Abstract

Background:

Anti-programmed cell death 1 antibody nivolumab is a promising agent for various cancers. Immune-related adverse events are recognized; however, bi-cytopenia with nivolumab has not been reported.

Case presentation:

A 73-year-old man was diagnosed with advanced primary malignant melanoma of the esophagus with liver, lung, and lymph node metastases. Previous therapies including dacarbazine and radiation of 39 Gy to the esophageal region were performed, but the liver metastases deteriorated. The patient was then administered nivolumab (2 mg/kg, every 3 weeks). After 3 cycles, the esophageal tumor and lymph nodes showed marked reductions in size, the lung metastases disappeared, and the liver metastases shrank partially. The treatment continued with 7 cycles for 4 months. However, severe anemia and thrombocytopenia appeared in the 6th cycle, and intermittent blood transfusions were required. The patient received high-dose intravenous methylprednisolone therapy for bi-cytopenia, but it was ineffective. Seven months after the initiation of nivolumab, the patient died of tumor. Although the mechanisms of bi-cytopenia were unclear, it could have been induced by nivolumab.

Conclusion:

The present case shows a rare but serious life-threatening bi-cytopenia possibly associated with nivolumab and suggests the importance of awareness of hematological adverse events during nivolumab therapy.

Keywords: anemia, melanoma, nivolumab, thrombocytopenia

1. Introduction

Primary malignant melanoma of the esophagus (PMME) is a rare but highly aggressive neoplasm, accounting for <0.2% of all primary esophageal neoplasms.[1] Although dacarbazine monotherapy and combination therapy with interferon-γ, interferon-α, and interleukin-2 have been used for advanced malignant melanoma, the 1-year survival rate was only 36% to 48%.[2] In 2011, the cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) antibody ipilimumab was confirmed effective for advanced malignant melanoma and approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Then, the anti-programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) antibody nivolumab was first approved for advanced malignant melanoma in Japan in July 2014, and the 1-year survival rate improved to 72.9%.[3] Nivolumab is a human IgG4 anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody targeting the immune checkpoint molecule PD-1, by which functionally exhausted T cells in the tumor microenvironment regain anti-tumor cytotoxicity.[4] According to clinical trials of anti-PD-1 antibodies, adverse events, such as interstitial pneumonia, endocrine system dysfunction, and liver damage that were different from those of cytotoxic chemotherapies, were reported. However, the incidence of myelosuppression induced by anti-PD-1 antibodies has not been reported.[3,5,6]

2. Case report

A 73-year-old man who was treated with hypertension and hyperuricemia visited a primary care physician with a complaint of progressive dysphagia in February 2014. Esophagoscopy showed an amelanotic ulcerating tumor at the thoracic esophagus with its longest axis being approximately 5 cm, and the patient was then referred to our hospital. Carcinosarcoma was most suspected by initial biopsy specimen because of atypical short spindle to polygonal cells, which was focally positive for S-100 but negative for anti-cytokeratins (AE1/AE3, CAM5.2, CK903, CK7, CK20) by immunohistochemically analysis. Although, the re-biopsy specimen showed proliferation of atypical oval to rounded cells that were positive for S-100, human melanoma black (HMB)-45, and Melan-A, but negative for anti-cytokeratins and p63 (Fig. 1). Since the re-biopsy specimen also included atypical short spindle to polygonal cells, which resembled to the initial biopsy, the patient was finally diagnosed with malignant melanoma with sarcomatoid component. As no malignant lesions without esophagus and the regional lymph nodes were seen by the imaging examinations including computed tomography (CT) and positron emission tomography (PET), the esophagus tumor was diagnosed as primary. Moreover, a cervical lymph node metastasis invaded the adjacent artery, and the patient was diagnosed as having unresectable PMME. According to the initial suspected diagnosis of carcinosarcoma, chemotherapy consisting of docetaxel, cisplatin, and 5-fluorouracil was performed for 3 cycles, but the esophageal tumor enlarged, and new liver metastases appeared. Then, dacarbazine monotherapy and palliative radiotherapy of 39 Gy to the obstructive esophageal tumor were subsequently performed based on the histological diagnosis of the re-biopsy specimen. After the radiotherapy and 1 cycle of dacarbazine, new liver and lung metastases appeared, with deterioration of general status. The patient was referred to the department of hematology and oncology for further treatment in September 2014. His Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status was 2, and enteral nutrition was required because of difficulty swallowing. Although the patient had moderate macrocytic anemia, mild thrombocytopenia, and mild elevation of hepatobiliary enzymes, no other organ insufficiency was suggested in the laboratory data (red blood cell count 247 × 104 cells/μL, hemoglobin (Hb) 8.8 g/dL, mean corpuscular volume 112 fL, mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration 31.8 g/dL, platelet count 11.9 × 104 cells/μL, aspartate transaminase 54 U/L, alanine transaminase 17 U/L, and total bilirubin 0.4 mg/dL). CT showed a mass occupying the entire circumference of the esophagus, which was shown to be an amelanotic obstructive tumor on esophagoscopy (Fig. 2A). CT also showed multiple liver metastases of various sizes and small metastases in both lungs (Fig. 2B).

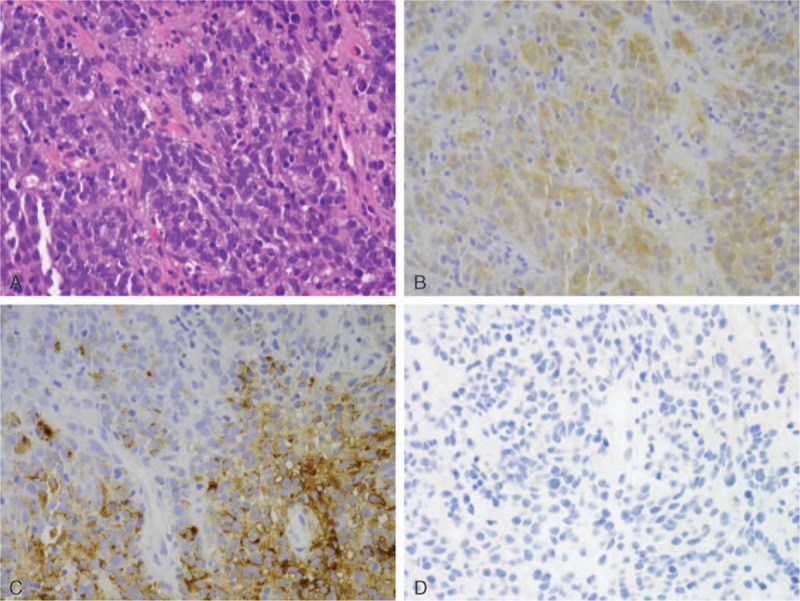

Figure 1.

Pathohistological examination of the biopsy sample. (A) Proliferation of atypical oval to rounded cells that have hyperchromatic nuclei. Mitotic figures are frequently seen. Hematoxylin and eosin staining; magnification, ×400. (B, C, D) Immunohistochemically, the atypical tumors cells were positive for S-100 (B), HMB-45 (C) and AE1/AE3 (D). S-100, HMB-45, and AE1/AE3 staining; magnification, ×400.

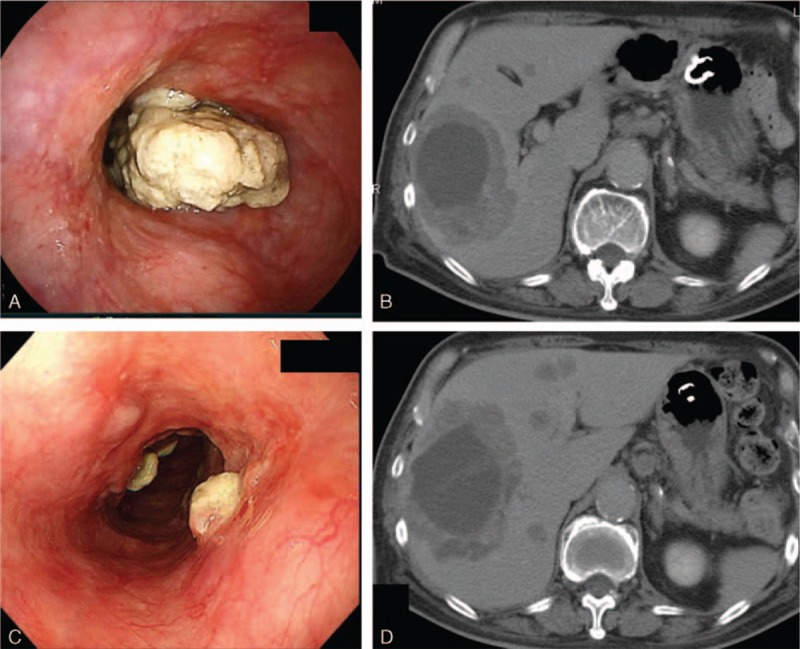

Figure 2.

(A) Esophagoscopy shows an amelanotic tumor that occupies the entire circumference of the esophageal tract in the middle intrathoracic esophagus. (B) Enhanced CT images before nivolumab therapy show multiple liver metastases of various sizes. (C) Following the 3rd cycle of nivolumab therapy, the esophageal tumor shrunk dramatically. (D) Following the 3rd cycle of nivolumab therapy, the liver metastases shrunk partially.

As the patient had a nonmutated BRAF gene, the patient was started on intravenous administration of nivolumab (2 mg/kg, every 3 weeks) from September 2014. After 3 cycles, the esophageal tumor shrank dramatically to approximately 2 cm, the dysphagia was ameliorated, and the patient could eat normally (Fig. 2C). After 7 cycles, the esophageal tumor had remained stable, and the patient's performance status had improved from 2 to 1 after administration of nivolumab. The largest liver metastasis (diameter, 10 cm) in the right lobe was not remarkably changed in size, whereas other small liver metastases that had a maximum diameter of 1 to 2 cm decreased in size (Fig. 2D). All lung metastases cleared. The clinical response after 3 cycles was stable disease by Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1. However, after 7 cycles, the liver metastases enlarged rapidly, and many new liver metastases occurred. Nivolumab therapy was then stopped because of disease progression.

The anemia had gradually worsened and required intermittent red blood cell transfusions in the 6th cycle; the Hb was 7.3 g/dL, grade 4 by Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 4.0. Persistent bleeding in the metastatic huge liver tumor with internal necrosis was suspected, and palliative radiotherapy of 45 Gy to the liver tumors was performed from February 2015. During the radiotherapy, the anemia progressed, and it was complicated by severe thrombocytopenia and required platelet transfusions; the platelet count was 2.3 × 104 cells/μL, grade 4 by CTCAE. On close investigation, there were no findings of gastrointestinal bleeding on endoscopy, hemolytic anemia (haptoglobin 75 mg/dL, direct Coomb test negative), iron deficiency anemia (serum-iron 74 μg/dL, ferritin 1284 ng/mL), vitamin deficiency anemia (vitamin B12 329 pg/mL, folic acid 5.6 ng/mL), autoimmune disease (anti-nuclear antibody plus or minus, double-strand DNA negative), disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP), or infection. Anti-platelet antibody was negative, and platelet-associated IgG (PA-IgG) was 28.4 ng/107 cells, which was within the normal range. On bone marrow aspiration, the bone marrow was normal-plastic with no obvious morphological abnormalities, phagocytosis, or invasion of melanoma cells; the nuclear cell count was 9.3 × 104 cells/μl, and the myeloid:erythroid (M:E) ratio was 1.70. G-banding of bone marrow was normal (46XY). Megakaryocytes in the bone marrow were 44 cells/μl, which was not increased. Megakaryocytes were mostly immature, and platelets infrequently adhered to them. In the flow-cytometry analysis of bone marrow mononuclear cells, the ratio of T lymphocytes, natural killer cells plasma cells, and B lymphocytes were 89%, 6.4%, 2.3%, and 1.1% of all lymphocytes. Reticulocytes in peripheral blood cells were 12% (normal range 6%–20%). Although the progenitors of red blood cells and platelets in the bone marrow were maintained, there were no findings of a reactive increase of reticulocytes in peripheral blood or hyperplastic findings of bone marrow in response to the severe bi-cytopenia. Although the etiology of the severe anemia and thrombocytopenia was unclear, the involvement of nivolumab could not be ruled out.

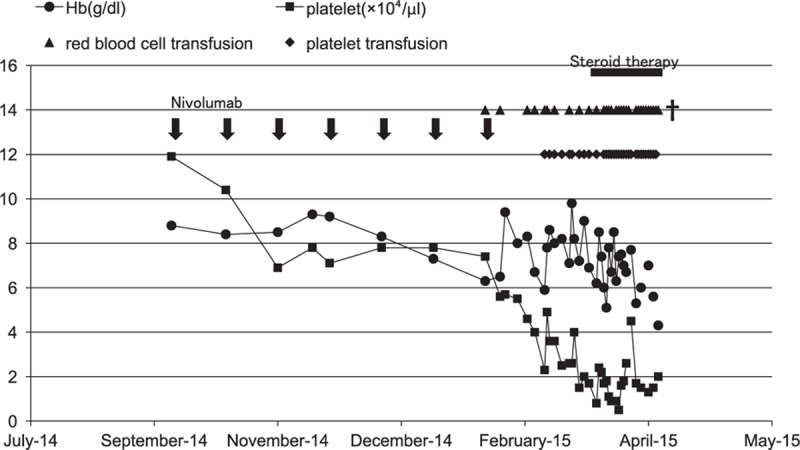

In March 2015, steroid-pulse therapy was started with the patient's consent, with intravenous methylprednisolone administration 500 mg/day, days 1 to 3, and intravenous prednisolone 5 mg/kg (30 mg/day) (Fig. 3). A large amount of melena occurred on the 4th day of steroid administration. Capsule endoscopy revealed multiple hemorrhagic protruded tumors in the small intestine, which were considered to be metastases of malignant melanoma. The steroid therapy and red blood cell and platelet transfusions continued, but bi-cytopenia did not recover. The melena continued, and the patient died in April 2015.

Figure 3.

The changes in hemoglobin and platelet counts after nivolumab therapy. Arrows show the administration of nivolumab (2 mg/kg). Closed circles show the hemoglobin level (g/dL). Closed squares show the platelet count (×104 cells/μL). Closed triangles show red blood cell transfusions, with 2 U given each time. Closed diamonds show platelet transfusions, with 10 U given each time. The black column shows steroid therapy.

The written informed consent for the case report was obtained from this patient.

3. Discussion

The incidence of malignant melanoma has been increasing over the past decades, and approximately 132,000 people develop it each year worldwide.[7] Although almost all cases diagnosed as malignant melanoma arise from the skin, it is reported that only 1% of melanomas arise from mucosa (head and neck, eyes, and genitourinary and alimentary tracts).[8] Although mucosal melanomas generally carry a worse prognosis than those arising from cutaneous sites, no intrinsic risk factors and specific treatment options have been established, and there is no evidence of a difference in sensitivity between skin and mucosal melanomas to nivolumab therapy.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors, anti-CTLA-4 antibody and anti-PD-1 antibodies, have shown good results for the treatment of advanced malignant melanoma.[3,5,6] Nivolumab is a human IgG4 anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody targeting PD-1. In the present case, although the primary tumor that occupied the esophagus and lung metastases shrank markedly after 3 cycles and remained stable, liver metastases shrank only in part, and other metastases showed no changes in size after 3 cycles and then became rapidly bigger after 7 cycles. Progression-free survival with nivolumab therapy was relatively short in the present case, but a moderate effect was seen for PMME.

According to clinical trials of anti-PD-1 antibodies, a variety of immune-related adverse events occurred in the lung, liver, and endocrine organs. However, myelosuppression was rare.[3,5,6] To the best of our knowledge, there has been no report of bi-cytopenia with nivolumab therapy. Kanameishi et al[9] reported a metastatic melanoma patient who developed thrombocytopenia after nivolumab therapy. They diagnosed idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) induced by nivolumab because the antiplatelet antibody was positive, and there was no evidence of infection or autoimmune disorders. However, since there was no evidence of anti-platelet antibody or PA-IgG in the present case, other mechanisms for the myelosuppression are suggested. Bi-cytopenia is often associated with aplastic anemia, myelodysplastic syndrome, DIC, and TTP, but there was nothing to suggest them in the present case. Dysfunction of maturation or proliferation of hematopoietic stem cells and progenitor cells was considered, but the detailed mechanism is unknown. Additionally, possible influences by compromised immune system and deficient nutrition to the disease may be considerable.

With another immune checkpoint inhibitor, ipilimumab, there have been only 6 case reports of myelosuppression.[10–13] One of these cases developed thrombocytopenia and was diagnosed with ITP.[10] Two cases developed severe anemia and were diagnosed with aplastic anemia and hemolytic anemia, respectively.[11,12] The patients received high- or low-dose steroid therapy and 4 of the 6 cases responded to steroid therapy, but 2 cases were resistant and then received intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG). As a short prognosis was expected because of the continuous hemorrhage from intestinal metastases in the present case, intermittent red blood cell and platelet transfusions but not IVIG were performed as palliative care.

4. Conclusion

Severe bi-cytopenia possibly caused by nivolumab therapy was observed in the present case. Clinicians should be aware of the possibility of less frequent types of immune-related adverse events with nivolumab therapy. Further examinations of the mechanisms of the adverse events are needed.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CT = computed tomography, CTCAE = Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, CTLA-4 = cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4, DIC = disseminated intravascular coagulation, ECOG = Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, FDA = Food and Drug Administration, Hb = hemoglobin, HMB = human melanoma black, ITP = idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, IVIG = intravenous immunoglobulin, PA-IgG = platelet-associated IgG, PD-1 = anti-programmed cell death 1, PET = positron emission tomography, PMME = primary malignant melanoma of the esophagus, RECIST = Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors, TTP = thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura.

KA had a research grant from Ono Pharm.

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Yano M, Shiozaki H, Murata A, et al. Primary malignant melanoma of the esophagus associated with adenocarcinoma of the lung. Surg Today 1998; 28:405–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agarwala SS. Current systemic therapy for metastatic melanoma. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 2009; 9:587–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robert C, Long GV, Brady B, et al. Nivolumab in Previously Untreated Melanoma without BRAF Mutation. N Engl J Med 2015; 372:320–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McDermott DF, Atkins MB. PD-1 as a potential target in cancer therapy. Cancer Med 2013; 2:662–673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hodi FS, O’Day SJ, McDermott DF, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med 2010; 363:711–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brahmer JR, Tykodi SS, Chow LQ, et al. Safety and activity of anti-PD-L1 antibody in patients with advanced cancer. N Engl J Med 2012; 366:2455–2465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.WorldHealth Organization. Skin cancers. (Accessed May 12, 2015, Available at http://www.who.int/uv/faq/skincancer/en/index1.html.) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang AE, Karnell LH, Mench HR. The National Cancer Data Base report on cutaneous and noncutaneous melanoma: a summary of 84,836 cases from the past decade. The American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer and the American Cancer Society. Cancer 1998; 83:1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kanameishi S, Otsuka A, Nonomura Y, et al. Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura induced by nivolumab in a metastatic melanoma patient with elevated PD-1 expression on B cells. Ann Oncol 2016; 27:546–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kopecký J, Trojanová P, Kubeček O, et al. Treatment possibilities of ipilimumab-induced thrombocytopenia–case study and literature review. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2015; 45:381–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simeone E, Grimaldi AM, Esposito A, et al. Serious haematological toxicity during and after ipilimumab treatment: a case series. J Med Case Rep 2014; 8:240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gordon IO, Wade T, Chin K, et al. Immune-mediated red cell aplasia after anti-CTLA-4 immunotherapy for metastatic melanoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2009; 58:1351–1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahmad S, Lewis M, Corrie P, et al. Ipilimumab-induced thrombocytopenia in a patient with metastatic melanoma. J Oncol Pharm Pract 2012; 18:287–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]