Abstract

Using an understandable measure to describe subsequent disabilities after stroke is important for clinical practice, and practitioners often use multiple measures that contain different scoring systems and scales to rate activities of daily living (ADL) independence. Therefore, we compared the construct of independence in five measures used with stroke survivors (the Glasgow Outcome Scale, 5-point version, Glasgow Outcome Scale, 8-point version, Modified Rankin Scale, Barthel Index, and the Performance Assessment of Self-Care Skills). The Rasch analysis Partial Credit Model converted items from these measures to a single metric yielding an item difficulty hierarchy of all items from the five measures. Results showed that the five measures evaluated independence of the stroke survivors somewhat differently. Data from the five measures should be interpreted carefully because other concepts or constructs in addition to ADL independence are included in some of the measures. Rasch diagnostics regarding construct validity and reliability of the combined five measures also indicated that these measures are not interchangeable. Although the items of the combined 5 ADL measures were unidimensional, they measured independence from multiple perspectives and the scale of the combined measures was not linear.

Keywords: Activities of Daily Living, Disability Evaluation, Rasch Analysis, Stroke

Stroke (cerebrovascular accident or CVA) is one of the leading causes of disability in the United States, with approximately 780,000 people experiencing new or recurrent strokes each year. About 15% to 30% of stroke survivors have permanent disability (American Heart Association, 2008). In rehabilitation, a functional status assessment is used to identify disabilities in activities of daily living (ADL), and functional status is usually synonymous with independence in performing ADL (P. W. Duncan, Jorgensen, & Wade, 2000; Rogers & Holm, 1998; van Boxel, Roest, Bergen, & Stam, 1995). Duncan, Jorgensen, and Wade (2000) suggested that ADL should be the primary functional status measure in stroke rehabilitation due to their relative objectivity, simplicity, and relevance to patients.

Multiple instruments are available to measure functional independence in the stroke survivors. While the Functional Independence Measure (FIM) (UDSMR, 1997) is the most commonly used in rehabilitation hospitals (AHRQ, 1995; Duncan et al, 2005), the Glasgow Outcome Scales (Jennett & Bond, 1975; (Jennett & Bond, 1975; Jennett, Snoek, Bond, & Brooks, 1981), the modified Rankin Scale (van Swieten, Koudstaal, Visser, Schouten, & van Gijn, 1988), and the Barthel Index (Wade & Collin, 1988) are among the most commonly used outside of rehabilitation. (Johnston, Wagner, Haley, & Connors, 2002; Kasner, 2006; Quinn, Dawson, Walters, & Lees, 2008; Uyttenboogaart, Stewart, Vroomen, De Keyser, & Luijckx, 2005). Although each instrument provides a measure of independence in ADL, each includes different items and involves a different rating scale. The Glasgow Outcome Scale - 5 point version (GOS5) includes severe and moderate (independent but disabled) disability, as well as vegetative state, consciousness and recovery status, and has scores ranging from 1 (death) to 5 (good recovery). The Glasgow Outcome Scale - 8 points extends the GOS5 and includes dependence, partial independence, and independence in ADL as well as wakefulness, communication, signs, symptoms, and complaints, and scores range from 1 (death) to 8 (full recovery). The modified Rankin Scale has five levels of disability as well as required nursing care, continence, assistance needed and symptoms, and scores range from 0 (no symptoms at all) to 6 (death). The Barthel Index consists of 10 basic activities of daily living (BADL) (e.g., feeding, bowels, grooming). Each item has its own rating criteria and yields a score from 0 to 3. The 10 items are summed to obtain a total score. Lower scores indicate less independence and higher scores indicate more independence. Differences in items and scales make it difficult to understand, for example, how clients' scores on the modified Rankin Scale relate to their scores on the Barthel Index. While all of these instruments include measurement of the construct of independence in ADL, they cannot be compared unless they are placed on a common ruler or metric. Rasch analysis provides an analytical tool for describing the continuum of independence in ADL, by plotting all items from multiple measures along the same item difficulty ruler, and also plotting each client's overall person ability on the multiple measures. This allows practitioners to visualize their clients' overall ability in relation to multiple measures, and compare similar items from different tools.

This study compared the functional status of stroke survivors at 3-months post stroke on four tools commonly used on stroke services: Glasgow Outcome Scale - 5-points, Glasgow Outcome Scale - 8 points, the modified Rankin Scale, and the Barthel Index, with the Performance Assessment of Self-Care Skills (Holm & Rogers, 2008), a performace-based observational tool.

Methods

Participants

Data for this study were derived from a large prospective stroke study. Participant inclusion criteria were: (a) admission to the university-affiliated medical center, (b) diagnosis of acute stroke (ischemic or hemorrhagic), (c) availability of radiologic data (e.g., CT scan, MRI, and or Xenon quantitative cerebral blood flow [ExCT qCBF]), and (d) physician approval. There were no exclusion criteria in the large study based on gender, race, or ethnicity. Those living more than 150 miles from the hospital were excluded.

Instruments

Glasgow Outcome Scale, 5-Point Version (GOS5)

The GOS (Jennett & Bond, 1975) was used to rate communication and independence in ADL. It is a classification scale for disability and has acceptable reliability and validity (Jennett et al., 1981). Because GOS5 is frequently used in stroke services, we included data from this tool.

Glasgow Outcome Scale, 8-Point Version (GOS8)

The original GOS5 was extended to an 8-point scale, where scores 3, 4, and 5 in the GOS5 were each expanded to two categories. The extended scale is more sensitive than the GOS5 for measuring various levels of physical and mental impairment, and disability. It has acceptable reliability and validity (Jennett et al., 1981). Because the description for each level of disability in the GOS8 is more precise than in the GOS5, we included it also.

Modified Rankin Scale (mRS)

The mRS is a 5-point scale used to rate disability and need for assistance. It is the most commonly used outcome classification scale for disabilities after stroke and has excellent construct validity (Tilley, Marler, Geller, & National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke [NINDS] rt-PA Stroke Trial Study, 1996), and adequate inter-observer reliability (van Swieten et al., 1988; C. D. A. Wolfe, Taub, Woodrow, & Burney, 1991).

Barthel Index (BI)

The BI was used to rate independence in 10 basic activities of daily living, using self-report. Items are rated on a variable scale ranging from 2 points to 4 points. It has demonstrated construct validity, concurrent validity (Wade & Collin, 1988) and predictive validity (Granger, Hamilton, & Graesham, 1988) as well as excellent interrater reliability (Shinar, Gross, Bronstein, & Licata-Gehr, 1987).

Performance Assessment of Self-Care Skills (PASS)

The PASS, a standardized criterion-referenced instrument, was used to rate the performance of 26 tasks, spanning 4 domains -- Functional Mobility (5 items), BADL (3 items), Physical Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (PIADL) (4 items) and Cognitive Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (CIADL) (14 items). Because of missing data for the oven use item, it was excluded, yielding 25 items for data analysis. Independence is rated by the examiner using a 4-point scale based on established task criteria and the level and frequency of assistance required for task initiation, maintenance, or completion. The PASS has demonstrated content validity (Holm & Rogers, 2008), inter-observer and test-retest reliability (Chisholm, 2005).

Procedures

At the 3-month follow-up, the ADL assessments were administered by faculty of the Department of Occupational Therapy (4 occupational therapists and one physical therapist), each of whom was trained to a minimum interobserver standard of >90% with the criterion assessor. The order of administration followed clinical protocols, informant-reports (GOS5, GOS8, mRS, and BI) followed by performance testing (PASS). Redundancy was avoided because each of the tools used different descriptors and wording. Data were collected in participants' current living environments at the 3-month follow-up.

Data Analysis

Descriptives

Descriptive statistics were calculated using SPSS version 14.0 (SPSS Inc., 2005) for all demographic, pathology, and ADL functional status variables. The amount of missing data was about 0.008 of the total dataset. Missing data were handled using linear interpolation, an SPSS estimation method for replacing missing values, according to like subjects (i.e., participants with left or right hemispheric strokes). The last valid value before the missing value and the first valid value after the missing value were used for the interpolation. The missing value is the median value of its valid, surrounding values. This procedure was done before running Rasch analysis.

Rasch Analysis

Rasch analyses were used to transform ordinal data, such as scores from the BI, into interval data, or logits (log odds units). This enabled the unit intervals between locations on a logarithmic scale to have a consistent value or meaning. The difficulty of the item and the ability of the person are determined by success probabilities of the item and person. Hierarchies of task difficulty and person ability are established using logits. A score of zero was the midpoint of difficulty. Items with more positive logit values were harder to perform, while those with more negative values were easier to perform. In contrast, persons with more positive logit values had a greater likelihood of performing tasks independently than persons with lower or negative logit values. Rasch analysis was performed using WINSTEPS version 3.64.1 (Linacre, 2007).

While Rasch analysis can convert ordinal data into interval data, the validity and reliability of the converted data depend on whether specific procedures were adhered to, as well as the results of several diagnostic tests. Procedures include choosing the correct Rasch model for analysis (e.g., dichotomous model, rating scale model, partial credit model), and developing an anchor dataset for establishing item difficulty (Bond & Fox, 2007). Diagnostic tests for construct validity include fit statistics, principal component analysis, and scale linearity. Diagnostic tests for reliability include calculation of an item reliability index, person reliability index, person separation index, and Cronbach's alpha.

Rasch Procedures

Partial Credit Rasch Model (PCM)

To compare the 5 functional status measures (the GOS5, GOS8, mRS, BI, and PASS), items from these measures were combined into a single metric (5-measures) using the PCM, and item difficulty and person ability across measures were examined. The PCM allows items with various rating scales to be analyzed together and keeps the distances between items' constant (Bond & Fox, 2007; Linacre, 2007).

Anchoring Item Values

To maintain the invariance of items in a dataset, before analyzing a subset of data, one can anchor the item values (Bond & Fox, 2007; Dallmeijer et al., 2005; Tesio, 2003). This step allows the item difficulty hierarchy to be fixed, and analyses of person abilities to be calculated for a specific population (e.g., stroke survivors) across contexts (i.e., home versus clinic) and study phases (i.e., 3, 6, 9, or 12-months). Thus, the values of person ability logits are calculated and will vary based on group, time or setting, but the anchored values of item difficulty logits will remain the same (Bond & Fox, 2007; Linacre, 2007).

Rasch Diagnostics: Construct Validity

Fit statistics

The infit and outfit statistics provide information about how to interpret the data precisely if any discrepancy occurs between observed responses and model-predicted responses. If the data fit perfectly with the Rasch model, the tool being used to test human performance is considered stable and “contributes to the measurement of only one construct” (Bond & Fox, 2007, p. 35). Both infit and outfit statistics are reported as mean squares (MNSQ). According to Bond and Fox, for clinical observation tools, a reasonable task mean square error range for infit and outfit statistics is 0.5 to 1.7. Misfit items with both infit and outfit mean square error values other than the suggested level, ≤ 0.5 or ≥ 1.7, need to be examined more closely.

Principal component analysis (PCA) of Rasch residuals

PCA of Rasch residuals is an advanced method of determining the deviations from the assumption of unidimensionality (i.e., a single dimension such as independence is being measured) in the Rasch model. Potential multi-dimensions of the measurement construct, other than the main dimension (e.g., independence), is revealed with PCA (Bond & Fox, 2007). The PCA yields the variances explained or unexplained by the model. Among the unexplained variances, up to 5 contrasts (or additional dimensions) are identified (Linacre, 2007). In addition to the percentages for these explained or unexplained variances, the eigenvalues are calculated to represent the amount of variance explained by each contrast. After extracting the explained variance, PCA provides a unique Rasch factor analysis to identify a common variance of subset items in the residuals in the first contrast, the largest secondary dimension of the measures. There are rules to discriminate whether the whole dataset is good and represents the unidimensionality of the total measurement constructs: (1) the explained variance by the model is greater than 60%, (2) the unexplained variance of the first contrast is less than 5% or (3) the eigenvalue of the unexplained variance by the first contrast is smaller than 3.0 (Linacre, 2007). Finally, the ratio of the eigenvalues of a contrast to the units (in eigenvalues) of the explained variance in the Rasch model, namely the factor sensitivity ratio, describes the impact of the item residuals in this contrast (a subscale) to the stability of the unexplained variances after the primary Rasch measure was extracted. The smaller the number of the ratio, the better (Bond & Fox, 2007; Linacre, 2007).

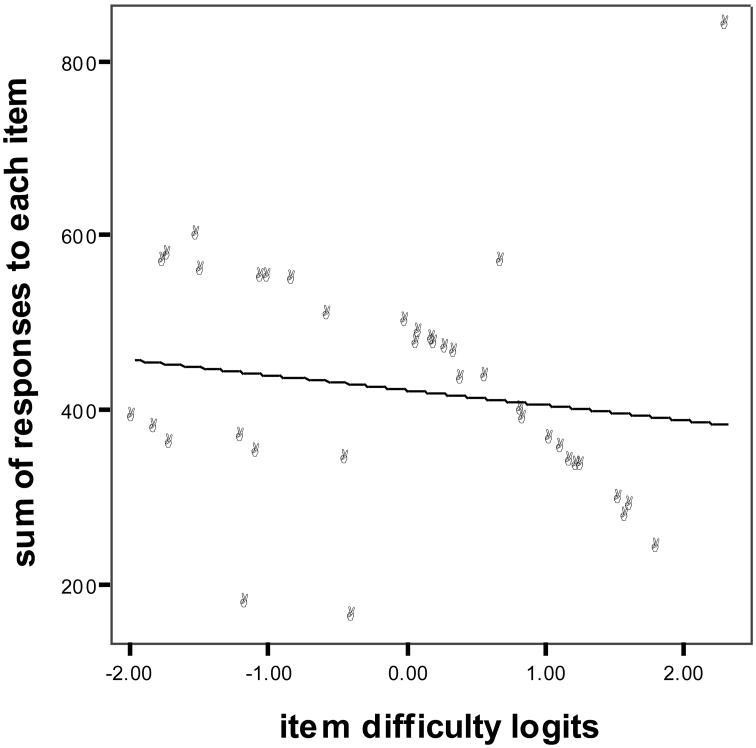

Scale linearity

Scale linearity is derived by plotting the raw scores (sum of the scored responses to each item) against the item difficulty logits. The closer the curve is to the ordinary least square regression line, the more linear the scale (F. Wolfe et al., 2000).

Rasch Diagnostics: Reliability

Item reliability

The item reliability index indicates the consistency of the item difficulty hierarchy if these items were administered to another sample of the same size, with the same traits. A higher value of the item reliability index implies that there is a wider range of item difficulty and a larger sample size (Bond & Fox, 2007; Linacre, 2007).

Person reliability

The person reliability index indicates the expected replicability of the ordering of the clients if these clients were administered another set of items measuring the same construct. A reliability value higher than 0.80 means that the more independent performers can be reliably distinguished from the less independent performers, while a reliability of 0.50 means that the performance differences may be due to random chance. An alternative method to express reliability is the person separation index, indicating the stability of the person stratification levels of a measure. A person separation index higher than 2 implies good test reliability, and 1 implies the differences of the persons within the sample may be due to measurement error (Bond & Fox, 2007; Fisher Jr., 1992; Linacre, 2007; Wright, 1996; Wright & Masters, 1996). Cronbach's alpha is also calculated by WINSTEPS. It indicates the internal consistency of an instrument (Bond & Fox, 2007; Linacre, 2007; Portney & Watkins, 2000). If a value approaches 0.90, the instrument is considered internally consistent. Moderate consistency of an instrument is interpreted if a value is between 0.70 and 0.90 (Portney & Watkins, 2000).

Results

Participants at 3 Months Post-Stroke

Demographic and Pathology Characteristics

The 3-month dataset contained 68 participants. The sample was predominantly male (63.2%), white (97.1%), and had a mean age of 65.53 years. The participants with ischemic stroke constituted 85.3% of the sample. Participants with left hemispheric stroke constituted 57.4% of the sample. There was no significant difference in the number of participants with left and right hemispheric strokes (χ2 = 1.47, 1df, p = .23). Three month assessments were conducted in participants' current living environments: homes (88.3%), long-term care facilities (10.3%) or rehabilitation centers (1.4%). Other demographic and pathology data related to stroke are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Participants' Demographic and Pathology Characteristics at 3-Months Post-Stroke.

| 3-months post-stroke (N = 68) | |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male (%) | 63.2 |

| Age, years (M, SD) | 65.53 (14.03) |

| Ethnicity | |

| White (%) | 97.1 |

| Black (%) | 1.5 |

| Other (%) | 1.5 |

| Stroke location | |

| Left Hemisphere (%) | 57.4 a |

| Right Hemisphere (%) | 42.6 a |

| Cerebellum (%) | N/A |

| Brainstem (%) | N/A |

| Stroke type | |

| Ischemic (%) | 85.3 |

| Hemorrhagic (%) | 14.7 |

| Living environment | |

| Home (%) | 88.3 |

| Long-term care facility (%) | 10.3 |

| Rehabilitation center (%) | 1.4 |

| Had prior CVA (%) | 7.4b |

| Has history of hypertension (%) | 63.2b |

| Has history of cardiac medication use (%) | 42.6b |

| Has history of diabetes mellitus (%) | 26.5b |

| Current cigarette smoker (%) | 23.5b |

| History of alcohol abuse (%) | 5.9b |

| History of atrial fibrillation (%) | 13.2b |

| Used antiplatelet medication in week prior to stroke (%) | 35.3b |

Note:

No significant difference (χ2(1) = 1.47, p = .23) between the percentages of the participants with left versus right hemispheric stroke.

n = 66 for each characteristic.

ADL Functional Status Measures

Table 2 summarizes the ADL functional status of the participants at 3-months post-stroke. For the 68 participants, the mean score on the GOS5 was 3.78, indicating they had moderate disability, and on the GOS8 the mean score was 4.91, indicating that they were independent in ADL, but unable to resume previous activities either at work or socially. The participants demonstrated moderate to slight disability on the mRS, with a mean score of 2.44, indicating their abilities ranged from “unable to carry out all previous activities but able to look after own affairs without assistance” to “requiring some help but able to walk without assistance.” The mean of the summed scores of all BI items (on a 20-point scale) was 17.07, showing that the participants were moderately dependent on others (Anemaet, 2002; Shah, Vanclay, & Cooper, 1989). Finally, the mean score of the PASS was 1.82, indicating that, on average, the participants usually required verbal assistance and occasionally required physical assistance to perform tasks (Holm & Rogers, 2008). Overall, the measures revealed that stroke survivors at 3-months post-stroke were not independent in all ADL.

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics of Functional Status Measures (N = 68).

| Functional status measure | Mean | Range of sample | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| GOS5 | 3.78 | 3 – 5 | 0.86 |

| GOS8 | 4.91 | 3 – 8 | 1.50 |

| mRS | 2.44 | 0 – 5 | 1.20 |

| BIa | 17.07 | 0 – 20 | 5.18 |

| PASSb | 1.82 | 0 – 3 | 0.89 |

Note. GOS5 = Glasgow Outcome Scale, 5-point version. GOS8 = Glasgow Outcome Scale, 8-point version. mRS = Modified Rankin Scale. BI = Barthel Index. PASS = Performance Assessment of Self-Care Skills.

Descriptive statistics of BI from the summed scores of all items (20-point version).

Descriptive statistics of PASS from the average of the independence mean scores from each task.

Diagnosis of Rasch Analysis: Construct Validity

Fit Statistics

Rasch analysis was used to analyze 211 administrations of the 5 measures (the GOS5, GOS8, mRS, BI and PASS) to stroke surviviors for establishing the anchor dataset. No item of the combined measures had both fit statistics values ≤ 0.5 and ≥ 1.7. According to Bond and Fox (2007), data from the tool are stable and “contribute to the measurement of only one construct” (p. 35).

Principal Component Analysis of Rasch Residuals

The Rasch model explained 99.9% of the total variance. The unexplained variance for the 5-measures was 0.1%, and the first contrast in the residuals explained less than 0.1% of the variance. The eigenvalue of the first contrast was 5.3, however, the factor sensitivity ratio was 0.00014, indicating that, clinically, the impact of the first contrast was too small to influence how to measure or interpret the functional status of stroke survivors. In summary, for the 5-measure, single metric combined scale, the construct of independence was considered unidimensional.

Scale Linearity

The R2 linearity value of the scale linearity plot was 0.03, indicating that about 3% of the variance could be explained by the model (Portney & Watkins, 2000). It also indicated that the 5-measure scale was not linear. The degree of change in one part of the scale was not equivalent to the same degree of change in another part of the scale (see Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Scale linearity of the 5-measures. Each dot represents one item of the 5 functional status measures. They were plotted by their item difficulty logits (x-axis) and sum of responses to each item in the Rasch analysis (y-axis). The line is the ordinary least squares regression of y on x.

Diagnosis of Rasch Analysis: Reliability

Item Reliability

The item reliability index of the 5-measure scale was 0.99, which indicated that the item difficulty hierarchy would be consistent in other populations with the same traits and same sample size as our data.

Person Reliability

The person reliability index of the 5-measure scale was 0.91, indicating that the persons who were more independent could be distinguished reliably from those who were less independent with the 5-measure scale. The person separation index of the 5-measure scale was 3.28, which indicated excellent stability of the person ordering. The internal consistency of the scale was also excellent with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.97. Thus, the 5-measure scale was extremely reliable for evaluating functional status independence of stroke survivors.

Outcomes of the Rasch Analysis Partial Credit Model

Item Hierarchy

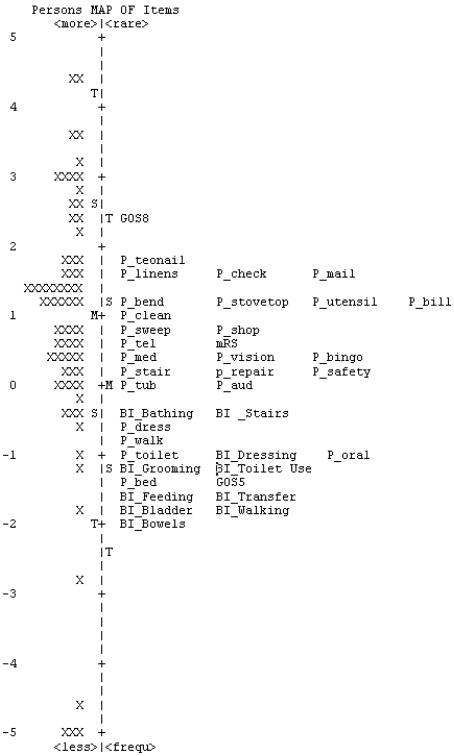

The item hierarchy was ordered based on item difficulty logits. The GOS8 was the most difficult item in the 5-measure scale for the stroke participants, followed by 11 PASS items. The 11 PASS items were IADL tasks, except for the task of trimming toenails. These 11 items included some IADL items with a cognitive emphasis (i.e., mailing, checkbook balancing, stovetop use), and some with a physical emphasis (i.e., changing bed linens, carrying garbage). These items were followed by the mRS. The easiest items for the stroke survivors were 5 BI items and the GOS5 (see Table 3).

Table 3. Fit Statistics and Rasch Item Difficulty Logits of the Combined 5-Measure Scale.

| MOST DIFFICULT | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Instrument | Task/Item | Measure | Infit MNSQ | Outfit MNSQ | Raw |

| GOS8 | 2.31 | 1.02 | 1.01 | 837 | |

| PASS | Trimming toenails | 1.82 | 1.56 | 2.08 | 239 |

| PASS | Mailing | 1.63 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 287 |

| PASS | Changing bed linens | 1.59 | 1.30 | 2.42 | 274 |

| PASS | Checkbook balancing | 1.54 | 1.18 | 1.43 | 293 |

| PASS | Bill paying | 1.27 | 1.08 | 0.97 | 331 |

| PASS | Carrying garbage | 1.24 | 1.39 | 2.18 | 333 |

| PASS | Using sharp utensils | 1.20 | 0.83 | 0.51 | 338 |

| PASS | Stovetop use | 1.13 | 0.63 | 0.36 | 352 |

| PASS | Cleanup after meal preparation | 1.05 | 0.59 | 0.29 | 362 |

| PASS | Shopping | 0.85 | 0.94 | 0.76 | 386 |

| PASS | Sweeping | 0.84 | 1.03 | 0.68 | 396 |

| mRS | 0.69 | 0.86 | 0.84 | 566 | |

| PASS | Telephone use | 0.58 | 0.93 | 0.53 | 433 |

| PASS | Medication management | 0.41 | 1.19 | 1.19 | 432 |

| PASS | Obtaining information-visual | 0.36 | 1.57 | 4.81 | 462 |

| PASS | Playing bingo | 0.30 | 1.39 | 8.83 | 467 |

| PASS | Small repairs | 0.22 | 1.04 | 0.80 | 471 |

| PASS | Stair use | 0.20 | 1.14 | 1.76 | 477 |

| PASS | Home safety | 0.11 | 1.01 | 0.78 | 485 |

| PASS | Bathtub/Shower transfers | 0.08 | 1.24 | 1.65 | 472 |

| PASS | Obtaining information-auditory | 0.00 | 1.49 | 2.40 | 497 |

| BI | Bathing | -0.38 | 0.70 | 0.45 | 160 |

| BI | Stairs | -0.43 | 0.82 | 0.50 | 339 |

| PASS | Dressing | -0.55 | 0.96 | 0.70 | 606 |

| PASS | Indoor walking | -0.81 | 1.38 | 1.01 | 546 |

| PASS | Toilet transfers | -0.99 | 0.90 | 0.62 | 548 |

| PASS | Oral hygiene | -1.03 | 0.81 | 0.51 | 549 |

| BI | Dressing | -1.06 | 0.66 | 0.48 | 348 |

| BI | Grooming | -1.14 | 0.76 | 0.46 | 176 |

| BI | Toilet use | -1.18 | 0.58 | 0.27 | 365 |

| PASS | Bed transfers | -1.47 | -0.93 | 0.76 | 556 |

| GOS5 | -1.49 | 0.65 | 0.56 | 596 | |

| BI | Feeding | -1.69 | 1.22 | 1.10 | 358 |

| BI | Transfer (bed-chair) | -1.70 | 0.77 | 0.26 | 574 |

| BI | Walking | -1.74 | 0.71 | 0.41 | 565 |

| BI | Bowels | -1.96 | 1.05 | 0.93 | 387 |

| BI | Bladder | -1.80 | 0.97 | 0.90 | 376 |

|

| |||||

| LEAST DIFFICULT | |||||

Note. Measure = Item difficulty logits; MNSQ = Mean Square. Raw = Sum of the scored responses to an item; GOS8 = Glasgow Outcome Scale, 8-point version; PASS = Performance Assessment of Self-care Skills; mRS = Modified Rankin Scale; BI = Barthel Index. GOS5 = Glasgow Outcome Scale, 5-point version.

Person Ability

The Rasch person ability logits of the 5-measure scale were calculated based on the anchored item values of the scale, and represented the functional status of the participants at 3-months post-stroke. The histogram (not shown) was normally distributed, implying that the items of the 5-measure scale were responsive to all different levels of functional status of stroke survivors at 3-months post-stroke.

Item-Person Map

Figure 2 presents the item-person map for the 5-measure scale. The map contrasts the difficulties of the items from the 5 measures along the item difficulty logit scale against the distribution of person abilities at 3-months post-stroke, along the person ability logit scale. The map shows that a stroke survivor whose ability logit value was the same as the difficulty logit value of the GOS8 had a 50% probability of being rated the highest score (full recovery) in the GOS8, and would have a greater chances of being rated fully independent in all BADL and IADL tasks in the PASS, BI, mRS and GOS5, which are located lower on the item difficulty hierarchy. Similarly, one participant, whose ability logit value was -1, had a 50% probability of being rated the highest score (3) on PASS-toileting and oral hygiene items, and the highest score (2) on the BI dressing item. It is likely that she would consistently have ≥ 50% probability of being totally independent in all items below her on the item hierarchy (e.g., BI Grooming, BI Toilet use, and all items below them), and similarly, she would consistently have ≤ 50% probability of being totally independent in all items higher on the item hierarchy (e.g., PASS walk and PASS dress, and all items above them).

Figure 2.

Item-person map for the 5-measures. To the left of the dashed line (the logit scale) is the person ability scale, distributed from persons with the greatest ability at the top to the least ability at the bottom. Each X represents a person in the sample. To the right of the dashed line is the item difficulty scale distributed from the most difficult item at the top to the easiest item at the bottom. Along the logit scale, “M” represents the mean person ability or item difficulty estimate, “S” represents the location of one standard deviation (SD) from the mean estimates, and “T” is the second SD away from the mean estimates. “P_” items = Performance Assessment of Self-Care Skills; “BI_” items = Barthel Index; GOS5 = Glasgow Outcome Scale - 5 pt. version; GOS8 = Glasgow Outcome Scale - 8 pt. version; mRS = Modified Rankin Scale.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to compare five functional status measures which address independence in ADL, but use different items and scales. In a sample of stroke survivors at 3-months post-stroke, the separate validities and reliabilities of each tool were first confirmed from the literature, and then the Rasch PCM was used to combine the items so that we could compare them on a common metric. Our findings from Rasch analysis diagnoses indicated that independence was the main construct being measured. However, despite the fact that the unidimensionality was excellent, the scale of the combined 5-measure scale was not linear because the three global measures (GOS5, GOS8, mRS) included not only independence in ADL, but also multiple other constructs (e.g., level of consciousness, signs/symptoms, recovery, complaints, and level of nursing care). The consequence of including multiple constructs within each rating was that the combined 5-measure scale could not sensitively detect small changes in the ADL independence of stroke survivors and therefore would not be useful clinically (Portney & Watkins, 2000). The non-linearity of the scale also suggests that the tools are not interchangeable.

The mixing of constructs was also seen in the item-person map. Even though the item hierarchy and person order were stable for this metric, the item-person map of the 5-measures showed that the rating scores of the three global measures were misleading for interpreting ADL independence. In the map, the three global measures did not cluster together, as expected, but were distributed over the total hierarchy, with the GOS8 being the hardest, the mRS in the middle, and the GOS5 being the easiest. Their rankings in the total hierarchy also reflect their level of detail regarding independence in ADL. For example, moderate disability among the three tools varies widely in detail: GOS8 describes moderate disability as “independent in activities of daily life, for instance can travel by public transport; not able to resume previous activities either at work or socially; despite evident post-traumatic signs, resumption of activities at a lower level is often possible.” The mRS describes moderate disability as “requiring some help, but able to walk without assistance,” and the GOS5 simply uses the term “moderate disability.”

Based on this hierarchy, persons whose abilities were at the same level as the GOS5 or mRS, had a 50% probability of being rated with the highest score on the GOS5 (i.e., good recovery) or the mRS (i.e., no symptoms at all). However, the map also illustrated that for the GOS5, those participants would only have reported being able to accomplish the most basic BADL items on the BI, and only 1 of the PASS items (bed transfers). Likewise for the mRS, the map indicates that those participants would still have problems with many PASS cognitive instrumental activities of daily living items. Therefore, the item-person map of the 5-measure scale shows that the multiple constructs in the content of the global measures impacts the interpretation of these measures for independence in ADL in stroke survivors at 3-months post-stroke.

Our data showed that most participants at 3-months post-stroke were able to take care of their BADL. This finding was supported by the literature that indicated early mobilization and return to self-care are usually the primary intervention goals in acute stroke rehabilitation (Tyson & Turner, 2000; Woodson, 2002). However, at 3-months post acute care, our participants were still challenged in the performance of the more complex IADL, which are not usually assessed during inpatient rehabilitation, and are not included in measures such as the Functional Independence Measure (Linacre, Heinemann, Wright, Granger, & Hamilton, 1994) or Medicare's mandated Inpatient Rehabilitation Facility Patient Assessment Instrument (IRF-PAI) (CMS, 2002). This finding is clinically relevant for stroke survivors, because it is independence in the more complex IADL that enables them to remain in the community. As such, occupational therapists need to assess, and if appropriate provide intervention for, relevant and meaningful IADL of stroke survivors during rehabilitation. Moreover, when participants self-reported their functional status on the BI, they tended to overestimate their abilities. This was apparent on the item-person map with items that were common to both the BI and the performance-based PASS. Of the 6 common items (stair use, dressing, walking, grooming, toilet use, and transfers), all PASS items were mapped as more difficult on the item hierarchy than their BI counterparts. The different assessment methods could be responsible for the difference. Findings from previous literature with other populations has shown that PBO assessments allow researchers or rehabilitation practitioners to gather more detailed and specific information about the processes of executing ADL tasks (Finlayson, Havens, Holm, & Denend, 2003).

Limitations and Recommendations

The findings of the current study must be interpreted with its limitations in mind. Although our anchor dataset included 211 stroke survivors, our sample for this study was smaller, with only 68 participants. Our sample also included participants with ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes, and the different mechanisms in the two types of stroke may have differentially influenced the severity of disabilities in the sample. Also, because this was a secondary analysis of a completed dataset, some desirable variables were not available in the original dataset, such as specific brain lesion locations. In addition, all the rich information yielded from the Rasch analysis could not be addressed in this study because the current study was delimited to exploration of the construct of independence among the five measures. Future studies should use a more homogeneous sample (e.g., ischemic stroke) to explore global measures and task-specific measures that are commonly used to determine the functional status of stroke survivors beyond discharge from rehabilitation. Method of assessment should also be considered in such analyses (e.g., clinical observation, self-report, performance-based observation).

Summary

The current study compared the construct of independence in five functional status measures (mRS, GOS5, GOS8, BI, and PASS) used with stroke survivors. The findings showed that the tools behaved differently when combined in a common metric. The three global measures (mRS, GOS5, and GOS8) made the combined measure non-linear because they also measured other constructs in addition to independence. Clinically, the data from the multiple measures should be interpreted carefully because the information is not interchangeable. Measures addressing multiple constructs also impact the interpretation of ADL independence for stroke survivors, which could further influence rehabilitation referrals and outcomes.

References

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Assessment methods for patients with strokes [Electronic Version] AHCPR Archived Clinical Practice Guidelines. 1995 Retrieved Aug. 7, 2008 from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/bv.fcgi?rid=hstat6.section.27581.

- American Heart Association. Heart and Stroke Statistical Update - 2008. Circulation. 2008;117:e25–e146. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.187998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anemaet WK. Using standardized measures to meet the challenge of stroke assessment. Topics in Geriatric Rehabilitation. 2002;18(2):47–62. [Google Scholar]

- Bond TG, Fox CM. Applying the Rasch model: Fundamental measurement in the human sciences. 2nd. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlabaum; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Inpatient Rehabilitation Facility - Patient Assessment Instrument (IRF-PAI) 2002 (Publication. Retrieved June,22, 2008, from Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/cmsforms/downloads/cms10036.pdf.

- Chisholm D. Disability in older adults with depression. University of Pittsburgh; Pittsburgh, PA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Dallmeijer AJ, Dekker J, Roorda LD, Knol DL, van Baalen B, de Groot V, et al. Differential item functioning of the functional independence measure in higher performing neurological patients. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 2005;37:346–352. doi: 10.1080/16501970510038284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan PW, Jorgensen HS, Wade DT. Outcome measures in acute stroke trials: A systematic review and some recommendations to improve practice. Stroke. 2000;31:1429–1438. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.6.1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan PW, Zorowitz R, Bates B, Choi JY, Glasberg JJ, Graham GD, et al. Management of Adult Stroke Rehabilitation Care: A Clinical Practice Guideline. Stroke. 2005;36:e100–e143. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000180861.54180.FF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlayson M, Havens B, Holm MB, Denend TV. Integrating a performance-based observation measure of functional status into a population-based longitudinal study of aging. Canadian Journal on Aging. 2003;22:185–195. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher W., Jr Reliability Statistics. Rasch Measurement Transactions. 1992;6:238. [Google Scholar]

- Granger CV, Hamilton BB, Graesham GE. The stroke rehabilitation outcome study - Part I: General description. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 1988;69:506–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm MB, Rogers JC. The Performance Assessment of Self-Care Skills. In: Hemphill-Pearson BJ, editor. Assessments in occupational therapy mental health. 2nd. Thorofare, NJ; Slack; 2008. pp. 101–110. [Google Scholar]

- Jennett B, Bond M. Assessment of outcome after severe brain damage: A practical scale. Lancet. 1975;1:480–484. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(75)92830-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennett B, Snoek J, Bond M, Brooks N. Disability after severe head injury: observations on the use of the Glasgow Outcome Scale. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, & Psychiatry. 1981;44:285–293. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.44.4.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston K, Wagner D, Haley EJ, Connors AJ. Combined clinical and imaging information as an early stroke outcome measure. Stroke. 2002;2:466–472. doi: 10.1161/hs0202.102881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasner SE. Clinical interpretation and use of stroke scales. Lancet Neurology. 2006;5:603–612. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70495-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linacre JM. A user's guide to WINSTEPS. 3.64.1. Chicago: MESA press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Linacre JM, Heinemann AW, Wright BD, Granger CV, Hamilton BB. The structure and stability of the Functional Independence Measure. Archives of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation. 1994;75:127–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portney LG, Watkins MP. Foundations of clinical research: Application to practice. 2nd. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn TJ, Dawson J, Walters MR, Lees KR. Functional outcome assessment in contemporary stroke trials. Stroke. 2008;39:692. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2009.00271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers JC, Holm MB. Evaluation of occupational performance areas Section 1: Evaluation of activities of daily living and home management. In: Neistadt ME, Crepeau EB, editors. Willard & Spackman's Occupational Therapy. 9th. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1998. pp. 185–208. [Google Scholar]

- Shah S, Vanclay F, Cooper B. Improving the sensitivity of the Barthel Index for stroke rehabilitation. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1989;42:703–709. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(89)90065-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinar D, Gross CR, Bronstein KS, Licata-Gehr EE. Reliability of the activities of daily living scale and its use in telephone interview. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 1987;67:723–728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SPSS Inc. SPSS for Windows (version 14.0) Chicago: SPSS Inc; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Tesio L. Measuring behaviours and perceptions: Rasch analysis as a tool for rehabilitation research. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 2003;35:105–115. doi: 10.1080/16501970310010448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilley BC, Marler JR, Geller NL National Institute of Neurological Disorders Stroke [NINDS] rt-PA Stroke Trial Study. Use of a Global Test for Multiple Outcomes in Stroke Trials With Application to the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke t-PA Stroke Trial. Stroke. 1996;27:2136–2142. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.11.2136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyson S, Turner G. Discharge and follow-up for people with stroke: What happens and why. Clinical Rehabilitation. 2000;76:1152–1155. doi: 10.1191/0269215500cr331oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uniform Data System for Medical Rehabilitation [UDSMR] Guide for the Uniform Data Set for Medical Rehabilitation (including the FIM instrument (Version 5.1)) Buffalo, NY: State University of New York; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Uyttenboogaart M, Stewart RE, Vroomen PCAJ, De Keyser J, Luijckx GJ. Optimizing Cutoff Scores for the Barthel Index and the Modified Rankin Scale for Defining Outcome in Acute Stroke Trials. Stroke. 2005;36:1984–1987. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000177872.87960.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Boxel YJJM, Roest FHJ, Bergen MP, Stam HJ. Dimensionality and hierarchical structure of disability measurement. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 1995;76:1152–1155. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(95)80125-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Swieten JC, Koudstaal PJ, Visser MC, Schouten HJA, van Gijn J. Interobserver agreement for the assessment of handicap in stroke patients. Stroke. 1988;19:604–607. doi: 10.1161/01.str.19.5.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade DT, Collin C. The Barthel Index: A standard measure of physical disability. International Disability Studies. 1988;10(2):64–67. doi: 10.3109/09638288809164105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe CDA, Taub NA, Woodrow EJ, Burney PGJ. Assessment of scales of disability and handicap for stroke patients. Stroke. 1991;22:1242–1244. doi: 10.1161/01.str.22.10.1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe F, Hawley DJ, Doldenberg DL, Russell IJ, Buskila D, Neumann L. The assessment of functional impairment in fibromyalgia (FM): Rasch analyses of 5 functional scale and the development of the FM health assessment questionnaire. Journal of Rheumatology. 2000;27:1989–1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodson AM. Stroke. In: Trombly CA, Radomski MV, editors. Occupational Therapy for Physical Dysfunction. 5th. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2002. pp. 817–853. [Google Scholar]

- Wright BD. Reliability and separation. Rasch Measurement Transactions. 1996;9:472. [Google Scholar]

- Wright BD, Masters GN. Number of person on item strata. Rasch Measurement Transactions. 1996;16:888. [Google Scholar]