Abstract

Objective

To examine the relationship between physician advice to quit smoking and patient care experiences.

Data Source

The 2012 Medicare Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (MCAHPS) surveys.

Study Design

Fixed‐effects linear regression models were used to analyze cross‐sectional survey data, which included a nationally representative sample of 26,432 smokers aged 65+.

Principal Findings

Eleven of 12 patient experience measures were significantly more positive among smokers who were always advised to quit smoking than those advised to quit less frequently. There was an attenuated but still significant and positive association of advice to quit smoking with both physician rating and physician communication, after controlling for other measures of care experiences.

Conclusions

Physician‐provided cessation advice was associated with more positive patient assessments of their physicians.

Keywords: Survey research and questionnaire design, clinical practice, incentives in health care, Medicare, patient assessment/satisfaction, substance abuse: alcohol/chemical dependency/tobacco

The Medicare Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (MCAHPS) surveys are administered annually by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to collect data on Medicare beneficiaries' health care experiences, whether they are enrolled in fee‐for‐service or Medicare Advantage (managed care). The Affordable Care Act mandates incentive payments to hospitals and quality bonus payments for Medicare Advantage (MA) health plans, based on quality measures that include patient experience data (Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010).

Some health care providers and others are concerned that basing payments on patient experience data might produce clinician incentives that are not in the patient's best medical interest. It has been argued that physicians will be incentivized to give patients medically inadvisable care when patients' preferences deviate from their medical needs, to improve their patient experience survey scores (Johnston 2013). For example, some have argued that incentives might lead to overprescription of narcotics to improve pain control scores on the Hospital CAHPS (HCAHPS) survey (Hanna et al. 2012; Zgierska, Miller, and Rabago 2012) or to prescription of antibiotics for viral infections (Stearns et al. 2009).

Research, however, suggests that patients accept recommendations that may be uncomfortable or unexpected if providers clearly communicate the reasons for their recommendations. For example, parents of children with upper respiratory infections do not mind if their children do not receive expected antibiotics when it is explained why they would not improve their child's condition (Mangione‐Smith et al. 1999); similarly, even patients who request inappropriate antibiotics are more interested in receiving a diagnosis than an antibiotic (Linder and Singer 2003).

One physician behavior that might affect patient reports about care experiences is advice on smoking cessation. According to the 2014 Surgeon General's Report on the Health Consequences of Smoking, tobacco use is the leading preventable cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2014), yet 8 percent of Americans aged 65+ continue to smoke (Agaku, King, and Dube 2012). Seniors' smoking can be expected to “contribute substantially to mortality and morbidity and to aggravate existing chronic conditions” (Burns 2000). United States Public Health Service Clinical Practice guidelines therefore recommend that smokers receive advice to quit smoking at every visit (Fiore et al. 2008). Nevertheless, receipt of advice from physicians to quit smoking is inconsistent (Shadel et al. 2015). Physicians may be concerned that offering smoking advice will harm the physician–patient relationship and worsen the patient's reports of their care. For example, some physicians worry that giving patients such advice will be seen as personal criticism or as advice irrelevant to the problem for which they sought help, leading to shame or defiance (Coleman, Murphy, and Cheater 2000).

Despite such concerns, several studies suggest that patients who are counseled to quit smoking are more, rather than less, satisfied with their care (Barzilai et al. 2001; Conroy et al. 2005; Quinn et al. 2005; Bernstein and Boudreaux 2010). There are at least two possible explanations for such an association. First, smoking cessation advice may cause patients to assess their health care more positively because they think the advice reflects greater physician interest or concern. Alternatively, smoking cessation advice may be a correlate of better health care provision in general. If the former explanation is correct, one could simply assess the association between advice and physician ratings, controlling for potentially confounding patient characteristics. One would then expect stronger associations of cessation advice with experience measures related to the physician–patient relationship than with measures assessing other aspects of care. If the latter is correct, it is also necessary to control for other patient evaluations when assessing the relationship between smoking advice and physician ratings.

In this study, we used data from a large nationally representative sample of seniors, considerably larger than in previous studies of this topic, to study the relationship between physician advice to quit smoking and health care evaluations by older adults. We used data collected using the MCAHPS surveys, the same surveys used to assess performance and calculate Star Ratings and Quality Bonus Payments for Medicare Advantage (MA) plans and prescription drug plans (PDPs). This approach thus allows us to directly assess the basis for physicians' concerns about the possible adverse effect of giving advice to quit smoking on their survey scores.

The MCAHPS patient experience measures also allow us to address different hypotheses regarding the relationship between advice to quit and patient experiences. If cessation advice directly affects the patient's experience of his or her care, we would expect significant associations with dimensions related to the physician, after controlling for other factors. Alternatively if smoking cessation advice is related to better health care in general, we would expect positive associations across the patient experience measures, not only those related to the physician. In such a case, we would expect no association with dimensions related to the physician after controlling for other patient experience measures.

Methods

Data were collected via the 2012 MCAHPS survey (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services 2011), which assesses patients' health care experiences in a representative random sample of Medicare beneficiaries. It is a mail survey with telephone follow‐up of nonrespondents. Analyses presented herein use data from respondents aged 65+ living in the 50 U.S. states and Washington, DC (48 percent response rate).

Respondents were asked, “Do you now smoke cigarettes or use tobacco every day, some days or not at all?” Those answering “every day” or “some days” were asked: “In the last 6 months, how often were you advised to quit smoking or using tobacco by a doctor or other health provider?” with response options “Never,” “Sometimes,” “Usually,” “Always,” and “I had no visits in the last 6 months.” There were 26,432 smokers who responded to questions about advice to quit smoking and indicated that they had a visit in the last 6 months.

Twelve measures of patients' health care experiences in the prior 6 months are the outcomes analyzed: five global ratings and seven composite measures of care. The five global ratings were of respondents' health care, personal physician, specialists, health plan, and PDP, on a scale from 0 (worst possible care) to 10 (best possible care). The seven composite measures were constructed from multiple items measuring patient experiences in five areas: access, physician communication, customer services, prescription plan, and care coordination. Screening questions restricted respondents to those who had the experiences specified.

Responses were given on a Likert scale with response options of always, usually, sometimes, or never. Each composite score is the mean of its constituent items (Martino et al. 2009), which appear in Appendix SA2. For ease of comparisons and interpretation, all MCAHPS measures were linearly rescaled to a 0–100 possible range, so that the transformed score y = 100 × (x − a)/(b − a), where the original score x was on a scale from a to b.

The MCAHPS survey (see Table 1) also elicited respondent sex, age, race/ethnicity, education, self‐rated overall and mental health status, proxy status, living arrangements, and the presence of six medical conditions. Beneficiary coverage type, geographic location, and low‐income status (income <150 percent of the federal poverty line) were obtained from CMS administrative records (Table 1).

Table 1.

Distribution of Demographic Characteristics of Medicare Beneficiaries Who Smokea (N = 26,432) and the Frequency of Physician Advice to Quit by Demographic Characteristic

| Demographic Characteristics among Smokers—Weighted % of All with Specified Characteristic | Percentage of Smokers Who Were “Always” Advised to Quit | |

|---|---|---|

| Overall | 36.8 | |

| Gender | ||

| Male [ref] | 54.6 | 34.7 |

| Female | 45.4 | 39.2*** |

| Age | ||

| 65–69 [ref] | 43.6 | 39.3 |

| 70–74 | 27.2 | 37.8 (NS) |

| 75–79 | 15.6 | 35.4* |

| 80–84 | 8.6 | 31.7** |

| 85+ | 5.0 | 23.3*** |

| Education | ||

| 8th grade or less | 9.4 | 32.8 (NS) |

| Some high school | 13.7 | 38.0 (NS) |

| High school or GED [ref] | 34.6 | 37.1 |

| Less than 4‐year degree | 25.3 | 38.8 (NS) |

| Four‐year college degree | 8.2 | 35.7 (NS) |

| More than 4‐year college degree | 8.8 | 34.1 (NS) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White [ref] | 76.5 | 35.6 |

| Hispanic | 4.5 | 43.8** |

| Black | 10.4 | 41.0** |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 1.9 | 37.7 (NS) |

| Other (American Indian, multiracial, missing) | 6.7 | 40.0 (NS) |

| Smoking frequency | ||

| Every day [ref] | 64.2 | 39.8 |

| Some days | 35.8 | 33.0*** |

| Census Divisionb | ||

| 1. New England [ref] | 3.8 | 45.6 |

| 2. Middle Atlantic | 12.0 | 42.5 (NS) |

| 3. East North Central | 15.8 | 35.8*** |

| 4. West North Central | 7.2 | 30.7*** |

| 5. South Atlantic | 22.0 | 37.1** |

| 6. East South Central | 9.1 | 28.9*** |

| 7. West South Central | 13.4 | 38.5* |

| 8. Mountain | 5.9 | 36.1** |

| 9. Pacific | 10.7 | 37.9* |

Excludes 5.3% of smokers who did not have a health care visit in the last 6 months and the 5.3% of smokers who inappropriately skipped the question about frequency of advice to quit.

Census divisions are created from state of beneficiary residence as follows: New England: CT, MA, ME, NH, RI, VT; Middle Atlantic: NJ, NY, PA; East North Central: IL, IN, MI, OH, WI; West North Central: IA, KS, MN, MO, ND, NE, SD; South Atlantic: DC, DE, FL, GA, MD, NC, SC, VA, WV; East South Central: AL, KY, MS, TN; West South Central: AR, LA, OK, TX; Mountain: AZ, CO, ID, MT, NM, NV, UT, WY; Pacific: AK, CA, HI, OR, WA.

*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001, bivariate test of association with always advised to quit.

Analyses

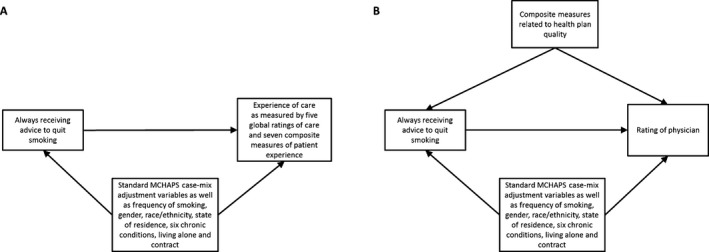

We estimated fixed‐effects linear regression models to assess the associations between physician advice to quit smoking and the 12 patient experiences measures of patient experience among smokers (see Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Logic Models Corresponding to Regressions

Models incorporated standard MCAHPS case‐mix adjustors: age, education, self‐rated general and mental health, proxy status, and low‐income indicators (Martino et al. 2009). We also adjusted for frequency of smoking, gender, race/ethnicity, state of residence, chronic conditions (heart attack, angina, stroke, cancer, COPD, and diabetes), and living alone, variables predictive of both patient experience scores and cessation advice (Beckett et al. 2015; Shadel et al. 2015). We include MA contracts as fixed effects, treating FFS as a single contract. These models predicted each patient experience measure: (1) when all respondents report always being advised to quit (vs. less frequently than always), and (2) when respondents do not report always being advised to quit, controlling for all other predictors.

In a separate model (see Figure 1B), we estimated the association of cessation advice with both physician communication and overall physician rating, further controlling for other care experiences as measured by the other CAHPS composites. To retain all records in these models, we imputed all missing predictors under the missing at random assumption.

All analyses were weighted to represent the Medicare population aged 65+ within each county and MA contract using poststratification weights that used raking (log‐linear weights by iterative proportional fitting) (Deming and Stephan 1940; Purcell and Kish 1980) to match weighted sample distributions. Analyses were performed in SAS, version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, US) and Stata 12 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX), correcting for the design effects of these weights using linearization.

Results

Respondent Characteristics

Characteristics of current smokers responding to the cessation advice question appear in Table 1. A majority was male (55 percent), white (77 percent), and aged 65–74 (71 percent). Most smokers (64 percent) were daily smokers. The rightmost column of Table 1 shows the proportion of smokers in each group who were always advised to quit smoking or using tobacco during health care visits in the last 6 months. Overall, 37 percent of smokers reported that they were always advised to quit. More female smokers reported always being advised to quit than males (39 percent vs. 35 percent), and more smokers always received advice to quit in the younger age groups (39 percent/38 percent of those 65–69/70–74 vs. 23 percent of those 85 or older).

Always being advised to quit was lower among non‐Hispanic whites (36 percent) than Hispanics (44 percent).

Approximately, 40 percent of those who smoked daily always received cessation advice, compared to 33 percent of those who smoked only some days. In addition, fewer respondents always received cessation advice in the East South Central division (29 percent) than in New England (46 percent). Further details of how advice to quit smoking varied across demographic, health plan coverage, and health characteristics of MCAHPS respondents appear elsewhere (Shadel et al. 2015).

Associations between Patient Experiences and Advice to Quit Smoking

As can be seen in Table 2, 11/12 measures were significantly more positive among the 37 percent of smokers who were always advised to quit than those advised to quit less frequently, with no statistically significant difference by advice to quit for the twelfth measure (p > .05). The mean difference between the always‐advised‐to‐quit group and the others varied between 2.22 and 6.33 points across the different CAHPS measures. These differences are substantial; in a previous study, a 3‐point increase on a 0–100 scale of some CAHPS measures was associated with a 30 percent reduction in disenrollment from plans (Cleary 2003). The largest difference (6.33 points) was for the customer service composite, followed by care coordination and getting care quickly composites.

Table 2.

Adjusteda MCAHPS Mean Global Ratings of Care and Composite Measures, by Frequency of Advice to Quit, and Mean Differences

| Advised to Quit Always | Advised to Quit Usually, Sometimes, or Never | Mean Difference | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rating of care | 87.12 (0.06) | 83.88 (0.06) | 3.25 (0.42) | <.001 |

| Rating of physician | 92.05 (0.04) | 89.18 (0.04) | 2.86 (0.34) | <.001 |

| Rating of specialist | 90.89 (0.06) | 88.67 (0.06) | 2.22 (0.49) | <.001 |

| Rating of PDP | 87.28 (0.25) | 84.09 (0.25) | 3.19 (1.02) | .002 |

| Rating of health plan | 86.29 (0.05) | 84.02 (0.05) | 2.26 (0.43) | <.001 |

| Getting prescription drugs | 92.62 (0.24) | 89.80 (0.24) | 2.81 (1.11) | .011 |

| Getting information for drugs | 82.19 (1.43) | 78.59 (1.43) | 3.60 (2.41) | .135 |

| Getting needed care | 89.40 (0.06) | 85.87 (0.06) | 3.53 (0.52) | <.001 |

| Customer service | 80.12 (0.20) | 73.79 (0.20) | 6.33 (1.36) | <.001 |

| Getting care quickly | 73.61 (0.06) | 69.36 (0.06) | 4.25 (0.55) | <.001 |

| Physician communication | 92.27 (0.04) | 88.60 (0.04) | 3.67 (0.37) | <.001 |

| Care coordination | 89.48 (0.04) | 84.84 (0.04) | 4.64 (0.40) | <.001 |

Each column shows mean with standard error given in brackets.

Adjusted for age, education level, self‐rated general and mental health, proxy status, dually eligible for Medicaid, frequency of smoking, gender, race/ethnicity, state of residence, diagnosis with six chronic conditions (heart attack, angina, stroke, cancer, COPD and diabetes), living alone, and contract.

Table 3 presents two models of the association of advice to quit smoking with rating of physician and physician communication. Model 1 is unadjusted for other domains of patient experience and corresponds to results presented in Table 2. In Model 2, after adjusting for getting prescription drugs, getting information for drugs, getting needed care, customer service, getting care quickly, and care coordination, always being advised to quit smoking remains positively associated with rating of physician and physician communication (p < .05 for each), although the strength of the association is diminished by 75–80 percent. Sensitivity analyses (data not shown) found similar results with several alternate parametrizations of the always‐to‐never cessation advice variable.

Table 3.

Linear Regression Models of Rating of Physician and Physician Communicationa by Frequency of Advice to Quit

| Rating of Physician | Physician Communication | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | |

| Advised to quit frequency | ||||

| Always | 2.86 (0.34)*** | 0.62 (0.30)* | 3.67 (0.37)*** | 0.76 (0.30)* |

| Usually, sometimes, or never (ref) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| CAHPS composites (0–100) | ||||

| Getting prescription drugs | 0.02 (0.01)* | 0.04 (0.01)*** | ||

| Getting information for drugs | −0.00 (0.01) | 0.03 (0.01)*** | ||

| Getting needed care | 0.05 (0.01)*** | 0.07 (0.01)*** | ||

| Customer service | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) | ||

| Getting care quickly | 0.07 (0.01)*** | 0.08 (0.01)*** | ||

| Care coordination | 0.41 (0.01)*** | 0.49 (0.01)*** | ||

Model 1 corresponds to results presented in Table 2. Model 2 additionally adjusts for CAHPS composites that do not directly assess physician.

Models also include fixed effects for age, education level, self‐rated general and mental health, proxy status, dually eligible for Medicaid, frequency of smoking, gender, race/ethnicity, state of residence, diagnosis with six chronic conditions (heart attack, angina, stroke, cancer, COPD, and diabetes), living alone, and contract.

*p < .05; ***p < .001.

Discussion

This study found that, among Medicare beneficiaries 65+ who smoke, those who reported always being given advice to stop smoking also reported better health care experiences than those who reported being advised to stop smoking less frequently. This finding agrees with previous smaller studies which show that patients who were counseled to quit smoking were more satisfied with their care than those not (Barzilai et al. 2001; Conroy et al. 2005).

Patients who were always advised to quit smoking by their physician gave more positive ratings of their overall care, their physician, their specialist, and their health plan overall. Scores were higher for such patients across all care domains, including physician communication.

The positive relationship for almost all of the outcome measures, rather than for physician measures alone, suggests a broader mechanism than patients being pleased with receiving smoking cessation advice. Instead, smoking cessation advice is associated with a positive health plan evaluation, and thus it may in part reflect receipt of better care in general. After controlling for the care experience composites that reflect the quality of care experiences more broadly, the positive association between smoking cessation advice and rating of physician and physician communication was attenuated but persisted. This supports the hypothesis that patients who receive advice to quit smoking receive better care in general, with only a small difference attributable to a positive reaction to the physician encounter.

Our study certainly does not suggest any negative effect of physician advice to quit on physician ratings, even after controlling for other care experiences. The data used in this study came from the same CAHPS survey that is used to calculate Star Ratings, and the Quality Bonus Payments for Medicare plans. Hence, this finding indicates that provision of advice which patients may not wish to hear, such as advice on behavior changes, in this case smoking cessation, may not negatively influence survey scores or Quality Bonus Payments. Thus, providers have no disincentive to engage in such practices. These findings support the suggestion from other studies (Mangione‐Smith et al. 1999) that patients do not mind receiving challenging advice, if there is good communication between physician and patient.

Although this study is cross‐sectional, and hence it is difficult to assess causality, the range of patient experience measures in the MCHAPS survey allows us to understand more in depth the relationship between smoking cessation advice and patient's rating of their health care than has previously been possible. A future study might extend this work through analysis of longitudinal data of individuals who change status with respect to receiving smoking cessation advice.

The MCAHPS survey was administered to a nationally representative sample of those aged 65+ who answer questions across all of the care they receive, and thus this study benefits from not being confined to a particular care setting. As this study uses survey data from those aged 65+, our results may not be generalizable to younger age groups; nevertheless, our findings are consistent with a number of other studies looking at this issue in different populations (Barzilai et al. 2001; Conroy et al. 2005; Bernstein and Boudreaux 2010). A further limitation is that self‐reported measures such as those collected in the MCHAPS may be subject to recall bias. However, these measures are widely used to assess care and calculate quality bonus payments for health plans.

Despite these limitations, this study strengthens the evidence that provision of smoking advice at every visit, as recommended by guidelines, does not negatively affect patients' perception of care, as measured using the MCAHPS survey. Thus, physicians should not be concerned that provision of advice on health behaviors such as smoking will negatively affect their own scores on patient experience surveys.

Supporting information

Appendix SA1: Author Matrix.

Appendix SA2: Details of the Seven 2012 MCAHPS Composite Measures.

Acknowledgments

Joint Acknowledgment/Disclosure Statement: We thank Fergal McCarthy for preparing the manuscript. This study was funded by contract HHSM‐500‐2005‐00028I from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to RAND.

Disclosures: None.

Disclaimers: None.

References

- Agaku, I. , King B., and Dube S. R.. 2012. “Current Cigarette Smoking Among Adults—United States, 2011” [accessed on January 2, 2014, 2012]. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6144a2.htm [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Barzilai, D. A. , Goodwin M. A., Zyzanski S. J., and Stange K. C.. 2001. “Does Health Habit Counseling Affect Patient Satisfaction?” Preventive Medicine 33 (6): 595–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckett, M. K. , Elliott M. N., Haviland A. M., Burkhart Q., Gaillot S., Montfort D., and Saliba D.. 2015. “Living Alone and Patent Care Experiences: The Role of Gender in a National Sample of Medicine Beneficiaries.” Journal of Gerontology: Medical Sciences 70 (10): 1242–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, S. L. , and Boudreaux E. D.. 2010. “Emergency Department‐Based Tobacco Interventions Improve Patient Satisfaction.” The Journal of Emergency Medicine 38 (4): e35–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns, D. M. 2000. “Cigarette Smoking Among the Elderly: Disease Consequences and the Benefits of Cessation.” American Journal of Health Promotion 14 (6): 357–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . 2011. Consumer Assessment of Health Providers & Systems (CAHPS): Overview. Baltimore, MD: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Google Scholar]

- Cleary, P. D. 2003. “Beneficiary Reported Experience and Voluntary Disenrollment in Medicare Managed Care.” Health Care Financing Review 25 (1): 55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, T. , Murphy E., and Cheater F.. 2000. “Factors Influencing Discussion of Smoking between General Practitioners and Patients Who Smoke: A Qualitative Study.” The British Journal of General Practice 50 (452): 207. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conroy, M. B. , Majchrzak N. E., Regan S., Silverman C. B., Schneider L. I., and Rigotti N. A.. 2005. “The Association between Patient‐Reported Receipt of Tobacco Intervention at a Primary Care Visit and Smokers' Satisfaction with Their Health Care.” Nicotine & Tobacco Research 7 (Suppl 1): S29–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deming, W. E. , and Stephan F. F.. 1940. “On a Least Squares Adjustment of a Sampled Frequency Table When the Expected Marginal Totals Are Known.” The Annals of Mathematical Statistics 11 (4): 427–44. [Google Scholar]

- Fiore, M. C. , Jaén C., Baker T. B., Bailey W. C., Benowitz N. L., Curry S. J., Dorfman S. F., Froelicher E. S., Goldstein M. G., Froelicher E. S., Healton C. G., P. N., Henderson , Heyman R. B., Koh H. K., Kottke T. E., Lando H. A., Mecklenburg R. E., Mermelstein R. J., Mullen P. D., Orleans C. T., Robinson L., Stitzer M. L., Tommasello A. C., Villejo L., and Wewers M. E.. 2008. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update—Clinical Practice Guidelines. Rockville, MD: United States Public Health Service Clinical Practice Guideline, Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence. [Google Scholar]

- Hanna, M. N. , González‐Fernández M., Barrett A. D., Williams K. A., and Pronovost P.. 2012. “Does Patient Perception of Pain Control Affect Patient Satisfaction Across Surgical Units in a Tertiary Teaching Hospital?” American Journal of Medical Quality 27 (5): 411–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, C. B. 2013. “Patient Satisfaction and Its Discontents.” Journal of the American Medical Association of Internal Medicine 173 (22): 2025–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linder, J. A. , and Singer D. E.. 2003. “Desire for Antibiotics and Antibiotic Prescribing for Adults with Upper Respiratory Tract Infections.” Journal of General Internal Medicine 18 (10): 795–801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangione‐Smith, R. , McGlynn E. A., Elliott M. N., Krogstad P., and Brook R. H.. 1999. “The Relationship between Perceived Parental Expectations and Pediatrician Antimicrobial Prescribing Behavior.” Pediatrics 103 (4): 711–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martino, S. C. , Elliott M. N., Cleary P. D., Kanouse D. E., Brown J. A., Spritzer K. L., Heller A., and Hays R. D.. 2009. “Psychometric Properties of an Instrument to Assess Medicare Beneficiaries' Prescription Drug Plan Experiences.” Health Care Financing Review 30 (3): 41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 . “Publication No. 111–148, 124 Stat 119.”

- Purcell, N. J. , and Kish L.. 1980. “Postcensal Estimates for Local Areas (or Domains).” International Statistical Review 48: 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn, V. P. , Stevens V. J., Hollis J. F., Rigotti N. A., Solberg L. I., Gordon N., Ritzwoller D., Smith K. S., Hu W., and Zapka J.. 2005. “Tobacco‐Cessation Services and Patient Satisfaction in Nine Nonprofit HMOs.” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 29 (2): 77–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadel, W. , Elliott M. N., Haas A., Haviland A. M., Orr N., Farmer Coste M., Ma S., Weech‐Maldonado R., Farley D. O., and Cleary P. D.. 2015. “Clinician Advice to Quit Smoking among Seniors.” Preventive Medicine 70 (1): 83–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stearns, C. R. , Gonzales R., Camargo C. A. Jr., Maselli J., and Metlay J. P.. 2009. “Antibiotic Prescriptions Are Associated with Increased Patient Satisfaction with Emergency Department Visits for Acute Respiratory Tract Infections.” Academic Emergency Medicine 16 (10): 934–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . 2014. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General, 2014. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health. [Google Scholar]

- Zgierska, A. , Miller M., and Rabago D.. 2012. “Patient Satisfaction, Prescription Drug Abuse, and Potential Unintended Consequences.” Journal of the American Medical Association 307 (13): 1377–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix SA1: Author Matrix.

Appendix SA2: Details of the Seven 2012 MCAHPS Composite Measures.