnia even if their MDD is otherwise adequately treated, and the continuation of this form of sleep disturbance enhances their risk for eventual depression relapse.7–11 Thus, when insomnia occurs comorbid to MDD it often requires separate treatment attention.

BRIEF SUMMARY

Current Knowledge/Study Rationale: Patients with comorbid insomnia and major depression benefit by interventions that simultaneously provide targeted therapies for each of these conditions, yet not all such patients receiving this treatment combination benefit equally from it. The current study was conducted to determine if age of onset of insomnia and depression moderate eventual treatment outcomes when these conditions occur comorbidly.

Study Impact: The study showed that patients with childhood onsets of insomnia and depression show less insomnia and depression improvement with treatment consisting of antidepressant medication and cognitive-behavioral insomnia therapy than do those with adult onsets of both conditions. Results imply that patients with childhood onsets of depression and insomnia may represent a difficult to treat group with treatment needs that go unmet by standard CBT-I/ antidepressant medication protocols.

Although limited in number, some previous studies have suggested that targeted therapies for insomnia provide MDD patients some benefit toward improvement in their depressive syndromes. For example, a small pilot study conducted by our group12 showed that patients with comorbid MDD and insomnia who were provided a treatment consisting of cognitive behavioral insomnia therapy (CBT-I) and the antidepressant, escitalopram, showed a higher depression remission rate than similar patients provided the antidepressant and a sham insomnia therapy (61.5% vs. 33.3%). In a larger multi-site trial13 that enrolled 545 patients with MDD and insomnia, patients who received fluoxetine for depression combined with eszopiclone for insomnia showed a significantly higher depression remission rate than did those who received antidepressant medication and a placebo medication for insomnia (42% vs. 33%). Yet it is noteworthy that our recently completed multisite trial14 did not show significantly higher remission rates among patients receiving CBT-I combined with antidepressant medication than among those who received antidepressant medications combined with sham insomnia therapy. These recent negative findings as well as the results of prior studies with positive results suggest a substantial proportion of patients with MDD and insomnia fail to achieve depression remission even when provided concurrent treatments for both disorders. This observation, in turn, suggests the need to identify moderators of treatment response that help identify patients who have a more treatment-refractory depression and may require more intensive or alternate forms of intervention.

Of course, an important first step in identifying these less responsive patients entails determining those characteristics that may place these patients at risk for a blunted treatment response. In this regard, there is some literature suggesting that the age of onset of both depression and insomnia can be important predictors of disease course and eventual treatment response. For example, the literature focused on MDD has shown that both a positive family history and early depression onset predict greater chronicity of the depressive illness as well as worse response to treatment, including lower rates of depression remission.15–18 Likewise, the insomnia literature has described a childhood onset or “idiopathic” insomnia that emerges during early childhood years, waxing and waning throughout adulthood and remaining relatively unresponsive to conventional interventions.19–21 Such observations would lead to the speculation that when both MDD and insomnia have their onsets at an early age, the affected patient is likely to be particularly disposed to chronic and treatment-resistant courses for these two comorbid conditions. Unfortunately, studies have yet to be conducted to test this possibility.

The current study was conducted using data collected from a larger randomized clinical trial14 designed to test a combined depression and insomnia treatment for improving depression treatment outcomes in patients with both disorders. The purpose of the current study was to compare the treatment outcomes of patients who had histories of childhood onsets of both their depression and insomnia against the outcomes shown by patients who reported adult onsets of both conditions. Based on the current literature and our own clinical observations, we hypothesized that patients who reported childhood onsets of both depression and insomnia would show less overall improvement in their depression and insomnia symptoms and would be less likely to achieve depression and insomnia remission in response to combined depression and insomnia treatment than would those who had adult onsets of these comorbid conditions.

METHODS

Design

The current study entailed a secondary analysis of data collected from the parent, multi-site Treatment of Insomnia And Depression (TRIAD) Study14 conducted to determine the efficacy of combined cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) and antidepressant medication for improving depression treatment outcomes among patients with comorbid major depressive and insomnia disorders. The parent study comprised a 3-site randomized clinical trial in which participants were randomized to a combined CBT-I + antidepressant medication or a quasi-desensitization sham control insomnia therapy (CTRL) + antidepressant medication at the collaborating study sites (Stanford University; University of Pittsburgh; Duke University). Study protocols were identical at each of the 3 sites, and data were collected centrally by the Data Coordinating Center (DCC) at University of Pittsburgh. The parent study protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional review boards at each study site, and data and safety monitoring progress reports were reviewed twice per year by an external Data and Safety Monitoring Board whose membership was approved by the funding agency, the National Institute of Mental Health. Data for the current report were taken from a subset of the total study sample who had either childhood onset (i.e., before age 21) of both depression and insomnia or adult onset (age 21 or older) of both disorders.

Participants

Those enrolled in the larger parent study were English-speaking individuals between 18 and 75 years of age who: met the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IVTR)22 criteria for MDD (assessed by a trained interviewer using the Structured Clinical Interview for Psychiatric Disorders – SCID23); scored ≥ 16 on the 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD)24 and ≥ 11 on the Insomnia Severity Index25; and had habitual bedtimes between 20:00 and 03:00 and habitual rise times between 04:00 and 11:00. They also met DSM-IV-TR22 criteria for primary insomnia assessed by the Duke Structured Interview for Sleep Disorders (DSISD)26,27 except for the criterion that excludes insomnia occurring exclusively during the course of another mental disorder. As this latter exclusion is no longer included in the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5)28 criteria for an insomnia diagnosis, it can be surmised that study enrollees would have met current DSM-5 criteria for Insomnia Disorder. Finally, those included in the current study were those who had had their first onset of both major depression and insomnia prior to age 21 (i.e., the childhood onset group) as well as those who had had their first onsets of both disorders after age 21 (adult onset group). The age of 21 was used to define adulthood since this was the age recommended by the National Institutes of Health for defining adulthood at the time this study was initiated.

Excluded from the current sample were those parent study enrollees who had their first onset of one disorder, depression or insomnia, prior to age 21 and their first onset of the other disorder after reaching 21 years of age. These individuals were excluded so that we could compare the treatment outcomes of individuals with onset of both depression and insomnia occurring during childhood and adulthood. Other exclusion criteria used in selecting participants for the parent study and thus the current sample consisted of: (1) Current suicidal potential, psychotic features, or having received electroconvulsive therapy or vagal nerve stimulation treatment during the last year; (2) inability/unwillingness to discontinue current psychotropic medications, including hypnotic medications and antidepressants, for at least 14 days prior to study screening; (3) past non-responsiveness to all 3 antidepressant medications used in this trial; (4) unstable or life-threatening medical conditions; (5) those with at least moderate (AHI ≥ 15) sleep-disordered breathing or milder sleep-disordered breathing (10 < AHI < 15) associated with excessive daytime sleepiness (Epworth score > 10), since our clinical experience suggests such patients require specific treatment (e.g., continuous positive airway pressure) for their sleep apnea; however, those with AHI ≥ 5 and < 10 were allowed to enroll since our clinical experience has suggested that such cases with insomnia benefit by CBT-I, (6) other primary sleep disorders including restless legs syndrome experienced more than once a week, periodic limb movement disorder defined as a PLM-arousal index > 15 on qualifying PSG, any parasomnia more than once a week, and any circa-dian rhythm disorder; (7) current diagnoses of schizophrenia or other psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder, dementia, or related cognitive disorders; (8) diagnoses of posttraumatic stress disorder, anorexia or bulimia nervosa, or obsessive compulsive disorder that necessitates clinical management that is not part of the study treatment algorithm; (9) current diagnoses of Alcohol-Related Disorders, Caffeine-Related Disorder and other Substance-Related Dependency Disorders; (10) testing positive for illicit substances on the urine drug screen; (11) an Axis II diagnosis of antisocial, schizotypal or severe borderline personality disorder; (12) recent engagement (< 4 months) in psychotherapy for depression or prior CBT-I exposure; and (13) women who are pregnant or breast-feeding.

A final sample of 104 study participants met selection criteria for both the parent study and the current secondary analyses. Of these, 27 participants had experienced their first onset of both depression and insomnia prior to reaching 21 years of age and 77 had had their first onset of both depression and insomnia after reaching age 21. The demographic and clinical characteristics of these groups, hereafter called the childhood onset (CO) and adult onset (AO) groups, as well as the entire study sample are provided in Table 1.

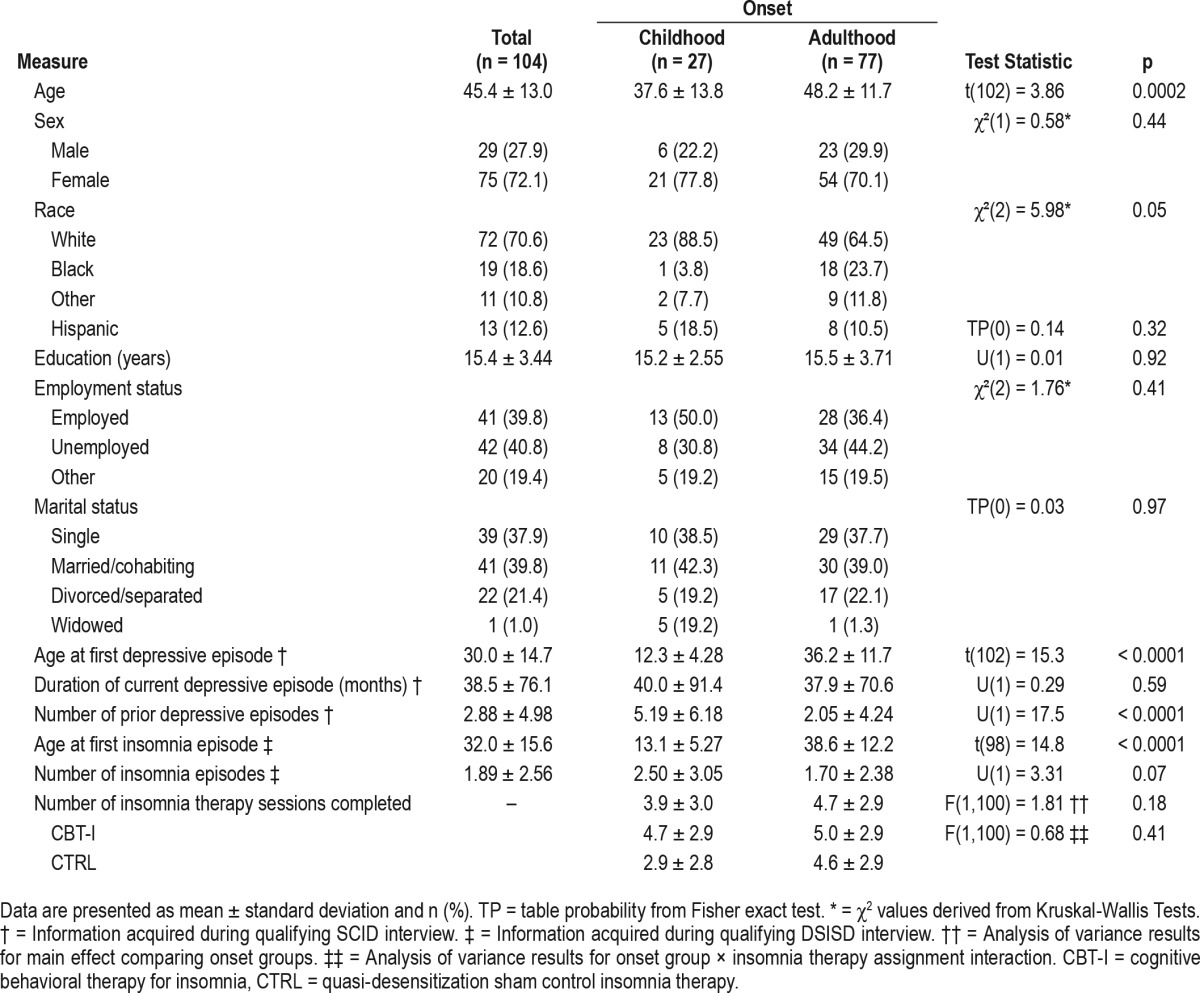

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical measures by onset of depression and insomnia.

Measures

Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression

The 17-item version of the Hamilton Rating Scale24 for Depression (HRSD-17) was administered prior to treatment and then biweekly during a 16-week treatment period to assess changes/ improvements in depression symptoms resulting from treatment. The HRSD-17 is a semi-structured interview that was administered by independent raters masked to treatment assignment. Study raters were all certified by having their ratings of two taped interviews fall within 2 points of the score assigned to the interviews by an expert rater. As its name implies the HRSD-17 containing 17 items and each item is scored on a 3- or 5-point scale, depending on the item. Scores can range from 0 to 54. Scores between 0 and 7 indicate a normal person with regard to depression, scores between 8 and 17 indicate mild depression, scores between 18 and 24 indicate moderate depression, and scores > 24 indicate severe depression.

Insomnia Severity Index (ISI)25,29

This 7-item self-report instrument was administered to participants prior to treatment and then biweekly during a 16-week treatment period to assess changes/improvements in insomnia symptoms resulting from treatment. The ISI provides a global measure of perceived insomnia severity based on several indicators (e.g., difficulty falling or staying asleep, satisfaction with sleep, degree of daytime impairment). The total score ranges from 0–28 with each 7-point score range indicating increasing insomnia severity: 0–7 (no clinical insomnia), 8–14 (sub threshold insomnia), 15–21 (insomnia of moderate severity), and 22–28 (severe insomnia). Consistent with prior research,30 an ISI score < 8 at study exit was used in this study to connote insomnia remission.

Depression Remission Assessment

The depression module of the SCID was administered to participants at the same time points the HSDR-17 was completed. Remission was defined following American College of Neuropsychopharmacology recommendations (ACNP)31 by presence of the following 2 conditions for at least 3 consecutive weeks: (a) absence of both depressed mood and anhedonia; and (b) no more than 2 other DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criterion symptoms of depression. Remission status was determined from the final two depression modules of the SCID completed by each participant over the 16-week treatment phase of the study. We chose to assess remission during the final portion of active treatment rather than during an additional post-treatment period to avoid added participant burden arising from additional post-treatment assessment procedures.

Procedure

As required by their participation in the parent study, participants included in this investigation first underwent a screening process composed of: (1) an initial telephone screening to determine general eligibility for the study; (2) completion of a sleep diary; (3) the SCID23 to diagnose current Major Depressive Episode and rule out other Axis I disorders according to DSM-IV-TR criteria; (4) a SCID-II Patient Questionnaire (MHS Inc., 1998) followed by a clinical interview using the SCID-II if indicated; (5) the DSISD26,27 to confirm an insomnia diagnosis and rule out other sleep disorders; and (6) a medical history and review of systems.

Participants meeting selection criteria first completed pre-treatment baseline HRSD-17 and ISI. They then were randomized to the study's treatment conditions comprised of pharmacotherapy for depression combined with either CBT-I or a CTRL psychological treatment for insomnia. During the 16-week treatment phase, participants met every other week with their respective study site's psychiatrist to initiate and subsequently manage the pharmacotherapy for depression. During each visit, the study psychiatrist assessed antidepressant response and tolerability, using the Clinician Global Impressions scale (CGI).32 Concurrent to their ongoing pharmacotherapy, participants also had 7 visits (weeks 1–4, 6, 8, and 12) with their assigned psychotherapist who provided a course of CBT-I or the CTRL intervention. The HRSD-17 and ISI were completed biweekly during the treatment phase and during the 2-week period immediately after the completion of treatment. For the purpose of the current study, the HRSD-17 and ISI scores participants achieved by the end of their treatment participation as well as their statuses vis-avis the depression remission criteria were considered for our analyses.

Treatments

Pharmacotherapy (Medication Algorithm)

The pharmacotherapy followed principles used in the STAR*D study,33 allowing structured flexibly in the choice of the first medication to be tried, and one switch to another medication. Specific medications utilized included two SSRIs, escitalopram (ESC) and sertraline (SERT), and the SNRI desvenlafaxine succinate (DVS). The pharmacotherapy algorithm consisted of 2 phases, each lasting 8 weeks. The first medication used was selected based on the following rules: If there was no history of ESC failure, the first medication was ESC. Otherwise, if there was no history of SERT failure, the first medication was SERT; and if there was history of SERT failure in the past but no history of venlafaxine or DVS failure, then the first medication was DVS. At week 8, the patient was evaluated for a potential switch to another medication. If the patient had a CGI score ≥ 3 for the last two consecutive visits, indicating non-response, a switch from ESC to SERT or from SERT to DVS was recommended. If the patient is already on DVS, the dose could be increased. To minimize study attrition, the patient was moved to the next level of the algorithm if at any time intolerance to the current medication was noted, regardless of treatment week (ESC to SERT or SERT to DVS). Medication management visits occurred at baseline and biweekly thereafter. The study psychiatrists who administered pharmacotherapy to study participants were kept blind to the assigned psychotherapy they concurrently received.

Psychotherapy for Insomnia

The psychotherapy for insomnia consisted of seven 45-minute individual sessions of CBT-I or CTRL. Both psychotherapies focused exclusively on insomnia and avoided discussions of issues unrelated to sleep. When a participant spontaneously raised non-sleep issues, the therapist gently redirected the patient to the prescribed content of the session. The only exception allowed was when the clinical presentation necessitated an immediate intervention, such as when the participant expressed suicidal thoughts. If suicidal ideation was noted a thorough risk assessment was conducted by the treating therapist and reviewed by the study site PI. If risk was deemed minimal (passive ideation with no plan or intent) the participant was monitored daily by phone and allowed to continue in the study if the ideation resolved. If suicidal ideation seemed serious and clinical judgement suggested there existed significant risk for self-harm, the participant was removed from the trial and referred to immediate care including hospitalization if deemed necessary. Psychotherapists were naïve to both of the study treatments prior to participation and were randomized and trained to deliver the therapy to which they were assigned. Competency of therapists was determined based on audio recording of work samples conducted by two of the authors (JE for CTRL and RM for CBT-I). Therapists were not informed about study hypotheses and about the fact that one of the insomnia therapies was actually a sham intervention. Therapists had group supervision calls with therapists delivering the same treatment and a supervisor (authors RM for CBT-I and JE for CTRL), initially weekly and later (approximately 2 years after study start date) every other week.

Those assigned to the active insomnia therapy were given a course of individual CBT-I during their 7 visits with their assigned psychotherapist. This treatment included: (a) education about normal sleep, sleep in depression, circadian rhythms, and basic sleep hygiene information about the use of substances, sleep environment, and timing of eating and exercising (Session 1); (b) sleep restriction,34 with initial time in bed equal to average total sleep time plus 30 minutes35,36 and stimulus control instructions37 (Session 2); (c) strategies for reducing cognitive and somatic arousals related to sleep, including relaxation training (Session 3); (d) cognitive restructuring,38 which was provided throughout the intervention, focused on sleep, and avoided cognitive therapy for depression; and (e) relapse prevention, including encouragement to use the skills acquired after therapy ended (Session 7).

Those receiving the CTRL psychotherapy for insomnia were provided a quasi-desensitization procedure39 that has been successfully used as control therapy in previous insomnia outcome studies.12,40 This intervention did not include any of the active components of CBT-I, except sleep education and sleep hygiene information. In particular, recommendations about sleep restriction, altering sleep-related cognitions, or stimulus control instructions were not provided. Instead this intervention consisted of the creation of a 12-item hierarchy of sleep-related distressing situations occurring while in bed at night, and having the participant visualize a pairing of each of these situations with emotionally neutral images. This treatment mimics the therapy process in traditional systematic desensitization used for treating phobias, but its previous applications12,40 suggest that this specific treatment format has minimal effect on insomnia.

Study Analyses

Baseline characteristics of the CO and AO groups were compared using t-tests and χ2 tests. Primary analyses were carried out on the intent-to-treat sample. Secondary analyses were conducted on a modified sample of 102 participants, excluding 2 participants who were deemed ineligible after randomization (one developed psychotic symptoms before starting study treatments and another developed bipolar disorder around week 4). Mixed-effects linear models with autoregressive error structure were used to examine the relative differences between onset groups with respect to the final HRSD-17 and ISI scores obtained. These models included a random slope and fixed effects for onset group (CO vs. AO), treatment, and their interaction; mixed effect models use all data points available for each participant. Mixed model logistic regression analyses were also conducted to test the effects of onset group, treatment, and their interaction on the probability of meeting the depression remission criteria and an insomnia remission status defined by and ISI score < 8 at time of exit from treatment. In both sets of mixed model analyses, the number of insomnia treatment sessions attended by participants was used as a covariate. In all cases results obtained with the intent-to-treat sample and the sample that excluded the two ineligible participants produced comparable statistical results so only the results for the intent-to-treat sample are presented herein.

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

Baseline characteristics for the CO and AO groups and for the sample as a whole are presented in Table 1. Also included in Table 1 are the results of the statistical comparisons of the two study groups in regard to these characteristics. These data show that the CO group was significantly younger and more likely to be Caucasian than was the AO group. Also as might be expected, the CO group had significantly more prior bouts of depression and had their first depressive and insomnia episodes at a significantly younger age than did the AO group. Although data in Table 1 suggest that the CO group assigned to the CTRL insomnia therapy completed the fewest insomnia therapy sessions, statistical analyses showed no main effects for onset group membership (F1,100 = 1.81, p = 0.18) or insomnia therapy type (F1,100 = 3.57, p = 0.06), or for the onset group × insomnia therapy type interaction (F1,100 = 0.68, p = 0.41). Moreover, the two onset groups did not differ significantly in regard to the remainder of the demographic and clinical characteristics listed in Table 1.

Depression and Insomnia Treatments

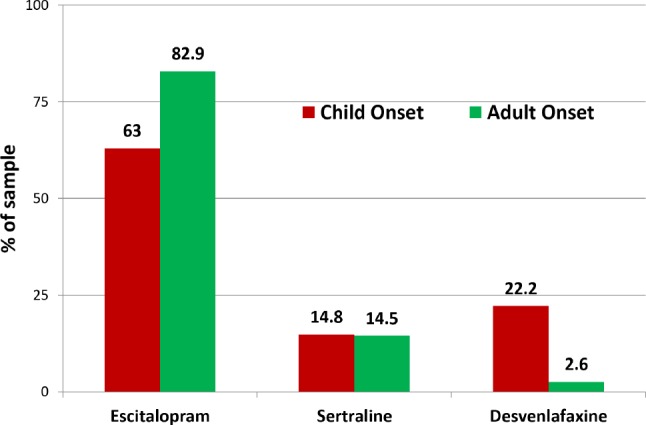

Application of the antidepressant medication algorithm resulted in significantly different patterns of starting medication assignments for the CO and AO groups (χ2(2) = 10.9; p = 0.004). Figure 1 shows the proportions of the CO and AO groups given ESC, SERT, and DVS as their starting medication upon entry into the treatment phase. A smaller proportion of the CO group were provided the first medication choice, ESC, as their starting medication than were those in the AO group, and a larger proportion were provided the third drug choice, DVS, as their starting medication in the trial than were the AO patients. This finding would suggest participants comprising the CO group were more likely to have histories of unresponsiveness to the first 2 medication choices in the medication algorithm than were those in the AO group.

Figure 1. Proportion of CO and AO patients assigned to each study medication as their initial depression therapy.

Proportions of AO and CO participants assigned to each study medication as their starting medication as determined by the medication algorithm. Use of this algorithm resulted a lower proportion of the CO group being assigned to Escitalopram and a higher proportion assigned to Desvenlafaxine as their starting medication resulting in an overall χ2(2) = 10.9; p = 0.004 in the comparison of medication assignments. CO = childhood onset, AO = adult onset.

There was no significant difference in the proportion of CO and AO patients assigned to each of the 2 insomnia therapies (χ2(1) = 0.19; p = 0.66). Fifteen CO and 39 AO patients were assigned to CBT-I, and 12 CO and 38 AO patients were assigned to the CTRL insomnia therapy.

Mixed Model Analyses of HRSD-17 and ISI Scores

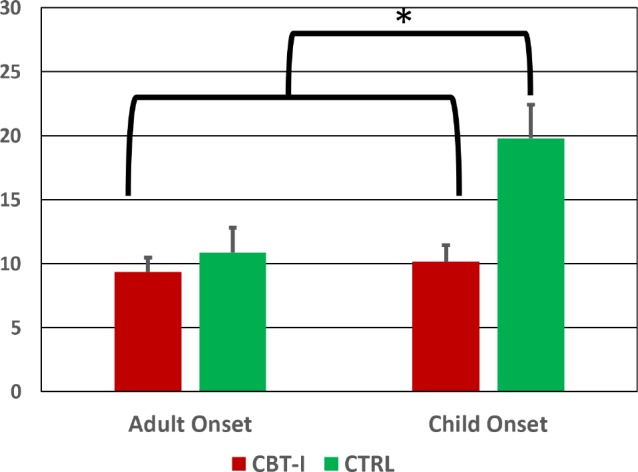

Preliminary statistical comparisons showed the CO and AO groups did not differ (p values > 0.80) in regard to their pre-treatment mean HRSD-17 (CO = 21.2 ± 4.1; AO = 21.4 ± 3.3). Mixed model analysis of the HRSD-17 scores showed a signifi-cant main effect for onset group via the Wald chi square (W) statistic (W (1) = 10.40; p = 0.0013) which translates into a medium effect size for this group difference Cohen's d = 0.52). However, results also showed a significant onset group by treatment arm interaction (W (1) = 5.13; p = 0.023). Figure 2 shows the mean HSRD-17 scores at study exit of the 4 cells depicting this interaction. The AO and CO groups assigned to CBT-I as well as the AO group assigned to the CTRL therapy had mean HSRD-17 scores at study exit that did not differ significantly from each other; whereas pairwise comparisons (Tukey-Kramer tests) showed the CO group assigned to the CTRL insomnia therapy had significantly higher mean HSRD-17 scores at study exit than did the remaining 3 groups (all p values < 0.0021).

Figure 2. HRSD-17 scores at study exit for the CO and AO groups receiving CBT-I and CTRL insomnia therapies.

Mean HSRD-17 scores at study exit for the AO and CO groups within each treatment arm. A posteriori comparisons showed the CO group assigned to the CTRL therapy had significantly higher HRSD-17 scores at study exit indicated greater residual depression than did the other three subgroups (all ps < 0.0021). CO = childhood onset, AO = adult onset, CBT-I = cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia, CTRL = quasi-desensitization sham control insomnia therapy.

Pre-treatment comparisons of our CO and AO groups showed no differences between these groups on the ISI scores at study entry (CO = 18.7 ± 3.9; AO = 18.5 ± 4.2). Mixed model analysis of ISI scores showed a significant main effect for onset group (W (1) = 6.34; p = 0.012; Cohen's d = 0.58). ISI scores at study exit were 5.66 points (95%CI = 1.25 to 10.07) higher in the CO group than in the AO on average. Neither the main effect for treatment arm nor the onset group by treatment arm interaction were significant (ps > 0.20).

Depression and Insomnia Remission Status at Post-Treatment Assessment

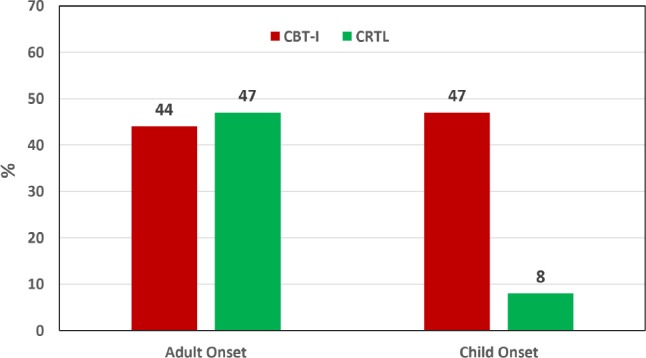

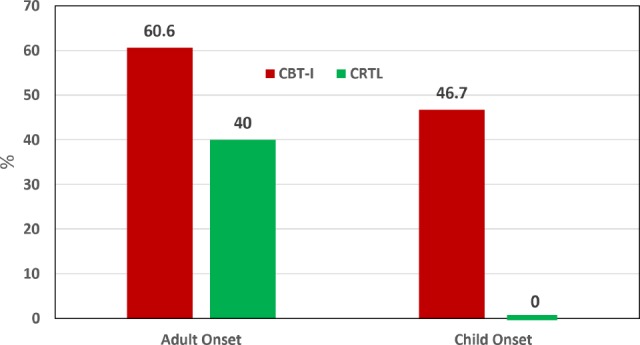

Figure 3 shows the proportions of individuals within onset groups and treatment arms who met the ACNP criteria for depression remission at the post-treatment assessment. Although a lower proportion of the CO group in general, and particularly those assigned to the CTRL insomnia therapy, met remission criteria, the mixed model logistic analyses of depression remission showed only small effect (Cramer's V = −0.14) resulting in only a trend toward a main effect for the onset group comparison (p < 0.07). Likewise, there was a small and nonsignificant effect noted for onset group by treatment arm interaction (p < 0.085).

Figure 3. Depression remission rates for the CO and AO groups in each treatment arm.

Comparison of depression remission rates as defined by the ACNP31 criteria applied to the study exit SCID interview findings. Despite the trends noted in this figure the mixed model logistic analyses showed no significant effects of onset group, treatment arm or the onset × treatment arm interaction. CO = childhood onset, AO = adult onset, CBT-I = cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia, CTRL = quasi-desensitization sham control insomnia therapy.

Figure 4 shows the proportions of individuals within onset groups and treatment arms who met insomnia remission status by achieving an ISI score < 8 by study exit. A lower proportion of the CO group in general, and particularly those assigned to the CTRL insomnia therapy, met the insomnia remission criteria. Statistical analysis showed only a small (Cramer's V = −0.178) significant main effect for onset group with 49.3% of the AO group and only 29.2% of the CO group achieving insomnia remission (p = 0.038). The main effect for treatment arm and the onset group × treatment arm interaction were not significant (p values > 0.11).

Figure 4. Insomnia remission rates for the CO and AO groups in each treatment arm.

A mixed model logistic analysis showed a small (Cramer's V = −0.178) significant main effect for onset group with the AO group showing a greater propensity to achieve insomnia remission than the CO group (p = 0.038). The main effect for treatment arm and the onset group × treatment arm interaction were not significant (p values > 0.11). CO = childhood onset, AO = adult onset, CBT-I = cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia, CTRL = quasi-desensitization sham control insomnia therapy.

DISCUSSION

The current study aimed to determine if the age of first onsets of MDD and insomnia disorder in patients who suffer from both conditions was associated with poor depression and insomnia treatment response in patients concurrently provided depression- and insomnia-targeted interventions. We specifically predicted that patients with CO of both disorders would be more treatment-refractory and show a blunted treatment response in comparison to a group who reported AO of both conditions. Likely as a function of the levels of clinically significant depression and insomnia required for study entry, our CO and AO groups did not differ significantly in regard to their baseline HRSD-17 and ISI scores. However, analyses of HRSD-17 and ISI scores at post treatment were generally consistent with our predictions in that the AO group reported significantly less depression and insomnia severity on these outcome measures than did our CO group. However, we also noted that CO participants who received CBT-I had post-treatment HRSD-17 scores similar to those obtained by the AO group as a whole, whereas CO participants given the CTRL therapy had much worse HRSD-17 scores upon their study exit than did the remainder of the sample. Thus, providing an efficacious insomnia-targeted therapy along with an antidepressant medication seems particularly important to depression treatment outcomes of those with CO of both depression and insomnia.

The CO group in general and particularly participants assigned to the CTRL insomnia therapy had the lowest depression and insomnia remission rates, but only the AO vs. CO group difference in insomnia remission rate was statistically significant. However, as noted above, the effect size for this finding was in the “small” range. Considering the modest total sample size and the relatively limited number of participants falling in the CO group, we may have had limited power for detecting significant group differences in the depression remission rates observed. Nonetheless, it is interesting that CO group assigned to the CTRL therapy which included sleep hygiene instructions showed a much lower insomnia remission rate than did the AO group who received this CTRL intervention. It is not clear why this difference was observed but it could be that that CO are much more likely to have heard the sleep hygiene advice prior to their study entry and thus were less responsive to such insomnia intervention.

In addition to the predicted differences noted in our main outcome measures, comparisons of our CO and AO groups on sociodemographic and clinical features upon treatment initiation seem to further buttress our notion that CO patients represent a particularly challenging group to manage. Participants in the CO group were younger yet reported more than twice as many prior depressive episodes than did the AO group at the time of their study entry. Furthermore, participants in the CO group had a much greater likelihood of being started on the third medication choice than was the case for the AO group. This finding suggests that a sizable proportion of these individuals had previously failed trials of the two SSRI medications that are most commonly used for depression management.

Why those with CO of both depression and insomnia are relatively unresponsive to combined targeted therapies for their conditions remains open to speculation. It may be that the occurrence of both conditions early in life before maturing into adulthood hampers the development of coping skills and resiliency needed to manage life stressors effectively without suffering significantly from their emotional impacts. It also may be that persons with CO of these conditions represent a distinctive disease group possibly with specific genetic loading for chronic and more severe forms of depression and insomnia that ultimately may require alternate, more intensive and/ or early-life interventions to improve their overall depression and insomnia treatment outcomes. Of course it also could be the case that the poorer treatment response of the CO group may have occurred merely since they suffered from depression and insomnia for a much longer period of time than did the AO group. Future longitudinal studies conducted over years rather than months that include proper genetic probes would be needed to explore these various possibilities.

In considering our findings, a number of study limitations should be noted. First, as mentioned above, our sample of CO participants was relatively small so replication with larger samples is needed before clinically relevant conclusions can be drawn. Also, not all patients considered in our comparisons actually received our active insomnia therapy, CBT-I as some were assigned to the CTRL therapy. Comparisons of larger groups of CO and AO cohorts who receive comparable active treatments for depression and insomnia would therefore be useful to ascertain whether these initial findings would be replicated. Finally, this study included only a psychological/behavioral insomnia therapy combined with antidepressant and therefore its results cannot be generalized to treatments consisting of antidepressant medications combined with other insomnia therapies or other combinations of concomitant therapies for both disorders. For example, it is possible that different results would have been obtained if all participants had received an evidence-based pharmacotherapy for insomnia in combination with the depression medication algorithm used. Nonetheless our findings seem noteworthy particularly in regard to the observed group differences in depression and insomnia symptom improvement rates shown by the two subgroups. Additional trials with larger samples assigned to active insomnia therapies including available pharmacotherapies for insomnia seem warranted.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. This research was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health Grant #s MH078924, MH078961, and MH079256. Dr. Edinger has received research support from Philips Respironics, Inc. and Merck. Dr. Manber has received an unrestricted gift from Phillips Respironics, is on the advisory board of General Sleep, and has received non-monetary donations from Wyeth Pharmaceutical and Forest Laboratories. Dr. Buysse has served as a paid consultant for Philips Respironics, Cereve, Merck, Eisai, Otsuka, and Emmi Solutions. He has also served as faculty on CME programs produced by CME Outfitters and Medscape. Dr. Krystal has received grant support from NIH, Teva, Sunovion, Astellas, Abbott, Neosync, Brainsay, Janssen, ANS St. Jude, and Novartis. He is a consultant to Abbott, AstraZeneca, Attentiv, Teva, Eisai, Jazz, Janssen, Merck, Paladin, Pernix, Neurocrine, Otsuka, Lundbeck, Roche, Somnus, Sunovion, Somaxon, Takeda, and Transcept. Dr. Thase has been an advisor/ consultant to Alkermes, Allergan, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cerecor, Inc., Eli Lilly, Fabre-Kramer Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Forest Laboratories, Gerson Lehrman Group, GlaxoSmithKline, Guidepoint Global, H. Lundbeck A/S, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, MedAvante, Merck, Moksha8, Mylan, Naurex, Inc., Neuronetics, Inc., Novartis, Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceuticals, Otsuka, Pamlab/Nestle, Pfizer, Roche, Shire, Sunovion, Takeda, Teva, Trius Therapeutical, Inc., as well as the US Food and Drug Administration and the National Institute of Mental Health. Dr. Thase has received honoraria for international continuing education talks supported by AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Merck, and Pfizer. He has received research grants from Alkermes, AssureRx, AstraZeneca, Avanir, Eli Lilly, Forest, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Otsuka, and Roche, as well as from the National Institute of Mental Health and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. He reports equity holdings in MedAvante, Inc and receives royalties from American Psychiatric Foundation, Guilford Publiations, Herald House and WW Norton & Company, Inc. Dr. Gehrman has received grant support from Merck and he is a consultant to both Johnson & Johnson and to the General Sleep Corporation. Dr. Wisniewski and Dr. Luther have a research grant with Janseen Research and Development. Dr. Fairholme has indicated no financial conflicts of interest. The study performance sites were Stanford University, University of Pittsburgh, and Duke University. The funding agency did not have any role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Institute of Mental Health, National Jewish Health, Duke University Medical Center, Stanford University, the University of Pittsburgh, the University of Pennsylvania, University of Idaho or the Department of Veterans Affairs. Results from this study were presented at the Sleep 2014 Annual Meeting in June, 2014, in Baltimore, MD.

ABBREVIATIONS

- ACPN

American College of Neuropsychopharmacology

- AHI

apnea-hypopnea index

- AO

adult onsets

- CBT-I

cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia

- CGI

Clinician Global Impressions scale

- CO

childhood onsets

- CTRL

quasi-desensitization sham control insomnia therapy

- DCC

data coordinating center

- DSISD

Duke Structured Interview for Sleep Disorders

- DSM

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

- DVS

desvenlafaxine

- ESC

escitalopram

- HRSD-17

17-item version of the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression

- ISI

Insomnia Severity Index

- MDD

major depressive disorder

- PI

principal investigator

- PSG

polysomnography

- PLM

periodic limb movements

- SERT

sertraline

- SCID

Structured Clinical Interview for Psychiatric Disorders

- SNRI

selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor

- SSRIs

selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

- STAR*D

Sequenced Treatment Alternative to Relieve Depression Study

- TRAID

Treatment of Insomnia and Depression Study

REFERENCES

- 1.Sunderajan P, Gaynes BN, Wisniewski SR, et al. Insomnia in patients with depression: a STAR*D report. CNS Spectr. 2010;15(6):394–404. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900029266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ribeiro JD, Pease JL, Gutierrez PM, et al. Sleep problems outperform depression and hopelessness as cross-sectional and longitudinal predictors of suicidal ideation and behavior in young adults in the military. J Affect Disord. 2012;136(3):743–750. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.09.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thase ME. Depression, sleep, and antidepressants. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl 4):55–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Houck PR, et al. Does lorazepam impair the antidepressant response to nortriptyline and psychotherapy? J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58(10):426–432. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v58n1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dew MA, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Houck PR, et al. Temporal profiles of the course of depression during treatment. Predictors of pathways toward recovery in the elderly. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54(11):1016–1024. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830230050007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thase ME, Buysse DJ, Frank E, et al. Which depressed patients will respond to interpersonal psychotherapy? The role of abnormal EEG sleep profiles. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(4):502–509. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.4.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carney CE, Segal ZV, Edinger JD, Krystal AD. A comparison of rates of residual insomnia symptoms following pharmacotherapy or cognitive-behavioral therapy for major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(2):254–260. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reynolds CF, 3rd, Frank E, Houck PR, et al. Which elderly patients with remitted depression remain well with continued interpersonal psychotherapy after discontinuation of antidepressant medication? Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(7):958–962. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.7.958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee E, Cho HJ, Olmstead R, Levin MJ, Oxman MN, Irwin MR. Persistent sleep disturbance: a risk factor for recurrent depression in community-dwelling older adults. Sleep. 2013;36(11):1685–1691. doi: 10.5665/sleep.3128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nierenberg AA, Husain MM, Trivedi MH, et al. Residual symptoms after remission of major depressive disorder with citalopram and risk of relapse: a STAR*D report. Psychol Med. 2010;40(1):41–50. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709006011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nierenberg AA, Keefe BR, Leslie VC, et al. Residual symptoms in depressed patients who respond acutely to fluoxetine. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(4):221–225. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v60n0403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Manber R, Edinger JD, Gress JL, San Pedro-Salcedo MG, Kuo TF, Kalista T. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia enhances depression outcome in patients with comorbid major depressive disorder and insomnia. Sleep. 2008;31(4):489–495. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.4.489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fava M, McCall WV, Krystal A, et al. Eszopiclone co-administered with fluoxetine in patients with insomnia coexisting with major depressive disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59(11):1052–1060. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manber R, Buysse DJ, Edinger J, et al. Efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia combined with antidepressant pharmacotherapy in patients with comorbid depression and insomnia: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(10):e1316–e1323. doi: 10.4088/JCP.15m10244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Akiskal HS, King D, Rosenthal TL, Robinson D, Scott-Strauss A. Chronic depressions. Part 1. Clinical and familial characteristics in 137 probands. J Affect Disord. 1981;3(3):297–315. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(81)90031-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hollon SD, Shelton RC, Wisniewski S, et al. Presenting characteristics of depressed outpatients as a function of recurrence: preliminary findings from the STAR*D clinical trial. J Psychiatr Res. 2006;40(1):59–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jang S, Jung S, Pae C, Kimberly BP, Craig-Nelson J, Patkar AA. Predictors of relapse in patients with major depressive disorder in a 52-week, fixed dose, double blind, randomized trial of selegiline transdermal system (STS) J Affect Disord. 2013;151(3):854–859. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vittengl JR, Clark LA, Thase ME, Jarrett RB. Predictors of longitudinal outcomes after unstable response to acute-phase cognitive therapy for major depressive disorder. Psychotherapy. 2015;52(2):268–277. doi: 10.1037/pst0000021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hauri P, Olmstead E. Childhood-onset insomnia. Sleep. 1980;3(1):59–65. doi: 10.1093/sleep/3.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Regestein QR, Reich P. Incapacitating childhood-onset insomnia. Compr Psychiatry. 1983;24(3):244–248. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(83)90075-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thorpy MJ. Diagnostic Classification Steering Committee. International Classification of Sleep Disorders: Diagnostic and Coding Manual. Rochester, MN: American Sleep Disorders Association; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. text revision. [Google Scholar]

- 23.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Non-patient Edition. New York, NY: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hamilton M. Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. Br J Soc Clin Psychol. 1967;6(4):278–296. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1967.tb00530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bastien CH, Vallières A, Morin CM. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med. 2001;2(4):297–307. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(00)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Edinger J, Kirby A, Lineberger M, Loiselle M, Wohlgemuth W, Means M. The Duke Structured Interview for Sleep Disorders. Durham, NC: Duke University Medical Center; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carney CE, Edinger JD, Olsen MK, Stechuchak KM, Krystal AD, Wyatt JK. Inter-rater reliability for insomnia diagnoses derived from the Duke Structured Interview for Sleep Disorders. Sleep. 2008;31:A250. Abstract Suppl. [Google Scholar]

- 28.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morin CM, Belleville G, Belanger L, Ivers H. The Insomnia Severity Index: psychometric indicators to detect insomnia cases and evaluate treatment response. Sleep. 2011;34(5):601–608. doi: 10.1093/sleep/34.5.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morin C, Vallières A, Guay B, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy, singly and combined with medication, for persistent insomnia: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;301(19):2005–2015. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rush AJ, Kraemer HC, Sackeim HA, et al. Report by the ACNP Task Force on response and remission in major depressive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31(9):1841–1853. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hedges DW, Brown BL, Shwalb DA. A direct comparison of effect sizes from the clinical global impression-improvement scale to effect sizes from other rating scales in controlled trials of adult social anxiety disorder. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2009;24(1):35–40. doi: 10.1002/hup.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, et al. Evaluation of outcomes with citalopram for depression using measurement-based care in STAR*D: implications for clinical practice. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(1):28–40. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spielman AJ, Saskin P, Thorpy MJ. Treatment of chronic insomnia by restriction of time in bed. Sleep. 1987;10(1):45–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Edinger JD, Carney CE. Overcoming Insomnia: A Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy Approach - Therapist Guide. 1st ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Edinger JD, Carney CE. Overcoming Insomnia: A Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy Approach - Therapist Guide. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bootzin RR. A stimulus control treatment for insomnia. Proceedings of the American Psychological Association. 1972;7:395–396. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morin CM. Insomnia: Psychological Assessment and Management. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Steinmark SW, Borkovec TD. Active and placebo treatment effects on moderate insomnia under counterdemand and positive demand instructions. J Abnorm Psychol. 1974;83(2):157–163. doi: 10.1037/h0036489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Edinger JD, Wohlgemuth WK, Radtke RA, Marsh GR, Quillian RE. Cognitive behavioral therapy for treatment of chronic primary insomnia: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001;285(14):1856–1864. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.14.1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]