Abstract

The study by Gomez et al., “The Fate of Spacers in the Treatment of Periprosthetic Joint Infection,” evaluates the clinical course and success rate of treatment of periprosthetic joint infection with two-stage revision with spacer placement in the interim period. The current review critically analyzes the findings of this study and examines how these findings may influence patient care in the field of hip and knee replacement. Gomez et al. report sobering results of two-stage revision with spacer placement for periprosthetic joint infection. Nearly 20% of patients in their study who had a spacer placed never went on to get a new prosthesis and nearly 20% of those who did get a new prosthesis ultimately failed treatment. The authors reported a 7.5% mortality rate in the interstage period after resection arthroplasty. This study provides valuable information for counseling patients about the outcomes of treatment using spacers for infection after total joint arthroplasty. The results of this study also highlight the need for future investigation into better treatments for periprosthetic joint infections.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11420-016-9507-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: periprosthetic joint infection, spacer, arthroplasty infection

Introduction

An estimated one million total hip and knee replacement surgeries are performed annually in the USA, and that number is projected to increase in coming years [10]. The incidence of periprosthetic hip and knee infection has been reported as greater than 2% in the Medicare population [1], with a reported economic burden of $566 million in the USA in 2009 [11].

Periprosthetic joint infection is a devastating complication of joint arthroplasty and is known to diminish quality of life in patients who suffer from this problem [7]. The vast majority of surgeons in North America treat periprosthetic infections using a two-stage exchange arthroplasty involving removal of primary implants and placement of an antibiotic spacer, followed by reimplantation of new prosthesic components at a later date. In the interim period, patients also typically are treated with 6 weeks of parenteral antibiotics and require close follow-up [13]. A one-stage (direct exchange) method is more commonly employed by European surgeons and involves removal of infected implants, debridement of nearby tissue, and implantation of new sterile implants all in one operation.

The article discussed here by Gomez et al. [4] described the outcomes of treatment of periprosthetic joint infection with planned two-stage exchange arthroplasty. The authors examined success rates and reasons for failure of eradication of periprosthetic joint infection. The aims of the current review are (1) to critically evaluate the findings presented in this study and (2) to examine how these findings may influence patient care in the field of total joint replacement.

The Article

The Fate of Spacers in the Treatment of Periprosthetic Joint Infection. Gomez MM, Tan, TL, Manrique, J, Deirmengian GK, Parvizi J. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97:1495–502.

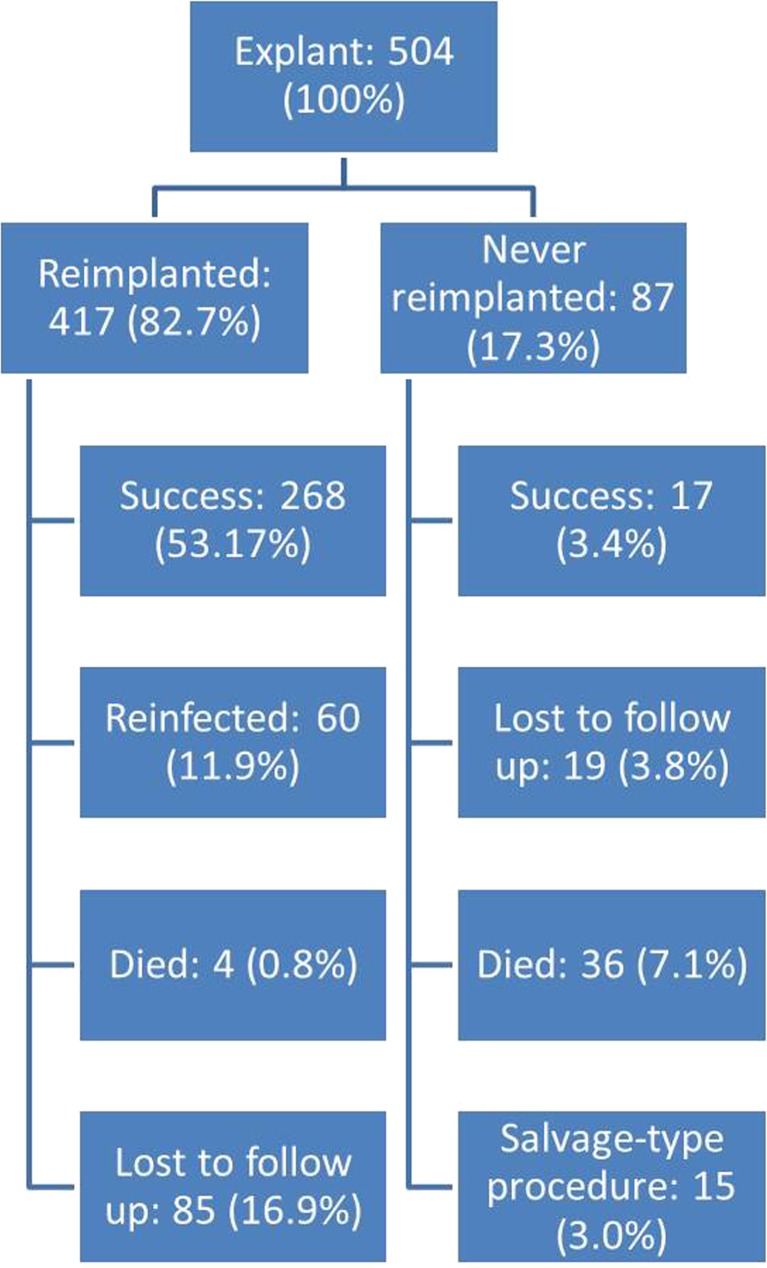

This study sought to answer the following research question: What is the clinical course and success rate of treatment of periprosthetic joint infection with two-stage revision in arthroplasty patients? To answer this question, the authors conducted a retrospective review from an institutional database of patients diagnosed with a periprosthetic hip or knee infection who underwent resection arthroplasty and antibiotic spacer placement for treatment. The study population included 482 patients (504 joints) treated between 1999 and 2013 (Figs. 1, 2, and 3). Almost all patients were treated with a spacer containing dual antibiotics to act against both gram-positive and gram-negative organisms. Notably, the cohort had a reported prevalence of diabetes of 22.8% and prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis of 8.7%.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of all patients treated for periprosthetic joint infection.

Fig. 2.

Flowchart of patients treated for periprosthetic hip infection.

Fig. 3.

Flowchart of patients treated for periprosthetic knee infection.

Four hundred seventeen cases (82.7%) underwent reimplantation of a new prosthesis as part of the two-stage treatment process. Of patients treated with reimplantation, treatment was successful in 81.4%. Eighty-seven cases retained their spacer, and of those, 23.6% were considered to be successfully treated. Classification of successful treatment included infection eradication characterized by a healed wound without drainage, fistula, or pain and no infection recurrence, no occurrence of periprosthetic joint infection-related mortality, and no subsequent surgical intervention for infection after reimplantation surgery. Sixty cases (11.9%) required a second spacer due to persistent infection, spacer dislocation, wound problems, or tibia fracture. Thirty-six of 482 patients (7.5%) included in the study died in the interstage period after resection arthroplasty. The most common organisms implicated in infection were coagulase-negative staphylococcus (16.7%), vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus or methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (14.9%), and methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (14.5%). Twenty-seven percent of cases treated in this study had negative cultures.

Commentary

Gomez et al.’s study is a valuable contribution to the literature regarding the clinical course of two-stage revision for treatment of periprosthetic hip and knee infections [4]. Previous studies have reported >90% rate of success of two-stage revision for periprosthetic infections [8, 12, 17, 18]. This study, however, provides sobering evidence that the outcomes of two-stage revision may be less successful than previously thought, with nearly 20% of patients undergoing resection arthroplasty while never getting a new prosthesis and nearly 20% of those who get a new prosthesis failing treatment.

This study has several strengths. First, it includes a large cohort of patients with close follow-up. It includes results for patients who were treated with the full two-stage course of revision, as well as patients who retained their spacer. This latter inclusion is important because prior studies may have reported overly inflated success rates by only including patients who were able to undergo both stages of treatment, while excluding patients who were unable to undergo the second stage [2, 15]. By including all patients who were started on the two-stage revision treatment pathway, the authors provide a more accurate picture of the outcomes, rather than skewing the results positively. Furthermore, this study includes patients treated at a high-volume joint replacement center with significant experience in treating periprosthetic joint infections. However, this setting of the study may have potential to introduce bias in that the institution may be a referral center for more complex infections than those treated in the general population.

Another strength of this study is that it provides data on the most relevant comorbidities, which are rheumatoid arthritis and diabetes mellitus. The authors found a significantly lower reimplantation rate in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, which may be an important consideration in counseling patients with this condition who require treatment for periprosthetic joint infection.

Nevertheless, this study also has shortcomings. First, as the authors concede in the manuscript, no functional outcomes were included in the results of this study. Functional outcomes may be relevant in weighing the risk and benefits of treatment of periprosthetic joint infections with long-term antibiotic suppression versus one-stage revision versus two-stage revision. Prior studies have suggested poor functional outcomes after two stage-revision [3], and functional outcome data from this study could have been relevant for patient counseling and surgical decision making. Furthermore, no general health or health-related quality of life metrics were reported in the study. This type of data could be particularly useful in evaluating treatment options, especially from a comparative health care policy standpoint. Second, the data came from a heterogeneous database of patients treated by a multitude of different surgeons with a variety of practices for treating periprosthetic joint infection. Therefore, it is possible that not every patient included in the study received the optimal treatment course, and this may have biased the results and contributed to the high treatment failure rate. Third, the majority of patients in this cohort were treated with nonarticulating spacers. Thus, it is unknown if patients treated with articulating spacers would have equally sobering results. While prior reviews have failed to demonstrate a significant difference in reinfection rates or functional scores for articulating versus nonarticulating spacers [14, 16], the outcomes of treatment with articulating spacers is an area requiring future investigation.

This study failed to address the differences in outcomes of periprosthetic joint infection between hips and knees. In the dataset, 65% of the infections are knees. It is unclear if this number reflects a higher rate of periprosthetic joint infection in knees compared to hips that require treatment with two-stage revision or if it is based on the referral patterns at the hospital where the study was performed. Unfortunately, statistics are not calculated to reflect differences between hips and knees in terms of outcome of periprosthetic joint infection treatment. However, further study is needed to define the differences and to develop specific protocols tailored to hip versus knee infections.

The results of this study show poorer outcomes than some of the previous reports of two-stage revisions for periprosthetic infections [8, 12, 17, 18]. These findings have significant implications for hip and knee arthroplasty surgeons. First, it is important for arthroplasty surgeons to be aware of the prognosis of patients who present with periprosthetic joint infection and to be able to counsel them appropriately. Second, this study demonstrates the need for better evidence-based protocols for treating periprosthetic joint infections. While two-stage revision has long been the gold standard, this and other recent studies call into question whether it is the best method of treatment. Recent studies have demonstrated the success of one-stage revision in selected patients [5, 9], and recent commentary has called for further research that seeks to expand the indications for one-stage revision to a broader group of patients with periprosthetic joint infections [6]. The results of the present study may serve to amplify the call for better solutions to the devastating problem of periprosthetic joint infections.

In conclusion, the study by Gomez et al. provides important information about the prognosis of patients undergoing two-stage exchange arthroplasty for treatment of periprosthetic infection and also reignites the debate about best treatment methods for this condition.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

(PDF 1225 kb)

(PDF 1224 kb)

(PDF 1224 kb)

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

Cynthia A. Kahlenberg, MD, and Alexia Hernandez-Soria, MD, have declared that they have no conflict of interest. Michael B. Cross, MD, reports personal fees from Acelity, Exactech, Inc., Intellijoint, Link Orthopaedics, Smith & Nephew; editorial/governing board of Journal of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, Bone and Joint Journal 360 and Techniques in Orthopaedics, outside the work.

Human/Animal Rights

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by the any of the authors.

Informed Consent

N/A.

Required Author Forms

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the online version of this article.

References

- 1.AAOS . The diagnosis of periprosthetic joint infections of the hip and knee: guideline and evidence report. Rosemont: AAOS; 2010. p. 277. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berend KR, Lombardi AV, Jr, Morris MJ, et al. Two-stage treatment of hip periprosthetic joint infection is associated with a high rate of infection control but high mortality. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471:510–518. doi: 10.1007/s11999-012-2595-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boettner F, Cross MB, Nam D, et al. Functional and emotional results differ after aseptic vs septic revision hip arthroplasty. HSS J. 2011;7:235–238. doi: 10.1007/s11420-011-9211-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gomez MM, Tan TL, Manrique J, et al. The fate of spacers in the treatment of periprosthetic joint infection. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97:1495–1502. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.N.00958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haddad FS, Sukeik M, Alazzawi S. Is single-stage revision according to a strict protocol effective in treatment of chronic knee arthroplasty infections? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473:8–14. doi: 10.1007/s11999-014-3721-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanssen AD. CORR Insights(R): is single-stage revision according to a strict protocol effective in treatment of chronic knee arthroplasty infections? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473:15–16. doi: 10.1007/s11999-014-3799-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Helwig P, Morlock J, Oberst M, et al. Periprosthetic joint infection--effect on quality of life. Int Orthop. 2014;38:1077–1081. doi: 10.1007/s00264-013-2265-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hsieh PH, Shih CH, Chang YH, et al. Two-stage revision hip arthroplasty for infection: comparison between the interim use of antibiotic-loaded cement beads and a spacer prosthesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A:1989–1997. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200409000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ilchmann T, Zimmerli W, Ochsner PE, et al. One-stage revision of infected hip arthroplasty: outcome of 39 consecutive hips. Int Orthop. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Inpatient Surgery. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/inpatient-surgery.htm. Accessed 31 Oct 2015.

- 11.Kurtz SM, Lau E, Watson H, et al. Economic burden of periprosthetic joint infection in the United States. J Arthroplast. 2012;27:61–65. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2012.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Macheras GA, Kateros K, Galanakos SP, et al. The long-term results of a two-stage protocol for revision of an infected total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br Vol. 2011;93:1487–1492. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.93B11.27319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parvizi J, Adeli B, Zmistowski B, et al. Management of periprosthetic joint infection: the current knowledge: AAOS exhibit selection. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94:e104. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.K.01417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pivec R, Naziri Q, Issa K, et al. Systematic review comparing static and articulating spacers used for revision of infected total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplast. 2014;29:553–557. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2013.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Toulson C, Walcott-Sapp S, Hur J, et al. Treatment of infected total hip arthroplasty with a 2-stage reimplantation protocol: update on “our institution’s” experience from 1989 to 2003. J Arthroplast. 2009;24:1051–1060. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Voleti PB, Baldwin KD, Lee GC. Use of static or articulating spacers for infection following total knee arthroplasty: a systematic literature review. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95:1594–1599. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.01461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Volin SJ, Hinrichs SH, Garvin KL. Two-stage reimplantation of total joint infections: a comparison of resistant and non-resistant organisms. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;94–100. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Yamamoto K, Miyagawa N, Masaoka T, et al. Clinical effectiveness of antibiotic-impregnated cement spacers for the treatment of infected implants of the hip joint. J Orthop Sci. 2003;8:823–828. doi: 10.1007/s00776-003-0722-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 1225 kb)

(PDF 1224 kb)

(PDF 1224 kb)