Abstract

Background and aims

Tinder is a very popular smartphone-based geolocated dating application. The goal of the present study was creating a short Problematic Tinder Use Scale (PTUS).

Methods

Griffiths’ (2005) six-component model was implemented for covering all components of problematic Tinder use. Confirmatory factor analyses were carried out on a Tinder user sample (N = 430).

Results

Both the 12- and the 6-item versions were tested. The 6-item unidimensional structure has appropriate reliability and factor structure. No salient demography-related differences were found. Users irrespectively to their relationship status have similar scores on PTUS.

Discussion

Tinder users deserve the attention of scientific examination considering their large proportion among smartphone users. It is especially true considering the emerging trend of geolocated online dating applications.

Conclusions

Before PTUS, no prior scale has been created to measure problematic Tinder use. The PTUS is a suitable and reliable measure to assess problematic Tinder use.

Keywords: Tinder, problematic use, CFA, geolocated, online dating, Griffiths model

Introduction

Online dating is not a new phenomenon. From those heterosexual American couples who met in 2009, one-fifth reported that they have first met online. It is approximately the same proportion of couples who met in bars and it is two times more than the number of couples who have met in college (Rosenfeld & Thomas, 2012). Furthermore, out of the 54 million single Americans, 41 million tried dating sites at least once. Slightly more men (52.4%) use it than women (47.6%). Annually, an average user spends 239 USD on online dating services. Consequently, the online dating industry has 1.2 billion USD of annual income (Statistic Brain Research Institute, 2015). It is not only prevalent in the USA; according to a Dutch study (Valkenburg & Peter, 2007), almost half of the respondents visited online dating sites to find a romantic partner and one-third of them had at least one profile on a dating site. More interestingly, 5.8% of these respondents created and used more than 5 profiles. However, since smartphones are able to use geolocation-based applications, a new era of online dating has emerged with Tinder being the leader of these applications.

Tinder is a dating smartphone application which uses the location of users to offer them potential dating partners. With the help of swiping motions on the screen, users can easily and quickly rate and reach a number of potential dating partners. A user only has to have a profile which is very basic: it consists of several photos and a short description of the user. Since it is connected to the individual’s Facebook profile, almost no effort is needed to create a Tinder profile. Users can either like (by swiping right) or dislike (by swiping left) a person. If both users swipe right, they are “matched” and can message each other. Tinder uses several innovations compared to classical dating sites: it is fast, casual and individuals do not have to make an effort to be “matched”. Moreover, on a classic online dating site, the feeling of rejection can be higher due to the lack of replies and the amount of efforts one has to make in order to find someone. On the basis of a recent worldwide (33 countries, aged between 16–64 years), non-representative research, among the 170,000 online users, 47,622 have used Tinder at least once in their life (Global Web Index, 2015 cited by McHugh, 2015).

According to qualitative studies (Masden & Edwards, 2015), due to the scarce information one can share and the fact that “matching” is the only possible feedback, norms of Tinder use can hardly emerge. However, from the perspective of users, mainly positive remarks appear on the Internet. One female user commented on Tinder in The Telegraph in the following way: “My sociopathic curiosity and appetite for constant validation is fueled by Tinder’s addictive function. I started consuming hundreds of profiles on boring journeys or in queues for a slow barista.” (Kent, 2015). Another female user mentioned the followings after intensive use of Tinder: “It was also a lot easier to spend all my time swiping right and left on my phone. The act of Tindering itself was addictive, the dating part was non-existent.” (Borkin, 2015). Besides these anecdotes, to our best knowledge, no prior quantitative study or questionnaire was made in order to measure problematic Tinder use.

In order to identify problematic Tinder use, the six-component model (Griffiths, 2005) was used which can distinguish between core elements of problematic Tinder use: (a) salience (Tinder use dominates thinking and behavior); (b) mood modification (Tinder use modifies/improves mood); (c) tolerance (increasing amounts of Tinder use are required); (d) withdrawal (occurrence of unpleasant feelings when Tinder use is discontinued); (e) conflict (Tinder use compromises social relationships and other activities); and (f) relapse (tendency for reversion to earlier patterns of Tinder use after abstinence or control). Therefore, the aim of the present paper was to create a reliable scale with acceptable factor structure that could measure problematic Tinder use.

Methods

Participants and procedure

The research was conducted with an online questionnaire system, the filling out lasted approximately three minutes. Participants were informed about the goal and the content of the study; their anonymity and the confidentiality of their answers were ensured. They were asked to check a box if they agreed to continue and participate. The first part of the questionnaire contained questions regarding demographic data, such as gender, age, and level of education. They were also asked about their relationship status, and respondents estimated the frequency of their Tinder use. The target group of the questionnaire was people who have used Tinder at least once in their lifetime, therefore, those individuals were excluded who agreed to participate but have never used Tinder before. The questionnaire was shared in social networking sites and in specific online groups related to Tinder.

The final sample consisted of 430 Hungarian respondents (Female = 243; 56.5%) who were aged between 18 and 51 (Mage = 22.53, SDage = 3.74). 290 of them (67.4%) live in the capital, 40 (9.3%) in county towns, 76 (17.7%) in towns, and 24 (5.6%) in villages. Concerning their level of education, 24 (5.6%) had a primary school degree, 307 (71.4%) had a high school degree, 99 (23.0%) of them had a degree in higher education. Concerning the relationship status of the respondents, 251 (58.4%) were single, 95 (22.1%) were fundamentally single but have casual relationships, and 84 (19.5%) were in a relationship. 50 (11.6%) respondents used Tinder more than once a day, 64 (14.9%) used it on a daily basis, 107 (24.9%) used it more than once a week, 68 (15.8%) used it weekly, 24 (5.6%) used it once every second week, 35 (8.1%) used it monthly, and 82 (19.1%) used it less than once a month. There were no missing data in the dataset, because with the above-mentioned questionnaire system, it is possible to have all questions as “required”. Moreover, at the end, participants were required to press the “submit” option in order to have their answers sent in; otherwise their responses were not registered.

Measures

The Problematic Tinder Use Scale (PTUS) was built upon the six-component concept of Griffiths (2005). The wording of the items is compatible with the wording of other questionnaires (Bergen Facebook Addiction Scale – Andreassen, Torsheim, Brunborg, & Pallesen, 2012; Bergen Work Addiction Scale – Andreassen, Griffiths, Hetland, & Pallesen, 2012; Bergen Shopping Addiction Scale – Andreassen et al., 2015) which are similarly based on the six-component model. In the present study, this new scale measures the six core elements of problematic Tinder use in terms of (a) salience, (b) tolerance, (c) mood modification, (d) relapse, (e) withdrawal, and (f) conflict. Two items were adapted for each factor to have a larger initial item pool, and then on the basis of the factor analysis, we selected one per factor in order to have a version that is short and has adequate factor structure and reliability. The items were translated according to the protocol of Beaton, Bombardier, Guillemin, and Ferraz (2000). Respondents had to answer using a 5-point scale (1 = Never; 2 = Rarely; 3 = Sometimes; 4 = Often; 5 = Always). Instead of calling it “addiction”, we used the term “problematic use”, because this paper was not intended to focus on health-related issues. Furthermore, this particular behavior might not be as prevalent and widespread as other types of problematic behaviors or addictions.

Statistical analysis

For descriptive analysis (e.g. calculating means, frequencies, and skewness-kurtosis values) we used SPSS version 22. For investigating the factor structure a series of confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) were conducted using Mplus 7.3 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012). Because of severe floor effect of the item scores in terms of skewness and kurtosis, we dealt with the items as categorical indicators and used the mean- and variance-adjusted weighted least squares estimation method (WLSMV; Finney & DiStefano, 2006). Multiple goodness of fit indices were taken into consideration based on Brown (2015): the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) with its 90% confidence interval, and test of close fit (CFit). The following thresholds were used when assessing whether a model had good or acceptable fit (Bentler, 1990; Brown, 2015; Browne & Cudeck, 1993; Hu & Bentler, 1999; Schermelleh-Engel, Moosbrugger, & Müller, 2003): CFI (≥ .95 for good, ≥ .90 for acceptable), TLI (≥ .95 for good, ≥ .90 for acceptable), RMSEA (≤ .06 for good, ≤ .08 for acceptable), and CFit (≥ .10 for good, ≥ .05 for acceptable).

Multiple reliability indices were observed. Cronbach’s alpha (with its 95% confidence interval) should be above .70 for acceptable and above .80 for good reliability (Nunnally, 1978). Additionally, composite reliability and inter-item correlations were also estimated. The former should have a value above .70 (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994), while the values of the latter should be between .15 and .50 (Clark & Watson, 1995).

Ethics

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest, Hungary. All subjects were informed about the studies they participated in and all provided informed consent.

Results

To carry out the analysis of the factor structure, first we tested the 12-item one-factor solution. Next, we tested several 6-item models by taking into consideration model fit indices, the distributions of the items and modification indices as well. Besides having good content validity, the aim was to have good item-level normality; therefore, we intended to keep those items which showed smaller floor effect.

Structural analysis

A series of confirmatory factor analyses were conducted on the PTUS in order to test alternative models. Besides the 12-item version, we wanted to create the final 6-item model which has relatively low floor effect and has good model fit indices and reliability. The comparison of the two models can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1.

Confirmatory factor analysis results of the Problematic Tinder Use Scale

| CFI | TLI | RMSEA [90% CI] | CFit | α [95% CI] | CR | IIC | |

| 12-item model | .94 | .93 | .09 [.08–.10] | .00 | .83 [.81–.85] | .93 | .34 |

| 6-item model | .98 | .97 | .06 [.02–.09] | .32 | .69 [.64–.73] | .83 | .30 |

Notes: CFI = comparative fit index; TLI = Tucker–Lewis index; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation with its 90% confidence interval; CFit = RMSEA’s test of close fit; α = Cronbach’s alpha with its 95% confidence interval; CR = composite reliability; IIC = mean inter-item correlation.

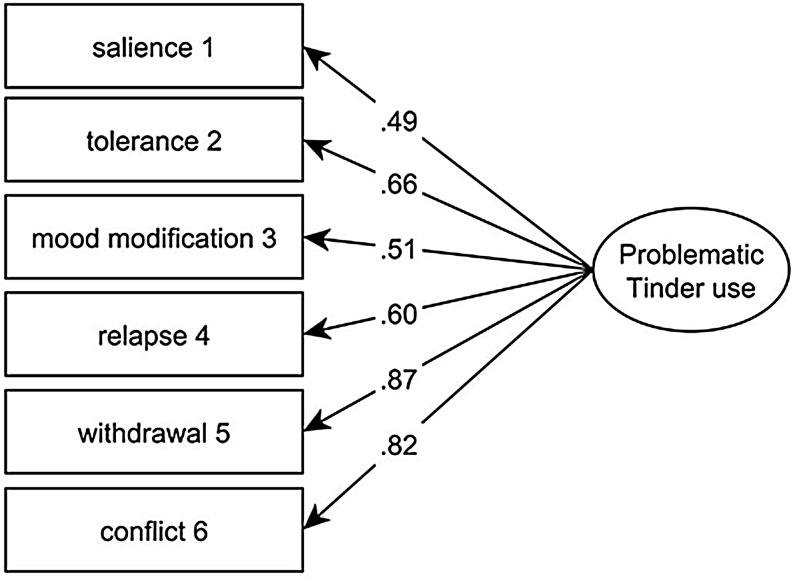

The results show that the 6-item model has acceptable model fit (CFI = .98; TLI = .97; RMSEA = .06 [90% CI .02–.09]; CFit = .32). Factor loadings ranged from .49 to .87 (see Figure 1). Although the Cronbach’s alpha value can be considered borderline (.69 [95%CI .64–.73]), both composite reliability (.83) and inter-item correlation scores (.30) were within the acceptable range, indicating that the PTUS has good factor structure and acceptable reliability.

Figure 1.

The final factor model of the Problematic Tinder Use Scale with standardized factor loadings. Notes: One-headed arrows between the latent and the observed variables represent the standardized regression weights. All loadings are significant at p < .001

Gender, age, relationship status, educational level and place of residence differences

The mean score of PTUS was (M = 11.38, SD = 3.33). PTUS scores correlated (Spearman) positively with the frequency of Tinder use [r(428) = .28, p < .001], but no link was found between PTUS scores and age. No gender differences were measured (Mfemale = 11.57, SDfemale = 3.45; Mmale = 11.13, SDmale = 3.15). Using one-way ANOVA (with Bonferroni-corrected post-hoc test), PTUS scores differed based on place of residence [F(3, 426) = 2.79, p = .04]: users living in the capital had higher scores (M = 11.67, SD = 3.37) than others living in county towns (M = 10.35, SD = 3.08), towns (M = 11.07, SD = 3.23), or villages (M = 10.54, SD = 3.18). In terms of relationship status, no differences were found between those who were single (M = 11.46, SD = 3.43), who were basically single with occasional relationships (M = 11.46, SD = 2.92) and those who were in a relationship (M = 11.05, SD = 3.47). Finally, in terms of educational level, no differences were measured between the groups.

Discussion

The present study intended to quantify problematic Tinder use. Based on Griffiths’ (2005) six-component model, a new 6-item scale was created which has acceptable reliability and factor structure. Although PTUS scores differed based on place of residence, no gender, educational level, and relationship status-related differences were found. Moreover, PTUS scores correlated positively although weakly with the frequency of Tinder use, but not with age. Among these findings, the relationship status-related results can be the most unexpected. It might be supposed that those who are in a relationship would have smaller scores than those who are single or those who are in occasional relationships. After examining this sample, the results suggest otherwise. It is possible that the mere act of “Tindering” – as in the quote in the introduction – can also be equally rewarding to those who are in stable relationships. These findings are in line with previous results in which 42% of the Tinder users were married or in a relationship (McGrath, 2015).

It is not obvious how to categorize problematic Tinder use. We can assume that it can have similar psychological background mechanisms to other problematic online behaviors (such as Internet, gaming or Facebook). However, the activity is much more specific. It is possible that “matches” can temporarily enhance self-esteem through positive feedbacks. It is also possible that it reduces the anxiety of those who have high rejection sensitivity thanks to the lack of explicit negative feedbacks. Another possible yet important aspect is the context of Tinder use. Several authors (de Timary & Philippot, 2015; Suissa, 2014; van der Linden, 2015) have claimed that it is important to investigate the social context of problematic behaviors and not just the person’s characteristics. There could be different contexts or life events in which Tinder use can become more prominent. For instance, in cases when someone experiences frequent rejection, or when (s)he is after a break-up, or when (s)he does not perceive his/her relationship satisfactory. Tinder use could increase if someone (e.g. a university student) moves to a new city without an already established social network. If these patterns emerged, Tinder could be the tool to compensate these shortcomings in one’s life and the probability of Tinder use becoming problematic could be higher.

Besides contextual triggers, several in-built characteristics of Tinder can contribute to the development of problematic behavior. Tinder has a fast and strong rewarding value, because individuals can get immediate social appreciation especially about their appearance in terms of positive feedbacks. The more time is spent on Tinder, the more positive feedback can be received. There is a practically limitless possibility of choices of potential dating partners which can make it harder to stop Tinder use. Small effort is needed for creating a profile and it is extremely easy to use this application on a smartphone. Users can see the closeness of the potential partners and in case of success; a relatively commitment-free immediate date can be the anticipated “reward”. These aspects of Tinder use can contribute to mood modification, salience, tolerance and relapse which are the main pillars of problematic use.

Recently, everyday activities have appeared in the framework of behavioral addictions which brings up the overpathologization hypothesis of Billieux, Schimmenti, Khazaal, Maurage, and Heeren (2015). It is clear that – similarly to other recently investigated topics like buying (Rodríguez-Villarino, González-Lorenzo, Fernández-González, Lameiras-Fernández, & Foltz, 2006), dancing (Maráz, Urbán, Griffiths, & Demetrovics, 2015), or studying (Atroszko, Andreassen, Griffiths, & Pallesen, 2015) – problematic Tinder use does not affect a large part of the population (Global Web Index, 2015 cited by McHugh, 2015). It should also be considered that such problematic behaviors do not have the same addictive potential as other substance-related behaviors might have (Potenza, 2015). If problematic Tinder use was to be considered addiction, several criteria would need to be established (e.g. clinical studies and evidence of life functions impairments). Apart from sexual problems, social impairments could also indicate an increase in Tinder use, such as a decrease in relationship satisfaction.

We suppose that problematic Tinder use could be considered as a separate entity from problematic Internet use. In the present case, Internet only serves as a medium through which users can access this service. However, the real aim of Tinder use is finding a partner in the above-described context and not to use the Internet in itself. Furthermore, Tinder is only available on smartphones (but not computers) and its specific goal is to match people, no other activity can be performed through this platform (i.e. browsing, watching videos, gaming or reading news). Nevertheless, we suppose that problematic Internet use and problematic Tinder use might not be independent from each other. Despite Tinder use is much more specific than Internet use, those who use the Internet excessively (i.e. have problematic Internet use) might become more easily problematic Tinder users. Future studies are needed to explore the relationship pattern between the two concepts.

This pioneering study has many limitations: regarding the measurement, it would be important to examine its temporal stability, convergent, divergent, and predictive validity. Despite the good model fit indices, good composite reliability, good inter-item correlations, the internal consistency of the PTUS is borderline. More detailed scales could more precisely grasp the dimensions of the problematic and non-problematic aspects of Tinder use. Instead of self-reported questions, behavior-related methods could be developed to measure one’s Tinder use that does not invade the individuals’ privacy. A longitudinal research design would be fruitful in order to investigate whether problematic Tinder use could have a negative impact on one’s health or could cause even minimal functional impairments. Moreover, a comprehensive sample could reveal the proportion of Tinder users among Internet users and the proportion of the problematic users among them. In a future study, a latent class analysis is needed on a larger sample to more precisely identify the characteristics of problematic Tinder users.

Conclusions

Considering the high number of Tinder users among Internet users (McHugh, 2015) and the increasing number of smartphone online daters (Goodman, 2014), Tinder – as a geolocated smartphone dating application – deserves the attention of scientific investigations. The goal of the present study was creating a short Problematic Tinder Use Scale (PTUS) based on Griffiths’ (2005) six-component model of addiction. Based on CFA, PTUS shows good factor structure and it has acceptable reliability. No salient demography-related differences were found, including the relationship status, as well. This pioneering study – despite its weaknesses – can fill the gap of quantitative research on the problematic use of geolocated dating applications.

Authors’ contribution

The first three authors (GO, ITK, BB) contributed equally to this paper in terms of literature review, data gathering, statistical analyses, and writing the paper. The last author (DM) contributed in terms of data gathering and statistical analyses. All four authors read the final version of the paper and participated in the creation of the final version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Bernadett Berkes for the additional data gathering.

Funding Statement

Funding sources: The first author was supported by the Hungarian Research Fund (NKFI PD 106027, 116686).

References

- Andreassen C. S., Griffiths M. D., Hetland J., Pallesen S. (2012). Development of a work addiction scale. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 3(53), 265–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9450.2012.00947.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreassen C. S., Griffiths M. D., Pallesen S., Bilder R. M., Torsheim T., Aboujaoude E. (2015). The Bergen Shopping Addiction Scale: Reliability and validity of a brief screening test. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1374. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreassen C. S., Torsheim T., Brunborg G. S., Pallesen S. (2012). Development of a Facebook addiction scale. Psychological Reports, 110(2), 501–517. doi: 10.2466/02.09.18.PR0.110.2.501-517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atroszko P. A., Andreassen C. S., Griffiths M. D., Pallesen S. (2015). Study addiction-A new area of psychological study: Conceptualization, assessment, and preliminary empirical findings. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 4(2), 75–84. doi: 10.1556/2006.4.2015.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaton D. E., Bombardier C., Guillemin F., Ferraz M. B. (2000). Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine, 25(24), 3186–3191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107(2), 238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billieux J., Schimmenti A., Khazaal Y., Maurage P., Heeren A. (2015). Are we overpathologizing everyday life? A tenable blueprint for behavioral addiction research. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 4(3), 119–123. doi: 10.1556/2006.4.2015.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borkin L. (2015). What I learned from my week-long addiction to Tinder. Hello Giggles. Retrieved on June 11, 2015 from http://hellogiggles.com/tinder-addiction

- Brown T. A. (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research (second edition). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Browne M. V., Cudeck R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In Bollen K. A., Long J. S. (Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 136–162). Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Clark L. A., Watson D. (1995). Construct validity: Basic issues in objective scale development. Psychological Assessment, 7(3), 309–319. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.7.3.309 [Google Scholar]

- De Timary P., Philippot P. (2015). Commentary on: Are we overpathologizing everyday life? A tenable blueprint for behavioral addiction research: Can the emerging domain of behavioral addictions bring a new reflection for the field of addictions, by stressing the issue of the context of addiction development? Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 4(3), 148–150. doi: 10.1556/2006.4.2015.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finney S. J., DiStefano C. (2006). Non-normal and categorical data in structural equation modeling. In Hancock G. R., Mueller R. D. (Eds.), Structural equation modeling: A second course (pp. 269–314). Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman E. (2014). Tinder sparks renewed interest in online dating category. ComScore. Retrieved on November 18, 2015 from https://www.comscore.com/Insights/Blog/Tinder-Sparks-Renewed-Interest-in-Online-Dating-Category

- Griffiths M. (2005). A ‘components’ model of addiction within a biopsychosocial framework. Journal of Substance Use, 10(4), 191–197. doi: 10.1080/14659890500114359 [Google Scholar]

- Hu L., Bentler P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118 [Google Scholar]

- Kent C. (2015). Tinder review: A woman’s perspective. The Telegraph. Retrieved on June 11, 2015 from http://www.telegraph.co.uk/men/relationships/10317832/Tinder-review-a-womans-perspective.html

- Maráz A., Urbán R., Griffiths M. D., Demetrovics Z. (2015). An empirical investigation of dance addiction. PLoS ONE, 10(5), e0125988. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masden C., Edwards W. K. (2015). Understanding the role of community in online dating. In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 535–544). ACM. doi: 10.1145/2702123.2702417 [Google Scholar]

- McGrath F. (2015). What to know about Tinder in 5 charts. GlobalWebIndex. Retrieved on November 2, 2015 from http://www.globalwebindex.net/blog/what-to-know-about-tinder-in-5-charts

- McHugh M. (2015). 42 percent of Tinder users aren’t even single. Wired. Retrieved on June 11, 2015 from http://www.wired.com/2015/05/tinder-users-not-single/

- Muthén L. K., Muthén B. O. (1998–2012). Mplus user’s guide. Seventh edition Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally J. C. (1978). Psychometric theory (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally J. C., Bernstein I. H. (1994). Psychometric theory (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Potenza M. N. (2015). Commentary on: Are we overpathologizing everyday life? A tenable blueprint for behavioral addiction research: Defining and classifying non-substance or behavioral addictions. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 4(3), 139–141. doi: 10.1556/2006.4.2015.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Villarino R., González-Lorenzo M., Fernández-González Á., Lameiras-Fernández M., Foltz M. L. (2006). Individual factors associated with buying addiction: An empirical study. Addiction Research & Theory, 14(5), 511–525. doi: 10.1080/16066350500527979 [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld M. J., Thomas R. J. (2012). Searching for a mate the rise of the Internet as a social intermediary. American Sociological Review, 77(4), 523–547. doi: 10.1177/0003122412448050 [Google Scholar]

- Schermelleh-Engel K., Moosbrugger H., Müller H. (2003). Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods of Psychological Research Online, 8(2), 23–74. [Google Scholar]

- Statistic Brain Research Institute (2015). Online dating statistics. Retrieved on June 11, 2015 from http://www.statisticbrain.com/online-dating-statistics/

- Suissa A. J. (2014). Cyberaddictions: Toward a psychosocial perspective. Addictive Behaviors, 39, 1914–1918. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.07.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valkenburg P. M., Peter J. (2007). Who visits online dating sites? Exploring some characteristics of online daters. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 10(6), 849–852. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2007.9941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Linden M. (2015). Commentary on: Are we overpathologizing everyday life? A tenable blueprint for behavioral addiction research: Addictions as a psychosocial and cultural construction. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 4(3), 145–147. doi: 10.1556/2006.4.2015.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]