Abstract

Background

There is little data on whether preexisting allergies to implant materials and bone cement have an impact on the outcome of TKA.

Questions/Purposes

This review article analyzes the current literature to evaluate the prevalence and importance of metal and cement allergies for patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty.

Methods

A review of the literature was performed using the following search criteria: “knee,” “arthroplasty,” and “allergy” as well as “knee,” “arthroplasty,” and “hypersensitivity.”

Results

One hundred sixteen articles were identified on PubMed, Seventy articles could be excluded by reviewing the title and abstract leaving 46 articles to be included for this review. The majority of the studies cited patch testing as the gold standard for screening and diagnosis of hypersensitivity following TKA. There is consensus that patients with self-reported allergies against metals or bone cement and positive patch test should be treated with hypoallergenic materials or cementless TKA. Treatment options include the following: coated titanium or cobalt-chromium implants, ceramic, or zirconium oxide implants.

Conclusion

Allergies against implant materials and bone cement are rare. Patch testing is recommended for patients with self-reported allergies. The use of special implants is recommended for patients with a confirmed allergy.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11420-016-9514-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: allergy, total knee arthroplasty, oxinium, patch test

Introduction

The first reports of loosening after joint replacement caused by hypersensitivity or allergic reactions to metallic implants were published in the mid 70s and 80s [14, 19, 20, 67] and concerned hip arthroplasties with metal-on-metal bearings. More recently, there has been a trend towards studies examining allergies in metal on plastic total knee arthroplasties [14, 43].

The hypothesis that cutaneous and systemic hypersensitivity reactions develop in patients following total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is supported by studies showing a higher prevalence of positive patch tests after implantation of metallic TKA components [2, 6, 17, 22, 25, 51]. The higher sensitization to metal (in particularly nickel (Ni), chromium (Cr), and cobalt (Co)) might be caused by wear or corrosion. Although a positive patch test shows a strong correlation, no causal relationship has been established between dermal reactions and implants failure [62].

The “National Joint Replacement Registry of Australia” [3] notes “metal related pathology” in 1.8% and “undefined pain” in 9.2% of patients undergoing revision TKA. The overall revision rate was 3.45% after 10 years in 396.472 TKAs suggesting a revision rate of 0.06–0.32% secondary to metal or cement allergies. Still, these numbers are rather small and the role of allergies in total knee failures remains a controversial issue.

This review article analyzes the current literature to answer the following questions: (1) Can patients with an increased risk of implant allergy be recognized before surgery? (2) Is there a correlation between the presence of metal or bone cement hypersensitivity and implant failure? (3) Can the current literature be used to establish a treatment algorithm for patients with hypersensitivity to metal or bone cement undergoing TKA? (4) What treatment options are available for patients with an established metal allergy?

Methods

The search was limited to “PubMed” (www.pubmed.gov). The search criteria included the words “allergy,” “hypersensitivity,” “knee,” and “arthroplasty”. Two searches were performed: (a) “allergy,” “knee,” and “arthroplasty”; (b) “hypersensitivity” “knee” and “arthroplasty”. One hundred sixteen articles were identified. Seventy articles were excluded after reviewing the title and abstract (some exclusion criteria: other joints than knee, allergic reaction to medication during surgery, infection, antibiotics, metallosis, and allergic reaction to suture material after surgery). Forty-six articles were included in the review: 17 case reports (Table 1), 4 reviews [5, 15, 42, 43], 16 retrospective articles [11, 17, 19, 26, 32, 33, 35, 41, 45, 46, 48, 51, 52, 54, 61, 63], 8 prospective articles [2, 8, 10, 22, 25, 40, 47, 69], and one “expert opinion” [39].

Table 1.

Summary of case reports

| Author | Number of implants | Diagnostics | Implant | Revision | Histopathology | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patch test | LTT | |||||

| Anand 2009 [1] | 1 | Ni, Co | – | CoCr (Zimmer) | Titanium (Biomet) | Mononuclear infiltrate (lymphocytes, plasma cells, and macrophages) |

| Beecker 2009 [7] | 2 | Ni, Co | – | CoCr | – | – |

| Bergschmidt 2012 [9] | 1 | Ni, palladium | – | CoCr | Ceramic, titanium | Lymphoplasma cellular fibrinous tissue, type IV allergic reaction |

| Dietrich 2009 [16] | 4 | Ni, Co | Ni, Co | CoCrMb | Titanium | – |

| Edwards 2007 [18] | 1 | Benzoyl peroxide | – | – | Cementless | – |

| Gao 2011 [24] | 1 | Cr | – | CoCrMb | Oxinium® | – |

| Haeberle 2009 [27] | 1 | Gentamicin | – | – | – | – |

| Handa 2003 [29] | 1 | Co, copper | – | Copper, Cr | – | – |

| Kaplan 2002 [34] | 1 | Bone cement (preoperatively) | – | cementless | – | – |

| Schuh 2006 [55] | 1 | Benzoyl peroxide, Ni | – | – | – | – |

| Thakur 2013 [58] | 5 | 1. No test 2. Co 3. Co 4. No test 5. Negative |

– | 1.–5. CoCr | 1.–5. Oxinium® | Periprosthetic lymphohistiocytic infiltrates in 3/5 patients |

| Thienpont 2013 [59] | 1 | CoCr | – | CoCr | – | – |

| Post 2013 [49] | 1 | Co, Cr, Ni | Cr | CoCr | Oxinium® | – |

| van Opstal [65] | 1 | Negative | – | TiAlVa | Zirconium alloy tibial baseplate | – |

| Verma 2006 [66] | 15 | Ni (4), Cr (2), Co (1) | – | CoCr | – | – |

| Thomsen 2011 [62] | 1 | – | Negative | CoCr | Multilayer coated | – |

Results

(1) Patch tests were used to confirm a suspicion for an implant or bone cement allergy in 15 of the 17 case reports reviewed [1, 7, 9, 16, 18, 24, 27, 29, 34, 49, 55, 58, 59, 65, 66]. In only three case reports “lymphocyte transformation test” (LTT) was used [16, 49, 62]. Other diagnostic methods were not described in any of the 17 case reports. Thirty-nine patients were included in those 17 case reports. Eleven patients showed a positive skin test against nickel (Ni), 9 patients against cobalt (Co), 5 against chromium (Cr), 3 against benzoyl peroxide, 1 against gentamycin, 1 against copper and 1 against palladium. In 2 patients the patch test remained negative [58, 65]. LTT showed one hypersensitivity against Ni and Co [16], one against Cr [49], and one LTT remained negative [62].

Out of eight prospective studies, five included patch testing [2, 25, 40, 69]. One study used LTT [47], one study used a combination of patch test and LTT [22], two studies used neither of these tests [8, 10].

In nine of 16 retrospective studies, patch testing was used [17, 19, 33, 35, 45, 51, 52, 54, 61]. In one study, diagnostic procedures also included LTT, ELISA, and confocal microscopy [33].

All 4 review articles refer to patch testing, LTT, “Migration Inhibition Factor” (MIF), and evaluation of cytokines concentration with ELISA as possible diagnostic tests [4, 15, 42, 43]. Reviews outlined the importance of patient reported allergies and history (family history, exposure, occupation, and self-reported allergies) as a first diagnostic step.

(2) In all case reports, the main causes of “painful TKA” were excluded (malpositioning, infection, patellofemoral pain, etc.). In 17 case reports based on diagnosis by exclusion, revisions were performed in 9 instances [1, 9, 16, 18, 24, 49, 58, 62, 65] including 16 cases. In all 16 cases, clear improvements (pain, range of motion) were reported after revision and all systemic symptoms including contact dermatitis, hair loss, etc. disappeared. In all cases, an exclusion of infection was made using intraoperative tissue samples and only 5 patients out of 16 showed periprosthetic tissue changes (mononuclear infiltrate composed of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and macrophages), which were consistent with metal sensitivity [1, 9, 58].

No prospective study analyzed periprosthetic tissue samples to confirm the diagnosis of allergy after TKA. A conversion from preoperative positive patch test or LTT test (37/259; 14.3%) to postoperative positive patch or LTT test (40/172; 23.3%) was assumed as a sign of hypersensitivity to metal components or bone cement.

In 17 retrospective studies, two series reported on revisions for implant allergies [35, 61]. Thomas et al. [61] analyzed periprosthetic tissue in TKA revisions for suspected metal allergy. Four out of 25 patients showed type I changes according to the classification by Krenn et al. [36] (might be compatible to hypersensitive reaction).

(3) Mitchelson et al. [43] and Carulli et al. [15] reported different algorithms in their review articles. Innocenti et al. [33] developed a diagnostic algorithm.

(4) Three prospective studies [8, 10, 40] and two retrospective studies [32, 48] presented alternative materials and treatment options or compared metallic components to hypoallergenic implants. Bergschmidt et al. [8] compared ceramic femoral components (n = 35) with CoCr and CoCrMb (cobalt-chromium-molybdenum) femoral components (n = 35), Lutzner et al. [40] analyzed 60 uncoated Co-Cr-Mb-Ni TKAs and 60 coated (7-layer coating system with a final zirconium nitride (ZrN) layer) TKAs. Pre- and postoperatively patch tests were performed. Pellengahr et al. [48] reported about 35 titanium (Ti-6Al-4 V) TKAs in patch test positive patients in comparison to 45 CrCoNi-alloy TKAs. All three studies showed no significant differences in outcomes (ROM, Knee Society Score, HSS score, metal ion concentration, and WOMAC, SF-36).

Hofer et al. [32] showed a minimum 5-year follow-up of an oxidized zirconium femoral component in 109 TKAs. The authors reported similar survival rates compared to standard TKAs. Bergschmidt et al. [10] reported about 2-year follow-up results with ceramic femoral components in TKA in a prospective multi-center study (n = 110).

Discussion

This review of the current literature was performed with the aim of developing a rational approach to patients that present with self-reported allergies prior to surgery or that require a work-up for undefined pain and swelling after TKA.

The “National Joint Replacement Registry of Australia” [3] notes “metal related pathology” in 1.8% and “undefined pain” in 9.2% as reasons for revision in TKA, which suggests a revision rate of 0.06–0.32% secondary to metal or cement allergies after 10 years. While it is likely that allergies to metal or cement can trigger clinical symptoms and might ultimately lead to revision, allergies have not been associated with implant loosening [23]. Although a positive patch test shows a strong correlation, no causal relationship has been established between dermal reactions and implants failure [62]. Thus, it is not surprising that periprosthetic tissue changes consistent with metal sensitivity were demonstrated in only 31.25% (5/16) of these patients [1, 9, 58].

Clinical Presentation and Symptoms

The initial clinical symptoms may include pain at rest, joint effusions, and decreased range of motion [9, 49, 65]. Skin changes like dermatitis, rash, or hyperthermia are more specific for an allergy but are less common initial symptoms [27, 29, 55]. Decreasing range of motion is a quite common initial sign. The time-range of first symptoms is variable: Bergschmidt et al. [9] report first symptoms (effusion, decreased ROM, and pain) after 4 weeks, Edwards et al. [18] after 6 weeks (generalized knee pain, effusion, and skin rash), and Anand et al. [1] report swelling as a first symptom after 8 weeks. On the other hand, Gao et al. [24] indicate the first symptoms (rash and dermatitis only, no pain, and no decreased ROM) after 6 months. Thakur et al. [58] report persisting pain, swelling, and stiffness as late as 2 years after surgery (in a cohort of 5 patients). Systemic symptoms can also occur; Post et al. [49] describe extensive hair loss and generalized dermatitis.

Diagnostic Tests

Patient History

Self-reported allergies are an important first step in the diagnosis and evaluation of implant allergies. Bloemke et al. [11] showed a prevalence of self-reported cutaneous metal allergies or hypersensitivity in 14% of patients undergoing TKA. A significant gender difference occurred (22% (19/86) female and 2% (1/53) male patients). Two studies [26, 41] showed poor outcomes of TKA in patients with self-reported allergies. It is well known that patients’ mental health is associated with poor outcomes after TKA. Patients reporting allergies are more likely to suffer from anxiety and depression, and these are associated with poor outcomes after TKA [24]. Many self-reported allergies are not confirmed by patch tests [24], and even if an allergy is confirmed a clear association between presence of an allergy and clinical symptoms cannot always be made. Schuh et al. evaluated 300 patients with a TKA and identified 20 patients (6.7%) with an allergy to metal or cement. Only one of these patients had clinical symptoms [54].

Since there is no clear association between self-reported allergies, or skin reactions and a positive patch test (skin) or periprosthetic hypersensitivity reaction (deep tissue) [37, 53, 60, 61] patients should be carefully educated on pros and cons as well as necessity of hypoallergic implants.

Patch Test

Patch testing is the gold standard for the evaluation of type IV hypersensitivity reactions [53]. Allergic reactions to cement and metal in orthopedic implants display distinct characteristics of delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions [43]. Patch tests are in vivo tests, are widely available and easy to apply and provide results within days [53]. However, since there is a difference in antigen-presenting cells in the skin and in periprosthetic deep tissue it is still not clear if patch testing is the best screening test for allergic reactions in orthopedic patients [53, 61]. Nevertheless, 28 of 31 studies reviewed relied on patch testing making it the gold standard for the evaluation of a possible hypersensitivity to metal or bone cement.

Lymphocyte Transformation Test

Lymphocyte transformation test (LTT) is an in-vitro test, which measures the proliferation of lymphocytes derived from peripheral blood in the presence and absence of a potential allergen [53]. The main disadvantages of LTT are its limited availability, the limited number of allergens that can be tested, and the rapid decay of T cells that requires immediate transportation of the blood samples [53]. The main advantages of LTT are its higher sensitivity compared to patch testing [28]. The LTT also provides quantifiable data and is very reproducible [43]. In a prospective study, Niki et al. [47] tested if LTT is an effective preoperative screening tool prior to TKA. The study was able to identify all patients that developed metal related eczema during follow-up, however, the specificity of the LTT was very low [28]. Because of its price and the logistic challenges with current LTT, the test is limited to the evaluation of patients with a symptomatic TKA and unclear results of patch testing and imaging [28].

Further Diagnostic Methods

Carulli et al. [15] described a blood examination to assess the concentration of specific cytokines as well as the confocal microscopy of metal exposed thymidine activated macrophages. Beecker et al. [7] reported about a subcutaneous implantation of Co and Ti implant samples to detect hypersensitivity reactions. Innocenti et al. [33] described an alternative ELISA method to determine hypersensitivity against metal implants. All described tests have limited available and data on the diagnostic value of these tests are scarce.

Intraoperative Biopsies

Intraoperative biopsies and the histopathological work-up remain the gold standard to confirm implant related hypersensitivity. The histological diagnosis of a metal or cement allergy requires a multidisciplinary approach according to Krenn. Krenn et al. [36, 37] described four types of periprosthetic membranes; they stated that allergic reactions are summed in type I periprosthetic membranes with pronounced lymphocytic infiltration. Particular attention has been devoted to the lymphocytic infiltrate without correlation to the characterization of the macrophagic infiltrate or to the morphological and elemental characteristics of the wear particles [37]. Three different lymphocytic infiltration patterns have been described [68]: (1) diffuse pattern with no aggregates; predominantly lymphocytes, sporadic plasma cells; (2) perivascular aggregates of predominantly T cells; and (3) perivascular aggregates containing T and B cells with formation of germinal centers, associated with the presence of high endothelial cell venules. However, the clinical and prognostic importance of these lymphocytic infiltration patterns has not been clarified and the relationship to hypersensitivity reactions remains unclear [68]. Fibrous membrane formation even in the absence of a loose implant is common [44]. Thomas et al. [61] showed a fibrotic (type IV membrane according to Krenn) in 81% of the patch test positive patients. While some surgeons utilize arthroscopic biopsy to confirm a suspected metal allergy before revision surgery, usually the results of the histology are used to confirm the diagnosis after revision surgery.

Hypoallergenic Materials in TKA

If hypersensitivity against metal implants or bone cement is confirmed, hypoallergic materials should be used for TKA. However, two studies [13, 59] report on patients with a confirmed metal allergy (patch test) who had no reactions and symptoms after several years with an orthopedic implant made of these materials. The treatment options include ceramic femoral components that do not contain any metal [10] or implant coatings. Ceramics (Al2O3 or ZrO2) are biological inactive materials that have been used for over 30 years in total hip arthroplasties and have not shown to trigger hypersensitivity reactions. Bergschmidt et al. [8–10] showed in three studies the value of ceramic femoral components (n = 108) compared to CoCr components and presented a case report of a patient with suspected metal hypersensitivity requiring revision surgery using a ceramic femoral component. Ceramic femoral components are not readily available in the USA and are used mainly in Europe.

An alternative to a ceramic femoral component is the readily available zirconium oxide (Oxinium ®, Smith&Nephew) femoral components in combination with a titanium base plate. Oxinium® femoral components contain less than 0.0035% nickel and display excellent tribologic properties including wear resistance, hardness, and wettability [56]. Hofer et al. [32] followed up 109 patients with Oxinium® femoral components and showed equal clinical outcomes to conventional CoCr components. Innocenti et al. [33] used Oxinium® components in 25 patients with suspected hypersensitivity. No hypersensitivity reaction or complications occurred. Oxinium hip and knee implants also have an excellent track record in the Australian registry [3].

The final treatment options are custom titanium niobium nitride (TiNbN) or titanium nitride (TiN) coatings [4]. The titanium or cobalt-chromium surface of a femoral component can be coated using nitrogen [12, 21], oxygen diffusion hardening [57], diamond-like-carbon surfacing [21], or physical-vapor-deposition with titan(niobium)nitride (Ti(Nb)N) [31]. Lutzner et al. [40] compared 60 coated to 60 uncoated CoCr implants. No increased plasma metal ion concentration was shown in either group. Nevertheless, there are reports of third body wear due to delimitation of the TiN coating [30, 38, 50, 64] in hip arthroplasties. This can result in third body polyethylene wear [64]. There were no reports of adverse effects related to TiN coating of CoCrMo knee implants.

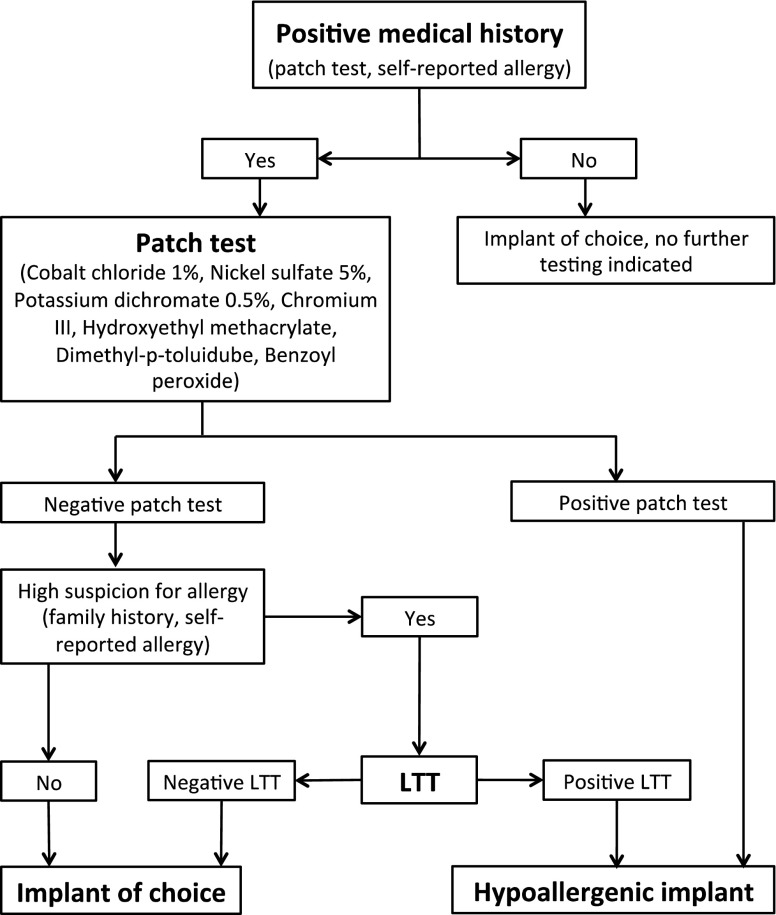

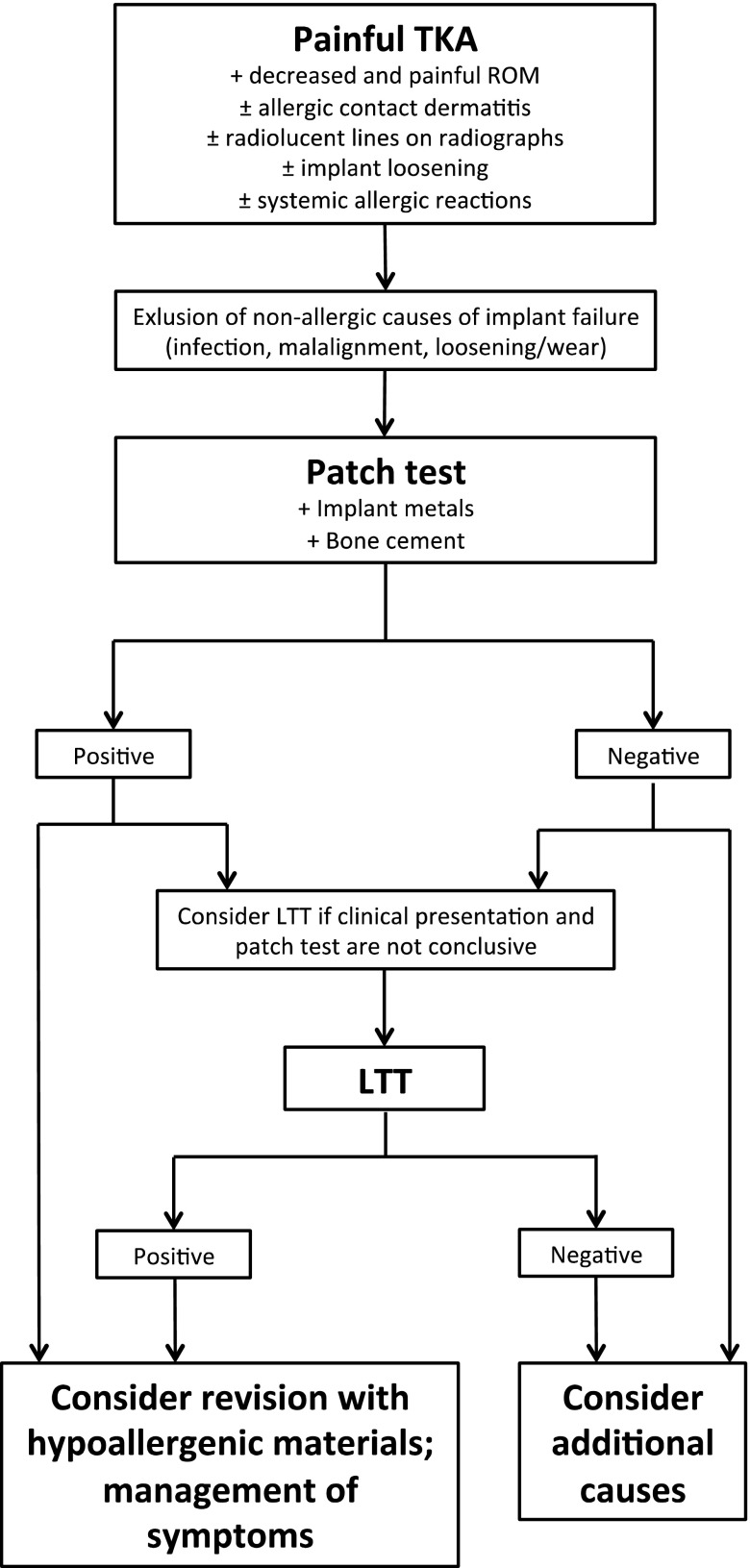

Algorithms

A number of papers have reported algorithms to screen for hypersensitivity against metals or bone cement in patients undergoing TKA [4, 22, 33, 63]. Most algorithms highlight the importance of the patient’s history of metal hypersensitivity/allergic reaction. If the patient’s self reported history is positive, patch testing is usually recommended to confirm the allergy prior to surgery. If the medical history is negative, a further work-up is not recommended and there is no evidence that surgeons need to actively screen for allergies prior to TKA.

Metal hypersensitivity should be assumed in all patients with a positive patch test and alternative implants should be utilized. Further screening methods (LTT, ELISA, and confocal microscopy) are reserved for patients with a symptomatic TKA and a strong clinical suspicion for an allergy in the absence of a positive patch test. Figures 1 and 2 present possible algorithms for the evaluation of patients prior to TKA and for the symptomatic TKA, respectively. Attention should be given to the second point in algorithm two: Since allergies after TKA are very rare, it is essential to perform a thorough work-up to rule out other failure mechanisms (malalignment, loosening or inadequate sizing of the components, and deep implant infection).

Fig. 1.

Algorithm for diagnostic and treatment for patients in need of TKA. (LTT lymphocyte transformation test).

Fig. 2.

Algorithm after TKA with metal implant and clinical symptoms. The decision in favor of revision should only be made after the overall clinical presentation, patch test, and comorbidities are taken into consideration.

Routine allergy testing is currently not recommended and patch testing is reserved for patients with a strong medical history of metal sensitivity. More sophisticated tests including LLT are reserved for patients with a negative patch test but a strong clinical suspicion for an implant allergy. Type I membranes on histologic analysis have been associated with metal hypersensitivity following TKA. Zirconium oxide implants are a readily available treatment option for patients with suspected metal allergy requiring primary or revision TKA. Alternatives include ceramic femoral components or custom coated implants.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

(PDF 1224 kb)

(PDF 1224 kb)

(PDF 1224 kb)

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

Martin Faschingbauer, MD reports other from Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, during the conduct of the study. Lisa Renner, MD has declared that she has no conflict of interest. Friedrich Boettner, MD reports personal fees from Smith & Nephew, during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Ortho Development, outside the work.

Human/Animal Rights

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by the any of the authors.

Informed Consent

N/A

Required Author Forms

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the online version of this article.

Footnotes

Work was performed at Hospital for Special Surgery.

References

- 1.Anand A, McGlynn F, Jiranek W. Metal hypersensitivity: can it mimic infection? The Journal of Arthroplasty. 2009;24(5):826.e25–8. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atanaskova Mesinkovska N, Tellez A, Molina L, Honari G, Sood A, Barsoum W, et al. The effect of patch testing on surgical practices and outcomes in orthopedic patients with metal implants. Archives of Dermatology. 2012;148(6):687–93. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2011.2561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Australian O. Association, Annual Report 2014. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bader R, Bergschmidt P, Fritsche A, Ansorge S, Thomas P, Mittelmeier W. Alternative materials and solutions in total knee arthroplasty for patients with metal allergy. Der Orthopade. 2008;37(2):136–42. doi: 10.1007/s00132-007-1189-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bader R, Mittelmeier W, Steinhauser E. Failure analysis of total knee replacement. Basics and methodological aspects of the damage analysis. Der Orthopade. 2006;35(9):896. doi: 10.1007/s00132-006-0976-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Basko-Plluska JL, Thyssen JP, Schalock PC. Cutaneous and systemic hypersensitivity reactions to metallic implants. Dermatitis : Contact, Atopic, Occupational, Drug. 2011;22(2):65–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beecker J, Gordon J, Pratt M. An interesting case of joint prosthesis allergy. Dermatitis : Contact, Atopic, Occupational, Drug. 2009;20(2):E4–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bergschmidt P, Bader R, Kluess D, Zietz C, Schwemmer B, Kundt G, et al. Total knee replacement system with a ceramic femoral component versus two traditional metallic designs: a prospective short-term study. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery (Hong Kong) 2013;21(3):294–9. doi: 10.1177/230949901302100306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bergschmidt P, Bader R, Mittelmeier W. Metal hypersensitivity in total knee arthroplasty: revision surgery using a ceramic femoral component - a case report. The Knee. 2012;19(2):144–7. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bergschmidt PB, Bader R, Ganzer D, et al. Ceramic Femoral Components in Total Knee Arthroplasty - Two Year Follow-Up Results of an International Prospective Multi-Centre Study. The Open Orthopaedics Journal. 2012;6:172–8. doi: 10.2174/1874325001206010172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bloemke AD, Clarke HD. Prevalence of Self-Reported Metal Allergy in Patients Undergoing Primary Total Knee Arthroplasty. The Journal of Knee Surgery. 2015; 28(3): 243-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Buchanan RA, Rigney ED, Jr, Williams JM. Wear-accelerated corrosion of Ti-6Al-4V and nitrogen-ion-implanted Ti-6Al-4V: mechanisms and influence of fixed-stress magnitude. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 1987;21(3):367–77. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820210309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carlsson A, Moller H. Implantation of orthopaedic devices in patients with metal allergy. Acta Dermato-Venereologica. 1989;69(1):62–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carlsson AS, Magnusson B, Moller H. Metal sensitivity in patients with metal-to-plastic total hip arthroplasties. Acta Orthopaedica Scandinavica. 1980;51(1):57–62. doi: 10.3109/17453678008990769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carulli C, Villano M, Bucciarelli G, Martini C, Innocenti M. Painful knee arthroplasty: definition and overview. Clinical Cases in Mineral and Bone Metabolism : The Official Journal of The Italian Society of Osteoporosis, Mineral Metabolism, and Skeletal Diseases. 2011;8(2):23–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dietrich KA, Mazoochian F, Summer B, Reinert M, Ruzicka T, Thomas P. Intolerance reactions to knee arthroplasty in patients with nickel/cobalt allergy and disappearance of symptoms after revision surgery with titanium-based endoprostheses. Journal der Deutschen Dermatologischen Gesellschaft = Journal of the German Society of Dermatology : JDDG. 2009;7(5):410–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2008.06987.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eben R, Dietrich KA, Nerz C, Schneider S, Schuh A, Banke IJ, et al. Contact allergy to metals and bone cement components in patients with intolerance of arthroplasty. Deutsche Medizinische Wochenschrift (1946) 2010;135(28-29):1418–22. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1262426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Edwards SA, Gardiner J. Hypersensitivity to benzoyl peroxide in a cemented total knee arthroplasty: cement allergy. The Journal of Arthroplasty. 2007;22(8):1226–8. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2006.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elves MW, Wilson JN, Scales JT, Kemp HB. Incidence of metal sensitivity in patients with total joint replacements. British Medical Journal. 1975;4(5993):376–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.4.5993.376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Evans EM, Freeman MA, Miller AJ, Vernon-Roberts B. Metal sensitivity as a cause of bone necrosis and loosening of the prosthesis in total joint replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1974;56-b(4):626–42. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.56B4.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fink U. Safety aspects in the coating of titanium slide components. Der Orthopade. 1997;26(2):160–5. doi: 10.1007/s001320050082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frigerio E, Pigatto PD, Guzzi G, Altomare G. Metal sensitivity in patients with orthopaedic implants: a prospective study. Contact Dermatitis. 2011;64(5):273–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.2011.01886.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gallo J, Goodman SB, Konttinen YT, Wimmer MA, Holinka M. Osteolysis around total knee arthroplasty: a review of pathogenetic mechanisms. Acta Biomaterialia. 2013;9(9):8046–58. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2013.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gao X, He RX, Yan SG, Wu LD. Dermatitis associated with chromium following total knee arthroplasty. The Journal of Arthroplasty. 2011;26(4):665.e13–6. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Granchi D, Cenni E, Tigani D, Trisolino G, Baldini N, Giunti A. Sensitivity to implant materials in patients with total knee arthroplasties. Biomaterials. 2008;29(10):1494–500. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Graves CM, Otero JE, Gao Y, Goetz DD, Willenborg MD, Callaghan JJ. Patient reported allergies are a risk factor for poor outcomes in total hip and knee arthroplasty. The Journal of Arthroplasty. 2014;29(9 Suppl):147–9. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2014.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haeberle M, Wittner B. Is gentamicin-loaded bone cement a risk for developing systemic allergic dermatitis? Contact Dermatitis. 2009;60(3):176–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.2008.01482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hallab NJ, Caicedo M, Finnegan A, Jacobs JJ. Th1 type lymphocyte reactivity to metals in patients with total hip arthroplasty. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research. 2008;3:6. doi: 10.1186/1749-799X-3-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Handa S, Dogra S, Prasad R. Metal sensitivity in a patient with a total knee replacement. Contact Dermatitis. 2003;49(5):259–60. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-1873.2003.0225b.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harman MK, Banks SA, Hodge WA. Wear Analysis of a Retrieved Hip Implant With Titanium Nitride Coating. The Journal of Arthroplasty. 1997;12(8):938–45. doi: 10.1016/S0883-5403(97)90164-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hendry JA, Pilliar RM. The fretting corrosion resistance of PVD surface-modified orthopedic implant alloys. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 2001;58(2):156–66. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(2001)58:2<156::AID-JBM1002>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hofer JK, Ezzet KA. A minimum 5-year follow-up of an oxidized zirconium femoral prosthesis used for total knee arthroplasty. The Knee. 2014;21(1):168–71. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2013.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Innocenti M, Carulli C, Matassi F, Carossino AM, Brandi ML, Civinini R. Total knee arthroplasty in patients with hypersensitivity to metals. International Orthopaedics. 2014;38(2):329–33. doi: 10.1007/s00264-013-2229-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaplan K, Della Valle CJ, Haines K, Zuckerman JD. Preoperative identification of a bone-cement allergy in a patient undergoing total knee arthroplasty. The Journal of Arthroplasty. 2002;17(6):788–91. doi: 10.1054/arth.2002.33571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krecisz B, Kiec-Swierczynska M, Bakowicz-Mitura K. Allergy to metals as a cause of orthopedic implant failure. International Journal of Occupational Medicine and Environmental Health. 2006;19(3):178–80. doi: 10.2478/v10001-006-0025-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krenn V, Morawietz L, Kienapfel H, Ascherl R, Matziolis G, Hassenpflug J, et al. Revised consensus classification. Histopathological classification of diseases associated with joint endoprostheses. Zeitschrift fur Rheumatologie. 2013;72(4):383–92. doi: 10.1007/s00393-012-1099-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krenn V, Morawietz L, Perino G, Kienapfel H, Ascherl R, Hassenpflug GJ, et al. Revised histopathological consensus classification of joint implant related pathology. Pathology, Research and Practice. 2014;210(12):779–86. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2014.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lappalainen R, Santavirta SS. Potential of Coatings in Total Hip Replacement. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2005;430:72–9. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000150000.75660.ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lieberman P, Fonacier L. Systemic contact dermatitis possibly related to metal implants. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology In Practice. 2014;2(4):487. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2014.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lutzner J, Hartmann A, Dinnebier G, Spornraft-Ragaller P, Hamann C, Kirschner S. Metal hypersensitivity and metal ion levels in patients with coated or uncoated total knee arthroplasty: a randomised controlled study. International Orthopaedics. 2013;37(10):1925–31. doi: 10.1007/s00264-013-2010-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McLawhorn AS, Bjerke-Kroll BT, Blevins JL, Sculco PK, Lee YY, Jerabek SA. Patient-Reported Allergies Are Associated With Poorer Patient Satisfaction and Outcomes After Lower Extremity Arthroplasty: A Retrospective Cohort Study. The Journal of Arthroplasty. 2015; 30(7): 1132-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Meyer H, Kruger A, Roessner A, Lohmann CH. Allergic reactions as differential diagnosis for periprosthetic infection. Der Orthopade. 2012;41(1):26–31. doi: 10.1007/s00132-011-1838-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mitchelson AJ, Wilson CJ. Biomaterial Hypersensitivity: Is It Real? Supportive Evidence and Approach Considerations for Metal Allergic Patients following Total Knee Arthroplasty. BioMed Research International. 2015; 2015: 137287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Morawietz L, Krenn V. The spectrum of histomorphological findings related to joint endoprosthetics. Der Pathologe. 2014;35 Suppl 2:218–24. doi: 10.1007/s00292-014-1976-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Munch HJ, Jacobsen SS, Olesen JT, et al. The association between metal allergy, total knee arthroplasty, and revision: study based on the Danish Knee Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthopaedica. 2015; 86(3): 378-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Nasser S. Orthopedic metal immune hypersensitivity. Orthopedics. 2007;30(8 Suppl):89–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Niki Y, Matsumoto H, Otani T, Yatabe T, Kondo M, Yoshimine F, et al. Screening for symptomatic metal sensitivity: a prospective study of 92 patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty. Biomaterials. 2005;26(9):1019–26. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pellengahr C, Mayer W, Maier M, Muller PE, Schulz C, Durr HR, et al. Resurfacing knee arthroplasty in patients with allergic sensitivity to metals. Archives of Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery. 2003;123(4):139–43. doi: 10.1007/s00402-002-0429-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Post ZD, Orozco FR, Ong AC. Metal sensitivity after TKA presenting with systemic dermatitis and hair loss. Orthopedics. 2013;36(4):e525–8. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20130327-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Raimondi MT, Pietrabissa R. The in-vivo wear performance of prosthetic femoral heads with titanium nitride coating. Biomaterials. 2000;21(9):907–13. doi: 10.1016/S0142-9612(99)00246-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rau C, Thomas P, Thomsen M. Metal sensitivity in patients with joint replacement arthroplasties before and after surgery. Der Orthopade. 2008;37(2):102–10. doi: 10.1007/s00132-007-1186-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Reed KB, Davis MD, Nakamura K, Hanson L, Richardson DM. Retrospective evaluation of patch testing before or after metal device implantation. Archives of Dermatology. 2008;144(8):999–1007. doi: 10.1001/archderm.144.8.999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schalock PC, Menne T, Johansen JD, Taylor JS, Maibach HI, Liden C, et al. Hypersensitivity reactions to metallic implants - diagnostic algorithm and suggested patch test series for clinical use. Contact Dermatitis. 2012;66(1):4–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.2011.01971.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schuh A, Lill C, Honle W, Effenberger H. Prevalence of allergic reactions to implant materials in total hip and knee arthroplasty. Zentralblatt fur Chirurgie. 2008;133(3):292–6. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1076830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schuh A, Thomas P, Reinhold R, Holzwarth U, Zeiler G, Mahler V. Allergic reaction to components of bone cement after total knee arthroplasty. Zentralblatt fur Chirurgie. 2006;131(5):429–31. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-949533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Smith&Nephew . www.smith-nephew.com. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Streicher RM, Weber H, Schon R, Semlitsch M. New surface modification for Ti-6Al-7Nb alloy: oxygen diffusion hardening (ODH) Biomaterials. 1991;12(2):125–9. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(91)90190-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thakur RR, Ast MP, McGraw M, Bostrom MP, Rodriguez JA, Parks ML. Severe persistent synovitis after cobalt-chromium total knee arthroplasty requiring revision. Orthopedics. 2013;36(4):e520–4. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20130327-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thienpont E, Berger Y. No allergic reaction after TKA in a chrome-cobalt-nickel-sensitive patient: case report and review of the literature. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy : Official Journal of The ESSKA. 2013;21(3):636–40. doi: 10.1007/s00167-012-2000-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Thomas P, Summer B, Krenn V, Thomsen M. Allergy diagnostics in suspected metal implant intolerance. Der Orthopade. 2013;42(8):602–6. doi: 10.1007/s00132-012-2033-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Thomas P, von der Helm C, Schopf C, et al. Patients with Intolerance Reactions to TKA: Combined Assessment of Allergy Diagnostics, Periprosthetic Histology, and Peri-implant Cytokine Expression Pattern. BioMed Research International. 2014; 2014: 910156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 62.Thomsen M, Rozak M, Thomas P. Pain in a chromium-allergic patient with total knee arthroplasty: disappearance of symptoms after revision with a special surface-coated TKA--a case report. Acta Orthopaedica. 2011;82(3):386–8. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2011.579521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Thomsen M, Rozak M, Thomas P. Use of allergy implants in Germany: results of a survey. Der Orthopade. 2013;42(8):597–601. doi: 10.1007/s00132-012-2032-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.van Hove RP, Sierevelt IN, van Royen BJ, Nolte PA. Titanium-Nitride Coating of Orthopaedic Implants: A Review of the Literature. BioMed Research International. 2015; 2015: 485975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 65.Van Opstal N, Verheyden F. Revision of a tibial baseplate using a customized oxinium component in a case of suspected metal allergy. A case report. Acta Orthopaedica Belgica. 2011;77(5):691–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Verma SB, Mody B, Gawkrodger DJ. Dermatitis on the knee following knee replacement: a minority of cases show contact allergy to chromate, cobalt or nickel but a causal association is unproven. Contact Dermatitis. 2006;54(4):228–9. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-1873.2006.0775o.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Waterman AH, Schrik JJ. Allergy in hip arthroplasty. Contact Dermatitis. 1985;13(5):294–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1985.tb02581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Witzleb WC, Hanisch U, Kolar N, Krummenauer F, Guenther KP. Neo-capsule tissue reactions in metal-on-metal hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthopaedica. 2007;78(2):211–20. doi: 10.1080/17453670710013708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zeng Y, Feng W, Li J, Lu L, Ma C, Zeng J, et al. A prospective study concerning the relationship between metal allergy and post-operative pain following total hip and knee arthroplasty. International Orthopaedics. 2014;38(11):2231–6. doi: 10.1007/s00264-014-2367-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 1224 kb)

(PDF 1224 kb)

(PDF 1224 kb)