Abstract

Background:

Pulmonary veno-occlusive disease (PVOD) is a rare and devastating cause of pulmonary arterial hypertension with a non-specific clinical presentation and a relatively specific presentation in high-resolution thoracic CT scan images. Definitive diagnosis is made by histological examination in previous. According to the 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines, detection of a mutation in the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 alpha kinase 4 (EIF2AK4) without histological confirmation is recommended to validate the diagnosis of PVOD.

Methods:

We report the case of a 27-year-old man who was admitted for persistent cough and dyspnea that had lasted for 5 months and had developed and experienced progressive dyspnea for the last 2 months. The echocardiogram and right heart catheterization without vasodilator challenge confirmed the diagnosis of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Other tests, such as high-resolution thoracic CT scan, V/Q scan, pulmonary function test with diffusion capacity, and blood tests, excluded other associated diseases which could have caused pulmonary hypertension.

Results:

The initial diagnosis at admission was idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension and an oral vasodilator (sildenafil) was given. However, the dyspnea subsequently worsened, and the patient was transferred to a regional lung transplant center, where he died of heart failure 1 week later. Using exome sequencing, we found an EIF2AK4 mutation, which was sufficient to confirm the diagnosis of PVOD.

Conclusion:

This is the first reported case of EIF2AK4 mutation in PVOD in a Chinese patient population. We found the frameshift EIF2AK4 mutation c.1392delT (p.Arg465fs) in this case. Up to now, there has been a paucity of data on this rare disease, and the exact role of EIF2AK4 loss-of-function mutations in the pathogenesis of PVOD is still unknown. More investigations should be conducted in the future.

Keywords: EIF2AK4, pulmonary arterial hypertension, pulmonary veno-occlusive disease

1. Introduction

Pulmonary veno-occlusive disease (PVOD) is categorized into a separate pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH)-related group in the current classification of pulmonary hypertension.[1] The condition is histologically characterized by widespread fibrous intimal proliferation of septal veins and preseptal venules and is frequently associated with pulmonary capillary dilatation and proliferation.[2] The clinical presentation is typically nonspecific, including dyspnea, fatigue, and cough. Hence, hemodynamic evaluation by right heart catheterization is necessary to confirm the existence of PAH. Usually, high-resolution CT scanning of the chest shows diffuse bilateral confluent ground-glass opacities, septal line thickening, and enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes. In addition, pulmonary function tests exhibit diminished diffusing capacity. The prognosis for these patients is poor. Lung transplantation has been recognized as the only curative therapy for PVOD.[2]

The diagnosis is confirmed by histological examination of either postmortem or explanted lung tissue in previous. The elevation in the values of both pulmonary venous and arterial pressure poses a risk of life-threatening bleeding associated with lung biopsy and is thus not recommended. Data from whole genome sequencing from a recent investigation demonstrated that mutations in eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 alpha kinase 4 (EIF2AK4) were present in all familial PVOD and in 25% of the sporadic PVOD cases. The results support the conclusion that EIF2AK4 is a major causal gene for PVOD.[3] The 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines recommend that patients with sporadic or familial PVOD should be tested for EIF2AK4 mutations. The presence of a EIF2AK4 mutation is sufficient to confirm the diagnosis of PVOD without performing a hazardous lung biopsy for histological confirmation.[1] Using exome sequencing, we detected a mutation in EIF2AK4 in 1 PAH patient who had clinical and radiological signs that were strongly suggestive of PVOD but who did not tolerate lung biopsy. This is the first reported case of an EIF2AK4 mutation in a PVOD case in a Chinese population.

2. Case report

A 27-year-old man, nonsmoker, with no pertinent medical, social, or family history presented was brought to the hospital for persistent cough and dyspnea for 5 months and progressive dyspnea for 2 months. His job was to frame and sell new oil paintings. On admission the physical examination showed a body temperature of 36.2 °C, heart rate of 120/minute, respiratory rate of 23/minute, and blood pressure of 102/66 mm Hg. He had an accentuated second pulmonic heart sound. The 6-minute walk distance was 300 m. The arterial blood gases test indicated that PaO2 was 55 mm Hg and PaCO2 was 42 mm Hg in breathing room air. The results of the hematologic and biochemical tests were within the normal range. The concentration of brain natriuretic peptide was 469 ng/L. The transthoracic echocardiogram revealed a dilated right ventricle with a normal left ventricular function and an estimated right ventricular systolic peak pressure of 68 mm Hg. The chest CT scan images showed diffuse bilateral confluent ground-glass opacities, septal line thickening, and enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes (Fig. 1). The ventilation/perfusion lung scan result was negative for pulmonary embolism. Right heart catheterization showed severe pulmonary arterial hypertension with a mean pulmonary artery pressure at 50 mm Hg, and pulmonary artery wedge pressure of 13 mm Hg.

Figure 1.

(A) Intralobular septal thickening observed in the chest CT scan. (B) Diffuse bilateral confluent ground-glass opacities displayed in the chest CT scan. (C) Enlarged mediastinal lymph node seen in the chest CT scan. CT = computed tomography.

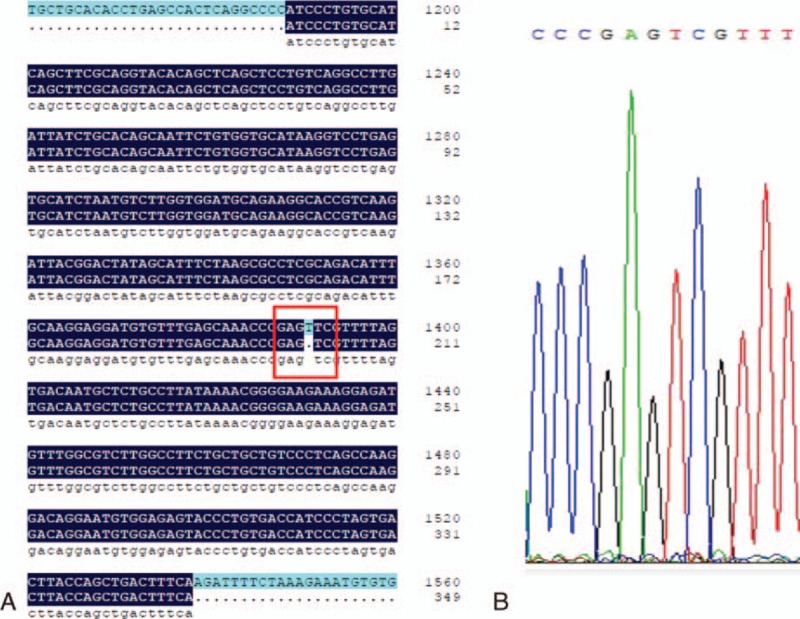

The initial diagnosis was idiopathic PAH, and the patient was discharged with oxygen therapy, oral diuretics, and warfarin. After 10 days of treatment with sildenafil, the dyspnea worsened. The administration of higher-flow oxygen therapy was necessary. The concentration of brain natriuretic peptide (2705 ng/L) was higher than that of the previous hospital admittance. This response to pulmonary arterial vasodilator strongly suggested the diagnosis of PVOD. Sildenafil was stopped immediately, escalating doses of loop diuretic were initiated, and the patient was transferred to a regional lung transplant center. Unfortunately, he died of heart failure 1 week later. As described in a previous report,[4] exome sequencing for blood sample of this patient was performed. Briefly, we first captured exomes with the Agilent Sure Select kit (×7 Human all Exon U4; Agilent Technologies Inc., Colorado Springs, CO), and then sequenced them with 2 × 100 base-pair paired-end reads on an HiSeq2000 sequencer (Illumina, Inc.). Sequence was aligned to Hg19 and variants were called with the Genome Analysis Tool kit (Version 1.6). If the variants had a quality score<10, it would be removed to avoid false positives. Next, mutations were confirmed by Sanger Sequencing. Sequences containing mutations in EIF2AK4 were amplified and Sanger-sequenced. In this case, we found an EIF2AK4 mutation using exome sequencing for the analysis of patient's blood sample. It was a sequence of the coding sequence region in exon 9 of EIF2AK4, and the mutation was c.1392delT (p.Arg465fs) (Fig. 2). According to the 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines, the presence of EIF2AK4 mutation was sufficient to confirm a diagnosis of PVOD without a histological confirmation.

Figure 2.

(A) Sequence of the CDS region in exon 9 of EIF2AK4. (B) The c.1392delT (p.Arg465fs) mutation. CDS = coding sequence.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient.

3. Discussion

PVOD is a rare and often fatal cause of pulmonary arterial hypertension. It shares several clinical and hemodynamic similarities with idiopathic PAH, which can easily lead to misdiagnosis between these 2 conditions. The diagnosis is based on clinical suspicion, physical examination, pulmonary function test, and radiological findings, with a definitive diagnosis based on histological confirmation. Clinical presentation including dyspnea, fatigue, and cough is nonspecific.[5] Physical examination may reveal digital clubbing and bibasal crackles on lung auscultation, these could being distinguishable from PAH.[5] The pulmonary function test shows much lower DLCO levels than in other forms of PAH.[2,5] Typical findings from high-resolution CT of the chest are the presence of centrilobular ground-glass opacities, subpleural thickened septal lines, and mediastinal lymphadenopathy.[2,5] Definitive diagnosis is made by histological examination of either postmortem or explanted lung tissue and bronchoscopic transbronchial lung biopsy is not recommended. Most importantly, vasodilators with PAH therapy must be used with great caution because of the high risk of severe drug-induced pulmonary edema.[5] Oxygen therapy will improve symptoms and reduce the likelihood of hypoxic-vasoconstriction. Diuretics is recommended for management of right-ventricular failure. Slow increases in intravenous epoprostenol doses could improve clinical and hemodynamic parameters in PVOD patients at 3 to 4 months without commonly causing pulmonary edema, and may be a useful bridge to urgent lung transplantation.[6] Without definitive treatment, the prognosis is poor. The 1-year mortality is as high as 72% and the mean survival is estimated at 1 to 2 years.[5,7]

In a previous study, 2 pathogenic mutations in EIF2AK4 were identified in a pulmonary capillary hemangiomatosis (PCH) family, 2 of the 10 sporadic PCH patients, and 1 sporadic patient was homozygous for the frameshift mutation c.1392delT (p.Arg465fs), which was identical to that in our patient.[4] In the current classification of pulmonary hypertension, PVOD is grouped with PCH in a diagnostic group 1′.[1] Histopathological manifestations show that PVOD originates in a widespread vascular obstructive process of the pulmonary venules and small veins, and PCH begins its development in a widespread vascular obstructive process of the alveolar capillary bed. However, there is still a debate as to whether these are 2 distinct diseases or varied expressions of a single disorder because they share many similarities in their pathologic features and clinical characteristics as well as the risk of drug-induced pulmonary edema with PAH therapy.[5,8] It has been proposed that PCH could be a secondary angioproliferative process caused by postcapillary obstruction of PVOD.[9]EIF2AK4 belongs to a family of kinases that regulate angiogenesis in response to cellular stress. It is primarily a sensor of amino acid availability and a regulator of changes in gene expression in response to amino acid deprivation.[10] It could also be activated by viral infections, UV irradiation, and glucose deprivation.[11–14] Some investigations have demonstrated that EIF2AK4 is also involved in hypoxia-induced eIF2α phosphorylation and mediate cell adaptation to hypoxic stress. Reduced phosphorylation of eIF2α by knocking out either EIF2AK4 suppresses hypoxia-induced G1 arrest and promotes apoptosis accompanied by activation of p53 signaling cascade. EIF2AK4 has been shown to protect cells against hypoxia by limiting p53 levels and transcriptional activity, at least in some tumor cells in vitro.[15] As hypoxia can induce pulmonary vascular remodeling, vascular wall thickening, and lumen narrowing, it can result in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Therefore, mutations in EIF2AK4 could supposedly lead to suppression of its protective activity against apoptosis and hinder the recovery of cells from hypoxia, and thus induce and worsen pulmonary arterial hypertension in PVOD patients.

In an earlier investigation, the response of EIF2AK4+/+ and EIF2AK4–/– mice to a long-term (24 weeks) leucine-imbalanced diet (EDΔLeu) was studied, and the degree of protein oxidation in the liver was determined. In response to EDΔLeu, the EIF2AK4–/– mice exhibited an increase in protein carbonylation, which is a marker of oxidative stress that is important for pulmonary hypertension development.[16] The results suggested that EIF2AK4 and its downstream signaling pathway can play a critical role in the prevention of oxidative damage. Moreover, it was demonstrated that the EIF2AK4/eIF2a/ATF4 (activating transcription factor 4) pathway is essential for the induction of TRB3 (tribbles homolog 3) gene transcription in response to a leucine-deficient diet.[17] Downregulation of TRIB3 has been shown to inhibit BMP (bone morphogenetic protein)-mediated cellular responses and may lead to PAH in the case of BMPR2 (bone morphogenetic protein receptor type II) haploinsufficiency.[18,19] The angiogenic pathology of PVOD, which is characterized by uncontrolled proliferation of pulmonary venules, is still unknown. The role of EIF2AK4 mutations in pulmonary vascular remodeling should be explored in the future.

At present, the etiology and risk factors associated with PVOD remain poorly understood. Occupational exposures have been proposed as a potential risk factor for PVOD. A case-control investigation by Montani et al[20] found that PVOD was significantly associated with occupational exposure to organic solvents, with trichloroethylene being the main agent implicated. Therefore, the absence of significant trichloroethylene exposure was related to the younger age and the high prevalence of harboring EIF2AK4 mutations.[20] According to this study, both genetic background and environmental exposure may influence the phenotypic expression of the disease.[20] Previous studies have indicated that the exposure to toxins, such as cigarette smoke and chemotherapeutic agents, is associated with the development of PVOD.[5,21,22] Mitomycin-C (MMC) therapy was reported to be a potent inducer of PVOD in humans and rats. In rats, MMC administration was associated with the dose-dependent depletion of pulmonary EIF2AK4 content and decreased smad1/5/8 signaling. Amifostine prevented the development of MMC-induced PVOD.[21] Another report reviewed 37 cases of chemotherapy-associated PVOD from the French PH network and literature. They found that 83.8% of the exposure in the cases was to alkylating agents, mostly represented by cyclophosphamide (43.2%). In addition, the histopathological assessment confirmed the significant pulmonary venous involvement in 3 different animal models (mouse, rat, and rabbit), which was highly suggestive of PVOD.[22] Therefore, the frequent contact of our patient with fresh oil paintings in the recent 2 years was likely to have contributed to the pathogenesis of PVOD.

4. Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of EIF2AK4 mutation in PVOD in a Chinese patient population. We found the frameshift EIF2AK4 mutation c.1392delT (p.Arg465fs) in this case. Up to now, there has been a paucity of data on this rare disease, and the exact role of EIF2AK4 loss-of-function mutations in the pathogenesis of PVOD is still unknown. More investigations should be conducted in the future.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: BMP = bone morphogenetic protein, BMPR2 = bone morphogenetic protein receptor type II, EDΔLeu = leucine-imbalanced diet, EIF2AK4 = eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 alpha kinase 4, MMC = mitomycin-C, PAH = pulmonary arterial hypertension, PCH = pulmonary capillary hemangiomatosis, PVOD = pulmonary veno-occlusive disease, TRB3 = tribbles homolog 3.

Funding: This study was supported by research grant 81570043 from the National Natural Science Foundation of China andresearch grant LY14H010001 from the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province in China.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Galiè N, Humbert M, Vachiery JL, et al. 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Heart J 2016; 37:67–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Montani D, Price LC, Dorfmuller P, et al. Pulmonary veno-occlusive disease. Eur Respir J 2009; 33:189–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eyries M, Montani D, Girerd B, et al. EIF2AK4 mutations cause pulmonary veno-occlusive disease, a recessive form of pulmonary hypertension. Nat Genet 2014; 46:65–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Best DH, Sumner KL, Austin ED, et al. EIF2AK4 mutations in pulmonary capillary hemangiomatosis. Chest 2014; 145:231–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Montani D, Achouh L, Dorfmuller P, et al. Pulmonary veno-occlusive disease: clinical, functional, radiologic, and hemodynamic characteristics and outcome of 24 cases confirmed by histology. Medicine 2008; 87:220–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Montani D, Jaïs X, Price LC, et al. Cautious epoprostenol therapy is a safe bridge to lung transplantation in pulmonary veno-occlusive disease. Eur Respir J 2009; 34:1348–1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holcomb BW, Jr, Loyd JE, Ely EW, et al. Pulmonary veno-occlusive disease: a case series and new observations. Chest 2000; 118:1671–1679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Humbert M, Maître S, Capron F, et al. Pulmonary edema complicating continuous intravenous prostacyclin in pulmonary capillary hemangiomatosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998; 157:1681–1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lantuejoul S, Sheppard MN, Corrin B, et al. Pulmonary veno-occlusive disease and pulmonary capillary hemangiomatosis: a clinicopathologic study of 35 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2006; 30:850–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deval C, Chaveroux C, Maurin AC, et al. Amino acid limitation regulates the expression of genes involved in several specific biological processes through GCN2-dependent and GCN2-independent pathways. FEBS J 2009; 276:707–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berlanga JJ, Ventoso I, Harding HP, et al. Antiviral effect of the mammalian translation initiation factor 2alpha kinase GCN2 against RNA viruses. EMBO J 2006; 25:1730–1740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krishnamoorthy J, Mounir Z, Raven JF, et al. The eIF2alpha kinases inhibit vesicular stomatitis virus replication independently of eIF2alpha phosphorylation. Cell Cycle (Georgetown, TX) 2008; 7:2346–2351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grallert B, Boye E. The Gcn2 kinase as a cell cycle regulator. Cell Cycle (Georgetown TX) 2007; 6:2768–2772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ye J, Kumanova M, Hart LS, et al. The GCN2-ATF4 pathway is critical for tumour cell survival and proliferation in response to nutrient deprivation. EMBO J 2010; 29:2082–2096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu Y, Laszlo C, Liu W, et al. Regulation of G(1) arrest and apoptosis in hypoxia by PERK and GCN2-mediated eIF2 alpha phosphorylation. Neoplasia 2010; 12:61–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chaveroux C, Lambert-Langlais S, Parry L, et al. Identification of GCN2 as new redox regulator for oxidative stress prevention in vivo. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2011; 415:120–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carraro V, Maurin AC, Lambert-Langlais S, et al. Amino acid availability controls TRB3 transcription in liver through the GCN2/eIF2(/ATF4 pathway. PLoS One 2010; 5:e15716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chan MC, Nguyen PH, Davis BN, et al. A novel regulatory mechanism of the bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling pathway involving the carboxyl-terminal tail domain of BMP type II receptor. Mol Cell Biol 2007; 27:5776–5789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davies RJ, Holmes AM, Deighton J, et al. BMP type II receptor deficiency confers resistance to growth inhibition by TGF-β in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells: role of proinflammatory cytokines. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2012; 302:604–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Montani D, Lau EM, Descatha A, et al. Occupational exposure to organic solvents: a risk factor for pulmonary veno-occlusive disease. Eur Respir J 2015; 46:1721–1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perros F, Günther S, Ranchoux B, et al. Mitomycin-induced pulmonary veno-occlusive disease: evidence from human disease and animal models. Circulation 2015; 132:834–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ranchoux B, Gunther S, Quarck R, et al. Chemotherapy-induced pulmonary hypertension: role of alkylating agents. Am J Pathol 2015; 185:356–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]