Abstract

Patients with chronic diseases often face financial barriers to optimize their health. These financial barriers may be related to direct healthcare costs such as medications or self-monitoring supplies, or indirect costs such as transportation to medical appointments. No known framework exists to understand how financial barriers impact patients’ lives or their health outcomes.

We undertook a grounded theory study to develop such a framework. We used semistructured interviews with a purposive sample of participants with cardiovascular-related chronic disease (hypertension, diabetes, heart disease, or stroke) from Alberta, Canada. Interview transcripts were analyzed in triplicate, and interviews continued until saturation was reached.

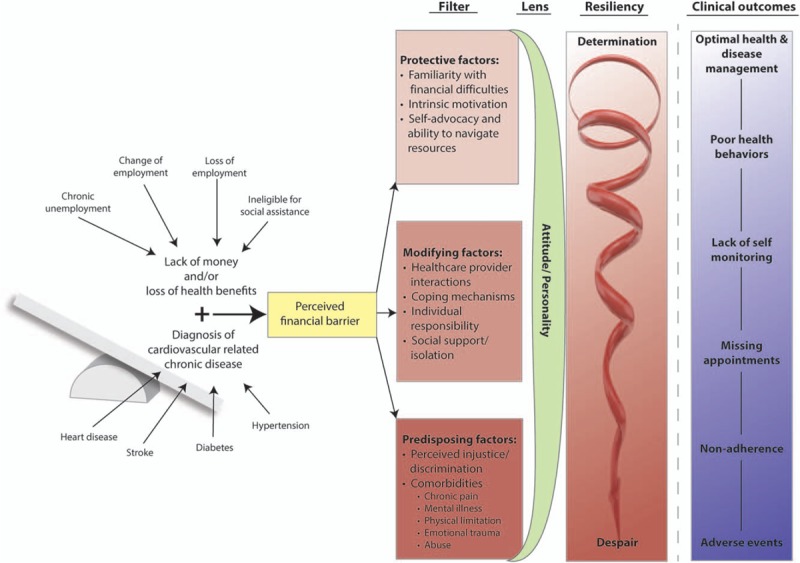

We interviewed 34 participants. We found that the confluence of 2 events contributed to the perception of having a financial barrier—onset of chronic disease and lack of income or health benefits. The impact of having a perceived financial barrier varied considerably. Protective, predisposing, or modifying of factors determined how impactful a financial barrier would be. An individual's particular set of factors is then shaped by their worldview. This combination of factors and lens determines one's degree of resiliency, which ultimately impacts how well they cope with their disease.

The role of financial barriers is complex. How well an individual copes with their financial barriers is intimately tied to resiliency, which is related to the composite of a personal circumstances and their worldview. Our framework for understanding the experience of financial barriers can be used by both researchers and clinicians to better understand patient behavior.

Keywords: barriers to care, finances, financial barriers, framework, grounded theory, health services accessibility, healthcare disparities, qualitative research

1. Introduction

Cardiovascular-related chronic diseases such as heart attacks, strokes, and diabetes remain among the most common causes of morbidity and mortality in North America.[1] This remains the case in spite of remarkably effective medical[2] and lifestyle therapies[3] to delay the onset and progression of cardiovascular disease.

Patients with these conditions may face a variety of barriers to receiving these effective therapies.[4] In particular, many studies have demonstrated significant associations between lower income levels and adverse health outcomes.[5,6] However, since some individuals have assets beyond their income and others have significant fixed expenses despite a reasonable income, other measures may be more useful determinants than income. The perception of a financial barrier among patients may be a helpful marker as this includes consideration of both an individual patient's assets and financial demands. Our previous research has demonstrated that despite public health insurance, 12% to 20% of Canadians with cardiovascular-related chronic diseases experience financial barriers to care.[7] This is largely driven by the limited scope of public health insurance and the fact that outpatient medications for many chronic conditions are not universally covered. Even when patients are insured, they may face substantial copayments when trying to access medications at their pharmacy.[8,9] We have also demonstrated that those who perceive having a financial barrier are more likely to self-report adverse outcomes such as requiring emergency department visits and hospitalization for their chronic disease.[7,10] Similarly, in the United States, Rahimi et al[11] demonstrated a significant association between perception of having a financial barrier and rehospitalization, as well as lower quality of life amongst myocardial infarction patients.

The presumptive mechanism for these findings is via cost-related nonadherence: those who experience financial barriers may be less likely to take prescription medications appropriately due to cost constraints,[7] resulting in poorer disease management and higher use of acute care services. However, the link between the perception of having a financial barrier and adverse health outcomes remains speculative and unproven.

Typically, conceptual or theoretical frameworks are used to help elucidate mechanisms of complex human behaviors. While there are frameworks for understanding access to care in a general sense, at present there are no known frameworks or theories in the published literature which describe the experience of patients who have financial barriers. In a separate publication,[11] we describe related existing frameworks on tangentially related topics, such as patient health beliefs,[13] access to care,[14] socioeconomic position,[15] and healthcare utilization.[16] However, financial barriers are only a small piece among a multitude of factors considered in these various models. We feel that a novel framework for specifically understanding the experience of perceived financial barriers would be a valuable resource for researchers, clinicians, and policy-makers as they attempt to minimize the adverse impact of financial barriers on patients’ lives and health status.

2. Methods

As our overarching objective was to develop a novel framework for understanding the experience of having a perceived financial barrier, we chose to utilize grounded theory methodology to ensure that the resultant framework would be based on individuals’ experiences. Grounded theory enables theory or model development through a rigorous process of collecting and interrogating qualitative data for the purpose of understanding the phenomenon of interest.[17–19]

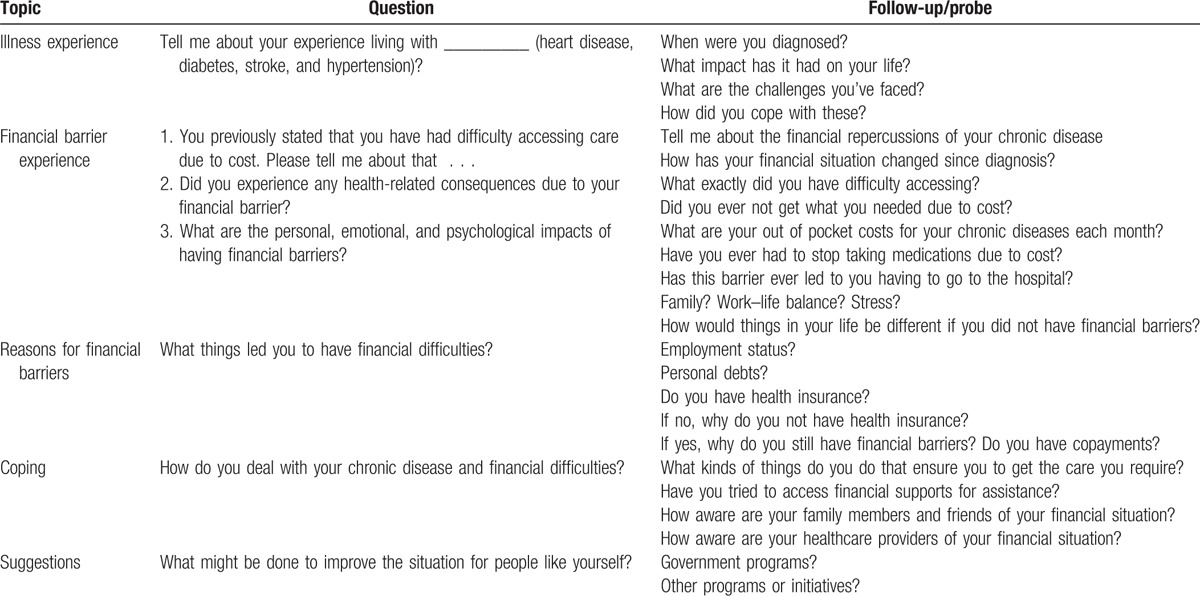

Our full methodology is published separately in our study protocol.[12] In brief, using an open-ended question guide (Table 1), we interviewed a purposive sample of individuals with cardiovascular-related chronic diseases (i.e., heart disease, diabetes, stroke, or hypertension) who had experienced financial barriers (defined by the question: In the past 12 months did you have difficulty paying for services, equipment, medications for your chronic conditions?). Participants were recruited from family physician and specialist physician offices as well as pre-existing research databases of participants with these conditions.

Table 1.

Interview guide.

Interviews were digitally recorded verbatim and transcribed using standard linguistic conventions. As per our prespecified protocol, with the assistance of qualitative data analysis software (NVivo 10, QSR International; Doncaster, Australia), 3 experienced reviewers (DJTC, PL, and research assistant) used grounded theory coding techniques (i.e., open, focused, and axial coding) to inductively analyze the data, which were collected until no new major themes were found (i.e., saturation was reached). A fourth reviewer (KK-S) adjudicated any discrepancies in interpretation between the analysts.

We employed member checking to enhance the rigor of the study by presenting our interpretation of study results to 10 participants in 2 separate focus group meetings to obtain their feedback and ensure that their thoughts and opinions were represented accurately in the model. We presented our findings to participants and received their feedback, which was incorporated into the final framework.

Ethics approval was granted from the University of Calgary's Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board, and all study procedures were in accordance with this approval and with the Canadian Tri-Council Policy Statement guidelines. Informed consent was received verbally over the telephone for interviews, and written consent was obtained for focus group participation.

3. Results

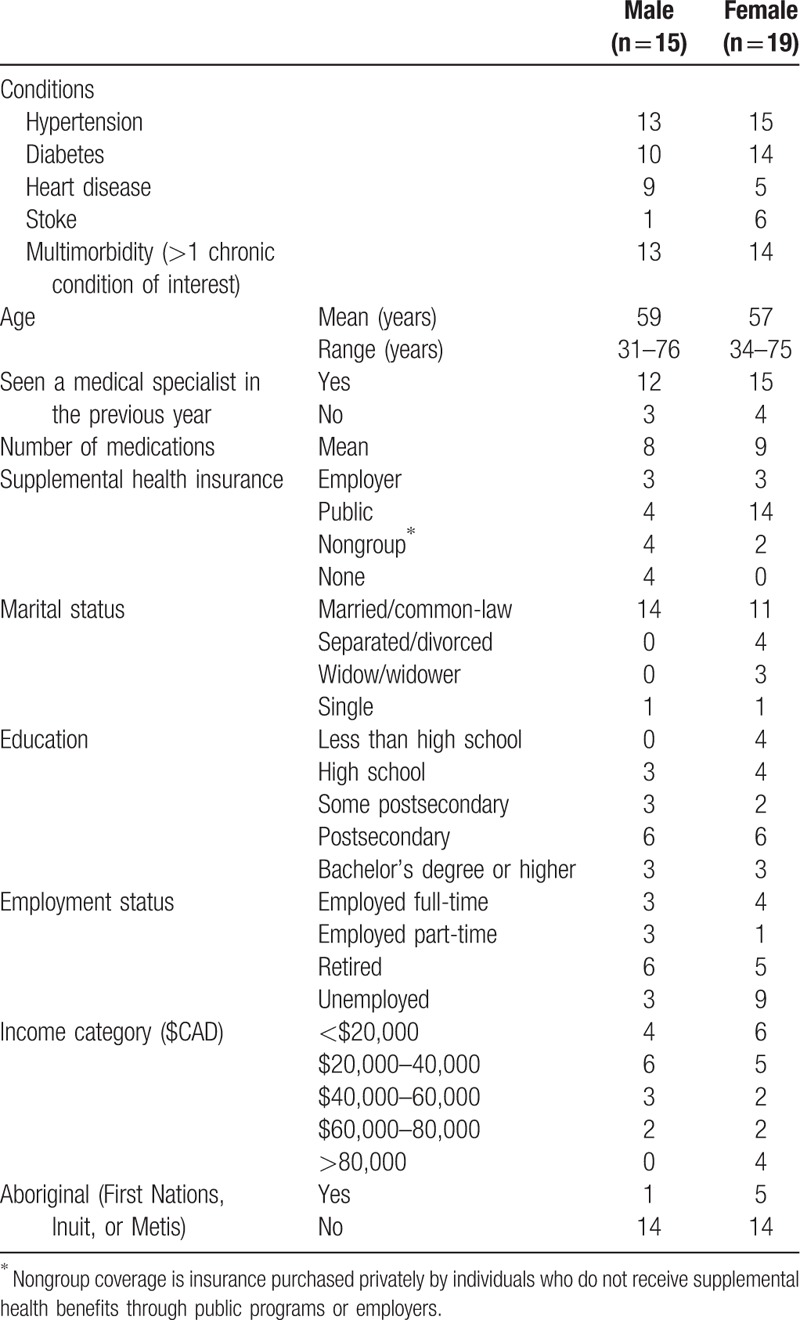

We completed 34 in-depth interviews—10 in person (at the University) and 24 over the telephone—between only the interviewer and participant (spouse was present in 2 interviews). Five individuals declined participation or dropped out. These interviews averaged 49 minutes (range: 33–92 minutes) in length. Repeat interviews were not conducted. We interviewed 15 men and 19 women with a variety of chronic conditions (Table 2). Most participants had hypertension (28/34) and/or diabetes (24/34), with 28/34 having more than 1 condition. The participants’ ages ranged from 31 to 76 years. The majority (30/34) had some form of supplemental health insurance to cover outpatient prescription medications.

Table 2.

Participant characteristics.

Through our analytic process, we came to understand that there are 2 key elements for understanding the experience of financial barriers which must be included in the model. These include explanations of

-

(1)

The factors that contribute to a given patient coming to experience financial barriers and

-

(2)

The process that determines how impactful a financial barrier is on a patient's life, given considerable heterogeneity in terms of the importance of such barriers on individuals’ lives.

The overall framework is depicted in Fig. 1. Below, we describe the components of the framework with supporting quotations embedded (italicized).

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework for understanding the development and role of financial barriers for patients with cardiovascular-related chronic diseases.

3.1. Contributors to the perception of financial barriers

We heard overwhelmingly consistent stories of how participants came to experience financial barriers. This was attributed to the confluence of 2 factors: diagnosis/onset of their cardiovascular-related chronic disease and lack of money or health benefits. Participants reported “managing” financially despite lacking health benefits or having limited income, until the heart attack, stroke, or diagnosis of diabetes—after which their lives were changed to a state of constant struggle.

On the other hand, some participants were able to financially manage their chronic disease until they lost their jobs or retired, or a change of employment resulted in a loss of health benefits which precipitated a problematic financial barrier:

Up until October of last year, it [diabetes] really didn’t have any financial bearing on me whatsoever. I’ve always had really good medical plans through my work, even if I had to pay a little bit it was not big deal …. I took a contract job and I don’t have benefits and now I’m finding out exactly how much money in diabetes supplies and insulin that I’m using …. It's huge and it's taking a real toll on me financially.

These problems were often compounded. Numerous participants described how their chronic condition was linked to or resulted in their loss of employment and worsening of their subsequent financial barrier. These stories included employers not tolerating participants’ requirements to eat regularly (e.g., those with diabetes on insulin) or employers not continuing to provide jobs for contract workers after required time away (e.g., following a heart attack):

They don’t wanna be flexible, they just don’t. I told my employer about everything that's going on. I don’t have to disclose anything and I did because we’re like a family. They’re always like: “we’re family … we love our employees.” Yeah, well, apparently not when it comes down to push or shove.

This element of the process is portrayed to the left-hand side of our framework (Fig. 1). We have chosen the image of a balance to represent that participants often stated that they were doing just fine until one of these changes (diagnosis of chronic condition or loss of financial resources) tipped them over to the situation where they then had to face a significant financial barrier.

3.2. Impact of financial barriers

As opposed to the uniformity of experiences about how financial barriers arose, we heard heterogeneous stories describing the impact that financial barriers had on participants. While some participants were profoundly affected by their financial barrier—with significant social, emotional, and physical health repercussions—others stated that it's pinching but it's not exactly hurting yet. Upon discovering this wide variety in the impact of perceived financial barriers, we were left to consider and explore the reasons that one individual may be more affected than another. We heard that patients’ experiences of having a financial barrier passes through a series of filters and a lens, which contribute to the degree of resiliency displayed, determining the impact of the financial barrier and may ultimately influence clinical outcomes.

3.2.1. Filters

Participants’ experience dealing with financial barriers was shaped initially by a series of factors that we have labeled filters. These were personal, interpersonal, and experiential factors which could act in a protective fashion (to minimize the negative impact of financial barriers); a predisposing fashion (amplifying negative repercussions); or in a modifying fashion (having the potential to act as either protective or predisposing factors). Any given participant may have had any combination of these factors The aggregate of these filters is the starting point of how much potential for negative impact a financial barrier may have.

3.3. Protective factors

3.3.1. Familiarity with financial difficulties

We heard from a number of participants that one's familiarity with living with limited resources and financial constraints played a significant role in how impactful a financial barrier could be in one's life. Participants who grew up in settings where finances were “tight” spoke of having learned to budget, prioritize, and live with minimal excess. These experiences, in turn, were helpful when they faced future financial constraints: Learning as a kid growing up that we need to budget because we don’t have that money has been a Godsend. We were raised what to prioritize first.

3.3.2. Intrinsic motivation

Several participants told us how their own self-motivation to maintain or improve their health protected them against the full impact of financial barriers:

I’ve talked to my doctor and I already told him that I’m gonna be very aggressive about this condition. I want it controlled completely by diet. I do not want to be taking medications for the rest of my life. If I have to I will but I’m gonna minimize them to the extent that I can.

Intrinsic motivation was often manifested by a willingness to prioritize healthcare needs above nearly all else. Even in the face of very significant financial constraints, those who were self-motivated often described being able to meet their healthcare needs, largely through prioritization and budgeting: we cut other stuff out, whatever we have to cut out …. I will never let my medications suffer. I need my medications.

3.3.3. Navigating resources and self-advocacy

Participants identified a number of programs and subsidies which played important protective roles in their lives. These programs included supplemental medication insurance, food banks, hospital and government programs for the provision of diabetes supplies, support for adaptive equipment, compassionate relief from pharmaceutical companies, and subsidies for fitness passes.

To varying extents, each participant described resources upon which they relied to enable them to cope with their financial barrier. Despite this, only a minority of participants demonstrated that they were adept at navigating these various resources to ensure that their needs were met. Others seemed to struggle and only accessed resources when they were directly given to them: I don’t know who else to access money from, I just …. I haven’t a clue. Irrespective of participants’ intrinsic navigation skills, being connected with a program or social worker whose role was to arrange appropriate resources was a universally protective factor.

Self-advocacy is operationalized as an individual's proactivity in speaking up for themselves when they feel they need something more than what was currently offered to them. Participants demonstrated self-advocacy in a variety of ways: some approached their physicians and pharmacists to ask for generic medications, others found pharmacies with the lowest dispensing fees, and yet others found subsidy relief programs for various services by demanding them: I just had to do things on my own … you have to be willing to fight, you have to be willing to really push for what you want … you just learn to fight for yourself and just be strong. If you don’t have the ability to do it nobody's gonna do it for you. Several participants with higher levels of education stated that it was their education that enabled their self-advocacy ability. They expressed sentiments of compassion and empathy toward others with similar ailments and barriers but without their degree of education and competency.

3.4. Predisposing factors

3.4.1. Perceived injustice and discrimination

Individuals who had been financially stable before their financial barrier arising were especially prone to faring poorly. They were people who were not accustomed to experiencing tight financial circumstances: Emotionally I think it's very hard to go from a very independent single mom to all of a sudden have to worry about pennies. These people often described having undergone a very difficult identity transition or transformation. They were often particularly susceptible to feelings of shame and embarrassment.

Several participants voiced feeling sentiments of injustice or persecution. The injustice was either general (i.e., directed toward god, the universe, etc.) or directed toward institutions (e.g., social service agencies, insurance companies, and social assistance programs) or individuals (e.g., healthcare providers, the wealthy, and family members). These sentiments were often based on significant negative experiences with these institutions or individuals.

Most participants described having had experienced some form of discrimination in their lives—from healthcare providers, service providers, police, or the general public. They identified that this happened based on their illness/disability or because of their lack of financial means: …and then people look at you, some people that have money “look at you, oh, you’re just a welfare bum.” The dominant impression for many participants who felt persecuted or experienced discrimination was to develop feelings of inadequacy and inferiority which was not conducive to resiliency: You feel like almost like you’re second class cause you don’t have the money to do anything so if you don’t have the money then you gotta be poor and so poor means you’re second class.

3.4.2. Comorbidities

A variety of comorbid conditions acted to exacerbate and magnify the impact of financial barriers on participants’ lives. These included physical disabilities, mental illness, and chronic pain. Those who had physical disabilities and chronic pain described feeling stuck in their financial situation because their health limited their ability to work to improve their situation. This compounding effect of physical disability and financial barriers was particularly predominant among the cohort of participants who had suffered from strokes.[20]

Participants who suffered from depression and/or anxiety disorders were especially susceptible to the impact of financial barriers. Some individuals identified that this experience exacerbated their mental health struggles through the inability to afford pursing their interests and social activities: Well, it's depressing, I have nothing to look forward to … I guess I’ll be working the rest of the year just to make sure I can stay on top of these drugs. Others described having financial barriers to accessing mental healthcare services (e.g., counseling), which may be important for some participants to deal with the distress associated with chronic illnesses.

Another frequently identified comorbid situation was having had a personal history of traumatic experiences or difficult prior circumstances, which hindered participants’ mental and emotional ability to deal with additional challenges (such as financial barriers) in a resilient manner. These experiences included physical and sexual abuse, unexpected deaths of loved ones, bankruptcy and financial mismanagement, criminal activity and prosecution, and addictions.

3.5. Modifying factors

Situated between protective and predisposing factors in our framework are the filters labeled modifying factors. These are factors which by their very nature are dichotomous and have the potential to be either protective or predisposing.

3.5.1. Healthcare provider interaction

Healthcare providers had the potential to make a substantial impact on how participants perceived their financial barrier. There were many stories of physicians and pharmacists who assisted their patients with financial difficulties by connecting them with social workers and other resources. By contrast, we heard poignant stories of physicians who were exceptionally insensitive about their patients’ financial circumstances: They don’t understand the fact of well gee, mister, we need you to do this, we need you to do that. Yeah, okay, but they don’t take this all [the cost] into consideration. We report further detailed examples of how healthcare providers influence the impact of financial barriers in a separate publication.[21]

Healthcare providers can be protective agents against the impact of financial barriers simply by asking patients about the presence of these as part of their routine clinical practice. We heard that often patients felt that some providers were more interested in their ability to afford treatments than others. One participant in particular implied that their specialist physicians simply did not seem to have much interest in the reality of their financial barriers: My family doctor's very well aware of it, so is the pharmacy, they’re great, in fact they’re really, really great. And my specialists, they don’t need to know, you only see them, you know ….

3.5.2. Coping mechanisms

Participants utilized a variety of coping strategies to deal with stressful financial circumstances. The psychology literature often refers to healthy strategies as “adaptive” and negative coping as “maladaptive.” One of the primary distinctions is that adaptive coping is “problem focused,” while maladaptive coping tends to be “emotion focused.”[22] There were very clear examples of both types of strategies employed by our respondents. Adaptive, problem-focused coping strategies were plentiful among those who displayed determination/resiliency, such as So the less money you make, you adjust …. I mean sure it took a while to get used to but we’re getting by now. By contrast, emotion-focused coping strategies were predominant among the less resilient: Nowadays I can’t do nothing. It's kind of frustrating … sometimes I’m still crying …. Like I’m frustrated or devastated and I just flare out.

3.5.3. Individual responsibilities

Many participants described having a variety of personal, family, and professional obligations. Some described these as factors contributing to the stress of their financial barrier, while others felt that having external responsibilities helped them to cope with their barrier. For example, a participant described how he needed to be strong because he had several children to support both financially and emotionally. His strength was a source of comfort to his family through their very difficult times.

Conversely, a participant who was an immigrant to Canada had suffered a debilitating stroke, she could no longer afford to provide resources to her extended family in her home country. In this instance, she experienced guilt and stress about no longer being able to provide for them, and these responsibilities were deleterious: I supposed to help them but I am not …. I said to my husband, “how can I help them when I can’t even help myself?.” They’re the ones to have to help me.

3.5.4. Social support/isolation

A variety of social influences on participants were modifying factors. Those who had strong social support networks were protected from negative impacts of their financial barriers. Social support could come from family, friends, or even fellow patients and could come in the form of emotional support: What do I have to live for, really? I know I have my daughter which keeps me going, or financial assistance: We’ve always managed. We sacrifice, all my kids work and they throw in money for me too. We’re a big loving family. Another important role of social support was that with more people helping out, healthcare system navigation abilities were enhanced. For example, an elderly participant's son was able to purchase a used treadmill online which enabled her to remain physically active.

By contrast, social isolation plays an important role in the impact of having a financial barrier. Participants who felt some degree of isolation before experiencing their financial barrier were particularly negatively impacted. Many participants’ primary social interactions involved some degree of spending (e.g., dining out and going for coffee) and they described having to substantially cut back on these activities as a result of their financial barrier, which often worsened feelings of isolation and despair: I don’t go out to dinner …. I don’t go to shows, I don’t go to concerts. I don’t have much of a social life. I have some friends, but I don’t do a lotta things in terms of going out places. For some, this had significant consequences on their lives: I’m really becoming a shut in now I think … a lot of it is because I can’t afford to do anything.

3.6. Lens

The aggregate of the various filters an individual possesses (protective, predisposing, and modifying factors) often foreshadowed how impactful a financial barrier would be for any given participant. However, these filters were then viewed through the lens of an individual's attitude or worldview. For example, we heard stories of participants whose combination of filters were strongly predisposing—whom one might presume would experience significant impacts from their financial barrier—but who were able to rise above these challenges and keep the impact of their financial barrier to a minimum due largely to a positive worldview: I try to stay positive and … you know what, that's a great life. So I take my little treasures, my little trinkets and put it in my pocket and that carries me. Some of those with more positive worldviews described being shaped by religion or faith: I’ve never been without, the Lord has always provided and my faith is huge, while for others leaned on a belief in karma or fate: I’ve been pretty lucky. In the 11th hour things turn around and things happen and it gets better, so something will happen.

By contrast, there were other participants whose worldview was one of negativity and denial, which had the potential to overturn even the most positive set of protective factors. For example, a participant with postsecondary education, no comorbidities or traumatic life experiences, and a reasonable income stated categorically Well I don’t foresee this getting any better.

The “lens” is an important element of the framework as it emphasizes that while a participant's underlying circumstances have a strong direct effect on the impact of financial barriers, these are not necessarily deterministic—some participants with financial barriers and overall very difficult situations and backgrounds were able to achieve resiliency, at least partly due to positivity or faith.

3.7. Resiliency

Research team members and participants agreed that resiliency was the overarching theme that ran through virtually all experiences, even if participants did not name it as such. Some of the terms used to describe the notion of resilience included perseverance, a constant battle, managing, and getting by.

We conceptualized that the combination of filters and the lens projected each participant's experience somewhere on a spectrum of resiliency, ranging from determination to despair. Participants who demonstrated determination were exceptionally resilient and had the capacity to thrive in the face of significant financial barriers. These were individuals who continued to strive for positive mental and physical health despite the challenges in their path: Well, I think I’m just the type of person that doesn’t let things, I mean I’ve had a tough life my whole life, but if I let everything bother me I’d be in a looney bin. [Laughter] So you can’t, but I know there's a lot of people that get stressed out with everything.

Conversely, participants with a predominance of predisposing factors and a negative worldview often seemed to default to despair when the stress of their financial barrier and health concerns overwhelmed their ability to cope:

You know, you try and do all these things for your health and all that does is cost, cost, cost. So then you think “ahh ok I’ll just stay fat, keep smoking, maybe I should take up drinking too.” I’m frustrated because I’m trying so hard to get healthy, and it's just costing so much.

There was a remarkable consistency in the idea of this experience being an ongoing struggle. This was described using a number of phrases, some described going in circles, chasing my tail, a chicken and egg thing, and catch 22. However, the most commonly cited metaphor for this sentiment was that of a vicious cycle—represented graphically in the framework nested within the resiliency spectrum. The use of this graphic was validated through member checking, as participants strongly related to the idea that even if they were near the top of the resiliency spectrum, there is always a constant downward force that they had to battle daily. Several also voiced that once one starts down the spiral, it is a steep descent to despair and very difficult to climb back out.

3.8. Clinical outcomes

While not the focus of this paper, several respondents described experiencing adverse clinical outcomes such as worsened disease control, emergency department visits, inpatient admissions, or cardiovascular events. These adverse events were almost always described as being preceded by at least 1 of several deleterious behaviors including poor health behaviors, discontinuation of regular self-monitoring, missing appointments with healthcare providers, and/or becoming nonadherent to preventive medications.

Anecdotally, adverse events seem to be associated with a participant's resiliency level. This is to say that a participant with a relatively minor barrier who had a predominance of predisposing factors and a negative worldview seemed to have less resiliency and be more prone to adverse events. However, even those with more significant barriers could overcome them through use of protective factors and a positive worldview, thereby approaching their barrier with greater determination and resiliency, minimizing the likelihood of adverse events.

4. Conclusion

Using grounded theory methodology, we developed a novel framework to specifically understand the experience that patients with cardiovascular-related chronic disease may have in the face of financial barriers. We found that a variety of factors, called filters, influenced how impactful a financial barrier could be on any given patient, and when interpreted through an individual's worldview, their degree of resiliency was revealed. Although prior studies have suggested an association between experiencing financial barriers and adverse clinical outcomes,[7,11] the nature of this association has been uncertain. Our study suggests that the link between these 2 phenomena is likely more complex than was previously envisioned. The potential of financial barriers to affect future adverse events may be closely linked to an individual patient's degree of resiliency, which results from their unique set of filters and their lens or worldview.

Coming from primarily clinical backgrounds, we anticipated hearing from patients how their financial barriers resulted in adverse medical outcomes. Given that a perception of financial barriers was requisite for study eligibility, we had assumed that financial barriers would have similar effects on all participants. This was not in fact the case, with the significant heterogeneity in the impact of financial barriers providing some of our richest findings.

This is a relatively small study (though adequate for qualitative work of this nature[23]), thus we cannot claim that this proposed framework will be representative of every individual who experiences a financial barrier. However, true to the principles of qualitative research, the objective of the study was to obtain a deep and thorough understanding of this phenomenon rather than striving for representativeness. The transferability of our study may be questioned given that we only included patients with cardiovascular-related chronic conditions. However, this framework could be applicable to other chronic conditions, such as respiratory or gastrointestinal diseases (e.g., emphysema or inflammatory bowel disease), for example. There are likely some conditions, such as mental illness, that may be experienced in substantially different ways than the more physical conditions we have described. It is also important to note that financial barriers are likely not exclusively reserved for those who have chronic diseases, as individuals who have limited financial resources may face financial barriers to accessing episodic care they may require—our framework is likely not transferable to this population.

Finally, the transferability of the framework may be questioned on the basis that it was developed from a cohort of Canadian participants. It is true that the nature of financial barriers may differ from one country to another (e.g., Western European nations with comprehensive health insurance vs the United States with a predominance of private insurance and large numbers of uninsured individuals). However, we feel that Canada is somewhat of a middle ground, with public coverage for physician and hospital services but primarily private coverage for medications. Furthermore, Medicare coverage for Americans over the age of 65 years is similar to the programs offered in Alberta. Furthermore, under the affordable care act, nonsenior Americans are compelled to purchase or obtain private health insurance with significant premiums and copayments that may pose financial barriers.[8] While the exact services to which barriers are experienced may differ, the process experienced by individual patients is likely similar across countries, so our framework is likely transferable to settings beyond Canada.

Our framework can be used as the basis for future research on the topic of financial barriers. Investigators interested in the impact of financial barriers now have a dedicated conceptual framework, which is grounded in data, upon which to base their research questions and approaches. One particularly rich area for future research would be trying to quantify the associations among financial barriers, aspects of resiliency, and clinical outcomes. Furthermore, we feel that our framework is instructive for clinicians who are likely to encounter patients who experience financial barriers. Clinicians should consider the various factors which contribute to their patients’ likely future success in self-managing their chronic illness in the face of financial barriers and how they might contribute to bolstering protective factors while minimizing those that might predispose patients to the negative effects of their financial barriers.

This novel framework may also serve as a template for future health policy in the area of improving access to healthcare services. Our framework demonstrates that in healthcare systems where the complete elimination of financial barriers is not possible or not feasible, other strategies may be employed to minimize the effects of these barriers, including enhanced provider education, improved patient navigation, and adequate subsidy/support programs.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge our research participants and thank them for the time that they devoted to their participation in this study, as well as their openness and honesty. We would like to thank Ms Jo Anne Plested for her support with participant enrollment, scheduling, interviews, and data analysis; and Ms Sarah Gil for her assistance with the design of Fig. 1. We are grateful for the assistance with recruitment that we received from Drs Julie McKeen, Jim Stone, Sandeep Aggarwal, Michael Hill, and Sean Dukelow.

These data have been presented at the Canadian Association of Health Services and Policy Research Annual Meeting (Toronto, May 2016) and the Alberta Strategy for Patient Oriented Research Summer Institute (Calgary, May 2016).

Footnotes

Abbreviations: None.

Funding/support: The study was funded by Alberta Innovates—Health Solutions through a Collaborative Research and Innovation Opportunities grant (Interdisciplinary Chronic Disease Collaboration) and a clinician fellowship training award (DJTC).

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose over the past 3 years.

References

- [1].Watkins LO. Epidemiology and burden of cardiovascular disease. Clin Cardiol 2004;27:III2–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Hobbs FD. Prevention of cardiovascular diseases. BMC Med 2015;13:261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Thompson PD, Buchner D, Pina IL, et al. Exercise and physical activity in the prevention and treatment of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: a statement from the Council on Clinical Cardiology (Subcommittee on Exercise, Rehabilitation, and Prevention) and the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism (Subcommittee on Physical Activity). Circulation 2003;107:3109–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Ronksley PE, Sanmartin C, Campbell DJ, et al. Perceived barriers to primary care among western Canadians with chronic conditions. Health Rep 2014;25:3–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Frohlich KL, Ross N, Richmond C. Health disparities in Canada today: some evidence and a theoretical framework. Health Policy 2006;79:132–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Smith GD, Hart C, Watt G, et al. Individual social class, area-based deprivation, cardiovascular disease risk factors, and mortality: the Renfrew and Paisley Study. J Epidemiol Community Health 1998;52:399–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Campbell DJ, King-Shier K, Hemmelgarn BR, et al. Self-reported financial barriers to care among patients with cardiovascular-related chronic conditions. Health Rep 2014;25:3–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Campbell DJ, Soril L, Clement F. The impact of cost-sharing mechanisms on patient-borne medication costs. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176:1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Demers V, Melo M, Jackevicius C, et al. Comparison of provincial prescription drug plans and the impact on patients’ annual drug expenditures. CMAJ 2008;178:405–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Law MR, Cheng L, Dhalla IA, et al. The effect of cost on adherence to prescription medications in Canada. CMAJ 2012;184:297–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Rahimi AR, Spertus JA, Reid KJ, et al. Financial barriers to health care and outcomes after acute myocardial infarction. JAMA 2007;297:1063–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Campbell DJ, Manns B, Hemmelgarn BR, et al. The Development of a Conceptual Framework for Understanding Financial Barriers to Care for Patients with Cardiovascular-Related Chronic Disease: a protocol for a grounded theory (qualitative) study. CMAJ Open 2016;4:e304–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Rosenstock IM. The health belief model and preventive health behavior. Health Educ Behav 1974;2:354–86. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Aday LA, Andersen R. A framework for the study of access to medical care. Health Serv Res 1974;9:208–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Brown AF, Ettner SL, Piette J, et al. Socioeconomic position and health among persons with diabetes mellitus: a conceptual framework and review of the literature. Epidemiol Rev 2004;26:63–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Grossman M. The demand for health after a decade. J Health Econ 1982;1:1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Charmaz K. Constructing Grounded Theory. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Glaser B. The constant comparative method of qualitative analysis. Soc Probl 1965;12:436–45. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Strauss AL, Corbin JM. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Ganesh A, King-Shier K, Manns B, et al. Money is brain: financial barriers and consequences for Canadian stroke patients. Can J Neurol Sci. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Campbell DJ, Manns B, Hemmelgarn B, et al. Financial barriers to care and diabetes: an exploratory qualitative study. Diabetes Educ. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Zeidner M, Saklofske D. Zeidner M, Endler N. Adaptive and maladptive coping. John Wiley & Sons, Handbook of Coping: Theory, Research, Applications. New York, NY:1996. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Sandelowski M. Sample size in qualitative research. Res Nurs Health 1995;18:179–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]