Abstract

MicroRNAs are a novel class of gene regulators that function as oncogenes or tumor suppressors. In our current study, we investigated the role of miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p in the regulation of Twist1 expression and EMT process. Our bioinformatics analysis suggested that on the 3' UTR of Twist1, there are two conserved miRNA recognition sites for miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p respectively. Interestingly, overexpression of miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p significantly suppressed the activity of luciferase reporter containing Twist1-3' UTR, reduced mRNA and protein level of EMT related genes such as TWIST1, N-cadherin, α-SMA and Fibronectin, and repressed MMP9 and MMP2 activity, as well as cell migration and invasion. Conversely, inhibition of miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p significantly increased TWIST1, N-cadherin, α-SMA and Fibronectin protein expression. In addition, Twist1 co-transfection significantly ameliorated the loss of cell migration and invasion. Moreover, overexpression of miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p dramatically suppressed the ability of BGC823 cells to form colonies in vitro and develop tumors in vivo in nude mice. Finally, qPCR and Western blot analysis showed that miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p were significantly reduced in clinical gastric cancer tissue, whereas Twist1 mRNA and protein were significantly up-regulated, suggesting that this aberrant down-regulation of miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p might be associated with the abnormal regulation of Twist1 and the EMT process in gastric cancer development. Our results help to elucidate a novel and important mechanism for the regulation of Twist1 in the development of cancer.

Keywords: miR-15a-3p, miR-16-1-3p, Twist1, Gastric cancer, cell invasion and metastasis.

Introduction

As one of the most common malignant tumors, gastric cancer (GC) is the fourth most common cancer and the second leading cause of cancer mortality worldwide 1-3. Despite advances in diagnosis and treatment, the 5-year survival rate of GC is only 20 percent 4. Because of the high mortality of GC, early diagnosis and treatment has become an urgent issue. Previous studies indicated that the occurrence and development of GC is a complicated process that involves a variety of cross-linked factors such as environmental infection 5, cell proliferation and cell cycle dysfunction 6, angiogenesis 7, 8, cell invasion and metastasis9. Molecular mechanism studies showed that GC involves aberrant expression of oncogenes, tumor suppressor genes, apoptosis-related genes and metastasis-related genes 4. Recent studies have shown that cancer cell metastasis is the primary cause of mortality in human GC patients 10, 11. Invasion and metastasis are exceedingly complex processes that enable cancer cells to escape from the primary tumor mass and colonize new sites 11.

Growing evidence demonstrated that the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) represent as a developmental process plays important roles in invasion and metastasis in GC, colorectal cancer, breast cancer and liver cancer 12-14. During cancer progression, tumor cells undergoing an EMT process acquire mesenchymal cell characteristics, losing epithelial markers and gaining cell motility to promote cancer cell migration across the basal membrane and invasion of the surrounding microenvironment 14. Moreover, the EMT process increases tumor cell resistance to apoptosis and chemotherapeutic drugs 15. The EMT process can be regulated by a diverse array of tumor-related genes, such as Snail1/2, Slug, Zeb1/2, Twist1 and some other transcription factors 16-19. Studies showed that the transcription factor Twist1 is important for regulating EMT process, and over-expression of Twist1 significantly induced cell morphological changes as well as increased cell migration and invasion ability by regulating the expression of E-cadherin, N-cadherin, c-fos and metalloproteinase-9 20, 21. Therefore, Twist1 was suggested to have oncogenic properties. For example, microarray analysis showed that Twist1 regulates the expression of several EMT-related genes to regulate the differentiation, adhesion, and proliferation of GC cells 22. In addition, Twist1 is up-regulated in GC-associated fibroblasts and contribute to the progression of GC cells and poor patient survival 23. Moreover, Qian et al. found that Twist1 was over-expressed in NCI-N87 or AGS GC cells and promotes GC cell proliferation through the up-regulation of FoxM1 24. However, the effect and mechanism of Twist1 gene activity on cell invasion and metastasis of gastric carcinoma remain enigmatic.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are important regulators and function as oncogenes or tumor suppressors by targeting the 3' untranslated region (UTR) of messenger RNA (mRNA) to induce mRNA degradation and suppression of translation 25, 26. Growing evidence suggests that miRNAs play important roles in diverse biological processes and the dysfunction of miRNAs is involved in the development of many types of cancer, including GC 27. Recent studies showed that a series of miRNAs serve as key regulators that affect the invasion and metastasis by regulating Twist1 in a variety of tumors 28-30. In this study, we use GC cells and investigated the role of miR-15a-3p- and miR-16-1-3p-mediated gene silencing on the regulation of Twist1 expression. We found that Twist1 is a direct target of miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p, and the Twist1-EMT pathway was suppressed by miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p. Moreover, miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p negatively regulate Twist1 through interacting with the miRNA recognition elements (MREs) on the Twist1-3' untranslated region (Twist1-3' UTR). Further investigation revealed that by targeting Twist1, miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p suppressed the ability of cancer cells to form colonies in vitro and to develop tumors in vivo. Furthermore, the lower expression of miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p is correlated with substantial induction of Twist1 expression in human GC tissues, which might contribute significantly to the pathogenesis or progression of tumor formation. Taken together, our data suggest an important regulatory role of miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p in the EMT process in tumors. Thus, miR-15a-3p, miR-16-1-3p and Twist1 might be important diagnostic or therapeutic targets for EMT process in cancer and other human diseases.

Materials and Methods

Plasmid construction

HA tagged human Twist1-overexpressing plasmid pHA-Twist1 was a generous gift of Prof. Jianming Chen from Third Institute of Oceanography, State Oceanic Administration. For the construction of human Twist1-3'UTR, wildtype Twist1-3'UTR miR-15a-3p MRE, mutant Twist1-3'UTR miR-15a-3p MRE, wildtype Twist1-3'UTR miR-16-1-3p MRE and mutant Twist1-3'UTR miR-16-1-3p MRE luciferase reporters, the primer pairs shown in Supplemental Table S2 (based on the genomic sequences from the miRBase (http://www.mirbase.org, Release 19)) were designed to amplify five cDNA fragments for the full length of Twist1-3'UTR (585 bp, NM_000474.3), a truncated Twist1-3'UTR harboring a DNA fragment with the wild-type or mutated miR-15a-3p-MRE on Twist1-3'UTR (453 bp) and a truncated Twist1-3'UTR harboring a DNA fragment with the wild-type or mutated miR-16-1-3p-MRE on Twist1-3'UTR (438 bp), respectively. The resultant PCR fragments carrying a SacI site and a HindIII site were subcloned into the pGL3-control vector (Promega), using the SacI and HindIII sites immediately downstream of the stop codon of the luciferase cDNA, generating pTwist1-3'UTR-luc, p15a-3p-MRE-WT-luc, p15a-3p-MRE-MT-luc, p16-1-3p-MRE-WT-luc and p16-1-3p-MRE-MT-luc respectively. The resulting plasmids are shown in Figure S4 in the Supplemental information section. Other plasmids used in this study, See Supplemental Materials and Methods section in Supplementary Information.

Cell culture and transient transfection

Human BGC823 gastric cancer cells were obtained from the ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA), and the cells were maintained in DMEM medium (Cat#12491-015, Gibco, Grand island, NY, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Cat#10099141, Gibco, Grand island, NY, USA) and incubated in a humidified incubator at 37 ºC in 5% CO2. Plasmid DNA, miRNA mimics and miRNA inhibitor (anti-sense oligonucleotides) transfections were performed with Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Cat#11668-019, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) analyses of mRNAs and miRNAs

For qPCR analyses of mRNA, reverse transcription was performed with TRIzol (Cat#15596-018, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA)-extracted total RNAs using a ReverTra Ace-α® Kit as instructed (Cat#FSQ-101, Toyobo, Tokyo, Japan). qPCR was performed using the SYBR Green Real-Time PCR Master Mix (Cat#QPK-212, Toyobo) and the Step One Plus Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems Inc., Foster City, CA, USA) using appropriate primer pairs as listed in Table S3, according to the manufacturers' protocols and with 18S rRNA as a control.

For miRNAs, qPCR was performed with the stem-loop primers as reported previously 31. U6 RNA served as an internal control. The miRNA-specific stem-loop primers listed in Table S3. qPCR was performed with total RNAs, using universal primer and miRNA-specific reverse LNA-primers as listed in Supplementary Table S3, with U6 RNA served as an internal control.

Western blot analyses

Cell protein lysates were separated in 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Amersham). The detection was achieved using the Immobilon Western Chemiluminescent HRP Substrate Kit (Cat#WBKLS0500, Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany). The antibodies used were listed on Table S4.

Luciferase reporter assays

Luciferase reporter activities were determined using a Luciferase Reporter Gene Assay System (Cat#E1601, Promega, Madison, WI, USA) as instructed. About 1 × 105 BGC823 cells were transfected with 10 pm of miR-15a-3p or miR-16-1-3p mimics and 0.3 μg of luciferase reporter plasmid together with 0.1 μg of pSV40-β-galactosidase (4:3:1) as indicated. Cells were harvested for luciferase activity assays 24 h after the transfection. The calibrated value for a proper control was used to normalize all other values to obtain the normalized relative luciferase units (RLU) representing the activities of the Twist1-3' UTR.

Gelatin- and casein-zymography analysis

About 5×105 BGC823 cells were seeded onto 6-well plates. After 24 hours, cells were transfected with 4 μg of pmiR-15a, pmiR-16-1 or the control plasmid. 24 hours after the transfection, the cell medium were collected and mixed with non-reducing SDS gel sample buffer and applied without boiling to a 10% polyacrylamide gel containing 0.1% SDS and 1 mg/ml gelatin or casein solution. After electrophoresis, the gels were washed in 50 mmol/l Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) containing 0.15 mol/l NaCl, 5 mmol/l CaC12, 5 μmol/l ZnCl, 0.02% NaN3, 0.25% Triton X-100 (three changes) at room temperature, and then incubated in the same buffer without Triton X-100 (two changes) at 37°C for 20 h. Proteins were stained by Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250 solution.

Cell migration, invasion and colony formation assays

For wound-healing assays, about 5×105 BGC823 cells were seeded onto 6-well plates. After 24 hours, cells were transfected with 2 μg of pmiR-15a, pmiR-16-1 or the control plasmid in the presence or absence of 2 μg of pHA-Twist1. After transfection, a wound was incised in the center of the confluent culture, followed by careful washing to remove detached cells and the addition of fresh medium. Phase contrast images of the wounded area were recorded using an inverted microscope at indicated time points.

Cell migration was analyzed by Transwell (Cat#3422, Corning, NY, USA) assays according to the manufacturer's instructions. Matrigel invasion assays were performed using Millicell inserts coated with matrigel (Cat#354480, BD Biosciences, Sparks, MD, USA). BGC823 cells were grown and transfected with pmiR-15a or pmiR-16-1 in the presence or absence of pHA-Twist1 as described before. 24 hours after the transfection, 2.5×104 BGC823 cells were seeded per upper chambers in serum-free DMEM whereas the lower chambers were loaded with DMEM containing 5% FBS. After 48 hours, the non-migrating cells on the upper chambers were removed by a cotton swab, and cells invaded through the matrigel layer to the underside of the membrane were stained with a 0.1% crystal violet solution and counted manually in eight random microscopic fields.

For colony formation assays, about 5×105 BGC823 cells were seeded onto 6-well plates. After 24 hours, cells were transfected with 4 μg of pmiR-15a, pmiR-16-1 or the control plasmid. 24 hours after the transfection, 200 of treansfected cells were seeded on six-well plates and maintained in DMEM containing 10% FBS for 2 weeks. Cells were fixed with methanol and stained with 0.5% crystal violet in 50% methanol for 1 hour and colonies larger than 100 μm in diameter were counted.

For soft agar colony formation assays, about 5×105 BGC823 cells were seeded onto 6-well plates. After 24 hours, cells were transfected with 2 μg of pmiR-15a, pmiR-16-1 or the control plasmid in the presence or absence of 2 μg of pHA-Twist1. 24 hours after the transfection, 5×103 transfected BGC823 cells were suspended in 2 ml of DMEM containing 0.3% agar and 10% serum and added onto a layer of medium containing 0.5% agar and 10% serum in a 6-well plate. 2 ml of medium containing 10% serum was added to the dish every other day. After 14 days, the number of colonies was measured.

Animal experiments

All experimental procedures involving animals were performed in accordance with animal protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee of Xiamen University. For xenograft tumor growth, BGC823 cells were infected with LV-miR-Ctrl, LV-miR-15a and LV-miR-16-1 lentivirus in the presence or absence of LV-Twist1. 24 hours after the infection, cells were harvested and suspended in PBS and then inoculated subcutaneously (~1 × 106 cells/100 ml/mouse) into the right side of the posterior flank of male BALB/c athymic nude mouse at 5 to 6 week. Beginning from the 7th day after the injection, the size of the tumor was measured every 3 days by a Vernier caliper along two perpendicular axes. Tumor volume (V) was monitored by measuring the length (L) and width (W) and calculated with the formula (L × W2) × 0.52. Twenty-five days after the injection, the mice were sacrificed and the tumors were dissected for further analyses.

Clinical samples

All clinical samples were collected with the informed consent of the patients and study protocols that were in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki (1975) and were approved by the Institutional Medical Ethics Committee of Xiamen University. GC pathological diagnosis was verified by at least two pathologists. Twenty human GC specimens and paired adjacent epithelial tissues were obtained from the Zhongshan Hospital affiliated to Xiamen University from 25 January 2014 to October 2014.

Other data acquisition, image processing and statistical analyses

Western blot images were captured by Biosense SC8108 Gel Documentation System with GeneScope V1.73 software (Shanghai BioTech, Shanghai, China). Gel images were imported into Photoshop for orientation and cropping. Data are the means ± SEM. One-way ANOVA with Bonferonni's post-test was used for multiple comparisons and the Student's t test (two-tailed) for pair-wise comparisons.

Results

Twist1 is a direct target of miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p

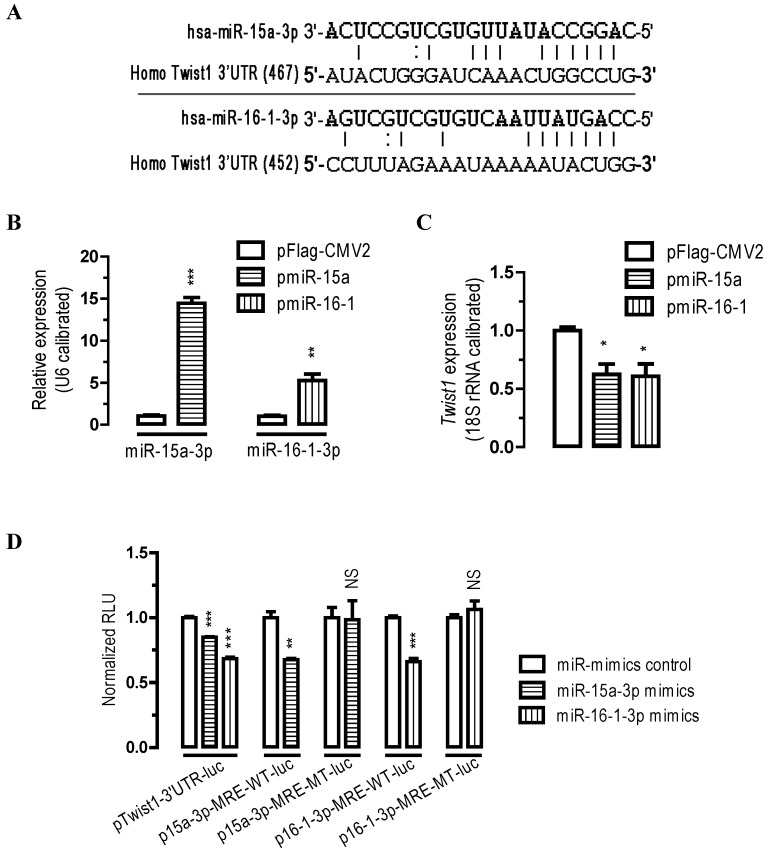

To identify the potential miRNAs that might target Twist1, we analyzed the 3' UTR sequence of human Twist1 with miRanda (http://www.microrna.org) algorithms. Our bioinformatics analysis suggested that there are two miRNA MREs on human Twist1 3'UTR (one MRE for miR-15a-3p and one MRE for miR-16-1-3p, Figure 1A), suggesting that these two miRNAs might be important regulators for Twist1.

Figure 1.

Twist1 is a direct target of miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p. (A) bioinformatic prediction of miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p recognition elements on the human Twist1-3' UTR. Analyses were performed with either the mirRanda algorithms. (B) transfection of pmiR-15a and pmiR-16-1 miRNA overexpression plasmids significantly increased miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p expression, respectively. BGC823 cells were transfected with pFlag-CMV2 or pmiR-15a or miR-16-1. 24 hours after the transfection, cells were harvested for qPCR analysis using miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p specific primers. n = 3, **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001. (C) overexpression of miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p significantly reduced the Twist1 mRNA expression level in BGC823 cells. (D) miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p regulate Twist1 by interacting with the 3' UTR of Twist1. BGC823 cells were transfected with miR-15a-3p or miR-16-1-3p mimics and a luciferase reporter plasmid together with pSV40-β-galactosidase (4:3:1) as indicated. Cells were harvested for luciferase activity assays 24 h after the transfection. β-galactosidase activity was determined and used for the calibration of luciferase reporter activity. Data are represented as the mean ± SEM (n = 3). NS, not significant; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

To determine whether miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p regulate Twist1 expression, we performed transient transfection studies in cultured BGC823 cells. Our quantitative PCR (qPCR) analyses indicated that, compared to the control transfected group (pFlag-CMV2-transfected group), transfection of BGC823 cells with a plasmid carrying miR-15a or miR-16-1 precursor (pmiR-15a or pmiR-16-1, see supplemental materials and methods) significantly increased miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p expression (p < 0.001 and p < 0.01, Figure 1B), and this induction of the miRNAs led to a 38% (p < 0.05) and 39% (p < 0.05) reduction in Twist1 mRNA expression, respectively (Figure 1C).

To further determine whether miR-15a-3p or miR-16-1-3p regulate Twist1 by targeting the Twist1-3' UTR, we performed 3' UTR luciferase reporter assays. Firstly we constructed Twist1-3' UTR-luciferase reporter plasmids (see supplemental materials and methods) and used them for BGC823 cell transfections. Plasmid pTwist1-3'UTR-luc contained a full-length sequence for human Twist1-3' UTR (Figure S4). BGC823 cells were co-transfected with miR-15a-3p mimics or with miR-16-1-3p mimics and luciferase reporter plasmid pTwist1-3'UTR-luc. Consistent with the bioinformatics prediction, transfection of miR-15a-3p or miR-16-1-3p mimics significantly caused a 15% (p < 0.001) or 32% (p < 0.001) reduction in luciferase activity in BGC823 cells cotransfected with pTwist1-3'UTR-luc, respectively (Figure 1D). These results suggest that miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p repress Twist1 through interacting with the MREs on its 3'UTR. Mutational analyses of the miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p MRE on Twist1-3' UTR (wildtype MRE plasmid p15a-3p-MRE-WT-luc and p16-1-3p-MRE-WT-luc versus mutated MRE plasmid p15a-3p-MRE-MT-luc and p16-1-3p-MRE-MT-luc) further confirmed the specific interaction between miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p and Twist1-3' UTR (Figure 1D). Together, these data suggest that Twist1 mRNA was all under the post-transcriptional control of miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p by target Twist1-3' UTR.

miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p repress Twist1 and EMT-related genes

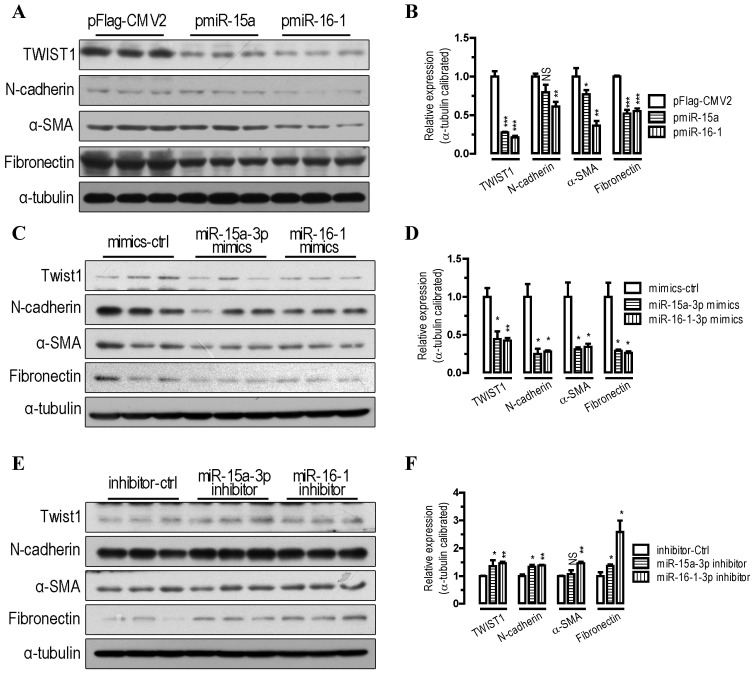

To further probe the function of miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p in the regulation of the EMT pathway, we performed transfections in BGC823 cells. Our Western blot analysis showed that overexpression of miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p significantly decreased TWIST1 protein level (p < 0.001, Figure 2A and 2B). With the overexpression of miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p in BGC823 cells, the EMT-related proteins, which include N-cadherin, α-SMA and Fibronectin were all significantly down-regulated compared with that of pFlag-CMV2-transfected cells (Figure 2A and 2B). Similarly to the results for miRNA overexpression, transfection with chemically synthesized miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p mimics significantly repressed TWIST1 and EMT-related protein expression (Figure 2C and 2D). Conversely, inhibition of miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p with an antisense inhibitor resulted in a dramatic increase in the protein level of TWIST1, N-cadherin, α-SMA and Fibronectin (Figure 2E and 2F). In addition, overexpression of miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p decreased the activity of MMP2 and MMP9 (Figure S1). Together, these results indicate that overexpression of miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p effectively suppressed the expression of TWIST1 and a group of EMT-related proteins, indicating that miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p can serve as key regulators involved in EMT process.

Figure 2.

miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p repress TWIST1 and EMT-related protein expression. (A and B) overexpression of miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p significantly repressed TWIST1, N-cadherin, α-SMA and Fibronectin protein expression. (C and D) transfection of miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p mimics significantly reduced TWIST1, N-cadherin, α-SMA and Fibronectin protein expression. (E and F) inhibition of miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p significantly induced TWIST1, N-cadherin, α-SMA and Fibronectin protein expression. BGC823 cells were transfected with miRNA expression plasmids, miRNA mimics or miRNA inhibitor as indicated. Cells were harvested for protein analysis 24 h after the transfection. α-tubulin was used for the loading control. Data are represented as the mean ± SEM (n = 3). NS, not significant; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

Overexpression of miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p suppress GC cell migration and invasion, whereas co-transfection of Twist1 ameliorated the loss of cell migration and invasion

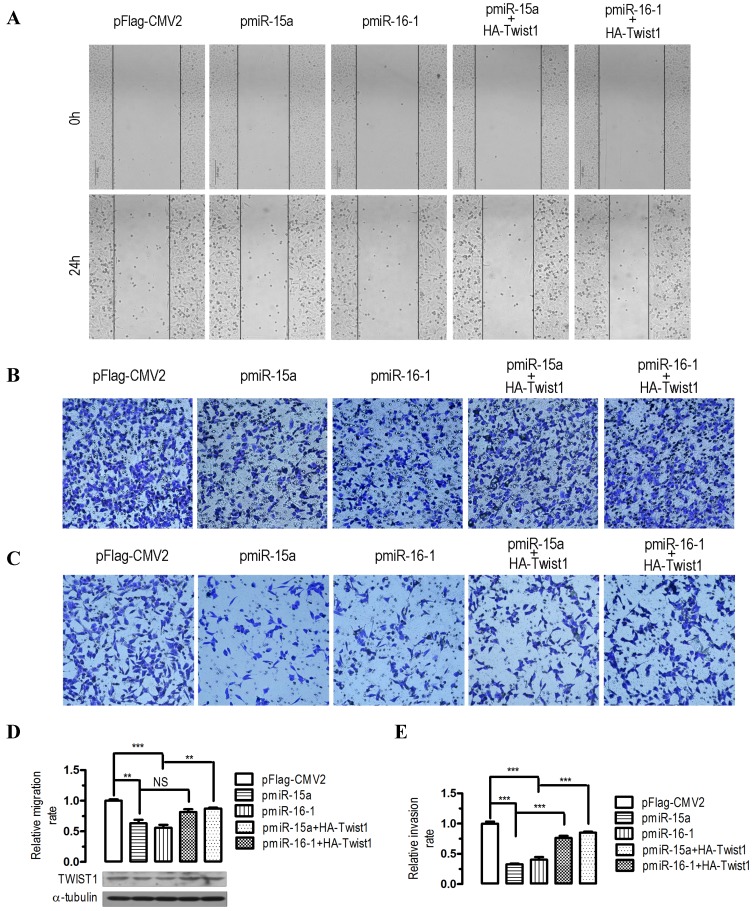

To evaluate the impact of miR-15a-3p- and miR-16-1-3p-mediated regulation of Twist1, we overexpressed miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p in BGC823 cells and performed wound healing and transwell experiments. In human BGC823 cells, overexpression of miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p greatly suppressed cell migration (Figure 3A), however, co-transfection with a HA-tagged Twist1 overexpressing plasmid significantly restored the inhibition of cell migration (Figure 3A). To further determine whether overexpression of miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p might affect cell migration and invasion, we performed transwell migration and invasion assays with BGC823 cells. In the transwell migration assays, we found that overexpression of miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p significantly decreased the ability of cells to migrate through the membrane by approximately 37% (p < 0.01) and 44% (p < 0.001, Figure 3B and 3D), respectively, whereas Twist1 co-transfection significantly ameliorated the inhibition of cell migration (Figure 3B and 3D). Similarly, overexpression of miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p significantly decreased the likelihood of cell invasion as determined by their ability to penetrate the Matrigel-coated membrane (p < 0.001, Figure 3C and 3E), and co-transfection of Twist1 rescued this cell invasion ability (Figure 3C and 3E). Together, these data suggest that miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p can serve as tumor suppressors of GC cell migration and invasion by regulating Twist1.

Figure 3.

Effects of overexpression of miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p in BGC823 cells on cell migration and invasion. For wound‑healing assay, BGC823 cells were seeded and transfected with pmiR-15a, pmiR-16-1 or the control plasmid in the presence or absence of pHA-Twist1. 24 hours after the transfection, wound healing was recorded in photographs. For the migration and invasion assay, about 5 × 105 BGC823 cells were grown and transfected with pmiR-15a or pmiR-16-1 in the presence or absence of pHA-Twist1 for 24 hours. Approximately 2.5 × 104 transfected BGC823 cells were plated in the upper chamber of an 8-μm Transwell insert (BD Biosciences). DMEM medium with 5% FBS (serum) was added to the bottom chamber. The rest of the transfected cells were collected for Western blot analysis. After 48 h, migrated and invaded cells were stained and counted. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM (n = 3). NS, not significant; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001. (A) overexpression of miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p significantly suppressed cell migration, while co-transfection with Twist1 significantly ameliorated the loss of cell migration, as determined in a wound‑healing assay. (B and D) overexpression of miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p significantly suppressed cell migration, while co-transfection with Twist1 significantly ameliorated the loss of cell migration in pmiR-15a or pmiR-16-1 transfected cells, as determined in a transwell assay. (C and E) overexpression of miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p significantly suppressed cell invasion, while co-transfection with Twist1 significantly ameliorated the loss of cell invasion in pmiR-15a or pmiR-16-1 transfected cells, as determined in a transwell assay.

miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p suppress colony formation in vitro

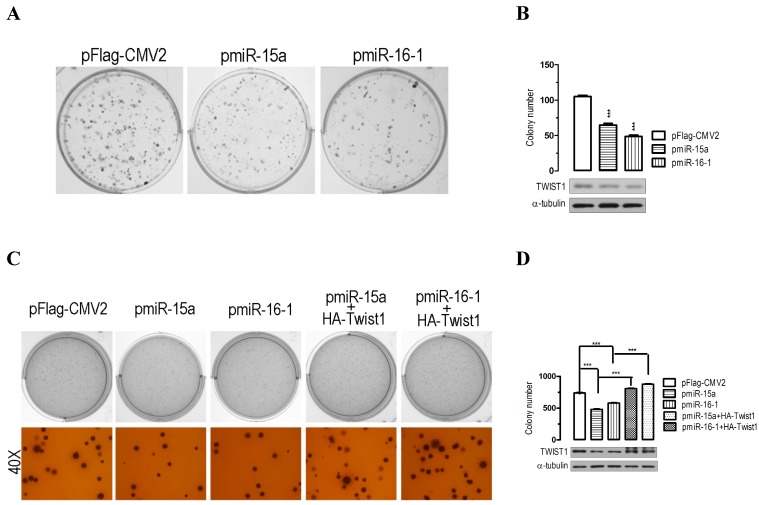

The significant suppression of migration and invasion by miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p expression prompted us to further explore the possible biological significance of miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p in tumorigenesis. As an initial step, the capacity for colony formation was evaluated in BGC823 cells that were transfected with miRNA overexpressing plasmids or control plasmid pFlag-CMV2. Interestingly, miR-15a- and miR-16-1-transfected cells displayed much fewer and smaller colonies compared with pFlag-CMV2-transfected cells (p < 0.001, Figure 4A and 4B). Additionally, a soft agar colony-forming assay was performed to measure anchorage-independent growth as a marker for the transforming potential of each clone. The soft agar colony formation assay showed that miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p overexpression significantly reduced the ability of soft agar colony formation relative to control vector-transfected cells (Figure 4C and 4D). Interestingly, cotransfection with a Twist1 overexpressing plasmid significantly rescued the suppression of colony formation ability in BGC823 cells (Figure 4C and 4D). Together, these results demonstrated that miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p inhibit cellular transformation by targeting Twist1.

Figure 4.

Overexpression of miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p significantly inhibits GC cell colony formation. (A and B) the effect of miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p on the colony formation of BGC823 cells. Representative results of colony formation of pFlag-CMV2-, pmiR-15a- and pmiR-16-1-transfected BGC823 cells. 24 hours after transfection, 200 transfected cells were placed in a fresh six-well plate and maintained in DMEM containing 10% FBS for 2 wk. The rest of the transfected cells were collected for Western blot analysis. Colonies were fixed with methanol and stained with 0.5% crystal violet in 50% methanol for 30 min. (C and D) overexpression of miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p significantly suppressed colony formation, while co-transfection with Twist1 significantly ameliorated the loss of cell colony formation, as determined in a soft agar assay. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM (n = 3). ***, p < 0.001.

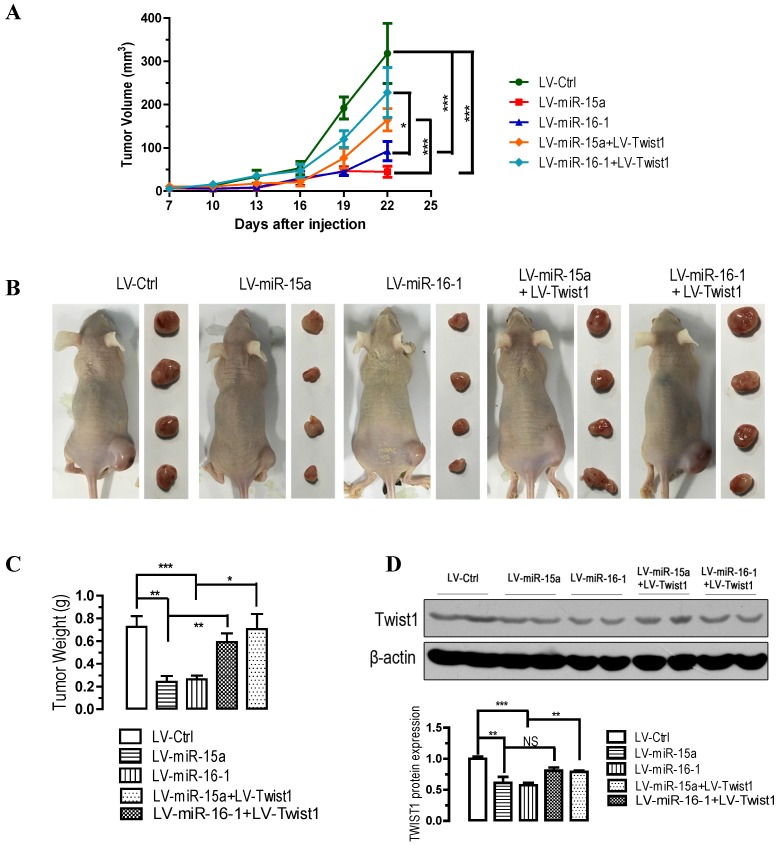

miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p suppress tumorigenicity in vivo, whereas Twist1 overexpression significantly ameliorated the loss of tumorigenicity in nude mice

To further confirm the above findings, an in vivo model was used. Lentivirus infected BGC823 cells (LV-miR-ctrl-, LV-miR-15a-, LV-miR-16-1-, LV-miR-15a+LV-Twist1- or LV-miR-16-1+LV-Twist1-infected BGC823 cells) were injected s.c. into the right posterior flank of nude mice. In nude mice, tumor growth of LV-miR-15a- and LV-miR-16-1-infected cells was much slower than that with LV-Ctrl-infected BGC823 cells (p < 0.001, Figure 5A), however, Twist1 overexpression significantly ameliorated the inhibition of tumorigenicity (p < 0.05 and p < 0.001, Figure 5A). The tumor became palpable from 7 to 10 days after inoculation and grew from average of 45 to 318 mm3 at the end of the observation. When dissected at the end of the study (day 25), the average tumor weight of the miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p overexpressed group were only 33.3% (p < 0.01) and 36.1% (p < 0.001) of that of the control group (Figure 5B and 5C). Co-infection of LV-Twist1, however, significant improved the tumor growth compared with LV-miR-15a- or LV-miR-16-1-infected group (p < 0.01 and p < 0.05, Figure 5B and 5C). In the miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p overexpressing tumor tissues, TWIST1 protein was greatly decreased (p < 0.01 and p < 0.001, Figure 5D). These results indicate that the introduction of miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p significantly inhibits tumorigenicity of BGC823 cells in a nude mouse xenograft model.

Figure 5.

Overexpression of miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p significantly inhibits tumor growth, while Twist1 ovexpression significantly ameliorated the loss of tumor growth in nude mice xenografted with GC cells. BGC823 cells were infected with LV-miR-Ctrl, LV-miR-15a and LV-miR-16-1 lentivirus in the presence or absence of LV-Twist1. 24 hours after the infection, cells were harvested and suspended in PBS and then inoculated subcutaneously (~1 × 106 cells/100 ml/mouse) into the right side of the posterior flank of 6-week-old nude mice. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM (n = 4). NS, not significant; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. (A) Time-dependent growth of xenograft tumor tissues in nude mice. (B) Tumor growth in nude mice 25 days after injection with LV-miR-ctrl-, LV-miR-15a-, LV-miR-16-1-, LV-miR-15a+LV-Twist1- or LV-miR-16-1+LV-Twist1-infected cells. (C) Comparison of tumor weights. (D) Altered expression of TWIST1 in dissected tumor tissues.

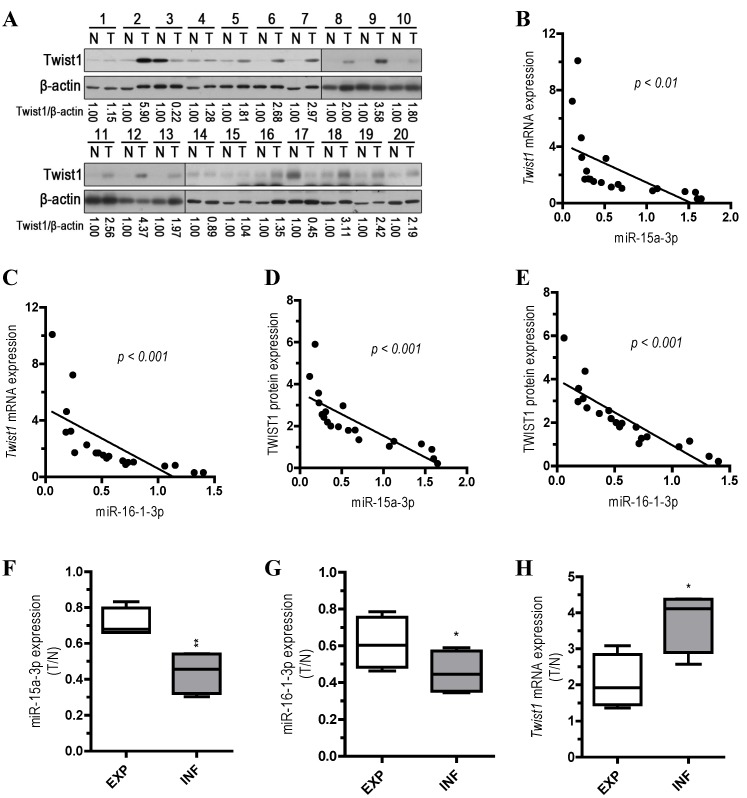

Inverse correlation between miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p expression and Twist1 mRNA and protein expression in GC clinical samples

To explore the relationship between the expression of miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p and the expression of Twist1 mRNA and protein, we performed qPCR and Western blots with 20 pairs of clinical samples. In approximately 70%~80% of the human GC tissues, miR-15a-3p (14 out of 20, Figure S2A) and miR-16-1-3p (16 out of 20, Figure S2B) were significantly down-regulated in comparison with controls, while Twist1 mRNA and protein expression levels were greatly increased (15 out of 20, Figure S2C and Figure 6A). Correlation analyses demonstrated significant inverse correlations between the expression of miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p and the expression of Twist1 mRNA (p < 0.01 and p < 0.001, Figure 6B and 6C) or protein (p < 0.001, Figure 6D and 6E) in the 20 pairs of GC samples tested. However, no apparent association was found between miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p expression with patient gender, patient age, tumor location, TNM staging or lymph node status (data not shown). We further analyzed the expression of miR15a-3p, miR-16-1-3p and Twist1 mRNA in two types of GC by Ming's classification 32. Remarkably, expression of miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p were lower in the infiltrative (INF) type of GC (p < 0.01 and p < 0.05, Figure 6F and 6G), while Twist1 mRNA were highly expressed in the INF type of GC compared to the expanding (EXP) type of GC (p < 0.05, Figure 6H). This result suggested that the down-regulation of miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p may affect the microenvironment of GC by targeting Twist1 to impact the invasion of tumor.

Figure 6.

Analysis of miR-15a-3p, miR-16-1-3p and Twist1 expression in GC samples. (A) Western blot demonstrating the protein expression level of TWIST1 in GC tissues. (B and D) inverse correlation between the expression of miR-15a-3p and the expression of Twist1 mRNA/protein in 20 pairs of GC clinical samples. (C and E) inverse correlation between the expression of miR-16-1-3p and the expression of Twist1 mRNA/protein in 20 pairs of GC clinical samples. (F) the expression level of miR-15a-3p in EXP and INF types of GC tissues. (G) the expression level of miR-16-1-3p in EXP and INF types of GC tissues. (H) the expression level of Twist1 in EXP and INF types of GC tissues. Abbreviations: T, GC tissue; N, adjacent noncancerous gastric tissue; 18S rRNA and U6 mRNA were calibrated for qPCR analysis; β-actin was used as a control for protein loading. EXP, expansive type of gastric cancer; INF, infiltrative type of gastric cancer.

Discussion

TWIST1, a member of the basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor family is an oncoprotein with important roles in the EMT process 33. Studies showed that Twist1 is overexpressed in a variety of human tumors and dysregulation of Twist1 has been associated with different types of cancers, and that Twist1 over-expression or down-regulation is correlated with tumor invasion and metastasis 20, 34, 35. A great number of studies reported the role of Twist1 in GC 36, 37. Quantitative real-time PCR analysis showed that Twist1 mRNA was overexpressed in diffuse-type adenocarcinoma 36. Yan-Qi et al. found that TWIST1 protein expression was significantly increased in diffuse-type gastric carcinoma and was correlated with lymph node metastasis in GC patients 37. However, the regulatory mechanisms underlying dysregulation of Twist1 were elusive. Here, we show that miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p repress the mRNA expression of Twist1 by interacting with the MREs on the 3' UTR. Consistent with previous studies, the expression of N-cadherin, α-SMA and Fibronectin 18, biomarkers of the EMT process, were down-regulated by Twist1 repression after the overexpression of miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p (Figure 2A, 2B, 2C and 2D). Furthermore, overexpression of miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p significantly suppressed migration and invasion, thereby suppressing the ability of BGC823 cells to form colonies in vitro, and suppressing their ability to develop tumors in vivo in nude mice. Importantly, our demonstration that inhibition of Twist1 by overexpression of miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p ameliorated GC development suggesting that miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p might be important therapeutic targets for prevention or treatment of GC and other EMT-associated cancers.

Several studies have found that abnormal expression of miRNAs was directly involved in the regulation of the genesis and development of GC 38-40. Microarray analysis showed that 22 miRNAs were up-regulated and 6 miRNAs were down-regulated in GC 38. Petrocca et al. found that the miR-106b-25 miRNA cluster is involved in E2F1 posttranscriptional regulation and may play a key role in the development of TGF-β resistance in GC 39. miR-21 was overexpressed in GC clinical samples and could serve as an efficient diagnostic marker for GC 40. In humans, miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p are members of the miR-15 miRNA cluster located at 13q14.3 41. Dynamic regulation of the expression of members of miR-15 cluster miRNAs is associated with B-cell development 41 in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), deletion of the normal allele 42, multidrug resistance in human GC cells 43 and B-cell abnormality in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) 44. Ectopic expression of miR-15a and miR-16-1 suppressed gastric cancer cell proliferation by targeting YAP1 protein expression to exert tumor suppressor function in gastric adenocarcinoma 45. A recent study also showed that miR-15a was significantly reduced in gastric cancer and inversely correlated with the protein expression of Bmi-1 46. Other evidence also suggests that the miR-15 cluster miRNAs can induce apoptosis by negatively regulating Bcl2 47. Aberrant immune and inflammatory responses represent key pathophysiological process that play important roles in the development of tumors 48. Interestingly, we found that miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p suppress EMT process by regulating Twist1, suggesting that the immune and inflammatory response can work together with tumor signaling pathways to influence tumor development.

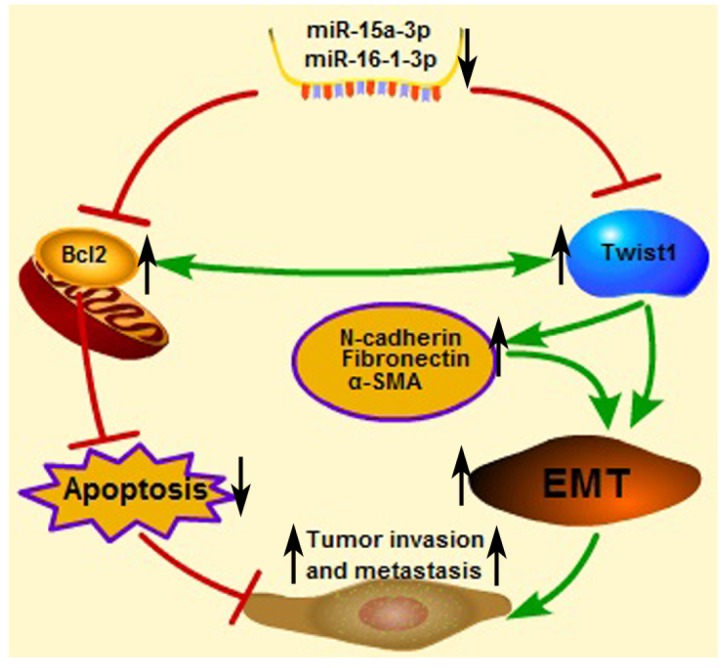

An important finding in this study is that miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p significant decreased in the expression in tumor samples taken from patients with GC compared to control biopsies of healthy tissue. Meanwhile, miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p were negatively corrected with Twist1 in GC samples. This result indicates that abnormal down-regulation of miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p contributed to EMT regulation in tumor invasion and metastasis. Interestingly, additional differences were discerned between expansive and infiltrative type of GC, with even lower amounts of the two miRNAs being present in the infiltrative type of GC. One possible explanation for this finding is that miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p can affect the microenvironment by regulating the EMT process. In a possible scenario (Figure 7), the abnormal down-regulation of miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p in GC induced the up-regulation of Twist1 and Bcl2, which, in turn, trigger the EMT process and suppress cell apoptosis respectively. Together, EMT promotion and apoptosis inhibition are both associated with tumor cell invasion and metastasis. These results suggest that miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p may play a role in the pathogenesis of GC, or at least serve as a marker of the condition. The expression levels of miR-15a-3p, miR-16-1-3p and Twist1 can provide the basis for the clinical diagnosis of GC. Our experiments demonstrate that miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p can severe as tumor suppressor genes, repressing the EMT process by targeting the Twist1 gene to inhibit the GC cell migration and invasion in vitro and in vivo. Therefore, we propose that the specific expression of miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p in tumor tissues rather than normal tissues is useful for the gene therapy of cancers.

Figure 7.

Proposed scheme for the roles of miR-15a-3p, miR-16-1-3p, Twist1, Bcl2 and other EMT related genes in tumor invasion and metastasis. The down-regulated mature miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p negatively regulate Twist1 expression. The up-regulated Twist1 would quickly induce the expression of N-cadherin, α-SMA and Fibronectin and so on. Together these genes promote the EMT process in GC and change the microenvironment to promote tumor invasion and metastasis. On the other hand, miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p negatively regulate the expression of anti-apoptotic gene Bcl2 47. The up-regulated Bcl2 would suppress GC cell apoptosis to promote tumor development. In addition in a previous study 49, Bcl2 could co-express with Twist1, therefore promote metastasis and inducing vasculogenic mimicry.

Taken together, our present findings have important implications for the elucidation of the pathogenic mechanisms underlying GC and for the clinical treatment of GC. Theoretically, the identification of this novel regulatory mechanism of Twist1 by miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p sheds light on the elucidation of pathogenic mechanisms involving the aberrant expression of miR-15a-3p, miR-16-1-3p and Twist1.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary figures and tables.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all members of the Prof. James Y. Yang laboratory for assistance. We would also like to thank Prof. Jiahuai Han from Xiamen University for providing the lentivirus packaging plasmids (pLV-EF1α-MCS-IRES-Puro, pMDL, pVSVG and pREV); Prof. Jianming Chen from Third Institute of Oceanography, State Oceanic Administration for providing HA tagged human Twist1-overexpressing plasmid pHA-Twist1.

Funding

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Science Foundation of China (#81172283, #81372616 and #31271239), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (#2013M531549), the National Science Foundation for Young Scientists of China (#81502035) and the Scientific Research Foundation of Third Institute of Oceanography, SOA (#2015011).

Abbreviations

- GC

gastric cancer

- EMT

epithelial-mesenchymal transition

- miRNA

microRNA

- MRE

miRNA recognition elements

- 3' UTR

3' untranslated region

- LV

Lentivirus

- mRNA

messenger RNA

- Bcl2

B-cell lymphoma 2

- MMP

metalloproteinase

- INF

infiltrative

- EXP

expanding

- WT

wild type

- MT

mutated type

- SEM

standard error of the mean.

References

- 1.Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:74–108. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.2.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Danaei G, Vander Hoorn S, Lopez AD, Murray CJ, Ezzati M. Causes of cancer in the world: comparative risk assessment of nine behavioural and environmental risk factors. Lancet. 2005;366:1784–93. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67725-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M. et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2012;136:E359–86. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nagini S. Carcinoma of the stomach: A review of epidemiology, pathogenesis, molecular genetics and chemoprevention. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2012;4:156–69. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v4.i7.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee YY, Derakhshan MH. Environmental and lifestyle risk factors of gastric cancer. Arch Iran Med. 2013;16:358–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang GL, Tao HR, Wang HW, Sun Y, Zhang LD, Zhang C. et al. Ara-C increases gastric cancer cell invasion by upregulating CD-147-MMP-2/MMP9 via the ERK signaling pathway. Oncol Rep. 2015;33:2045–51. doi: 10.3892/or.2015.3748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Townley-Tilson WH, Callis TE, Wang D. MicroRNAs 1, 133, and 206: critical factors of skeletal and cardiac muscle development, function, and disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2010;42:1252–5. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Javle M, Smyth EC, Chau I. Ramucirumab: successfully targeting angiogenesis in gastric cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:5875–81. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li X, Zhang Y, Zhang H, Liu X, Gong T, Li M. et al. miRNA-223 promotes gastric cancer invasion and metastasis by targeting tumor suppressor EPB41L3. Mol Cancer Res. 2011;9:824–33. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-10-0529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang D, Hendifar A, Lenz C, Togawa K, Lenz F, Lurje G. et al. Survival of metastatic gastric cancer: Significance of age, sex and race/ethnicity. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2011;2:77–84. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2078-6891.2010.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100:57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kalluri R, Weinberg RA. The basics of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1420–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI39104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thiery JP. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in tumour progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:442–54. doi: 10.1038/nrc822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Savagner P. Leaving the neighborhood: molecular mechanisms involved during epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Bioessays. 2001;23:912–23. doi: 10.1002/bies.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singh A, Settleman J. EMT, cancer stem cells and drug resistance: an emerging axis of evil in the war on cancer. Oncogene. 2010;29:4741–51. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thiery JP, Acloque H, Huang RY, Nieto MA. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in development and disease. Cell. 2009;139:871–90. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chaffer CL, Weinberg RA. A perspective on cancer cell metastasis. Science. 2011;331:1559–64. doi: 10.1126/science.1203543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shih JY, Yang PC. The EMT regulator slug and lung carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32:1299–304. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peinado H, Cano A. A hypoxic twist in metastasis. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:253–4. doi: 10.1038/ncb0308-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang J, Mani SA, Donaher JL, Ramaswamy S, Itzykson RA, Come C. et al. Twist, a master regulator of morphogenesis, plays an essential role in tumor metastasis. Cell. 2004;117:927–39. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kang Y, Massague J. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions: twist in development and metastasis. Cell. 2004;118:277–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feng MY, Wang K, Shi QT, Yu XW, Geng JS. Gene expression profiling in TWIST-depleted gastric cancer cells. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 2009;292:262–70. doi: 10.1002/ar.20802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sung CO, Lee KW, Han S, Kim SH. Twist1 is up-regulated in gastric cancer-associated fibroblasts with poor clinical outcomes. Am J Pathol. 2011;179:1827–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.06.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qian J, Luo Y, Gu X, Zhan W, Wang X. Twist1 promotes gastric cancer cell proliferation through up-regulation of FoxM1. PLoS One. 2013;8:e77625.. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077625. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–97. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136:215–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nelson KM, Weiss GJ. MicroRNAs and cancer: past, present, and potential future. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:3655–60. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ru P, Steele R, Newhall P, Phillips NJ, Toth K, Ray RB. miRNA-29b suppresses prostate cancer metastasis by regulating epithelial-mesenchymal transition signaling. Mol Cancer Ther. 2012;11:1166–73. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-12-0100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dong P, Kaneuchi M, Watari H, Sudo S, Sakuragi N. MicroRNA-106b modulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition by targeting TWIST1 in invasive endometrial cancer cell lines. Mol Carcinog. 2014;53:349–59. doi: 10.1002/mc.21983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li B, Han Q, Zhu Y, Yu Y, Wang J, Jiang X. Down-regulation of miR-214 contributes to intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma metastasis by targeting Twist. Febs J. 2012;279:2393–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2012.08618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raymond CK, Roberts BS, Garrett-Engele P, Lim LP, Johnson JM. Simple, quantitative primer-extension PCR assay for direct monitoring of microRNAs and short-interfering RNAs. Rna. 2005;11:1737–44. doi: 10.1261/rna.2148705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ming SC. Gastric carcinoma. A pathobiological classification. Cancer. 1977;39:2475–85. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197706)39:6<2475::aid-cncr2820390626>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martin A, Cano A. Tumorigenesis: Twist1 links EMT to self-renewal. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:924–5. doi: 10.1038/ncb1010-924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ansieau S, Morel AP, Hinkal G, Bastid J, Puisieux A. TWISTing an embryonic transcription factor into an oncoprotein. Oncogene. 2010;29:3173–84. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Puisieux A, Valsesia-Wittmann S, Ansieau S. A twist for survival and cancer progression. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:13–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosivatz E, Becker I, Specht K, Fricke E, Luber B, Busch R. et al. Differential expression of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition regulators snail, SIP1, and twist in gastric cancer. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:1881–91. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64464-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yan-Qi Z, Xue-Yan G, Shuang H, Yu C, Fu-Lin G, Fei-Hu B. et al. Expression and significance of TWIST basic helix-loop-helix protein over-expression in gastric cancer. Pathology. 2007;39:470–5. doi: 10.1080/00313020701570053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Volinia S, Calin GA, Liu CG, Ambs S, Cimmino A, Petrocca F. et al. A microRNA expression signature of human solid tumors defines cancer gene targets. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:2257–61. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510565103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Petrocca F, Visone R, Onelli MR, Shah MH, Nicoloso MS, de Martino I. et al. E2F1-regulated microRNAs impair TGFbeta-dependent cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis in gastric cancer. Cancer Cell. 2008;13:272–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chan SH, Wu CW, Li AF, Chi CW, Lin WC. miR-21 microRNA expression in human gastric carcinomas and its clinical association. Anticancer Res. 2008;28:907–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Calin GA, Dumitru CD, Shimizu M, Bichi R, Zupo S, Noch E. et al. Frequent deletions and down-regulation of micro- RNA genes miR15 and miR16 at 13q14 in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:15524–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242606799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Calin GA, Ferracin M, Cimmino A, Di Leva G, Shimizu M, Wojcik SE. et al. A MicroRNA signature associated with prognosis and progression in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1793–801. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xia L, Zhang D, Du R, Pan Y, Zhao L, Sun S. et al. miR-15b and miR-16 modulate multidrug resistance by targeting BCL2 in human gastric cancer cells. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:372–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ren D, Liu F, Dong G, You M, Ji J, Huang Y. et al. Activation of TLR7 increases CCND3 expression via the downregulation of miR-15b in B cells of systemic lupus erythematosus. Cell Mol Immunol. 2015 doi: 10.1038/cmi.2015.48. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kang W, Tong JH, Lung RW, Dong Y, Zhao J, Liang Q. et al. Targeting of YAP1 by microRNA-15a and microRNA-16-1 exerts tumor suppressor function in gastric adenocarcinoma. Mol Cancer. 2015;14:52. doi: 10.1186/s12943-015-0323-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu C, Zheng X, Li X, Fesler A, Hu W, Chen L. et al. Reduction of gastric cancer proliferation and invasion by miR-15a mediated suppression of Bmi-1 translation. Oncotarget. 2016;7:14522–36. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cimmino A, Calin GA, Fabbri M, Iorio MV, Ferracin M, Shimizu M. et al. miR-15 and miR-16 induce apoptosis by targeting BCL2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:13944–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506654102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Disis ML. Immune regulation of cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4531–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.2146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhao N, Sun BC, Zhao XL, Liu ZY, Sun T, Qiu ZQ. et al. Coexpression of Bcl-2 with epithelial-mesenchymal transition regulators is a prognostic indicator in hepatocellular carcinoma. Med Oncol. 2012;29:2780–92. doi: 10.1007/s12032-012-0207-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary figures and tables.