Abstract

Objectives

To compare the efficacy and safety of SB4 (an etanercept biosimilar) with reference product etanercept (ETN) in patients with moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis (RA) despite methotrexate (MTX) therapy.

Methods

This is a phase III, randomised, double-blind, parallel-group, multicentre study with a 24-week primary endpoint. Patients with moderate to severe RA despite MTX treatment were randomised to receive weekly dose of 50 mg of subcutaneous SB4 or ETN. The primary endpoint was the American College of Rheumatology 20% (ACR20) response at week 24. Other efficacy endpoints as well as safety, immunogenicity and pharmacokinetic parameters were also measured.

Results

596 patients were randomised to either SB4 (N=299) or ETN (N=297). The ACR20 response rate at week 24 in the per-protocol set was 78.1% for SB4 and 80.3% for ETN. The 95% CI of the adjusted treatment difference was −9.41% to 4.98%, which is completely contained within the predefined equivalence margin of −15% to 15%, indicating therapeutic equivalence between SB4 and ETN. Other efficacy endpoints and pharmacokinetic endpoints were comparable. The incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events was comparable (55.2% vs 58.2%), and the incidence of antidrug antibody development up to week 24 was lower in SB4 compared with ETN (0.7% vs 13.1%).

Conclusions

SB4 was shown to be equivalent with ETN in terms of efficacy at week 24. SB4 was well tolerated with a lower immunogenicity profile. The safety profile of SB4 was comparable with that of ETN.

Trial registration numbers

NCT01895309, EudraCT 2012-005026-30.

Keywords: Anti-TNF, Rheumatoid Arthritis, DMARDs (biologic)

Introduction

Etanercept is a recombinant human tumour necrosis factor (TNF) receptor p75Fc fusion protein. Etanercept is well established and has been widely used in clinical practice for about 15 years, with a well-characterised pharmacological, efficacy and safety profile.1–5 Originally licensed for use in moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis (RA), the therapeutic indications have been stepwise extended and comprise treatment of patients with polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriasis and also paediatric psoriasis. Recently, etanercept has been also approved for use in non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis by the European Medicines Agency (EMA).6

A biosimilar is a biological medicinal product that contains a version of the active substance of an already authorised original biological medicinal product (reference medicinal product). A biosimilar demonstrates similarity to the reference medicinal product in terms of quality characteristics, biological activity, safety and efficacy based on a comprehensive comparability exercise.7–9

SB4 has been developed as a biosimilar to the reference product etanercept (ETN). SB4 is produced by recombinant DNA technology in Chinese hamster ovary mammalian cell expression system. Similar structural, physicochemical and biological activities of SB4 and ETN have been shown using state-of-the-art analytical methods including peptide mapping, TNF-α binding assay and TNF-α neutralisation cell-based assay. Equivalence in the pharmacokinetics (PK) between SB4 and ETN was demonstrated in a phase I study conducted in healthy male subjects.10 The objective of this study was to compare the efficacy, safety, PK and immunogenicity of SB4 and ETN in patients with RA.

Methods

Patients

Patients aged 18–75 years who have been diagnosed with RA according to the revised 1987 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria for ≥6 months and ≤15 years prior to screening were eligible for the study. Patients had to have active disease defined as ≥6 swollen and ≥6 tender joints and either erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) ≥28 mm/h or serum C reactive protein (CRP) ≥1.0 mg/dL despite methotrexate (MTX) treatment for ≥6 months (stable dose of 10–25 mg/week for ≥4 weeks prior to screening). Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and oral glucocorticoids (equivalent to ≤10 mg prednisolone) were permitted if received at a stable dose for ≥4 weeks prior to randomisation.

Major exclusion criteria consisted of previous treatment with any biological agents, history of lymphoproliferative disease, congestive heart failure (New York Heart Association Class III/IV) or demyelinating disorders, diagnosis of active tuberculosis (TB) and pregnancy or breast feeding at screening.

Additional eligibility criteria are listed in online supplementary appendix 1.

Study design

This phase III, randomised, double-blind, parallel-group study was conducted at 73 centres across 10 countries in Europe, Latin America and Asia. Patients were randomised in a 1:1 ratio to receive 50 mg of either SB4 or ETN (see online supplementary appendix 2). Patients self-administered SB4 or ETN once weekly for up to 52 weeks via subcutaneous injection. All patients had to take MTX (10–25 mg/week) and folic acid (5–10 mg/week) during the study. This study is currently ongoing, and this report represents efficacy data up to 24 weeks of treatment and safety data up to the 24-week interim report data cut-off point (21 July 2014).

Study endpoints

The primary endpoint was the ACR20 response rate at week 24. Other efficacy endpoints were the ACR50 and ACR70 responses, the numeric index of the ACR response (ACR-N), change in the disease activity score in 28 joints (DAS28) based on ESR, the area under the curve (AUC) of the ACR-N, AUC of the change in DAS28 and the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) response. Safety endpoints included incidence of adverse events (AEs) and serious adverse events (SAEs).

PK analyses were performed in the PK population, which included a subset of patients from pre-designated study sites. Key PK endpoints included serum trough concentration (Ctrough) and area under the concentration–time curve during the dosing interval (AUCτ) at steady state. Serum concentrations were determined using a validated ELISA, and PK parameters were calculated by non-compartmental analyses (WinNonlin V.5.2 or higher, Pharsight, Mountain View, California, USA).

Immunogenicity was measured in all patients. The immunogenicity endpoints were incidence of antidrug antibodies (ADAs) and neutralising antibodies (NAbs). A single-assay approach with SB4 tag was used to assess immunogenicity. ADAs were measured using validated electrochemiluminescence immunoassays, and NAbs were measured using a competitive ligand-binding assay.

Details on the serum measurement and ADA detection assay can be found in online supplementary appendix 3.

Statistical analyses

Sample size was determined using the historical data for the equivalence test. The expected ACR20 response rate at week 24 for both SB4 and ETN was expected to be 60% from the previous ETN pivotal studies.11–13 Based on the expected response rate, the equivalence margin of −15% to 15% at week 24 for ACR20 response rate was calculated in line with the US Food and Drug Administration Guidance for Industry Non-Inferiority Clinical Trials and the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use Guideline on the Choice of the Non-inferiority Margin and was also agreed with the regulatory agencies.14 15

Given a two-sided α level of 0.05 and 80% power, the two-sided 15% equivalence margin required 438 patients for the per-protocol set (PPS). Assuming 20% loss of patients from the PPS, the study required a minimum of 548 randomised patients.

The primary efficacy analysis for ACR20 response at week 24 was performed on the PPS in which patients completed week 24 visit, received 80–120% of both the expected number of study drug administrations and the expected sum of MTX doses, and did not have any major protocol deviations affecting the efficacy assessment. To declare the equivalence between the two treatment groups, the 95% CI of the adjusted treatment difference had to be entirely contained within the equivalence margin of −15% to 15%. The 95% CI of the difference of ACR20 response rates was estimated non-parametrically using the Mantel–Haenszel weights for region while adjusting for the baseline CRP. As a sensitivity analysis, the same analysis was repeated for the full analysis set (FAS) with missing data at week 24 considered as non-responses to explore the robustness of the results. Similar analyses were performed for ACR50 and ACR70 responses at week 24. Other secondary endpoints are summarised descriptively.

In addition, the exponential time–response model for ACR20 response rate was used to investigate the treatment difference during the time course of the study up to week 24.16 Details on the time–response model are provided in online supplementary appendix 4.

Safety and immunogenicity endpoints were analysed descriptively on the safety set that included all patients who received at least one dose of study drug. PK endpoints were summarised descriptively on the PK population who had at least one PK sample collected.

The analyses were performed using SAS V.9.2 software (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Results

Patient disposition and baseline characteristics

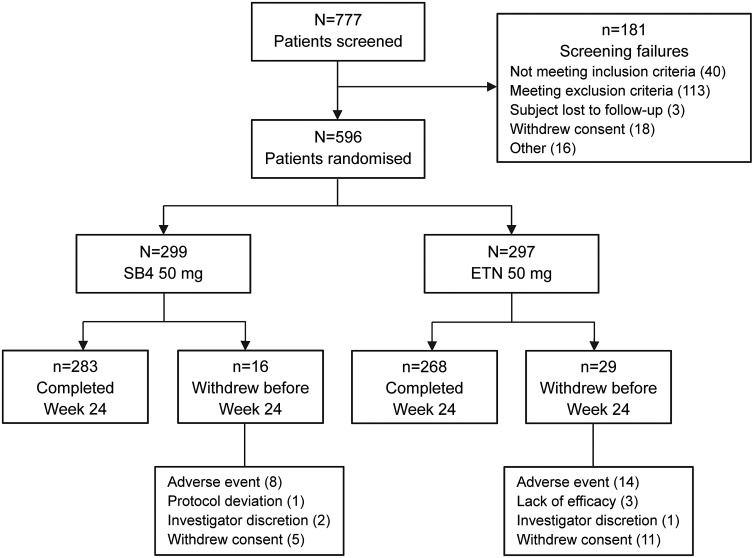

Patient screening began in June 2013, and the 24-week evaluation of the last patient occurred in April 2014. Overall, 777 patients were screened, of whom 596 patients were randomised. A total of 551 patients completed 24 weeks of treatment and 481 (80.7%) patients were included in the PPS (75 patients were excluded from the PPS due to protocol deviations, see online supplementary table S1). Patients withdrew before week 24 mainly due to AEs (3.7%) and withdrawal of consent (2.7%) (figure 1). The demographic and baseline disease characteristics were comparable between treatment groups (table 1).

Figure 1.

Summary of patient disposition. A total of 777 patients were screened and 181 patients were excluded mainly due to meeting the exclusion criteria. Multiple screening failure reasons were possible. All patients randomised were included in the full analysis set and the safety set. Of the 551 patients who completed 24 weeks of treatment, 481 patients were included in the per-protocol set. ETN, reference product etanercept.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and disease characteristics

| SB4 50 mg | ETN 50 mg | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=299 | N=297 | N=596 | ||||

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 52.1 | (11.72) | 51.6 | (11.63) | 51.8 | (11.67) |

| Age group, n (%) | ||||||

| <65 years | 253 | (84.6) | 262 | (88.2) | 515 | (86.4) |

| ≥65 years | 46 | (15.4) | 35 | (11.8) | 81 | (13.6) |

| Gender n (%) | ||||||

| Male | 50 | (16.7) | 44 | (14.8) | 94 | (15.8) |

| Female | 249 | (83.3) | 253 | (85.2) | 502 | (84.2) |

| Race, n (%) | ||||||

| White | 279 | (93.3) | 273 | (91.9) | 552 | (92.6) |

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 5 | (1.7) | 7 | (2.4) | 12 | (2.0) |

| Asian | 11 | (3.7) | 13 | (4.4) | 24 | (4.0) |

| Other | 4 | (1.3) | 4 | (1.3) | 8 | (1.3) |

| Weight (kg), mean (SD) | 72.5 | (15.93) | 71.0 | (14.63) | 71.8 | (15.30) |

| Height (cm), mean (SD) | 164.4 | (8.78) | 164.4 | (8.55) | 164.4 | (8.66) |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 26.8 | (5.51) | 26.3 | (5.30) | 26.6 | (5.41) |

| Disease duration (years), mean (SD) | 6.0 | (4.20) | 6.2 | (4.41) | 6.1 | (4.30) |

| Duration of MTX use (months), mean (SD) | 48.2 | (39.87) | 47.1 | (40.77) | 47.7 | (40.29) |

| MTX dose (mg/week), mean (SD) | 15.6 | (4.52) | 15.5 | (4.60) | 15.5 | (4.56) |

| Swollen joint count (0–66), mean (SD) | 15.4 | (7.48) | 15.0 | (7.30) | 15.2 | (7.39) |

| Tender joint count (0–68), mean (SD) | 23.5 | (11.90) | 23.6 | (12.64) | 23.5 | (12.26) |

| HAQ-DI (0–3), mean (SD) | 1.49 | (0.553) | 1.50 | (0.560) | 1.50 | (0.556) |

| Physician global assessment VAS (0–100), mean (SD) | 62.2 | (15.09) | 63.2 | (14.76) | 62.7 | (14.92) |

| Subject global assessment VAS (0–100), mean (SD) | 61.7 | (18.97) | 63.0 | (17.70) | 62.4 | (18.35) |

| Subject pain assessment VAS (0–100), mean (SD) | 61.8 | (20.22) | 62.3 | (19.22) | 62.1 | (19.71) |

| DAS28 (ESR), mean (SD) | 6.5 | (0.91) | 6.5 | (0.88) | 6.5 | (0.89) |

| C reactive protein (mg/dL), mean (SD) | 1.5 | (2.00) | 1.3 | (1.60) | 1.4 | (1.81) |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (mm/h), mean (SD) | 46.5 | (22.10) | 46.4 | (22.62) | 46.5 | (22.34) |

| Rheumatoid factor positive, n (%) | 237 | (79.3) | 231 | (77.8) | 468 | (78.5) |

BMI, body mass index; DAS28, disease activity score in 28 joints; ETN, reference product etanercept; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; HAQ-DI, Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index; MTX, methotrexate; VAS, visual analogue scale.

Efficacy

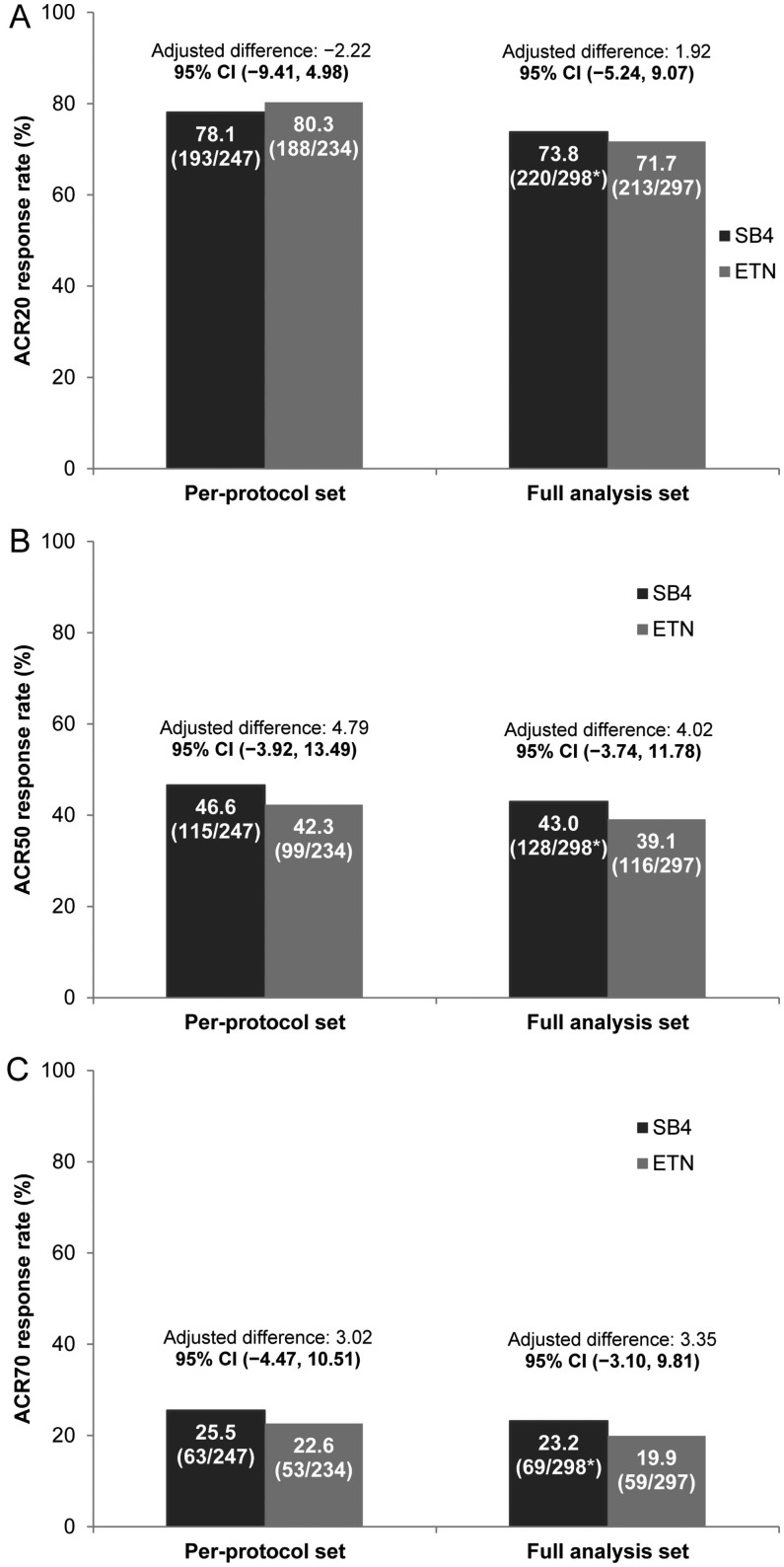

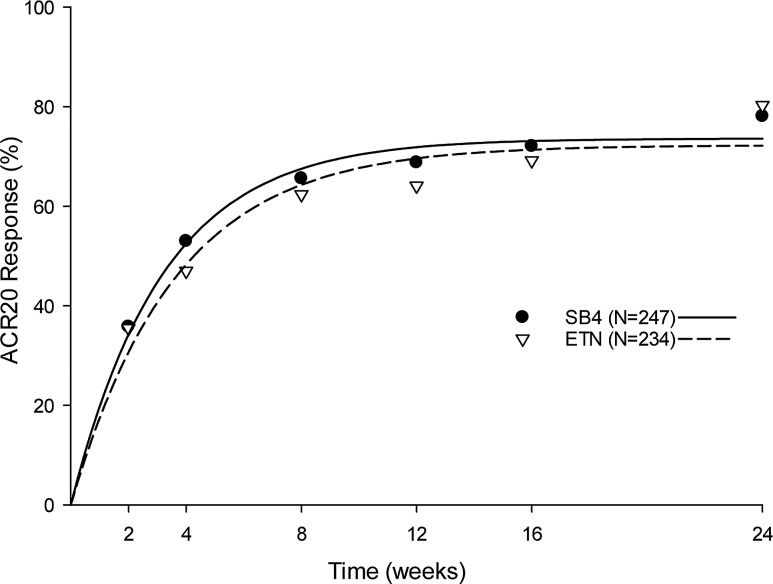

The ACR20 response rate at week 24 in the PPS was 78.1% for SB4 and 80.3% for ETN. The 95% CI of the adjusted difference (SB4—ETN) in ACR20 response rate was within the predefined equivalence margin of −15% to 15% in both the PPS (95% CI −9.41% to 4.98%) and FAS (95% CI −5.24% to 9.07%), indicating therapeutic equivalence between SB4 and ETN (figure 2). The time–response models of SB4 and ETN up to week 24 in the PPS were estimated to be equivalent since the treatment difference in terms of the two-norm difference was 12.7 and the 95% CI was −4.6 to 30.0, where the upper limit 30.0 was less than the pre-specified equivalence margin of 83.28 (figure 3).

Figure 2.

American College of Rheumatology (ACR) response rates at week 24. The adjusted treatment difference and its 95% CI were analysed with baseline C reactive protein as a covariate and stratified by region. (A) ACR 20% (ACR20) response rates of SB4 and etanercept (ETN) in the per-protocol set and full analysis set. (B) ACR50 response rates of SB4 and ETN in the per-protocol set and full analysis set. (C) ACR70 response rates of SB4 and ETN in the per-protocol set and full analysis set. *One patient from the SB4 group was excluded from the FAS due to missing efficacy data at baseline.

Figure 3.

Estimated time–response curves of American College of Rheumatology 20% (ACR20) response rate up to week 24 in the per-protocol set. For details of the estimation process, please refer to the main text. ETN, reference product etanercept.

The ACR50 and ACR70 response rates at week 24 in the PPS and FAS were equivalent between SB4 and ETN. The ACR50 response rate was 46.6% vs 42.3%, and the ACR70 response rate was 25.5% vs 22.6% in the PPS for SB4 and ETN, respectively, as shown in figure 2.

Subgroup analyses on the ACR response rates in PPS showed comparable results regardless of ADA status. The proportion of patients who achieved ACR20 response rate in patients with ADA-negative results was 78.0% in SB4 and 81.5% in ETN (95% CI −11.12% to 3.99%) (see online supplementary table S2).

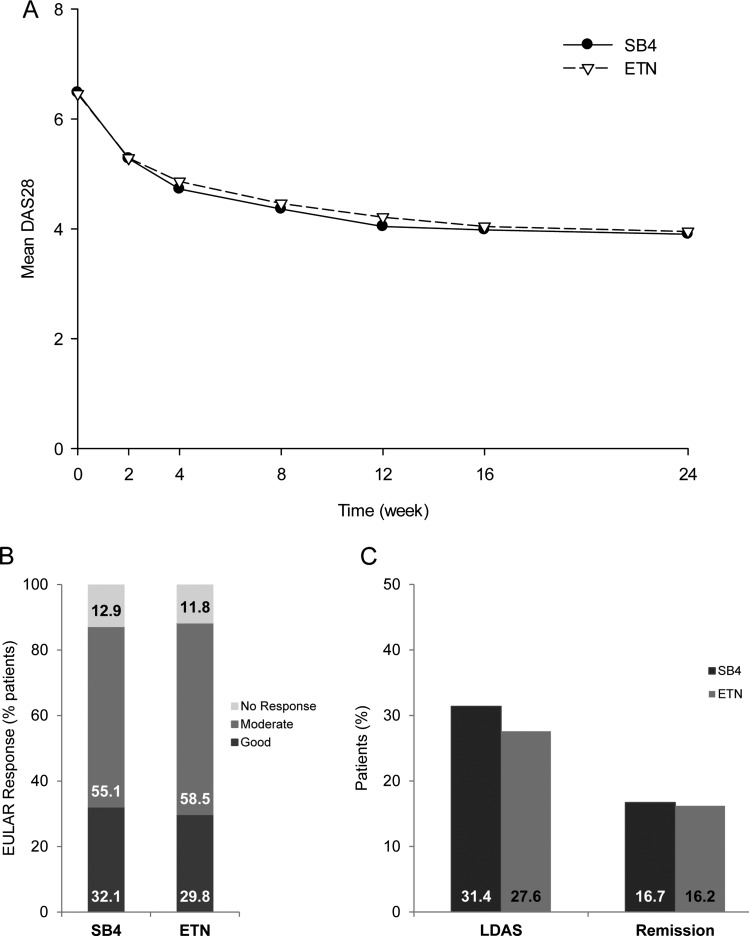

The mean improvement in DAS28 from baseline was 2.6 and 2.5 at week 24 in SB4 and ETN, respectively (95% CI −0.14 to 0.28) (figure 4A). The proportion of patients achieving good or moderate EULAR response (figure 4B), low-disease activity score or remission (figure 4C) at week 24 according to DAS28 were similar between SB4 and ETN. The ACR-N at week 24 was 45.0% in SB4 and 43.7% in ETN. The AUC of ACR-N up to week 24 (5822.2 vs 5525.0) and the AUC of change in DAS28 from baseline up to week 24 (358.3 vs 343.5) were comparable between SB4 and ETN.

Figure 4.

Changes over time in the disease activity score in 28 joints (DAS28) and European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) responses at week 24 in the full analysis set. (A) Change in DAS28 up to week 24. (B) EULAR response based on DAS28. (C) Proportion of patients achieving low-disease activity score (LDAS) defined as DAS28 ≤3.2 and remission defined as DAS28 ≤2.6. ETN, reference product etanercept.

Safety

Overall, 165 (55.2%) patients in SB4 and 173 (58.2%) patients in ETN reported at least one treatment-emergent adverse event (TEAE). Frequently occurring TEAEs by preferred term are shown in table 2, and the most frequently reported TEAE were upper respiratory tract infection (7.0%) and alanine aminotransferase increased (5.0%) in the SB4 and injection site erythema (11.1%), upper respiratory tract infection (5.1%) and nasopharyngitis (5.1%) in ETN. Most of the TEAEs were mild to moderate in severity, and TEAEs considered related to the study drug were reported in 83 (27.8%) and 106 (35.7%) patients for SB4 and ETN, respectively. Serious TEAEs were reported in 13 patients each in SB4 and ETN and 34 patients discontinued treatment due to TEAE (15 (5.0%) patients vs 19 (6.4%) patients).

Table 2.

Treatment-emergent adverse events reported in ≥2% patients by preferred term, n (%)

| Preferred term | SB4 50 mg | ETN 50 mg |

|---|---|---|

| N=299 | N=297 | |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 21 (7.0) | 15 (5.1) |

| Alanine aminotransferase increased | 15 (5.0) | 14 (4.7) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 14 (4.7) | 15 (5.1) |

| Headache | 13 (4.3) | 8 (2.7) |

| Hypertension | 10 (3.3) | 10 (3.4) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase increased | 7 (2.3) | 8 (2.7) |

| Viral infection | 7 (2.3) | 5 (1.7) |

| Injection site erythema | 6 (2.0) | 33 (11.1) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 6 (2.0) | 9 (3.0) |

| Bronchitis | 6 (2.0) | 6 (2.0) |

| Diarrhoea | 5 (1.7) | 7 (2.4) |

| Pharyngitis | 4 (1.3) | 8 (2.7) |

| Urinary tract infection | 4 (1.3) | 7 (2.4) |

| Lymphocyte count decreased | 4 (1.3) | 6 (2.0) |

| Cough | 3 (1.0) | 10 (3.4) |

| Erythema | 2 (0.7) | 10 (3.4) |

| Dizziness | 2 (0.7) | 7 (2.4) |

| Injection site rash | 2 (0.7) | 6 (2.0) |

| Injection site reaction | 1 (0.3) | 7 (2.4) |

A total of 25 patients (13 patients for SB4 and 12 patients for ETN) were diagnosed at screening with latent TB but entered the study after completing at least 30 days of treatment for latent TB and while receiving treatment. None of these patients or any other patients developed active TB during the study. Other serious infections were reported in one (0.3%) patient in SB4 and four (1.3%) patients in ETN. Malignancies were reported in three (1.0%) patients in SB4 (basal cell carcinoma, breast cancer and lung cancer metastatic) and in one (0.3%) patient in ETN (invasive ductal breast carcinoma).

Injection site reactions (ISRs), counted by the high-level group term of administration site reactions, occurred in fewer patients in SB4 compared with ETN. There were 22 ISRs reported in 11 (3.7%) patients vs 156 ISRs reported in 51 (17.2%) patients in SB4 and ETN, respectively (p<0.001). Most of the ISRs occurred early (between weeks 2 and 8) and were mild in severity. The incidence of ISR for SB4 and ETN were 3.7% vs 17.1% in ADA-negative patients and 0.0% vs 17.9% in ADA-positive patients, respectively (see online supplementary table S3).

One death was reported in the SB4 treatment group due to cardiorespiratory failure, which was not considered related to the study drug.

Pharmacokinetics

PK analyses were performed on 79 patients (41 patients in SB4 and 38 patients in ETN).

Ctrough were comparable at each time point between SB4 (ranging from 2.419 to 2.886 μg/mL in weeks 2–24) and ETN (ranging from 2.066 to 2.635 μg/mL in weeks 2–24) (see online supplementary figure S2). The AUCτ at week 8 was 676.4 vs 520.9 μg h/mL and the inter-subject variability (CV%) was 37.7% vs 50.1% in SB4 and ETN, respectively (see online supplementary figure S3).

Immunogenicity

The incidence of ADA was significantly lower in SB4 compared with ETN. Two (0.7%) patients in SB4 and 39 (13.1%) patients in ETN tested positive at least once up to week 24 (p<0.001), and only one sample from the ETN group had neutralising capacity. The ADAs appeared early (between weeks 2 and 8), and most of the ADAs disappeared after week 12 (see online supplementary appendix 9).

Discussion

In this randomised, double-blind, parallel-group, multicentre study, the efficacy, safety, PK and immunogenicity of SB4 were compared with those of ETN in patients with moderate to severe RA despite MTX treatment. Equivalence of efficacy between SB4 and ETN was demonstrated and the safety of SB4 was generally comparable to ETN.

The primary endpoint at week 24 was met: the 95% CI of the adjusted treatment difference between SB4 and ETN in ACR20 response rate was within the predefined equivalence margin of −15% to 15%. The ACR20 responses observed in this study (73.8% for SB4 and 71.7% for ETN in FAS) were within the range of ACR20 response rates reported in pivotal studies with ETN (49–86%)4 11–13 17–19 but slightly higher than what was assumed (60%). Since active treatment is used in both groups, biosimilar studies tend to show higher ACR20 response rates20–22 compared with pivotal controlled studies.

As the primary efficacy assessment (ACR20 response at week 24) was evaluated at a time point in the therapeutic plateau, various efficacy endpoints and statistical methods were applied to detect any non-equivalence in efficacy and to support the robustness of the primary efficacy analysis. The ACR20 response rate, ACR-N and DAS28 were measured at several different time points early in the treatment period. The time–response curves of SB4 and ETN up to week 24 showing the ACR20 response over time were estimated to be equivalent, and the AUC of ACR-N up to week 24 and AUC of the change in DAS28 (ESR) from baseline up to week 24 were comparable between SB4 and ETN, indicating that the efficacy of SB4 over time was similar to ETN.

Overall, the safety profile of SB4 was comparable with that of ETN and was similar to those observed in the pivotal trials with ETN. There were no cases of active TB and only one patient in SB4 and four patients in ETN reported serious infection, which is lower than 6.3% shown in ETN product information.6 Malignancies were reported in three (1.0%) patients in SB4 and one (0.3%) patient in ETN. The incidence of malignancy observed in this study is similar to the previously conducted studies.4 23 24 Interestingly, ISRs were reported in fewer patients from SB4 compared with ETN (3.7% vs 17.2%). The proportion of patients who experienced at least one ISR from ETN group in this study (17.2%) is in line with recently conducted studies with 50 mg once weekly ETN,13 and most ISRs occurred in the first month, which is in accordance with the reference product label.6 26 Although it is unclear why the incidence of ISR was lower in SB4 compared with ETN, the difference in drug product formulation and container closure system may have contributed to the lower ISR. The only difference in drug composition between SB4 and ETN is the absence of L-arginine in SB4. It has not been shown that L-arginine is associated with increased risk of ISR; however, we cannot preclude the sole difference in formulation (absence of L-arginine) as the cause of ISR. In addition, natural rubber latex known to cause hypersensitivity reactions has not been used in the needle shield of SB4. There appears to be no correlation between ISR and ADA development, which is consistent with previously conducted studies.25

In this study, Ctrough and steady state PK was investigated in a subset of population to provide supporting evidence to the phase I comparative PK study in healthy subjects, which demonstrated similar PK behaviour. In the phase III study, the Ctrough values were comparable between SB4 and ETN at each time point and AUCτ at steady state was relatively higher in SB4 compared with ETN; however, the numerical difference is likely due to an inherent high inter-subject variability (37.7% vs 50.1%).

The incidence of ADA shown in the ETN group of this study (13.1%) is seemingly higher compared with what has been reported in the previous studies.6 In this study, the assay used to detect immunogenicity was more sensitive and immunogenicity was measured more frequently; most of the ADAs were detected at week 4 in this study while immunogenicity was not measured at these time points in the previous studies and could have resulted in higher overall incidence of ADA in this study.13 25 27 The characteristics of antibodies detected in this study were generally transient and non-neutralising, which is in accordance with those established with ETN in previous studies.6 25 Since SB4 tagged single-assay approach was used to detect immunogenicity, the assay method does not seem to have caused the lower incidence of ADA observed in SB4 compared with ETN (0.7% vs 13.1%). There are product-specific factors known to affect immunogenicity, such as product origin (foreign or human), product aggregates, impurities, container closure system;28–31 however, factors contributing to lower immunogenicity of SB4 are to be further investigated. Yet, according to the EMA guideline on biosimilars7 the lower immunogenicity of SB4 does not preclude classification as biosimilar since clinical efficacy of SB4 and ETN were equivalent in patients with ADA-negative results and no apparent correlation between ADA and clinical response or safety was observed.7 25 32 33

To date, this is the first global, multicentre study comparing an ETN biosimilar to reference product ETN. Confirmed equivalence of SB4 and ETN in this study may provide an alternative treatment option for RA and allow better access to biologics for patients.

Conclusions

SB4 was shown to be equivalent in terms of clinical efficacy when compared with ETN. SB4 was well tolerated with a comparable safety profile to ETN.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients who were involved in this study, the study personnel who made this work possible and the study investigators: Bulgaria: Goranov I, Geneva-Popova M, Shimbova K, Mihaylova M, Nestorova R, Stoilov R, Todorov S, Dimitrov E; Colombia: Vargas F, Londoño J; Czech Republic: Podrazilova L, Mosterova Z, Sedlackova M, Simkova G, Brabcova H, Urbanova Z, Kopackova J, Vitek P, Stejfova Z; Hungary: Nagy M, Sulyok G, Kranicz A, Sillo A, Simoncsics E; Republic of Korea: Choe J, Lee S, Lee S, Kang S, Bae S, Kim J; Lithuania: Lietuvininkiene V, Kausiene R, Stropuviene S, Kriauciuniene V; Mexico: Garcia de la Torre I; Poland: Janecka I, Rychlewska-Hanczewska A, Lis-Studniarska D, Zielinska A, Daniluk S, Hilt J, Glogowska-Szelag J, Kolczewska A, Sliwowska B, Rell-Bakalarsk M, Grabowicz-Waśko B, Marcinkiewicz J, Ruzga Z, Hajduk-Kubacka S; Ukraine: Ignatenko G, Vatutin M, Gasanov Y, Gnylorybov A, Shevchuk S, Rekalov D, Povoroznyuk V, Yatsyshyn R, Petrov A, Stanislavchuk M; UK: Haigh R. The authors also thank the study team for assistance with the logistic management and reporting of the study, specifically Ilsun Hong (lead clinical study manager) and Evelyn Eubene Hong (scientific solutions for writing and editorial support).

Footnotes

Correction notice: This article has been corrected since it was published Online First. Several minor textual changes have been made and the author affiliations altered.

Contributors: PE, JG and SYC were involved in the conception or design of the work, or the acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data, drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. JV, AS, PL, WP, AB, VT, VZ, BS, RM and AB were involved in acquisition of data, drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and final approval of the version published.

Funding: This study was funded by Samsung Bioepis Co., Ltd.

Competing interests: All authors received funding for clinical research from Samsung Bioepis: PE received consulting fees; JV, AS, PL, WP, AB, VT, VMZ, BS, RM, and AABR received research grants; SYC and JG are full-time employee of Samsung Bioepis. In addition, PE reports receiving grant/research support from AbbVie, Pfizer and consultancy fee from AbbVie, BMS, Pfizer, USB, MSD, Roche, Novartis, Takeda, Lilly; JV served on speakers bureau for USB, Pfizer, AbbVie, MSD; PL reports receiving grant/research support from Roche, MSD, Janssen, Novo-Nordisk, UCB, Pfizer, Novartis, GSK, BM, served as paid instructor for Novo-Nordisk, and served on speakers bureau for MSD, UCB, Roche, Amgen; AB reports receiving grant/research support from AbbVie.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: This study was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice Guidelines established by the International Conference Harmonisation. The protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board or the independent ethics committee of each investigational centre.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Murray KM, Dahl SL. Recombinant human tumor necrosis factor receptor (p75) Fc fusion protein (TNFR:Fc) in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Pharmacother 1997;31:1335–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goffe B, Cather JC. Etanercept: An overview. J Am Acad Dermatol 2003;49(2 Suppl):S105–11. 10.1016/mjd.2003.554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fuchs BS, Hadi S. Use of etanercept in the treatment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Rev Recent Clin Trials 2006;1:259–63. 10.2174/157488706778250131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Emery P, Breedveld FC, Hall S, et al. Comparison of methotrexate monotherapy with a combination of methotrexate and etanercept in active, early, moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis (COMET): a randomised, double-blind, parallel treatment trial. Lancet 2008;372:375–82. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61000-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Emery P, Hammoudeh M, FitzGerald O, et al. Sustained remission with etanercept tapering in early rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 2014;371:1781–92. 10.1056/NEJMoa1316133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Enbrel Summary of Product Characteristics. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/000262/WC500027361.pdf (27 Feb 2015).

- 7.European Medicines Agency. Guideline on similar biological medicinal products containing biotechnology-derived proteins as active substance: non-clinical and clinical issues. (EMEA/CHMP/BMWP/42832/2005). 22 February 2006. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2009/09/WC500003920.pdf (27 Feb 2015).

- 8.Kay J. Biosimilars: a regulatory perspective from America. Arthritis Res Ther 2011;13:112 10.1186/ar3310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dorner T, Strand V, Castaneda-Hernandez G, et al. The role of biosimilars in the treatment of rheumatic diseases. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:322–8. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee YJ, Shin D, Kim Y, et al. A Phase I pharmacokinetic study comparing SB4, an etanercept biosimilar, and etanercept reference product (Enbrel®) in healthy male subjects. EULAR Congress; 2015; Rome, Italy: European League Against Rheumatism; SAT0176 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weinblatt ME, Kremer JM, Bankhurst AD, et al. A trial of etanercept, a recombinant tumor necrosis factor receptor:Fc fusion protein, in patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving methotrexate. N Engl J Med 1999;340:253–9. 10.1056/NEJM199901283400401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Combe B, Codreanu C, Fiocco U, et al. Etanercept and sulfasalazine, alone and combined, in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis despite receiving sulfasalazine: a double-blind comparison. Ann Rheum Dis 2006;65:1357–62. 10.1136/ard.2005.049650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keystone EC, Schiff MH, Kremer JM, et al. Once-weekly administration of 50 mg etanercept in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 2004;50:353–63. 10.1002/art.20019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.US Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry: Non-inferiority clinical trials. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/Guidances/UCM202140.pdf (27 Feb 2015).

- 15.Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP). Guideline on the choice of the non-inferiority margin. (EMEA/CPMP/EWP/2158/99). 27 July 2005. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2009/09/WC500003636.pdf (27 Feb 2015). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Reeve R, Pang L, Ferguson B, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis disease progression modeling. Ther Innov Regul Sci 2013;47:641–50. 10.1177/2168479013499571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klareskog L, van der Heijde D, de Jager JP, et al. Therapeutic effect of the combination of etanercept and methotrexate compared with each treatment alone in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: double-blind randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2004;363:675–81. 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15640-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bathon JM, Martin RW, Fleischmann RM, et al. A comparison of etanercept and methotrexate in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 2000;343:1586–93. 10.1056/NEJM200011303432201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moreland LW, Schiff MH, Baumgartner SW, et al. Etanercept therapy in rheumatoid arthritis. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 1999;130:478–86. 10.7326/0003-4819-130-6-199903160-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kay JC, Chandrashekara A, Olakkengil S, et al. A phase 3, randomized, double-blind, active comparator study of the efficacy and safety of BOW015, a biosimilar infliximab, in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis on stable methotrexate doses. EULAR Congress; 2014; Paris, France: OP0012. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoo DH, Piotrowski P, Ramiterre M, et al. A randomized, double-blind, phase 3 study demonstrates clinical equivalence of CT-P13 to infliximab when co-administered with methotrexate in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. EULAR Congress; 2012; Berlin, Germany: FRI0143. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bae SC, Choe JS, Park JY, et al. A randomized, double-blind, phase 3 equivalence trial comparing the etanercept biosimilar, HD2013, with Enbrel®, in combination with methotrexate (MTX) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). EULAR Congress; 2014; Paris, France: OP0011. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lopez-Olivo MA, Tayar JH, Martinez-Lopez JA, et al. Risk of malignancies in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with biologic therapy: a meta-analysis. Jama 2012;308:898–908. 10.1001/2012.jama.10857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Combe B, Codreanu C, Fiocco U, et al. Efficacy, safety and patient-reported outcomes of combination etanercept and sulfasalazine versus etanercept alone in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a double-blind randomised 2-year study. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:1146–52. 10.1136/ard.2007.087106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dore RK, Mathews S, Schechtman J, et al. The immunogenicity, safety, and efficacy of etanercept liquid administered once weekly in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2007;25:40–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zeltser R, Valle L, Tanck C, et al. Clinical, histological, and immunophenotypic characteristics of injection site reactions associated with etanercept: a recombinant tumor necrosis factor alpha receptor: Fc fusion protein. Arch Dermatol 2001;137:893–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Genovese MC, Bathon JM, Martin RW, et al. Etanercept versus methotrexate in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis: two-year radiographic and clinical outcomes. Arthritis Rheum 2002;46:1443–50. 10.1002/art.10308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Singh SK. Impact of product-related factors on immunogenicity of biotherapeutics. J Pharm Sci 2011;100:354–87. 10.1002/jps.22276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hermeling S, Crommelin DJ, Schellekens H, et al. Structure-immunogenicity relationships of therapeutic proteins. Pharm Res 2004;21:897–903. 10.1023/B:PHAM.0000029275.41323.a6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosenberg AS. Effects of protein aggregates: an immunologic perspective. Aaps j 2006;8:E501–7. 10.1208/aapsj080359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.US Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry: Immunogenicity assessment for therapeutic protein products. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/guidancecomplianceregulatoryinformation/guidances/ucm338856.pdf (27 Feb 2015).

- 32.Jamnitski A, Krieckaert CL, Nurmohamed MT, et al. Patients non-responding to etanercept obtain lower etanercept concentrations compared with responding patients. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:88–91. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Keystone E, Freundlich B, Schiff M, et al. Patients with moderate rheumatoid arthritis (RA) achieve better disease activity states with etanercept treatment than patients with severe RA. J Rheumatol 2009;36:522–31. 10.3899/jrheum.080663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.