Abstract

Background:

Reactive perforating collagenosis (RPC) is a rare form of transepithelial elimination, in which altered collagen is extruded through the epidermis. There are 2 types of RPC, acquired RPC (ARPC) and inherited RPC, while the latter is extremely rare. Here we report on 1 case of ARPC.

Methods:

A 73-year-old female was presented with strongly itchy papules over her back and lower limbs for 3 months. She denied the history of oozing or vesiculation. A cutaneous examination showed diffusely distributed multiple well-defined keratotic papules, 4 to 10 mm in diameter, on the bilateral lower limbs and back as well as a few papules on her chest and forearm. Scratching scars were over the resolved lesions while Koebner phenomenon was negative. The patient had a history of type 2 diabetes for 15 years. Laboratory examinations showed elevated blood glucose level. Skin lesion biopsy showed a well-circumscribed area of necrosis filled with a keratotic plug. Parakeratotic cells and lymphocytic infiltration could be seen in the necrosed area. In dermis, sparse fiber bundles were seen perforating the epidermis. These degenerated fiber bundles were notarized as collagen fiber by elastic fiber stain, suggesting a diagnosis of RPC.

Results:

Then a diagnosis of ARPC was made according to the onset age and the history of diabetes mellitus. She was treated with topical application of corticosteroids twice a day and oral antihistamine once a day along with compound glycyrrhizin tablets 3 times a day. And the blood glucose was controlled in a satisfying range. Two months later, a significant improvement was seen in this patient.

Conclusion:

Since there is no efficient therapy to RPC, moreover, ARPC is considered to be associated with some systemic diseases, the management of the coexisting disease is quite crucial. The patient in this case received a substantial improvement due to the control of blood glucose and application of compound glycyrrhizin tablets.

Keywords: acquired reactive perforating collagenosis, ARPC, reactive perforating collagenosis, RPC

1. Introduction

There are 4 classical forms of transepithelial elimination (TEE) disorders: reactive perforating collagenosis (RPC), elastosis perforans serpiginosa (EPS), perforating folliculitis (PF), and Kyrle disease (KD). These 4 diseases share common features of elimination of altered dermal components through epidermis; also they have some specific differentiating features.[1]

RPC is a rare form of TEE, in which altered collagen is genetically extruded through the epidermis.[2] There are 2 types of RPC, acquired RPC (ARPC) and inherited RPC and it is indicated that ARPC may be associated with several inflammatory or malignant systemic diseases.[3] Here, we reported a case of ARPC accompanied with diabetes mellitus.

2. Consent

This patient signed informed consent for the publication of this case report and the associated images. And this study was approved by the ethics committee of Shanghai Tenth People's Hospital, Tongji University School of Medicine.

3. Case report

A 73-year-old female was presented to our out-patient department with strongly itchy papules over her back and bilateral lower limbs for 3 months without specific causes. The exacerbation of pruritus and lesions was presented through time. There was no history of oozing or vesiculation during the whole course of disease. Cutaneous examination revealed diffusely distributed multiple well-defined keratotic papules on the bilateral lower limbs and back, also a few papules on the chest and forearm. Those keratotic papules, 4 to 10 mm in diameter were adhered by keratotic plugs in the center. Scars caused by scratching could be seen over the resolved lesions (Fig. 1) and Koebner phenomenon was negative. Oral mucosa, vaginal mucosa, and cutaneous appendages were normal. Systemic examination was unremarkable. The patient had a history of type 2 diabetes for 15 years. Laboratory examinations showed elevated blood glucose level. Complete hemogram, hepatic function tests, and renal function tests were within normal ranges.

Figure 1.

Lesions of the patient presented as multiple well-defined keratotic papules on the bilateral lower limbs (A) and back (C) diffusely distributed, also few papules can be seen on the upper limbs (B).

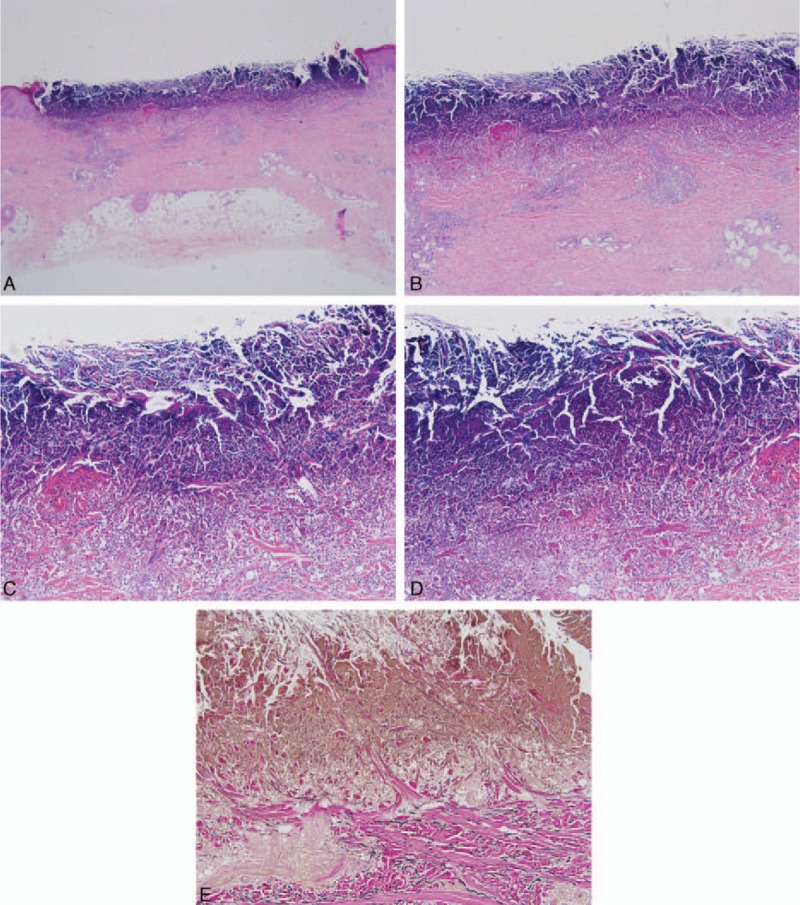

Biopsy showed a well-circumscribed area of necrosis filled with a keratotic plug. In the necrosed area, parakeratotic cells and lymphocytic infiltration could be seen. Sparse fiber bundles in dermis were seen to perforate epidermis. These degenerated fiber bundles were notarized as collagen fiber by elastic fiber stain, suggesting a diagnosis of RPC (Fig. 2). According to the onset age and the accompany disease, diabetes mellitus, we tended to make a diagnosis of ARPC.

Figure 2.

Biopsy examination shows a well-circumscribed area of necrosis, which is filled with a keratotic plug (A) (H&E ×20). In the necrosed area, parakeratotic cells and lymphocytic infiltration can be seen (B) (H&E ×40). Sparse fiber bundles perforate from dermis to epidermis. (C, D) (H&E ×100, H&E ×200). These degenerated fiber bundles were notarized as collagen fiber (color red by elastic fiber stain (E) (elastic stain ×100). H&E = haematoxylin and eosin.

The treatment with topical application of corticosteroids twice a day and oral antihistamine once a day along with compound glycyrrhizin tablets (manufactured by Japanese Minophagen Pharmaceutical Co (Ltd, 3F Shinjuku Mitsui Bldg #2, 3-2-11, Nishi-Shinjuku Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo 160-0023, JAPAN), containing 25 mg glycyrrhizin, 35 mg monoammonium glycyrrhizinate, 25 mg aminoacetic acid, and 25 mg methionine per tablet) 3 times per day and 2 tablets per time resulted in fair improvement over the period of 2 months. Moreover, an expert on endocrinology was invited for a consultation to control the blood glucose.

4. Discussion

RPC is a rare skin disorder characterized by transepidermal elimination of altered collagen through the epidermis.[4] The first case was reported by Mehregan et al[5] in 1967. There are 2 patterns of RPC: inherited RPC is relatively rare and usually seen in children, while acquired RPC (ARPC) can usually be seen in adults,[2] which is sometimes accompanied by systemic diseases. ARPC is also said to be triggered by minor trauma, arthropod bites, scabies infection, and scratching.[6]

Although the pathogenesis of ARPC is unknown, overexpression of transforming growth factor-3 (TGF-β3) has been seen in many ARPC patients. TGF-β, matrix metalloproteinase-1, and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 immunoreactivity were significantly increased in the lesions of ARPC,[7] indicating the crucial function of these factors in regulating epidermal homeostasis, postponing the re-epithelialization and remodeling, and changing extracellular matrix protein metabolism.

Moreover, some authors indicate that the genetic abnormality of the collagen causes the focal damage of RPC and leads to collagen perforation after necrolysis of the overlying epidermis. While some researches support the theory that transepidermal elimination of collagen is simply a reaction to chronic scratching or rubbing in pruritic diseases.[8]

There are 4 classical forms of TEE disorders: RPC, EPS, PF, and KD. These 4 diseases share common features of elimination of altered dermal components through epidermis and the differentiation is made according to the types of epidermal damage and the features of elimination material. The classic lesion and histopathological examination are the major distinguishing characteristics. The classic lesions of RPC are isolated papules, with keratotic plugs in the center, and are usually self-healing in 6 to 8 weeks without any therapy, but often recur. And the histopathological changes of the lesion show hyperplasia, thickening of epidermis, and widening of papillary dermis, with degenerated collagen bundles in the early period. In the later period, cup-shape invagination of epidermis can be seen, which is filled with keratotic plug, intermingled with parakeratotic cells, degenerated collagen fibers and cell fragments. Necrotic basophilic collagen fibers are eliminated to epidermis. The lesions of EPS patients are usually keratosis papules, with desquamation or atrophy in the center. Those asymptomatic or pruriginous plaques grouped in arciform or serpiginous pattern.[9] Lesions of PF patients are isolated papules, with white keratotic plugs in the center, curly can be seen in the keratotic plug. The lesions of KD are papules filled with conical keratotic plugs, which are always found near follicle. Histopathological examination is crucial for differential diagnosis.

We reviewed some cases of ARPC reported in the literature and tried to summarize the clinical characteristics, effective management, as well as prognosis. In general, the skin lesions of the majority were described as multiple round plaques and nodules with central hyperkeratotic plugs, usually distributing on the extremities and back, sometimes face and neck. Pruritus was common but Koebner phenomenon was not mentioned in most of the cases, not as previously reported.[10] Of these patients, the most common associated diseases were diabetes mellitus (DM, type 1, and type 2 were both reported) and complications of DM, including chronic renal failure, cardiopathy, and retinopathy.[11–16] Some autoimmune diseases were regarded to be associated as well, such as systemic lupus erythematous,[17] vasculitis,[18,19] dermatomyositis,[6,20] and Mikulicz disease (an IgG4-related disease).[21] Moreover, some malignancies, including lymphoma, thyroid carcinoma, and breast carcinoma, were also reported as coexisting diseases.[22,23]

Currently, there is no efficient therapy to RPC. Treatment is mainly aimed at controlling the symptom. In the literature, multiple treatments, including topical corticosteroids under occlusion, emollients, keratolytics retinoids, systemic antihistaminics, allopurinol, isotretinoinm, narrow-band ultraviolet B phototherapy, and liquid nitrogen cryotherapy, have been tried, with different degrees of improvements.[24,25]

In the case of our patient, compound glycyrrhizin tablet was one of the treatments. Glycyrrhizin, an active component of liquorice roots, had a glucocorticoid-like effect and was used to manage some autoimmune diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematous, vasculitis, and alopecia areata.[26] However, it was the first time that CGT was reported to be used to treat ARPC to our knowledge. Moreover, since ARPC is considered to be associated with some systemic diseases, the management of the coexisting disease is also beneficial. As for this patient, who got a significant amelioration without recurrence, the control of blood glucose was quite crucial.

In conclusion, we reported a rare case of ARPC with a good prognosis. It indicated that recognition and control of associated disease and CGT therapy may help to treat ARPC.

Acknowledgments

We thank all members from the Department of Dermatology of Shanghai Tenth People's Hospital for their advice and encouragement.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: ARPC = acquired reactive perforating collagenosis, KD = Kyrle disease, MMP = matrix metalloproteinase, PF = perforating folliculitis, RPC = reactive perforating collagenosis, TEE = transepithelial elimination, TGF = transforming growth factor.

CF and YW contributed equally to this paper.

This work was supported in part by grants from National Science Foundation of China (81301356), National Science Foundation of Shanghai (13ZR1432200), and the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality Grant (134119b0700).

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Rapini RP, Herbert AA, Drucker CR. Acquired perforating dermatosis. Evidence for combined transepidermal elimination of both collagen and elastic fibers. Arch Dermatol 1989; 125:1074–1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Faver IR, Daoud MS, Su WP. Acquired reactive perforating collagenosis. Report of six cases and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol 1994; 30:575–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karpouzis A, Giatromanolaki A, Sivridis E, et al. Acquired reactive perforating collagenosis: current status. J Dermatol 2010; 37:585–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhat YJ, Manzoor S, Qayoom S, et al. Familial reactive perforating collagenosis. Indian J Dermatol 2009; 54:334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mehregan AH, Schwartz OD, Livingood CS. Reactive perforating collagenosis. Arch Dermatol 1967; 96:277–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kikuchi N, Ohtsuka M, Yamamoto T. Acquired reactive perforating collagenosis: a rare association with dermatomyositis. Acta Derm Venereol 2013; 93:735–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gambichler T, Birkner L, Stücker M, et al. Up-regulation of transforming growth factor-(3 and extracellular matrix proteins in acquired reactive perforating collagenosis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2009; 60:463–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmults CA. Acquired reactive perforating collagenosis. Dermatol Online J 2002; 8:8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Rezende LN, Nuñez MG, Clavery TG, et al. Elastosis perforans serpiginosa. Indian Dermatol Online J 2014; 5:236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Faver IR, Daoud MS, Su WD. Acquired reactive perforating collagenosis: report of six cases and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol 1994; 30:575–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poliak SC, Lebwohl MG, Parris A, et al. Reactive perforating collagenosis associated with diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 1982; 306:81–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cochran R, Tucker S, Wilkin J. Reactive perforating collagenosis of diabetes mellitus and renal failure. Cutis 1983; 31:55–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kawakami T, Saito R. Acquired reactive perforating collagenosis associated with diabetes mellitus: eight cases that meet Faver's criteria. Br J Dermatol 1999; 140:521–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Basak PY, Turkmen C. Acquired reactive perforating collagenosis. Eur J Dermatol 2000; 11:466–468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saray Y, Seçkin D, Bilezikçi B. Acquired perforating dermatosis: clinicopathological features in twenty two cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2006; 20:679–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsuboi H, Katsuoka K. Characteristics of acquired reactive perforating collagenosis. J Dermatol 2007; 34:640–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ohashi T, Yamamoto T. Acquired reactive perforating collagenosis associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Dermatol 2016; doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.13357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Müller CS, Tilgen W, Rass K. Leucocytoclastic vasculitis associated with acquired reactive perforating collagenosis: a diagnostic mimicry. Dermatoendocrinology 2009; 1:229–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eriyagama S, Wee J, Ho B, et al. Acquired reactive perforating collagenosis associated with urticarial vasculitis in pregnancy. Clin Exp Dermatol 2014; 39:81–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Amano H, Nagai Y, Kishi C, et al. Acquired reactive perforating collagenosis in dermatomyositis. J Dermatol 2011; 38:1199–1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shiomi T, Yoshida Y, Horie Y, et al. Acquired reactive perforating collagenosis with the histological features of IgG4-related sclerosing disease in a patient with Mikulicz's disease. Pathol Int 2009; 59:326–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yazdi S, Saadat P, Young S, et al. Acquired reactive perforating collagenosis associated with papillary thyroid carcinoma: a paraneoplastic phenomenon? Clin Exp Dermatol 2010; 35:152–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim RH, Kwa M, Adams S, et al. Giant acquired reactive perforating collagenosis in a patient with diabetes mellitus and metastatic breast carcinoma. JAAD Case Rep 2016; 2:22–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Querings K, Balda BR, Bachter D. Treatment of acquired reactive perforating collagenosis with allopurinol. Br J Dermatol 2001; 145:174–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee FY, Chiu HY, Chiu HC. Treatment of acquired reactive perforating collagenosis with allopurinol incidentally improves scleredema diabeticorum. J Am Acad Dermatol 2011; 65:e115–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu S-f, Hu S-s. Role of compound glycyrrhizin in clinical treatment. Anhui Med Pharmaceutical J 2011; 2:052. [Google Scholar]