Abstract

Factors driving healthcare transformation include fragmentation, access problems, unsustainable costs, suboptimal outcomes, and disparities. Cost and quality concerns along with changing social and disease-type demographics created the greatest urgency for the need for change. Caring for and paying for medical treatments for patients suffering from chronic health conditions are a significant concern. The Affordable Care Act includes programs now led by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services aiming to improve quality and control cost. Greater coordination of care—across providers and across settings—will improve quality care, improve outcomes, and reduce spending, especially attributed to unnecessary hospitalization, unnecessary emergency department utilization, repeated diagnostic testing, repeated medical histories, multiple prescriptions, and adverse drug interactions. As a nation, we have taken incremental steps toward achieving better quality and lower costs for decades. Nurses are positioned to contribute to and lead the transformative changes that are occurring in healthcare by being a fully contributing member of the interprofessional team as we shift from episodic, provider-based, fee-for-service care to team-based, patient-centered care across the continuum that provides seamless, affordable, and quality care. These shifts require a new or an enhanced set of knowledge, skills, and attitudes around wellness and population care with a renewed focus on patient-centered care, care coordination, data analytics, and quality improvement.

There are transformative changes occurring in healthcare for which nurses, because of their role, their education, and the respect they have earned, are well positioned to contribute to and lead. To be a major player in shaping these changes, nurses must understand the factors driving the change, the mandates for practice change, and the competencies (knowledge, skills, and attitudes) that will be needed for personal and systemwide success. This article discusses the driving factors leading to healthcare transformation and the role of the registered nurse (RN) in leading and being a fully contributing member of the interprofessional team as we shift from episodic, provider-based, fee-for-service care to team-based, patient-centered care across the continuum that provides seamless, affordable, and quality care. This new health paradigm requires the nurse to be a full partner in relentless efforts to achieve the triple aim of an improved patient experience of care (including quality and satisfaction), improved outcomes or health of populations, and a reduction in the per capita cost of healthcare.

Driving Forces for Change: Cost and Quality Concerns

Table 1 provides an overview of key factors that have been driving healthcare reform. Unsustainable growth in healthcare costs without accompanying excellence in quality and health outcomes for the U.S. population has been escalating to the point at which federal and state budgets, employers, and patients are unwilling or unable to afford the bill (Harris, 2014). The United States spends more on healthcare than any other nation. In fact, it spends approximately 2.5 times more than the average of other high-income countries. Per capita health spending in the United States was 42% higher than Norway, the next highest per capita spender. In 2014, U.S. health care reached $3.0 trillion, or $9,523 per person (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [CMS], 2014). This is almost 20% of the gross domestic product (GDP), meaning that for every $5 spent in the federal budget, about $1 will go to healthcare. The largest expenditures are for hospital care (about 32%), physician and clinical services (26%), and prescription drugs (10%) (CMS, 2015). With the demographic shifts in the aging population and those with chronic illness, it is anticipated that in three short years, healthcare spending will reach $4.3 trillion (George & Shocksnider, 2014, p. 79; Hudson, Comer, & Whichello, 2014, p. 201).

Table 1. Drivers of Change.

| Cost |

|

| Waste |

|

| Variability and lack of standardization |

|

| Quality |

|

| Healthcare system infrastructure |

|

| Mistargeted incentives—Reimbursement |

|

| Aging demographics and increased longevity |

|

| Chronic illness |

|

| Healthcare disparities |

|

Note. GDP = gross domestic product.

The high cost of care is, in part, driven by the greater use of sophisticated medical technology, greater consumption of prescription drugs, and higher healthcare prices charged for these procedures and medications (The Commonwealth Fund, 2015). Also contributing to high cost is waste. It is estimated that 30 cents of every dollar spent on medical care in United States is wasted, amounting to $750 billion annually. Components of waste include inefficient delivery of care, excessive administrative costs, unnecessary services, inflated prices, prevention failures, and fraud (Berwick & HackBerth, 2012; Mercola, 2016).

Not only are the prices for procedures significantly higher in the United States but also the charges for similar procedures vary dramatically, even within the same geographic locale. Reporting on the variability in healthcare charges for similar procedures, The Washington Post (Kliff & Keating, 2013) conveyed the federal government's release of the prices that hospitals charge for the 100 most common inpatient procedures (CMS, 2013). The numbers revealed large, seemingly random variation in the costs of services. For joint replacements, the most common inpatient surgery for Medicare patients, prices ranged from a low of $5,304 in Ada, OK, to $223,373 in Monterey Park, CA. The average charge across the 427,207 Medicare patients' joint replacements was $52,063. Looking at cost variation in a smaller geographic area, the Blue Cross Blue Shield (2015) study of cost variations for knee and hip replacement surgical procedures in the United States found similar cost variability. In the Dallas market, a knee replacement could cost between $16,772 and $61,585 (267% cost variation) depending on the hospital (Blue Cross Blue Shield, 2015).

Perhaps, if this outrageous price tag bought value, we as a nation would accept the expense. After all, healthcare is more vital than most other goods or services. However, the stark reality is that despite outspending all other comparable high-income nations, our system ranks last or near last on measures of health, quality, access, and cost. The United States has higher infant mortality rates, higher mortality rates for deaths amenable to healthcare (mortality that results from medical conditions for which there are recognized healthcare interventions that would be expected to prevent death), higher lower extremity amputations due to diabetes, higher rates of medical, medication, and laboratory errors, and higher disease burden, as measured by “disability-adjusted life-years,” than comparable countries (Peterson-Kaiser Health Tracker System, 2015).

Examining quality within the system, we know that our healthcare system is fragmented with recurring communication failure and unacceptable levels of error. The system is difficult to navigate, especially when patients and caregivers are asked to seek care across multiple providers and settings for which there is little to no coordination. There are significant barriers to accessing care, and this problem is disproportionately true for racial and ethnic minorities and those with low-socioeconomic status (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [AHRQ], 2011). With a focus almost exclusively on acute care, the primary care system in the United States is in disarray or, for some, nonexistent despite research data that associate access to primary care with lower mortality rates and lower overall healthcare costs (Bates, 2010). It is not surprising therefore that when discharged from the hospital, an average of one in five Medicare patients (20%) was readmitted to the hospital within 30 days after discharge in 2009 and 34% were readmitted within 90 days. Moreover, 25% of Medicare patients discharged to long-term care facilities were readmitted to the hospital within 30 days, clearly representing gaps in care coordination (Enderlin et al., 2013, p. 48).

The absence or underuse of peer accountability, underdeveloped quality improvement infrastructures, lack of accountability for making quality happen, inconsistent use of guidelines and provider decision-support tools, and lack of clinical information systems that have the capacity to collect and use digital data to improve care all contribute to quality care issues (Shih et al., 2008). Another impediment to quality is the hierarchical structure of most healthcare organizations that “inhibits communication, stifles full participation, and undermines teamwork” (Leape, 2014, p. 1570). Failure of these organizations to adopt and enforce “no tolerance” policies for behaviors that are known to impact quality (i.e., disrespectful, noncollaborative care among team members that impedes safety to ask questions and express ideas; failure to comply with basic care approaches such as hand washing hygiene and time-out protocols that are known to decrease safety risk) perpetuates the dysfunctional culture in healthcare where negative behaviors block progress toward quality (Leape, 2014).

Driving Factors for Change: Changing Demographics

Changing social and disease-type demographics of our citizens is also fueling the mandate for change. The demographer James Johnson coined the phenomenon “the browning of America” to illustrate that people of color now account for most of the population growth in this country. People of color face enduring and long-standing disparities in health status including access to health coverage that contributes to poorer health access and outcomes and unnecessary cost. The AHRQ in its annual National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report has provided evidence that racial and ethnic minorities and poor people face more barriers to care and receive poorer quality of care when accessed. These facts underscore the imperative for change in our system.

The graying of America is another changing social demographic, with significant healthcare implications. Beginning January 1, 2011, the oldest members of the Baby Boom generation turned 65. In fact, each day since that day, today, and for every day for the next 19 years, 10,000 Baby Boomers will reach the age of 65 years (Pew Research Center, 2010). Currently, just 14.1% of the U.S. population (44.7 million) is older than 65 years. By 2060, this figure will be 98 million or about twice their current number (Administration on Aging, n.d.). This shift will have significant economic consequences on Social Security and Medicare.

Overlapping with the changing social demographics is the change in disease-type demographics due to the fact that there is a rise in chronic disease among Americans and significantly so among older Americans. Chronic disease (heart disease, stroke, cancer, Type 2 diabetes, obesity, and arthritis) is the leading cause of death and disability for our citizens, affecting an estimated 133 million people. Thought of by some as the single biggest force threatening U.S. workforce productivity, as well as healthcare affordability and quality of life, chronic diseases are among the most “common, costly, and preventable of all health problems” (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], n.d.-b). Those with chronic conditions utilize the greater number of healthcare resources, accounting for 81% of hospital admissions, 91% of prescriptions filled, 76% of all physician visits, and more than 75% of home visits (Partnership to Fight Chronic Disease, n.d.). Not surprisingly, older people are more likely to have more comorbidities. Eighty-five percent of adults aged 65 years have at least one chronic disease, 62% have two or more chronic diseases, and 23% have five or more chronic conditions, and these 23% account for two thirds of all Medicare spending (Volland, 2014).

The situation becomes even more serious when the person also has a disability or activity limitation. Our episodic healthcare model is not meeting the needs of people with chronic conditions and often leads to poor outcomes (Anderson, 2010). More than a quarter of people with chronic conditions have limitations when it comes to activities of daily living such as dressing and bathing or are restricted in their ability to work or attend school. The number of people with arthritis is expected to increase to 67 million by 2030 and of these 25 million will have arthritis-attributable activity limitations (CDC, n.d.-a). These numbers are conservative, as they do not incorporate the current obesity trends that are likely to add to future cases of osteoarthritis. A significant challenge, both now and for the future, is how to care for and pay for the care—medical treatment and other supportive services—that people with chronic conditions need.

Voluntary Change Is Not Enough

As a nation, we have taken incremental steps toward achieving better quality and lower costs for decades. With the turn of the century and the Institute of Medicine (IOM) reports, To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health Care System and Crossing the Quality Chasm, we became increasingly aware that the level of unintended harm in medicine was too high and that there was a compelling need to scrupulously examine and transform systems to make healthcare safer and more reliable. The recommendations in Crossing the Quality Chasm (IOM, 2001) called for adopting a shared vision of six specific aims for improvement that must be the core for healthcare (see Table 2). Although, in principle, there was agreement that these six aims were critical for an improved and effective system and should be evident across all settings, the reality is that widespread change did not occur. As suggested in the report, there was an immense divide between what we knew should be provided and what actually was provided. This divide was not a gap but a chasm, and it was believed that the healthcare system as it existed was fundamentally unable to achieve real improvement without a major system overhaul.

Table 2. Six Aims for Improvement from Crossing the Quality Chasm.

| 1. Safe. Safety must be a system property of healthcare where patients are protected from injury by the system of care that is intended to help them. Reducing risk and ensuring safety require a systems focus to prevent and mitigate error. |

| 2. Effective. Care and decision making must be evidence based with neither underuse nor overuse of the best available techniques. |

| 3. Patient-centered. Care must be respectful and responsive of individual patient's culture, social context, and specific needs, ensuring that patients receive the necessary information and opportunity to participate in decisions and have their values guide all clinical decision making about their own care. |

| 4. Timely. The system must reduce waits and harmful delays. |

| 5. Efficient. The system must avoid waste, including waste of equipment, supplies, ideas, time, and energy. |

| 6. Equitable. Care must be provided equitably without variation in quality because of personal characteristics such as race, gender, ethnicity, geographic location, and socioeconomic status. |

Enter Healthcare Reform

Continued skyrocketing of healthcare costs, less than impressive heath status of the American people, safety and quality issues within the healthcare system, growing concerns that cost and quality issues would intensify with changing demographics, and the reality that there were 50 million Americans uninsured and 40 million underinsured in the United States ushered in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (Salmond, 2015). The Affordable Care Act (ACA) is more than insurance reform and greater access for the newly insured but includes programs now led by the CMS aiming to improve quality and control costs—what is being termed value. Value is in essence a ratio, with quality and outcomes in the numerator and cost in the denominator (Wehrwein, 2015).

Improving value means “avoiding costly mistakes and readmissions, keeping patients healthy, rewarding quality instead of quantity, and creating the health information technology infrastructure that enables new payment and delivery models to work” (Burwell, 2015). Through the ACA and the power vested in the CMS to implement value, we are shifting to new principles underlying reimbursement and new models for care and payment (see Table 3). For a while, healthcare, like a seesaw, will balance in a precarious state of transition from the old to the new (Cipriano, 2014); however, no one is expecting a return to the old approaches of payment and care. In fact, it is expected by 2018 that 50 cents of every Medicare dollar will be linked to an identified quality outcome or value (Burwell, 2015). And as the nation's largest insurer, Medicare leads the way in steering new programs and setting the precedent for other private insurers.

Table 3. New Approaches, Programs, and Models Supported by the ACA.

| The new principles for payment | |

| Pay for Performance (P4P) | P4P is the basic principle that undergirds new models of care being supported by the ACA. In these models, providers are rewarded for achieving preestablished quality metrics. The quality metrics for acute care organizations targets the experience of care (HCAHPS), processes of care (such as processes to reduce healthcare-associated infections and improve surgical care), efficiency, and outcomes (i.e., rates of mortality, surgical site infections). In the ambulatory care area, quality performance may be determined by any of the HEDIS measures. The key point for practitioners is total familiarity with how quality is being defined and measured. Knowing this allows for full participation in what must be done to achieve the quality. |

| Value-Based Purchasing (VBP) | This approach switches the traditional model of healthcare fee structure from fee-for-service where reimbursement is for the number of visits, procedures, and tests to payment based on the value of care delivered—care that is safe, timely, efficient, effective, equitable, and patient-centered. In VBP, insurers such as Medicare set annual value expectations and accompanying incentive payment percentages for each Medicare patient discharge. The purchasers of healthcare are able to make decisions that consider access, price, quality, efficiency, and alignment of incentives and can take their business to organizations/providers with established records for both cost and quality (Aroh, Colella, Douglas, & Eddings, 2015). |

| Shared Savings Arrangements | Approaches to incentivize providers to offer quality services while reducing costs for a defined patient population by reimbursing a percentage of any net savings realized. Medicare has established shared savings programs in the PCMH and ACO models of care. |

| New programs and models of delivery and payment | |

| Hospital-Acquired Condition Reduction Program | Under the ACA, Medicare payments for hospitals that rank in the lowest performing quartile for conditions that are hospital-acquired (i.e., infections [central line-associated bloodstream infections and catheter-associated urinary tract infections], postoperative hip fracture rate, postoperative sepsis rate, postoperative pulmonary embolism, or deep vein thrombosis rate) will be reduced by 1%. Upcoming standards will be expanded to include methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections (CMS, n.d.). |

| Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program | Aimed at reducing readmissions within 30 days of discharge (readmission that currently cost Medicare $26 billion per year). To reduce admissions, hospitals must have better coordination of care and support. Hospitals with relatively high rates of readmissions will receive a reduction in Medicare payments. These penalties were first applied in 2013 to patients with congestive heart failure, pneumonia, and acute myocardial infarction. The CMS added elective hip and knee replacements at the end of 2014 (Purvis, Carter, & Morin, 2015). |

| In time, 60-, 90-, and 190-day readmissions will be examined. | |

| Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) | The ACO is a network of health organizations and providers that take collective accountability for the cost and quality of care for a specified population of patients over time. Incentivized by shared savings arrangements, there is a greater emphasis on care coordination and safety across the continuum, avoiding duplication and waste, and promoting use of preventive services to maximize wellness. |

| Better coordinated, preventive care is anticipated to save Medicare dollars, and the savings will be shared with the ACO. It is estimated that ACOs will save Medicare up to $940 million in the first 4 years (Sebelius, 2013). | |

| Patient-Centered Medical Homes (PCMHs) | PCMHs is an approach to delivery of higher quality, cost-effective, primary care deemed critically important for people living with chronic health conditions. Medical homes share common elements including comprehensive care addressing most of the physical and mental health needs of clients through a team-based approach to care; patient-centered care providing holistic care that builds capacity for self-management through patient and caregiver engagement that attends to the context of their culture, unique needs, preferences, and values; coordinated care across the continuum of healthcare systems including specialty care, hospitals, home healthcare, and community services and supports. Such coordination is particularly critical during transitions between sites of care, such as when patients are being discharged from the hospital; accessible care that minimizes wait times and includes expanded hours and after-hours access; and care that emphasizes quality and safety through clinical decision-support tools, evidence-based care, shared decision making, performance measurement, and population health management and incorporation of chronic care models for management of chronic disease (AHRQ, PCMH Resource Center). The CMS has supported demonstration projects to shift its clinics to the medical home model. |

| Bundled Payment Models | Bundles are single payment models targeting discrete medical or surgical care episodes such as spine surgery or joint replacement. Bundles provide lump sum to providers for a given service episode of care inclusive of preservice time, the procedure itself, and a postservice global period, thereby crossing both inpatient and outpatient services. Can be for a procedure or an episode of care ... providers assume a considerable portion of the economic risk of treatment (McIntyre, 2013). The margin (positive or negative) realized in this process depends on the ability of the different organizations and providers to manage the costs and outcomes across the care continuum. |

| The Medicare Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement model is a bundled care package aimed to support better and more efficient care for those seeking hip and knee replacement surgical procedures. The bundle covers the episode from the time of the surgery through 90 days after hospital discharge. | |

| Private insurers and businesses are offering bundled payment packages for their participants to receive specialized joint or spine care at approved high-quality, cost-effective facilities. For example, Lowe's and Walmart arrange for no-cost knee and hip replacement surgical procedures for their 1.5 million employees and their dependents if they seek care at one of four approved sites in the United States. These companies will cover the cost of consultations and treatment without deductibles along with travel, lodging, and living expenses for the patient and the caregiver (The Advisory Company, 2013). | |

Note. ACA = Affordable Care Act; ACO = Accountable Care Organizations; CMS = Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; PCMH = Patient-Centered Medical Home.

As illustrated in Table 4, these new models are shifting the paradigm of care from a disease model of treating episodic illness, without attention to quality outcomes, to a focus on health and systems that reward providers for quality outcomes and intervening to prevent illness and disease progression—in keeping populations well. Quality will be defined in terms of measurable outcomes and patient experience at the individual and population levels, and payments (penalties and incentives) will be calculated on the basis of the outcomes. Efficiency will be maximized by reducing waste, avoiding duplicative care, and appropriately using specialists. Outcomes will be tracked over longer periods of time—making care integration and care across the continuum a mandate. Institutions and providers will be incentivized for keeping people well so as not to need acute hospital or emergency department (ED) service, for meeting care and prevention criteria, and for ensuring the perceived value of the healthcare experience or patient satisfaction is high. This forces a shift from a provider-centric healthcare system where the provider knows best to a delivery system that is patient-centric and respectfully engages the patient in developing self-management and behavioral change capacity. Funds have been made available through the ACA via the CMS to help providers invest in electronic medical records and other analytics needed to track outcomes and to provide support in developing the skills and tools needed to improve care delivery and transition to alternative payment models (McIntyre, 2013).

Table 4. Shifting Paradigms From the Past to the Future.

| The Past | The Future |

|---|---|

| Payment for illness or sick care that is triggered by visits to providers and procedures done | Payment for prevention, care coordination, and care management at the primary care level |

| Greatest financial award for specialized services | Payment for populations—shared risk for use of specialized services |

| Provider-centric, provider as expert | Patient-centric, patient as partner |

| No accountability for inadequate quality. Quality and quality improvement tasked to a department | Value-based payment asking “How well did patients do?” Quality and quality improvement prime concerns of every practitioner |

| Quality measured at the individual level | Quality measured at the individual and aggregate levels |

| Quality measured for a discrete time period | Quality measured over longer periods |

| Inconsistent access to care | Same-day appointments, timely access |

| Disrespect | Respect |

| Top-down hierarchical command and control. Leadership focused on siloed area of care | Team-based, collaborative care requiring integration of care across the continuum |

| Nursing not leading or not recognized for their contribution to care | Nursing finding their voice and take an active role in shaping the future of healthcare. Nursing recognized for their value in care coordination |

| Following orders | Advocating for the patient and the family |

| Focus on task | Focus on excellence and the patient experience |

We have been experiencing the first wave of changes toward value-based care for years. In 2002 (and updated in 2006), the National Quality Forum (NQF) developed a list of seriously reportable events in healthcare (such as surgery on the wrong body part or a mismatched blood transfusion) that became known as “never events.” These never events were considered to be serious and costly healthcare errors that should never happen and are largely preventable through safety procedures and/or the use of evidence-based guidelines. Quality improvement measures were instituted to reduce “never events” to zero. It required establishing a culture of safety such that incidents could be safely reported and performing root–cause analyses when “never” events occurred (Lembitz & Clarke, 2009).

In October 2008, the CMS began denying payment for hospitals' extra costs to treat complications that resulted from certain hospital-acquired conditions (HACs). Some of the conditions from these two lists shared similarities (surgery on the wrong patient or wrong body part, death/disability from incompatible blood, Stage 3 or 4 pressure ulcers after admission, and death/disability associated with a fall within the facility). These events represent rare, serious conditions that should not occur. However, other conditions included on Medicare's “no pay” list of HACs were selected because they were high cost or high volume (or both) and assumed preventable through use of evidence-based guidelines. Some of these HACs occur more commonly and have a comparatively greater impact on cost. These “no pay” adverse events identified by the CMS but not by the NQF included deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism in total knee and hip replacement and surgical site infection following orthopaedic surgery. This CMS policy was directed to accelerate improvement of patient safety by implementation of standardized protocols to prevent the event. These newly defined “never events” limit the ability of the hospitals to bill Medicare for adverse events and complications (Lembitz & Clarke, 2009). Emerging from quality improvement initiatives to prevent “never events” was the concept of “always events” or behavior that should be consistently implemented to maximize patient safety and improve outcomes. Examples of “always events” include “patient identification by more than one source, mandatory “read backs” of verbal orders for high-alert medications, surgical time-out and making critical information available at handoffs or transitions in care” (Lembitz & Clarke, 2009, p. 31).

Today, we have the Hospital Acquired Condition Reduction Program, implemented prior to the ACA but formalized under this Act to broaden its definition of unacceptable conditions. It uses financial penalties for high quartile scores in rates of adverse HACs. These conditions, considered to be reasonably preventable conditions that were not present upon admission to the hospital (see Table 3), must be monitored and reported. Lowering these rates has occurred with careful monitoring and surveillance for events, implementation of evidence-based best practices, creating checklists to ensure processes are followed, and transferring patients out of EDs and critical care units as soon as possible.

Bundled payments, a model reimbursing two or more providers for a discrete episode of care over a specific period of time, are being used in orthopaedics for some spine and total hip and knee arthroplasty surgical procedures. A fully bundled payment system extends beyond the institution, as it includes the surgeons and all other providers involved in the care of the patient during and after surgery. In this bundled model, lump sum payments are given to the institution to cover the episode of care from the preservice or presurgery period, through the procedure itself, and to a postservice period, generally anywhere from 30 to 90 days after surgery. This eliminates fee-for-service where one payment is made to the hospital, a second payment to the surgeon, and other payments to the anesthetist, the physical therapist, homecare, etc. The bundled payment is a prenegotiated type of risk contract in which providers will not be compensated for any costs that exceed the bundled payment. In addition to breaking down the current payment silos, bundles set quality standards to further the IOM aims of healthcare that eliminates duplication and waste, increases efficiency, uses evidence-based protocols to maximize outcomes, and engages the patient in building capacity for self-care (Enquist et al., 2011; McIntyre, 2013).

The Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement model is a bundled approach targeting higher quality and more efficient care for Medicare's most common inpatient surgical procedures—hip and knee replacements. Institutions under this model have reengineered patient care processes and standards developing standardized clinical pathways to enhance reliability or consistency in care. Processes identified as important include comprehensive patient teaching spanning from the preadmission phase to the postdischarge recovery phase, standardized order sets, early mobilization, redesign of services for colocation for patient rather than provider ease, use of nurse practitioners to champion the pathway and ensure compliance, and implementing efforts to move patients from the hospital to home with home healthcare as opposed to hospital to inpatient rehabilitation to home with home healthcare (Enquist et al., 2011; Marcus-Aiyeku, DeBari, & Salmond, 2015). Practicing in a bundled model requires that organizations examine the distribution of costs across the service or episode, identify, understand, and eliminate variation, map evidence-based pathways of care, coordinate care with providers across the continuum, and use ongoing evaluation and analytics to identify where care can be managed more efficiently and effectively (American Hospital Association, n.d.).

Moving forward, we will see greater attention to addressing preventive and chronic care needs across an entire population. The emphasis will be on interventions that prevent acute illness and delay disease progression and will require a true interprofessional team model to accomplish. Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) and Patient-Centered Medical Homes are expected to improve primary care and care across the continuum by incentivizing providers to be accountable for improving patient and population health outcomes through cost-sharing approaches to reimbursement. It is more than the traditional health visit and will require a focus on both the individual and the population to advance health. Primary healthcare under the ACA stresses prevention, health promotion, continuous comprehensive care, team approaches, collaboration, and community participation (Gottlieb, 2009, p. 243).

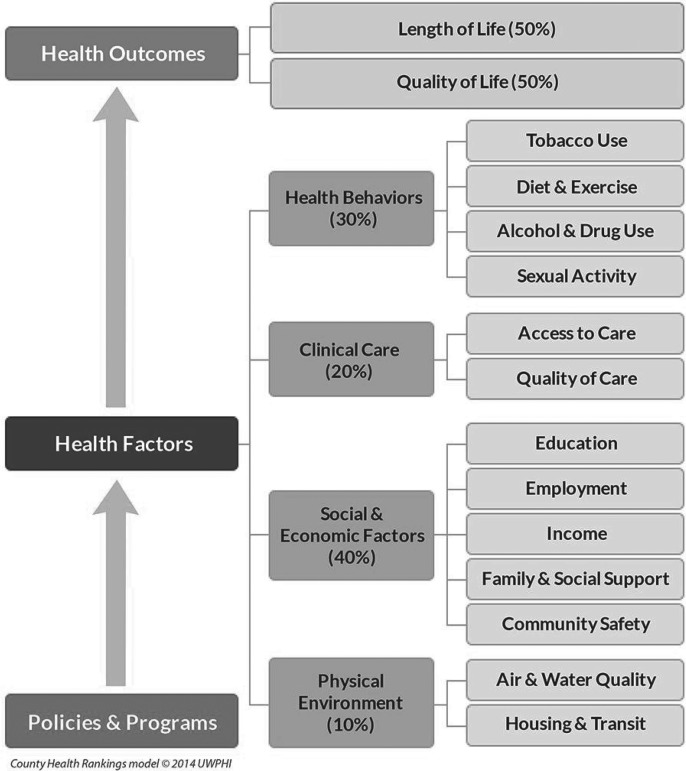

If ACOs are to achieve their goals to improve the health of populations and realize a positive profit margin, they will need to adopt new ways of thinking about health. There is growing awareness that overall health outcomes are influenced by an array of factors beyond clinical care. Figure 1 illustrates the County Health Rankings model of population health. As can be seen, health outcomes defined as length and quality of life are determined by factors in the physical environment, social and economic factors, clinical care, and health behaviors. The model recognizes that “health is as much the product of the social and physical environments people occupy as it is of their biology and behavior” (Kaplan, Spittel, & David, 2015, p. iv). Using this framework, it is easy to recognize the critical need to incorporate behavioral factors and social context when trying to improve well-being and health outcomes. Individual behavioral determinants include addressing issues related to diet, physical activity, alcohol, cigarette, and other drug use, and sexual activity, all of which contribute to the rates of chronic disease. The social and physical contexts (together comprising what is called social determinants of health) of where a person lives and works influence half of the variability in overall health outcomes, yet rarely are considered when one thinks of healthcare. Table 5 presents social and physical determinants as defined by Healthy People 2020. If we are to achieve true population health, it will be essential to have models in which clinical care is joined with a broad array of services supporting behavioral change and is integrated or coordinated with other community and public health efforts to address the social context in which people live and work. With these new reimbursement models, healthcare organizations and providers will be incentivized to identify the other 80% of factors (health behaviors, social and economic factors, and physical environment factors) and address them to improve patient outcomes and generate savings.

Figure 1.

County Health Rankings, Model of Population Health. From University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute. County Health Rankings & Roadmaps 2016. www.countyhealthrankings.org. Used with permission.

Table 5. Social and Physical Determinants of Health as Defined by Healthy People 2020.

| Social Determinants | Physical Determinants |

|---|---|

| Availability of resources to meet daily needs (e.g., safe housing and local food markets) Access to educational, economic, and job opportunities Access to health care services Quality of education and job training Availability of community-based resources in support of community living and opportunities for recreational and leisure-time activities Transportation options Public safety Social support Social norms and attitudes (e.g., discrimination, racism, and distrust of government) Exposure to crime, violence, and social disorder (e.g., presence of trash and lack of cooperation in a community) Socioeconomic conditions (e.g., concentrated poverty and the stressful conditions that accompany it) Residential segregation Language/literacy Access to mass media and emerging technologies (e.g., cell phones, the Internet, and social media) Culture |

Natural environment, such as green space (e.g., trees and grass) or weather (e.g., climate change) Built environment, such as buildings, sidewalks, bike lanes, and roads Worksites, schools, and recreational settings Housing and community design Exposure to toxic substances and other physical hazards Physical barriers, especially for people with disabilities Aesthetic elements (e.g., good lighting, trees, and benches) |

Nursing's Role in the New Healthcare Arena

The Future of Nursing: Leading Change, Advancing Health asserts that nursing has a critical contribution in healthcare reform and the demands for a safe, quality, patient-centered, accessible, and affordable healthcare system (IOM, 2010). To deliver these outcomes, nurses, from the chief nursing officer to the staff nurse, must understand how nursing practice must be dramatically different to deliver the expected level of quality care and proactively and passionately become involved in the change. These changes will require a new or enhanced skill set on wellness and population care, with a renewed focus on patient-centered care, care coordination, data analytics, and quality improvement.

Transformation and the changes required will not be easy—at the individual or systems level. Individually, it requires an examination of one's own knowledge, skills, and attitudes and whether that places you as ready to contribute or resist the coming change. At an organizational level, it requires an analysis of mission, goals, partnerships, processes, leadership, and other essential elements of the organization and then overhauling them, thus disrupting things as we know it. The reality is that everyone's role is changing—the patients', physicians', nurses', and other healthcare professionals'—across the entire continuum of care. Success will come if all healthcare professionals work together to transform and leverage the contribution of each provider working at full scope of practice. Achieving patient-centered, coordinated care requires interprofessional collaboration, and it is an opportunity for nursing to shine.

Focusing on Wellness

We must shift from a care system that focuses on illness to one that prioritizes wellness and prevention. This means that wellness- and preventive-focused evaluations, wellness and health education programs, and programs to address environmental or social triggers of preventable disease conditions and care problems must take an equal importance of focus as the disease-focused clinical intervention that providers deliver (Volland, 2014). What does this look like in the real-world orthopaedic setting? At a population health level, this means addressing “upstream” factors to prevent or minimize musculoskeletal health problems. For example, workplace programs to assess and prevent back and other musculoskeletal diseases and disabilities or fall-reduction programs held in the community to improve mobility for seniors both address specific populations with an aim of keeping the group well and preventing musculoskeletal injury. Upstream of joint surgery could entail intervening prior to surgery with programs around weight loss and exercise that could prevent many chronic musculoskeletal disorders and ultimately avoid or delay surgery and improve outcomes in the case that surgery is needed.

At the organizational and individual practitioner levels, wellness means thinking about the patient beyond the current event (hospital or office) and considering what must be assessed or done to maximize the person's wellness. For example, a 60-year-old woman presents to the ED for a fall. She identified that she had been having some leg edema and could not wear her normal shoes so was walking in a slipper-type shoe and slipped. The acute episode is treated by obtaining an x-ray film to rule out fracture and a cardiac review to determine cause for edema. A wellness perspective would go further and consider what are the possible risks for future falls—a gait analysis would be done, screening for osteoporosis would be arranged for, and a plan to prevent or reduce risk to prevent subsequent falls and potential fractures would be implemented with possible referral to a Matter of Balance program that could support the patient with strategies to reduce falling and increase strength and balance.

The key is that instead of simply asking “What is wrong here” or “What is wrong now” and focusing on the immediate episode that brought the person to the clinic or the hospital, the nurse also asks, “What happened that the person needed this level of care?” “What could or should have been done to better manage the person's health or prevent this episode? “What needs to be done to prevent a recurrence or a worsening of presenting issue?”

Knowing the answer to these questions allows for the development of a more individualized, holistic plan of care that can begin at the moment and subsequently be coordinated and managed across the continuum by RNs and other providers no matter the care continuum setting.

Whether looking to stay well or recover from acute illness or live well with chronic illness, there are few community-based programs that meet one's rehabilitation and wellness needs. Nursing and other healthcare professionals such as therapists and social workers are well positioned to lead entrepreneurial ventures that partner with community centers (YMCAs, adult day care, housing, etc.) or participate in shared medical appointments to provide education, skills development, and activities that maximize health and support continuing residence and care in the community.

Patient- and Family-Centered Care

Another necessary characteristic of the transformed healthcare system must be an unwavering focus on the patient. Patient- and family-centered care, rather than provider-centric care, is essential if patients and families are to assume responsibility for self-management. The IOM (2001) defines patient-centered care as:

Health care that establishes a partnership among practitioners, patients, and their families (when appropriate) to ensure that decisions respect patients' wants, needs, and preferences and that patients have the education and support they need to make decisions and participate in their own care. (p. 7)

Again, nurses are ideally positioned for this role, as nursing has consistently embraced an approach to care that is holistic, inclusive of patients, families, and communities and oriented toward empowering patients in their care to assume responsibility for self- and disease management (American Nurses Association [ANA], 2012; George & Shocksnider, 2014; Samuels & Woodward, 2015).

Practicing from a patient-centered approach means acknowledging that patients, not providers, know themselves best and realizing that quality care can only be achieved when we integrate patients and families into decision making and care and focus on what is important to patients. Without this, we will never deliver value. Gone are the days of telling the patient what to do; rather, asking “what matters to you” must begin the care process. It helps define patient-reported outcomes or outcomes of medical care that are defined by the patient directly. This shared understanding of what matters to the patient provides the entrée for discussion of how to efficiently achieve these outcomes. Engaging the patient in shared decision making and shared care planning with patient-reported outcomes at the center of the plan of care is essential for patient activation in self-management. With patient-reported outcomes in mind, nurses can partner with patients in providing client education and coaching to strengthen the patient's capacity toward goal achievement. Use of motivational interviewing and action planning as a strategy to assist patients with behavioral change is a needed skill. With action plans and goals at the forefront, the nurse provides ongoing information on treatment plans, provides coaching and counseling to build self-confidence in relation to new behaviors, coordinates reminders for preventive and follow-up care, and ensures that handoffs provide the next set of providers with needed information to continue the plan of care and avoid duplicative ordering.

Care Coordination

An integrated care continuum is posited to be a key strategy for achieving the triple aim—better quality, better service, and lower costs per unit of service. But what is the continuum and what is the role of the nurse in care coordination across the continuum? The continuum of care concept was proposed in 1984 and was conceptualized as a patient-centered system that guides and follows individuals over time (potentially from birth to end of life) through a comprehensive array of seamless health, mental health, and social services spanning all levels and intensity of care (Evashwick, 1984). The World Health Organization (2008, p. 4) similarly defines an integrated service delivery as “the management and delivery of health services so that clients receive a continuum of preventive and curative services, according to their needs over time and across different levels of the health system.” Today, these definitions hold, although there is a greater emphasis on the need to expand the continuum to collaborate within the community to engage support of agencies and services provided by other nonprofits (George & Shocksnider, 2014). As the continuum consists of services from wellness to illness, from birth to death, and from a variety of organizations, providers, and services, ongoing coordination to prevent or minimize fragmentation is critical.

Lamb (2014) emphasizes that the “work of care coordination occurs at the intersection of patients, providers, and healthcare settings and relies on integrative activities including communication and mobilization of appropriate people and resources” (p. 3). All patients need care coordination as it serves as a bridge—making the fragmented health system become coherent and manageable—an asset for both the patient and the provider. For some patients, a more intensive form of care coordination is needed and may be assigned a care manager to oversee their condition and changing care needs during the different trajectories of their chronic illness. Others may require a time-limited set of care and coordination services to ensure care continuity across different sites or levels of care. This care, referred to as transitional care, has been a major focus, as it has been validated that transitions represent high-risk periods for safety issues and negative outcomes because of lack of continuity of care (Enderlin et al., 2013). During this shifting in setting, provider, or status, there have typically been problems with handoffs such that the next provider/setting does not have the information about what has been done for the patient, the patient and family lack understanding and ability to manage the care, medications have not been reconciled, and patients have been challenged in getting access to the care needed. To contend with these issues, the ACA set goals to reduce fragmentation of care. Numerous transitional care models such as Naylor's Transitional Care Model, Coleman's Care Transitions Program, and Project Re-engineered Discharge have demonstrated efficacy in reducing readmissions, reducing visits to the ED, improving safety, and improving patient satisfaction and outcomes (ANA, 2012; Enderlin et al., 2013).

Whatever the level of care coordination required, the care coordinator uses skills of patient advocacy to promote self-management, navigate complex systems, and ensure meaningful patient- and family-centered communication and interprofessional communication to facilitate a seamless, efficient plan of care that spans the boundaries within and between the patient/family and formal organizational and community service providers (Fraher, Spetz, & Nayor, 2015). Care coordination is not something that is delegated to one individual or unique to an individual who may hold the title of care coordinator or navigator. All nurses, no matter what their role, must prioritize care coordination. With this in mind, all nurses should move away from the notion of discharging patients, which implies that their responsibilities for care are finished. In contrast, nurses should provide care with a mind to transitioning the patient to the next level or stage. Transitioning implies a joint responsibility for care coordination over time. To know what transition needs are, the nurse must understand the patient's condition in respect to his or her own life continuum and context and work to handoff to the next provider/site of care. It is often the nurse at the point of care who has formed a relationship with the patient and learned important aspects of the patient's social context, challenges in managing the patient's health, and the patient's priorities of care. This information is invaluable and must be integrated into the plan of care for the patient across the continuum of care.

For those with more complex care needs, especially those with multiple chronic illnesses, there is a need for a specialized role to ensure that care is coordinated across the continuum. Care coordinator roles grounded in acute care or primary and ambulatory (case or care managers, population health managers, patient navigators, healthcare coaches, transition coaches) may be held by individuals with different professional and nonprofessional roles. Nurses, with their unique skill set and philosophy of care, are the provider of choice to lead, manage, and participate in the care coordination of groups of patients (ANA, 2012; George & Shocksnider, 2014; Rodts, 2015). Nurses have both the clinical and management knowledge and skill set needed to assume key coordination roles. Strong clinical knowledge grounded in the evidence is a priority characteristic for the care coordinator as this individual must be able to select and implement care processes and systems reflecting best practices, implement rapid-cycle improvements in response to clinical data, and track and analyze trends. Lack of this requisite clinical knowledge will impede implementation of best practices and potentially impede strong interprofessional collaboration and communication that must be exquisite within a well-coordinated delivery system. Nurses have this unique clinical knowledge, making them ideal for navigating care across the continuum.

The American Academy of Ambulatory Care Nursing has identified nine key competencies for care coordination and transition management to include support for self-management, education and engagement of patients and families, cross-setting communications and care transitions, coaching and counseling of patients and families, nursing process (a proxy for monitoring and evaluation), teamwork and collaboration, patient-centered care planning, population health management, and advocacy (Haas, Swan, & Haynes, 2013). The Medical-Surgical Nursing Certification Board and the American Academy of Ambulatory Care Nursing have collaborated to provide a certification in Care Coordination and Transition Management. Information is available at https://www.msncb.org/cctm.

Data Analytics: A Focus on Outcomes and Improvement

We can only improve the care and health of populations if we truly understand the care we deliver. Understanding the care requires data. Nurses in the transformed healthcare system will need to be able to gather data and track clinical and financial data over time and across settings. Tracking of key metrics (treatments, health status, functionality, quality of life) must occur at the individual and population levels. This gives needed information to understand the particular issues the individual patient is facing. However, “if you only look at an individual's health, you can miss important trends across a group of patients within a population or community” (Appold, 2016, p. 1). Improving care at the individual level requires consideration of information on the population from which the individual is drawn.

The first step in understanding populations is to have a much deeper understanding of the patient population in order to drive better outcomes. Practice-based population health is defined as an approach to care that uses information on a group (“population”) of patients within a care setting or across care settings (“practice-based”) to improve the care and clinical outcomes of patients (Cusack, Knudson, Kronstadt, Singer, & Brown, 2010). To achieve the triple aim, it will be essential that we track outcomes over time related to psychosocial status, behavior change, clinical and health status, satisfaction, quality of life, productivity, and cost. These data are used in predictive modeling to stratify the population according to disease state or risk profile. This information can then be used to engage patients in timely, proactive, tailored manner based on their needs. Using stratification, those at no or low risk will be recipients of health promotion and wellness and care. Those at moderate risk will require more intensive interventions, ranging from health risk management to care coordination and advocacy. Those who are at high risk and are high utilizers require further disease or case management services (Care Continuum Alliance, 2012; Verhaegh et al., 2014). These data are used at the individual level to align the type of care with the patient need and at the organizational level to focus resources on segments of the population at greatest need.

Outcome data are one piece of the information needed for improvement. With outcomes in mind, one needs to examine what can be done to improve outcomes related to the experience, efficiency, or effectiveness of care. Use of shadowing as a technique to examine the real-time care experience provides valuable data on process flow, patient experience, and team communication. Seeing care through the eyes of the patient allows for an assessment of the current state and development of improved processes that are grounded in information provided by patients and families (DiGioia & Greenhouse, 2011; Marcus-Aiyeku et al., 2015). Combining shadowing data with Lean Six Sigma methodology or with rapid-cycle improvement processes is an approach for ongoing quality improvement that must be integrated into role expectations of the professional care team.

This is not an independent effort. In today's practice environment, interprofessional learning collaboratives targeting specific populations (i.e., joint replacement, elder hip fracture) are forming within and across organizations. These collaborative groups as organized through quality departments, local hospital associations, the Institute of Health Innovation, and professional medical and nursing associations use benchmark data, shared either from their own facilities or from registries (i.e., the American Joint Replacement Registry) to examine variations in patient outcomes. This is complemented by discussions and sharing around best practices and system approaches to improvement that can be implemented in rapid improvement cycles at the point of care where the interprofessional team collaborates on an identified problem, process issue, or care gap, looking together for what is best for the patient.

Moving Forward

There is no doubt that nurses are poised to assume roles to advance health, improve care, and increase value. However, it will require new ways of thinking and practicing. Shifting your practice from a focus on the disease episode of care to promoting health and care across the continuum is essential. Truly partnering with patients and their families to understand their social context and engage them in care strategies to meet patient-defined outcomes is essential. Gaining greater awareness of resources across the continuum and within the community is needed so that patients can be connected with the care and support needed for maximal wellness. Tracking outcomes as a measure of effectiveness and leading and participating in ongoing improvement to ensure excellence will require exquisite teamwork as excellence crosses departments, roles, and responsibilities. “Nurses can no longer take a back seat—the time has come for nursing, at the heart of patient care, to take the lead in the revolution to making healthcare more patient-centered and quality-driven” (Salmond, 2015, p. 282). The question you must ask is “Are you ready?”

For 28 additional continuing nursing education activities on health care reform, go to nursingcenter.com/ce.

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- Administration on Aging. (n.d.). Aging statistics. Retrieved from http://www.aoa.acl.gov/aging_statistics/index.aspx

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). (2011). Access to healthcare. In National Healthcare Quality Report, 2011 (Chap. 9). Retrieved from http://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/nhqrdr/nhqr11/chap9.html

- Allen J., Ottmann G., Roberts G. (2013). Multi-professional communication for older people in transitional care: a review of the literature. International Journal of Older People Nursing, 8(4), 253–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Hospital Association. (n.d.). Moving towards bundled payment. Retrieved from http://www.aha.org/content/13/13jan-bundlingissbrief.pdf

- American Nurses Association (ANA). (2012). The value of nursing care coordination: A white paper of the American Nurses Association. Retrieved from http://www.nursingworld.org/carecoordinationwhitepaper

- American Public Health Association. (2012). The Prevention and Public Health Fund: A critical investment in our nation's physical and fiscal health. Available at: https://www.apha.org/∼/media/files/pdf/factsheets/apha_prevfundbrief_june2012.ashx

- Anderson G. (2010). Chronic care: Making the case for ongoing care. Retrieved from http://www.rwjf.org/content/dam/farm/reports/reports/2010/rwjf54583

- Appold K. (2016). Why hospitalists should embrace population health. The Hospitalist. Retrieved from http://www.the-hospitalist.org/article/why-hospitalists-should-embrace-population-health

- Aroh D., Colella J., Douglas C. (2015). An example of translating value-based purchasing into value-based care. Urologic Nursing 35(2), 61–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates D. W. (2010). Primary care and the U.S. health care system: What needs to change? Journal of General Internal Medicine, 25(10), 998–999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berwick D., HackBerth A. (2012). Eliminating waste in U.S. healthcare. JAMA, 307(14), 1513–1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blue Cross Blue Shield. (2015). A study of cost variations for knee and hip replacement surgeries in the U.S. Retrieved from http://www.bcbs.com/healthofamerica/BCBS_BHI_Report-Jan-_21_Final.pdf

- Burwell S. M. (2015). Setting value-based payment goals—HHS efforts to improve US health care. N Engl J Med 372(10), 897–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Care Continuum Alliance. (2012). A population health guide for primary care models. Washington, DC: Author; Retrieved from http://www.exerciseismedicine.org/assets/page_documents/PHM%20Guide%20for%20Primary%20Care%20HL.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.-a). Chronic diseases: The leading causes of death and disability in the United States. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/overview/

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.-b). Future arthritis burden. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/arthritis/data_statistics/national-statistics.html

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (n.d.). Better care, smarter spending, healthier people improving our health care delivery system. Retrieved from https://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Fact-sheets/2015-Fact-sheets-items/2015-01-26.html

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2013). Medicare provider utilization and payment data. Retrieved from https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/Medicare-Provider-Charge-Data/index.html

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2014). National Health Expenditures 2014 highlights. Retrieved from https://www.cms.gov/research-statistics-data-and-systems/statistics-trends-and-reports/nationalhealthexpenddata/downloads/highlights.pdf

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Office of the Actuary, National Health Statistics Group. (2015). National Health Expenditures Projections 2014–2024. Spending growth faster than recent trends. Health Affairs, 34(8), 1407–1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cipriano P. (2014). Reaching the end game: Total population health. American Nurse Today, 9(6). [Google Scholar]

- Cusack C. M., Knudson A. D., Kronstadt J. L., Singer R. F., Brown A. L. (2010). Practice-based population health: Information technology to support transformation to proactive primary care (Prepared for the AHRQ National Resource Center for Health Information Technology under Contract No. 290-04-0016, AHRQ Publication No. 10-0092-EF). Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. [Google Scholar]

- DiGioia A., III, Greenhouse P. K. (2011). Patient and family shadowing: Creating urgency for change. Journal of Nursing Administration, 41(1), 23–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enderlin C. A., McLeskey N., Rooker J. L., Steinhauser C., D'Avolio D., Gusewelle R., Ennen K. A. (2013). Review of current conceptual models and frameworks to guide transitions of care in older adults. Geriatric Nursing, 34, 47–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enquist M., Bosco J. A., Pazand L., Habibi K. A., Donoghue R. J., Zuckerman J. D. (2011). Managing episodes of care: Strategies for orthopedic surgeons in the era of reform. Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery, 93, e55, 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evashwick C. J. (1984, August 14). Caring for the elderly: Building and financing a long-term care continuum. Annual meeting of the American Hospital Association, Denver, CO. [Google Scholar]

- Fraher E., Spetz J., Nayor M. (2015, June). Nursing in a transformed health care system: New roles, new rules. Princeton, NJ: Interdisciplinary Nursing Quality Research Initiative, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; Retrieved from www.inqri.org [Google Scholar]

- George V. M., Schocksnider J. (2014). Leaders: Are you ready for change? The clinical nurse as care coordinator in the new health care system. Nursing Administration Quarterly, 38(1), 78–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb L. M. (2009). Learning from Alma Ata: The medial home and comprehensive primary healthcare. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 22, 242–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas S., Swan B. A., Haynes T. (2013). Developing ambulatory care registered nurse competencies for care coordination and transition management. Nursing Economic$, 31(1), 44–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris M. B. (2014). Massachusetts Health care reform and orthopaedic trauma: Lessons learned. Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma, 28(10, Suppl.), S20–S22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson R., Comer L., Whichello R. (2014). Transitions in a wicked environment. Journal of Nursing Management, 22(2), 201–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. (2001). Envisioning the National Health Care Quality Report. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. (2010). The future of nursing: Leading change, advancing health. Retrieved from http://books.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=12956&page=R1

- Kaplan R., Spittel M., David D. (Eds.). (2015). Population health: Behavioral and social science insights (AHRQ Publication No. 15-0002). Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research, National Institutes of Health. [Google Scholar]

- Kliff S., Keating D. (2013, May 13). One hospital charges $8,000—Another, $38,000. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2013/05/08/one-hospital-charges-8000-another-38000/?utm_term=.df77d3feb313

- Lamb G. (2014). Care coordination: the game changer. Silver Spring, MD: American Nurses Association. [Google Scholar]

- Leape L. (2014). Patient safety in the era of healthcare reform. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 473, 1568–1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lembitz A., Clarke T. J. (2009). Clarifying “never events” and introducing “always events.” Journal of Patient Safety in Surgery, 3, 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lytton M. Prevention in practice: December 30, 2013. Taking stock of health in 2013. American Journal of Preventive Medicine: Prevention in Practice. Available at: https://ajpmonline.wordpress.com/page/2/

- Marcus-Aiyeku U., DeBari M., Salmond S. (2015). Assessment of the patient-centered and family-centered care experience of total joint replacement patients using a shadowing technique. Orthopaedic Nursing, 34(5), 269–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre L. F. (2013). Exploring new practice models delivering orthopedic care: Can we significantly decrease delivery costs and improve quality. Sports Medicine and Arthroscopy Review, 21(3), 152–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercola J. (2016). US health care system wastes more money than the entire Pentagon budget annually. Health Impact News. Retrieved from http://healthimpactnews.com/2013/us-health-care-system-wastes-more-money-than-the-entire-pentagon-budget-annually

- Orszag P. R., Ellis P. (2007). Addressing rising health care costs—a view from the Congressional Budget Office. New England Journal of Medicine 357(19), 1885–1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partnership to Fight Chronic Disease. (n.d.). The growing crisis of chronic disease in the United States. Retrieved from http://www.fightchronicdisease.org/sites/default/files/docs/GrowingCrisisofChronicDiseaseintheUSfactsheet_81009.pdf

- Peterson-Kaiser Health Tracker System. (2015). Health of the healthcare system: An overview. Retrieved from http://www.healthsystemtracker.org/chart-collection/health-of-the-healthcare-system-an-overview

- Pew Research Center. (2010). Baby boomers retire. Retrieved from http://www.pewresearch.org/daily-number/baby-boomers-retire

- Purvis L., Carter E., Morin P. (October 30, 2015). Hospital readmission rates falling among older adults receiving joint replacements. AARP Public Policy Institute. Available at: http://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/ppi/2015/hospital-readmission-rates-falling-among-older-adults-receiving-joint-replacements.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Rodts M. (2015). What's in the name? Care management ... More important than ever. Orthopaedic Nursing, 34(1), 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmond S. (2015). Nurses leading change: The time is now! In Forrester D. A. (Ed.), Nursing's greatest leaders: A history of activism (Chap. 12). New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Samuels J. G., Woodward R. S. (2015). Opportunities to improve pain management outcomes in total knee replacements: patient-centered care across the continuum. Orthopaedic Nursing 34(1), 4–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebelius J. (January 10, 2012). More doctors, hospitals partner to coordinate care for people with Medicare. Available at: https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2013/01/10/more-doctors-hospitals-partner-to-coordinate-care-for-people-with-medicare.html

- Shih A., Davis K., Schoenbaum S. C., Gauthier A., Nuzum R., McCarthy D. (2008). Organizing the U.S. health care delivery system for high performance. New York, NY: The Commonwealth Fund; Retrieved from http://www.commonwealthfund.org/∼/media/files/publications/fund-report/2008/aug/organizing-the-u-s-health-care-delivery-system-for-high-performance/shih_organizingushltcaredeliverysys_1155-pdf.pdf [Google Scholar]

- The Advisory Committee. (2013). Walmart, Lowe's enter bundled pay deal with four health systems. The Daily Briefing, October 9, 2013. Available at: https://www.advisory.com/Daily-Briefing/2013/10/09/Walmart-Lowes-enter-bundled-pay-deal-with-four-health-systems.

- The Commonwealth Fund. (2015). U.S. Healthcare from a global perspective. The Commonwealth Fund Issues Brief. Retrieved from http://www.commonwealthfund.org/∼/media/files/publications/issue-brief/2015/oct/1819_squires_us_hlt_care_global_perspective_oecd_intl_brief_v3.pdf

- Verhaegh K. J., MacNeil J. L., Eslami S., Geerlings S. E., de Rooij S. E., Burman B. M. (2014). Transitional care interventions prevent hospital readmissions for adults with chronic illnesses. Health Affairs, 33(9), 1531–1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volland J. (2014). Creating a new healthcare landscape. Nursing Management, 45(4), 22–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waidmann T. (2009). Estimating the cost of racial and ethnic health disparities. The Urban Institute. Available at: http://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/alfresco/publication-pdfs/411962-Estimating-the-Cost-of-Racial-and-Ethnic-Health-Disparities.PDF

- Wehrwein P. (2015, August). Value = (Quality + Outcomes)/Cost. Managed Care. Retrieved from http://www.managedcaremag.com/archives/2015/8/value-quality-outcomes-cost [Google Scholar]

- Wertenberger S., Yerardi R, Drake A. C., Parlier R. (2006). Veterans Health Administration Office of Nursing Services exploration of positive patient care synergies fueled by consumer demand: care coordination, advanced clinic access, and patient self-management. Nursing Administration Quarterly, 30(2), 137–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2008). Integrated health services—What and why? (Technical Brief No. 1). Retrieved from http://www.who.int/healthsystems/service_delivery_techbrief1.pdf