Abstract

Critical illnesses and injuries are recognized as major threats to human health, and they are usually accompanied by uncontrolled inflammation and dysfunction of immune response. The alpha 7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (α7nAchR), which is a primary receptor of cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway (CAP), exhibits great benefits for critical ill conditions. It is composed of 5 identical α7 subunits that form a central pore with high permeability for calcium. This putative structure is closely associated with its functional states. Activated α7nAChR exhibits extensive anti-inflammatory and immune modulatory reactions, including lowered pro-inflammatory cytokines levels, decreased expressions of chemokines as well as adhesion molecules, and altered differentiation and activation of immune cells, which are important in maintaining immune homeostasis. Well understanding of the effects and mechanisms of α7nAChR will be of great value in exploring effective targets for treating critical diseases.

Keywords: alpha 7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor, critical illness, cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway, neuroinflammation, immune function, protective effect.

Introduction

Critical illnesses are known as great threats to human health, which initiate abnormal response to insults and infections, and manifest uncontrollable inflammation and dysfunction of immune cells. Recently, the neuroendocrine-immune networks show great benefits for improving severe diseases 1. For instance, the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway (CAP), which is composed of efferent vagus nerve, acetylcholine and α7 subunit of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (α7nAchR), has been reported to attenuate excessive inflammation in critical settings 2-7. Activated by peripheral or central stimuli, the brain cholinergic neurons deliver the information to efferent vagus nerves which innervate peripheral organs and release acetylcholine that can inhibit the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines by interacting with α7nAchR on inflammatory cells 1, 8, 9.

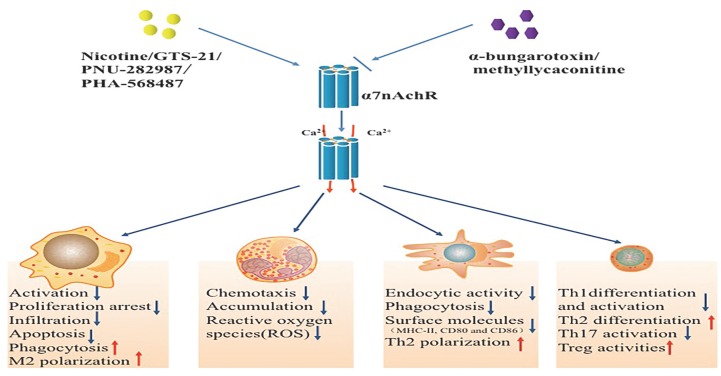

α7nAchR is a major receptor of CAP, and first discovered expression on neurons. It has been well-studied as a pharmacological target for neuropathological diseases, underlying a neuroprotective role of α7nAchR 10. Activation of α7nAchR with GTS-21 or AQW051 significantly mitigated the severity of psychotic disorders by improving cognition, learning and working memory 11, 12. Recently, numerous studies showed that it widely distributed around non-neuronal cells including endothelial cells, macrophages, dendritic cells (DCs), and keratinocytes 13-15, and activating α7nAchR effectively diminished the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and restored disturbed function of immune cells (Fig. 1)16, 17. In α7nAchR-deficient mice, however, activation of cholinergic system failed to effectively attenuate the excessive inflammation or improve survival rates in critical conditions 14, 18, Thus, the α7nAchR might be an effective therapeutic target for inhibiting excessive inflammation and modulating immune homeostasis. Extensive works, focused on exploring effective drugs for activating cholinergic system, have identified that administration of α7nAchR agonists showed distinct benefits for severe illnesses 19, 20. However, its specific molecular mechanisms remained unclear. In this review, we attempt to summarize the current molecular mechanisms concerning protective effects of α7nAchR on acute critical illnesses and provide theoretic basis for seeking novel interventional strategies.

Figure 1.

Effects of activated alpha 7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (α7nAchR) on immune cells. The α7nAchR has been identified to be expressed on multiple immune cells such as macrophages, neutrophils, dendritic cells, and T lymphocytes. The classic α7nAchR is a homomeric pentamer composed of five putatively identical α7 subunits that form a central pore with high permeability for calcium. Nicotine, GTS-21 and PNU-282987 are typical agonists of α7nAchR which can activate α7nAchR followed by transient Ca2+ influx. Activated α7nAchR can affect the function of immune cells while abated by α7nAchR antagonists including α-bungarotoxin and methyllycaconitine.

The structure and the function of α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor

The groups of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors are ligand-gated ion channels by the combination of at least 17 different subunits that are organized as hetero- or homo-pentamers 21. The function of each subunit varies with diverse constructions, for instance, β subunits show lower affinity for acetylcholine than α subunits 22. Therefore, diverse combinations of protein subunits may provide considerable functional variation in the development of receptor subtypes. For example, α4β2 receptors, another important target for modulating neurological functions, manifest different effects on neurodegenerative diseases with different combinations. They show high affinity for Ach with construction of (α4) 2(β2) 3, while (α4) 3(β2) 2 receptors express low affinity for binding Ach. Other forms of nAchRs, such as α3β2 and α3β4 receptors, are also reported quite different roles in clinical trials 23, 24. The classic α7nAchR is composed of five identical α7 subunits which form a central pore with high permeability for calcium 13, 25, Its structural unicity may contribute to functional uniqueness and rapid response to multiple agonists. These agonists that involve both orthosteric and allosteric modulators can regulate α7nAchR expression and activation after effective binding 26. It has been reported that agonists could act as molecular chaperones to induce upregulation and maturation of α7nAchR, which might not be seen in transcriptional levels. Additionally, agonists induced α7nAchR activation were identified to be associated with proteins conformation changes characterized by the opening of transmembrane calcium channels 27. Therefore, the functional states of α7nAchR changed rapidly and were associated with Ca2+ influx: in rest state, the gate was closed and prevented ion flux through the channel, while it transformed into the desensitized states after a transient Ca2+ influx upon activation 28-30. Additionally, the desensitized states of α7nAchR were reported to happen quickly after binding with agonists, which were associated with different types and function time of agonists, mutations of residues and interactions among various linkers 31,32, indicating that the α7nAchR was initiated early after the onset of inflammation and the functional states of α7nAchR might be maintained in a certain range by self-regulation.

Stimulation of macrophages with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or pro-inflammatory cytokines also markedly up-regulated the expression of α7nAchR. Similar results were obtained when endothelium of rat kidney endured ischemia-reperfusion injury 13, 33. Early administration of nicotine or GTS-21 significantly ameliorated ischemia-reperfusion injury of rat kidney and improved survival of burned mice 33, 34, suggesting early initiation of α7nAchR in critical settings.

Selective activation of α7nAchR can benefit many critical conditions (Table 1) 19, 20, 35-38. Recently, a number of investigations have focused on exploring effective agonists and determining downstream signaling pathway when α7nAchR was activated. Nuclear translocation of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) was a key regulatory factor in modulating activation of immune cells and expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines 39. Activation of α7nAchR significantly decreased NF-κB activity, followed by lowered inflammatory response 40. Further investigations showed that there were various signaling pathways that contributed to inhibiting NF-κB activity after α7nAchR activated 40, 41. In the remaining part of this review, we will focus on discussing the association between α7nAchR activation and development of acute critical illnesses, including underlying mechanisms regarding the protective roles of α7nAchR.

Table 1.

The protective effects of α7nAchR activation on critical illnesses

| Types of critical illnesses | Effects of α7nAchR | References |

|---|---|---|

| Severe burns/trauma | ▲Protecting against cell death ▲Limiting neutrophil priming ▲Preventing gut barrier failure ▲Attenuating local and systemic inflammation ▲Ameliorating organ injury ▲Improving survival rate |

30, 35, 43, 47, 49 |

| Sepsis | ▲Enhancing bacterial clearance ▲Down-regulating the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokine ▲Decreasing chemokine production ▲Inhibiting neutrophil migration ▲Preventing systemic inflammation ▲Ameliorating organ injury ▲Improving survival rate |

14, 15, 54, 55, 56 |

| Acute lung injury | ▲Alleviating lung edema ▲Inhibiting TNF-α release ▲Lowering gradient of pulmonary alveoli-artery ▲Reducing neutrophil accumulation ▲Decreasing pulmonary apoptosis ▲Maintaining integrity of pulmonary endothelium ▲Improving the outcome |

7, 62, 63, 64, 65 |

| Ischemia-reperfusion injury | ▲Reducing serum TNF-α and HMGB1 levels ▲Improving renal function ▲Attenuating tubular cells necrosis ▲Decreasing infarct volume ▲Elevating neurological manifestation ▲Reducing neutrophil infiltration ▲Suppressing superoxide radical generation ▲Reducing oxidative stress ▲Inhibiting systemic inflammatory response |

31, 73, 74, 75, 76 |

| Acute pancreatitis | ▲Inhibiting infiltration of pancreatic neutrophils ▲Reducing plasma TNF-α and IL-6 concentrations ▲Decreasing plasma amylase and lipase levels ▲Alleviating severity of experimental pancreatitis |

5, 18 |

α7nAchR: Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor alpha7; TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor-a;

HMGB-1: High mobility group box-1 protein; IL-6: Interleukin-6.

The protective effect of α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor activation on critical illnesses

Severe trauma/burns

Severe trauma is characterized by extensive local and systemic inflammation owing to direct mechanical insults, and subsequently induce disturbed immune response and multi-organ failure 42. Serious burn injury can also bring about septic complications with multiple micro-organisms by damaging mechanical barrier and bacterial contamination 43, 44. Therefore, restoration of mechanical barrier and inhibition of excessive inflammatory response are major interventional measures.

In experimental models of traumatic brain injury (TBI), the contents of brain α7nAchR were significantly lowered 45. However, expressions of α7nAchR in macrophages and myofibroblasts were up-regulated during the healing stage of skeletal muscle injury, which was also shown in buccal mucosal cells of burn patients 46, 47, suggesting that the expressions of α7nAchR varied with different pathological conditions and provided by different therapeutic effects. It has been reported that nicotine or GTS-21 utilization could significantly attenuate cognitive dysfunction following experimental TBI and improve burned mice survival by attenuating local and systemic inflammation 33, 48. And treatment with nicotine could also protect gut barrier through up-regulating the expression of occludin and ZO-1 which were proteins contributing to cellular tight junctions 36.

Septic complications

Sepsis is defined as disturbed responses to multiple infection with its severity driven by the excessive inflammation 49,50. However, simply antagonization of pro-inflammatory cytokines showed low efficiency in improving septic survival 51, suggesting that the complicated networks of inflammation might be responsible for its high mortality.

Cedillo and colleagues made a comparison of α7nAchR mRNA levels in peripheral blood monocytes between 33 controls and 33 septic patients, and found that α7nAchR mRNA levels in septic patients were markedly elevated, which returned to controlled levels after recovery 52. In addition, α7nAchR levels were considered to be inversely associated with the magnitude of severity and mortality rate in severe septic patients 52, Activation of α7nAchR by GTS-21 significantly improved survival in septic models, but it failed by antagonizing α7nAchR or gene knockdown 16, 17. Further researches showed that stimulation of α7nAchR alleviated inflammatory response of macrophages 53, and attenuated sepsis-induced acute lung injury by inhibiting chemokines production and neutrophils migration 54, 55. Additionally, α7nAchR activation showed benefits for septic conditions by improving bacterial clearance of macrophages 54, 55.

Acute lung injury

ALI is a complication mainly initiated by severe infection, trauma and burns, and it is often followed by acute respiratory failure 56, 57. ALI is characterized by pulmonary edema, alveolocapillary lesion, and respiratory injury owing to uncontrolled local inflammation 58-60. Therefore, regulation of the networks of local inflammation may be of great therapeutic value. Pretreatment or delayed administration of nicotine significantly alleviated pathological changes and lung edema in LPS induced ALI models, followed by marked improvement of outcome 61. GTS-21 also improved lung function in ALI conditions by inhibiting TNF-α production, while these effects were vanished with α7nAChR antagonist mecamylamine 62. On the contrary, a deficiency of α7nAchR showed a two-fold increase of pulmonary permeability and volume of lung water, thus suggesting the therapeutic interest of α7nAchR in ALI 7, 62. Further researches have documented that α7nAchR could benefit ALI models by lowering alveoli-artery gradient, reducing neutrophils accumulation and pulmonary apoptosis 61-63. Additionally, maintaining the integrity of pulmonary endothelium also appeared to be the effects of α7nAchR activation 36, 64.

Ischemia-reperfusion injury

Ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI) is a distinct clinical manifestation and affects many organs such as brain, heart, liver, kidney, and intestine 65-68. Initiated by ischemic injury, it enhances the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and causes calcium overload of intracellular and endothelial cells damage 69. Subsequent reperfusion stages, however, are characterized by exacerbated tissue injury, uncontrolled systemic inflammation, and multi-organ failure 69. Accordingly, removal of ROS, alleviation of inflammatory response, and inhibition of cells apoptosis are major interventions 70.

Pretreatment with nicotine or GTS-21 significantly protected tubular cells from necrosis and restored renal function in rats after IRI 34, 71. Likewise, administration of PHA-543613 decreased infarct volume and improved cognition in cerebral IRI, while opposite effects were found by giving α7nAchR blocker α-bungarotoxin 72. Therefore, the protective roles of α7nAChR in IRI could be applied to different organs. Activation of α7nAChR significantly suppressed serum TNF-α and HMGB1 levels during myocardial IRI and resulted in reduction of neutrophils accumulation and attenuation of tubular damage in renal IRI by preventing tubular cells necrosis and myeloperoxidase activity73. However, these effects were not significant in delayed treatment, suggesting that α7nAChR might function in the early stages of IRI conditions 71.

Acute pancreatitis

Acute pancreatitis is a serious ailment with etiologic factors involving gallstones, alcohol, infection and so on 74. Pancreatic auto-digestion induced by activation of trypsinogen is believed a major factor in the pathogenesis of pancreatitis 75. Recent evidences have indicated that inflammatory disorder also accounted for its initiation and aggravation 76, 77. The production of cytokines and chemokines, such as TNF-α, IL-6, monocyte chemotactic protein (MCP)-1, and intracellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) were significantly enhanced in acute pancreatitis, and they were independent of trypsinogen activation 77, 78. Also, infiltration of neutrophils and macrophages were reported to act as key factors in the development of acute pancreatitis with relevant to disease severity. T cells' dysfunction, likewise, accounted for the progression of acute pancreatitis 77. However, mechanisms underlying the pathogenesis and progress of acute pancreatitis were on elucidated. van Westerloo et al. found that GTS-21 significantly alleviated the severity of experimental pancreatitis by lowering plasma amylase and lipase levels 20. Less infiltration of neutrophils and low IL-6 concentrations were also noticed in acute pancreatitis preceded by GTS-21 treatment 20. Furthermore, melanocortin peptides exerted protective effects in acute pancreatitis as shown by blunted plasma amylase and lipase activity, decreased TNF-α and IL-6 levels, and reduced neutrophils accumulation, which were also associated with activating cholinergic system 5.

Molecular mechanisms of α7nAChR action

α7nAChR and inflammation

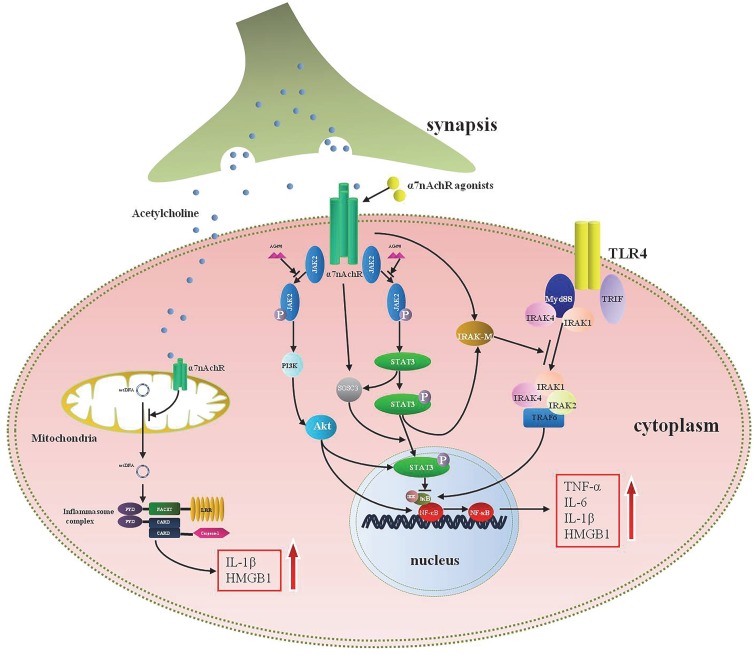

Interactions between α7nAChR and pro-inflammatory cytokines involve numerous molecular pathways (Fig. 2). Selective activation of α7nAChR has been identified to down-regulate pro-inflammatory cytokines expressions 1.Additionally, pro-inflammatory cytokines, HMGB1 as an example, could markedly up-regulate the expression of α7nAChR 13, suggesting that there might be bilateral interactions between α7nAChR and inflammatory mediators. Clinical studies have also reported negative correlation between concentrations of α7nAChR agonists and pro-inflammatory mediators' levels 79.

Figure 2.

The intracellular signaling pathways of α7nAchR in anti-inflammatory response. Acetylcholine (Ach), released from the terminal of synapsis, is a primary endogenous agonist of α7nAchR and exerts anti-inflammatory effect by activating α7nAchR. Activated cytomembrane α7nAchR inhibits the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines mainly through blocking nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) activity, which may involve multiple intracellular cascades. Janus kinase 2 (JAK2)-signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) pathway represent a typical anti-inflammatory cascade for α7nAchR which can be blocked by AG490, a selective antagonist of JAK2. Phosphorylated STAT3 suppresses the dissociation between IκB and NF-κB, and subsequently inhibits the activation of NF-κB. Activated STAT3 also up-regulates the expression of suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 (SOCS3) and interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase M (IRAK-M), both are essential for anti-inflammatory reaction. IRAK-M can negatively regulate Toll-like receptor (TLR) activity by preventing the dissociation of active IRAKs (IRAK-1 and IRAK-4) from MyD88 and subsequently bonding with TNF receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6), thus it can interfere active TLR downstream signalings and inhibit the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Synergistically, PI3K-Akt pathway can attenuate the pro-inflammatory cytokine production when activated by α7nAchR agonists. Mitochondria are reported to express α7nAchR. Intra-cellular acetylcholine can inhibit production of IL-1β and HMGB1 by suppressing release of mitochondrial DNA and inhibiting activation of NACHT, LRR and PYD domains-containing protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome.

Wang et al. found that activation of α7nAChR could significantly block NF-κB signaling 32. Various mechanisms were involved in interfering with NF-κB activation. For instance, α7nAChR-Janus kinase 2 (JAK2)-signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3)-NF-κB cascades were the most studied, which significantly suppressed activity of NF-κB after α7nAChR activation 41, 80. Blocking JAK2 with AG490, a selective antagonist of JAK2 phosphorylation, dampened the inflammatory regulating effects of α7nAChR agonists, same effects were exhibited by inhibiting STAT3 phosphorylation 80, indicating that JAK2-STAT3 might function as pivotal bridge between α7nAChR and NF-κB regulation. IκB, which was recognized as a key regulator of NF-κB, prevented the NF-κB activation in resting state 81. It dissociated from NF-κB after being activated by pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), and subsequently induced NF-κB translocation 82. Administration of nicotine to monocytes resulted in suppressed ubiquitination of IκB and further inhibited activity of NF-κB by depressing IκB kinases (IKK) activity 40. Other associated mechanisms included Myeloid differentiation factor 88 (MyD88) that was a key intra-cellular reactive protein for Toll-like receptor (TLR) and acted as an universal adapter for TLRs, including TLR2, TLR4, TLR5, TLR7, and TLR9. Studies have shown that MyD88 could activate IKK and further induce NF-κB translocation upon activation 83. MyD88 expression was increased when exposed to LPS, while nicotine decreased the expression of MyD88, and subsequently interfered NF-κB transcription 84. Similar effects were demonstrated in HBE16 cells transfected with MyD88 siRNA, suggesting that MyD88 was a potential target for α7nAChR with regulating cytokines profiles 84.

Other than controlling acute inflammation by inhibiting NF-κB activity, a number of negative regulatory factors are also recognized concerning with α7nAChR downstream pathways. Interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase M (IRAK-M) belongs to the IRAK family but with kinase activity absent, which is widely expressed in monocytes and macrophages 85. IRAK-M expression is a negative regulator of TLR activity through preventing the dissociation of active IRAKs (IRAK-1 and IRAK-4) from MyD88, and it can interfere active TLRs downstream signalings by binding with TNF receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6)86. Maldifassi and colleagues have proved that nicotine enhanced IRAK-M expression at both gene and protein levels in macrophages by activating JAK2/STAT3 or PI3K/STAT3 cascade, resulted in decreased production of TNF-α 87. Silencing IRAK-M gene significantly reversed the anti-inflammatory effects of nicotine 87. Other signals involved in the anti-inflammatory mechanisms of α7nAChR were also present effectively. Taking PI3K-Akt pathway for example, activity of PI3K-Akt was significantly enhanced after treatment with donepezil that could activate α7nAChR, followed by alleviatived neuro-inflammation 88. In addition, activation of α7nAChR distinctly diminished TLR4 expression via increasing PI3K/Akt activation, thereby leading to reduction of inflammatory cytokines and improvement of sepsis survival 89. α7nAChR was also identified expressed in mitochondria, and it could regulate cytokines production and cellular apoptosis after being activated by intracellular acetylcholine (Ach) 90-92. Further studies indicated that activated mitochondrial α7nAChR significantly suppressed mitochondrial DNA release and activation of NACHT, LRR and PYD, domains-containing protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome, as a result, expressions of IL-1β and HMGB1 were suppressed 92. Therefore, the anti-inflammatory mechanisms of α7nAChR involve various locations and multiple levels.

α7nAChR and immune function

Monocytes and macrophages

Macrophages are believed to be the main source of inflammatory mediators during the courses of acute inflammation 93. In the initial phases of inflammation, macrophages are activated and migrate into target lesions to remove microbes and associated metabolite and apoptotic cells. This process involves the synergistic effects of endothelials and multiple signal molecules, including MCP-1, interferon (IFN)-γ, GM-colony stimulating factor (CSF), and G-CSF 94. Activated macrophages can also secrete macrophage inflammatory protein-1α (MIP-1α), MCP-1, and IL-8 to induce more macrophages recruitment and activation 94. Additionally, factors that targeting polarization of M1 or M2 can significantly alter the outcome of diseases as well 95. In critical illness, however, the structure as well as the function of macrophages becomes abnormal, as manifested by over-activation, impaired phagocytosis and apoptosis and attenuated bacterial eradication 96-98.

GTS-21 has been reported to alleviate proliferation arrest of macrophages induced by LPS 33. Ravikumar and colleagues have also noted that enhanced bacteria eradication was seen in hyperoxia implicated macrophages after treated by GTS-21, which were related to improved macrophages phagocytosis 55. Hence, α7nAChR acted as an effective target for alleviating tissue damage and improving outcome partly through regulating immune function of macrophages in critical diseases. Other important pro-survival and anti-inflammatory effects were that activated α7nAChR could abate macrophages apoptosis and induce M2 subtypes differentiation 99.

Neutrophils

Neutrophils are important effectors of innate immune response, and mobilized early in acute inflammation 100. Nonetheless, studies have uncovered multiple dysfunctions of neutrophils, mainly characterized by impaired chemotactic activity and delayed apoptosis, resulted in inadequate neutrophil migration 101, 102. Neutrophils dysfunctions contributed to increased incidence of nosocomial infections, and excess accumulation of neutrophils was noted as major damage to tissues in critical illnesses 101, 103. Thus, properly regulating the chemotaxis and apoptotic activities of neutrophils might be beneficial for lessening tissue injury.

GTS-21 effectively modulated accumulation and activation of polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs), α7nAChR-/- mice, however, showed uncontrolled PMN infiltration and excessive production of TNF-α and CXCL-1 in comparison with wild-type mice after being challenged with immune complex 104. Though a series of investigations showed that pro-inflammatory cytokines, TNF-α as an example, rendered neutrophils to accumulate in inflammatory sites, but simply lowering TNF-α production did not significantly inhibited neutrophils accumulation 105. In severe infection or trauma conditions, some major chemokines, such as CXCL-1 and IL-8, which were crucial for neutrophils migration, showed significantly enhanced production 106. Nicotine was confirmed to inhibit neutrophils infiltration through reducing CXCL-1 and IL-8 levels 107, 108. In addition, studies showed that prevention of tissue injury by stimulating α7nAChR might be partly due to a decreased generation of neutrophils ROS by blunting FcγRs or C5aRs 104. Therefore, protective mechanisms of α7nAChR on neutrophils mainly aimed at migrating affected neutrophils to kill invading pathogens and alleviating tissue injury. Nevertheless, α7nAChR activation has not been evidenced in regulating delayed apoptosis of neutrophils under severe conditions 109.

Dendritic cells

DCs are specific with antigen presenting and known to bridge the innate and adaptive immune systems by inducing the Th cells polarization 110, 111. Immature DCs show low competence for stimulating Th cells but with advantages of capturing and processing antigens. However, they express major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-I, MHC-II and other costimulatory molecules, including CD80, CD86, and CD40 when they become mature 111. Therefore, dysfunction of DCs will result in altered immune response. In critical illness, such as severe sepsis, DCs suffered from decreased number due to elevated apoptotic activities and immune dysfunctions which involved reduced expressions of surface molecules, decreased cytokines secretion and inhibited competency for stimulating T cells 112, 113.

Studies have shown that immature DCs developed with lowered endocytic and phagocytic activities after α7nAChR activation. Mature DCs, likewise, manifested reduced expressions of surface molecules and decreased production of IL-12 under nicotine exposure 114, indicating that the effects of α7nAChR on DCs focused on attenuating excessive inflammation and maintaining DCs functional homeostasis, which varied with cells situations. Further studies revealed that these effects were associated with up-regulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors-γ (PPAR-γ) 115. Additionally, secreted lymphocyte antigen-6/urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor-related peptide (SLURP)-1, which was an endogenous α7 nAChR allosteric ligand and expressed in DCs, enhanced α7nAChR action by increasing Ach levels 116. However, few studies showed the association between α7nAChR action and apoptosis of DCs.

T lymphocytes

T cells can be divided into three types, namely Th cells, cytotoxic T cells (CTL), and regulatory T cells (Treg) based on different immune functions 117. Th cells are the most important component of adaptive immune system, and they are divided into Th1, Th2, Th17 subgroups under different cytokines stimuli 118. Therefore, dysfunctions of Th cells are closely related to the outcome of severe illness.

The interaction between α7nAChR and CD4+ T cells was considered to be of great importance in immune response. CD4+ T cells were essential for the CAP, as evidenced by reestablishment of anti-inflammatory potential of α7nAChR agonists that failed to suppress TNF-α production in nude mice but succeeded with CD4+CD25- lymphocytes transfer119. Therefore, effective modulation of T cells' function might enhance the protective effects of α7nAChR 119. Ach was also synthesized and released by T cells in autocrine or paracrine fashion, indicating a possible self-regulatory mechanism of T cells in maintaining functional homeostasis 120. The same role was seen with SLURP-1 that could be provoked by T cells to activating α7nAChR 120. Accumulating evidences showed that α7nAChR activation markedly inhibited Th1 differentiation and activation but augmented Th2 response 121. Further researches identified that these effects resulted from altered expressions of surface molecules on DCs and suppressed activities of T cells' NF-κB after α7nAChR stimulation 32, 114. In α7nAChR-/- animal models, however, T cells were more prone to differentiate into Th1 lineages 18. Other action targets, which were accounted for the modulation of α7nAChR in T cells, involved Th1 cell-specific T-box transcription factor (TBX21). GTS-21 significantly reduced the expression of TBX21 that was important in facilitating Th1 proliferation 122. Takahashi and colleagues found that nicotine administration was able to down-regulate the expressions of adhesive molecules on monocytes and associated ligands of T cells, followed by suppressed cells interaction 123. Enhanced prostaglandin E2 production was also responsible for the suppression of mixed lymphocyte reaction upon nicotine administration while vanished effects were shown by reducing protein kinase A (PKA) and cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 activities 123. Th17 cells functioned as pro-inflammatory immune cells by releasing cytokines including IL-17A, IL-17F, and IL-22 124. Th17 cells also accounted for host immune response to invading pathogens and inflammation, but excessive production of cytokines, the IL-17 as an example, could definitely harm the host 125. Nicotine was reported to decrease Th17 cytokines' levels and suppress Th17 activation in a dose-independent pattern 121.

Tregs are characterized by immunosuppressive properties and play important roles in immune homeostasis 126-128. Expressions of α7nAChR were shown on CD4+CD25+ Tregs 129, and α7nAChR activation augmented the suppressive effects of CD4+CD25+ Tregs by up-regulating expressions of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen (CTLA)-4 and forkhead/winged helix transcription factor p3 (Foxp3), and decreasing IL-2 levels 129, indicating that α7nAChR cascades might evoke multiple anti-inflammatory mechanisms of T cells to maintain immune homeostasis.

Conclusions

The α7nAChR has been identified to be beneficial for serious conditions, as mainly manifested by attenuation of excessive inflammation and improvement in survival rates of animal models. These effects were closely related to its distinct structure characterized by high permeability for calcium and affinity to acetylcholine, which enabled α7nAChR respond quickly in the process of inflammation. α7nAChR activation exhibited extensive anti-inflammatory reactions, including lowered pro-inflammatory cytokines levels, decreased expressions of chemokines as well as adhesion molecules, and altered differentiation and activation of immune cells. All these effects were believed to be beneficial for attenuating excessive inflammation, but might be considered to harm the immune response to microbial infection in the early stages. However, little researches showed detrimental effects of α7nAChR agonists with pre-treatment or early administration, which might be due to self-regulation of α7nAChR as an ion channel under physiological conditions, which maintained hemostasis by self-regulation 130. Additionally, the α7nAChR was reported to become desensitization in the early stages of critical conditions, which might also account for uncontrolled inflammation, and reversing its desensitization would be of great importance to attenuate excessive inflammation 31. Furthermore, multiple signaling pathways were responsible for the anti-inflammatory mechanisms of α7nAChR cascades, represented by JAK2-STAT3-NF-κB axis that interacted with other pathways to enhance its protective effects synergistically. With more and more protective evidences of α7nAChR have been shown in animal models with severe conditions. A few studies have already focused on exploring effective drugs concerning α7nAChR activation in clinical settings, which were based on some successful results by improving cognition in neurodegenerative diseases 131. Taking GTS-21 for an example, it significantly inhibited LPS induced cytokines expression in human trials and modulated innate immune responses 79. Additionally, new agonists of α7nAChR have also been evaluated in clinical trials, which might be promising in improving neurological dysfunction 132. Thus, it was of great importance to have a good understanding of protective mechanisms of α7nAChR relevant to clinical settings.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported, in part, by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation (Nos. 81130035, 81372054, 81121004), and the National Basic Research Program of China (No. 2012CB518102).

Abbreviations

- α7nAchR

alpha 7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor

- CAP

cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway;ALI: acute lung injury

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor-α;IL-1β: interleukin-1β

- HMGB1

high mobility group box-1 protein

- DCs

dendritic cells

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- NF-Κb

nuclear factor-κB

- TBI

traumatic brain injury

- HO-1

heme oxygenase

- IRI

Ischemia-reperfusion injury

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- MCP-1

monocyte chemotactic protein-1

- ICAM-1

intracellular adhesion molecule 1

- JAK2

Janus kinase 2

- STAT3

signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

- PAMPs

pathogen associated molecular patterns

- IKK

IκB kinases

- MyD88

Myeloid differentiation factor 88

- TLR

Toll-like receptor

- IRAK-M

Interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase M;TRAF6: TNF receptor-associated factor 6

- IFN-γ

interferon (IFN)-γ

- GM-CSF

GM-colony stimulating factor

- MIP-1α

macrophage inflammatory protein-1α

- PMNs

polymorphonuclear neutrophils

- MHC

major histocompatibility complex

- PPAR-γ

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors-γ

- SLURP-1

secreted lymphocyte antigen-6/urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor-related peptide -1

- CTL

cytotoxic T cells

- Treg

regulatory T cells

- TBX21

Th1 cell-specific T-box transcription factor

- PKA

protein kinase A

- COX-2

cyclooxygenase-2

- TGF-β

transforming growth factor

- CTLA-4

cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen-4

- Foxp3

forkhead/winged helix transcription factor p3.

References

- 1.Rosas-Ballina M, Tracey KJ. Cholinergic control of inflammation. J Intern Med. 2009;265:663–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2009.02098.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pavlov VA, Tracey KJ. Controlling inflammation: the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway. Biochem Soc Trans. 2006;34:1037–40. doi: 10.1042/BST0341037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reys LG, Ortiz-Pomales YT, Lopez N, Cheadle G, De Oliveira PG, Eliceiri B. et al. Uncovering the neuroenteric-pulmonary axis: vagal nerve stimulation prevents acute lung injury following hemorrhagic shock. Life Sci. 2013;92:783–92. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2013.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mioni C, Bazzani C, Giuliani D, Altavilla D, Leone S, Ferrari A. et al. Activation of an efferent cholinergic pathway produces strong protection against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:2621–8. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000186762.05301.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Minutoli L, Squadrito F, Nicotina PA, Giuliani D, Ottani A, Polito F. et al. Melanocortin 4 receptor stimulation decreases pancreatitis severity in rats by activation of the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:1089–96. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318207ea80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fodale V, Santamaria LB. Cholinesterase inhibitors improve survival in experimental sepsis: a new way to activate the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:622–3. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0B013E31816297CE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Su X, Lee JW, Matthay ZA, Mednick G, Uchida T, Fang X. et al. Activation of the alpha7 nAChR reduces acid-induced acute lung injury in mice and rats. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2007;37:186–92. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0240OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borovikova LV, Ivanova S, Zhang M, Yang H, Botchkina GI, Watkins LR. et al. Vagus nerve stimulation attenuates the systemic inflammatory response to endotoxin. Nature. 2000;405:458–62. doi: 10.1038/35013070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tracey KJ. Physiology and immunology of the cholinergic antiinflammatory pathway. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:289–96. doi: 10.1172/JCI30555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haydar SN, Dunlop J. Neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors-targets for the development of drugs to treat cognitive impairment associated with schizophrenia and Alzheimer's disease. Curr Top Med Chem. 2010;10:144–52. doi: 10.2174/156802610790410983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kong FJ, Ma LL, Zhang HH, Zhou JQ. Alpha 7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonist GTS-21 mitigates isoflurane-induced cognitive impairment in aged rats. J Surg Res. 2015;194:255–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2014.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beinat C, Banister SD, Herrera M, Law V, Kassiou M. The therapeutic potential of alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (alpha7 nAChR) agonists for the treatment of the cognitive deficits associated with schizophrenia. CNS Drugs. 2015;29:529–42. doi: 10.1007/s40263-015-0260-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Albuquerque E X, Pereira EF, Alkondon M, Rogers SW. Mammalian nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: from structure to function. Physiol Rev. 2009;89:73–120. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00015.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bencherif M, Lippiello PM, Lucas R, Marrero MB. Alpha7 nicotinic receptors as novel therapeutic targets for inflammation-based diseases. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011;68:931–49. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0525-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li J, Mathieu S L, Harris R, Ji J, Anderson DJ, Malysz J. et al. Role of alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in regulating tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) as revealed by subtype selective agonists. J Neuroimmunol. 2011;239:37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huston JM, Gallowitsch-Puerta M, Ochani M, Ochani K, Yuan R, Rosas-Ballina M. et al. Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation reduces serum high mobility group box 1 levels and improves survival in murine sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:2762–8. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000288102.15975.BA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pavlov VA, Ochani M, Yang LH, Gallowitsch-Puerta M, Ochani K, Lin X. et al. Selective alpha7-nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonist GTS-21 improves survival in murine endotoxemia and severe sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:1139–44. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000259381.56526.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Maanen MA, Stoof SP, Larosa GJ, Vervoordeldonk MJ, Tak PP. Role of the cholinergic nervous system in rheumatoid arthritis: aggravation of arthritis in nicotinic acetylcholine receptor alpha7 subunit gene knockout mice. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:1717–23. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.118554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang H, Liao H, Ochani M, Justiniani M, Lin X, Yang L. et al. Cholinergic agonists inhibit HMGB1 release and improve survival in experimental sepsis. Nat Med. 2004;10:1216–21. doi: 10.1038/nm1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Westerloo DJ, Giebelen IA, Florquin S, Bruno MJ, Larosa GJ, Ulloa L. et al. The vagus nerve and nicotinic receptors modulate experimental pancreatitis severity in mice. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1822–30. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dani JA, Bertrand D. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and nicotinic cholinergic mechanisms of the central nervous system. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2007;47:699–729. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.47.120505.105214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Conejero-Goldberg C, Davies P, Ulloa L. Alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor: a link between inflammation and neurodegeneration. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2008;32:693–706. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glennon RA. Medicinal chemistry of alpha4beta2 nicotinic cholinergic receptor ligands. Prog Med Chem. 2004;42:55–123. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6468(04)42002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thompson AJ, Lester HA, Lummis SC. The structural basis of function in Cys-loop receptors. Q Rev Biophys. 2010;43:449–99. doi: 10.1017/S0033583510000168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Drisdel RC, Green WN. Neuronal alpha-bungarotoxin receptors are alpha7 subunit homomers. J Neurosci. 2000;20:133–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-01-00133.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mohamed TS, Jayakar SS, Hamouda AK. Orthosteric and Allosteric Ligands of Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors for Smoking Cessation. Front Mol Neurosci. 2015;8:71. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2015.00071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thomsen MS, Mikkelsen JD. The alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor complex: one, two or multiple drug targets? Curr Drug Targets. 2012;13:707–20. doi: 10.2174/138945012800399035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Uteshev VV. alpha7 nicotinic ACh receptors as a ligand-gated source of Ca(2+) ions: the search for a Ca(2+) optimum. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2012;740:603–38. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-2888-2_27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mazurov A, Hauser T, Miller CH. Selective alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor ligands. Curr Med Chem. 2006;13:1567–84. doi: 10.2174/092986706777442011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Papke RL, Kem WR, Soti F, Lopez-Hernandez GY, Horenstein NA. Activation and desensitization of nicotinic alpha7-type acetylcholine receptors by benzylidene anabaseines and nicotine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;329:791–807. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.150151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang J, Xue F, Whiteaker P, Li C, Wu W, Shen B. et al. Desensitization of alpha7 nicotinic receptor is governed by coupling strength relative to gate tightness. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:25331–40. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.221754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang H, Yu M, Ochani M, Amella CA, Tanovic M, Susarla S. et al. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor alpha7 subunit is an essential regulator of inflammation. Nature. 2003;421:384–8. doi: 10.1038/nature01339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khan MA, Farkhondeh M, Crombie J, Jacobson L, Kaneki M, Martyn JA. Lipopolysaccharide upregulates alpha7 acetylcholine receptors: stimulation with GTS-21 mitigates growth arrest of macrophages and improves survival in burned mice. Shock. 2012;38:213–9. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e31825d628c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yeboah MM, Xue X, Javdan M, Susin M, Metz CN. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor expression and regulation in the rat kidney after ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008;295:F654–61. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90255.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Terrando N, Yang T, Ryu JK, Newton PT, Monaco C, Feldmann M. et al. Stimulation of the alpha 7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor protects against neuroinflammation after tibia fracture and endotoxemia in mice. Mol Med. 2014;20:667–75. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2014.00143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Costantini TW, Krzyzaniak M, Cheadle GA, Putnam JG, Hageny AM, Lopez N. et al. Targeting alpha-7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor in the enteric nervous system: a cholinergic agonist prevents gut barrier failure after severe burn injury. Am J Pathol. 2012;181:478–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tarras SL, Diebel LN, Liberati DM, Ginnebaugh K. Pharmacologic stimulation of the nicotinic anti-inflammatory pathway modulates gut and lung injury after hypoxia-reoxygenation injury. Surgery. 2013;154:841–7. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2013.07.018. discussion 847-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sun L, Zhang GF, Zhang X, Liu Q, Liu JG, Su DF. et al. Combined administration of anisodamine and neostigmine produces anti-shock effects: involvement of alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2012;33:761–6. doi: 10.1038/aps.2012.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lawrence T. The nuclear factor NF-kappaB pathway in inflammation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2009;1:a001651. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yoshikawa H, Kurokawa M, Ozaki N, Nara K, Atou K, Takada E. et al. Nicotine inhibits the production of proinflammatory mediators in human monocytes by suppression of I-kappaB phosphorylation and nuclear factor-kappaB transcriptional activity through nicotinic acetylcholine receptor alpha7. Clin Exp Immunol. 2006;146:116–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03169.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.De Jonge WJ, Van Der Zanden EP, The FO, Bijlsma MF, Van Westerloo DJ, Bennink RJ. et al. Stimulation of the vagus nerve attenuates macrophage activation by activating the Jak2-STAT3 signaling pathway. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:844–51. doi: 10.1038/ni1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Valparaiso AP, Vicente DA, Bograd BA, Elster EA, Davis TA. Modeling acute traumatic injury. J Surg Res. 2015;194:220–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2014.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jeschke MG, Chinkes DL, Finnerty CC, Kulp G, Suman OE, Norbury WB. et al. Pathophysiologic response to severe burn injury. Ann Surg. 2008;248:387–401. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181856241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Costantini TW, Loomis WH, Putnam JG, Drusinsky D, Deree J, Choi S. et al. Burn-induced gut barrier injury is attenuated by phosphodiesterase inhibition: effects on tight junction structural proteins. Shock. 2009;31:416–22. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181863080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hoffmeister PG, Donat CK, Schuhmann MU, Voigt C, Walter B, Nieber K. et al. Traumatic brain injury elicits similar alterations in alpha7 nicotinic receptor density in two different experimental models. Neuromolecular Med. 2011;13:44–53. doi: 10.1007/s12017-010-8136-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fan YY, Zhang ST, Yu LS, Ye GH, Lin KZ, Wu SZ. et al. The time-dependent expression of alpha7nAChR during skeletal muscle wound healing in rats. Int J Legal Med. 2014;128:779–86. doi: 10.1007/s00414-014-1001-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Osta WA, El-Osta MA, Pezhman EA, Raad RA, Ferguson K, Mckelvey GM. et al. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor gene expression is altered in burn patients. Anesth Analg. 2010;110:1355–9. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181d41512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Verbois SL, Hopkins DM, Scheff SW, Pauly JR. Chronic intermittent nicotine administration attenuates traumatic brain injury-induced cognitive dysfunction. Neuroscience. 2003;119:1199–208. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00206-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stearns-Kurosawa DJ, Osuchowski MF, Valentine C, Kurosawa S, Remick DG. The pathogenesis of sepsis. Annu Rev Pathol. 2011;6:19–48. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vincent JL, Opal SM, Marshall JC, Tracey KJ. Sepsis definitions: time for change. Lancet. 2013;381:774–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61815-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Russell JA. Management of sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1699–713. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra043632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cedillo JL, Arnalich F, Martin-Sanchez C, Quesada A, Rios JJ, Maldifassi MC. et al. Usefulness of alpha7 nicotinic receptor messenger RNA levels in peripheral blood mononuclear cells as a marker for cholinergic antiinflammatory pathway activity in septic patients: results of a pilot study. J Infect Dis. 2015;211:146–55. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tsoyi K, Jang HJ, Kim JW, Chang HK, Lee YS, Pae HO. et al. Stimulation of alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor by nicotine attenuates inflammatory response in macrophages and improves survival in experimental model of sepsis through heme oxygenase-1 induction. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;14:2057–70. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Su X, Matthay MA, Malik AB. Requisite role of the cholinergic alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor pathway in suppressing Gram-negative sepsis-induced acute lung inflammatory injury. J Immunol. 2010;184:401–10. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sitapara RA, Antoine DJ, Sharma L, Patel VS, Ashby CR Jr, Gorasiya S. et al. The alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonist GTS-21 improves bacterial clearance in mice by restoring hyperoxia-compromised macrophage function. Mol Med. 2014;20:238–47. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2013.00086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 56.Johnson ER, Matthay MA. Acute lung injury: epidemiology, pathogenesis, and treatment. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2010;23:243–52. doi: 10.1089/jamp.2009.0775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zambon M, Vincent JL. Mortality rates for patients with acute lung injury/ARDS have decreased over time. Chest. 2008;133:1120–7. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-2134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bhatia M, Zemans RL, Jeyaseelan S. Role of chemokines in the pathogenesis of acute lung injury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2012;46:566–72. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2011-0392TR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Reiss LK, Uhlig U, Uhlig S. Models and mechanisms of acute lung injury caused by direct insults. Eur J Cell Biol. 2012;91:590–601. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2011.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Herold S, Gabrielli NM, Vadasz I. Novel concepts of acute lung injury and alveolar-capillary barrier dysfunction. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2013;305:L665–81. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00232.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ni YF, Tian F, Lu ZF, Yang GD, Fu HY, Wang J. et al. Protective effect of nicotine on lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in mice. Respiration. 2011;81:39–46. doi: 10.1159/000319151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kox M, Pompe JC, Peters E, Vaneker M, Van Der Laak JW, Van Der Hoeven JG. et al. alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonist GTS-21 attenuates ventilator-induced tumour necrosis factor-alpha production and lung injury. Br J Anaesth. 2011;107:559–66. doi: 10.1093/bja/aer202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dos Santos CC, Shan Y, Akram A, Slutsky AS, Haitsma JJ. Neuroimmune regulation of ventilator-induced lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:471–82. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201002-0314OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Roman J, Koval M. Control of lung epithelial growth by a nicotinic acetylcholine receptor: the other side of the coin. Am J Pathol. 2009;175:1799–801. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.090689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sanderson TH, Reynolds CA, Kumar R, Przyklenk K, Huttemann M.Molecular mechanisms of ischemia-reperfusion injury in brain. pivotal role of the mitochondrial membrane potential in reactive oxygen species generation. Mol Neurobiol. 2013;47:9–23. doi: 10.1007/s12035-012-8344-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bliksoen M, Baysa A, Eide L, Bjoras M, Suganthan R, Vaage J. et al. Mitochondrial DNA damage and repair during ischemia-reperfusion injury of the heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2015;78:9–22. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2014.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Datta G, Fuller BJ, Davidson BR. Molecular mechanisms of liver ischemia reperfusion injury: insights from transgenic knockout models. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:1683–98. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i11.1683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Taha MO, Miranda-Ferreira R, Chang AC, Rodrigues AM, Fonseca IS, Toral LB. et al. Effect of ischemic preconditioning on injuries caused by ischemia and reperfusion in rat intestine. Transplant Proc. 2012;44:2304–8. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2012.07.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Eltzschig HK, Eckle T. Ischemia and reperfusion-from mechanism to translation. Nat Med. 2011;17:1391–401. doi: 10.1038/nm.2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Grebenchikov OA, Likhvantsev VV, Plotnikov E, Silachev DN, Pevzner IB, Zorova LD. et al. [Molecular mechanisms of ischemic-reperfusion syndrome and its personalized therapy] Anesteziol Reanimatol. 2014;2014:59–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yeboah MM, Xue X, Duan B, Ochani M, Tracey KJ, Susin M. et al. Cholinergic agonists attenuate renal ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats. Kidney Int. 2008;74:62–9. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang Q, Wang F, Li X, Yang Q, Li X, Xu N. et al. Electroacupuncture pretreatment attenuates cerebral ischemic injury through alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor-mediated inhibition of high-mobility group box 1 release in rats. J Neuroinflammation. 2012;9:24. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-9-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Xiong J, Yuan YJ, Xue FS, Wang Q, Cheng Y, Li RP. et al. Postconditioning with alpha7nAChR agonist attenuates systemic inflammatory response to myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats. Inflammation. 2012;35:1357–64. doi: 10.1007/s10753-012-9449-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Forsmark CE, Baillie J. AGA Institute technical review on acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2022–44. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sah RP, Garg P, Saluja AK. Pathogenic mechanisms of acute pancreatitis. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2012;28:507–15. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e3283567f52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sah RP, Dawra RK, Saluja AK. New insights into the pathogenesis of pancreatitis. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2013;29:523–30. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e328363e399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zheng L, Xue J, Jaffee EM, Habtezion A. Role of immune cells and immune-based therapies in pancreatitis and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1230–40. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.12.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ji B, Gaiser S, Chen X, Ernst SA, Logsdon CD. Intracellular trypsin induces pancreatic acinar cell death but not NF-kappaB activation. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:17488–98. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.005520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kox M, Pompe JC, Gordinou De Gouberville MC, Van Der Hoeven JG, Hoedemaekers CW, Pickkers P. Effects of the alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonist GTS-21 on the innate immune response in humans. Shock. 2011;36:5–11. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3182168d56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kox M, Van Velzen JF, Pompe JC, Hoedemaekers CW, Van Der Hoeven JG, Pickkers P. GTS-21 inhibits pro-inflammatory cytokine release independent of the Toll-like receptor stimulated via a transcriptional mechanism involving JAK2 activation. Biochem Pharmacol. 2009;78:863–72. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.06.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Baez-Pagan CA, Delgado-Velez M, Lasalde-Dominicci JA. Activation of the Macrophage alpha7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor and Control of Inflammation. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2015;10:468–76. doi: 10.1007/s11481-015-9601-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Solt LA, May MJ. The IkappaB kinase complex: master regulator of NF-kappaB signaling. Immunol Res. 2008;42:3–18. doi: 10.1007/s12026-008-8025-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.O'neill LA. The role of MyD88-like adapters in Toll-like receptor signal transduction. Biochem Soc Trans. 2003;31:643–7. doi: 10.1042/bst0310643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Li Q, Zhou XD, Kolosov VP, Perelman JM. Nicotine reduces TNF-alpha expression through a alpha7 nAChR/MyD88/NF-kB pathway in HBE16 airway epithelial cells. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2011;27:605–12. doi: 10.1159/000329982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Janssens S, Beyaert R. Functional diversity and regulation of different interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase (IRAK) family members. Mol Cell. 2003;11:293–302. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kobayashi K, Hernandez LD, Galan JE, Janeway CA Jr, Medzhitov R, Flavell RA. IRAK-M is a negative regulator of Toll-like receptor signaling. Cell. 2002;110:191–202. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00827-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Maldifassi MC, Atienza G, Arnalich F, Lopez-Collazo E, Cedillo JL, Martin-Sanchez C. et al. A new IRAK-M-mediated mechanism implicated in the anti-inflammatory effect of nicotine via alpha7 nicotinic receptors in human macrophages. PLoS One. 2014;9:e108397. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tyagi E, Agrawal R, Nath C, Shukla R. Cholinergic protection via alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and PI3K-Akt pathway in LPS-induced neuroinflammation. Neurochem Int. 2010;56:135–42. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2009.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kim TH, Kim SJ, Lee SM. Stimulation of the alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor protects against sepsis by inhibiting Toll-like receptor via phosphoinositide 3-kinase activation. J Infect Dis. 2014;209:1668–77. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Gergalova G, Lykhmus O, Kalashnyk O, Koval L, Chernyshov V, Kryukova E. et al. Mitochondria express alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors to regulate Ca2+ accumulation and cytochrome c release: study on isolated mitochondria. PLoS One. 2012;7:e31361. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lykhmus O, Gergalova G, Koval L, Zhmak M, Komisarenko S, Skok M. Mitochondria express several nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subtypes to control various pathways of apoptosis induction. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2014;53:246–52. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2014.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lu B, Kwan K, Levine YA, Olofsson PS, Yang H, Li J. et al. alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor signaling inhibits inflammasome activation by preventing mitochondrial DNA release. Mol Med. 2014;20:350–8. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2013.00117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Arango Duque G, Descoteaux A. Macrophage cytokines: involvement in immunity and infectious diseases. Front Immunol. 2014;5:491. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Friedl P, Weigelin B. Interstitial leukocyte migration and immune function. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:960–9. doi: 10.1038/ni.f.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Mosser DM, Edwards JP. Exploring the full spectrum of macrophage activation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:958–69. doi: 10.1038/nri2448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Larroche C, Mouthon L. Pathogenesis of hemophagocytic syndrome (HPS) Autoimmun Rev. 2004;3:69–75. doi: 10.1016/S1568-9972(03)00091-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Morrow DM, Entezari-Zaher T, Romashko J, Azghani AO, Javdan M, Ulloa L. et al. Antioxidants preserve macrophage phagocytosis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa during hyperoxia. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;42:1338–49. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.01.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Peck-Palmer OM, Unsinger J, Chang KC, Mcdonough JS, Perlman H, Mcdunn JE. et al. Modulation of the Bcl-2 family blocks sepsis-induced depletion of dendritic cells and macrophages. Shock. 2009;31:359–66. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e31818ba2a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lee RH, Vazquez G. Evidence for a prosurvival role of alpha-7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor in alternatively (M2)-activated macrophages. Physiol Rep. 2013;1:e00189. doi: 10.1002/phy2.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kolaczkowska E, Kubes P. Neutrophil recruitment and function in health and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:159–75. doi: 10.1038/nri3399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Reutershan J, Basit A, Galkina EV, Ley K. Sequential recruitment of neutrophils into lung and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid in LPS-induced acute lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;289:L807–15. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00477.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Alves-Filho JC, Spiller F, Cunha FQ. Neutrophil paralysis in sepsis. Shock. 2010;34(Suppl 1):S15–S21. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181e7e61b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Stephan F, Yang K, Tankovic J, Soussy CJ, Dhonneur G, Duvaldestin P. et al. Impairment of polymorphonuclear neutrophil functions precedes nosocomial infections in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:315–22. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200202000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Vukelic M, Qing X, Redecha P, Koo G, Salmon JE. Cholinergic receptors modulate immune complex-induced inflammation in vitro and in vivo. J Immunol. 2013;191:1800–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1203467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Giebelen IA, Van Westerloo DJ, Larosa GJ, De Vos AF, Van Der Poll T. Stimulation of alpha 7 cholinergic receptors inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced neutrophil recruitment by a tumor necrosis factor alpha-independent mechanism. Shock. 2007;27:443–7. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000245016.78493.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.De Filippo K, Dudeck A, Hasenberg M, Nye E, Van Rooijen N, Hartmann K. et al. Mast cell and macrophage chemokines CXCL1/CXCL2 control the early stage of neutrophil recruitment during tissue inflammation. Blood. 2013;121:4930–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-02-486217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Sadis C, Teske G, Stokman G, Kubjak C, Claessen N, Moore F. et al. Nicotine protects kidney from renal ischemia/reperfusion injury through the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway. PLoS One. 2007;2:e469. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Greene CM, Ramsay H, Wells RJ, O'neill SJ, Mcelvaney NG. Inhibition of Toll-like receptor 2-mediated interleukin-8 production in Cystic Fibrosis airway epithelial cells via the alpha7-nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Mediators Inflamm. 2010;2010:423241. doi: 10.1155/2010/423241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Xu M, Scott JE, Liu KZ, Bishop HR, Renaud DE, Palmer RM. et al. The influence of nicotine on granulocytic differentiation-inhibition of the oxidative burst and bacterial killing and increased matrix metalloproteinase-9 release. BMC Cell Biol. 2008;9:19. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-9-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Reis E Sousa C. Dendritic cells in a mature age. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:476–83. doi: 10.1038/nri1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.De Jong EC, Smits HH, Kapsenberg ML. Dendritic cell-mediated T cell polarization. Springer Semin Immunopathol. 2005;26:289–307. doi: 10.1007/s00281-004-0167-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Pene F, Courtine E, Ouaaz F, Zuber B, Sauneuf B, Sirgo G. et al. Toll-like receptors 2 and 4 contribute to sepsis-induced depletion of spleen dendritic cells. Infect Immun. 2009;77:5651–8. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00238-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Poehlmann H, Schefold JC, Zuckermann-Becker H, Volk HD, Meisel C. Phenotype changes and impaired function of dendritic cell subsets in patients with sepsis: a prospective observational analysis. Crit Care. 2009;13:R119. doi: 10.1186/cc7969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Yanagita M, Mori K, Kobayashi R, Kojima Y, Kubota M, Miki K. et al. Immunomodulation of dendritic cells differentiated in the presence of nicotine with lipopolysaccharide from Porphyromonas gingivalis. Eur J Oral Sci. 2012;120:408–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2012.00992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Yanagita M, Kobayashi R, Kojima Y, Mori K, Murakami S. Nicotine modulates the immunological function of dendritic cells through peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma upregulation. Cell Immunol. 2012;274:26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Fujii T, Horiguchi K, Sunaga H, Moriwaki Y, Misawa H, Kasahara T. et al. SLURP-1, an endogenous alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor allosteric ligand, is expressed in CD205(+) dendritic cells in human tonsils and potentiates lymphocytic cholinergic activity. J Neuroimmunol. 2014;267:43–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2013.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Geginat J, Paroni M, Maglie S, Alfen JS, Kastirr I, Gruarin P. et al. Plasticity of human CD4 T cell subsets. Front Immunol. 2014;5:630. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Zhu J, Yamane H, Paul WE. Differentiation of effector CD4 T cell populations (*) Annu Rev Immunol. 2010;28:445–89. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Pena G, Cai B, Ramos L, Vida G, Deitch EA, Ulloa L. Cholinergic regulatory lymphocytes re-establish neuromodulation of innate immune responses in sepsis. J Immunol. 2011;187:718–25. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Kawashima K, Fujii T, Moriwaki Y, Misawa H, Horiguchi K. Non-neuronal cholinergic system in regulation of immune function with a focus on alpha7 nAChRs. Int Immunopharmacol. 2015;29:127–34. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2015.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Nizri E, Irony-Tur-Sinai M, Lory O, Orr-Urtreger A, Lavi E, Brenner T. Activation of the cholinergic anti-inflammatory system by nicotine attenuates neuroinflammation via suppression of Th1 and Th17 responses. J Immunol. 2009;183:6681–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Wu S, Zhao H, Luo H, Xiao X, Zhang H, Li T. et al. GTS-21, an alpha7-nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonist, modulates Th1 differentiation in CD4 T cells from patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Exp Ther Med. 2014;8:557–562. doi: 10.3892/etm.2014.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Takahashi HK, Iwagaki H, Hamano R, Kanke T, Liu K, Sadamori H. et al. The immunosuppressive effects of nicotine during human mixed lymphocyte reaction. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;559:69–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Harrington LE, Hatton RD, Mangan PR, Turner H, Murphy TL, Murphy KM. et al. Interleukin 17-producing CD4+ effector T cells develop via a lineage distinct from the T helper type 1 and 2 lineages. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1123–32. doi: 10.1038/ni1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Nakae S, Nambu A, Sudo K, Iwakura Y. Suppression of immune induction of collagen-induced arthritis in IL-17-deficient mice. J Immunol. 2003;171:6173–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.11.6173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Qiao M, Thornton AM, Shevach EM. CD4+ CD25+ [corrected] regulatory T cells render naive CD4+ CD25- T cells anergic and suppressive. Immunology. 2007;120:447–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02544.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Bach JF. Regulatory T cells under scrutiny. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:189–98. doi: 10.1038/nri1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Hanschen M, Tajima G, O'leary F, Hoang K, Ikeda K, Lederer JA. Phospho-flow cytometry based analysis of differences in T cell receptor signaling between regulatory T cells and CD4+ T cells. J Immunol Methods. 2012;376:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2011.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Wang DW, Zhou RB, Yao YM, Zhu XM, Yin YM, Zhao GJ. et al. Stimulation of alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor by nicotine increases suppressive capacity of naturally occurring CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in mice in vitro. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;335:553–61. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.169961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Marrero MB, Bencherif M, Lippiello PM, Lucas R. Application of alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonists in inflammatory diseases: an overview. Pharm Res. 2011;28:413–6. doi: 10.1007/s11095-010-0283-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Lieberman JA, Dunbar G, Segreti AC, Girgis RR, Seoane F, Beaver JS. et al. A randomized exploratory trial of an alpha-7 nicotinic receptor agonist (TC-5619) for cognitive enhancement in schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38:968–75. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Barbier AJ, Hilhorst M, Van Vliet A, Snyder P, Palfreyman MG, Gawryl M. et al. Pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics, safety, and tolerability of encenicline, a selective alpha7 nicotinic receptor partial agonist, in single ascending-dose and bioavailability studies. Clin Ther. 2015;37:311–24. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2014.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]