Abstract

Rationale:

We report on a stroke patient who showed change of the ascending reticular activating system (ARAS) concurrent with recovery from a vegetative state (VS) to a minimally conscious state (MCS), which was demonstrated on diffusion tensor tractography (DTT).

Patient concerns:

A 59-year-old male patient underwent CT-guided stereotactic drainage 3 times for management of intracerebral hemorrhage and intraventricular hemorrhage.

Diagnosis:

After 4 months from onset, when starting rehabilitation, the patient showed impaired consciousness, with a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 6 and a Coma Recovery Scale-Revised score of 2. At 10 months after onset, his GCS score had recovered to 11 with a GRS-R score of 20, and he was able to perform rock–scissors–paper using his right hand according to verbal command.

Interventions:

On 10-month DTT, marked increased neural connectivity of the thalamic intralaminar nucleus (ILN) to the cerebral cortex was observed in both prefrontal cortexes and the right thalamus compared with 4-month DTT. However, no significant change was observed in the lower dorsal ARAS between the pontine reticular formation (PRF) and the thalamic ILN. In addition, the reconstructed lower ventral ARAS between the PRF and hypothalamus had disappeared in both hemispheres on 10-month DTT.

Outcomes:

Change of the ARAS was demonstrated in a stroke patient who showed recovery from a VS to an MCS.

Lessons:

It appeared that the prefrontal cortex and thalamus, which showed increased neural connectivity, contributed to recovery from a VS to an MCS in this patient.

Keywords: ascending reticular activating system, consciousness, diffusion tensor tractography, minimally conscious state, stroke, vegetative state

1. Introduction

Human consciousness consists of arousal and awareness, which is controlled by action of the ascending reticular activating system (ARAS). Vegetative state (VS) is a condition of preservation of arousal with complete unawareness of self or environment, while a minimally conscious state (MCS) is a condition in which minimal self or environmental awareness is demonstrated.[1–3] Elucidation of the neural structures involved in the recovery from VS to MCS has been an important topic in neuroscience because it can provide useful information for prediction of prognosis of VS and guidelines for neurorehabilitation in patients with VS. Several studies have reported on this topic; however, it has not been clearly elucidated so far.[4–8]

In this study, we report on change of the ARAS concurrent with recovery from a VS to an MCS in a stroke patient.

2. Case report

A 59-year-old male patient underwent CT-guided stereotactic drainage 3 times for management of intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) and intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) from onset and ventriculoperitoneal shunt operation for hydrocephalus at 6 weeks after onset at the department of neurosurgery of a university hospital (Fig. 1A). After 4 months from onset, he was transferred to the rehabilitation department of the university hospital (Fig. 1B). The patient showed impaired consciousness, with a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 6 (eye opening: 2, best verbal response: 1, and best motor response: 3) and a Coma Recovery Scale-Revised score of 2 (auditory function: 0, visual function: 0, motor function: 1, verbal function: 0, communication: 0, and arousal: 1).[9,10] He underwent comprehensive rehabilitative therapy, which included neurotropic drugs (modafinil, methylphenidate, amantadine, levodopa, zolpidem, and baclofen), physical therapy, and occupational therapy.[11] After 1-month rehabilitation at the university hospital, he underwent rehabilitation including the same neurotropic drugs at another rehabilitation hospital. His consciousness had recovered with the passage of time. At 10 months after onset, his GCS score had recovered to 11 (eye opening: 4, best verbal response: 1, and best motor response: 6) with a Coma Recovery Scale-Revised score of 20 (auditory function: 4, visual function: 5, motor function: 6, verbal function: 1, communication: 1, and arousal: 3) (Fig. 1C). As a result, he was able to perform rock–scissors–paper using his right hand according to verbal command. The patient's wife provided signed, informed consent, and the study protocol was approved by our Institutional Review Board.

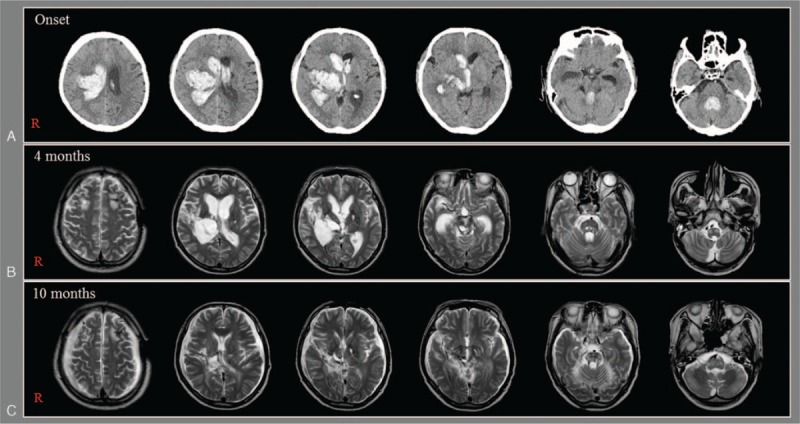

Figure 1.

(A) Brain CT images at onset show intracerebral hemorrhage in the right thalamus and basal ganglia and intraventricular hemorrhage. (B and C) Brain MR images at 4 and 10 months after onset show leukomalactic lesions in the right basal ganglia and thalamus, and both brainstems.

2.1. Diffusion tensor imaging

DTI data were acquired 2 times (4 and 10 months after onset) using a 6-channel head coil on a 1.5-T Philips Gyroscan Intera (Philips, Best, the Netherlands) with single-shot echo-planar imaging. Imaging parameters were as follows: acquisition matrix = 96 × 96, reconstructed to matrix = 192 × 192, field of view = 240 × 240 mm2, the repetition time = 10,398 ms, the echo time = 72 ms, parallel imaging reduction factor (SENSE factor) = 2, echo-planar imaging factor = 59, b = 1000 s/mm2, slice gap = 0 mm, and a slice thickness = 2.5 mm.

The Oxford Centre for Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Brain (FMRIB) Software Library was used for analysis of DTI data. Affine multiscale 2-dimensional registration was used for correction of head motion effect and image distortion due to eddy current. FMRIB Diffusion Software (Oxford, United kingdom) with routines option (0.5-mm step lengths, 5000 streamline samples, and curvature thresholds = 0.2) was used for fiber tracking. Three portions of the ARAS were reconstructed by selection of fibers passing through regions of interest (ROIs). For analysis of the dorsal lower ARAS, the seed ROI was placed on the pontine reticular formation (PRF) at the level of the trigeminal nerve entry zone and the target ROI was placed on the thalamic intralaminar nucleus (ILN) at the level of the commissural plane.[12] For reconstruction of the ventral lower ARAS, the seed ROI was placed on the PRF and the target ROI was placed on the hypothalamus.[13] For analysis of the connectivity of the thalamic ILN, the seed ROI was placed on the thalamic ILN.[12] Out of 5000 samples generated from the seed voxel, results for contact were visualized at a threshold for the ARAS of a minimum of 2 and for connectivity of the thalamic ILN of 15 streamlined through each voxel for analysis.

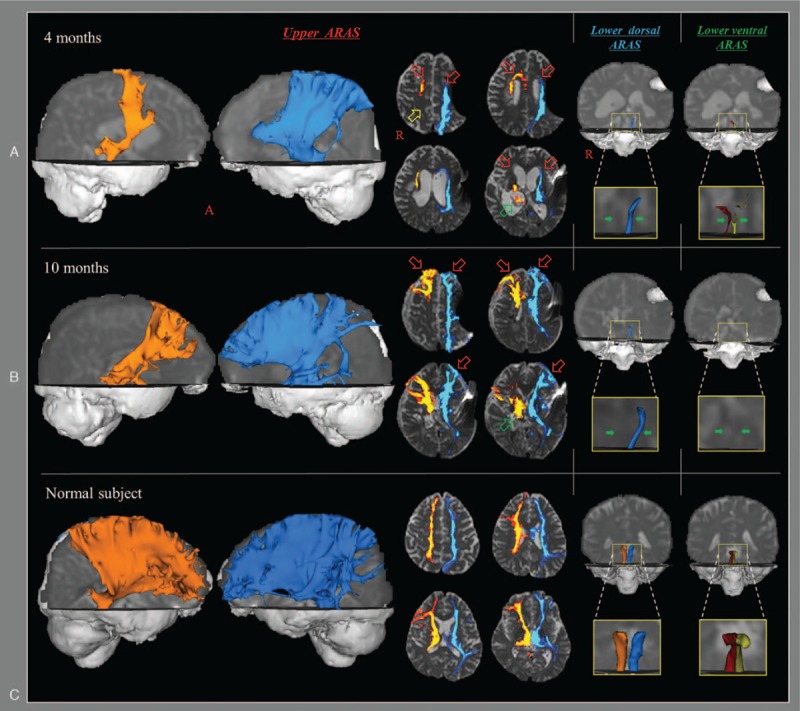

On 4-month diffusion tensor tractography (DTT), decreased neural connectivity of the upper ARAS between the thalamic ILN and the cerebral cortex was observed in both prefrontal cortexes, right parietal cortex, both basal forebrain, and right thalamus (Fig. 2). The lower dorsal ARAS between the PRF and the ILN was absent on the right side and thin on the left side. The lower ventral ARAS between the PRF and the hypothalamus was thin on both sides. By contrast, on 10-month DTT, markedly increased neural connectivity of the upper ARAS was observed in both prefrontal cortexes and the right thalamus compared with 4-month DTT. However, no significant change was observed in the lower dorsal ARAS, and the reconstructed lower ventral ARAS had disappeared in both hemispheres on 10-month DTT.

Figure 2.

Results of diffusion tensor tractography (DTT) for the ascending reticular activating system (ARAS) of the patient and a normal subject (56-year-old male). On 4-month DTT, decreased neural connectivity of the upper ARAS between the intralaminar nucleus (ILN) and the cerebral cortex was observed in both prefrontal cortexes (red arrows), right parietal cortex (yellow arrow), and right thalamus (green arrow). The lower dorsal ARAS between the pontine reticular formation (PRF) and the ILN was absent on the right side and thinner on the left side compared with the normal subject. The lower ventral ARAS between the PRF and the hypothalamus was thinner on both sides compared with the normal subject. By contrast, on 10-month DTT, marked increased neural connectivity of the upper ARAS was observed in both prefrontal cortexes (red arrows) and right thalamus (green arrows) compared with 6-month DTT. However, no significant change was observed in the lower dorsal ARAS (green arrows), and the reconstructed lower ventral ARAS (green arrows) had disappeared in both hemispheres on 10-month DTT. PRF = pontine reticular formation, ILN = intralaminar nucleus.

3. Discussion

In this study, using DTT, change of the ARAS was demonstrated in a stroke patient who showed recovery from VS to MCS after comprehensive rehabilitation was evaluated. VS is regarded as permanent 3 months after nontraumatic brain injury or 12 months after traumatic injury[2]; therefore, because more than 4 months had passed since the onset of ICH and IVH, this patient corresponded to a persistent VS. He recovered to an MCS after rehabilitation: at 10 months after onset, the patient was able to perform hand tasks such as rock–scissors–paper according to verbal command. Results of comparison of the change of the ARAS on DTT were as follows: the neural connectivity to the prefrontal cortex and thalamus was increased, no significant change of the lower dorsal ARAS, and aggravation of the lower ventral ARAS. Consequently, in this patient, it appeared that the increased connectivity to the prefrontal cortex and thalamus, which are important areas of the brain for consciousness, were responsible for recovery from a VS to an MCS.[4–7,11,13,14] On the other hand, preservation of the lower dorsal ARAS could be important for consciousness, whereas the lower ventral ARAS appeared not to contribute to the recovery of awareness.

Several studies have attempted to elucidate the neural difference between VS and MCS.[4–7] In 2010, Fernandez-Espejo et al,[5] who investigated differences in the subcortical white matter, thalamus, and brainstem in 25 patients with VS or MCS, using diffusion weighted imaging, found differences in the subcortical white matter and thalamus in VS and MCS patients, but not in the brainstem. Other studies have reported on several supratentorial neural areas that are important for MCS which are different from those for VS.[4–7] These neural areas comprise the prefrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, parietal cortex, basal forebrain, thalamus, and hypothalamus.[4,6,7] Thus, our results showing increased neural connectivity to the prefrontal cortex and thalamus without significant change in the lower dorsal and ventral ARAS appear to coincide with those of previous studies.[4–7]

In conclusion, change of the ARAS was demonstrated in a stroke patient who showed recovery from a VS to an MCS. It appeared that the prefrontal cortex and thalamus, which showed increased neural connectivity, contributed to recovery from a VS to an MCS in this patient. We believe that our study has an implication in the development of therapeutic strategies for patients with VS. However, the limitation of DTT should be considered: it may underestimate the fiber tracts due to regions of fiber complexity and crossing.[15]

Footnotes

Abbreviations: ARAS = ascending reticular activating system, DTT = diffusion tensor tractography, GCS = Glasgow Coma Scale, ICH = intracerebral hemorrhage, IVH = intraventricular hemorrhage, MCS = minimally conscious state, PRF = pontine reticular formation, ROIs = regions of interest, VS = vegetative state.

Author contributions: SHJ—study concept and design, manuscript development, and writing; CHC—acquisition and analysis of data; YJJ and YSS—study concept and design, acquisition and analysis of data, and manuscript authorization.

Funding/support: The work was supported by the National Research Foundation (NRF) of Korea Grant funded by the Korean Government (MSIP) (2015R1A2A2A01004073).

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- [1].[No authors listed]. Medical aspects of the persistent vegetative state (2). The multi-society task force on PVS. N Engl J Med 1994;330:1572–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Laureys S, Owen AM, Schiff ND. Brain function in coma, vegetative state, and related disorders. Lancet Neurol 2004;3:537–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Giacino JT, Ashwal S, Childs N, et al. The minimally conscious state: definition and diagnostic criteria. Neurology 2002;58:349–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Laureys S, Faymonville ME, Luxen A, et al. Restoration of thalamocortical connectivity after recovery from persistent vegetative state. Lancet 2000;355:1790–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Fernandez-Espejo D, Bekinschtein T, Monti MM, et al. Diffusion weighted imaging distinguishes the vegetative state from the minimally conscious state. Neuroimage 2011;54:103–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Jang SH, Lee HD. Ascending reticular activating system recovery in a patient with brain injury. Neurology 2015;84:1997–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Jang S, Kim S, Lee H. Recovery from vegetative state to minimally conscious state: a case report. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2016;95:e63–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Jang SH, Kim SH, Lim HW, et al. Recovery of injured lower portion of the ascending reticular activating system in a patient with traumatic brain injury. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2015;94:250–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Teasdale G, Jennett B. Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness. A practical scale. Lancet 1974;2:81–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Giacino JT, Kalmar K, Whyte J. The jfk coma recovery scale-revised: measurement characteristics and diagnostic utility. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2004;85:2020–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Schiff ND. Recovery of consciousness after brain injury: a mesocircuit hypothesis. Trends Neurosci 2010;33:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Yeo SS, Chang PH, Jang SH. The ascending reticular activating system from pontine reticular formation to the thalamus in the human brain. Front Hum Neurosci 2013;7:416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Jang SH, Kwon HG. The ascending reticular activating system from pontine reticular formation to the hypothalamus in the human brain: a diffusion tensor imaging study. Neurosci Lett 2015;590:58–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Silva S, Alacoque X, Fourcade O, et al. Wakefulness and loss of awareness brain and brainstem interaction in the vegetative state. Neurology 2010;74:313–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Yamada K, Sakai K, Akazawa K, et al. MR tractography: a review of its clinical applications. Magn Reson Med Sci 2009;8:165–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]