Abstract

Despite gaining popularity, venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VV-ECMO) remains a controversial therapy for acute respiratory failure (ARF) in adult patients due to its equivocal survival benefits. The study was aimed at identifying the preinterventional prognostic predictors of hospital mortality in adult VV-ECMO patients and developing a practical mortality prediction score to facilitate clinical decision-making.

This retrospective study included 116 adult patients who received VV-ECMO for severe ARF in a tertiary referral center, from 2007 to 2015. The definition of severe ARF was PaO2/ FiO2 ratio < 70 mm Hg under advanced mechanical ventilation (MV). Preinterventional variables including demographic characteristics, ventilatory parameters, and severity of organ dysfunction were collected for analysis. The prognostic predictors of hospital mortality were generated with multivariate logistic regression and transformed into a scoring system. The discriminative power on hospital mortality of the scoring system was presented as the area under receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC).

The overall hospital mortality rate was 47% (n = 54). Pre-ECMO MV day > 4 (OR: 4.71; 95% CI: 1.98–11.23; P < 0.001), pre-ECMO sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) score >9 (OR: 3.16; 95% CI: 1.36–7.36; P = 0.01), and immunocompromised status (OR: 2.91; 95% CI: 1.07–7.89; P = 0.04) were independent predictors of hospital mortality of adult VV-ECMO. A mortality prediction score comprising of the 3 binary predictors was developed and named VV-ECMO mortality score. The total score was estimated as follows: VV-ECMO mortality score = 2 × (Pre-ECMO MV day > 4) + 1 × (Pre-ECMO SOFA score >9) + 1 × (immunocompromised status). The AUROC of VV-ECMO mortality score was 0.76 (95% CI: 0.67–0.85; P < 0.001). The corresponding hospital mortality rates to VV-ECMO mortality scores were 18% (Score 0), 35% (Score 1), 56% (Score 2), 75% (Score 3), and 88% (Score 4), respectively.

Duration of MV, severity of organ dysfunction, and immunocompromised status were important preinterventional prognostic predictors for adult VV-ECMO. The 3 prognostic predictors could also constitute a practical prognosticating tool in patients requiring this advanced respiratory support. Physicians in ECMO institutions are encouraged to perform external validations of this prognosticating tool and make contributions to score optimization.

Keywords: extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, extracorporeal life support, acute respiratory failure, acute respiratory distress syndrome, ventilator-induced lung injury

1. Introduction

Despite an invasive therapy, venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VV-ECMO) is gaining popularity among intensivists who are frequently dealing with severe acute respiratory failure (ARF).[1,2] According to a nationwide investigation, there has been a 409% relative increase in the use of ECMO for ARF in United States between 2006 and 2011.[3] The niche of VV-ECMO for treating ARF is its capacity to promptly improve the arterial hypoxemia/hypercapnia without pulmonary manipulation.[4] The oxygenator acts as a third lung which partially refreshes the venous blood in right atrium. With this prepulmonary blood gas exchange provided by VV-ECMO, the injured lungs are allowed to rest under lung-protective ventilation. This strategy of ventilation uses low tidal volumes (VT) and low fractions of inspired oxygen (FiO2) to reduce the risks of alveolar over-distension and reabsorption atelectasis on mechanical ventilation (MV).[2,5] This temporary support of VV-ECMO may theoretically buy clinicians some more time to resolve the original cause of acute lung injury (ALI) and save the patient. The salvage rate of VV-ECMO in adult patients with severe ARF is around 50% in general.[6] However, ECMO is an expensive therapy. According to a 2007 economic report dealing with the cost of ECMO therapy in Norway, the mean estimated costs for the ECMO procedure was 73,122 USD and the total hospital course for an ECMO patient was 213,246 USD.[7] As a type of extracorporeal circulation, ECMO also carries risks of hemorrhage and systemic thromboembolism. The incidence of lethal intracranial hemorrhage is about 4% in adult patients supported by VV-ECMO.[6] Therefore, to mitigate controversies concerning the survival benefits of ECMO in adult patients with severe ARF, lots of retrospective studies have been performed to define the preinterventional prognostic factors for adult respiratory ECMO.[8–13] These preinterventional prognostic predictors may constitute a practical prognosticating tool which allows clinicians to objectively recognize the potential survival benefits associated with ECMO in individual patients and facilitate clinical communications. Among the results of these studies, the Respiratory Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Survival Prediction (RESP) Score should be the most representative.[11] Compared to other retrospective studies, the study of RESP score has the largest patient cohort (n = 2355, which was extracted from the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization international registry 2000 to 2012). The RESP Score is a 37-point (–22 to 15) scoring system with 12 variables and shows an acceptable discriminative power on hospital mortality in its training sample (area under receiver operating characteristic curve [AUROC]: 0.74). However, applying such a complex scoring system in small patient cohorts may be time-consuming and impractical.[14] Therefore, this study was aimed at developing a practical mortality prediction score which could show an acceptable prediction power of hospital mortality in a single-institution patient cohort of adult VV-ECMO.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study population

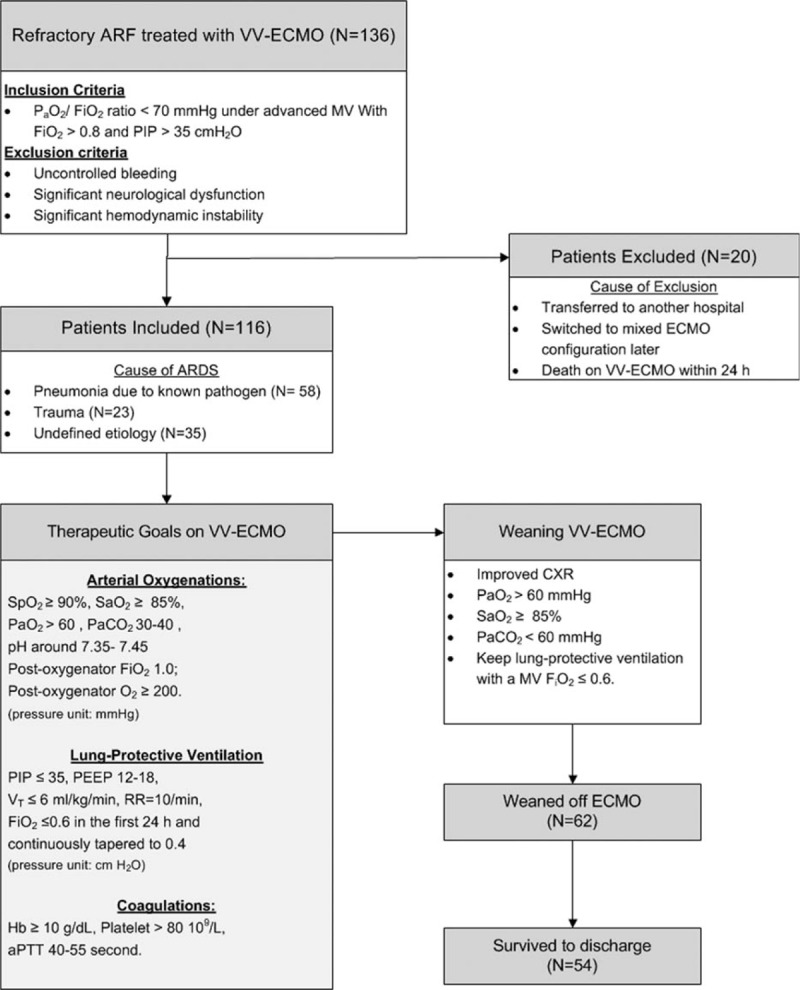

From March 2007 to December 2015, a total of 136 adult patients received VV-ECMO for advanced respiratory support at Chang Gung Memorial Hospital. The university-affiliated hospital is a tertiary referral center with 3400 beds. To reduce the heterogeneities in disease severity and patient management, 20 patients were excluded due to a family-requested transfer to another hospital (n = 1), switch to VA or mixed configuration of ECMO later (n = 5), and death on VV-ECMO in the first 24 hours (n = 14, hemorrhagic shock soon after device implantation in 5 patients and shock without obvious hemorrhagic focus in 9 patients). Therefore, only 116 among the 136 patients who had a single run of VV-ECMO and survived on VV-ECMO > 24 hours were enrolled in this retrospective study (Fig. 1). This study was conducted in accordance with the amended Declaration of Helsinki.[15] The ethics committee of the Chang Gung Medical Foundation approved the protocol (CGMF IRB no. 201600063B0C502) and waived the necessity of individual patient consent.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of patient distribution and managements during venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. aPTT = activated partial thromboplastin time, ARF = acute respiratory failure, CXR = chest radiography, FiO2 = fraction of inspired oxygen, Hb = hemoglobin, PaCO2 = arterial tension of carbon dioxide, PaO2 = arterial oxygen tension, PEEP = positive end-expiratory pressure, PIP = peak inspiratory pressure, RR = respiratory rate, SaO2 = arterial oxygen saturation, SpO2 = oxyhemoglobin saturation by pulse oximetry, VT = tidal volume, VV-ECMO = venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

2.2. Institutional criteria for adult venovenous ECMO

Our indication of VV-ECMO was a deteriorating hypoxia (a PaO2/ FiO2 ratio < 70 mm Hg) under advanced MV (FiO2 > 0.8 and peak inspiratory pressure [PIP] > 35 cmH2O). Nevertheless, VV-ECMO was contraindicated in candidates showing (1) uncontrolled hemorrhages, (2) major brain damages (intracranial hemorrhages, large infarctions, or mass), and (3) significant hemodynamic instability before the intervention with VV-ECMO.

2.3. Data collection

We retrospectively reviewed the electronic medical records in each patient and collected their important demographic and clinical data before and during the administration of VV-ECMO. These electronic medical records were included in the database of our electronic medical record system registered from 2007 to 2015. The following variables were collected: age, gender, etiologies of ARF (viral pneumonia, bacterial pneumonia, asthma, trauma and burn, aspiration pneumonia, other acute respiratory diagnoses), immunocompromised status (hematologic malignancy, solid tumor, solid organ transplantation, liver cirrhosis Child B or C, or autoimmune diseases requiring long-term steroid or other immunosuppressive therapy), nonpulmonary infection, neuromuscular blockade agents, cardiac arrest before ECMO, bicarbonate infusion, arterial blood gas measures, MV settings (MV duration, PIP and positive end-expiratory pressure [PEEP]), and the outcomes (weaning off VV-ECMO and surviving to discharge). The RESP and the sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) score were also calculated in each patient. For practical purposes, we made some differences in the RESP score to its original version.[5] First, we defined patients having an “aspiration pneumonitis” rather than a “bacterial pneumonia” if the diagnosis of “aspiration” was made. Second, we assigned the patients with fungal pneumonia to the category of bacterial pneumonia. Third, we excluded the item of nitric oxide inhalation because this information was often missing in our electronic medical record system before 2012. We also assigned a SOFA neurological assessment score to each patient according to his/her neurological status before sedation (the assumed Glasgow Coma Scale).[16]

2.4. Practice of VV-ECMO in adult with respiratory failure

We have thoroughly described our techniques and therapeutic protocol of VV-ECMO in our previous publications.[17–20]Figure 1 summarizes the major therapeutic goals of our VV-ECMO. Our ECMO devices include a driving pump (Capiox emergent bypass system [Terumo, Tokyo, Japan] or Bio-console 560 system [Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN]), an oxygenator (Capiox-SX [Terumo, Tokyo, Japan] or Hilite 7000 [Medos, Stolberg, Germany]), and 2 vascular cannulae (DLP Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN). We conduct VV-ECMO via percutaneous cannulation of the common femoral vein (inflow, with a cannula of 19–23 French) and the right internal jugular vein (outflow, with a cannula of 17–21 French). After implantation of VV-ECMO, we initially maximize the sweep gas flow (10 L/min, pure oxygen) to rapidly remove the CO2 and gradually increase the ECMO pump flow to achieve a steady flow that carries the best pulse oximetry-detected oxyhemoglobin saturation (SpO2). To rest the lung on VV-ECMO, we change the setting of MV to a lung-protective level step-by-step. At first, we use a pressure-control mode with a PIP ≤ 35 cmH2O and a moderate PEEP (often 12–16 cmH2O) to obtain an estimated tidal volume 4–6 mL/kg/min on VV-ECMO. Then we take arterial and the postoxygenator blood samples to adjust the sweep gas flow and the MV FiO2. We also adjust the pump speed dynamically to provide a best SpO2 (> 90%) and SaO2 (> 85%) in order to gradually taper the PIP to 30 cmH2O and MV FiO2 to 0.4. The arterial PaO2 was kept ≥ 60 mm Hg and the pH was kept in the normal range. The hemoglobin is kept ≥ 10 g/dL to increase the capacity of oxygenation. A modest anticoagulation on VV-ECMO with systemic heparinization is also kept except in hemorrhagic patients. The therapeutic range of activated partial thromboplastin time is 40 to 55 seconds. In patients showing significant improvements, we would try to wean the patient from VV-ECMO as long as the arterial oxygenation could be maintained under lung-protective ventilation with an MV FiO2 ≤ 0.6.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS for Windows (Version 15.0, SPSS, Inc., IL). For all analyses, the statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. The independent t test was used for univariate comparisons of the independent numerical variables. If the numerical variables were not normally distributed, the Mann–Whitney U test was used for univariate comparisons. The chi-square or Fisher's exact test was used to compare the categorical variables. Data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for numerical variables with normal distribution or median (interquartile range) for numerical variables without normal distribution. The categorical data were presented as number (percentage). The multiple logistic regression analysis with backward stepwise selection was used to find the independent predictors for hospital mortality. All variables with a P < 0.05 in univariate tests were included in the regression model. Before being recruited to the regression model, all numerical variables were dichotomized on the basis of cut-off values that were determined by the ROC curve analysis. The Hosmer–Lemeshow test and the c-index were used to assess the model's goodness-of-fit and discrimination of hospital mortality. Then a weighted scoring system was developed on the basis of the estimated coefficient (β) of each independent predictor to facilitate clinical applications of the prediction model.[21] The value was “1” if a dichotomized predictor was true or otherwise “0.” The final score, as a weighted summation of each value, was calculated for each patient and tested for the discriminative power on hospital mortality as the value of AUROC.

3. Results

3.1. Univariate comparisons

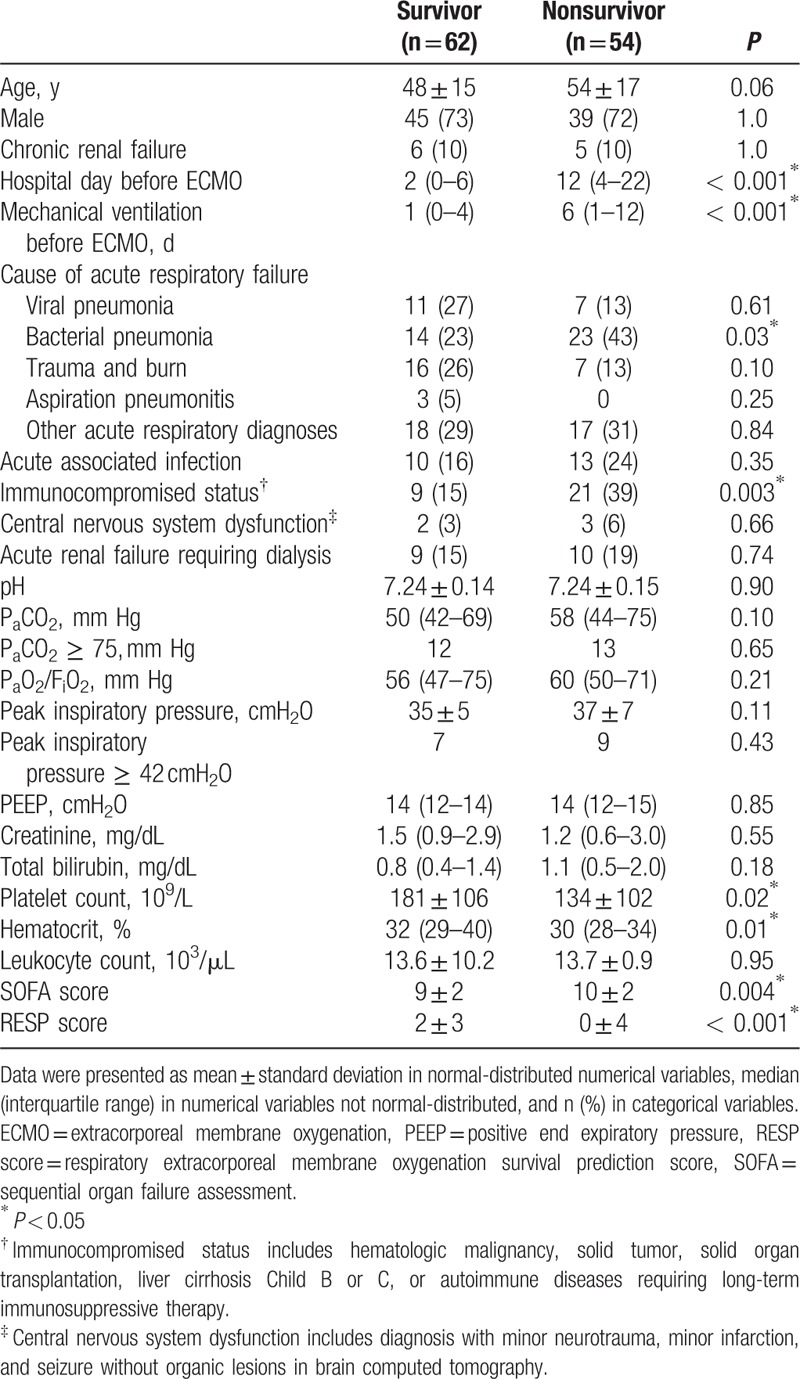

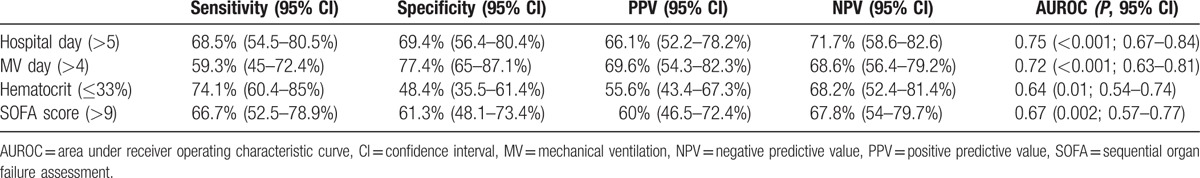

The mean age of the 116 patients was 51 ± 16 years and 76% (n = 84) of them were male. The causes of ARF were categorized into 5 groups: bacterial pneumonia (n = 37; 3 were fungal pneumonia, and the top 3 found bacteria were Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Acinetobacter baumannii), viral pneumonia (n = 18; all influenza A), trauma, or inhalation injury (n = 23), aspiration pneumonitis (n = 3), and others (n = 35). The “others” group included patients with pneumonia without identifiable pathogens (n = 22), pulmonary hemorrhage caused by autoimmune vasculitis (n = 4), pulmonary edema due to acute on chronic renal failure or after percutaneous cardiac interventions (n = 7), neurogenic pulmonary edema after cerebral aneurysm intervention (n = 1), and pneumonitis after near-drowning (n = 1). The median duration of MV before VV-ECMO was 2.5 (IQR: 0–8) days. The mean values of the pre-ECMO SOFA score and RESP score were 9 ± 2 and 1 ± 4, respectively. The ECMO weaning rate was 72% (n = 84) and the overall surviving to hospital discharge rate was 53% (n = 62). Ten patients died of major hemorrhagic complications which included intracranial hemorrhages (n = 4), intra-abdominal/retroperitoneal hemorrhages (n = 2), diffuse mucosal or gastrointestinal tract bleedings (n = 3), and hemothorax (n = 1) during the support of VV-ECMO. The other nonsurvivors (n = 46) showed a dependence on either VV-ECMO or MV, and died of multiple organ failure with sepsis. The median values of ECMO stay and hospital stay were 9 (5–15) and 43 (24–65) days, respectively. Table 1 shows the results of univariate comparisons of the baseline characteristics between the survivor and nonsurvivors. According to Table 1, 7 pre-ECMO variables had a significantly different distribution between the survivors and nonsurvivors. Among the 7 variables, 5 were numerical (pre-ECMO hospital stay, pre-ECMO MV day, pre-ECMO hematocrit, pre-ECMO SOFA score, and pre-ECMO RESP score) and 2 were categorical (bacterial pneumonia and immunocompromised status). Table 2 shows the diagnostic accuracies and AUROCs of the 4 numerical variables (pre-ECMO hospital stay, pre-ECMO MV day, pre-ECMO hematocrit, and pre-ECMO SOFA score) at their cut-off points before being included in the regression model. The RESP score was not included to the regression model as our purpose was to develop a new scoring system.

Table 1.

Information before venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

Table 2.

Diagnostic accuracies and areas under receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) of the numerical risk factors at their cut-off points.

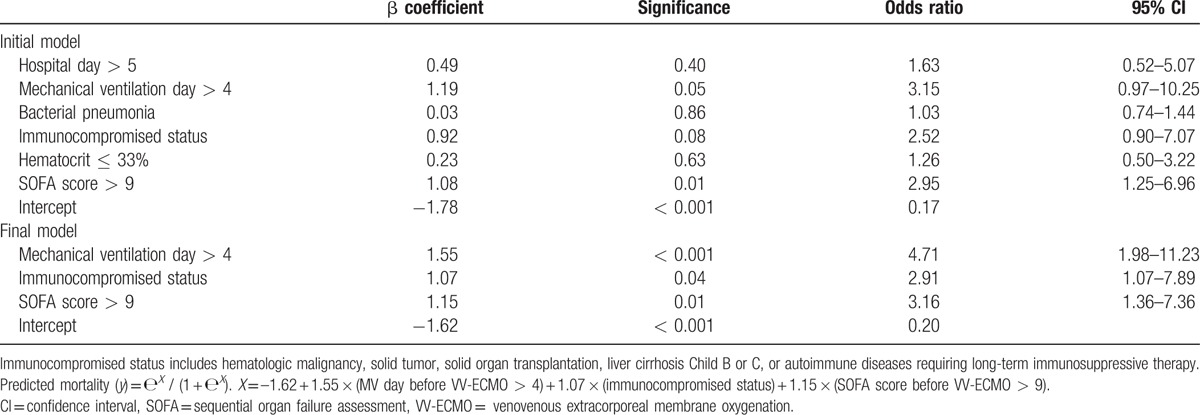

3.2. Multivariate analysis

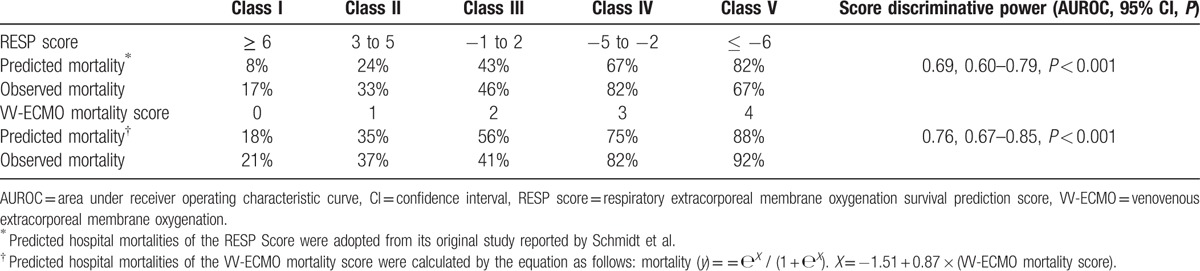

Table 3 shows the independent predictors of hospital mortality in adult VV-ECMO. The institutional mortality prediction model was presented as follows: predicted mortality (y) = еX / (1 + еX). X = –1.62 + 1.55 × (MV day before VV-ECMO > 4) + 1.07 × (immunocompromised status) + 1.15 × (SOFA score before VV-ECMO > 9). The model explained 30.2% (Nagelkerke R2) of the variance in hospital mortality and correctly classified 72.4 % of the cases (sensitivity: 53.7 %; specificity: 88.7 %). This predictive model also fit the dataset well (Hosmer–Lemeshow test: χ 2 = 2.39, P = 0.79; c-index: 0.76, P < 0.001). Then, the prediction model was transformed into a scoring system that included 3 dichotomized independent predictors. The estimated coefficient (β) weight of each independent risk factor was transformed into the scoring system after some modification. As all β values were between 1.0 and 1.5, the weight was assigned “1” for β ≤ 1.5 or “2” for β> 1.5. The formula of our institutional score was as follows: VV-ECMO mortality score = (pre-ECMO MV day > 4) × 2 + (immunocompromised status) × 1 + (SOFA score before VV-ECMO > 9) × 1. This 5-point scoring system (score 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4) was tested by logistic regression method again to obtain the mathematical equation for calculating the predictive mortality of each score. The equation of the VV-ECMO mortality score was presented as follows: predicted mortality (y) = еX / (1+еX). X = –1.51 + 0.87 × (VV-ECMO mortality score). Both the β estimations of the intercept and the VV-ECMO mortality score were statistically significant (P < 0.001). Table 4 shows the estimated and observed hospital mortality of VV-ECMO mortality score and RESP score in our patient cohort. The AUROCs of the VV-ECMO mortality score and the RESP score were 0.76 and 0.69, respectively. The difference of the 2 AUROCs of the VV-ECMO mortality score and RESP score was not statistically significant when being processed with the nonparametric approach suggested by Hanley and McNeil.[22]

Table 3.

Factors associated with hospital mortality in multivariate logistic regression. All variables record the patients’ characteristics before the implantation of venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VV-ECMO). The variables were recruited to the model with backward stepwise selection.

Table 4.

Predicted and observed hospital mortalities of the RESP Score and the VV-ECMO mortality score in the patient cohort.

4. Discussion

This study was aimed at developing a simple preinterventional scoring system to predict hospital mortality associated with VV-ECMO used for adult respiratory failure. The ultimate purpose of such a tool is to help clinicians to recognize poor-prognostic candidates for VV-ECMO and prepare alternative solutions for them.[11] For example, venoarterial (VA) ECMO may be a more useful life support than VV-ECMO for patients that have both respiratory and hemodynamic failures. Keeping the patient treated with conventional MV alone is still a practical opinion in candidates with a high risk of bleeding. In some matched cohort studies of adult respiratory failure which compare the survival benefits between conventional MV and VV-ECMO, the patients treated with conventional MV alone still have a hospital survival rate of 60% to 47% if they have flu-related ARF.[23,24] However, this hospital survival rate may drop to 25% if the etiology of ARF is not limited to flu.[20]

Although the case-matched studies can offer a balanced report on the survival benefits of VV-ECMO, they failed to inform readers about the choice for the “nonmatchable” patients. Stratifying the ECMO-treated patients into risk categories for hospital mortality according to their preinterventional presentations may be an important strategy to shorten this knowledge gap. By scoring the patients, clinicians may know where their patient falls within the risk spectrum of hospital mortality related to adult respiratory ECMO.[11] Thus, we developed VV-ECMO mortality score to meet the clinical requirement. The score comprised 3 preinterventional variables which were important in clinical practice. Pre-ECMO immunocompromised status reflects a difficulty in controlling the original pathogen. However, young adults or pediatric patients with hematologic malignancies may show an acceptable survival rate with ECMO used for respiratory failure. This survival rate may be able to reach up to 50% in few reports;[25,26] nevertheless, it could not be copied in studies including adult patients with solid tumors.[27,28] The severity of pre-ECMO organ dysfunctions is a well-documented prognostic predictor of hospital mortality in all ECMO-treated patients.[29] Traditionally, patients become candidates for ECMO only when they are considered to be “sick enough.” The window of survivability is narrow and closely related to the residual organ functions. Therefore, after adjusting the mortality risk to the severity of pre-ECMO hypoxemia, the ELSO guideline for adult respiratory failure loosens up the restriction of pre-ECMO PaO2/FiO2 (from 100 to 150 mm Hg) now.[30] This is an important conceptual change in ECMO practices, from “recruiting the one sick enough” to “recruiting the one who will be reasonably benefited.” Duration of pre-ECMO MV is also a known prognostic predictor of hospital mortality in adult respiratory ECMO.[8,11,12] Limiting the duration of pre-ECMO MV to 7 days or less has become a consensus in prospective trials.[9,31] The reason why the increased duration of pre-ECMO MV contributes to the mortality of adult respiratory ECMO is not exactly known. Actually, patients with ALI and a prolonged duration of pre-ECMO MV may have an increased chance to be exposed to ventilator-induced lung injury (VILI). According to a recent report, patients with a pre-ECMO MV > 7 days tend to have a significant reduction of pulmonary compliance and difficulties to wean off VV-ECMO.[17] Therefore, rather than the actual limitation for MV days before VV-ECMO, markers representing the existence of significant VILI may be more practical to the decision of introducing VV-ECMO.

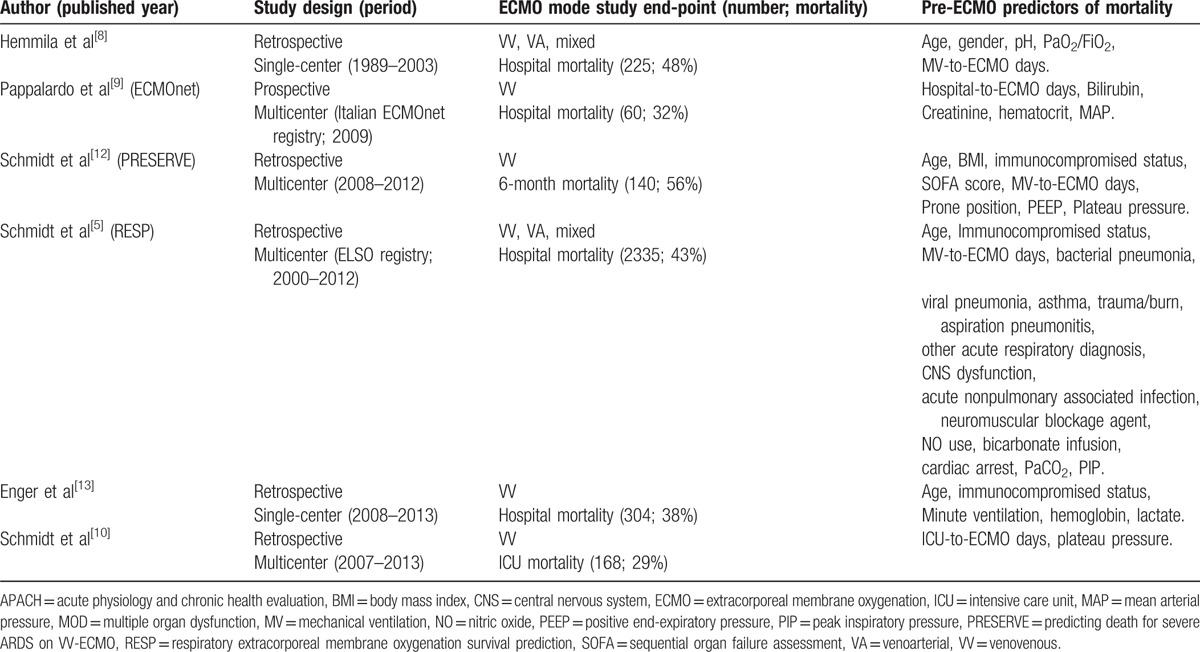

Compared to the RESP score, VV-ECMO mortality score had fewer predictive variables and showed a noninferior discriminative power of hospital mortality in an institutional patient cohort. However, due to the small sample size, it is not suitable to perform internal validations to understand the performance of VV-ECMO mortality score outside the training sample. To understand the universality of the predictive variables of VV-ECMO mortality score in general practices, we performed a thorough search in PubMed for researches focusing on this topic. This literature review should offer valuable knowledge about the prognostic predictors in adult respiratory ECMO and is summarized in Table 5. Table 5 enrolled 6 studies and 3232 patients in total, with an overall mortality of 43%. All the included research articles were published after 2000 from different databases and provide information about prognostic predictors of mortality associated with adult respiratory ECMO. All the prognostic predictors are generated with logistic regression. According to Table 5, the most common prognostic predictors of mortality in adult respiratory ECMO were age, pre-ECMO MV days, immunocompromised status, and the severity of acute organ dysfunction before ECMO. The severity of acute organ dysfunction can be measured by separated or comprehensive estimations of specific clinical data. Based on the abovementioned information, the predictive variables in VV-ECMO mortality score are key prognostic factors in adult respiratory ECMO. With the help of VV-ECMO mortality score, clinicians may estimate the mortality risk associated with VV-ECMO quickly, and then communicate with the family or colleagues for the next step. However, score calibrations may be needed during external validations with institutional data, as the cut-off point and the weight of a specific predictive variable may be different among institutions. Therefore, physicians in ECMO institutions are encouraged to perform external validations of VV-ECMO mortality score and find their optimal versions through the process.

Table 5.

Recent publications focused on developing a mortality prediction model in adult respiratory extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

The major limitations of this study are its retrospective design and small sample size. It was a pilot study and needs to be validated in different settings and populations. This study did not provide a comprehensive discussion of adult respiratory ECMO as only patients treated with VV-ECMO were included. Further collaborated and prospective studies are necessary to define the optimal timing and configuration of adult respiratory ECMO in specific scenarios.

5. Conclusion

Duration of MV, severity of organ dysfunction, and immunocompromised status were important preinterventional prognostic predictors for adult VV-ECMO. These predictors may constitute a practical prognosticating tool in patients requiring this advanced respiratory support. Such a prognosticating tool may also serve as a platform to discuss the optimal respiratory support for individual patients with severe respiratory failure.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: ARF = acute respiratory failure, AUROC = area under receiver operating characteristic curve, CESAR = conventional ventilatory support versus extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, ECMO = extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, ELSO = Extracorporeal Life Support Organization, FiO2 = fraction of inspiratory oxygen, MV = mechanical ventilation, PaCO2 = arterial carbon dioxide tension, PaO2 = arterial oxygen tension, PEEP = positive end-expiratory pressure, PIP = peak inspiratory pressure, RESP = respiratory extracorporeal membrane oxygenation survival prediction, SaO2 = arterial oxygen saturation, SD = standard deviation, SOFA = sequential organ failure assessment, SpO2 = oxyhemoglobin saturation by pulse oximetry, VA = venoarterial, VV = venovenous.

Authorship: MYW and YTC equally contributed to conception and design of the study, interpretation of the data, and drafted the manuscript. YSC contributed to the literature review and acquisition of the data. CCH and PJL contributed to interpretation of the data and designed the ventilation protocol. MYW contributed to interpretation of the data, performed statistical analysis, and was responsible for the final product. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

The authors have no funding and conflicts of interest to disclose.

Competing Interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Combes A, Brodie D, Bartlett R, et al. Position paper for the organization of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation programs for acute respiratory failure in adult patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014; 190:488–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goligher EC, Doufle G, Fan E. Update in mechanical ventilation, sedation, and outcomes 2014. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015; 191:1367–1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rush B, Wiskar K, Berger L, et al. Trends in extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for the treatment of acute respiratory distress syndrome in the United States. J Intensive Care Med 2016; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI:10.1177/0885066616631956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.MacLaren G, Combes A, Bartlett RH. Contemporary extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for adult respiratory failure: life support in the new era. Intensive Care Med 2012; 38:210–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmidt M, Pellegrino V, Combes A, et al. Mechanical ventilation during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Crit Care 2014; 18:203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paden ML, Conrad SA, Rycus PT, et al. Extracorporeal Life Support Organization Registry Report 2012. ASAIO J 2013; 59:202–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mishra V, Svennevig JL, Bugge JF, et al. Cost of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: evidence from the Rikshospitalet University Hospital, Oslo, Norway. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2010; 37:339–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hemmila MR, Rowe SA, Boules TN, et al. Extracorporeal life support for severe acute respiratory distress syndrome in adults. Ann Surg 2004; 240:595–605.discussion 605–597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pappalardo F, Pieri M, Greco T, et al. Predicting mortality risk in patients undergoing venovenous ECMO for ARDS due to influenza A (H1N1) pneumonia: the ECMOnet score. Intensive Care Med 2013; 39:275–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmidt M, Stewart C, Bailey M, et al. Mechanical ventilation management during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for acute respiratory distress syndrome: a retrospective international multicenter study. Crit Care Med 2015; 43:654–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmidt M, Bailey M, Sheldrake J, et al. Predicting survival after extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe acute respiratory failure. The Respiratory Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Survival Prediction (RESP) score. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014; 189:1374–1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmidt M, Zogheib E, Roze H, et al. The PRESERVE mortality risk score and analysis of long-term outcomes after extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. Intensive Care Med 2013; 39:1704–1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Enger T, Philipp A, Videm V, et al. Prediction of mortality in adult patients with severe acute lung failure receiving veno-venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: a prospective observational study. Crit Care 2014; 18:R67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Senussi MH. Respite from the RESP score. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014; 190:962–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Medical A. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013; 310:2191–2194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Livingston BM, Mackenzie SJ, MacKirdy FN, et al. Should the pre-sedation Glasgow Coma Scale value be used when calculating Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation scores for sedated patients? Scottish Intensive Care Society Audit Group. Crit Care Med 2000; 28:389–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu MY, Huang CC, Wu TI, et al. Venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for acute respiratory distress syndrome in adults: prognostic factors for outcomes. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016; 95:e2870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu MY, Lin PJ, Tseng YH, et al. Venovenous extracorporeal life support for posttraumatic respiratory distress syndrome in adults: the risk of major hemorrhages. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2014; 22:56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chiu LC, Tsai FC, Hu HC, et al. Survival predictors in acute respiratory distress syndrome with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Ann Thorac Surg 2015; 99:243–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsai HC, Chang CH, Tsai FC, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome with and without extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: a score matched study. Ann Thorac Surg 2015; 100:458–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu MY, Lin PJ, Lee MY, et al. Using extracorporeal life support to resuscitate adult postcardiotomy cardiogenic shock: treatment strategies and predictors of short-term and midterm survival. Resuscitation 2010; 81:1111–1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hanley JA, McNeil BJ. A method of comparing the areas under receiver operating characteristic curves derived from the same cases. Radiology 1983; 148:839–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pham T, Combes A, Roze H, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for pandemic influenza A(H1N1)-induced acute respiratory distress syndrome: a cohort study and propensity-matched analysis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013; 187:276–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Noah MA, Peek GJ, Finney SJ, et al. Referral to an extracorporeal membrane oxygenation center and mortality among patients with severe 2009 influenza A(H1N1). JAMA 2011; 306:1659–1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gow KW, Heiss KF, Wulkan ML, et al. Extracorporeal life support for support of children with malignancy and respiratory or cardiac failure: the extracorporeal life support experience. Crit Care Med 2009; 37:1308–1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wohlfarth P, Ullrich R, Staudinger T, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in adult patients with hematologic malignancies and severe acute respiratory failure. Crit Care 2014; 18:R20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gow KW, Lao OB, Leong T, et al. Extracorporeal life support for adults with malignancy and respiratory or cardiac failure: The Extracorporeal Life Support experience. Am J Surg 2010; 199:669–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu MY, Wu TI, Tseng YH, et al. The feasibility of venovenous extracorporeal life support to treat acute respiratory failure in adult cancer patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015; 94:e893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu MY, Lin PJ, Tsai FC, et al. Impact of preexisting organ dysfunction on extracorporeal life support for non-postcardiotomy cardiopulmonary failure. Resuscitation 2008; 79:54–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Extracorporeal Life Support Organization (ELSO). ELSO Guideline for Adult Respiratory Failure. 2013. http://www.elso.org. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peek GJ, Mugford M, Tiruvoipati R, et al. Efficacy and economic assessment of conventional ventilatory support versus extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe adult respiratory failure (CESAR): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2009; 374:1351–1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]